A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Performance in SMEs in Zambia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. CSR in SMEs

2.2. CSR and Firm Performance in SMEs

2.3. Corporate Social Responsibility Studies in Zambia

2.4. Hypotheses Development

2.4.1. Financial Performance

2.4.2. Corporate Reputation

2.4.3. Employee Commitment

3. Research Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Data Analysis and Results

3.3.1. Convergent Validity

3.3.2. Discriminant Validity

3.3.3. Measurement Invariance Assessment

3.3.4. Model Fit

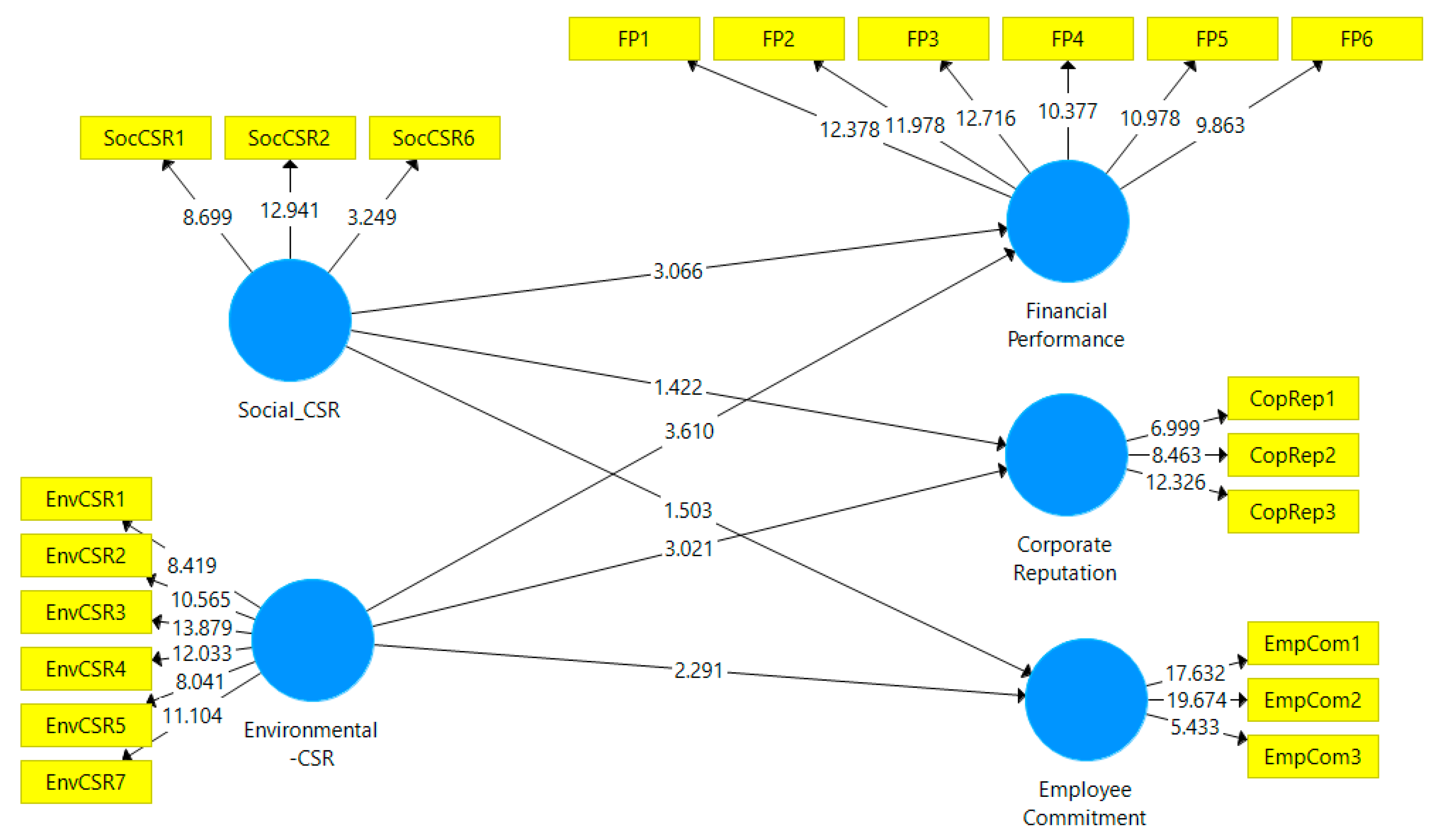

3.3.5. Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Label | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Financial Performance | Relative to our largest competitors, during last year we | |

| FP1 | We had larger market share. | |

| FP2 | We were larger in size. | |

| FP3 | Our profit growth has been substantially better. | |

| FP4 | Our sales growth has been substantially better. | |

| FP5 | Our return on assets has been substantially better. | |

| FP6 | Our return on investment has been substantially better. | |

| Regarding our overall performance, during last year we | ||

| FP7 | Performed poorly relative to competitors | |

| Corporate Reputation | During last five years | |

| CorpRep1 | Our organisation has a good reputation. | |

| CorpRep2 | Our organisation is widely acknowledged as a trustworthy organisation. | |

| CorpRep3 | Our organisation is known to sell high quality products and service. | |

| Employee Commitment | During last five years | |

| EmpCom1 | Our employees are very committed to the organisation. | |

| EmpCom2 | The bond between the organisation and its employees is very strong. | |

| EmpCom3 | Our employees often go above and beyond their regular responsibilities to ensure the organisation’s well-being. | |

| Social-CSR | SocCSR1 | My company ensures workplace health and safety |

| SocCSR2 | My company implements training and development programs for employees | |

| SocCSR3 | My company periodically tests employee satisfaction | |

| SocCSR4 | My company human resource policy is partially aimed at workplace diversity | |

| SocCSR5 | My company sponsors students in schools | |

| SocCSR6 | My company offers industrial attachments (internships) to students | |

| SocCSR7 | My company uses a formal customer complaints register for clients | |

| SocCSR8 | My company is active within an organisation with a social purpose | |

| Environmental-CSR | EnvCSR1 | My company saves energy beyond legal requirements |

| EnvCSR2 | My company saves water beyond legal requirements | |

| EnvCSR3 | My company voluntarily does recycling and/or re-use | |

| EnvCSR4 | My company takes action in order to reduce waste | |

| EnvCSR5 | My company purchases environmentally friendly products | |

| EnvCSR6 | My company is a member of an environmental organisation | |

| EnvCSR7 | My company is well equipped in order to improve the sustainability/CSR of my clients | |

| EnvCSR8 | My company suggests sustainable solutions to our clients |

References

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurel, E. Social and ecological engagement and economic firm performance: Correlated or not? CSR evidence from SMEs in two Dutch retail sectors. In Proceedings of the Conference of Growing Sustainable Business, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands, 17 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance in Indian companies? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettab, B.; Brik, A.B.; Mellahi, K. A Study of Management Perceptions of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organisational Performance in Emerging Economies: The Case of Dubai. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.; Spence, L. Editorial: Responsibility and small business. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, L.C. Corporate social responsibility and SMEs: A literature review and agenda for future research. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2011, 9, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kechiche, A.; Soparnot, R. CSR within SMEs: Literature review. Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, J.; Laroche, P. A meta-analytical investigation of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Rev. Gest. Ressour. Hum. 2005, 57, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable Development and Entrepreneurship: Past Contributions and Future Directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Ahlstrom, D.; Obloj, K. Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies: Where Are We Today and Where Should the Research Go in the Future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K.; Adegbite, E.; Ogbechie, C.; Idemudia, U.; Kan, K.A.S.; Issa, M.; Anakwue, O.I.J. Corporate Social Responsibility in SMEs: A Shift from Philanthropy to Institutional Works? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 138, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idemudia, U. Corporate social responsibility and developing countries: Moving the critical CSR research agenda in Africa forward. Progress Dev. Stud. 2011, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Lund-Thomsen, P.; Jeppesen, S. SMEs and CSR in Developing Countries. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, E.; Stanila, G.O.; Brad, L. The influence of environmental and social performance on financial performance: Evidence from Romania’s listed entities. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2513–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-S.; Chang, R.-Y.; Dang, V.T. An integrated model to explain how corporate social responsibility affects corporate financial performance. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8292–8311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Sha, J.; Zhang, H.; Ke, W. Relationship between corporate social responsibility and financial performance in the mineral Industry: Evidence from Chinese mineral firms. Sustainability 2014, 6, 4077–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurel, E.; Rens, J. How Is CSR-Intensity Related to the Entrepreneur’s Motivation to Engage in CSR? Empirical Evidence from Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in the Dutch Construction Sector. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2015, 13, 333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Choongo, P.; van Burg, E.; Masurel, E.; Paas, L.J.; Lungu, J. Corporate Social Responsibility Motivations in Zambian SMEs. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2017, 15, 29–62. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, M.; Salanta, I. Corporate social responsibility versus corporate social irresponsibility. Manag. Mark. 2014, 9, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Sustainability: The Concept of Modern society in Idowu & Schmidpeter (Eds), Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability, Ethics and Governance; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlsrud, A. How Corporate Social Responsibility is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J.; Rutherfoord, R. Small business and empirical perspectives in business ethics: Editorial. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 47, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuijnck, G.; Ngnodjom, H. Responsibility and Informal CSR in Formal Cameroonian SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Small Business Champions for Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Schaefer, A. Small and medium sized enterprises and sustainability: Managers’ values and engagement with environmental and climate change issues. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.B.; Manring, S.L. Strategy development in small and medium sized enterprises for sustainability and increased value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revell, A.; Stokes, D.; Chen, H. Small Business and the Environment: Turning Over the Leaf? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Masurel, E. Why SMEs Invest in Environmental Measures: Sustainability Evidence from Small and Medium-Sized Printing Firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M.; Gherib, J.B.B.; Biwole, V.O. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Is Entrepreneurship will Enough? A North-South Comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 335–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.A.P.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Environmental Management, Climate Change, CSR, and Governance in Clusters of Small Firms in Developing Countries Toward an Integrated Analytical Framework. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W.; McIntosh, M.; Middleton, C. Corporate Citizenship in Africa; Greenleaf: Sheffield, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turyakira, P.; Venter, E.; Smith, E. The impact of corporate social responsibility factors on the the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2014, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K.M.; Adi, B.C.; Ogbechie, C.; Amao, O.O. Corporate Social Responsibility in Nigeria: Western Mimicry or Indigenous Influences? J. Corp. Citizensh. 2006, 24, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, J.; Shikwe, A. Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in Small-Scale Mining on the Copperbelt; Mission Press: Ndola, Zambia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muthuri, J.N.; Gilbert, V. An Institutional Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility in Kenya. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilman, H.; Gorondutse, A.H. Relationship between perceived ethics and Trust of Business Social Responsibility (BSR) on performance of SMEs in Nigeria. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 15, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- World Business Council for Sustainable-Development. Corporate Social Responsibility: Meeting Changing Expectations; World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- World Business Council for Sustainable-Development. Corporate Social Responsibility: Making Good Business Sense; World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed, W.S.W.; Almsafir, M.K.; Al-Smadi, A.W. Does corporate social responsibility lead to improve in firm financial performance? Evidence from malaysia. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2014, 6, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Torugsa, N.A.; O’Donohue, W.; Hecker, R. Capabilities, proactive CSR and financial performance in SMEs: Empirical evidence from an Australian manufacturing industry sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.J.; Higgins, M.M.; Rhee, G.S. Stock Market Reaction to Ethical Initiatives of Defense Contractors: Theory and Evidence. Crit. Perspect. Account. 1997, 8, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; Ferris, S.P. Agency Conflict and Corporate Strategy: The Effect of Divestment on Corporate Value. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dobers, P.; Halme, M. Corporate social responsibility and developing countries. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J.; Painter-Morland, M. Ethics in Small and Medium Sized Enterprises. A Global Commentary; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, A.; Lungu, J. For Whom The Windfalls? Winners & Losers in the Privatisation of Zambia’s Copper Mines: Printex, Lusaka, Zambia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lungu, J.; Kapena, S. South African Mining Companies Corporate Governance Practices in Zambia: The Case of Chibuluma Mine; Southern Africa Resource: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010; pp. 47–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lungu, J.; Mulenga, C. Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in the Extractive Industry in Zambia; Mission Press: Ndola, Zambia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mayondi, W. Mining and Corporate Social Responsibility in Zambia: A Case Study of Barrick Gold Mine. Masters’ Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Choongo, P.; Van Burg, E.; Paas, L.J.; Masurel, E. Factors Influencing the Identification of Sustainable Opportunities by SMEs: Empirical Evidence from Zambia. Sustainability 2016, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A. Recognising Opportunities for Sustainable Development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Herold, D.M.; Yu, A.-L. Small and Medium Enterprises and Corporate Social Responsibility Practice: A Swedish Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 23, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankelow, G.; Quazi, A. Factors affecting SMEs Motivations for Corporate Social Responsibility, in Australan and New Zeland Marketing Academy. Conf. Track 2007, 5, 2367–2374. [Google Scholar]

- Graafland, J.; Mazereeuw-Van der Duijn Schouten, C. Motives for Corporate Social Responsibility. De Econ. 2012, 160, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Jermier, J.M.; Lafferty, B.A. Corporate reputation: The definitional landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowduri, S. Framework for Sustainability Entrepreneurship for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in an Emerging Economy. World J. Manag. 2012, 4, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah, A. Corporate reputation: The boardroom challenge. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2003, 3, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, M.; Schwaiger, M. Corporate reputation: Disentangling the effects on financial performance. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj-Andrés, E.; López-Pérez, M.E.; Melero-Polo, I.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R. Company image and corporate social responsibility: Reflecting with SMEs’ managers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Zanhour, M.; Keshishian, T. Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in the context of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Reputation and Institutional Investors. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munasinghe, M.; Malkumari, A. Corporate social responsibility in small and medium enterprises (SME) in Sri Lanka. J. Emerg. Trends Econ. Manag. Sci. 2012, 3, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Nijhof, W.J.; Jong, M.J.D.; Beukhof, G. Employee commitment in changing organizations: An exploration. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1998, 22, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintayo, D. Work-family role conflict and organizational commitment among industrial workers in Nigeria. Int. J. Psychol. Couns. 2010, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ongori, H. A review of the literature on employee turnover. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2007, 1, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Vance, R.J. Employee Engagement and Commitment. SHRM Found. 2006. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/foundation/ourwork/initiatives/resources-from-past-initiatives/Documents/Employee%20Engagement%20and%20Commitment.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Ali, I.; Rehman, K.U.; Ali, S.I.; Yousaf, J.; Zia, M. Corporate social responsibility influences, employee commitment and organizational performance. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2796–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Albinger, H.S.; Freeman, S.J. Corporate social performance and attractiveness as an employer to different job seeking populations. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 28, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, A. Social and Environmental Responsibility in Small and Medium Enterprises in Latin America; Inter-American Bank, Sustainable Department: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, K.L.; Donthu, N.; Kennett, P.A. A longitudinal analysis of satisfaction and profitability. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 47, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Cohen, J.F. A longitudinal Study of Trust and Perceived Usefulness in Consumer Acceptance of an eService: the Case of Online Health Services; PACIS: Langkawi, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kriauciunas, A.; Parmigiani, A.; Rivera-Santos, M. Leaving our comfort zone: Intergrating established practices with uniques adaptations to conduct survey-based strategy research in nontraditional contexts. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 994–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Robinson, R.B. Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.G. Measuring performance of small-and-medium sized enterprises: The grounded theory approach. J. Bus. Public Aff. 2008, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- De Massis, A.; Kotlar, J.; Campopiano, G.; Cassia, L. The impact of family involvement on SMEs’ performance: Theory and evidence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 924–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonial, S.C.; Carter, R.E. The Impact of Organizational Orientations on Medium and Small Firm Performance: A Resource-Based Perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronum, S.; Verreynne, M.L.; Kastelle, T. The role of networks in small and medium-sized enterprise innovation and firm performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2012, 50, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, P.D. The Balanced Scorecard—Measures That Drive Performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1992, 70, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ismail Salaheldin, S. Critical success factors for TQM implementation and their impact on performance of SMEs. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2009, 58, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Ng, H.P. The effects of entrepreneurial orientation and marketing information on the performance of SMEs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herche, J.; Engelland, B. Reversed-polarity items and scale unidimensionality. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1996, 24, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows (Versions 10 and 11): SPSS Student Version 11.0 for Windows; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Sever, J.M. The Reputation QuotientSM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. J. Brand Manag. 2000, 7, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: An Investigation in the U.K. Supermarket Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 34, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, J.C.; Moreno, A.M. The relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and growth: The moderating role of family involvement. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaura, S.; Carter, S. Does Entrepreneurship Make You Wealthy? Enterprise Research Centre: Birmingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Juslin, H. Values and corporate social responsibility perceptions of Chinese University Students. J. Acad. Ethics 2012, 10, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, R.Z. An examination of business students’ perception of corporate social responsibilities before and after bankruptcies. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 52, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, S.; Richard, O.C.; Chadwick, K. Gender diversity in management and firm performance: The influence of growth orientation and organizational culture. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 6 June 2017).

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, F.J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Lance, C.E. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 2000, 3, 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F. Entrepreneurial orientation in hotel industry: Multi-group analysis of quality certification. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4714–4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; D’Ambra, J.; Ray, P. An evaluation of PLS based complex models: The roles of power analysis, predictive relevance and GoF index. In Proceedings of the 17th Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS2011), Detroit, AL, USA, 4–7 August 2011; Available online: http://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/3126 (accessed on 13 July 2017).

- Garson, G.D. Partial Least Squares: Regression and Structural Equation Models; Statistical Publishing Associates: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Items | Loadings | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Reputation | CopRep1 | 0.837 | 0.913 | 0.777 |

| CopRep2 | 0.902 | |||

| CopRep3 | 0.905 | |||

| Employee Commitment | EmpCom1 | 0.891 | 0.870 | 0.693 |

| EmpCom2 | 0.890 | |||

| EmpCom3 | 0.702 | |||

| Environmental-CSR | EnvCSR1 | 0.741 | 0.869 | 0.527 |

| EnvCSR2 | 0.793 | |||

| EnvCSR3 | 0.717 | |||

| EnvCSR4 | 0.750 | |||

| EnvCSR5 | 0.676 | |||

| EnvCSR7 | 0.669 | |||

| Financial Performance | FP1 | 0.761 | 0.899 | 0.598 |

| FP2 | 0.768 | |||

| FP3 | 0.809 | |||

| FP4 | 0.782 | |||

| FP5 | 0.780 | |||

| FP6 | 0.737 | |||

| Social-CSR | SocCSR1 | 0.826 | 0.765 | 0.529 |

| SocCSR2 | 0.800 | |||

| SocCSR6 | 0.515 |

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Corporate Reputation | 0.882 | ||||

| 2 | Employee Commitment | 0.394 | 0.833 | |||

| 3 | Environmental-CSR | 0.319 | 0.304 | 0.726 | ||

| 4 | Financial Performance | 0.218 | 0.246 | 0.391 | 0.773 | |

| 5 | Social-CSR | 0.239 | 0.255 | 0.336 | 0.364 | 0.728 |

| Composite | c-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Compositional Invariance? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Reputation | 0.9992 | [1.0000; 1.0000] | Yes |

| Employee Commitment | 0.9977 | [0.9999; 1.0000] | Yes |

| Environmental-CSR | 0.9907 | [0.9988; 1.0000] | Yes |

| Financial Performance | 0.9926 | [0.9995; 1.0000] | Yes |

| Social-CSR | 0.9771 | [0.9989; 1.0000] | Yes |

| Composite Difference of the composites’ mean value | 95% confidence interval | Equal mean values? | |

| Corporate Reputation | −0.001 | [−0.007; 0.007] | Yes |

| Employee Commitment | 0.001 | [0.001; −0.006] | Yes |

| Environmental-CSR | −0.001 | [−0.001; −0.008] | Yes |

| Financial Performance | 0.000 | [−0.006; 0.008] | Yes |

| Social-CSR | 0.002 | [−0.004; 0.008] | Yes |

| Composite Difference of the composites’ variance ratio (=0) | 95% confidence interval | Equal variance? | |

| Corporate Reputation | 0.001 | [−0.011; 0.012] | Yes |

| Employee Commitment | −0.003 | [0.001; 0.011] | Yes |

| Environmental-CSR | −0.004 | [−0.017; 0.009] | Yes |

| Financial Performance | 0.000 | [−0.010; 0.012] | Yes |

| Social-CSR | −0.001 | [−0.019; 0.007] | Yes |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficient | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2b | Environmental-CSR → Corporate Reputation | 0.269 | 0.286 | 0.089 | 3.021 | 0.003 ** | Supported |

| H3b | Environmental-CSR → Employee Commitment | 0.246 | 0.269 | 0.108 | 2.291 | 0.022 ** | Supported |

| H1b | Environmental-CSR → Financial Performance | 0.303 | 0.323 | 0.084 | 3.610 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H2a | Social-CSR → Corporate Reputation | 0.149 | 0.147 | 0.104 | 1.422 | 0.156 | Rejected |

| H3a | Social-CSR → Employee Commitment | 0.172 | 0.164 | 0.114 | 1.503 | 0.133 | Rejected |

| H1a | Social-CSR → Financial Performance | 0.262 | 0.261 | 0.085 | 3.066 | 0.002 ** | Supported |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choongo, P. A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Performance in SMEs in Zambia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081300

Choongo P. A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Performance in SMEs in Zambia. Sustainability. 2017; 9(8):1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081300

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoongo, Progress. 2017. "A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Performance in SMEs in Zambia" Sustainability 9, no. 8: 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081300

APA StyleChoongo, P. (2017). A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Performance in SMEs in Zambia. Sustainability, 9(8), 1300. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081300