Impact of Volcanic Ash on Road and Airfield Surface Skid Resistance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

- Reduction of skid resistance on roads and runways covered by volcanic ash

- Coverage of road and airfield markings by ash

- Reduction in visibility during initial ashfall and any ash re-suspension

- Blockage of engine air intake filters which can lead to engine failure.

1.2. Skid Resistance

1.2.1. Surface Macrotexture and Microtexture

- Macrotexture defines the amplitude of pavement surface deviations with wavelengths from 0.5 to 50 mm.

- Microtexture is the amplitude of pavement surface deviations from the plane with wavelengths less than or equal to 0.5 mm, measured at the micron scale [43].

1.2.2. Road Skid Resistance

1.2.3. Airfield Skid Resistance

1.2.4. Volcanic Ash and Skid Resistance

- Particle size and surface area

- Composition and degree of soluble components

- Hardness and vesicularity

- Angularity and abrasiveness

- Wetness.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.1.1. Volcanic Ash

2.1.2. Test Surfaces

2.1.3. Painted Road Markings

- 1× application (180–200 μm thick) without retroreflective glass beads

- 1× application (180–200 μm thick) with retroreflective glass beads

- 4× applications (720–800 μm thick) without retroreflective glass beads

- 4× applications (720–800 μm thick) with retroreflective glass beads.

2.2. Skid Resistance Testing

2.2.1. Surfaces Not Covered by Ash

2.2.2. Surfaces Covered by Ash

- A similar procedure as adopted by the NZTA [80] whereby five successive swings are recorded, which do not differ by more than 3 BPNs and the SRV calculated. Between each swing, ash which has been displaced by the pendulum movement is replenished with new ash of the same type (and re-wetted if applicable) to maintain a consistent depth (and wetness). This test method mimics to some degree the effect of vehicles driving during ash fall, with ash settling on a paved surface and filling any voids left by vehicle tyres before the next vehicle passes. A mean SRV is calculated by repeating the test on all four sides of each asphalt slab.Skid resistance was tested using 1, 3, 5 and 7 mm thick wet and dry samples on SMA, and 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 mm thick samples on airfield concrete. Limitations in the quantity of samples prevented testing at 9 mm thick on SMA, and limitations in the quantity of rhyolite (HAT-RHY) in particular meant that testing was only conducted at 1 and 5 mm thickness on SMA for this ash type.

- Eight successive swings of the pendulum are taken over each ash-covered test surface area but ash is not replenished between each swing. For each swing, the BPN is taken to be the SRV, allowing the change in skid resistance to be observed through analysis of the individual results. If the original surface has been wetted, further water is applied between each swing. To some degree, this method represents vehicle movement over an ash-covered surface in dry or wet conditions, where ashfall onto the road surface has ceased. A mean SRV is calculated for each successive swing by repeating the test on all four sides of each asphalt slab where possible.

2.2.3. Cleaning

2.3. Macrotexture

2.3.1. Sand Patch Method

2.3.2. Image Analysis

- White paint was marked on the edge of the slabs in order to identify the same segment of the slab between each testing round.

- A Fuji Finepix S100 (FS) digital SLR camera (with settings: Manual, ISO 800, F6.4, 10-s timer) was mounted on a tripod directly above the asphalt slab.

- Halogen tripod worklights were used to illuminate the surface of the slab and all ambient light was blocked out using black sheeting before images were taken to keep lighting levels consistent between photos.

- Images were analysed for percentage coverage of ash by means of ‘training’ and ‘segmentation’ using ‘Ilastik’ and ‘Photoshop’ software.

2.4. Microtexture–Microscopy

3. Results and Discussion

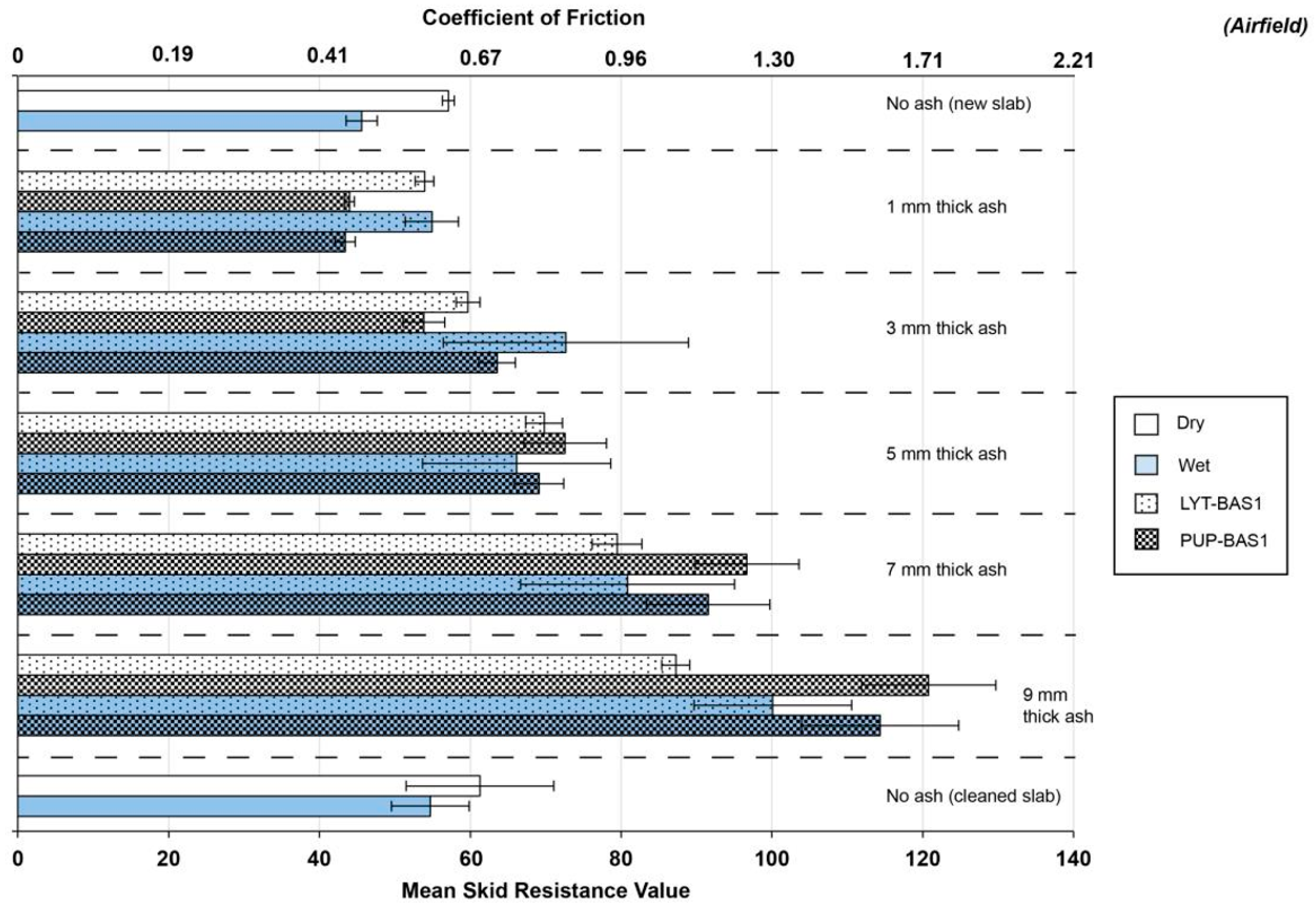

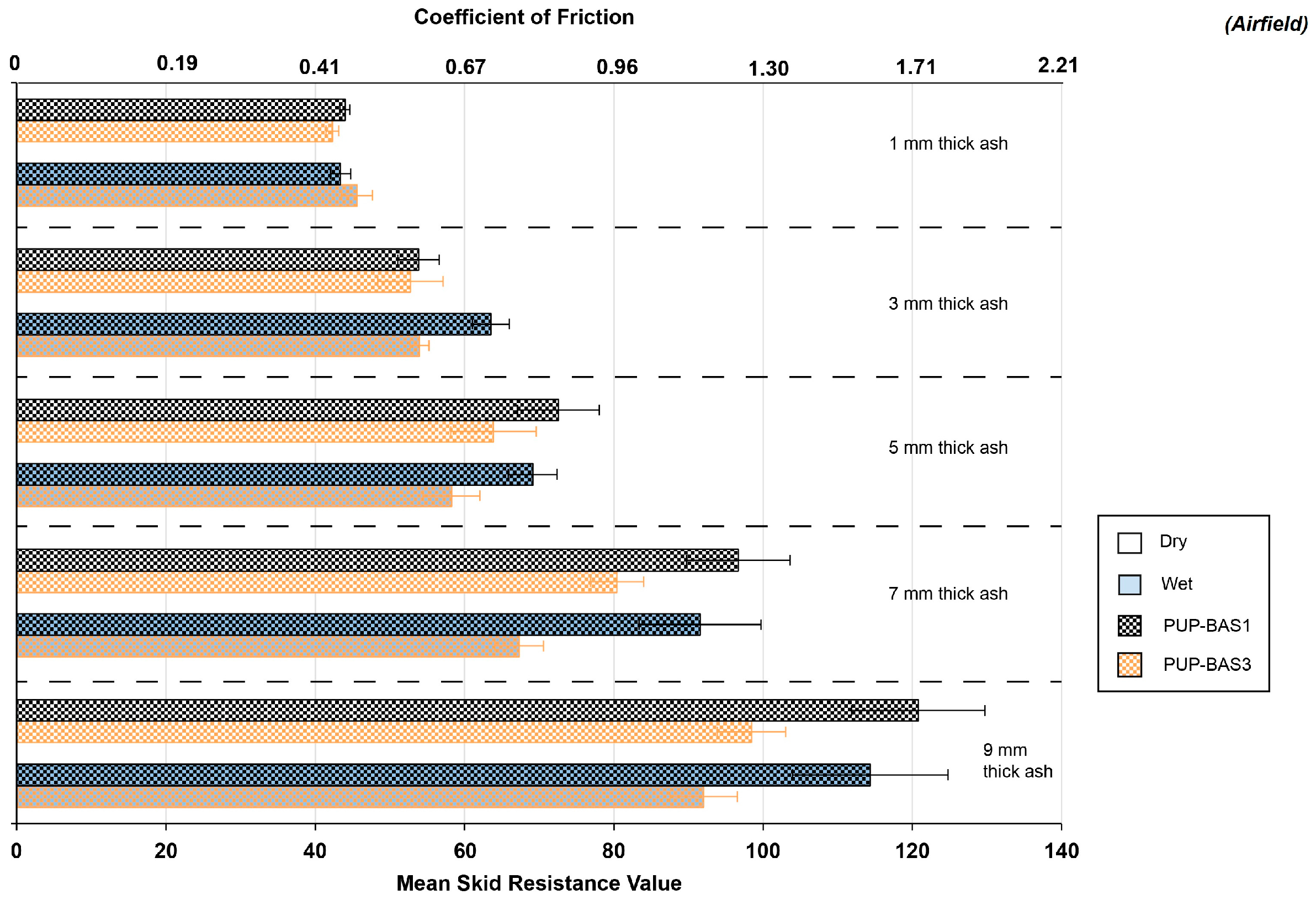

3.1. Consistent Depth

3.1.1. Ash Type and Wetness

3.1.2. Soluble Components

3.1.3. Ash Particle Size

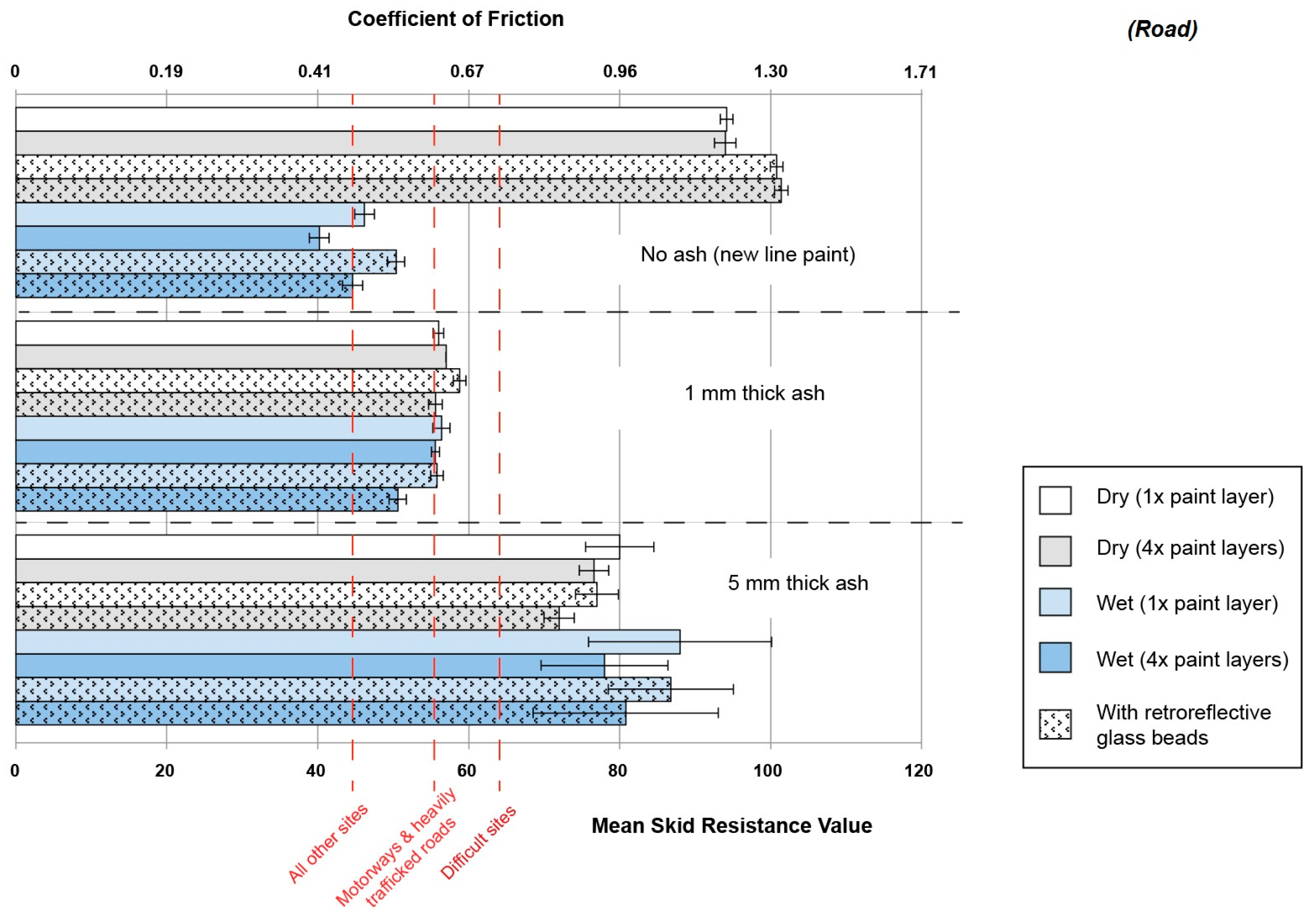

3.1.4. Line-Painted Asphalt Surfaces

3.1.5. Asphalt Comparison

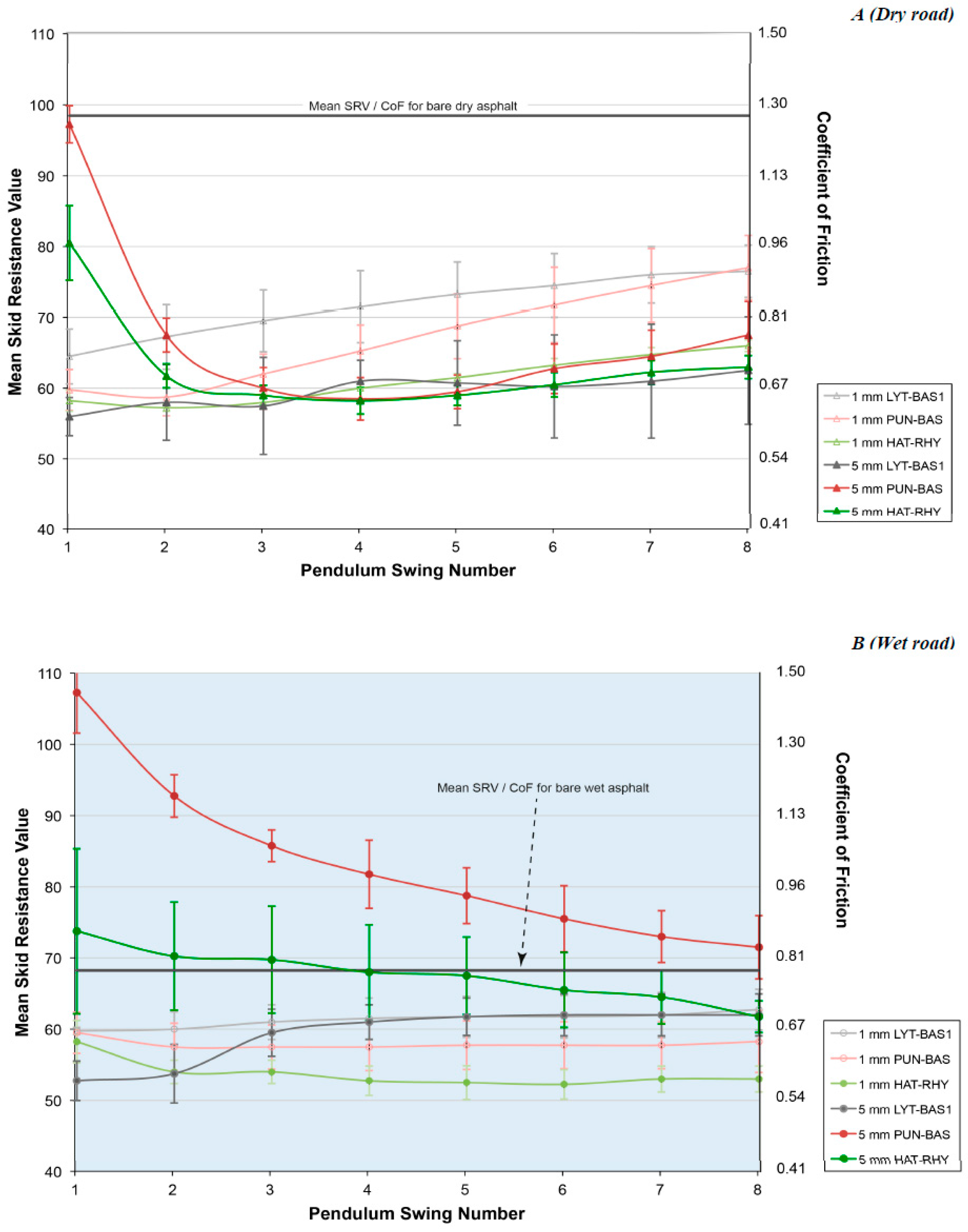

3.2. Inconsistent Depth

3.2.1. Ash Types and Wetness

3.2.2. Ash Particle Size

3.2.3. Soluble Components

3.2.4. Line-Painted Asphalt Surfaces

3.3. Surface Macro and Microtexture

3.3.1. Ash Displacement and Removal

3.3.2. Temporal Change of Skid Resistance on Bare Asphalt Surfaces

4. Conclusions

4.1. Key Findings

- Thin (~1 mm deep) layers of relatively coarse-grained ash, with ash type having little effect at this depth (average SRVs of 55–65).

- Thicker (~5 mm deep) layers of hard, non-vesiculated ash (average SRVs of 55–60).

- Ash of low crystallinity or containing a high degree of soluble components (average SRVs ~5 lower than for ash that has undergone substantial leaching).

- Line-painted surfaces that are either dry or wet but covered by thin layers of ash, particularly when paint does not incorporate retroreflective glass beads (average SRVs of ~55).

- There is little difference in skid resistance between bare airfield surfaces and those covered by ~1 mm of ash.

- Low crystalline ash containing high soluble components may result in SRVs of up to 20 less than non-dosed samples, particularly if the ash is thicker (~7–9 mm depth).

- Ash is more readily displaced on smoother airfield concrete than road asphalt causing SRVs to recover to ‘typical non-contaminated’ values at a faster rate with consistent traffic flow.

4.2. Recommendations for Road Safety

- During initial ash fall, vehicle speed (or advisory speed) should immediately be reduced to levels below those advised for driving in very wet conditions on that road, whether the surface is wet or dry. Wet ash is not necessarily more slippery than dry ash, at least initially.

- Fresh ash contains more soluble components, which results in lower skid resistance values than for leached ash. Therefore, it is important to advise motorists promptly of any restrictions.

- Particular caution should be taken on dry surfaces that become covered by coarse-grained ash as skid resistance will reduce substantially from what occurs on dry non-contaminated surfaces. The slipperiness of dry surfaces with such contamination may not be expected by motorists (skid resistance values will be similar as for wet fresh ash and slightly less than for wet non-contaminated conditions).

- Road markings may be hidden from view, impacting road safety through lack of visual and audio guidance of road features. Areas of road that are line-painted and covered in thin ash are especially slippery. Motorcyclists and cyclists in particular should take extreme care.

4.3. Airport Safety

4.4. Recommendations for Cleaning

- Brushing alone will not restore surfaces to their original condition in terms of skid resistance. Following simple brushing practices on asphalt roads, the macrotexture depth may be around one third less than the original depth and ~40% ash coverage may occur on the surface.

- If surfaces are dry and contaminated with dry ash, air blasting combined with suction and capture of loosened ash, is an effective way to remove ash from macrotextural pores. Minor quantities of ash may remain at the microtextural level although this is deemed too low to substantially affect skid resistance.

- If surfaces are wet, a combination of water spraying and brushing and/or air blasting (with suction and ash capture) is an effective way to remove most ash and restore surface skid resistance. However, large quantities of water are required and some ash will remain in the asphalt pore spaces, especially if low-pressure water is used. Care should be taken if using water for ash removal due to the potential for blockage of some drainage systems.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Element | Concentration (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ruapehu Crater Lake (100% Strength) | White Island Crater Lake (20% Strength) | |

| Aluminium (Al) | 370 | 965 |

| Boron (B) | 17.2 | 28.6 |

| Bromine (Br) | 10.8 | 44.2 |

| Calcium (Ca) | 909 | 823 |

| Chlorine (Cl) | 5568 | 19,452 |

| Fluorine (F) | 133 | 1518 |

| Iron (Fe) | 424 | 179 |

| Potassium (K) | 90 | 686 |

| Lithium (Li) | 0.77 | 5.60 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 1067 | 1325 |

| Sodium (Na) | 660 | 3372 |

| Ammonia (NH3) | 13.0 | 24.8 |

| Sulphate (SO42−) | 7988 | 4952 |

| pH | 1.13 | 0.07 |

References

- Johnston, D.M.; Daly, M. Auckland erupts!! N. Z. Sci. Mon. 1995, 8, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.; Wilson, T.M.; Deligne, N.I.; Cole, J.W. Volcanic hazard impacts to critical infrastructure: A review. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2014, 286, 148–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blong, R.J. Volcanic Hazards: A Sourcebook on the Effects of Eruptions; Academic Press Inc.: Sydney, Australia, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Guffanti, M.; Mayberry, G.C.; Casadevall, T.J.; Wunderman, R. Volcanic hazards to airports. Nat. Hazards 2009, 51, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.; Daly, M.; Johnston, D. Review of Impacts of Volcanic Ash on Electricity Distribution Systems, Broadcasting and Communication Networks; Technical Publication No. 051; Auckland Engineering Lifelines Group, Auckland Regional Council: Auckland, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Horwell, C.J.; Baxter, P.J.; Hillman, S.E.; Damby, D.E.; Delmelle, P.; Donaldson, K.; Dunster, C.; Calkins, J.A.; Fubini, B.; Hoskuldsson, A.; et al. Respiratory Health Hazard Assessment of Ash from the 2010 Eruption of Eyjafjallajökull Volcano, Iceland: A Summary of Initial Findings from a Multi-Centre Laboratory Study; International Volcanic Health Hazard Network (IVHHN), Durham University: Durham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.M.; Stewart, C.; Cole, J.W.; Dewar, D.J.; Johnston, D.M.; Cronin, S.J. The 1991 Eruption of Volcan Hudson, Chile: Impacts on Agriculture and Rural Communities and Long-Term Recovery; GNS Science Report 2009/66; GNS Science: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2011; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, M.G. Operation of gas turbine engines in an environment contaminated with volcanic ash. J. Turbomach. 2012, 134, 051001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardman, J.; Sword-Daniels, V.; Stewart, C.; Wilson, T. Impact Assessment of the May 2010 Eruption of Pacaya Volcano, Guatemala; GNS Science Report 2012/09; GNS Science: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.M.; Stewart, C.; Sword-Daniels, V.; Leonard, G.S.; Johnston, D.M.; Cole, J.W.; Wardman, J.; Wilson, G.; Barnard, S.T. Volcanic ash impacts to critical infrastructure. Phys. Chem. Earth 2012, 45–46, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.; Horwell, C.; Plumlee, G.; Cronin, S.; Delmelle, P.; Baxter, P.; Calkins, J.; Damby, D.; Mormon, S.; Oppenheimer, C. Protocol for Analysis of Volcanic Ash Samples for Assessment of Hazards from Leachable Elements. Available online: http://www.ivhhn.org/images/pdf/volcanic_ash_leachate_protocols.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- Blake, D.M.; Wilson, T.M.; Gomez, C. Road marking coverage by volcanic ash. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.; Wilson, T.M.; Deligne, N.I.; Cole, J.; Hughes, M. A model to assess tephra clean-up requirements in urban environments. J. Appl. Volcanol. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.M.; Wilson, T.M.; Stewart, C. Visibility in airborne volcanic ash: Considerations for surface transportation using a laboratory-based method. Nat. Hazards. in review.

- Pyle, D.M. The thickness, volume and grainsize of tephra fall deposits. Bull. Volcanol. 1989, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.J. An Analysis of the Seasonal and Short-Term Variation of Road Pavement Skid Resistance. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Warrick, R.A. Four Communities under Ash; Institute of Behavioural Science, University of Colorado: Boulder, CO, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, J.; Blumenthal, E. Evacuate: What an evacuation order given because of a pending volcanic eruption could mean to residents of the Bay of Plenty. Tephra 2004, 21, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, J.W.; Sabel, C.E.; Blumenthal, E.; Finnis, K.; Dantas, A.; Barnard, B.; Johnston, D.M. GIS-based emergency and evacuation planning for volcanic hazards in New Zealand. Bull. N. Z. Soc. Earthq. Eng. 2005, 38, 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.M. Unpublished Field Notes from the Hudson Eruption Field Visit; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nairn, I.A. The Effects of Volcanic Ash Fall (Tephra) on Road and Airport Surfaces; GNS Science Report 2002/13; GNS Science: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2002; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, S. The Vulnerability of New Zealand Lifelines Infrastructure to Ashfall. Ph.D. Thesis, Hazard and Disaster Management, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stammers, S.A.A. The Effects of Major Eruptions of Mt Pinatubo, Philippines and Rabaul Caldera, Papua New Guinea, and the Subsequent Social Disruption and Urban Recovery: Lessons for the Future. Master’s Thesis, University of Canterbury, New Zealand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, M.; Gordon, K.; Johnston, D.; Lorden, R.; Poirot, T.; Scott, J.; Shephard, B. Impacts and Responses to Ashfall in Kagoshima from Sakurajima Volcano—Lessons for New Zealand; GNS Science Report 2001/30; GNS Science: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2001; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, D.M. Physical and Social Impacts of Past and Future Volcanic Eruptions in New Zealand. Ph.D. Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Small Explosion Produces Light Ash Fall at Soufriere Hills Volcano, Montserrat. United States Geological Survey. Available online: https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/ash/ashfall.html#eyewitness (accessed on 20 October 2015).

- Leonard, G.S.; Johnston, D.M.; Williams, S.; Cole, J.W.; Finnis, K.; Barnard, S. Impacts and Management of Recent Volcanic Eruptions in Ecuador: Lessons for New Zealand; GNS Science Report 2005/20; GNS Science: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.M.; Cole, J.; Johnston, D.; Cronin, S.; Stewart, C.; Dantas, A. Short- and long-term evacuation of people and livestock during a volcanic crisis: Lessons from the 1991 eruption of Volcán Hudson, Chile. J. Appl. Volcanol. 2012, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.M. Unpublished Field Notes from the Chaitén Eruption Field Visit; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jamaludin, D. BORDA Respond to Merapi Disaster. Bremen Overseas Research and Development Association, South East Asia, 2010. Available online: http://www.borda-sea.org/news/borda-sea-news/article/borda-respond-to-merapi-disaster.html (accessed on 20 October 2015).

- Wilson, T.; Outes, V.; Stewart, C.; Villarosa, G.; Bickerton, H.; Rovere, E.; Baxter, P. Impacts of the June 2011 Puyehue-Cordón Caulle Volcanic Complex Eruption on Urban Infrastructure, Agriculture and Public Health; GNS Science Report 2012/20; GNS Science: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2013; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T.M. Unpublished Field Notes from the Shinmoedake Eruption Field Visit; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D.M.; Wilson, G.; Stewart, C.; Craig, H.M.; Hayes, J.L.; Jenkins, S.F.; Wilson, T.M.; Horwell, C.J.; Andreastuti, S.; Daniswara, R.; et al. The 2014 Eruption of Kelud Volcano, Indonesia: Impacts on Infrastructure, Utilities, Agriculture and Health; GNS Science Report 2015/15; GNS Science: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2015; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- The Sub-Plinan Eruption of Mt Kelut Volcano on 13 Feb 2014. Volcano Discovery. 2014. Available online: http://www.volcanodiscovery.com/kelut/eruptions/13feb2014plinian-explosion.html (accessed on 31 October 2016).

- Highway Research Board. National Cooperative Highway Research Program Synthesis of Highway Practice 14: Skid Resistance; National Academy of Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dookeeram, V.; Nataadmadja, A.D.; Wilson, D.J.; Black, P.M. The skid resistance performance of different New Zealand aggregate types. In Proceedings of the IPENZ Transportation Group Conference, Shed 6, Wellington, New Zealand, 23–26 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organisation, Regional Aviation Safety Group (Asian and Pacific Region). Industry Best Practices Manual for Timely and Accurate Reporting of Runway Surface Conditions by ATS/AIS to Flight Crew. 2013. Available online: http://www.icao.int/APAC/Documents/edocs/FS-07IBP%20Manual%20on%20Reporting%20of%20Runway%20Surface%20Condition.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2015).

- U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration. Measurement, Construction and Maintenance of Skid-Resistant Airport Pavement Surfaces. Advisory Circular 150/5320-12C. 1997. Available online: http://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/advisory_circular/150-5320-12C/150_5320_12c.PDF (accessed on 3 October 2015).

- Airport Runways: Skid Resistance and Rubber Removal. Blastrac. 2015. Available online: http://pdf.aeroexpo.online/pdf/blastrac/airport-runways-skid-resistance-rubber-removal/168551-3763.html (accessed on 2 August 2017).

- Wilson, D.J.; Chan, W. The Effects of Road Roughness (and Test Speed) on GripTester Measurements; New Zealand Transport Agency Research Report 523; Clearway Consulting Ltd.: Auckland, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Asi, I. Evaluating skid resistance of different asphalt concrete mixes. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Road Association-PIARC. Technical committee report on road surface characteristics, Permanent International Association of Road Congress. In Proceedings of the 18th World Congress, Brussels, Belgium, 13–19 September 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ergun, M.; Iyinam, S.; Iyinam, F. Prediction of road surface friction coefficient using only macro- and microtexture measurements. J. Transp. Eng. 2005, 131, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manual, B.P. Operation Manual of the British Pendulum Skid Resistance Tester; Wessex Engineering Ltd.: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Skid Tester: AG190. Impact Test Equipment Ltd. Available online: http://www.impact-test.co.uk/docs/AG190_HB.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2014).

- Benedetto, J. A decision support system for the safety of airport runways: The case of heavy rainstorms. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2002, 8, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrey, J. Relationships between weather and traffic safety: Past, present and future directions. Climatol. Bull. 1990, 24, 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cova, T.; Conger, S. Transportation hazards. In Transportation Engineers’ Handbook; Kutz, M., Ed.; Centre for Natural and Technological Hazards, University of Utah: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bennis, T.A.; De Wit, L.B. PIARC State-of-the-Art on Friction and IFI. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Australian Runway and Roads Friction Testing Workshop, Sydney, Australia, 5 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, B.N.J.; Tartaglino, U.; Albohr, O. Rubber friction on wet and dry road surfaces: The sealing effect. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 035428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.T.; Cerezo, V.; Zahouani, H. Laboratory test to evaluate the effect of contaminants on road skid resistance. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2014, 228, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Noyce, D.; Lee, C.; Kinar, J.R. Snowstorm event-based crash analysis. Transp. Res. Rec. 2006, 1948, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, A.J.; Knapp, K.K. Interstate highway crash injuries during winter snow and non-snow events. Transp. Res. Board 2001, 1746, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Chung, K.; Ragland, D.R.; Chan, C. Analysis of wet weather related collision concentration locations: Empirical assessment of continuous risk profile. In Proceedings of the 88th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 January 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Aty, M.; Ekram, A.-A.; Huang, H.; Choi, K. A study on crashes related to visibility obstruction due to fog and smoke. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aström, H.; Wallman, C. Friction Measurement Methods and the Correlation between Road Friction and Traffic Safety: A Literature Review; Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute (VTI): Linköping, Sweden, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, T. Pedestrian Slip Resistance Testing: AS/NZS 3661.1:1993; Opus International Consultants Ltd.: Lower Hut, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Aviation Safety Agency. RuFAB—Runway Friction Characteristics Measurement and Aircraft Braking: Volume 3, Functional Friction; Research Project EASA 2008/4; BMT Fleet Technology Limited: Kanata, ON, Canada, 2010; Available online: https://easa.europa.eu/system/files/dfu/Report%20Volume%203%20-%20Functional%20friction.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2015).

- Sarna-Wojcicki, A.M.; Shipley, S.; Waitt, R.B.; Dzurisin, D.; Wood, S.H. Areal distribution, thickness, mass, volume, and grain size of air-fall ash from the six major eruptions of 1980. In The 1980 Eruptions of Mount Saint Helens; USGS Numbered Series 1250; Lipman, P.W., Mullineaux, D.R., Eds.; U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1981; pp. 577–600. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, H.; Okabyashi, T.; Mochihara, M. Influence of eruptions from Mt. Sakurajima on the deterioration of materials. In Proceedings of the Kagoshima International Conference on Volcanoes, Kagoshima, Japan, 19–23 July 1988; pp. 732–735. [Google Scholar]

- Delmelle, P.; Villiéras, F.; Pelletier, M. Surface area, porosity and water adsorption properties of fine volcanic ash particles. Bull. Volcanol. 2005, 67, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiken, G.; Wohletz, K. Volcanic Ash; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wardman, J.B.; Wilson, T.M.; Bodger, P.S.; Cole, J.W.; Johnston, D.M. Investigating the electrical conductivity of volcanic ash and its effect on HV power systems. Phys. Chem. Earth 2012, 45–46, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labadie, J.R. Volcanic Ash Effects and Mitigation. Adapted from a Report Prepared in 1983 for the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency. 1994. Available online: https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/vsc/file_mngr/file-126/Doc%209691_3rd%20ed_Appendix-A.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2017).

- Heiken, G.; Murphy, M.; Hackett, W.; Scott, W. Volcanic Hazards to Energy Infrastructure-Ash Fallout Hazards and Their Mitigation; World Geothermal Congress: Florence, Italy, 1995; pp. 2795–2798. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T.P.; Casadevall, T.J. Volcanic ash hazards to aviation. In Encyclopedia of Volcanoes, 1st ed.; Sigurdsson, H., Houghton, B., Rymer, H., Stix, J., McNutt, S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 915–930. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, K.D.; Cole, J.W.; Rosenberg, M.D.; Johnston, D.M. Effects of volcanic ash on computers and electronic equipment. Nat. Hazards 2005, 34, 231–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Traffic Accident on Slippery Road, iStock Photograph 14892158, Andersen, O., 2010. Available online: http://www.istockphoto.com/photo/van-traffic-accident-on-slippery-road-gm183542417-14892158?st=a141548 (accessed on 1 February 2016).

- Tuck, B.H.; Huskey, L.; Talbot, L. The Economic Consequences of the 1989–1990 Mt. Redoubt Eruptions; Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska: Anchorage, Alaska, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Broom, S.J. Characterisation of “Pseudo-Ash” for Quantitative Testing of Critical Infrastructure Components with a Focus on Roofing Fragility. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.; Wilson, T.; Cole, J.; Oze, C. Vulnerability of laptop computers to volcanic ash and gas. Nat. Hazards 2012, 63, 711–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, T. Skid Resistance Management on the Auckland State Highway Network; Transit New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2005. Available online: http://www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/surface-friction-conference-2005/8/docs/skid-resistance-management-auckland-state-highway-network.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2015).

- Bastow, R.; Webb, M.; Roy, M.; Mitchell, J. An Investigation of the Skid Resistance of Stone Mastic Asphalt Laid on a Rural English County Road Network; Transit New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2004; pp. 1–16. Available online: http://www.nzta.govt.nz/resources/surface-friction-conference-2005/7/docs/investigation-skid-resistance-stone-mastic-asphalt-laid-rural-english-county-road-network.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2015).

- ‘Hidden Menace’ on UK’s Roads. BBC News. 2015. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/file_on_4/4278419.stm (accessed on 12 February 2015).

- Get a Grip: Motorcycle Road Safety. Daily Telegraph. 2008. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/motoring/motorbikes/2750422/Motorcycle-road-safety-Get-a-grip.html (accessed on 12 February 2015).

- NZRF (The New Zealand Roadmarkers Federation Inc.). Road Marking is Road Safety. In Proceedings of the 2005 New Zealand Road Marking Federation Inc. Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand, 17–19 August 2005; Potters Asian Pacific: Dandenong, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- NZRF. NZRF Roadmarking Materials Guide; New Zealand Roadmarkers Federation Inc.: Auckland, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Downer Group. (Christchurch, New Zealand). Personal communication (by email) with roading supervisor. December 2014–January 2015.

- ASTM International. ASTM E303. Standard Test Method for Measuring Surface Frictional Properties Using the British Pendulum Tester; ASTM E303-93 (Reapproved 2013); ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- TNZ (Transit New Zealand). Standard Test Procedure for Measurement of Skid Resistance Using the British Pendulum Tester; Report TNZ T/2:2003; Transit New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, D.J. Filtering out the Ash: Mitigating Volcanic Ash Ingestion for Generator Sets. Master’s Thesis, Hazard and Disaster Management, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM International. ASTM E965. Standard Test Method for Measuring Pavement Macrotexture Depth Using a Volumetric Technique; ASTM E965-96 (Reapproved 2006); ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kagoshima City Office (Kagoshima, Japan). Personal communication (by meeting) with road network and volcanic ash clean-up managers. 8 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Volcano and Country | Year | Ash Thickness (mm) | Observations Related to Skid Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|

| St Helens, United States of America | 1980 | 17 | Ash became slick when wet [17,18,19] |

| Hudson, Chile | 1991 | not specified | Traction problems from ash on road [7,20] |

| Tavurvur and Vulcan, Papua New Guinea | 1994 | 1000 | Vehicles sunk and stuck in deep ash, although passable if hardened [21,22,23] |

| Sakurajima, Japan | 1995 | >1 | Roads slippery [22,24] |

| Ruapehu, New Zealand | 1995–1996 | “thin” | Slippery sludge from ash-rain mix (roads closed) [22,25] |

| Soufrière Hills, United Kingdom (overseas territory) | 1997 | not specified | Rain can turn particles into a slurry of slippery mud [26] |

| Etna, Italy | 2002 | 2–20 | Traction problems, although damp and compacted ash easier to drive on [22] |

| Reventador, Ecuador | 2002 | 2–5 | Vehicles banned due to slippery surfaces [22,27] |

| Chaitén, Chile | 2008 | not specified | Reduced traction caused dam access problems [28,29] |

| Merapi, Indonesia | 2010 | not specified | Slippery roads caused accidents and increased journey times [30] |

| Pacaya, Guatemala | 2010 | 20–30 | Slippery roads with coarse ash [9] |

| Puyehue-Cordón Caulle, Chile | 2011 | >100 | 2WDs experienced traction problems (wet conditions) [31] |

| Shinmoedake, Japan | 2011 | not specified | Ladders very slippery [32] |

| Kelud, Indonesia | 2014 | 1–100 | Roads slippery with increased accident rate [33] |

| Sinabung, Indonesia | 2014 | 80–100 | Road travel impracticable in wet muddy ash [34] |

| Type of Site | Minimum Recommended Skid Resistance Value | Corresponding Coefficient of Friction |

|---|---|---|

| Difficult sites such as: | 65.0 | 0.74 |

| ||

| Motorways and heavily trafficked roads in urban areas (with >2000 vehicles per day) | 55.0 | 0.60 |

| All other sites | 45.0 | 0.47 |

| Type of Site | Typical Skid Resistance Value | Corresponding Coefficient of Friction |

|---|---|---|

| Dry, bare surface | 69.5–82.5 | 0.8–1.0 |

| Wet, bare surface | 62.4–69.5 | 0.7–0.8 |

| Packed snow | 20.6–30.0 | 0.20–0.30 |

| Loose snow/slush | 20.6–47.1 (higher value when tyres in contact with pavement) | 0.20–0.50 |

| Black ice | 15.7–30.0 | 0.15–0.30 |

| Loose snow on black ice | 15.7–25.4 | 0.15–0.25 |

| Wet black ice | 5.4–10.6 | 0.05–0.10 |

| 65 km h−1 | 95 km h−1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maintenance Planning | New Design/Construction | Minimum | Maintenance Planning | New Design/Construction | |

| Mu Meter | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.66 |

| Runway Friction Tester (Dynatest Consulting, Inc.) | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 0.54 | 0.72 |

| Skiddometer (Airport Equipment Co.) | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.82 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.74 |

| Airport Surface Friction Tester | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.82 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.74 |

| Safegate Friction Tester (Airport Technology USA) | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.82 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.74 |

| Griptester Friction Meter (Findlay, Irvine, Ltd.) | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.64 |

| Tatra Friction Tester | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.67 |

| Norsemeter RUNAR (operated at fixed 16% slip) | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.63 |

| Ash Source | Ash Type | Sieve Size (μm) | Soluble Components Added | Sample ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lyttelton Volcanic Group | Hard Basalt | 1000 | No | LYT-BAS1 |

| Yes (RCL) | LYT-BAS2 | |||

| Yes (WICL) | LYT-BAS3 | |||

| 106 | No | LYT-BAS4 | ||

| Punatekahi cone, Taupo | Scoriaceous Basalt | 1000 | No | PUN-BAS1 |

| Yes (RCL) | PUN-BAS2 | |||

| Yes (WICL) | PUN-BAS3 | |||

| Hatepe ash, Taupo | Pumiceous Rhyolite | 1000 | No | HAT-RHY |

| Pupuke, Auckland Volcanic Field | Scoriaceous Basalt | 1000 | No | PUP-BAS1 |

| Yes (WICL) | PUP-BAS3 |

| Asphalt Concrete Slab Condition | Mean Macrotexture Depth (mm) | Ash Surface Coverage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bare, clean and new | 1.37 | 0 |

| Ashed, 10× BPT swings | - | 81 |

| Ashed, 10× BPT swings and brushed (10× strokes) | 0.99 | 40 |

| Cleaned with compressed air | 1.29 | <1 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blake, D.M.; Wilson, T.M.; Cole, J.W.; Deligne, N.I.; Lindsay, J.M. Impact of Volcanic Ash on Road and Airfield Surface Skid Resistance. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081389

Blake DM, Wilson TM, Cole JW, Deligne NI, Lindsay JM. Impact of Volcanic Ash on Road and Airfield Surface Skid Resistance. Sustainability. 2017; 9(8):1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081389

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlake, Daniel M., Thomas M. Wilson, Jim W. Cole, Natalia I. Deligne, and Jan M. Lindsay. 2017. "Impact of Volcanic Ash on Road and Airfield Surface Skid Resistance" Sustainability 9, no. 8: 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081389

APA StyleBlake, D. M., Wilson, T. M., Cole, J. W., Deligne, N. I., & Lindsay, J. M. (2017). Impact of Volcanic Ash on Road and Airfield Surface Skid Resistance. Sustainability, 9(8), 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081389