Biocultural Homogenization in Urban Settings: Public Knowledge of Birds in City Parks of Santiago, Chile

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Bird Sampling

2.3. Citizen Surveys

2.4. Ethics Clearance

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bird Species Richness

3.2. Citizen Surveys

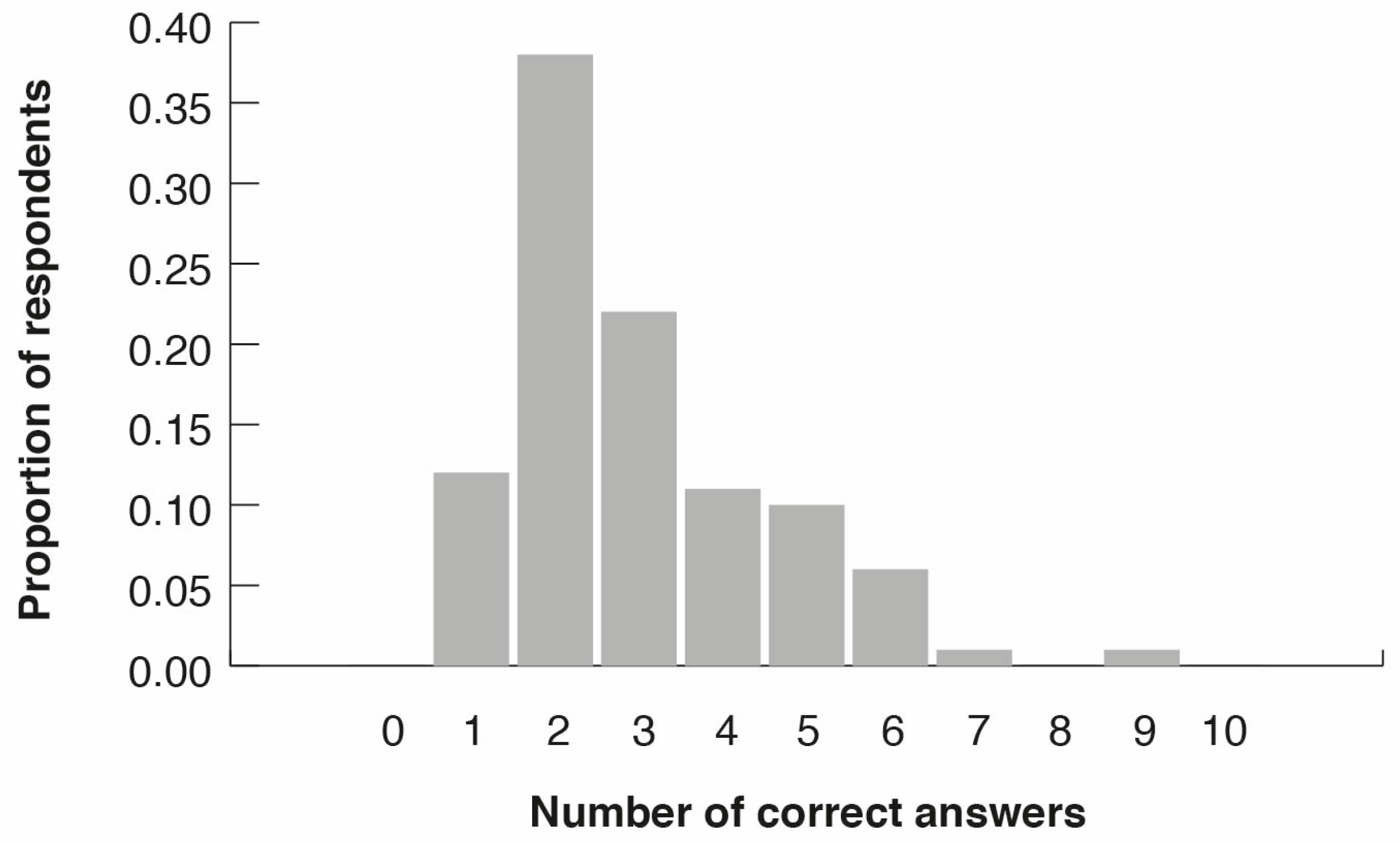

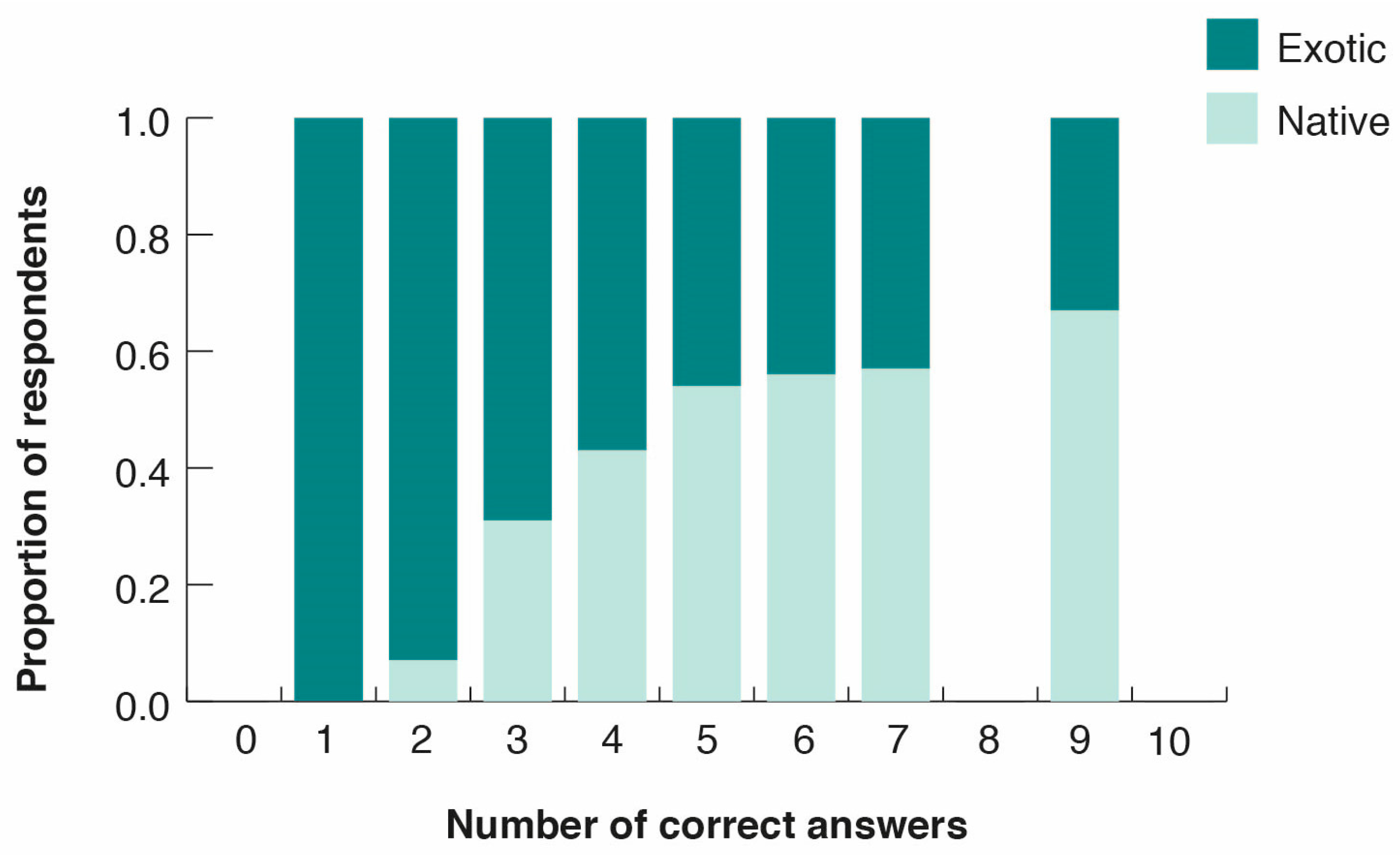

3.3. Peoples’ Perceptions of Bird Diversity

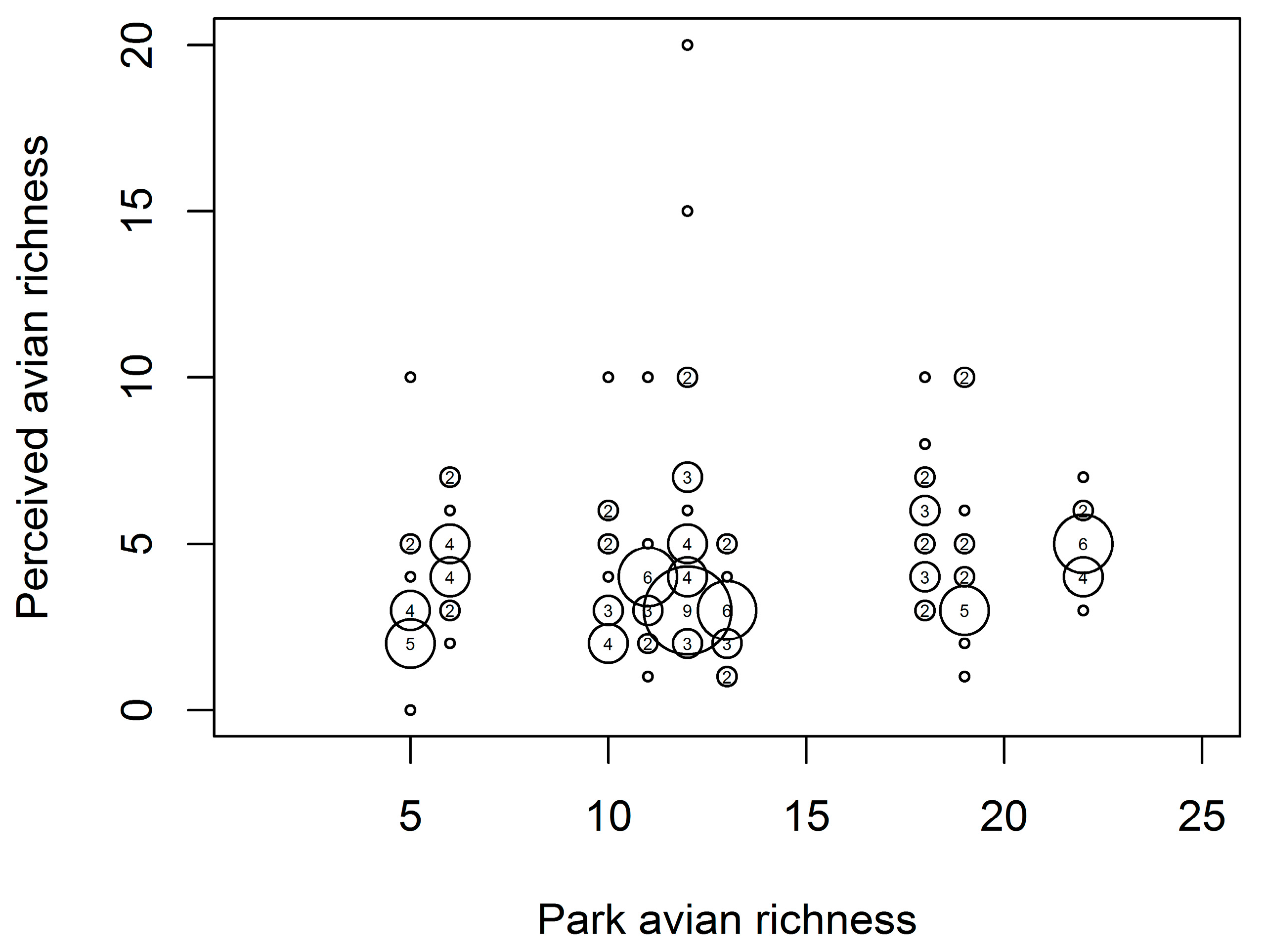

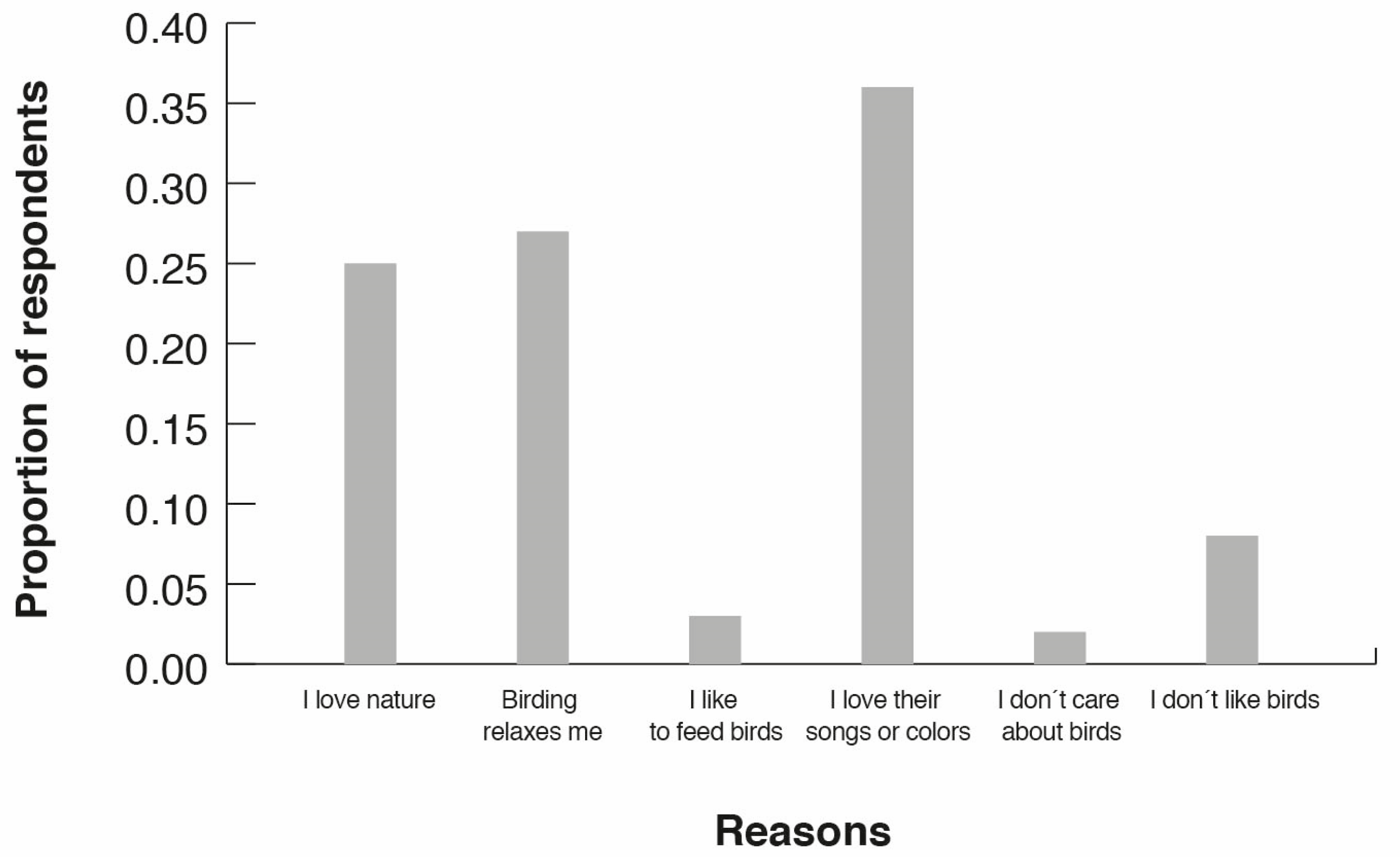

3.4. Birding Attitudes

4. Discussion

4.1. Bird Diversity in Santiago City Parks

4.2. Peoples’ Ability to Identify Birds in City Parks

4.3. Drivers of Biocultural Homogenization (Responsible for Limited Peoples’ Perceptions of Avian Diversity in City Parks)

- (i)

- Low proportion of greenspace per inhabitant within the city of Santiago: The consequence is that citizens find limited opportunities for direct encounters with local biodiversity, the so-called “extinction of experience” [8,9]. The area of greenspace available for direct encounters between people and wildlife can affect the residents’ familiarity with local biological diversity. In fact, the city of Santiago has a growing population of more than six million people with an average of only 4.5 m2 of greenspaces per capita, a ratio far below the 9 m2 recommended by the World Health Organization [39]. Consequently, citizens of Santiago have limited access to green areas where they can observe and learn about native biodiversity, despite the fact that more than 70% of the park visitors surveyed by us expressed their fondness for bird watching. Interestingly, Pilgrim et al. [40] proposed that the loss of ecological knowledge tends to be stronger among the inhabitants of more developed and urbanized countries with higher GDP (e.g., UK from 2010 to 2014 with a GDP of $41,836 USD [41]), in contrast to more rural and low-income countries (e.g., Indonesia with a GDP from 2010 to 2014 of $3521 USD [41]). In the case of Chile, with a GDP of $14,590 USD (2010–2014) [41] the situation should resemble that of lower-income countries. However, considering the biased distribution of world GPD, with a median of $5866 (n = 245 countries) [41], Chilean GPD is closer to the high-income and urbanized countries (percentile 75), with a current proportion of urban population that reaches 87% [42]. From our results, it seems likely that recent generations of city dwellers lack a relationship with rural environments, but further research is needed to explore this process. Similar to most Latin American cities, Santiago has been undergoing an intense process of urban densification in recent decades [43]. This process has led to the replacement of many residential neighborhoods, featuring houses with backyards, by apartment buildings, which means that a large proportion of the population currently has less access to greenspace where they can observe bird life in comparison to past residents.

- (ii)

- Taxonomic bias induced by the media in favor of iconic or exotic species: People in cities are strongly influenced by information from the media (i.e., movies, children’s TV, books, social networks), and notably from the Internet. However, information about wild species in the media concentrates largely on a few iconic, appealing, and often exotic species [10]. For example, an analysis of 1254 schoolbooks and children’s books accessible to citizens of Santiago showed that illustrations and narratives were dominated by charismatic species and landscapes from Africa and the Northern Hemisphere (particularly Europe), with sparse reference to Chilean native biodiversity [44]. A similar phenomenon may be occurring in other Latin American countries where urbanization is expanding rapidly. For example, in the Andean region of Cuenca, Ecuador, Rozzi [7] found that roses and exotic plants prevailed in classroom decoration and in textbooks used in rural schools, ignoring the notably rich native flora and fauna occurring outside the school. A frequent consequence of this bias towards exotic species in literature, schools, and the media is the substitution of common local names by exotic ones. In our survey of park visitors in Santiago, most of the respondents erroneously identified the native Austral Blackbird as a North American or European Crow (13 out of 17 respondents), a group of birds that is not present in Chile or in South America.

4.4. Biodiversity and Human Wellbeing

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2007 Revision. 2008. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wup2007/2007WUP_Highlights_web.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2016).

- Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Lubchenco, J.; Melillo, J.M. Human Domination of Earth’s Ecosystems. Science 1997, 277, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzluff, J.M.; Ewing, K. Restoration of fragmented landscapes for the conservation of birds: A general framework and specific recommendations for urbanizing landscapes. Restor. Ecol. 2001, 9, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzluff, J.M.; McGowan, K.J.; Donnelly, R.; Knight, R.L. Causes and consequences of expanding American Crow populations. In Avian Ecology and Conservation in an Urbanizing World; Marzluff, J.M., Bowman, R., Donnelly, R., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Press: Norwell, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 331–363. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, M.; Lockwood, J. Biotic homogenization: a few winners replacing many losers in the next mass extinction. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M. Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 127, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzi, R. Biocultural Ethics: From Biocultural Homogenization toward Biocultural Conservation. In Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World: Values, Philosophy, and Action; Rozzi, R., Pickett, S.T.A., Palmer, C., Armesto, J.J., Callicott, J.B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human–nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.R. Biodiversity conservation and the extinction of experience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballouard, J.M.; Brischoux, F.; Bonnet, X. Children prioritize virtual exotic biodiversity over local biodiversity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozzi, R.; Silander, J., Jr.; Dollenz, O.; Massardo, F.; Anderson, C.; Connolly, B. Árboles nativos y exóticos en las plazas de Magallanes. An. Inst. Patagon. Ser. Cienc. Nat. 2003, 31, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi, R.; Anderson, C.B.; Massardo, F.; Silander, J., Jr. Diversidad Biocultural Subantártica: Una Mirada Desde el Parque Etnobotánico Omora. Chloris Chilensis 2001, 4. Available online: http://www.chlorischile.cl/rozzi/rozzi.htm (accessed on 22 March 2017).

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, K.N.; Fuller, R.A.; Devine-Wright, P.; Tratalos, J.; Payne, S.R.; Warren, P.H.; Lomas, K.J.; Gaston, K.J. Ecological and psychological values of urban green space. In Dimensions of the Sustainable City; Jenks, M., Jones, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Fuller, R.A.; Bush, R.; Lin, B.B.; Gaston, K.J. The health benefits of urban nature: How much do we need? Bioscience 2015, 65, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallimer, M.; Irvine, K.N.; Skinner, A.M.J.; Davies, Z.G.; Rouquette, J.R.; Maltby, L.L.; Warren, P.H.; Armsworth, P.R.; Gaston, K.J. Biodiversity and the Feel-Good Factor: Understanding Associations between Self-Reported Human Well-being and Species Richness. Bioscience 2012, 62, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz, A.; Turbe, A.; Simon, L.; Julliard, R. Enhancing urban biodiversity and its influence on city-dwellers: an experiment. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 171, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Junge, X.; Matthies, D. The influence of plant diversity on people’s perception and aesthetic appreciation of grassland vegetation. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, A. Urban awareness and attitudes toward conservation: A first look at Canada’s cities. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 54, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, S. A Bird in the Bush. A Social History of Bird Watching; Aurum Press Ltd.: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, J.E. Effect of sample size, plot size, and counting time on estimates of avian diversity and abundance in a Chilean rainforest. J. Field Ornithol. 2000, 71, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D. Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R. Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2008; Available online: www.R-project.org (accessed on 24 August 2016).

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using {lme4}. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudoux, P. Pgirmess: Data Analysis in Ecology, R Package Version 1.5.8; 2013. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pgirmess (accessed on 24 August 2016).

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Elphick, C.S. A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2009, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estades, C.F. Aves y vegetación urbana, el caso de las plazas. Boletın Chileno de Ornitologıa 1995, 2, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, I.A.; Armesto, J.J. La conservación de aves silvestres en ambientes urbanos de Santiago. Ambiente y Desarrollo 2003, 19, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, B.S.; Inger, R.; Gaston, K.J. A Rose by any other name: Plant identification knowledge & socio-demographics. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquiza, A.; Mella, J.E. Riqueza y diversidad de aves en parques de Santiago durante el período estival. Boletın Chileno de Ornitologıa 2002, 9, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Villagrán, C.; Villa, R.; Hinojosa, L.; Sánchez, G.; Romo, M.; Maldonado, A.; Cavieres, L.; Latorre, C.; Cuevas, J.; Castro, S.; et al. Etnozoología Mapuche: Un estudio preliminar. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 1999, 72, 595–627. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi, R.; Massardo, F.; Anderson, C.B.; Clark, G.; Egli, G.; McGehee, S.; Ramilo, E.; Calderón, U.; Calderón, C.; Aillapan, L.; et al. Multi-Ethnic Bird Guide of the Sub-Antarctic Forests of South America; University of North Texas Press and University of Magallanes Press: Magallanes, Chile, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M.; Mujica, M.I.; Vio-Garay, M.F.; Gelcich, S.; Armesto, J.J. Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Chile. State of the Art and Potential Contribution to Improve Management and Conservation. 2016. Available online: https://ethnobiology.org/traditional-ecological-knowledge-chile-state-art-and-potential-contribution-improve-management-and-c (accessed on 22 March 2017).

- Neruda, P. Arte de Pájaros; Editorial Lozada: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, J.T.; Barreau, A.; Altamirano, T.A. Sobre plumas y folclore: Presencia de las aves en refranes populares de Chile. Boletın Chileno de Ornitologıa 2013, 19, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Clergeau, P.; Croci, S.; Jokimäki, J.; Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.L.; Dinetti, M. Avifauna homogenisation by urbanisation: analysis at different European latitudes. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 127, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Packe, S.; Figueroa, I.M. Distribución, superficie y accesibilidad de las áreas verdes en Santiago de Chile. EURE 2010, 36, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, S.E.; Cullen, L.C.; Smith, D.J.; Pretty, J. Ecological knowledge is lost in wealthier communities and countries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Bank. GDP per Capita (Current US$). 2016. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed on 29 November 2016).

- INE. Compendio Estadístico. 2010. Available online: http://www.ine.cl/canales/menu/publicaciones/compendio_estadistico/pdf/2010/1.2estdemograficas.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2016).

- Borsdorf, A.; Hidalgo, R. Revitalization and tugurization in the historical centre of Santiago de Chile. Cities 2013, 31, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celis-Diez, J.L.; Díaz-Forestier, J.; Márquez-García, M.; Lazzarino, S.; Rozzi, R.; Armesto, J.J. Biodiversity Knowledge Loss in Children’s books and texts. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 4, 408–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemésio, A.; Seixas, D.P.; Vasconcelos, H.L. The public perception of animal diversity: What do postage stamps tell us? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weilbacher, M. The renaissance of the naturalist. J. Environ. Educ. 1993, 25, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M.; Arvai, J. Knowledge as a driver of public perceptions about climate change reassessed. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Plummer, K.E.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Fuller, R.A.; Anderson, K.; Hancock, S.; Gaston, K.J. Doses of Neighborhood Nature: The Benefits for Mental Health of Living with Nature. BioScience 2017, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Gaston, K.J. Likeability of Garden Birds: Importance of Species Knowledge & Richness in Connecting People to Nature. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Cervantes, M.; Schondube, J.E.; Castillo, A.; MacGregor-Fors, I. How do people perceive urban trees? Assessing likes and dislikes in relation to the trees of a city. Urban Ecosyst. 2014, 17, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, G.; Beaty, R.M.; Doherty, M. Urban Greenspace: Connecting People and Nature. In Proceedings of the Second State of Australian Cities Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 30 November–2 December 2005; Available online: https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/81376/environmental-city-13-barnett.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2016).

- Bayne, E.M.; Campbell, J.; Haché, S. Is a picture worth a thousand species? Evaluating human perception of biodiversity intactness using images of cumulative effects. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 20, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Park Name | County within Santiago City | Coordinates | Park Size (ha) | Total Bird Richness | Sampled Points | Visitors Surveyed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude S | Longitude W | ||||||

| Parque Bicentenario | Vitacura | 33°23.725′ | 70°36.086′ | 60.0 | 22 | 4 | 14 |

| Parque Araucano | Las Condes | 33°24.137′ | 70°34.378′ | 29.2 | 19 | 4 | 14 |

| Parque Juan Moya | Ñuñoa | 33°27.970′ | 70°35.337′ | 15.0 | 18 | 4 | 14 |

| Parque Santa Rosa | Las Condes | 33°25.080′ | 70°32.364′ | 7.0 | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| Plaza Las Lilas | Providencia | 33°25.650′ | 70°35.677′ | 2.2 | 11 | 2 | 14 |

| Plaza Isabel La Católica | Las Condes | 33°25.612′ | 70°34.729′ | 0.6 | 12 | 1 | 16 |

| Plaza Del Inca | Las Condes | 33°24.792′ | 70°34.211′ | 1.1 | 5 | 1 | 14 |

| Parque Alcalde Chadwick | La Reina | 33°26.118′ | 70°33.469′ | 2.0 | 6 | 2 | 14 |

| Plaza Sebastian El Cano | Las Condes | 33°25.676′ | 33°25.676′ | 0.8 | 18 | 1 | 14 |

| Plaza Castillo Velasco | Ñuñoa | 33°27.578′ | 70°35.487′ | 0.2 | 12 | 1 | 13 |

| No. | Model Specification | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 𝑅𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐 = α | Intercept only model |

| 2 | 𝑅𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐 = 𝛼 + 𝑜𝑓𝑓𝑠𝑒𝑡(log𝑆𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘) | Park size offset on perceived avian richness. |

| 3 | 𝑅𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐 = 𝛼 + 𝛽1𝑅𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 + 𝑜𝑓𝑓𝑠𝑒𝑡(log𝑆𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘) | Linear relationship between park avian richness plus sampling offset of park area on the perceived avian richness. |

| 4 | 𝑅𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐 = 𝛽1𝑆𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 | Linear effect of park size on perceived avian richness. |

| 5 | 𝑅𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐 = 𝛼 + 𝛽1𝑅𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 + 𝛽2𝑅2𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 | Second-order polynomial effect of park avian richness on perceived richness. |

| 6 | 𝑅𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐 = 𝛼 + 𝛽1𝑅𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 + 𝛽2𝑆𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 + 𝛽3𝑅𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘×𝑆𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 | Interactive effect of park avian richness and park area. |

| 7 | 𝑅𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐 = 𝛼 + 𝛽1𝑅𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 + 𝛽2𝑅2𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 + 𝛽3𝑆𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 | Second order polynomial relationship between perceived richness and park richness, plus additive effect of park size |

| 8 | 𝑅𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑐 = 𝛼 + 𝛽1𝑅𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 + 𝛽2𝑅2𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘 + 𝑜𝑓𝑓𝑠𝑒𝑡(log𝑆𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑘) | Second order polynomial relationship between perceived richness and park richness, plus an offset to park size |

| Scientific Names | Local Names | Origin | Mean Abundance (Birds/Point/Day) ± SD | Frequency of Occurrence (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turdus falcklandii | Austral Thrush | Native | 7.88 ± 9.05 | 1 |

| Columba livia | Feral Dove | Exotic | 5.16 ± 7.35 | 0.8 |

| Myiopsitta monachus | Monk Parakeet | Exotic | 4.01 ± 7.15 | 0.9 |

| Zenaida auriculata | Eared Dove | Native | 3.42 ± 4.23 | 1 |

| Zonotrichia capensis | Rufous-collared Sparrow | Native | 2.27 ± 2.33 | 0.8 |

| Molotrhus bonariensis | Shiny Cowbird | Native | 1.28 ± 6.06 | 0.6 |

| Vanellus chilensis | Southern Lapwing | Native | 0.88 ± 4.14 | 0.4 |

| Agelaius thilius | Yellow-winged Blackbird | Native | 0.79 ± 3.53 | 0.1 |

| Curaeus | Austral Blackbird | Native | 0.77 ± 1.84 | 0.7 |

| Troglodites aedon | Southern House Wren | Native | 0.65 ± 0.86 | 0.5 |

| Sporagra barbata | Black-chinned Siskin | Native | 0.53 ± 2.07 | 0.3 |

| Passer domesticus | House Sparrow | Exotic | 0.52 ± 1.10 | 0.5 |

| Elaenia albiceps | White-crested Elaenia | Native | 0.44 ± 1.16 | 1 |

| Milvago chimango | Chimango Caracara | Native | 0.42 ± 0.93 | 0.7 |

| Anairetes parulus | Tufted Tit-Tyrant | Native | 0.39 ± 0.73 | 0.5 |

| Phytotoma rara | Rufous-tailed Plantcutter | Native | 0.35 ± 0.92 | 0.8 |

| Diuca | Comon Diuca-Finch | Native | 0.31 ± 0.77 | 0.5 |

| Leptasthenura aegithaloides | Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail | Native | 0.31 ± 0.61 | 0.6 |

| Mimus thenca | Chilean Mockingbird | Native | 0.28 ± 0.70 | 0.4 |

| Sturnella loyca | Long-tailed Meadowlark | Native | 0.25 ± 0.90 | 0.2 |

| Tachycineta meyeni | Chilean Swallow | Native | 0.24 ± 0.93 | 0.4 |

| Sicalis luteola | Grassland (Misto) Yellow-finch | Native | 0.02 ± 0.27 | 0.1 |

| Model | LL | AICc | Δ AICc | wic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −307.3 | 618.67 | 0.00 | 0.41 |

| 4 | −306.8 | 619.76 | 1.09 | 0.23 |

| 6 | −304.7 | 622.10 | 1.16 | 0.23 |

| 5 | −306.7 | 622.36 | 2.98 | 0.09 |

| 7 | −306.4 | 623.15 | 4.54 | 0.04 |

| 8 | −319.1 | 656.59 | 27.76 | 0 |

| 3 | −321.8 | 656.76 | 31.16 | 0 |

| 2 | −326.3 | 656.97 | 38.10 | 0 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Celis-Diez, J.L.; Muñoz, C.E.; Abades, S.; Marquet, P.A.; Armesto, J.J. Biocultural Homogenization in Urban Settings: Public Knowledge of Birds in City Parks of Santiago, Chile. Sustainability 2017, 9, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040485

Celis-Diez JL, Muñoz CE, Abades S, Marquet PA, Armesto JJ. Biocultural Homogenization in Urban Settings: Public Knowledge of Birds in City Parks of Santiago, Chile. Sustainability. 2017; 9(4):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040485

Chicago/Turabian StyleCelis-Diez, Juan L., Cesar E. Muñoz, Sebastián Abades, Pablo A. Marquet, and Juan J. Armesto. 2017. "Biocultural Homogenization in Urban Settings: Public Knowledge of Birds in City Parks of Santiago, Chile" Sustainability 9, no. 4: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040485

APA StyleCelis-Diez, J. L., Muñoz, C. E., Abades, S., Marquet, P. A., & Armesto, J. J. (2017). Biocultural Homogenization in Urban Settings: Public Knowledge of Birds in City Parks of Santiago, Chile. Sustainability, 9(4), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040485