1. Introduction

Remote sensing change detection (RSCD), as a vital topic in remote sensing information extraction, has been widely applied in various fields such as urban expansion monitoring [

1], land use/cover change analysis [

2], and disaster assessment [

3]. In recent years, deep learning (DL) methods have emerged as the mainstream approach for RSCD due to their powerful feature extraction capabilities, end-to-end training mechanisms, and excellent nonlinear modeling abilities [

4].

Based on the network architecture of DL methods, RSCD methods can generally be categorized into Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based methods and Transformer-based methods [

5]. CNN-based methods have constructed a series of representative network architectures by introducing multi-layer convolutional structures for feature extraction and difference analysis. Early representative works achieved end-to-end pixel-level change detection by building dual-path encoder structures and incorporating cross-layer skip connections [

6], which to some extent enhanced the perception of change regions. Additionally, to overcome the difficulty of insufficient recognition capability when detecting subtle or fine changes, subsequent models based on multi-scale feature fusion structures have been successively proposed [

7,

8]. Recently, some scholars also pay attention to feature interaction capabilities and efficiency considerations [

9,

10,

11]. Despite achieving some results, CNN-based methods still rely primarily on local receptive fields—struggling to model long-range dependencies and global change patterns, and failing to effectively address inadequate accurate modeling for large-scale or non-local changes in complex scenarios.

To overcome the deficiency of CNNs in global modeling, the Transformer architecture, based on the self-attention mechanism, has emerged [

12]. It not only excels in global modeling but also demonstrates superior performance in capturing long-range dependencies, handling complex backgrounds, and adapting to multi-scale changes—thus becoming another mainstream direction in RSCD [

13]. For example, the Bitemporal Image Transformer (BIT) model captures cross-temporal spatio-temporal dependencies in a compact token representation, significantly enhancing the perception of large-scale change patterns [

14]. ChangeFormer with a hierarchical Transformer encoder structure, combines multi-stage difference modeling with a lightweight decoding strategy, thus enhancing the representation ability for different scale changes [

15].

Whether CNN-based or Transformer-based methods, ensuring model accuracy often relies on large-scale training samples [

16]. However, RSCD tasks generally face annotated sample scarcity [

17], which hinders existing models from effectively learning and extracting key features from limited data—restricting training effectiveness and causing obvious deficiencies in feature perception and complex-scenario performance [

18]. Vision foundation models, pre-trained on massive datasets, possess strong feature extraction and cross-task transfer capabilities. They provide a solution for sample-scarce scenarios: even in remote sensing tasks with insufficient training samples, these models can still maintain stable performance [

19]. Among them, the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [

20] is a typical representative, having been widely applied in remote sensing tasks such as object detection and building segmentation with promising results. Leveraging its excellent semantic understanding capability, recent studies have begun exploring its application in RSCD.

To alleviate domain differences between natural images and remote sensing images, researchers have widely adopted adapter-based transfer strategies for both binary change detection and semantic change detection tasks [

21]. For example, Ding et al. [

22] uses convolutional adapters to aggregate task-relevant change information for binary change detection, and introduces a semantic branch to model potential semantic representations in bitemporal remote sensing images. Mei et al. [

23] adapts SAM through a context-aware dual encoder and a progressive feature aggregation dual decoder architecture—providing a targeted solution for the more refined semantic-level change extraction task. These studies indicate that SAM’s semantic information exhibits good adaptability and enhancement effects in change detection tasks. Specifically, Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technology, by introducing a small number of trainable parameters into pre-trained models for efficient fine-tuning, offers a superior solution for precise adaptation of SAM in the remote sensing domain [

24].

In total, existing SAM-based change detection methods mostly adopt adapter strategies for fine-tuning [

25]. While these methods can alleviate the weak feature extraction capability caused by insufficient annotated data, they generally overlook a core challenge: how to effectively separate true change information from bitemporal features. Models usually struggle to accurately distinguish interference from complex backgrounds, resulting in prominent missed detections and false alarms. From the essence of the change detection task, its core objective is to accurately extract change information from bitemporal images. Analyzing this problem from a frequency domain perspective reveals distinct frequency characteristics of change detection: (1) change information typically manifests as mid-to-high frequency signals relative to the background; (2) non-change information, by contrast, is mainly concentrated in the low-frequency band. Therefore, constructing a mechanism that can effectively separate and selectively enhance high- and low-frequency components—while combining it with SAM’s deep semantic representation capability to improve the model’s ability to discriminate true changes—has become a key path to overcoming the limitations of existing methods.

Fourier transform inherently enables mapping image signals to the frequency domain and performing precise decomposition and modulation in the frequency dimension [

26,

27], making it an ideal tool for explicit separation of change information and suppression of interference. Compared with traditional spatial domain methods, frequency domain transformation not only possesses global modeling capabilities but, more importantly, can selectively enhance mid-to-high frequency components related to changes (based on frequency characteristics) while effectively suppressing low-frequency interference. Based on this theoretical foundation, fusing Fourier transform with the SAM foundation model can achieve accurate extraction and enhancement of change information through a frequency-domain feature separation mechanism—while preserving SAM’s powerful semantic understanding capability.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, this paper proposes a SAM fine-tuning adaptation RSCD based on Fourier frequency domain analysis difference reinforcement (SAM-FDN). In this method, we utilize the feature extraction capability of the SAM and adopt a low-rank fine-tuning strategy to construct the feature extraction backbone network. Then, we use Fourier frequency domain analysis to construct a Fourier Change Feature Extraction-Separation Module (FCEM). This module employs the Fourier transform to separate high-frequency variation information from low-frequency invariant information, thereby improving the accuracy of RSCD. In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) We propose a novel framework, SAM-FDN, that couples the SAM with a frequency domain-aware mechanism through a low-rank fine-tuning strategy, enabling more effective change detection in complex scenarios with limited labeled data.

(2) We design a plug-and-play FCEM that introduces a learnable complex weight matrix. This module performs adaptive modulation in the frequency domain to precisely separate and enhance change-related high-frequency information while suppressing low-frequency background noise.

2. Method

2.1. Overall Architecture

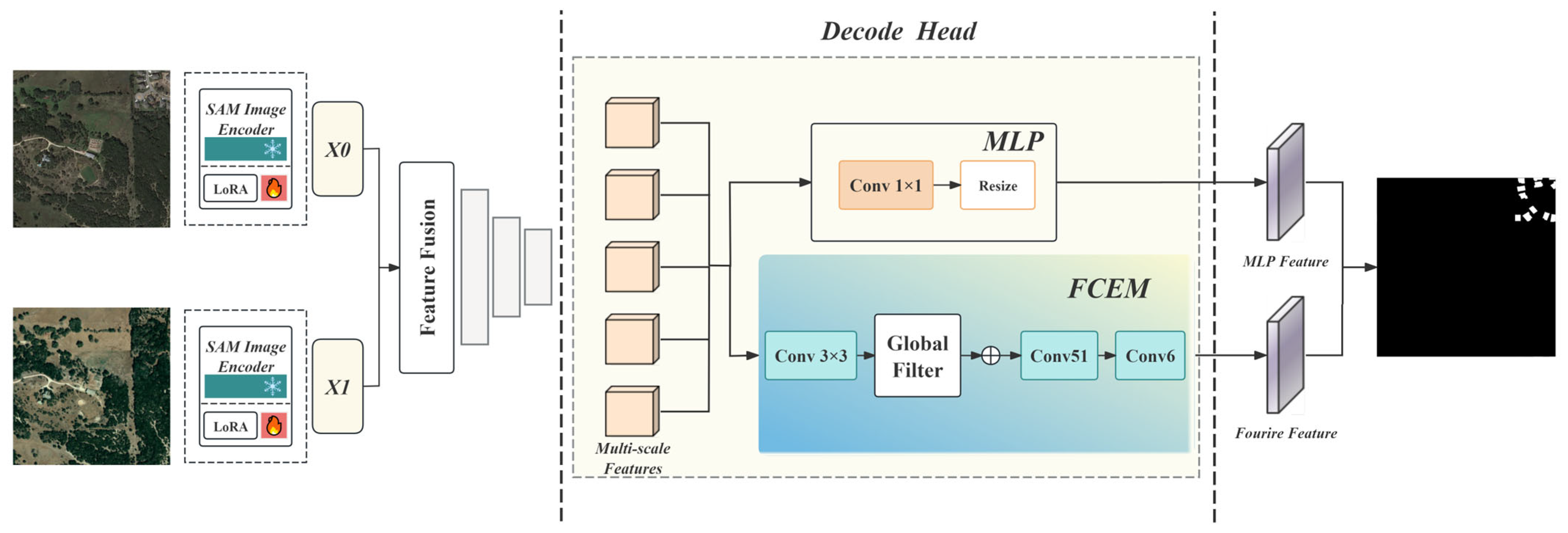

The overall structure of the SAM fine-tuning adaptation RSCD method based on Fourier frequency domain analysis difference reinforcement (SAM-FDN) proposed in this article is shown in

Figure 1.

The entire processing flow begins with the input of bi-temporal remote sensing images. First, the two-phase images are concatenated and fed into a SAM-based feature encoder to extract deep semantic features. To mitigate the domain gap between natural images and remote sensed images, a LoRA strategy is employed for efficient fine-tuning of the SAM encoder. While keeping the pre-trained weights frozen, a small number of trainable parameters are introduced in the multi-head attention layers to achieve precise adaptation to domain-specific features. The multi-scale features output by the encoder are first fed into the bi-temporal feature fusion module. With the help of adaptive correlation modeling, this module enables deep interaction and difference alignment of bi-temporal semantic features, thereby highlighting key change regions and modeling cross-temporal correspondences. The fused features are then sent to the decoder to progressively restore spatial resolution.

Significantly different from traditional change detection models, SAM-FDN integrates an FCEM within its decoder. This module maps spatial domain features to the frequency domain using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and performs adaptive amplitude and phase modulation on the spectral representation using a learnable complex weight matrix. The FCEM can explicitly enhance true change signals in the frequency dimension while effectively suppressing background interference caused by illumination, cloud shadows, atmosphere, and other factors.

The frequency-enhanced features are then fused with the original spatial domain features via residual connections, achieving complementary synergy between frequency and spatial domain information. Finally, the multi-scale decoder constructs a pyramid structure through cascaded upsampling operations and lightweight perceptron modules, outputting the final change probability map. The entire network supports end-to-end training and is optimized using binary cross-entropy loss, fully exploiting the complementary advantages of SAM’s semantic generalization ability and the frequency-domain modeling mechanism, significantly improving change detection accuracy and robustness in complex remote sensing scenarios while maintaining computational efficiency.

2.2. Efficient Fine-Tuning of SAM Encoder with LoRA

Adapting SAM to downstream tasks often requires fine-tuning, but updating all model parameters (full fine-tuning) is computationally prohibitive due to the massive number of parameters and high GPU memory requirements. To address this challenge, an efficient and parameter-saving fine-tuning technique, LoRA, is employed.

The core idea of LoRA is to freeze the pre-trained model weights and inject small, trainable rank-decomposition matrices into specific layers of the model architecture. For a pre-trained weight matrix

, its update during fine-tuning is represented by a low-rank matrix,

. Instead of training the full

, LoRA approximates it with two smaller matrices,

and

, where the rank

. The forward pass is then modified as:

During training, remains frozen, and only the parameters of matrices A and B are updated. This drastically reduces the number of trainable parameters. In our SAM-FDN model, we apply LoRA to the multi-head attention layers within the SAM image encoder. This approach allows us to effectively adapt the powerful features of SAM to the remote sensing domain while minimizing computational overhead and memory usage, making the fine-tuning process highly efficient.

2.3. Bi-Temporal Feature Fusion Module

The low-rank fine-tuning based feature fusion module is a core component in SAM-FDN for temporal information interaction, specifically designed to establish semantic correspondences between bi-temporal images, enhance the model’s perception of true changes, and suppress non-semantic interference. This module, through an adaptive weight modulation mechanism, enables the model to selectively integrate complementary information from different temporal phases, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of change detection.

2.3.1. Feature Fusion Module

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the Feature Fusion module operates on the outputs of the parallel SAM encoders. It takes the bi-temporal feature maps,

from the first time point and

from the second time point, as its direct inputs. Let the input features be

,

where B, C, H, and W represent the batch size, channel dimension, and spatial height and width of the feature maps, respectively. These two feature maps are then processed within the module to identify change regions.

2.3.2. Adaptive Correlation Modeling

To establish the spatial correspondence between bi-temporal features, the module first calculates the correlation between the features of the two temporal phases. The features of the two temporal phases are concatenated along the channel dimension:

A correlation weight map is generated through a learnable channel compression layer:

where conv1×1 denotes the convolution operation and σ denotes the Sigmoid activation function. This weight map M encodes the correlation degree of bi-temporal features at each spatial location, guiding subsequent feature interactions.

2.3.3. Bidirectional Feature Enhancement Mechanism

Based on the calculated correlation map, the module implements a bidirectional feature enhancement strategy. Features from each temporal phase receive complementary information from the other temporal phase through a weighted fusion mechanism:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication, and

is a lightweight feed-forward enhancement network, defined as:

This bidirectional enhancement mechanism ensures that each temporal phase can selectively absorb useful information from the other phase based on correlation weights, enhancing the model’s ability to perceive changed regions. After bidirectional enhancement processing, the enhanced features of the two temporal phases are re-concatenated to form a complete bi-temporal representation:

Finally, the feature format is converted back to the original spatial-first arrangement:

2.4. Fourier Change Feature Extraction-Separation Module (FCEM)

The FCEM, as a core innovative component of SAM-FDN, aims to compensate for the shortcomings of traditional spatial domain methods, specifically their insufficient global modeling capabilities and ineffective suppression of complex background interference. The theoretical basis of this module stems from the intrinsic frequency characteristics of change information in remote sensing images. Specifically, changed regions typically manifest as high-frequency signals characterized by edge discontinuities and texture shifts, while stable background areas are primarily composed of low-frequency components. Fourier transform possesses inherent spectral decomposition capabilities, enabling the precise separation of mixed spatial signals into different frequency components. This provides an optimal theoretical framework for change detection tasks, which essentially require the separation of high-frequency information [

28].

Based on the aforementioned frequency domain analysis paradigm, the FCEM employs FFT to map the fused bi-temporal feature representation into the frequency domain. Subsequently, a learnable complex weight matrix is introduced to perform adaptive modulation on the frequency domain representation, selectively amplifying high-frequency components related to changes while suppressing low-frequency interference from invariant information. This differentiated enhancement strategy for high and low-frequency components enables more precise capture and amplification of change signals. Finally, deep fusion of spatial and frequency domain features is achieved through residual connections, significantly improving the model’s change perception accuracy and robustness in complex scenes.

2.4.1. Overall Architecture of FCEM

Traditional convolution operations are limited by local receptive fields, making it challenging to capture global dependencies. While self-attention mechanisms can model long-range dependencies, their O(N

2) computational complexity becomes a bottleneck in high-resolution remote sensing image processing. Frequency domain transformation inherently possesses global modeling capabilities, and its computational complexity is merely O(NlogN), providing a theoretical foundation for efficient global feature learning [

29,

30].

More importantly, target changes in remote sensing images often exhibit distinct frequency characteristics: structural changes like building outlines primarily manifest in mid-to-high frequency components, while non-semantic interferences such as illumination and cloud shadows mainly affect low-frequency components. Therefore, Fourier frequency domain analysis can selectively enhance change-related frequencies while simultaneously suppressing environmental interference [

31].

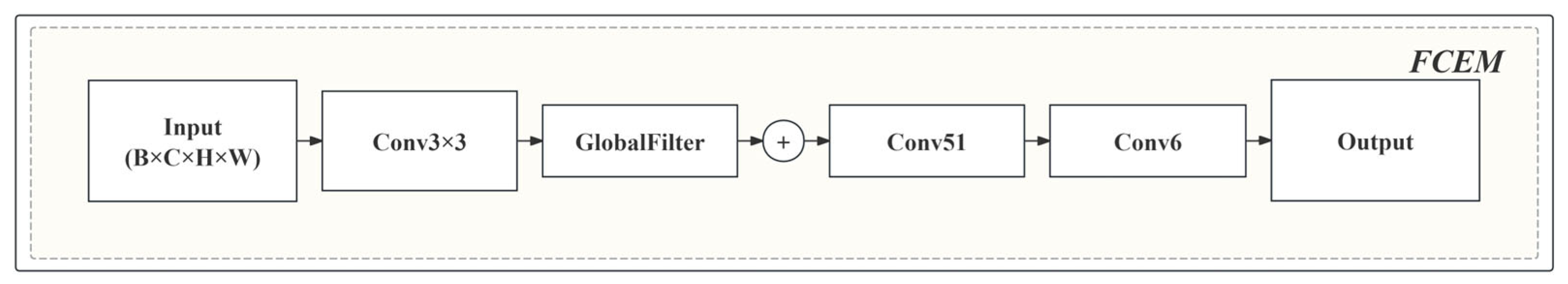

The FCEM module (

Figure 2) first performs channel compression on the input feature map

, reducing its dimensionality to an intermediate feature

through a 3 × 3 convolutional layer. Subsequently, this feature map is fed into the GlobalFilter module for frequency domain enhancement:

The FCEM module employs a residual connection to merge frequency domain features with the original features:

Then, further modeling and channel recovery are performed through a set of convolutional layers (Conv51, Conv6), finally outputting the enhanced feature map, which is then weighted and fused with the output of the MLP branch:

where γ is a learnable fusion weight parameter.

2.4.2. Global Frequency Domain Filter (GlobalFilter)

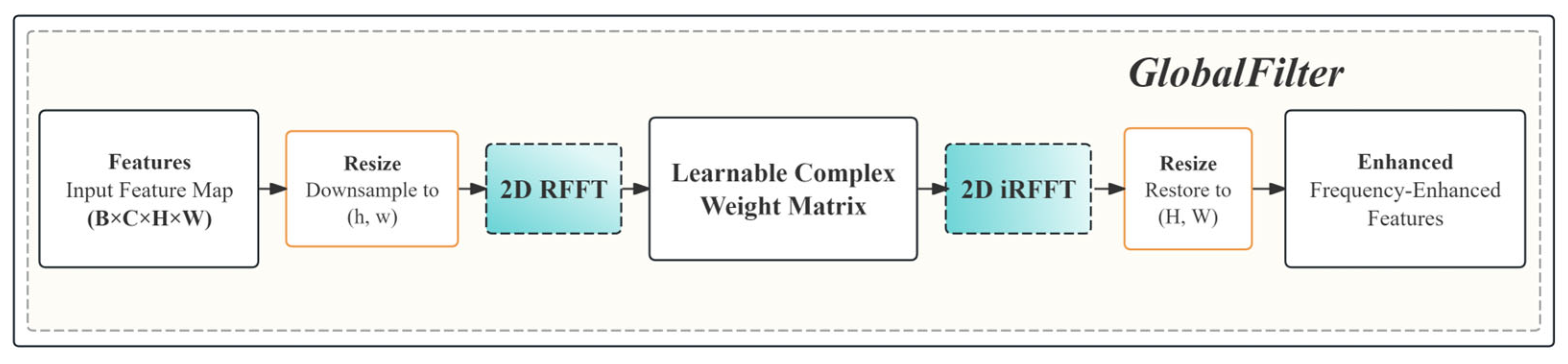

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the module achieves efficient global feature modeling by mapping spatial features into the frequency domain, applying an adaptive, learnable filter, and then transforming the result back into the spatial domain. Given the input feature (some formula), we first resize the feature map to a preset frequency domain processing dimension:

where

is the preset frequency domain processing dimension, typically

. For example, for a 512 × 512 input, the frequency domain processing dimension can be set to 14 × 8. This downsampling strategy can significantly reduce subsequent computational overhead.

The resized features are then mapped to the frequency domain via a 2D Real Fast Fourier Transform (RFFT):

where

. The use of real Fast Fourier Transform (rfft2) leverages the conjugate symmetry of real-valued signals, reducing computational load and storage requirements by approximately 50% compared to complex FFT. In the frequency domain, we introduce a learnable complex weight matrix

for adaptive modulation:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise complex multiplication. This mechanism enables the model to selectively enhance frequency components relevant to change detection while suppressing non-semantic frequency interference caused by changes in imaging conditions.

After frequency domain filtering, the features are transformed back to the spatial domain via an inverse FFT and restored to their original dimensions:

The computational complexity of the entire global filtering process is , which achieves significant computational savings compared to the complexity of the self-attention mechanism. In terms of spatial complexity, the storage requirement for the frequency domain representation is only , maintaining the same linear growth characteristic as the input features.

2.4.3. Learnable Complex Weight Design

The initialization and learning strategy of the complex weight matrix are crucial for model performance. We initialize the weight matrix with small random values:

This ensures stability during the initial training phase, preventing the frequency domain filtering from causing drastic perturbations to the original features. During training, the complex weights are optimized via standard backpropagation, with gradients effectively propagating through both FFT and inverse FFT, enabling end-to-end learning of the frequency domain filter.

3. Experiments

3.1. Experimental Datasets and Setup

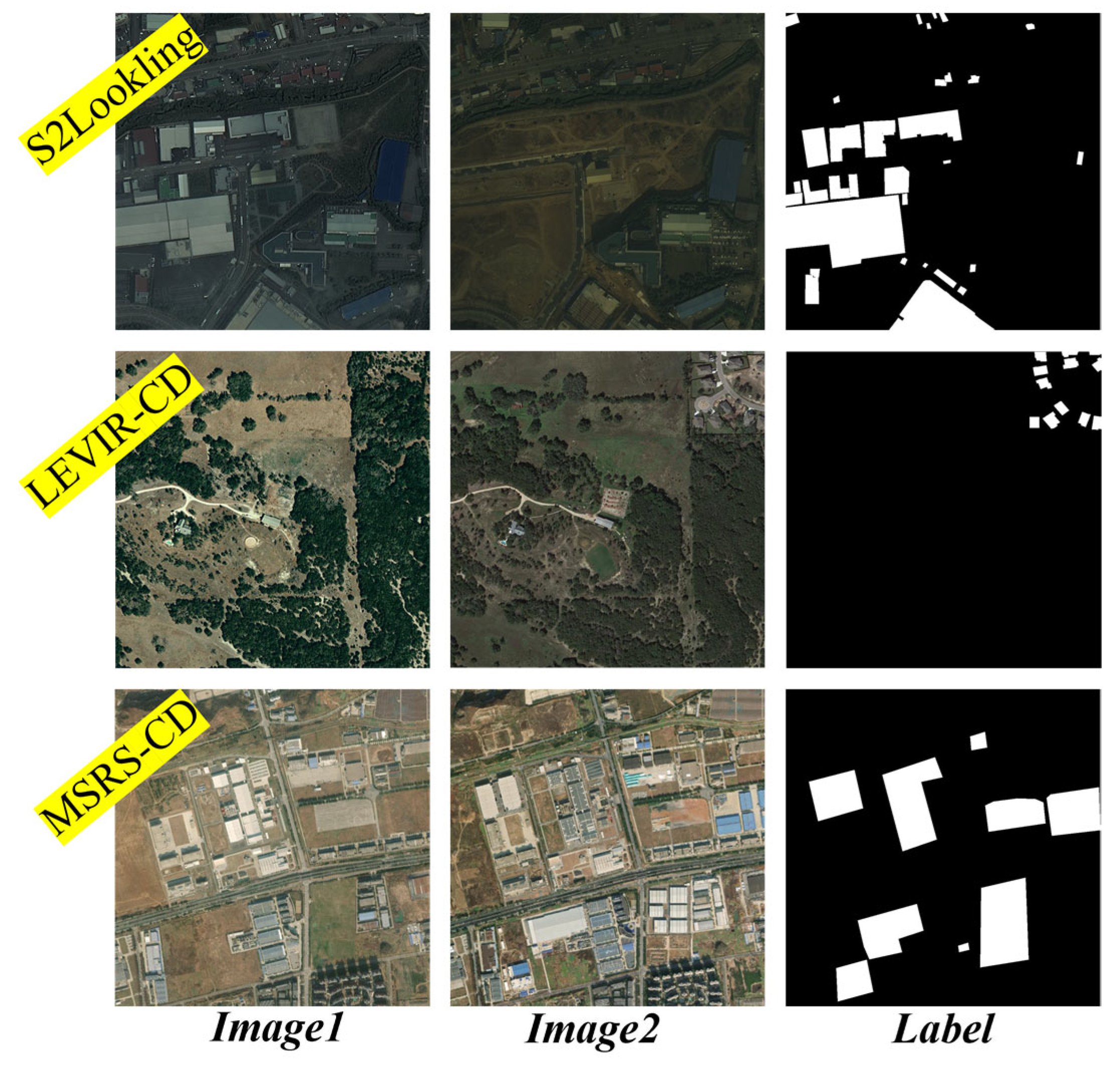

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted extensive experiments on three public RSCD benchmark datasets, including S2Looking [

32] and LEVIR-CD [

33], and MSRS-CD [

34] datasets.

The S2Looking dataset comprises 5000 pairs of bi-temporal satellite remote sensing images acquired between 2017 and 2020 by three satellites: Gaofen (GF), SuperView (SV), and Beijing-2 (BJ-2). Each image has 1024 × 1024 pixels and a spatial resolution ranging from 0.5 to 0.8 m. This dataset includes images from rural areas covering multi-angle off-nadir changes and contains over 65,920 building change annotations, making it one of the most challenging large-scale building change detection resources available.

The LEVIR-CD is a large-scale dataset specifically designed for building change detection tasks. It comprises 637 pairs of high-resolution (1024 × 1024 pixels, 0.5 m spatial resolution) bi-temporal remote sensing images, with time intervals between image pairs ranging from 5 to 14 years. This dataset focuses on the construction and demolition of buildings in urban and suburban scenes, covering various building types such as residential buildings, warehouses, and apartments. All change regions are manually annotated and reviewed by remote sensing professionals, resulting in over 31,000 instances of changed targets. The high annotation accuracy makes it widely used.

The MSRS-CD dataset is a multiscale RSCD dataset introduced to address the limitations of existing datasets, which often lack diversity in change target sizes and types. It comprises 842 pairs of high-resolution remote sensing images collected from southern Chinese cities between 2019 and 2023. Each image has 1024 × 1024 pixels and a spatial resolution of 0.5 m. MSRS-CD features a more comprehensive set of change types, including new construction, suburban expansion, vegetation changes, and road construction. This diversity ensures a more uniform distribution of change instance sizes, effectively mitigating the size bias prevalent in other benchmarks.

Figure 4 shows an example of the bi-temporal images and the corresponding change label from the three popular datasets.

3.2. Experimental Setup

Experimental parameters are set as follows: batch size was set to 2, and the total training epochs were 300. The AdamW optimizer was used, with a learning rate of 0.004. The selection of these hyperparameters aims to effectively minimize the loss function and improve overall training efficiency. Experiments were conducted within a PyTorch 2.1.2 framework environment, on hardware equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti GPU with 16 GB of video memory.

For performance evaluation, we adopted four metrics: Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Intersection over Union (IoU). Specifically, a higher Precision value indicates a lower false positive rate, while a higher Recall value represents a lower missed detection rate. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, serving as a comprehensive evaluation metric that more fully reflects model performance. A higher IoU value indicates that the change detection results are closer to the ground truth. The detailed calculation formulas for the aforementioned evaluation metrics are as follows:

where TP, FP, and FN represent the number of true positive, false positive, and false negative samples, respectively.

3.3. Comparative Experiments on Different Methods

3.3.1. S2Looking Dataset Experimental Results

For a fair comparison with other methods, we strictly followed the official dataset split for the S2Looking dataset, which comprises 3500 pairs for training, 500 pairs for validation, and 1000 pairs for testing. All models were trained on the official training set, and the final performance evaluation was conducted on the official test set.

Figure 5 presents a comparison of change detection effects of different methods on the S2Looking dataset. From the visualization results, it can be clearly observed that the proposed SAM-FDN method exhibits a significant advantage in detecting the completeness of changed regions. Compared to traditional methods, such as C2FNet [

35] and HCGMNet [

36], SAM-FDN and SAM-CD [

22] can more completely detect the boundary contours of changed areas (see the red boxes in

Figure 5), effectively avoiding the common “holes” within changed regions that often appear in building construction and demolition scenarios with other methods. Furthermore, in terms of background noise suppression, SAM-FDN significantly reduces false positive detections compared to methods like HCGMNet [

36] and CGNet [

37], especially in areas prone to misdetection such as vegetation, shadows, and water bodies. These improvements are primarily attributed to the frequency domain feature learning, which can capture more global change patterns and enables explicit decoupling of real structural changes from background disturbances, overcoming the limitations of traditional spatial domain methods constrained by local receptive fields.

It is particularly noteworthy that SAM-FDN demonstrates stronger adaptability in the multi-view, non-uniform resolution scenarios unique to the S2Looking dataset. Traditional methods are often affected by geometric distortions when processing off-nadir images, leading to noticeable deformations and inaccuracies in detection results. However, by separating high-frequency change cues from low-frequency background information, and leveraging SAM’s global perception ability, our method better copes with the challenges posed by view changes and maintains stable detection performance under complex imaging conditions.

Table 1 provides a detailed quantitative performance comparison of different methods on the S2Looking dataset. The quantitative results show that SAM-FDN consistently outperforms other state-of-the-art methods across all key evaluation metrics. The F1-score reached 68.90%, which is a 4.57 percentage point increase over the best-performing baseline method, CGNet (64.33%). On the IoU metric, our method achieved 52.55%, surpassing the highest baseline score of 47.41% by 5.14 percentage points. Furthermore, our model obtained the best Recall (64.64%) and Precision (73.92%), demonstrating a superior balance between reducing missed detections and false alarms. This indicates that the proposed method is more effective at identifying true change regions in the complex scenarios presented by the S2Looking dataset.

The complex characteristics of the S2Looking dataset and the inherent advantages of frequency domain processing methods form a good match, which explains the significant performance improvement. Firstly, regarding the advantage in handling geometric distortions, S2Looking contains a large number of off-nadir images with varying off-nadir angles, introducing significant geometric distortions and perspective shifts. Traditional spatial domain methods, relying on local receptive fields, struggle to effectively handle these global geometric transformations. In contrast, Fourier transform enables explicit frequency-band decomposition, which highlights structural change information while suppressing background interference, thereby helping the model to better cope with challenges arising from view changes. Secondly, concerning multi-resolution adaptability, the non-uniform resolution of 0.5–0.8 m/pixel in the dataset poses a challenge for CNNs with fixed receptive fields. Frequency domain methods, as global operations, can naturally allocate information of different scales to corresponding frequency components. Finally, regarding robustness to illumination changes, the large illumination variations characteristic of S2Looking primarily affect the low-frequency components of the images, while true structural changes are more reflected in mid-to-high frequency components. The learnable complex weight matrix can selectively enhance change-related frequencies while simultaneously suppressing illumination interference.

3.3.2. LEVIR-CD Dataset Experimental Results

We strictly adhered to the official dataset splitting scheme, where the training set includes 445 image pairs, the validation set 64 pairs, and the test set 128 pairs. Compared to the significant improvements on the S2Looking dataset, the performance gains on the LEVIR-CD dataset are relatively limited, primarily due to differences in dataset characteristics. The LEVIR-CD dataset exhibits high baseline performance, with its uniform 0.5 m resolution, near-nadir viewing angles, and structured urban environment, allowing traditional methods to already achieve F1-scores above 92%. At such a high baseline performance, many methods face the challenge of diminishing returns. Despite the limited improvement, marginal contribution analysis shows that SAM-FDN still achieves consistent performance gains, mainly reflected in high-frequency components improving boundary detection accuracy; frequency selectivity mitigating seasonal interference; and global contextual modeling enhancing the ability to identify large building changes.

Figure 6 demonstrates the detection performance of different methods on the LEVIR-CD dataset. From the visual comparison, it can be observed that: (1) Boundary Accuracy: Our method exhibits higher precision in building boundary detection, with clearer and sharper edges; (2) Shape Preservation: For building changes with complex shapes, SAM-FDN can better preserve the original shape characteristics of the targets, reducing deformation and distortion; (3) Small Object Detection: In the detection of small-scale building changes, our method shows better sensitivity, capable of capturing subtle changes missed by other methods.

On the LEVIR-CD dataset, our method also achieved competitive performance, as shown in

Table 2. The SAM-FDN performed excellently in terms of F1-score (92.41%) and IoU (85.89%), surpassing the current advanced methods such as C2FNet [

39] (91.81%/84.86%) and SRCNet [

35] (92.2%/85.6%). Particularly noteworthy is that our method achieved comparable performance in Recall (91.71%) with state-of-the-art methods, while maintaining a leading edge in Precision (93.12%).

3.3.3. MSRS-CD Dataset Experimental Result

To further validate the generalization capability and multi-scale adaptability of our proposed SAM-FDN method beyond building-centric change detection, we conducted experiments on the MSRS-CD dataset. Unlike the LEVIR-CD and S2Looking datasets, which primarily focus on building changes, MSRS-CD encompasses a broader spectrum of change types, including new construction, suburban expansion, vegetation changes, and road construction. This diversity in change targets, combined with a more uniform distribution of change instance sizes, makes MSRS-CD a more challenging and representative benchmark for evaluating the robustness of change detection models in real-world scenarios. By testing on MSRS-CD, we aim to assess whether SAM-FDN can effectively handle not only structural changes in buildings but also more subtle and varied changes in complex environments, thereby demonstrating its broader applicability and scalability. The dataset is partitioned into training, validation, and testing sets in a 7:1:2 ratio, providing a substantial and balanced benchmark for evaluating the robustness and scalability of RSCD algorithms, particularly those designed to handle multiscale changes.

To visually evaluate the performance and robustness of different methods, a qualitative analysis was conducted on the MSRS-CD dataset.

Figure 7 shows the prediction results of six models—namely ChangeFormer, SAM-CD, AANet, VcT, EATDer, and our proposed SAM-FDN. The visual results clearly demonstrate that the SAM-FDN model exhibits superior capability in identifying change regions and extracting finer boundaries across the majority of complex scenes.

Specifically, in scenarios containing large areas of change, competing models such as ChangeFormer and VcT often generate a higher number of False Positives (FP, marked in red in the figures) or False Negatives (FN, marked in green in the figures). In contrast, SAM-FDN accurately covers the main body of the changed targets while effectively avoiding over-segmentation. Particularly in the complex urban area shown in the fourth row, SAM-FDN’s prediction is the closest to the Ground Truth (GT), featuring smoother and more continuous change boundaries and effectively suppressing background noise. These qualitative results strongly validate the effectiveness of the SAM-FDN model’s design.

The findings from the qualitative analysis are further strongly supported by the quantitative experimental data. As shown in

Table 3, the proposed SAM-FDN model achieves the best performance in both F1-score and IoU, reaching 78.07% and 64.03%, respectively. Since the IoU score is a crucial metric for measuring the overlap between predicted and true change regions, SAM-FDN’s significant improvement (4.6% higher than the second-best model) is highly consistent with its more precise boundary localization capability demonstrated in

Figure 7. Furthermore, SAM-FDN’s P (%) (81.01%) is also the highest among all models, indicating the highest accuracy for the predicted change pixels, which aligns with the observed phenomenon of the minimal number of FPs (red regions) in the visual results. Although EATDer shows outstanding performance in R (%) (84.17%), its lower P (%) (66.73%) and IoU (59.29%) suggest that while the model recalls a large number of changes, it simultaneously introduces more errors, i.e., an excessive number of false positives. Therefore, we can consistently conclude that our proposed SAM-FDN model demonstrates significant superiority in the change detection task, especially in complex scenarios and fine-boundary recognition.

Beyond the qualitative and quantitative comparisons, this paper also evaluates the training efficiency of the model.

Table 4 presents the results of a comparative analysis between the proposed SAM-FDN and SAM-CD, each trained for 50 epochs on the MSRS-CD dataset. All experiments were conducted on a system equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti GPU (16 GB VRAM).

Although SAM-FDN, which is built upon the ViT-L-based SAM, required more GPU memory, it completed 50 epochs in only 5 h and 40 min. In contrast, the comparison method based on FastSAM [

43] took 11 h and 46 min under the same conditions. These results demonstrate that, through an appropriate fine-tuning strategy, our method achieves a favorable balance between computational cost and detection performance.

3.3.4. Cross-Dataset Performance Comparison and Analysis

By comparing the experimental results across the three datasets—LEVIR-CD, S2Looking, and MSRS-CD—we can observe a general complexity–model capacity relationship [

44]: the performance of a method tends to align with the diversity and difficulty level of the dataset. As shown by the F1-score comparisons in

Table 5, the more diverse and challenging characteristics of the S2Looking and MSRS-CD datasets allow the frequency-domain modeling strategy to better manifest its advantages. For the LEVIR-CD dataset, which features uniform resolution and relatively structured urban scenes, existing methods already achieve strong baseline results. Accordingly, the improvement brought by the frequency-domain mechanism is moderate but consistent, demonstrating the stability and adaptability of the proposed approach across datasets with varying levels of complexity.

From a technical perspective, the frequency-domain representation provides an inherent advantage in handling images containing periodic textures, complex spatial structures, and scale variations [

45]—properties that are reflected to different extents in all three datasets. For instance, S2Looking emphasizes geometric distortions and illumination diversity, while MSRS-CD introduces heterogeneous change types and significant scale variability. The consistent improvements across these datasets demonstrate that the proposed SAM-FDN framework can effectively capture both large-scale structural transformations and fine-grained semantic changes by leveraging complementary spatial- and frequency-domain cues.

These observations suggest that frequency-domain modeling is particularly beneficial for complex and diverse RSCD scenarios. By integrating spatial and frequency information, SAM-FDN provides a coherent and adaptable framework that maintains stable performance under varying imaging conditions and scene complexities, offering valuable guidance for future RSCD research.

3.4. Ablation Studies

3.4.1. Ablation Experiments on the S2Looking Dataset

In this section, ablation studies were conducted on a more challenging dataset (i.e., S2Looking Dataset) to analyze the effectiveness of the LoRA fine-tuning strategy and FCEM. For systematic evaluation, the process started with a baseline using a non-fine-tuned (frozen) SAM backbone, followed by the progressive addition of the proposed components; results are detailed in

Table 6.

The analysis begins with the baseline model (Row 1), where a frozen SAM backbone is used without any fine-tuning or the FCEM module. This configuration achieved an F1 score of 67.72%. On this more complex dataset, we observed that adding the individual components yielded more nuanced results. When only the LoRA fine-tuning strategy was applied (Row 3), the F1 score improved to 68.40%, and notably, the Recall saw a significant increase from 64.86% to 69.08%. This suggests that adapting the foundation model is crucial for identifying a greater number of true change regions, even if it slightly reduces precision.

In a parallel experiment, adding only the FCEM to the baseline (Row 2) also improved the F1 score to 68.19%. This demonstrates that the frequency-domain analysis is effective at enhancing change features and improving overall performance, independent of backbone fine-tuning.

Finally, our full model (Row 4), which integrates both LoRA and FCEM, achieved the highest F1 score of 68.90% and the highest IoU of 52.55%. It is particularly noteworthy that the full model attained a Precision of 73.92%, significantly outperforming all other configurations. This indicates a powerful synergistic effect: while LoRA is key to improving recall and capturing more potential changes, the FCEM works in concert to refine these features, suppress noise, and ultimately boost precision, leading to the best overall balance and the most accurate detection results.

3.4.2. Visual Analysis of the FCEM’s Effectiveness

To further investigate the specific impact of the FCEM on the model’s internal feature representation on the S2Looking dataset, we conducted a visual analysis of the intermediate feature maps. As shown in

Figure 8, we compare the feature map responses from a model equipped with the FCEM (FCEM √) against a variant without it (FCEM ×).

The visualization reveals a clear difference in feature quality. In the feature maps generated without the FCEM (middle column), the activations corresponding to the changed regions are often diffuse and scattered. The model produces blurry responses that lack precise spatial focus, and significant activation can also be seen in unchanged background areas, which could lead to false positives. In stark contrast, the feature maps enhanced by the FCEM (rightmost column) exhibit significantly sharper and more concentrated activations. The energy of the feature map is precisely focused on the true change targets, aligning closely with the ground truth labels. The boundaries of the changed objects are more clearly defined, and the activation in the surrounding background is effectively suppressed.

This visual evidence strongly corroborates our quantitative findings. It demonstrates that the FCEM plays a crucial role in refining the feature representation by enhancing the saliency of true change signals while simultaneously filtering out irrelevant background noise. This improved feature quality provides a more reliable basis for the subsequent decoder, leading to more accurate and robust change detection results.

4. Conclusions

To address the persistent issues of widespread false positives and missed detections in RSCD based on large model adaptation and fine-tuning, this paper proposes a SAM fine-tuning adaptation RSCD method based on Fourier frequency domain analysis difference reinforcement (SAM-FDN), which couples the SAM foundation model with a frequency domain-aware mechanism. This method leverages the feature extraction capability of the SAM and adopts a low-rank fine-tuning strategy to construct the model’s feature extraction backbone. It extracts features from remote sensing images captured at different time periods, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to recognize and interpret such time-series remote sensing images.

Furthermore, a FCEM is introduced, which applies Fourier transform to disentangle high-frequency variation information from low-frequency invariant content, amplify discriminative change features, and suppress redundant invariant ones, ultimately facilitating more robust and reliable change detection. Systematic evaluation results on three benchmark RSCD datasets demonstrate that SAM-FDN achieves superior performance compared to existing mainstream methods across various complex change scenarios. SAM-FDN exhibits stronger adaptability and discriminative power, particularly in aspects such as large-scale changes, boundary preservation, and background interference suppression. Further ablation studies strongly confirm the effectiveness of the proposed strategy—coupling the SAM foundation model with a frequency domain-aware mechanism—with particular emphasis on the FCEM’s crucial role in the frequency domain: it effectively enhances the separation of high-frequency change information and suppresses low-frequency invariant information.