Screening Indicators for the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

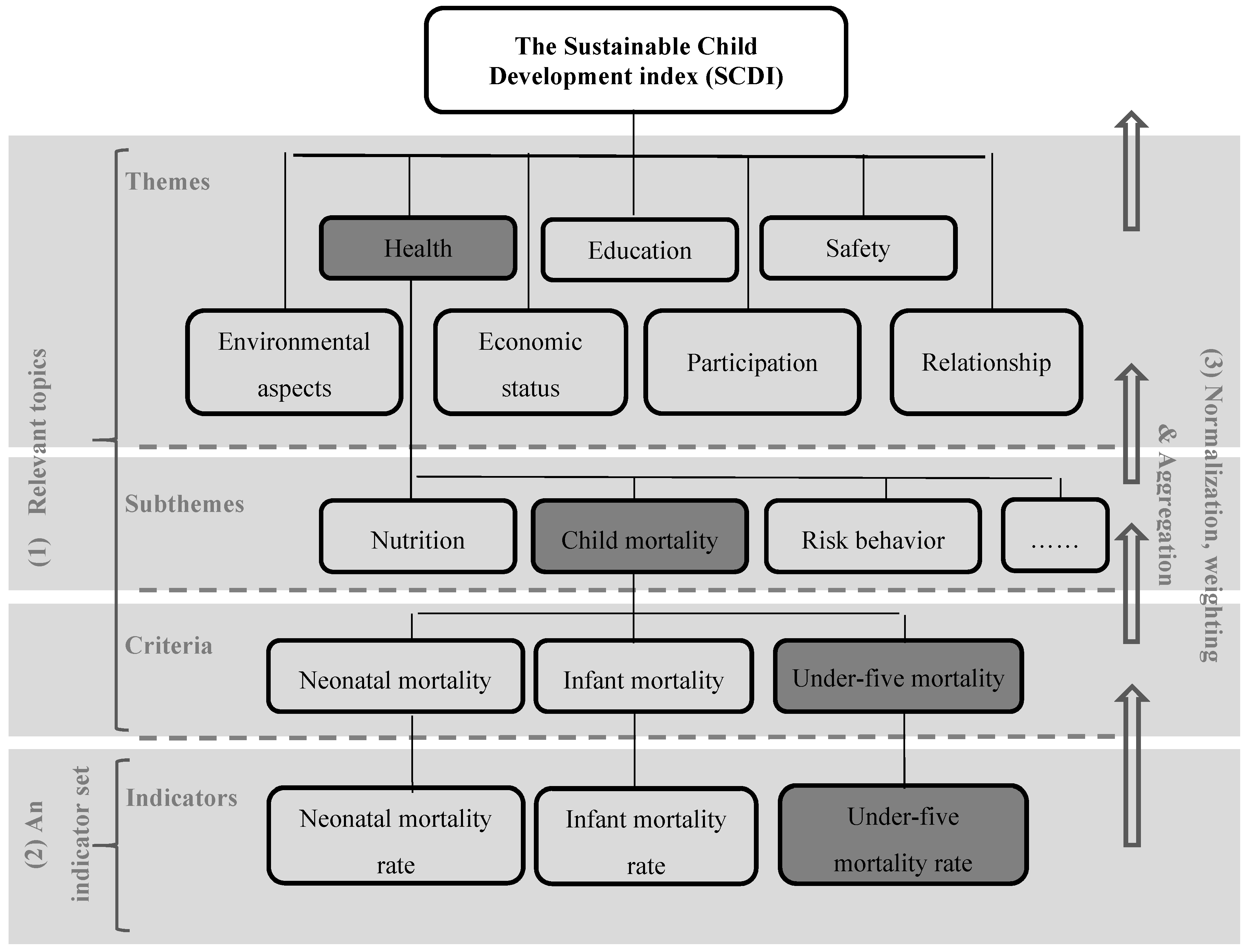

1.1. The SCDI Framework and Potential Application

1.2. Research Objective

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

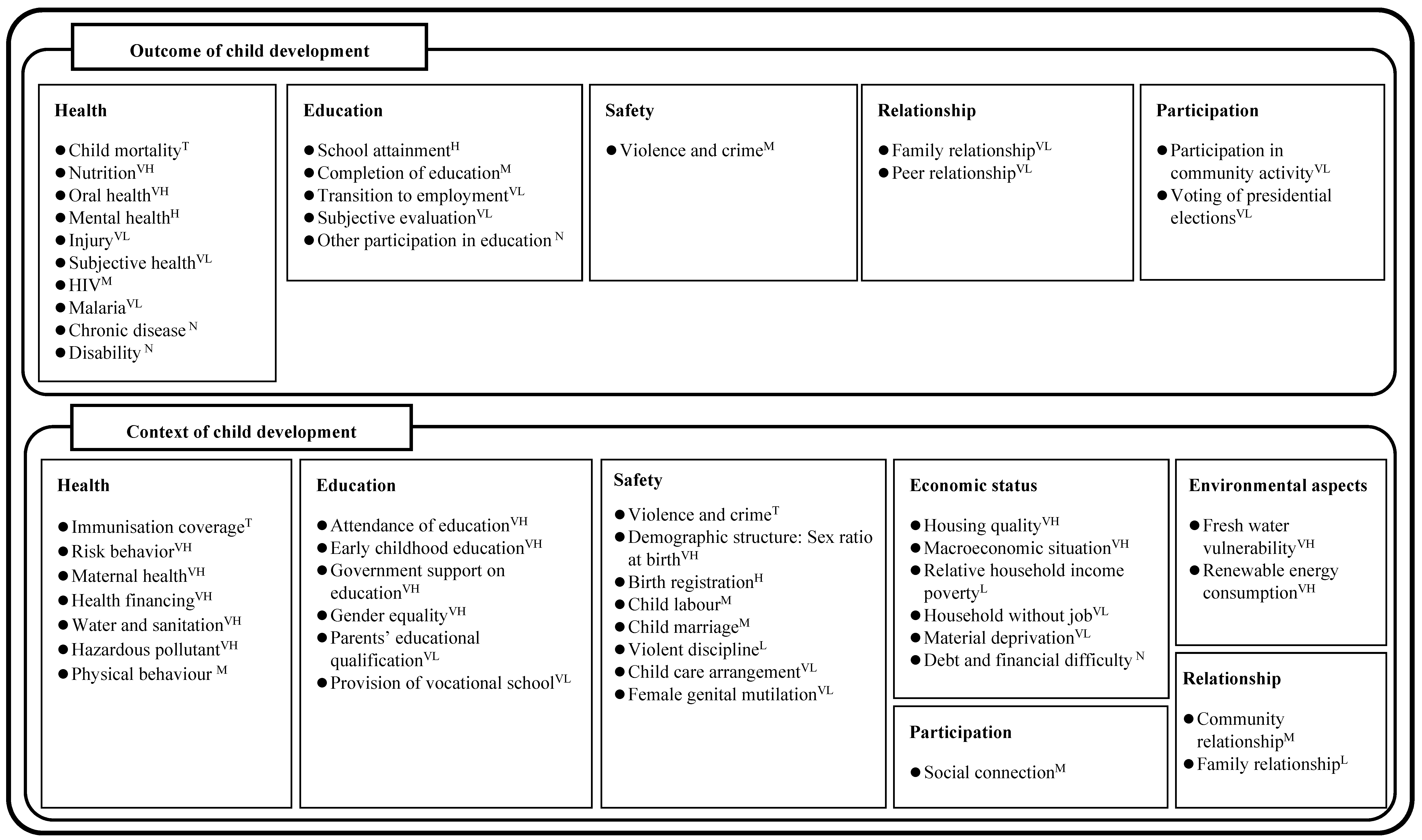

3.1. Selection of the Initial Indicator Set

3.2. Analysis of Indicators for the SCDI

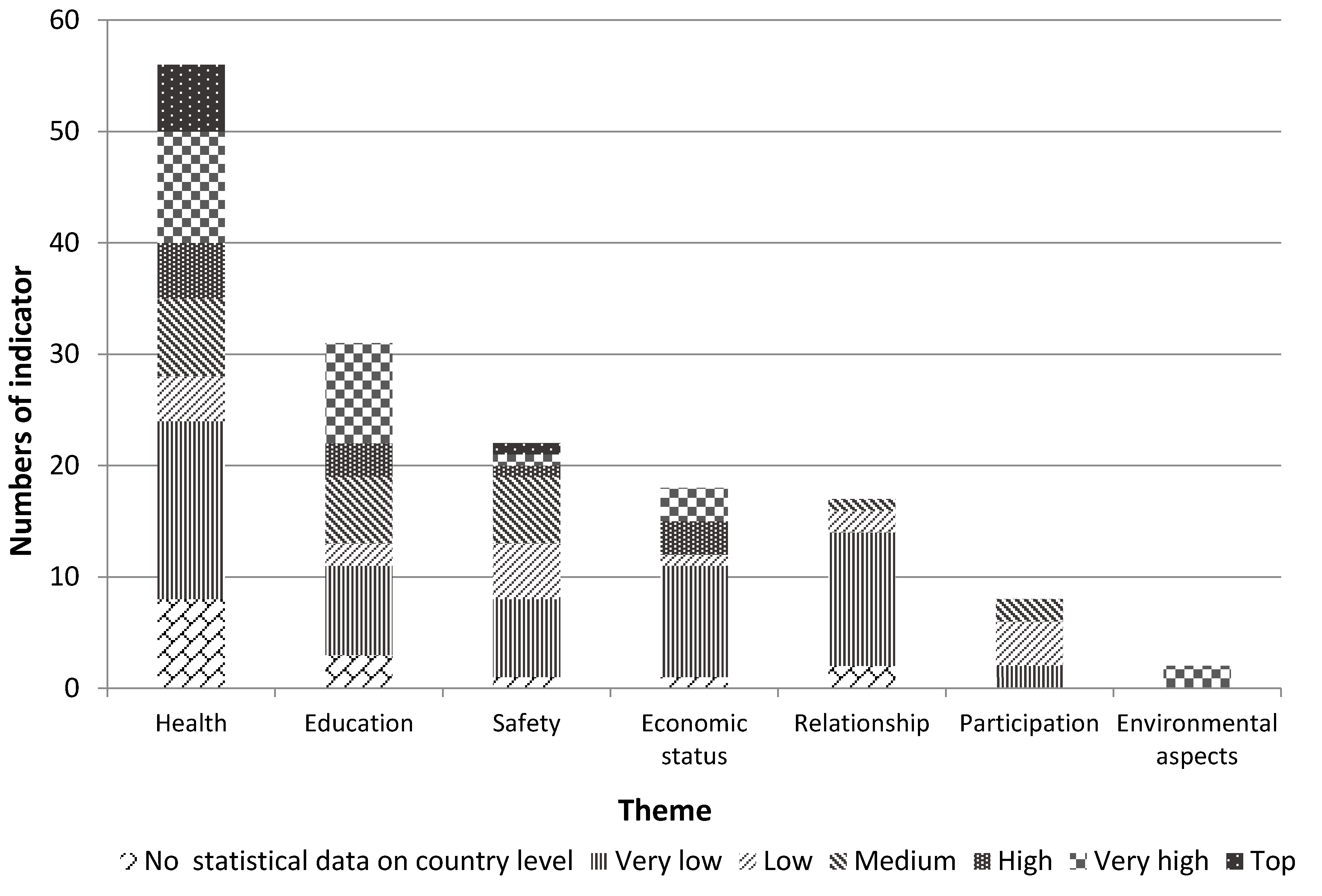

- The data availability of indicators differs among the different topics, for example data availability for the theme health is high, but for the theme relationship is low.

- The share of indicators differs for the different topics of the SCDI framework, for instance most indicators are available for the theme health.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resource. World Conservation Strategy—Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development; International Union for Conservation of Nature Resource: Gland, Switzerland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). A Post-2015 World Fit for Children—Sustainable Development Starts and Ends with Safe, Healthy and Well-Educated Children; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halleröd, B.; Rothstein, B.; Daoud, A.; Nandy, S. Bad governance and poor children: A comparative analysis of government efficiency and severe child deprivation in 68 low- and middle-income countries. World Dev. 2013, 48, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arieh, A.; Casas, F.; Frønes, I.; Korbin, J.E. The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, A. From Child Welfare to Children Well-Being: The Child Indicators Perspective. In From Child Welfare to Child Well-Being—An International Perspective on Knowledge in the Service of Policy Making; Kamerman, S.B., Phipps, S., Ben-Arieh, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, A. The child indicators movement: Past, present, and future. Child Indic. Res. 2008, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Save the Children Fund. The Child Development Index—Holding Governments to Account Children’s Wellbeing; The Save the Children Fund: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The Save the Children Fund. The Child Development Index 2012—Progress, Challenges and Inequality; The Save the Children Fund: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). Human Development Report 2014; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Society. The Good Childhood Report 2013; Children’s Society: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation for Child Development. Child and Youth Well-Being Index (CWI); Foundation for Child Development: New York, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). An Overview of Child Well-Being in Rich Countries; UNICEF: Florence, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, J.; Hoelscher, P.; Richardson, D. An Index of Child Well-being in the European Union. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 80, 133–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Annie E Casey Foundation. The New KIDS COUNT Index; The Annie E Casey Foundation: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-J.; Schneider, L.; Finkbeiner, M. Assessing Child Development: A Critical Review and the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI). Sustainability 2015, 7, 4973–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Murty, H.R.; Gupta, S.K.; Dikshit, A.K. An overview of sustainability assessment methodologies. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 15, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciegis, R.; Ramanauskiene, J.; Startiene, G. Theoretical reasoning of the use of indicators and indices for sustainable development assessment. Eng. Econ. 2009, 63, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs (accessed on 17 June 2016).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2016; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, L.; Mendes, A.; Teixeira, A.A.C. A review essay on the measurement of child well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 106, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being 2013; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Land, K.C.; Lamb, V.L.; Meadows, S. Conceptual and Methodological Foundations of the Child and Youth Well-Being Index. In The Well-Being of America’s Children—Developing and Improving the Child and Youth Well-Being Index; Land, K.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Land, K.C.; Lamb, V.L.; Meadows, S.; Zheng, H.; Fu, Q. The CWI and Its Components: Empirical Studies and Findings. In The Well-Being of America’s Children—Developing and Improving the Child and Youth Well-Being Index; Land, K.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 29–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.J. Mapping Domains and Indicators of Children’s Well-Being. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2797–2805. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion. Measuring the Health of Infants, Children and Youth for Public Health in Ontario: Indicators, Gaps and Recommendations for Moving Forward; Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, L. A Child Health Index for the North-Eastern Parts of Göteborg; Nordic School of Public Health: Göteborg, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A.; Mbwana, K.; Theokas, C.; Lippman, L.; Bloch, M.; Vandivere, S.; O’Hare, W. Child Well-Being: An Index Based on Data of Individual Children; Child Trends.: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.J.; Kim, S.S.; Ahn, J.J.; Yoo, J.P. Developing an index of child well-being in Korea. In Proceedings of the 4th International Society of Child Indicators Conference, Seoul, Korea, 11–15 February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Niclasen, B.; Köhler, L. National indicators of child health and well-being in Greenland. Scand. J. Public Health 2009, 37, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.Y.-N. A clustering approach to comparing children’s wellbeing accross countries. Child Indic. Res. 2014, 7, 553–567. [Google Scholar]

- Erbstein, N.; Hartzog, C.; Geraghty, E.M. Putting youth on the map: A pilot instrument for assessing youth well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2013, 6, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanafin, S.; Brooks, A.-M.; Carroll, E.; Fitzgerald, E.; GaBhainn, S.N.; Sixsmith, J. Achieving consensus in developing a national set of child well-being indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 80, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Van Der Ent, R.; Eisner, S.; Bach, V.; Finkbeiner, M. Water accounting and vulnerability evaluation (WAVE): Considering atmospheric evaporation recycling and the risk of freshwater depletion in water footprinting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4521–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Child Trends. World Family Mapping: Family Change and Child Well-Being Outcomes; Child Trends: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Social Development. Children and Young People: Indicators of Wellbeing in New Zealand 2008; Ministry of Social Development: Wellington, New Zealand, 2008.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Headline Indicators for Children’s Health, Development and Wellbeing 2011; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Community Health Monitor Programme. Child Health Indicators of Life and Development; Rigby, M., Köhler, L., Eds.; European Union Community Health Monitoring Programme: Luxemburg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization) Regional Office for Europe. Social Determinants of Health and Well-Being among Young People; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). The State of the World’s Children 2014 in Numbers: Every Child Counts; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; WHO: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). PISA 2012 Results in Focus; OECD: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. The Benefits of Vocational Education and Training; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Legatum Institute. The Legatum Prosperity Index 2016; The Legatum Institute Foundation: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). Childinfo: Monitoring the Situation of Children and Women. Available online: http://www.childinfo.org/ (accessed on 11 March 2017).

- Malmö University. Oral Health Database. Available online: http://www.mah.se/capp/ (accessed on 25 August 2016).

- WHO (World Health Organization). Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2017).

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). UIS.Stat. Available online: http://data.uis.unesco.org/ (accessed on 11 August 2016).

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). OECD Family Database. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 21 October 2015).

- UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). Data and Analysis Statistics. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/statistics/index.html (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- European Commission. Eurostat. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 19 October 2015).

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 11 March 2017).

- CIA (Central Intelligence Agency). Sex Ratio at Birth. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2018.html (accessed on 20 March 2017).

- ITU (International Telecommunication Union). ITU—Statistics. Available online: http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx (accessed on 19 March 2017).

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). Income Gini Coefficient. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/income-gini-coefficient (accessed on 11 March 2016).

- UN (United Nations). Tier Classification for Global SDG Indicators; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). The State of the World’s Children 2016: A Fair Chance for Every Child; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). The State of the World’s Children 2015: Reimagine the Future, Innovation for Every Child; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Data Availability Level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top | Very High | High | Medium | Low | Very Low | No Available Statistical Data | |

| Numbers of covered country | 195 | 195 > N ≥ 175 | 175 > N ≥ 150 | 150 > N ≥ 100 | 100 > N ≥ 50 | 50 > N ≥ 1 | 0 |

| Data Availability Level | Covered Indicators | Covered Topics |

|---|---|---|

| Top data availability | 7 | 2 themes, |

| 3 subthemes, | ||

| 7 criteria | ||

| At least very high data availability | 34 | 5 themes, |

| 19 subthemes, | ||

| 29 criteria | ||

| At least high data availability | 44 | 5 themes, |

| 22 subthemes, | ||

| 41 criteria | ||

| At least medium data availability | 66 | 7 themes, |

| 29 subthemes, | ||

| 59 criteria | ||

| At least low data availability | 84 | 7 themes, |

| 33 subthemes, | ||

| 70 criteria | ||

| At least very low data availability | 139 | 7 themes, |

| 46 subthemes, | ||

| 98 criteria | ||

| No statistical data at country level | 154 | 7 themes, |

| 50 subthemes, | ||

| 109 criteria |

| Theme | Subtheme | Criteria | Indicator | Data Availability | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covered Countries | Level | |||||

| Health | Nutrition | Low birth weight | Percentage of infants born with low birth weight (<2500 g) | 187 | Very high | UNICEF Childinfo [45] |

| Overweight and obesity | Overweight (including obesity, %) | 146 | Medium | |||

| Breast feeding | Exclusive breastfeeding < six months (%) | 167 | High | |||

| Underweight | Underweight (moderate and severe, %) | 148 | Medium | |||

| Wasting | Children under five below minus two standard deviations from median weight-for-height (%) | 147 | Medium | |||

| Stunting | Children under five below minus two standard deviations from median height-for-age (%) | 147 | Medium | |||

| Child mortality | Infant mortality | Infant mortality rate (probability of dying between birth and age one per 1000 live births) | 195 | Top | ||

| Under-five mortality | Under-five mortality rate (probability of dying by age five per 1000 live births) | 195 | Top | |||

| Neonatal mortality | Neonatal mortality rate (during the first 28 completed days, per 1000 live births) | 195 | Top | |||

| Oral health | Dental treatments | DMFT (decayed, missing or filled teeth) among 12-year-olds | 180 | Very high | Malmö University Oral Health Database [46] | |

| Mental health | Suicide | Suicide rate, 15–29 year-olds, per 100,000 | 171 | Very high | WHO [40] | |

| Hazardous pollutant | Household and ambient air pollution | Mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution (per 100,000 population) | 172 | High | WHO [47] | |

| PM2.5 air pollution | PM2.5 air pollution, population exposed to levels exceeding WHO guideline value (% of total) | 187 | Very high | |||

| Immunization coverage | Measles containing vaccine (MCV) immunization | Measles (MCV) immunization coverage among one-year-olds (%) | 195 | Top | UNICEF [45] | |

| Diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis (DTP3) immunization | Diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis (DTP3) immunization coverage among one-year-olds (%) | 195 | Top | |||

| Polio (Pol3) immunization | Polio (Pol3) immunization coverage among one-year-olds (%) | 195 | Top | |||

| Hepatitis B (HepB3) immunization | Hepatitis B (HepB3) immunization coverage among one-year-olds (%) | 185 | Very high | |||

| Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunization | BacilleCalmette-Guérin (vaccine against tuberculosis) immunization coverage among one-year-olds (%) | 164 | High | |||

| Risk behavior | Alcohol use | Percentage of 15–19 years old heavy episodic drinkers | 189 | Very high | WHO; World Bank [47,52] | |

| Adolescent fertility | Adolescent fertility rate (per 1000 girls aged 15–19 years) | 184 | Very high | |||

| Physical behavior | Physical activity | Comparable estimates of prevalence of insufficient physical activity (adolescents 11–17 years) | 120 | Medium | WHO [42] | |

| Maternal health | Antenatal care | Percentage of women aged 15–49 years attended at least once during pregnancy by skilled health personnel (doctor, nurse or midwife) | 149 | Medium | UNICEF Childinfo [45] | |

| Maternal mortality | Maternal mortality ratio (MMR, maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) | 183 | Very high | |||

| Skilled attendant at birth | Percentage of births attended by skilled health personnel (doctor, nurse or midwife) | 168 | High | |||

| Health expenditure | Public health expenditure | Public health expenditure as % of total health expenditure | 190 | Very high | WHO; World Bank [47,52] | |

| Water and sanitation | Access to improved sanitation facilities | Improved sanitation facilities (% of population with access) | 191 | Very high | UNICEF; WHO; World Bank [45,47,52] | |

| Access to improved drinking-water sources | Population using improved drinking-water sources (%) | 193 | Very high | |||

| HIV | HIV prevalence among youth | Estimated percentage of young men and women (aged 15–24) living with HIV | 128 | Medium | UNICEF [57,58] | |

| Education | School attainment | Overall literacy | Youth literacy rate, population 1–24 years, both sexes (%) | 151 | High | UNESCO [48] |

| Repetition | Repetition rate in primary education (all grades), both sexes (%) | 165 | High | |||

| Completion of education | Primary school completion | Gross graduation ratio from primary education, both sexes | 107 | Medium | ||

| Secondary school completion | Gross graduation ratio from lower secondary education, both sexes (%) | 114 | Medium | |||

| Tertiary school completion | Gross graduation ratio from first degree programmes (ISCED 6 and 7) in tertiary education, both sexes (%) | 120 | Medium | |||

| Attendance of education | Enrolment in primary school | Gross enrolment ratio, primary, both sexes (%) | 191 | Very high | ||

| Enrolment in secondary school | Gross enrolment ratio, secondary, both sexes (%) | 188 | Very high | |||

| Enrolment in tertiary school | Gross enrolment ratio, tertiary, both sexes (%) | 175 | Very high | UNESCO [48] | ||

| Early childhood education | Enrolment of kindergarten | Gross enrolment ratio, pre-primary, both sexes (%) | 187 | Very high | ||

| Government support on education | Public expenditure on education | Government expenditure on education as % of GDP | 179 | Very high | ||

| Gender equality | Gender equality in enrolment | Gross enrolment ratio, pre-primary, gender parity index (GPI) | 176 | Very high | ||

| Gross enrolment ratio, primary, gender parity index (GPI) | 190 | Very high | ||||

| Gross enrolment ratio, secondary, gender parity index (GPI) | 187 | Very high | ||||

| Gross enrolment ratio, tertiary, gender parity index (GPI) | 177 | Very high | ||||

| Gender equality in graduation | Gross graduation ratio from primary education, gender parity index (GPI) | 134 | Medium | |||

| Gross graduation ratio from lower secondary education, gender parity index (GPI) | 134 | Medium | ||||

| Gross graduation ratio from first degree programmes (ISCED 6 and 7) in tertiary education, gender parity index (GPI) | 137 | Medium | ||||

| Gender equality in youth literacy | Youth literacy rate, population 1–24 years, gender parity index (GPI) | 152 | High | |||

| Safety | Violence and crime | Juvenile delinquency | Juveniles held in prisons, penal institutions or correctional institutions | 108 | Medium | UNODC [50] |

| Juveniles brought into formal contact with the police and/or criminal justice system, all crimes | 108 | Medium | ||||

| Criminal victimization | Intentional homicide count and rate per 100,000 population | 195 | Top | |||

| Assault and major assault rates in different countries (police recorded assaults/100,000 population) | 128 | Medium | ||||

| Sexual violence against children | Total sexual offences against children at the national level, police-recorded offences, rate per 100,000 children aged 17 or under | 102 | Medium | |||

| Birth registration | Registration of newborns | Birth registration rate | 166 | High | UNICEF [45] | |

| Child labor | Children involved in child labor | Percentage of children five-14 years old involved in child labor | 112 | Medium | ||

| Child marriage | Children married or in union | Percentage of women aged 20–24 years who were first married or in union before ages 18 | 123 | Medium | ||

| Demographic structure | Sex ratio | Sex ratio at birth | 191 | Very high | CIA [53] | |

| Economic status | Housing quality | Electricity coverage | Access to electricity (% of population) | 191 | Very high | World Bank [52] |

| Macroeconomic situation | Overall unemployment | Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate) | 170 | High | ||

| Youth unemployment | Youth unemployment rate (% of total labor force ages 15–24) | 170 | High | |||

| Macroeconomic situation | Income equality at societal level | Income Gini coefficient | 156 | High | UNDP [55] | |

| National income | GNI per capita, Purchasing power parity (current international $) | 183 | Very high | World Bank [52] | ||

| National debts | Public debt as percentage of GDP | 179 | Very high | CIA [53] | ||

| Relationship | Community relationship | Social capital | Social Capital Ranking | 140 | Medium | Legatum Institute [44] |

| Participation | Social media connection | Internet access in home | Proportion of households with internet access at home | 138 | Medium | ITU [54] |

| Access to public media | Proportion of households with computer | 126 | Medium | |||

| Environmental aspects | Freshwater vulnerability | Risk of depleting freshwater resources | Water depletion index (WDI) | 192 | Very high | Berger et al. [33] |

| Renewable energy consumption | Consumption of renewable energy | Renewable energy consumption (% of total final energy consumption) | 180 | Very high | World Bank [52] | |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Y.-J.; Lehmann, A.; Finkbeiner, M. Screening Indicators for the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI). Sustainability 2017, 9, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040518

Chang Y-J, Lehmann A, Finkbeiner M. Screening Indicators for the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI). Sustainability. 2017; 9(4):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040518

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Ya-Ju, Annekatrin Lehmann, and Matthias Finkbeiner. 2017. "Screening Indicators for the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI)" Sustainability 9, no. 4: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040518

APA StyleChang, Y.-J., Lehmann, A., & Finkbeiner, M. (2017). Screening Indicators for the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI). Sustainability, 9(4), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040518