Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A novel Attention Decision Forest (ADF) framework is proposed by integrating feature extractor, soft decision tree, and tree attention modules.

- The ADF successfully marries the interpretability of tree-based ensemble learning with the generalization capability of deep neural networks for surface soil moisture retrieval.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- This high-precision and interpretable ADF model provides a scientific tool for decision support in climate, ecological, drought, and water resource management applications.

Abstract

Surface soil moisture (SSM) plays a critical role in climate change, hydrological processes, and agricultural production. Decision trees and deep learning are widely applied to SSM retrieval. The former excels in interpretability while the latter outperforms in generalization, neither, however, integrates both. To address this issue, an attention decision forest (ADF) was developed, comprising feature extractor, soft decision tree, and tree-attention modules. The feature extractor projects raw inputs into a high-dimensional space to reveal nonlinear relationships. The soft decision tree preserves the advantages of tree models in nonlinear partitioning and local feature interaction. The tree-attention module integrates outputs from the soft tree’s subtrees to enhance overall fitting and generalization. Experiments on conterminous United States (CONUS) watershed dataset demonstrate that, upon sample-based validation, ADF outperforms traditional models with an R2 of 0.868 and a ubRMSE of 0.041 m3/m3. Further spatiotemporal independent testing demonstrated the robust performance of this method, with R2 of 0.643 and0.673, and ubRMSE of 0.062 and 0.065 m3/m3. Furthermore, an evaluation of the interpretability of the ADF using the Shapley Additive Interpretative Model (SHAP) revealed that the ADF was more stable than deep learning methods (e.g., DNN) and comparable to tree-based ensemble learning methods (e.g., RF and XGBoost). Both the ADF and ensemble learning methods demonstrated that, at large scales, spatiotemporal variation had the greatest impact on the SSM, followed by environmental conditions and soil properties. Moreover, the superior spatial SSM maps produced by ADF, compared with GSSM, SMAP L4 and ERA5-Land, further demonstrate ADF’s capability for large-scale mapping. ADF thus offers a novel architecture capable of integrating prediction accuracy, generalization, and interpretability.

1. Introduction

Surface soil moisture (SSM) is a critical parameter influencing the water and energy cycles and is indispensable in ecosystem functioning. Accurate retrieval of SSM information is essential for understanding climate change, characterizing hydrological dynamics, and guiding agricultural production [1]. Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) offers all-weather, high-resolution imaging capable of penetrating low to moderate vegetation canopies and shallow soil layers, while remaining highly sensitive to SSM variations. Consequently, SAR has become the primary tool for large-scale high-resolution SSM acquisition [2]. Traditional scattering model-based algorithms are usually considered the foundation for SSM retrieval [3], but the need for region-specific parameter calibration to simplify models [4] restricts their spatial and temporal generalization.

With rapid advances in remote sensing, data-driven machine learning algorithms have demonstrated strong potential for large-scale SSM retrieval [5]. By capturing complex nonlinear relationships among variables, they improve inversion accuracy [6]. Tree-based models, as typical data-driven approaches, offer high interpretability by revealing how each feature influences predictions via split rules and are widely used in the SSM domain. For example, Zhu [7] applied random forest (RF) and gradient boosting trees (XGBoost) models for SSM retrieval, while Song [8] employed a gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) for soil moisture monitoring. To visualize tree model interpretability more intuitively, the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) algorithm has become mainstream [9]. SHAP attributes model outputs to individual features by computing each feature’s marginal contribution across different feature subsets, thereby clarifying split rules [10]. However, tree model generalization remains constrained by the distribution and size of training datasets [7], leading to poor performance under data scarcity. To enhance SSM retrieval accuracy, ensemble methods such as stacking combine predictions from multiple weak learners (e.g., RF) [11]. Although stacking enhances SSM estimation performance, it introduces greater structural complexity and overfitting risk compared with individual models, which undermines interpretability and robustness in novel environments, resulting in lower explainability and limited generalization capability [12].

Deep learning algorithms have recently gained prominence for their ability to capture complex dependencies in large-scale feature sequences and to model nonlinear relationships by learning deep mappings between input variables and continuous outputs. Their hierarchical representations enable lower layers to capture raw features and each successive layer to extract increasingly complex patterns [13]. This capacity has led to growing application of deep learning in SSM retrieval [14]. In particular, self-attention mechanisms combined with deep architectures automatically weight input features and enhance prediction accuracy by extracting nonlinear interdependencies [15]. For example, Zheng [16] integrated multi-head attention with convolutional neural networks for soil moisture estimation, and Zhang [17] employed attention-based deep learning for spatial downscaling of soil moisture. Despite improved generalization, deep learning models remain “black boxes” with limited interpretability, compared to the intrinsic clarity of tree-based structures [18]. Tree-structured deep learning methods offer greater transparency. The Deep Neural Decision Forest (DNDF) simulates binary tree structures, retaining interpretability while achieving spatiotemporal generalization for large-scale SSM [19]. Its core component is the soft decision tree, which uses probabilistic routing at each internal node to direct outputs to child nodes until reaching leaves [20]. However, the soft decision tree alone exhibits limited dynamic weighting of node outputs, weak modeling of deep feature dependencies, and suboptimal overall performance.

Therefore, to address the multiple challenges of interpretability, generalization, and predictive performance, this study proposes a tree-structured deep learning model with self-attention mechanisms, namely the Attention Decision Forest (ADF). A dedicated feature extractor first learns multi-source information from datasets. Extracted high-dimensional features are then routed through soft decision tree via soft splits, preserving tree-based interpretability and enabling end-to-end optimization through differentiable node parameters. Finally, a Tree-Attention module dynamically weights leaf-node predictions to uncover deeper feature interactions and enhance large-area SSM retrieval accuracy. In addition, SHAP is incorporated into ADF. The objectives of this paper are (1) to assess algorithm accuracy under sample-based validation, (2) to evaluate generalization performance under spatiotemporal independent test, and (3) to evaluate the interpretability of the model and the contribution of quantitative factors to SSM.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the study area and datasets used for SSM retrieval. Section 3 introduces the ADF model and SHAP algorithm used for SSM retrieval in detail. Section 4 evaluates and analyzes the ADF model and machine learning methods and interpretable analysis of ADF combined with SHAP algorithm. Section 5 discusses other advantages of the ADF model. Section 6 concludes this study.

2. Study Area and Datasets

2.1. Study Area and In Situ Soil Moisture

The conterminous United States (CONUS, 25–49°N, 70–130°W) spans temperate and subtropical climate zones, with pronounced seasonal precipitation: concentrated heavy rainfall in summer and occasional frost with short freeze–thaw periods in winter. Land cover comprises a mosaic of cropland, forest, and grassland (Figure 1), and satellite-derived SSM exhibits marked spatial heterogeneity [21]. In land–atmosphere interactions, coupled effects of soil moisture with temperature and precipitation increase C-band microwave attenuation and broaden its dynamic range, creating favorable conditions for sensitivity analyses of retrieval algorithms [1]. Topographically, highlands on the east and west flanking a central plain facilitate extensive Arctic cold-air incursions in winter and Gulf of Mexico moisture advection in summer. Spring and autumn see frequent alternation of cold and warm air masses, intensifying climate variability and extreme events. Accurate quantitative precipitation forecasts are indispensable for disaster early warning, agricultural planning, and water resources management. As a critical land–atmosphere boundary condition, soil moisture not only directly regulates precipitation and atmospheric moisture supply via evaporation but also influences storm structure and rainfall distribution by altering sensible heat flux. Therefore, high-accuracy soil moisture data are essential for improving numerical weather prediction and validating remote-sensing retrieval algorithms [22].

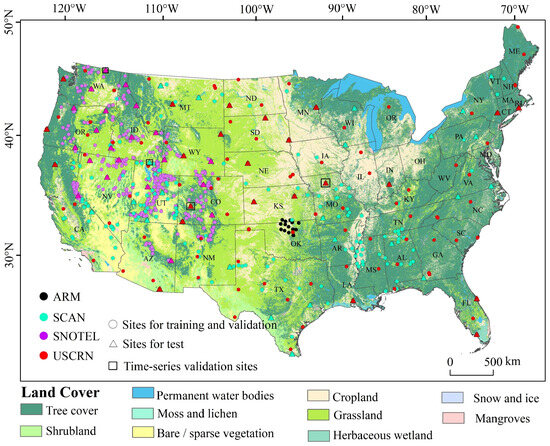

Figure 1.

Overview, detailed maps, and ground observation points of the CONUS region. The land cover is from the European Space Agency (ESA) WorldCover 10 m v200 product.

This study used in situ SSM datasets from the International Soil Moisture Network (ISMN), comprising four observation networks: ARM, SNOTEL, SCAN, and USCRN [23,24,25,26]. A total of 675 sites were included (Figure 1), each providing SSM at depths of 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 cm. Because C-band penetration rarely exceeds 5 cm, only the 5 cm records were extracted for the period from 2019 to 2023. Data quality was ensured using ISMN calibration flags. Subsequent plausibility filtering was then applied: (1) A global SSM saturation threshold of 0.6 m3/m3 [27] was applied, and all values outside the physically valid range of 0–0.6 m3/m3 were discarded; (2) to minimize the impact of frozen conditions on soil moisture retrieval, only records with a soil temperature > 0 °C at the 5 cm depth were retained (soil temperature is extracted from the 5 cm site during the same period). Measurements on the same date were averaged to produce daily near-surface soil moisture values. Site measurements were then matched to the 500 m MODIS grid, where multiple sites fell within one grid cell, an unweighted arithmetic mean was calculated to obtain a representative in situ SSM [7]. Finally, only those daily averages coincident with Sentinel-1 acquisition times were retained.

2.2. Predictor Attributes

The selection of predictor variables is critical to the performance of machine learning methods. Predictors in this study were chosen based on the radar scattering process and the meteorological-hydrological drivers of soil moisture, encompassing all factors relevant to SSM and aligning with many existing studies [28]. Table 1 lists the predictor datasets used for SSM retrieval, including Sentinel-1 SAR Ground Range Detected (GRD) data, MODIS data, ERA5 reanalysis data, and other static variables such as location attributes, soil texture, and topographic features.

Table 1.

Predictor variables used in this study.

Sentinel-1 SAR GRD data in both VV and VH polarizations were employed. In addition, local incidence angle (LIA), and day of year (DOY) were included as predictors to account for the strong influence of incidence angle on backscatter and the pronounced seasonality of soil moisture [7,29]. The GRD data were obtained from the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform and have undergone standardized preprocessing workflows by GEE, including thermal noise removal, radiometric calibration, and terrain correction. GEE combines ascending and descending orbital passes at a spatial resolution of 10 m and a temporal revisit interval of 5 or 7 days over the study area. GRD pixels covering all monitoring sites from 2019 to 2023 were extracted. In order to eliminate the influence of LIA caused by ascending and descending orbits, the backscatter coefficient of Sentinel-1 SAR GRD data is normalized by a theoretical method based on the optical lambert law [30].

Data from the Terra and Aqua Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) were used as predictors, including normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), land surface temperature (LST), and albedo.

NDVI, representing vegetation influence on SSM [31], was obtained from the MYD13Q1 and MOD13Q1 products (V6). These NDVI products are derived from atmospherically corrected bidirectional surface reflectance [32], with 250 m spatial and 16-day temporal resolution, and were accessed via the Google Earth Engine (GEE). The two NDVI products were composited to achieve an eight-day temporal resolution. Furthermore, cubic spline interpolation between the eight-day composites produced NDVI values for each Sentinel-1 acquisition date, and interpolated NDVI pixels covering all sites from 2019 to 2023 were extracted. LST strongly drives soil evaporation [33] and was sourced from the MYD11A1 product, which provides daily LST on a 1 km grid over 1200 × 1200 km at 1-day temporal resolution [34]. Cubic spline interpolation filled LST gaps for Sentinel-1 acquisition dates, and interpolated LST pixels for all sites from 2019 to 2023 were extracted. Albedo determines the fraction of incoming solar radiation reflected to the atmosphere, influencing surface energy balance; higher albedo reduces net radiation available for soil heating, decreases evapotranspiration, and enhances soil moisture retention [35]. The MCD43A3 Version 6 product provides 500 m resolution albedo at 16-day intervals, including directional-hemispherical reflectance (black-sky albedo) and bi-hemispherical reflectance (white-sky albedo) for MODIS surface bands 1–7 and three broad-spectral bands (visible, near-infrared, shortwave) [36]. This study used the black-sky shortwave broadband albedo from MCD43A3. Cubic spline interpolation on the GEE platform generated albedo values for Sentinel-1 acquisition dates, and these interpolated albedo pixels covering all sites from 2019 to 2023 were extracted.

Precipitation, the most direct driver of soil moisture changes, can markedly increase SSM during and after rainfall events. Hourly total precipitation was obtained from the ERA5-Land product at 0.1° resolution [37]. To represent average climatic conditions, the one-year mean precipitation prior to each DOY was used. Interpolated precipitation pixels covering all sites from 2019 to 2023 were then extracted.

Additional static variables included site latitude and longitude, which capture spatial heterogeneity [38]; soil texture, affecting water retention [39], for which sand and clay fractions were obtained from SoilGrids 2.0 at 250 m resolution; and topographic features-elevation, slope, and aspect-derived from the Copernicus DEM GLO-30 at 30 m resolution. Elevation influences temperature gradients, precipitation patterns, and vegetation types, thereby indirectly regulating soil moisture, while slope and aspect affect surface runoff, infiltration, and solar radiation distribution [40].

Predictor datasets were extracted from the GEE platform based on site coordinates for 2019–2023. A total of 675 sites were successfully matched (Figure 1). All variables were resampled via bilinear interpolation to the 500 m MODIS grid. The ARM network contributed 14 sites with 1811 samples, SCAN 168 sites with 21,735 samples, SNOTEL 386 sites with 59,315 samples, and USCRN 107 sites with 15,350 samples, yielding a combined in situ dataset of 98,211 samples. Each sample comprised predictor variables (Table 1) and corresponding target in situ SSM. Data from 2023 (17,627 samples) served as the temporal independent test set for assessing temporal generalization. From the 2019 to 2022 records, sites were randomly selected across states within the CONUS, with no more than five sites per state, producing a spatial independent test set of 68 sites (5987 samples). The remaining 607 sites (74,597 samples) were used for sample-based validation, with model accuracy assessed by 10-fold cross validation.

2.3. SSM Products for Intercomparison

This study also compared model-estimated SSM with three existing soil moisture products, ERA5-Land, SMAP Level 4 (SMAP L4), and GSSM. ERA5-Land, the land component of the ECMWF Reanalysis 5, provides 53 global, consistent variables related to terrestrial water and energy cycles, including soil moisture and land surface temperature, at 0.1° spatial and daily temporal resolution. The SMAP L4 soil moisture product is a merged dataset combining observations from the SMAP active-passive satellite, in situ measurements, and model outputs, offering 3-hourly SSM at 9 km × 9 km resolution [41]. GSSM delivers daily surface soil moisture (0–5 cm) at 1 km resolution for 2000–2020 [42]. All three products are accessible via the GEE platform. For evaluation, SSM was extracted at 0–7 cm depth from ERA5-Land and at 0–5 cm depth from SMAP L4 and GSSM. Temporally, ERA5-Land and SMAP L4 cover 2019–2023, whereas GSSM is limited to 2019–2020.

3. Methods

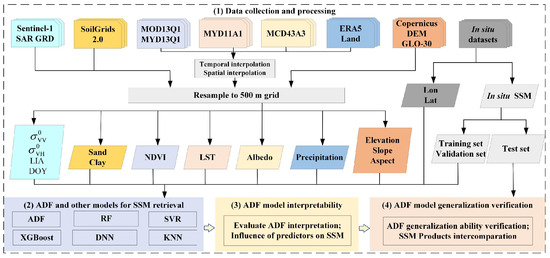

The workflow of this study is illustrated in Figure 2 and comprises the following steps. First, any temporal or spatial gaps in the raw datasets or products were filled by interpolation, and all data were resampled to the 500 m MODIS grid to ensure spatiotemporal consistency. Predictor attributes were then extracted and combined with in situ SSM to form the sample dataset. Following the data-splitting protocol in Section 2.2, the ADF model was compared with RF, support vector regression (SVR), XGBoost, deep neural network (DNN), and k-nearest neighbors (KNN) to assess its accuracy and generalization. SHAP analysis was then used to evaluate the interpretability of the ADF model alongside various other models (including ensemble learning and deep learning models) and to quantify the contribution of each input variable to SSM. Finally, the ADF-based SSM spatiotemporal distribution was mapped and compared with contemporaneous SSM products to evaluate the model’s practical applicability.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of this study.

3.1. ADF Model

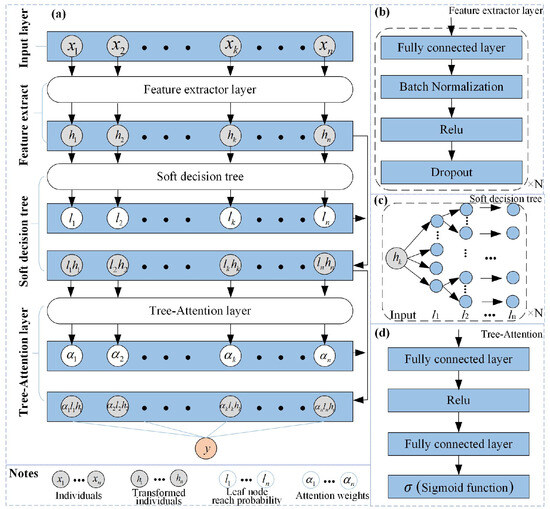

To combine the interpretability of tree models with the strong generalization of deep learning, this study designs an ADF model. ADF first maps multi-source features into a high-dimensional, separable latent space via a front-end neural network to capture the nonlinear relationships between predictors (e.g., vegetation indices, meteorological variables) and SSM. Within this feature space, the soft decision tree forest learns local rules through probabilistic branching, retaining both the interpretability of tree structures and the representational power of deep models. A Tree-Attention module then dynamically weights the outputs of multiple trees, allowing the model to focus on the most suitable submodels for different geographic or spatiotemporal contexts. This design reduces prediction error while enhancing robustness to spatial heterogeneity and temporal variability. As illustrated in Figure 3, ADF comprises a feature extractor, a soft decision tree forest, and a Tree-Attention module. The following sections provide detailed descriptions of each component.

Figure 3.

(a) Network structure of the ADF model, (b) unit structure of the feature extractor layer, (c) Unit structure of the soft decision tree, and (d) tree-attention layer.

3.1.1. Feature Extractor

Raw features often contain complex nonlinear relationships that are difficult to capture when fed directly into a model. The feature extraction network aims to project raw inputs into a higher-dimensional latent space with stronger discriminative power. As shown in Figure 3b, it consists of stacked blocks, each containing a fully connected layer, batch normalization, ReLU activation, and dropout. The fully connected layer uses an affine transformation to map low-dimensional inputs into a high-dimensional feature space, enhancing representational capacity. Batch normalization mitigates distribution shift during training, accelerates convergence, and improves stability. Dropout randomly deactivates neurons to prevent overfitting and boost generalization. This study employs two such blocks to increase model generalization and improve SSM retrieval in data-scarce regions.

3.1.2. Soft Decision Tree

Unlike the binary splits of traditional decision trees, a soft decision tree uses probabilistic splits, where the probabilities of left and right branching are determined by a sigmod function and need not sum to one (Figure 3c). The probability of a sample reaching a given leaf is obtained by multiplying the branching probabilities along the path from the root to that leaf. If the internal node at layer l with index ni(l) has an arrival probability μi(l)(h), then the probabilities of reaching its left and right child nodes are given by:

Here, h denotes a prediction sample, pn(h) denotes the arrival probability at the internal node n; μ2i−1(l+1) (h) and μ2i(l+1) (h) denote the arrival probabilities at its left and right child nodes, respectively. The output of the soft decision tree is defined as the sum of contributions from all leaves, that is, the probability-weighted expectation of the leaf values:

where μl(h) denotes the contribution from the l-th leaf, ω represents the probability weight of the leaf value, and f(h) is the output of the entire tree.

In contrast to classical ensemble methods such as random forest and XGBoost, the soft decision tree is fully differentiable and supports end-to-end SSM retrieval via gradient descent. Each tree conducts probabilistic splits in the high-dimensional latent space, combining the nonlinear representational capacity of neural networks with local interpretability at the leaf layer. A forest of multiple differentiable soft decision trees preserves the advantages of tree models in nonlinear partitioning and feature interaction while further improving fit and generalization through ensemble aggregation. In this study, five soft decision trees were implemented.

3.1.3. Tree-Attention

Each differentiable soft decision tree in the forest independently produces a prediction. The tree-level attention mechanism dynamically allocates weights to the t trees in the forest, thereby leveraging submodels most suited to the current input and improving overall fit and generalization. As shown in Figure 3d, the mechanism applies two layers of nonlinear mapping and normalizes the result via softmax to obtain the attention weight vector α(h), which is then used to compute the weighted sum yielding the SSM estimate:

Here, l represents the attention score for the l-th tree, and f(h) is the output of that individual decision tree.

3.2. Interpretability Analysis

The SHAP method was used to interpret the input features driving the ADF model. SHAP is a cooperative game-theoretic attribution technique that quantifies each feature marginal contribution to the prediction by computing its Shapley value, ensuring consistency and local fitting capability. In this study, SHAP was applied to ADF and to several other models, including ensemble learning and deep learning approaches primarily, to evaluate whether ADF offers superior interpretability and to quantify each input variable’s contribution to SSM. This analysis reveals the factors that most strongly influence SSM estimates and provides an interpretable view of the model’s decision process.

3.3. Comparative Evaluation Methods

To assess ADF’s potential for SSM retrieval, it was compared with five common machine learning methods. RF and XGBoost are both ensemble techniques, but their mechanisms differ. RF constructs multiple decision trees and predicts by majority voting, reducing overfitting risk and improving stability and accuracy [43]. XGBoost is a gradient boosting algorithm that sequentially fits weak learners to residuals, forming a robust regression model capable of capturing nonlinear relationships and offering flexible feature handling [44]. KNN predicts by identifying the k closest training samples and using their average value or majority class [45]. SVR employs kernel functions, such as the radial basis function, to manage complex data distributions and generally performs well on small datasets due to its strong generalization [46]. Compared to the aforementioned methods, DNN is a model that stacks multiple hidden layers to perform successive abstractions and nonlinear transformations, automatically extracting complex features from input data for prediction [47].

The hyperparameter ranges for all models are listed in Table 2. The optimal hyperparameters of the machine learning model are determined by cross-validation combined with grid search, including KNN (n_neighbors = 5), RF (max_depth = 20, n_estimators = 100), SVR (kernel = ‘rbf’), and XGBoost (n_estimators = 100, learning_rate = 0.001, max_depth = 20), were determined using cross-validation. The ADF model used a learning rate of 0.001, was trained for 100 epochs, and had 64 neurons per layer. The DNN used for comparison consisted of four fully connected layers followed by a dropout layer, with 64 neurons per layer; training settings were identical. Early stopping (patience = 10) was applied to both models to prevent overfitting.

Table 2.

Hyperparameter ranges of the models selected in this study.

To evaluate the accuracy and generalizability of the ADF model, sample-based validation, temporal independent test, and spatial independent test methods were employed. Statistical metrics were used for quantitative assessment of model performance. The following metrics are frequently employed [48]: the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), bias, and unbiased root mean square error (ubRMSE). Their expressions are:

where n is the number of samples, represents the measured value, represents the mean of the measured values, and xi represents the inverted value.

4. Results

This study employed the sample-based validation, temporal independent test, and spatial independent test to comparatively evaluate six models. Additionally, model interpretability was assessed using the SHAP algorithm, while the intercomparison and mapping performance were evaluated against other SSM products.

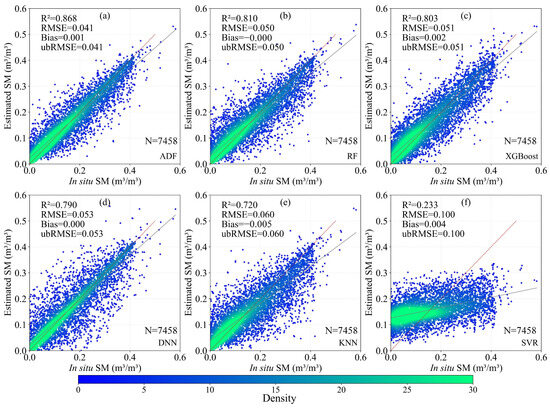

4.1. Sample-Based Validation

Figure 4 presents the results after sample-based validation. ADF model demonstrated the highest overall accuracy among all models, with an R2 of 0.868 and ubRMSE of 0.041 m3/m3. The two ensemble learning methods, RF and XGBoost, achieved the next highest accuracy, both yielding R2 of 0.803–0.810 and ubRMSE of 0.050–0.051 m3/m3. The DNN performed slightly worse than the ensemble methods, with R2 of 0.790 and ubRMSE of 0.053 m3/m3. In contrast to previous findings, KNN exhibited lower accuracy than both DNN and the ensemble methods, achieving an R2 of 0.720 and ubRMSE of 0.060 m3/m3. SVR showed the poorest performance, with an R2 of 0.233 and ubRMSE of 0.100 m3/m3.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot results based on sample-based validation: (a) ADF; (b) RF; (c) XGBoost; (d) DNN; (e) KNN; (f) SVR. The probability density is shown by the color of the points, the fitted line is shown in gray, and the 1:1 line is shown in red.

It is observed that SSM across the CONUS generally ranges from 0 to 0.5 m3/m3. At low SSM values, sample density is high for all models and predictions are slightly overestimated. At high SSM values, sample density is low and predictions are slightly underestimated. Since the ADF model’s fitted line showed closer alignment with the 1:1 line compared to the other five models, this overestimation or underestimation phenomenon was more pronounced in the other models, particularly at the low and high SSM value ranges.

4.2. Spatiotemporal Independent Tests

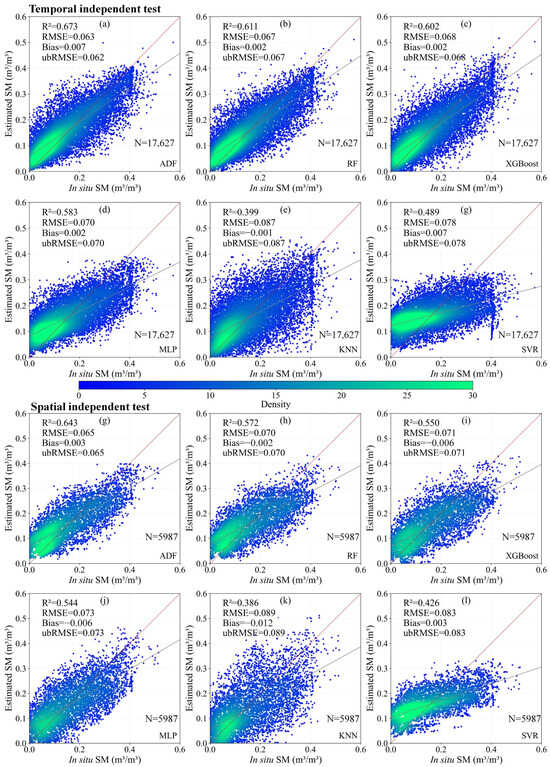

Figure 5a–f presents temporal independent test results for the six models. The ADF model achieved the best SSM retrieval, with R2 of 0.673 and ubRMSE of 0.062 m3/m3, which reached the accuracy target of approximately 0.06 m3/m3 [7,49,50]. The DNN followed, with R2 of 0.619 and ubRMSE of 0.066 m3/m3. The ensemble methods (RF and XGBoost) attained lower accuracy than DNN, with R2 between 0.602 and 0.611 and ubRMSE between 0.067 and 0.068 m3/m3. The MLP attained lower accuracy, with R2 of 0.583 and ubRMSE of 0.070 m3/m3. SVR ranked below ensemble methods but above KNN, with R2 of 0.489 and ubRMSE of 0.078 m3/m3. KNN performed worst, with R2 of 0.399 and ubRMSE 0.087 m3/m3. Compared to the sample-based results, most models exhibited accuracy degradation in temporal generalization. The ADF model’s R2 decreased by 0.195, with a corresponding ubRMSE increase of 0.021 m3/m3. DNN’s R2 dropped by 0.171, with its ubRMSE rising by 0.013 m3/m3. Ensemble methods experienced similar declines, with R2 reductions of about 0.199 to 0.201 and ubRMSE increases of 0.017 m3/m3. Conversely, SVR improved, with R2 increasing by 0.256 and ubRMSE decreasing by 0.022 m3/m3. KNN exhibited the largest degradation, with R2 falling by 0.321 and ubRMSE increasing by 0.027 m3/m3.

Figure 5.

(a–f) are the scatter plot results of the estimations and in situ SSM of ADF, RF, XGBoost, DNN, KNN, and SVR based on temporal independence tests; (g–l) are the scatter plot results of the corresponding models based on spatial independence tests.

Figure 5g–l shows spatial independent test results. ADF again achieved the best retrieval, with R2 of 0.643 and ubRMSE of 0.065 m3/m3. DNN yielded lower accuracy than ADF, with R2 of 0.593 and ubRMSE of 0.068 m3/m3. Ensemble methods performed slightly worse than DNN, with R2 of 0.550–0.572 and ubRMSE of 0.070–0.071 m3/m3. SVR ranked below ensembles but above KNN, with R2 of 0.426 and ubRMSE of 0.083 m3/m3. KNN performed worst, with R2 of 0.386 and ubRMSE of 0.089 m3/m3. From a spatial perspective, the decreasing trend in accuracy of all models is consistent with the temporal independent test.

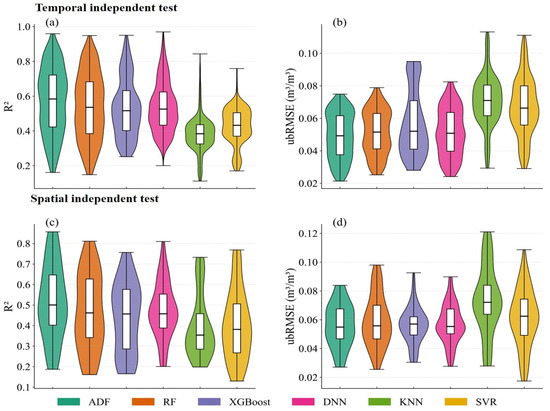

Figure 6a,b display median accuracy metrics across sites for the temporal independent test. ADF achieved optimal performance, with median R2 of 0.590 and median ubRMSE of 0.050 m3/m3. DNN outperformed the ensembles slightly, with median R2 of 0.540 and median ubRMSE of 0.051 m3/m3. RF and XGBoost followed with median R2 of 0.500–0.530 and median ubRMSE 0.052–0.054 m3/m3. KNN and SVR showed the worst median accuracy, with R2 of 0.400–0.420 and ubRMSE of 0.065–0.070 m3/m3. ADF maintained good accuracy at most sites. The 25th to 75th percentile ranges for R2 and ubRMSE were 0.430–0.700 and 0.038–0.062 m3/m3, with only minor performance drops at few sites, indicating strong generalization.

Figure 6.

(a,b) show violin plots for each in situ site based on temporal independent test for ADF, RF, XGBoost, DNN, KNN and SVR, respectively, with R2 and ubRMSE used to indicate site-level estimation performance for each model; (c,d) present the corresponding violin plots for the spatial independent test of the same models at each in situ site.

Figure 6c,d present spatial independent test medians. ADF again performed best, with median R2 of 0.500 and median ubRMSE of 0.052 m3/m3. DNN accuracy trailed the ADF, with median R2 of 0.460 and median ubRMSE of 0.054 m3/m3. RF and XGBoost followed with median R2 of 0.450–0.452 and median ubRMSE of 0.052–0.054 m3/m3. KNN and SVR yielded the worst medians, with R2 of 0.360–0.400 and ubRMSE of 0.060–0.070 m3/m3.

4.3. ADF Model Interpretability

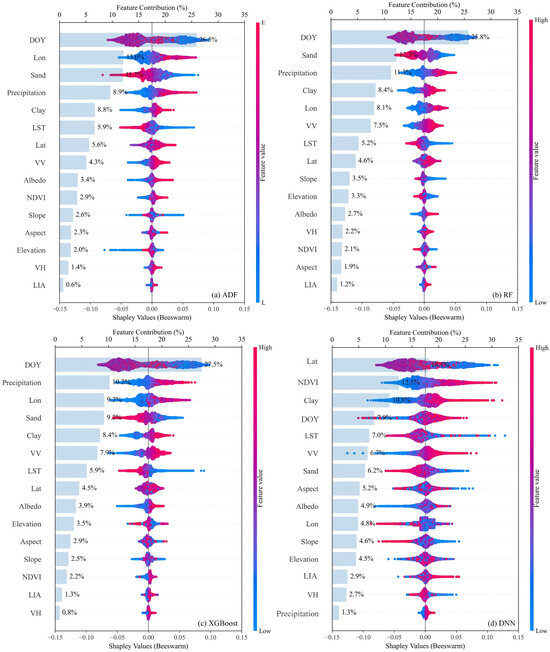

Figure 7 presents the SHAP interpretation results for the ADF model, tree-based models (RF, XGBoost), and the deep learning model (DNN). Due to the poor accuracy and generalization capability of KNN and SVR models in SSM retrieval task, their interpretability analyses were excluded.

Figure 7.

(a–d) show honeycomb plots of the SHAP values of different features using ADF, RF, XGBoost, and DNN. The color of the scatter points indicates the feature value. The bar chart shows the contribution of the feature to SSM.

The results indicate similar feature interpretability between the ADF and tree-based models, whereas the DNN shows a distinctly different characteristic. Among the major contributing features, DOY is identified as the most important factor to SSM retrieval in ADF, RF, and XGBoost, accounting for 26.5%, 25.8%, and 27.5% of the total contribution respectively, while being significantly lower at merely 7.9% in DNN. Precipitation ranks as the fourth most important contributor in ADF (8.9%), third in RF (11.3%), and second in XGBoost (10.2%), whereas it becomes the unreasonable least important factor in DNN (1.3%). Sand fraction ranks as the third most important contributor in ADF (11.7%), second in RF (12.3%), and fourth in XGBoost (9.2%), while contributing only 6.2% in DNN. Longitude ranks as the second most important contributor in ADF (13.0%), fifth in RF (8.1%), and third in XGBoost (9.2%), yet its contribution drops to 4.8% in DNN. Conversely, latitude emerges as the most important factor in the DNN (18.1%), whereas it plays a relatively minor role in ADF (5.6%), RF (4.6%), and XGBoost (4.5%). NDVI ranks as the second most important contributor in DNN (12.5%), whereas it is among the lowest-contributing factors in ADF (2.6%), RF (2.1%), and XGBoost (2.2%).

4.4. Intercomparison with Other SSM Products

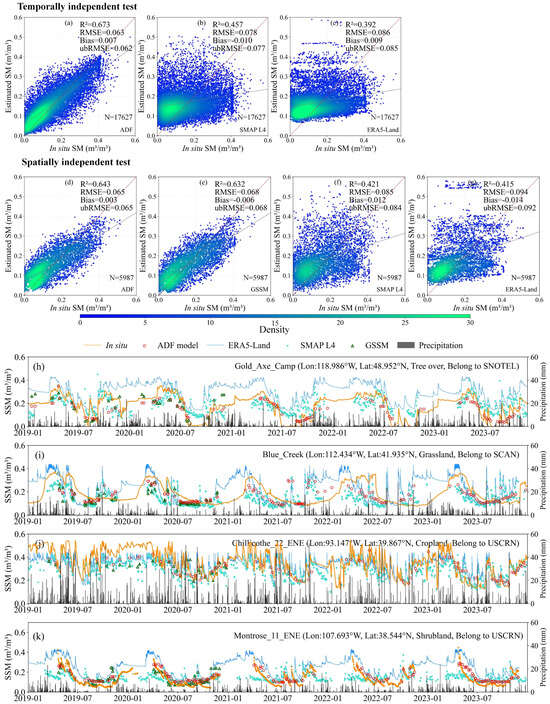

Figure 8a–g present scatter plots of the ADF model and related SSM products, including GSSM, SMAP L4, and ERA5-Land, against in situ SSM under temporal and spatial independent tests, respectively. Since the available GSSM product only extends until 2020, it is excluded from the temporal independent test for 2023. The results show that under both temporal and spatial independent tests, the ADF model outperforms the other products, with R2 ranging from 0.643 to 0.673 and ubRMSE between 0.062 and 0.065 m3/m3. By comparison, the accuracy ranking of the other reference products is GSSM > SMAP L4 > ERA5-Land, with R2 of 0.632, 0.421–0.457, and 0.392–0.415, and ubRMSE of 0.068 m3/m3, 0.077–0.084 m3/m3, and 0.085–0.092 m3/m3, respectively. Overall, under spatiotemporal independent test, the ADF model effectively captures the spatiotemporal variations of in situ SSM, with slightly higher accuracy than GSSM and substantially better performance than SMAP L4 and ERA5-Land.

Figure 8.

(a–c) are scatter plots of ADF, SMAP L4, and ERA5-Land with in situ SSM under temporal independent test; (d–g) are scatter plots of ADF, GSSM, SMAP L4, and ERA5-Land with in situ SSM under spatial independent test; (h–k) are time series comparisons of ERA5-land SSM, GSSM SSM, SMAP SSM, estimated SSM (ADF), and in situ SSM at four sites (Gold_Axe_Camp, Blue_Creek, Chillicothe_22_ENE, and Montrose_11ENE) selected from independent sites.

We further compared the SSM time series estimated by the ADF model with other products and in situ measurements at four independent sites named Gold_Axe_Camp, Blue_Creek, Chillicothe_22_ENE, and Montrose_11ENE (Figure 8h–k), where all products were systematically resampled to a consistent 500-m resolution grid using bilinear interpolation after excluding invalid values. Daily precipitation from ERA5-Land was also included to provide a preliminary examination of its relationship with the estimated SSM. Figure 8h–k show that the ADF model captures the temporal variations of in situ SSM and precipitation events more accurately than GSSM, SMAP L4, or ERA5-Land. The deviation between the ADF-estimated SSM and in situ measurements consistently remains below 0.05 m3/m3. Overall, although the model effectively captures the general SSM and precipitation trends, transient fluctuations or extreme variations can still lead to estimation deviations.

4.5. Retrieval Mapping of ADF

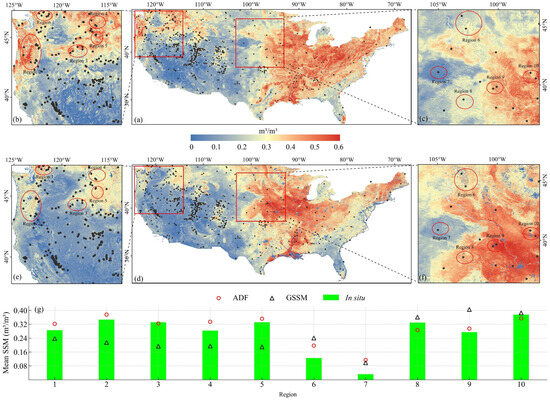

To evaluate the ADF model’s application potential, spatial maps of SSM over the CONUS were generated. Figure 9a–f present a comparison of the June 2020 composite mean SSM between the ADF and GSSM products.

Figure 9.

(a) displays the composite mean SSM for June 2020 predicted by the ADF model, with (b,c) providing zoomed-in views of selected regions, (d) presents the corresponding GSSM-predicted composite SSM, while (e,f) show enlarged sections of this output. Finally, (g) compares the aggregated mean SSM values from in situ sites with the estimates generated by both ADF and GSSM in the local regions with significant discrepancies between ADF and GSSM.

Both ADF and GSSM capture a pronounced east–west gradient in CONUS SSM, with higher values in the east (approximately 0.45–0.60 m3/m3) and lower values in the west (approximately 0.10–0.40 m3/m3). Although the spatial patterns are broadly similar, localized differences appear in the central and western regions. To quantify these biases, ten regions exhibiting significant discrepancies were further validated using in situ measurements. For each region, the aggregated mean SSM of June 2020 from in situ sites was computed and compared with the contemporaneous ADF and GSSM mean estimates to assess the relative performance of ADF and GSSM in local areas (Figure 9g).

Figure 9g shows that, except for regions 7 and 10, the ADF regional means are closer to the in situ means than those of GSSM, further demonstrating ADF’s advantage over 1 km products. Furthermore, even in regions 7 and 10, the mean SSMs of ADF and GSSM perform very small differences (both <0.01 m3/m3), which fall in the range of systematic error. In terms of geomorphological features, ADF resolves western mountain outlines more clearly than GSSM, as evidenced in Figure 9b,c,e,f.

In summary, the superior performance of ADF highlights the validity of high spatial resolution for capturing SSM dynamics in highly heterogeneous regions. In complex terrain and climatically diverse basins such as CONUS, low-resolution SSM products have clear limitations. The 500 m SSM maps produced by the ADF method outperform the 1 km GSSM product in both spatial resolution and accuracy.

5. Discussion

To combine the interpretability of tree structures with the generalization power of deep learning, ADF model was developed (Section 3.1). ADF comprises three components: a feature extractor, a soft decision tree, and Tree-Attention. The feature extractor employs multiple fully connected layers with nonlinear activations to learn high-order feature combinations, producing separable representations for the soft decision tree module [51]. The soft decision tree uses differentiable splits and probabilistic routing to weight all possible paths; when assembled into a forest and trained end-to-end with the neural network front end, it learns optimal split strategies and leaf predictions via gradient descent, combining nonlinear fitting capacity with model interpretability. The Tree-Attention mechanism then assigns dynamic weights to each tree, enabling adaptive focus on the most relevant submodels for each sample, which enhances both fitting accuracy and generalization under heterogeneous data conditions. Validation results confirm ADF’s superiority. Under sample-based validation (Section 4.1), ADF achieved R2 = 0.868 and ubRMSE = 0.041 m3/m3. The two ensemble methods (RF and XGBoost) followed closely, DNN trailed ensemble methods, KNN performed worse than DNN, and SVR showed the poorest performance. These findings indicate that ensemble methods generally outperform DNN on sample-based validation, and ADF combines their strengths to achieve the best results. Under temporal independent test (Section 4.2), ADF again led with R2 of 0.673 and ubRMSE of 0.062 m3/m3. DNN follows closely behind, and the performance of ensemble methods is slightly worse than that of DNN. SVR outperformed KNN in temporal independent test, whereas KNN, despite its better sample-based validation performance, deteriorated on independent sites. This reversal likely arises because KNN’s distance-based predictions are sensitive to high-dimensional, unevenly distributed features; local neighborhood structures may remain stable in sample-based validation but differ in independent sites, increasing prediction error. By contrast, SVR employs kernel functions and regularization to identify a globally optimal regression plane, offering greater robustness to noise [52]. The results of the spatial independent test were similar to those of the temporal independent test but were generally poorer. This likely reflects that SSM is strongly controlled by local topography, soil depth, vegetation, and drainage conditions; spatial heterogeneity is more complex than temporal variability, and relationships learned in the training region may not hold in new areas [53]. Notably, the DNN underperformed ensemble methods in sample-based validation but showed advantages in spatiotemporal independent tests. Ensemble methods excel at discrete partitioning and memorizing local patterns, which improves predictions for similar samples, whereas DNN, through hierarchical continuous representations and end to end regularization, are better suited for extrapolative generalization [54]. In terms of spatiotemporal generalization, ADF outperforms tree-based ensemble learning methods. This advantage stems from its hierarchical representation capability, which disentangles multi-source remote sensing inputs and extracts higher-order signals directly related to SSM, enabling the extraction of domain-robust features and thereby alleviating generalization issues caused by sample distribution shifts. Furthermore, compared to the traditional DNN that also possesses hierarchical representation capabilities, ADF’s tree component additionally applies probabilistic splitting rules to model subdomains and employs a tree attention mechanism to dynamically select the most suitable subtree for each sample. Consequently, ADF more effectively models complex nonlinear interactions than DNN, resulting in superior generalization performance.

In the interpretability analysis, SHAP was applied to the ADF model as well as to tree-based and deep learning methods to assess ADF’s interpretability and to quantify each factor’s contribution to SSM. Section 4.3 shows that ADF’s SHAP results closely resemble those of the ensemble methods and are broadly plausible, but demonstrate significant divergence from the DNN. Given that RF and XGBoost models are widely regarded as self-interpretable machine learning models, whereas DNN is considered non-interpretable, it is evident that ADF provides feature importance estimates with stability comparable to ensemble learning and markedly superior to DNN. Spatiotemporal factors (including DOY, longitude, and latitude) exert the strongest influence on SSM across all models. DOY denotes intra-annual seasonal cycles, characterizing the within-year redistribution of cumulative precipitation and seasonal variations in vegetation, evapotranspiration and albedo, thus reflecting the temporal heterogeneity of SSM [55]. Latitude and longitude capture climatic gradients and characterize the spatial redistribution of cumulative precipitation and spatial variations in vegetation, evapotranspiration and albedo, thus reflecting SSM’s spatial heterogeneity [56]. Environmental factors (including precipitation, LST, NDVI and albedo) follow, directly or indirectly regulating SSM [57,58]. This arises because, while these variables follow the aforementioned large-scale spatiotemporal heterogeneity, they still exhibit local-scale spatiotemporal variability. Among these environmental factors, NDVI contributes less because its effect overlaps with other environmental variables and much of the vegetation signal is already captured by them [59]. Soil texture, represented by sand and clay fractions, ranks third and affects water retention through pore structure and capillarity [60]. Topographic variables, including elevation, slope and aspect, show the lowest contributions. Topography is correlated with geographic position, land surface temperature, and precipitation [61], which reduces its marginal contribution. Additionally, local topographic variability is smoothed at coarser spatial resolutions, reducing its explanatory power for SSM. In microwave backscatter, VV polarization contributes certainly to SSM estimation [62], consistent with prior studies recommending VV for SSM mapping; by contrast, VH contributes weakly, mainly because strong canopy attenuation reduces the scattering energy reaching the soil surface. LIA’s contribution is also limited, mainly because VV and VH were normalized during preprocessing to remove ascending and descending orbit effects on LIA, thereby reducing LIA’s information content in the model.

To validate the practical application of the ADF model, its spatiotemporal SSM maps were compared with those of other products. Section 4.4 shows that ADF achieves markedly higher accuracy, with R2 of 0.643 and 0.673, and ubRMSE of 0.062 and 0.065 m3/m3. Figure 8h–k demonstrate that ADF captures temporal variations in in situ SSM and precipitation events more precisely than GSSM, SMAP L4 and ERA5-Land, notably reflecting peak rainfall and correspondingly elevated SSM. Notably, high SSM stations such as Gold_Axe_Camp, Blue_Creek, and Chillicothe_22_ENE are systematically underestimated, while low SSM stations such as Montrose_11ENE are systematically overestimated. This systematic bias results from the reduced sensitivity of the C-band SAR signal in low SSM areas and signal saturation in high SSM areas [63,64]. Moreover, the mean SSM map produced by ADF for June 2020 revealed a pronounced east to west contrast across CONUS (Figure 9): western SSM values ranged from 0.10 to 0.40 m3/m3, while eastern values ranged from 0.45 to 0.60 m3/m3. In many regions, ADF captured in situ SSM more accurately than the 1 km resolution GSSM product. Importantly, ADF more clearly delineated western mountain ranges, underscoring the value of high spatial resolution for capturing SSM dynamics in areas of strong spatial heterogeneity.

Certainly, the study has inherent limitations. Using point-based in situ data to validate satellite products introduces spatial representativeness errors, because heterogeneity within the satellite footprint (for example, soil texture, land cover, and vegetation) can produce substantial differences [65]. In addition, resampling uncertainty, particularly for Sentinel-1 products, arises because all datasets were resampled by bilinear interpolation to a common 500 m grid. Although this standardizes spatial resolution for consistent comparison, the process inherently smooths the data, and this smoothing may exacerbate spatial heterogeneity in SSM. Site sparsity also affects the results: station density in the study area is generally low, and a single station cannot fully represent within-pixel spatial heterogeneity, which constitutes an inherent limitation of the validation. Furthermore, the potential presence of agricultural irrigation adds complexity to interpreting SSM drivers and represents another inherent limitation for large-scale SSM modeling.

In short, ADF has achieved good results in both interpretability and generalization ability, and has great potential in practical applications.

6. Conclusions

Combining prediction accuracy, generalization, and interpretability in tree and deep learning models remains challenging. To address this, an ADF architecture-comprising a feature extractor, soft decision tree, and Tree-Attention module-was developed. Upon the sample-based validation, ADF achieved the highest accuracy with an R2 of 0.868 and ubRMSE of 0.041 m3/m3. Upon spatiotemporal independent tests, it outperformed the RF, XGBoost, DNN, and traditional machine learning models, yielding R2 of 0.643 and 0.673, and ubRMSE of 0.062 and 0.065 m3/m3. In interpretability analysis, SHAP results showed that ADF is more stable than deep learning methods such as DNN and is comparable to tree-based ensemble learning methods (RF and XGBoost). Both ADF and ensemble learning models emphasize the importance of spatiotemporal, environmental, and soil texture factors in large-scale SSM retrieval. Moreover, Compared with GSSM, SMAP L4 and ERA5-Land, the ADF spatial maps show superior fidelity, highlighting ADF’s capability for large-area SSM mapping.

Overall, the proposed ADF effectively balances prediction accuracy, generalization capability and interpretability, and shows strong promise for SSM prediction applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W. (Zuo Wang) and J.C.; methodology, J.C. and Z.W. (Zuo Wang); software, J.C.; validation, C.H. and Y.Y. (Yuanhong You); formal analysis, J.C. and Z.W. (Ziran Wei); investigation, J.C., Y.Y. (Yongtao Yang) and P.W.; resources, C.H., H.L. (Hao Liu) and H.L. (Hu Li); data curation, Y.Y. (Yongtao Yang), P.W., H.L. (Hao Liu) and Z.W. (Ziran Wei); writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.W. (Zuo Wang) and H.L. (Hao Liu); visualization, S.Z. and Z.D.; supervision, Z.W. (Zuo Wang); project administration, C.H. and H.L. (Hu Li); funding acquisition, C.H., Z.W. (Zuo Wang) and Y.Y. (Yuanhong You). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42471023), University Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Province (Grant No. 2023AH050137 and 2023AH050143), National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (Grant No. 202410370018 and 202410370014), and College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of Anhui Province (Grant No. S202410370017 and S202510370642).

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the datasets. The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the following resources available in the public domain: the field soil moisture data are available in the International Soil Moisture Network (ISMN) at https://ismn.earth/en, accessed on 1 September 2024; the satellite remote sensing images, DEM, soil texture, precipitation, and SSM products are available in the Google Earth Engine (GEE) at https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets, accessed on 1 September 2024.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank ISMN for providing the measured soil moisture data. The field soil moisture data can be obtained at https://ismn.earth/en, accessed on 1 September 2024. Other satellite remote sensing images and SSM products used in this study can be obtained through Google Earth Engine (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets, accessed on 1 September 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peng, C.; Zeng, J.; Chen, K.-S.; Li, Z.; Ma, H.; Zhang, X.; Shi, P.; Wang, T.; Yi, L.; Bi, H. Global spatiotemporal trend of satellite-based soil moisture and its influencing factors in the early 21st century. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 291, 113569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yuan, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Walker, J.P. Time series soil moisture retrieval from SAR data: Multi-temporal constraints and a global validation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 287, 113466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Shao, Q.; Sarukkalige, R.; Lü, H.; Zhang, J.; Bi, C.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y. Multi-layer grid-scale soil moisture estimation using spatiotemporal deep learning methods with physical constraints. J. Hydrol. 2025, 657, 133086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Chen, K.-S.; Cui, C.; Bai, X. A physically based soil moisture index from passive microwave brightness temperatures for soil moisture variation monitoring. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 58, 2782–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Rahmani, F.; Lawson, K.; Shen, C. A multiscale deep learning model for soil moisture integrating satellite and in situ data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL096847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Walker, J.P.; Shen, X. Stochastic ensemble methods for multi-SAR-mission soil moisture retrieval. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 251, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Dai, J.; Jin, J.; Yuan, S.; Xiong, Z.; Walker, J.P. Are the current expectations for SAR remote sensing of soil moisture using machine learning over-optimistic? IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4501815. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Yi, Y. Cascaded machine learning of soil moisture and salinity prediction in estuarine wetlands based on in situ internet of things monitoring. Water Resour. Res. 2025, 61, e2024WR038271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Jia, S.; Han, Y.; Zhu, W.; Lv, A. Enhancing Soil Moisture Prediction in Drought-Prone Agricultural Regions Using Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Approaches. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.C.; Ryu, D.; Lane, P.N.; Sheridan, G.J. Seasonal forecast of soil moisture over Mediterranean-climate forest catchments using a machine learning approach. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Su, Q.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Song, W.; Zhang, L.; Su, X. A Spatial Downscaling Framework for SMAP Soil Moisture Based on Stacking Strategy. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, Y. Soil Moisture Inversion Using Multi-Sensor Remote Sensing Data Based on Feature Selection Method and Adaptive Stacking Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, X. Remote sensing-based retrieval of soil moisture content using stacking ensemble learning models. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Dai, J.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, S.; Qin, T.; Walker, J.P. A cross-resolution transfer learning approach for soil moisture retrieval from Sentinel-1 using limited training samples. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 301, 113944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, P.; Tansey, K.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, F.; Liu, J.; Li, H. An interpretable wheat yield estimation model using an attention mechanism-based deep learning framework with multiple remotely sensed variables. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 140, 104579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Huang, J.; Meng, X.; Bai, Y. Prediction of Large-Scale Regional Evapotranspiration Based on Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Multi-Headed Self-Attention. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S. Spatial downscaling of ESA CCI soil moisture data based on deep learning with an attention mechanism. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, A.; Abdeslam, T.; Ayoub, N.; Lamane, H.; Ezzaouini, M.A.; Elbeltagi, A. An interpretable machine learning approach based on DNN, SVR, Extra Tree, and XGBoost models for predicting daily pan evaporation. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 327, 116890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bosch, J.; Olsson, H.H.; Koppisetty, A.C. Af-dndf: Asynchronous federated learning of deep neural decision forests. In Proceedings of the 2021 47th Euromicro Conference on Software Engineering and Advanced Applications (SEAA), Palermo, Italy, 1–3 September 2021; pp. 308–315. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Li, R.; Huang, C.; Xu, X.; Chen, H. User association and power allocation for user-centric smart-duplex networks via tree-structured deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 20216–20229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Hong, X.; Yao, L.; Zhang, X. Investigating the effects of spatial heterogeneity of multi-source profile soil moisture on spatial–temporal processes of high-resolution floods. J. Hydrol. 2025, 652, 132672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, Q.; Bi, H.; Qiu, J.; Zou, P. Evaluation of remotely sensed and reanalysis soil moisture products over the Tibetan Plateau using in-situ observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 163, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.S.; Mullens, T. A study of the relations between soil moisture, soil temperatures and surface temperatures using ARM observations and offline CLM4 simulations. Climate 2014, 2, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bitar, A.; Leroux, D.; Kerr, Y.H.; Merlin, O.; Richaume, P.; Sahoo, A.; Wood, E.F. Evaluation of SMOS soil moisture products over continental US using the SCAN/SNOTEL network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 50, 1572–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, G.L.; Cosh, M.H.; Jackson, T.J. The USDA natural resources conservation service soil climate analysis network (SCAN). J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2007, 24, 2073–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.E.; Palecki, M.A.; Baker, C.B.; Collins, W.G.; Lawrimore, J.H.; Leeper, R.D.; Hall, M.E.; Kochendorfer, J.; Meyers, T.P.; Wilson, T. US Climate Reference Network soil moisture and temperature observations. J. Hydrometeorol. 2013, 14, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, W.; Himmelbauer, I.; Aberer, D.; Schremmer, L.; Petrakovic, I.; Zappa, L.; Preimesberger, W.; Xaver, A.; Annor, F.; Ardö, J. The International Soil Moisture Network: Serving Earth system science for over a decade. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2021, 25, 5749–5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, D.; Mattia, F.; Balenzano, A.; Satalino, G.; Pierdicca, N.; Guarnieri, A.V.M. Sentinel-1 sensitivity to soil moisture at high incidence angle and the impact on retrieval over seasonal crops. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 7308–7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, E.; Sahebi, M.R. Surface soil moisture retrieval based on transfer learning using SAR data on a local scale. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 2374–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaby, F.T.; Moore, R.K.; Fung, A.K. Microwave Remote Sensing: Active and Passive. Volume 2—Radar Remote Sensing and Surface Scattering and Emission Theory; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Yan, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Luo, X.E.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B. Unraveling the interplay between NDVI, soil moisture, and snowmelt: A comprehensive analysis of the Tibetan Plateau agroecosystem. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 308, 109306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Tavares, J.; Roujean, J.-L.; Smets, B.; Wolters, E.; Toté, C.; Swinnen, E. Correction of directional effects in vegetation NDVI time-series. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Alizadeh, H.; Mojaradi, B. Land surface temperature assimilation into a soil moisture-temperature model for retrieving farm-scale root zone soil moisture. Geoderma 2022, 421, 115923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-H.; Li, Z.-L.; Liu, X.; Duan, S.-B. A global historical twice-daily (daytime and nighttime) land surface temperature dataset produced by Advanced Very High-Resolution Radiometer observations from 1981 to 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 2189–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, P.; Bohme, S.; Ericsson, N.; Hansson, P.-A. Albedo on cropland: Field-scale effects of current agricultural practices in Northern Europe. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 321, 108978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Lin, X.; Wu, X.; Bao, Y.; You, D.; Gong, B.; Tang, Y.; Wu, S.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Q. Validation of the MCD43A3 collection 6 and GLASS V04 snow-free albedo products over rugged terrain. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5632311. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Pan, Z.; Pan, F.; Wang, J.; Han, G.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, N.; Ma, S.; Chen, X. Influence patterns of soil moisture change on surface-air temperature difference under different climatic background. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Skaggs, T.H.; Ellegaard, P.; Bernal, A.; Scudiero, E. Relationships among soil moisture at various depths under diverse climate, land cover and soil texture. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzeminska, D.; Bloem, E.; Starkloff, T.; Stolte, J. Combining FDR and ERT for monitoring soil moisture and temperature patterns in undulating terrain in south-eastern Norway. Catena 2022, 212, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Fan, L.; Zhao, L.; De Lannoy, G.; Frappart, F.; Peng, J.; Li, X.; Zeng, J.; Al-Yaari, A.; Yang, K. A first assessment of satellite and reanalysis estimates of surface and root-zone soil moisture over the permafrost region of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Prikaziuk, E.; Niu, Z.; Su, B. Global long term daily 1 km surface soil moisture dataset with physics informed machine learning. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranza, C.; Nolet, C.; Pezij, M.; van der Ploeg, M. Root zone soil moisture estimation with Random Forest. J. Hydrol. 2021, 593, 125840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Fan, K.; Li, Y. An improved method for soil moisture monitoring with ensemble learning methods over the Tibetan plateau. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 2833–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthayakumar, A.; Mohan, M.P.; Khoo, E.H.; Jimeno, J.; Siyal, M.Y.; Karim, M.F. Machine learning models for enhanced estimation of soil moisture using wideband radar sensor. Sensors 2022, 22, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rains, D.; Lievens, H.; De Lannoy, G.J.; McCabe, M.F.; de Jeu, R.A.; Miralles, D.G. Sentinel-1 backscatter assimilation using support vector regression or the water cloud model at European soil moisture sites. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 4013105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Kwon, Y.; Nguyen, H.H. A stand-alone framework for predicting spatiotemporal errors in satellite-based soil moisture using tree-based models and deep neural networks. GISci. Remote Sens. 2025, 62, 2475572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.; De Lannoy, G.; Albergel, C.; Al-Yaari, A.; Brocca, L.; Calvet, J.-C.; Colliander, A.; Cosh, M.; Crow, W.; Dorigo, W. Validation practices for satellite soil moisture retrievals: What are (the) errors? Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 244, 111806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-B.; Van Zyl, J.J.; Johnson, J.T.; Moghaddam, M.; Tsang, L.; Colliander, A.; Dunbar, R.S.; Jackson, T.J.; Jaruwatanadilok, S.; West, R. Surface soil moisture retrieval using the L-band synthetic aperture radar onboard the soil moisture active–passive satellite and evaluation at core validation sites. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 1897–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, P.; Singh, G.; Das, N.N.; Entekhabi, D.; Lohman, R.; Colliander, A.; Pandey, D.K.; Setia, R. A multi-scale algorithm for the NISAR mission high-resolution soil moisture product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gaurav, K. Deep learning and data fusion to estimate surface soil moisture from multi-sensor satellite images. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veloso, M.F.; Rodrigues, L.N.; Fernandes Filho, E.I. Evaluation of machine learning algorithms in the prediction of hydraulic conductivity and soil moisture at the Brazilian Savannah. Geoderma Reg. 2022, 30, e00569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heße, F.; Zink, M.; Kumar, R.; Samaniego, L.; Attinger, S. Spatially distributed characterization of soil-moisture dynamics using travel-time distributions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, P.; Chen, L.; Pedrycz, W.; Ding, W. An integrated fusion framework for ensemble learning leveraging gradient boosting and fuzzy rule-based models. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 5771–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Ding, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. TRIMS LST: A daily 1-km all-weather land surface temperature dataset for the Chinese landmass and surrounding areas (2000–2021). Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2023, 2023, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Koehn, C.; Petrie, M.; Bradford, J.B.; Litvak, M.; Strachan, S. Seasonal precipitation and soil moisture relationships across forests and woodlands in the southwestern United States. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2020JG005986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.-Y.; Xu, H.-Y.; Mu, C.-C.; Wu, T.-H.; Li, W.-P.; Zhang, W.-X.; Streletskaya, I.; Grebenets, V.; Sokratov, S.; Kizyakov, A. Changes in different land cover areas and NDVI values in northern latitudes from 1982 to 2015. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2021, 12, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Qu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Tong, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Guo, J. Review of land surface albedo: Variance characteristics, climate effect and management strategy. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.F.; Short Gianotti, D.J.; Dong, J.; Trigo, I.F.; Salvucci, G.D.; Entekhabi, D. Tropical surface temperature response to vegetation cover changes and the role of drylands. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varamesh, S.; Mohtaram Anbaran, S.; Shirmohammadi, B.; Al-Ansari, N.; Shabani, S.; Jaafari, A. How do different land uses/covers contribute to land surface temperature and albedo? Sustainability 2022, 14, 16963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Ling, X.; Li, J. Exploring the Seasonal Comparison of Land Surface Temperature Dominant Factors in the Tibetan Plateau. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 10, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, K.; Wu, C.; Yu, B.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y. Layered Soil Moisture Retrieval and Agricultural Application Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Vegetation Suppression Technology: A Case Study of Youyi Farm, China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nativel, S.; Ayari, E.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, N.; Baghdadi, N.; Madelon, R.; Albergel, C.; Zribi, M. Hybrid methodology using Sentinel-1/Sentinel-2 for soil moisture estimation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Lindorfer, R.; Melzer, T.; Hahn, S.; Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; Morrison, K.; Calvet, J.-C.; Hobbs, S.; Quast, R.; Greimeister-Pfeil, I. Widespread occurrence of anomalous C-band backscatter signals in arid environments caused by subsurface scattering. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 276, 113025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zeng, J.; Chen, K.-S.; Ma, H.; Letu, H.; Zhang, X.; Shi, P.; Bi, H. Spatial representativeness of soil moisture stations and its influential factors at a global scale. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 63, 4402915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).