Hidden Roles of CSR: Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility as a Preventive against Counterproductive Work Behaviors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

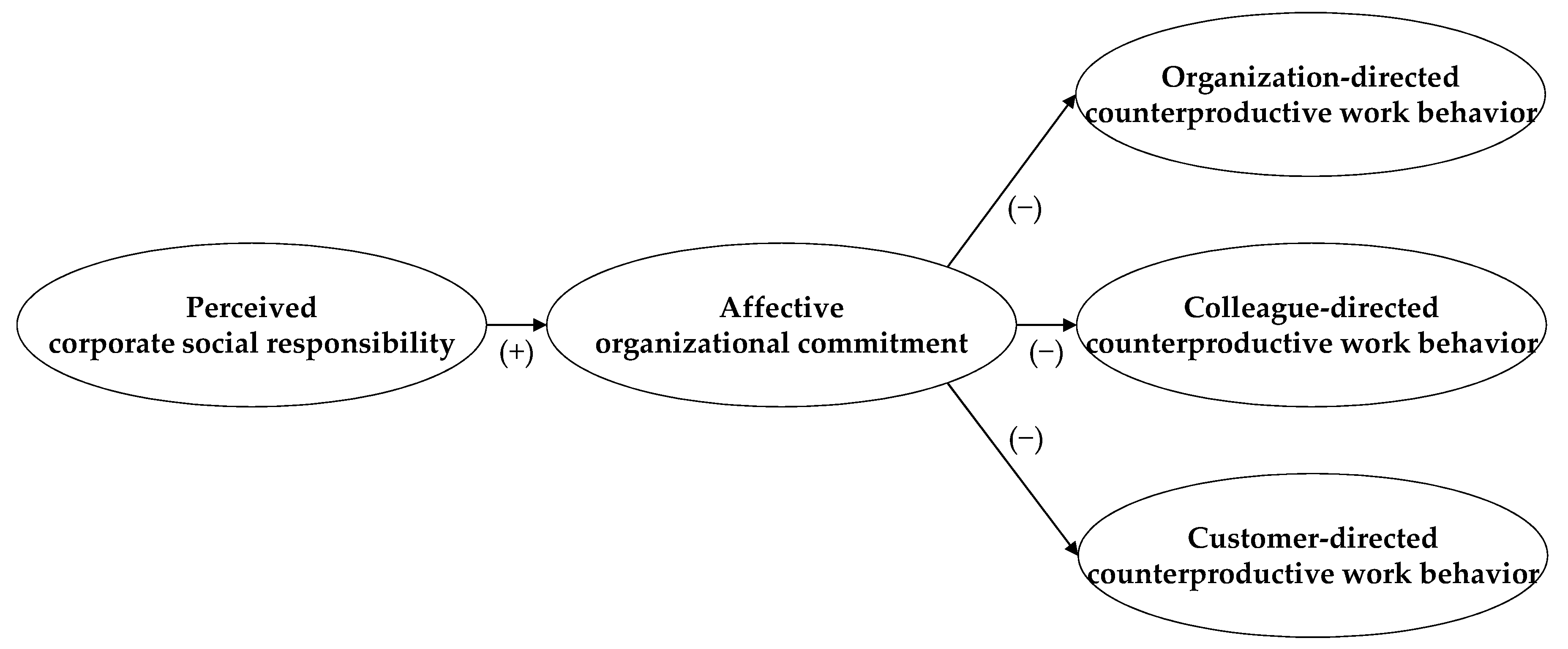

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling Procedures and Participant Characteristics

3.2. Measurement Scales

4. Results

4.1. Reliability, Validity, and Common Method Bias

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Study Directions

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chappell, D.; Di Martino, V. Violence at Work; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S. An emotion-centered model of voluntary work behavior: Some parallels between counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.; Pinedo, M. Total quality management and operational risk in the service industries. In Tutorials in Operations Research: State-of-the-Art Decision-Making Tools in the Information-Intensive Age; Chen, Z.-L., Raghavan, S., Eds.; INFORMS: Hanover, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Jobst, A.A. The treatment of operational risk under the New Basel framework: Critical issues. J. Bank. Regul. 2007, 8, 316–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.J.; Robinson, S.L. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, R.S. A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, S.; Spector, P.E.; Miles, D. Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 59, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.M.; Penney, L.M. The waiter spit in my soup! Antecedents of customer-directed counterproductive work behavior. Hum. Perform. 2014, 27, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, L.M.; Spector, P.E. Job stress, incivility, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The moderating role of negative affectivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, C.W.; Skitka, L.J. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Yu, Y. The influence of perceived corporate sustainability practices on employees and organizational performance. Sustainability 2014, 6, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.W.; Hur, W.M.; Ko, S.H.; Kim, J.W.; Yoon, S.W. Bridging corporate social responsibility and compassion at work: Relations to organizational justice and affective organizational commitment. Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Gilat, G.; Waldman, D.A. The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Hur, W.M.; Kang, S. Employees’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility and job performance: A sequential mediation model. Sustainability 2016, 8, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J. Current directions in mediation analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Yin, H.; Liu, J.; Lai, K. How is employee perception of organizational efforts in corporate social responsibility related to their satisfaction and loyalty toward developing harmonious society in Chinese enterprises? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of group behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Tajfel, H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.J.; Wokutch, R.E.; Harringto, K.V.; Dennis, B.S. An examination of the influence of diversity and stakeholder role on corporate social orientation. Bus. Soc. 2001, 40, 266–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. The effect of stakeholder preferences, organizational structure and industry type on corporate community involvement. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 45, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.; Rogovsky, N.; Dunfree, T.W. The next wave of corporate community involvement: Corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 44, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollinger, R.C. Acts against the workplace: Social bonding and employee deviance. Deviant Behav. 1986, 7, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, T. Causes of Delinquency; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, R.L. Ethical rule breaking by employees: A test of social bonding theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 40, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.; Meyer, J.P.; Lee, K.; Shin, K.H.; Yoon, C.Y. Affective and continuance commitment and their relations with deviant workplace behaviors in Korea. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2011, 28, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Joshi, A.; Chuang, A. Sticking out like a sore thumb: Employee dissimilarity and deviance at work. Pers. Psychol. 2004, 57, 969–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korschun, D.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Swain, S.D. Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrasqueiro, Z.; Nunes, P.M. Financing behaviour of Portuguese SMEs in hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 43, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.J.G.; Cruz, Y.D.M.A. Relation between social-environmental responsibility and performance in hotel firms. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Jang, J.H. The role of gender differences in the impact of CSR perceptions on corporate marketing outcomes. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.; Grace, D.; Funk, D.C. Employee brand equity: Scale development and validation. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 19, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Zhu, W.; Koh, W.; Bhatia, P. Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.N.; Rutherford, B.N.; Feinberg, R.; Anderson, J.G. Antecedents of mentoring: Do multi-faceted job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment matter? J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2039–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Transformational leadership, organizational clan culture, organizational affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior: A case of South Korea’s public sector. Public Organ. Rev. 2014, 14, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Methods; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Insrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.S.; Tashchian, A.; Shore, T.H. Codes of ethics as signals for ethical behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | λ | α | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived CSR | Perceived CSR1 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| Perceived CSR2 | 0.90 | |||

| Perceived CSR3 | 0.89 | |||

| AOC | AOC1 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| AOC2 | 0.73 | |||

| AOC3 | 0.82 | |||

| AOC4 | 0.78 | |||

| CWB-O | CWB-O1 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.93 |

| CWB-O2 | 0.82 | |||

| CWB-O3 | 0.77 | |||

| CWB-O4 | 0.85 | |||

| CWB-O5 | 0.90 | |||

| CWB-I | CWB-I1 | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.86 |

| CWB-I2 | 0.67 | |||

| CWB-I3 | 0.86 | |||

| CWB-I4 | 0.78 | |||

| CWB-C | CWB-C1 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| CWB-C2 | 0.81 | |||

| CWB-C3 | 0.91 | |||

| CWB-C4 | 0.89 | |||

| CWB-C5 | 0.84 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.45 | 0.50 | - | |||||||

| 2. Age | 30.43 | 6.80 | 0.50 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. Work experience | 6.04 | 5.58 | 0.31 ** | 0.84 ** | - | |||||

| 4. Perceived CSR | 3.64 | 0.80 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.72 | ||||

| 5. AOC | 3.58 | 0.74 | 0.20 ** | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.54 ** | 0.58 | |||

| 6. CWB-O | 1.27 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.09 | −0.21 ** | 0.72 | ||

| 7. CWB-I | 1.53 | 0.63 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.14 * | −0.14 * | −0.20 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.60 | |

| 8. CWB-C | 1.48 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.18 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.74 |

| From → To | AOC | CWB-O | CWB-I | CWB-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.13 | 0.17 * | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| Age | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| Work experience | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Perceived CSR | 0.57 ** | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.00 |

| AOC | −0.26 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.32 ** | |

| Effects | b | CIlow | CIhigh | |

| Total Effect (perceived CSR → CWB-O) | −0.073 | −0.182 | 0.035 | |

| Indirect Effect (perceived CSR → AOC → CWB-O) | −0.147 * | −0.292 | −0.057 | |

| Direct Effect (perceived CSR → CWB-O) | 0.074 | −0.051 | 0.260 | |

| Total Effect (perceived CSR → CWB-O) | −0.146 * | −0.261 | −0.033 | |

| Indirect Effect (perceived CSR → AOC → CWB-O) | −0.118 * | −0.250 | −0.024 | |

| Direct Effect (perceived CSR → CWB-O) | −0.029 | −0.179 | 0.144 | |

| Total Effect (perceived CSR → CWB-O) | −0.188 * | −0.322 | −0.060 | |

| Indirect Effect (perceived CSR → AOC → CWB-O) | −0.185 * | −0.344 | −0.076 | |

| Direct Effect (perceived CSR → CWB-O) | −0.002 | −0.173 | 0.193 | |

| R2 | ||||

| AOC | 39.0% | |||

| CWB-O | 8.2% | |||

| CWB-I | 9.2% | |||

| CWB-C | 10.1% | |||

| Model Fit Index: χ2(227) = 480.55; RMSEA = 0.07; SRMR = 0.07; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.92 | ||||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, I.; Hur, W.-M.; Kim, M.; Kang, S. Hidden Roles of CSR: Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility as a Preventive against Counterproductive Work Behaviors. Sustainability 2017, 9, 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060955

Shin I, Hur W-M, Kim M, Kang S. Hidden Roles of CSR: Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility as a Preventive against Counterproductive Work Behaviors. Sustainability. 2017; 9(6):955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060955

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Inyong, Won-Moo Hur, Minsung Kim, and Seongho Kang. 2017. "Hidden Roles of CSR: Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility as a Preventive against Counterproductive Work Behaviors" Sustainability 9, no. 6: 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060955

APA StyleShin, I., Hur, W.-M., Kim, M., & Kang, S. (2017). Hidden Roles of CSR: Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility as a Preventive against Counterproductive Work Behaviors. Sustainability, 9(6), 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060955