1. Introduction

In the last decades, Albania has experienced the growth of its reputation on the tourist destination market in the Mediterranean basin, in an evolution process which started in 1992 that, characterized as “the Waking Sleeping Beauty”, led it to the rank of the most recommended destination in 2011 [

1].

Much of the credit for this belongs to its peculiar geographic conformation, that concentrates many sites and points of interests in a relatively small area. Other reasons are to be found in the huge amount and variety of the built environment, resulting from subsequent stratifications [

2] and in the equally rich and variegated natural resources: mountain areas and beaches can be often visited within a single day. Actually, even if we cannot talk about ‘mass’ tourism, coastal zones in particular are currently (more precisely since 2015) the scene of a “tourism boom”, demonstrated by the abundance of resorts built to support the ‘sea-and-sand’ segment, with an intensive and uncontrolled development, not supported through adequate infrastructuring processes. Nevertheless, it is estimated that 80% of total coasts still remain untouched by human modifications [

3].

Already in 2010, the growth rate in the number of visitors was much higher than in the other countries of the region, with 50% of yearly arrivals concentrated in July and August. Most flows (72% in 2010) occur by road, thus producing considerable impacts on the ecosystem and on the whole territory with specific reference to transport.

Indeed, another massive heritage remains undiscovered, which is represented by inland areas that—differently from coastal zones, gradually abandoned in time by their inhabitants for their undefended nature against hostile attacks and only recently re-evaluated—represent the most genuine and profound expression of local communities’ culture.

Other remarkable features of the scene are the increase in the number of visits to bigger towns’ attractions, the establishing of a specific interest among non-resident Albanians and the emerging of three fast-growing segments: cultural tourism, adventure tourism and ecotourism [

2]. The limited increase in the related revenues shows a rise in the number of low-income visitors and a decrease in the duration of stays.

In this context, the paper describes a research carried out at the Construction Technologies Institute—National Research Council of Italy. Based on a detailed analysis of the Albanian tourism sector, with its potentialities and gaps in sustainability and concrete tools for its achievement, it aims to present one possible solution in the field of mobile apps. The objective of the study is to give and discuss a tool for the promotion of Tirana’s “total heritage”.

The aim of the research is to amplify the so-called “wow-effect”, central in the current Albanian promotion strategy, considering the complex of components that visitors meet in local contexts, from history to social systems, values and surrounding in which he is immersed.

The framework used in the research articulates as follows.

Firstly, a description of the tourist sector of Albania is presented, as deduced from available literature and media reports and above all from major technical report that form the basis of the official National promotion Strategy. Then, the article analyzes with a critical lens the Strategy adopted by the central government, by focusing on its ground principles, governance-related issues and action instruments and matching it against, on one hand, conceptual references that can be found in the international scientific discourse and, on the other hand, actual signs of ‘what is happening in Albania’ from a more concrete perspective. This aims at deriving a measure of the distance existing between the country’s needs and possible solutions and give a tangible contribution, in the field of ICTs, as befitting as possible.

Secondly, the relationship between sustainable smart tourism and mobile applications is explored with a review process in order to identify the usefulness of a mobile app from the points of view of tourist and destination.

In the following paragraphs, a desk research on the market of available mobile apps related to the Albanian heritage, supporting tourism and knowledge of the country, is then presented, through a taxonomy that identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the different solutions adopted; then, the design and development process of our ‘SOS-Tirana’ app is explained.

Lastly, the achievements of the research work are widely discussed, analyzing the results and the innovativeness of the designed app.

The research is significant because it focuses on the active role of tourists and residents at the same time, through the app tool. It promotes the creation and valorization of local resources through the ease of access to attractions, a sense of belonging to the cultural heritage, the ability to engage the end-user, the possibility for different visitors to make personal planning and paths.

The ultimate ambition of the work is to contribute to the overcoming of the negative view of the country perceived abroad in order to provide a new image of Albania in the international scene, triggering, through the “SOS-Tirana” app, a process of re-appropriation of identity by local population.

2. The Albanian Tourism Sector: Lights and Shadows of Current Scenario

The current scenario of Albania reveals a country that, in a region marked by the mono-focus specialization of neighbouring nations (Greece, Turkey, Croatia) in the sea-and-sand segment, has a unique opportunity to distinguish itself in the market, out of a heavy competition offering narrow profit margins, thanks to the manifold character of its heritage.

Actually, the country has not created a real, strong ‘image’ or, in marketing terms, a ‘brand’ in the tourism sector; to understand the reasons for this, historical, political and social factors need to be considered, and sector policies need to be looked at from a critical perspective.

First of all, the studies and analysis which have been carried out [

1,

3,

4,

5], as well as program documents, agree on the absence of a real awareness of Albania as a tourist product both among tourists and among Albanian themselves.

Indeed, this issue has been thoroughly analyzed in [

6,

7,

8]: due to a hard and aching past, after the 1990s, the main trend was the destruction of anything that could recall the communist regime, in all its tangible and intangible repercussion on the people’s life. Up to now, against the awareness of the strategic role of tourism for the country’s economic growth, the architectural heritage, for example, has not received equal attention, to the extent that the heritage-related strategy has been long ‘included’ in the wider tourism strategy [

9]. Understandably, a conscious strategy for the promotion abroad of a cultural patrimony that everyone has preferred to erase in order to take on a radical restart has never come into fulfilment.

In the last decades, Albania has been—and is still—engaged in a very challenging phase of re-creation of its identity and of its presence in the international scenario, made more demanding through the need to rub out its negative reputation abroad [

1,

2,

10,

11]. Many efforts are being made here, showing a newly-acquired consciousness of the need to reconnect to other countries to face together common challenges. The process towards the alignment and the ratification of European and UNESCO instruments is very recent [

12].

Up to now, although three years have passed since the Draft National Tourism Strategy for 2014–2020, tourism has not yet an adopted strategy for sustainable development, as assessed through the ‘performance audit’ carried out by the Supreme State Audit body (SSA) in the former Ministry of Economic Development, Trade, Tourism and Enterprise. As a matter of fact, the draft for the period 2017 to 2022 resulted as being based on unrealistic data [

13].

For this reason, and given that tourism and cultural heritage are strictly intertwined in the development process of the country, we are of the view that the document that can best give an exhaustive picture of the official position and of current policies in the tourism sector, alongside the Tourism Strategy of Albania [

4], is above all the Albanian Culture Marketing Strategy [

2].

On the other hand, as will be shown in the following, cultural heritage, that until recent times [

12] did not have a dedicated strategy but was instead—and still is being—brought within the borders of the wider national tourism strategy, is increasingly regarded as being crucial for tourism development, to a point that it is considered strictly functional to it. It makes sense, then, when discussing on tourism in Albania, to focus attention on cultural heritage, also at the level of reference documents.

The current national strategy for culture marketing in the development of tourism has clearly stressed two main objectives:

The former is closely intertwined with a strong intent to promote cultural heritage also among Albanians to stimulate pride and sense of belonging to a precise collective and territorial identity. Therefore, at least in propositions, the national strategy is marked through actions having twin targets: tourists and residents. The latter clearly reveals the instrumental character, in monetary terms, of any resource ‘expendable’ on the tourist market, and, then, also of cultural heritage. Apart from expressed goals, the strategy adopted by the government undeniably presents some interesting elements: the methodology for market analysis, the introduction of relatively new concepts and the instruments for action.

2.1. Analysis Methodology

The national strategy is based on an acute and exhaustive market analysis, exploring rationally and in detail potentialities, limitations and characters of the ‘product’, target profiling and future directions. Potentialities have been described above; about Albania’s negative image, three main causes are identified [

2]:

Historical events and the consequences of dictatorial regimes: impoverishment, underdevelopment

The limited coverage of foreign media

The lack of information on resources

the latter being responsible also for the poor awareness among residents.

In the literature available, many sources agree on the fact that Albania is associated, abroad, with a negative image [

1,

2,

10,

11]. The analyses of Hall [

14] and Heusinger [

10] go beyond this, leading to admit the possible existence of a difficult, mutual mistrust relationship between the Albanians and, in general, other peoples, stressing the fact that, at the same time, also foreigners and international tourists appear to be misunderstood within the country.

To a certain extent, up to recent times, this situation could be confirmed in facts; and, indeed, such mistrust of the Albanian towards all that is ‘foreign’ may be the inheritance of years of isolation in which, although tourism was not expressly forbidden, a sharp separation between tourists and residents was actually pursued in the use of places and transport means [

14] and in many other practical respects through the so-called ‘prescriptive tourism’ [

7].

What, instead, can be witnessed in current times is the fact that some countries are seeking ways to get closer to Albania, having grasped its potential, above all thanks to the value of its cultural and natural heritage. A meaningful example of this is represented by the recent call launched for 2018 by the local US Embassy for heritage preservation projects, in which the direct support to US treaty maintaining or the creation of bilateral agreements, with a direct involvement of the financing body in the management sphere, as a clear sign of awareness and understanding of potential success [

15]. Just as important is the support at the operational level, offered by the Albanian–American Development Foundation, for knowledge transfer and local communities’ enablement in heritage management with new technologies and skills, through a number of projects. Some examples are the Support Program for the National Park of Butrint, the Regional Restoration Camps (a training program on theory and practice of restoration techniques for local residents) and the creation of ‘Culture Corps’ (an experience of know-how transfer to local stakeholder on cultural entrepreneurship) [

16]. To this, EU support to built heritage preservation projects and the engagement of the International Monetary Fund for the implementation of a financial discipline program and the increase of a dedicated budget can be added, as well as the manifold support from foreign foundations cited in [

17].

The main problems of Albanian destinations have been identified in the official strategy in

Inadequate infrastructures;

Lack of quality accommodation facilities (actually, standards have never been adopted, so provisions or regulations for the compliance to minimum quality levels are not available);

Chaotic costal development, not connected to infrastructure requisites;

Lack of qualification both in accommodation industry and among cultural resources managers and operators.

Within the official document, the analysis of destination from the point of view of ‘market readiness’ is particularly accurate; macro-criteria for evaluation (access–services–destination interpretation–advertising–intrinsic interest) are identified and matched against different tourist types, taking into consideration their variability according to the specific site. Such an analysis, from which however the uniqueness of the Albanian potential offer clearly emerges, allows us to assess that the market readiness level of many sites and destinations is actually very low; in other words, they do not match tourists’ exigencies.

Specific attention has been given in the document analyzed to the delineation of the image perceived from Albanians living abroad; the considerable number of Albanians across the world because of historical-political events, war-related destruction and economic involution is recognized as having a strategic importance, due to their capacity both to activate in their adopted countries a virtuous word-of-mouth, capable of arousing interest in a visit (greater revenues), and to invert brain-drain trends by persuading people with higher skills and qualifications (increase of the general socio-economic level) to come home.

Just as lucidly, the analysis carried out by the strategy’s authors deduces that, despite the singular wealth and size of cultural heritage resulting from the many ethnic stratifications, which is hardly matched among other countries, this is not enough to distinguish Albania from other Mediterranean competitors as a cultural tourism destination. It follows that a different offer is necessary, marked by a different identifying element. This has been recognized in its nature of the country ‘to discover’, ‘unknown’, to be transferred in a ‘multifaceted’ tourist offer on the experiential level, able to ‘impress’ on many sides at the same time. The definition of the overall offer is achieved through a ‘stratified’ approach, with respect to the visitors’ geographic provenience and to the respective level of interest, with a precise construction of the grid ‘tourists’ provenience/tourists’ type/type of offer’.

2.2. Conceptual Issues

Some conceptual implications, presented within the Strategy, are very interesting.

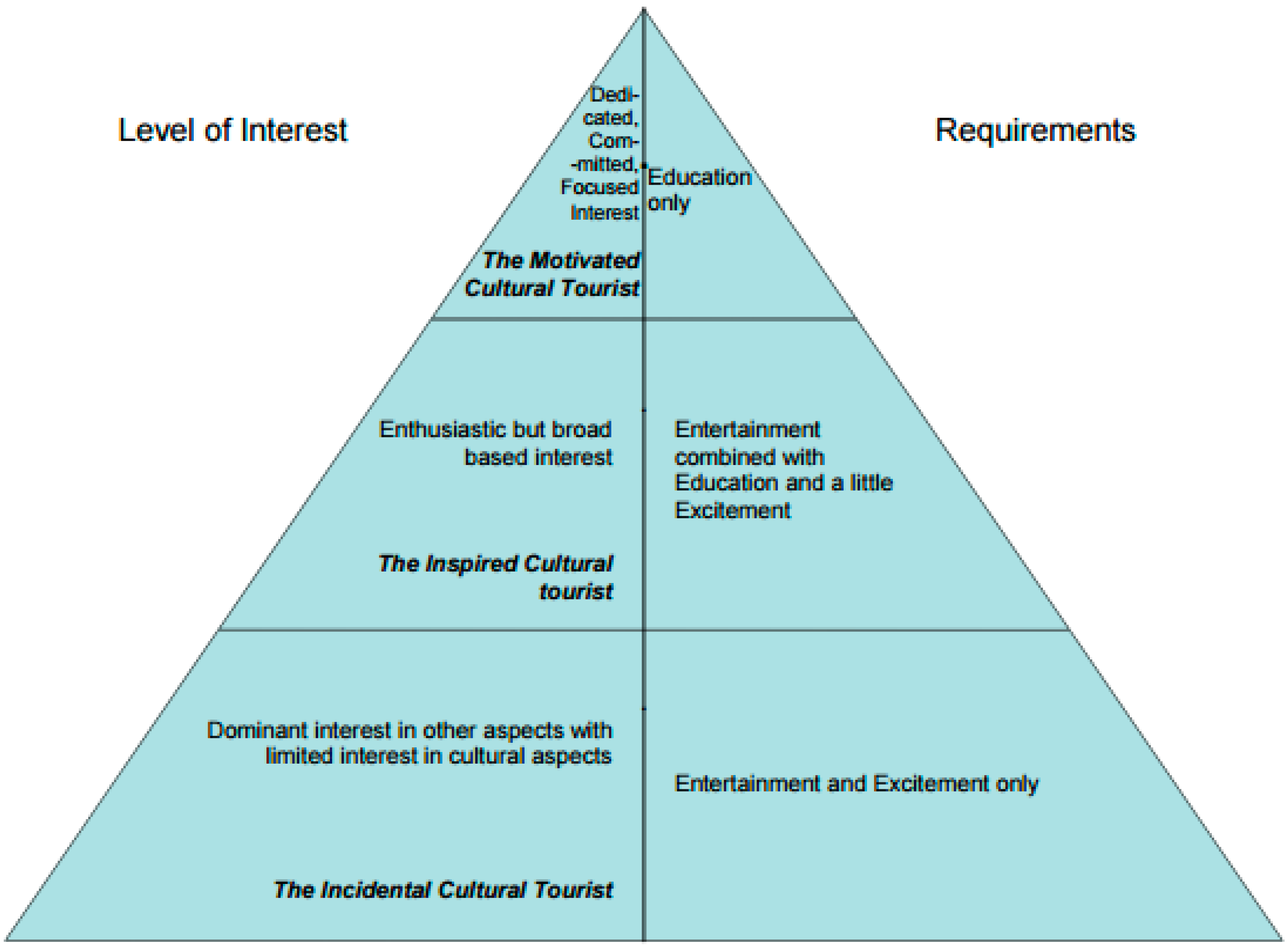

The ‘3E’ concept: One of the strategy’s key-concepts is the need for the tourist offer to fulfil the so called ‘3 Es’ representing the purpose of a visit: ‘education’, ‘entertaining’, ‘excitement’. These are then matched with as many tourist ‘types’, identified according to their attitude towards cultural heritage (‘motivated’–‘inspired’–‘incidental’) (

Figure 1).

These tourist ‘types’ form a sort of ‘triangle’, having at its top a limited number of visitors with specific academic or generally research-based interest, at any rate having a marked involvement towards cultural heritage, with purely educational expectations in relation to the visit experience (‘motivated tourists’). The intermediate area of the triangle is represented by the more numerous ‘inspired’ tourists, sincerely interested in the cultural dimension of the stay but having wider expectations in terms of education and entertainment and only a little interested in being ‘impressed’ or ‘surprised’. The triangle base is represented by the widest group of the so-called ‘incidental’ tourists, mainly interested in entertainment and in the ‘impressive’ force of the visited places.

Starting from the observation of the higher revenues associated to the last two brackets—more numerous—in respect to ‘motivated’ visitors, genuinely interested in cultural tourism in strict sense, the necessity to focus on the definition of a composite tourist offer is deduced, based on a re-definition of visit as a variegated ‘experience’ of the cultural, natural, seaside, gastronomic dimensions and, ultimately, of a complex environment of which the tangible heritage is only a facet, able to offer manifold inspirations. Essentially, cultural tourism is brought back in the wider concept of experiential tourism, considering it—when interpreted as tourism of the tangible heritage—insufficiently representative of behaviours and preferences of most visitors.

The ‘total heritage’ concept: This refers to the widest interpretation of cultural heritage. ‘Total heritage’ represents, in the official ‘vision’ expressed by the strategy, all of the ways (lifestyles) in which a community expresses itself in relation to its history, social systems, values and surrounding environment, then to the entirety of components that can be experienced when coming in contact with a local entity. This interpretation is, indeed, fully in line with the definition of cultural heritage as “

whatever is distinctive about the ‘way of life’ of people, community, nation or social groups” [

18]. The definition of the experiential aspect is then supported through the identification of criteria allowing to assess a destination’s merit to be worth visiting. Most visitors are not able to fully appreciate the specific implications of heritage, but are attracted by ‘impressive’ resources (the so called “wow-effect”). Their needs—basically, obtaining enjoyment in a non-demanding way—must also be considered according to specific criteria for resource evaluation: accessibility, closeness to other attractions, impressive character of location, impressive character of specific features, affinity to visitors’ own heritage, uniqueness, links to well-known figures (celebrities, characters, myths), engaging power (for example, ease of comprehension or closeness to own everyday life). According to the official document, 130 assets have been identified as having those attributes, coupled anyway with the low market-readiness level mentioned above.

The ‘geotourism’ concept: In this vision, intriguing—and directly linked to the ‘total heritage’ formulation—is the shift from the concept of ‘ecotourism’ to that of ‘geotourism’. This term, actually coined by the National Geographic, is explored in the analysis and strategically embraced by the Albanian strategy. In this transition, the basic reasoning remains the same—managing tourism in a way that it ‘pays’ to protect places rather than damaging them—but the application is extended to the destination meant as a complex in which nature is only a part. ‘Geotourists’ are visitors interested in experiencing “the cultural heritage of the countries they visit as part of their growing engagement with, and desire for, direct access to all authentic aspects of their chosen destinations” [

2]; the tourism of cultural heritage in strict sense is then a component of geotourism.

This tourism model finds its completion by identifying two wide concept-areas that can be assumed as directions for concrete actions:

A ‘pull’ approach: the on-site appealing action exerted by local resources, that brings visitors in contact with places;

A ‘push’ approach: implemented by a system of actions (through exhibitions, foreign media, fairs, conferences, etc.), able to stimulate the visit desire and decision from abroad.

In expressed intentions and in the observation perspective, then, the current strategy for the promotion of the tourist sector appears as built on a consistent basis. However, putting aside propositions and reading the analysis document between the lines, something seems to be missing or not working in the identification of solutions and operational modes.

2.3. Governance

The approach of tourism policies that can be drawn from the reading of the official document, is “a top-down” approach, implemented by central authorities and structures. What is missed in this vision is a fundamental element: a ‘user-centered’ or rather ‘people-centered’ perspective, both in the general approach and in the definition of concrete operational strategies.

In general, it is now a shared opinion that actions for the development of territories are more effective and equitable if they involve and stimulate communities, both local and global, with appropriate paths and tools.

However, precisely because the purpose of tourism promotion is intertwined with the need to activate re-appropriation of identity processes by residents in Albania, the ‘people-centered’ approach represents the natural declination of any program, thus becoming mandatory. It is necessary to create the significance for residents and re-distribute benefits (beyond revenues) among them, with inclusive and extended processes. The strategy, however, though mentioning the importance of the resident market for the Albanian culture, reserves in the text to dedicate a separate approach for this purpose for the future.

Signs of “top-down” processes may also be encountered in several points of the document. Firstly, the communication of information—extensively recognized as inadequate—takes the form of unidirectional ‘delivery’ by the central structures to the ‘mass’ of consumers of it; in this way, the fundamental principle of the value of shared information is being ignored, reserving the role of information dispenser to central structures:

It mentions exclusively a central website and, in general, governmental websites or agencies for the construction and circulation of heritage knowledge;

The role of tourist guide is rigidly conceived as an absolute keeper of all knowledge on heritage and the only one entitled to communicate its value to visitors [

2], denying the possibility of contact and integration with dynamics that involve users and the possibility of widespread participation in the creation of value or content;

The definition of thematic paths, of which, anyway, the multifaceted cultural and economic utility is lucidly understood, once again is strict (number and themes of itineraries are fixed), without considering neither the possibility of contributions from the bottom, capable of enriching these potentials, nor the possibility to rely on computer technologies that can support it (social media or anything else).

More generally, the decentralization, described as necessary and unavoidable [

9], is not yet put into practice in the official position.

Looking at this signs, it can be argued that, in general, the underlying attitude in this document is one that does not acknowledge an active role to heritage ‘consumers’ or potential visitors; central bodies seem determinate to maintain close within their own sphere and competencies decisions and in general the possibility to impress directions to processes related to heritage and tourism development. What, on the contrary, can be deduced from the analysis of available literature is a general feeling of scarce interest from the part of government in sustainable promotion of heritage also for tourism purposes and a limited understanding of its importance. More specifically, the literatures ranges from judgments of plain inertia [

19], to insufficient competences [

6], up to direct responsibilities for heritage losses and environmental damaging or even corruption [

5].

At a more practical level, in terms of ‘what is happening in Albania’, the facts related to a number of destroyed or endangered castles (Shkodra, Durres, Preza, Kruja, Elbasan, Bashtova) and to the—temporarily suspended—project of transformation of the Lezhe castle in a luxury resort with tennis court are, in a way, symptomatic. Other events are, on the other hand, encouraging signs, such as the recent creation of the Albanian Heritage Centre aimed at the information of the general public on heritage-related issues [

19], or the experience of balanced revitalization of the unknown village of Nivica (a little, largely abandoned community in a remote inland area, ruled by ancient agricultural and farming lifestyles), achieved by inhabitants themselves [

20], in line with the so-called ‘social responsible heritage management’ concept [

21] and with the need to connect heritage life-cycle with real communities theorized by Turpenny [

22].

At any rate, inertia, at least, comes into play with reference to unresolved problems of property issues having a role in the processes of illegal land occupation and convulse construction of houses and other buildings [

23] and to the failure of legislation in force in repressing damaging and vandalism phenomena [

17]. The awareness of the need for a legislative reform and for a more effective action from the part of governments is rather diffused.

2.4. The Principles

Precisely because the experience-based value of the visit is central to the textual formulation of the national strategy, it is not possible to leave aside the importance of individual impressions, which obviously are not uniquely foreseeable, but produce absolutely original and personal effects, although the strategy appears to have absolute trust in the possibility of determining a priori the impression that the visit will produce. This results in the need, at the operational level, for tools that adequately take into account this important contribution and support its explication.

Sustainable development of tourism is mentioned in all strategies, but only in theory; the only supported dimension is, in fact, that of economic growth:

As stated by Sharpley, “tourism is primarily a social activity” [

24] but the possibility of contributing to social cohesion, to the synergic relationship between residents and tourists, to the creation of a greater attention to the available resources through the sense of belonging, is not cited or in any case not sufficiently deepened;

While identifying the upper middle class of North America and Europe as the target for the promotion strategies, and although aware of the gap, compared to it, at the level of service standards, there is no trace of strategies or timelines for the introduction, for example, of certification of services’ environmental performance or simply good practices;

The attention to specific aspects of environmental impacts reduction is absolutely limited and there are not specific initiatives or thematic sub-objectives. It is hoped that the growth of the country’s image in relation to its economic strategy will address at least those of greater visual or experiential evidence, given the landscape nature of the most important assets. Waste disposal and preservation of clean water are considered, in fact, as ‘major concerns’, but in the perspective of the alignment with Europe and the international market, it is not enough. For the same reason, it is also not sufficient the sole reduction of upstream impacts (synthesized in the expressed objective of tourist flows de-seasoning).

2.5. The Action Tools

The strategy clearly identifies the limits of the equipment for the tourism promotion in the current state:

The reference website “

www.albaniantourism.com” does not provide indications on how to reach single sites or other practical information;

Many existing products for image communication are not widespread because they are reserved for VIP users, instead of being profitable on the market; the same thing happens for events that can attract a vast public, communicated only on site and, thus, only available for actual tourists; which can be explained only partially by undeniable budget issues;

Even the management of events or opportunities to attract the attention of foreign media to the country has proved to be inefficient and not very promising.

However:

The need for websites, guides and gadgets is just quoted in a non-priority way, as ‘lesson learned’ by other case studies but not adequately addressed;

It does not address the need for concrete tools, customizable by users, but a massive ‘government-to-government’ communication action is prioritized; the communication strategy seems to be interpreted as an action to an undivided mass and not to a plurality of individuals;

The ‘word-of-mouth’ power is mentioned, but the means to exploit broadly this channel are not taken into account;

The contribution that communication technologies can offer is not taken into account concretely; usefulness and need for tools are not included and investments, considered strategic in consultancy and skills, are limited to the marketing strategies sector and are not aimed at understanding the opportunities offered by ICT.

In order to bring the development of the tourism sector within the ideal borders of sustainability—not only in economic terms but also in environmental and social ones—the individuals’ centrality must therefore be assured even in the phases that follow the definition of any promotion strategy. This has to be realized by developing tools that take into account the variability of the processes with which the potential visitor defines points of interest, times and modes of visit, personal thematic or geographic paths, thus appropriating a long unknown heritage and establishing personal ties with it.

3. Sustainable Smart Tourism and Mobile Applications

In recent years, tourism has become “one of the strongest drivers of world trade and prosperity”, and this important developing sector contributes 5% of the world’s GDP [

25].

Moreover, globalization and continuous changes of environmental conditions determine the need of an uninterrupted innovation to improve the competitive ability [

26] of tourism destination in a smart vision.

Tourism plays, in fact, a key role both in “inclusive and sustainable economic growth” and “sustainable consumption and production” due to the potential impacts in the growing of destination and communities, preserving local resources [

27].

For instance, the question of travel and transport influences greatly the sustainability of tourism, because they have environmental impacts at local and global level. In fact, they could threaten the local ecosystems through, for example, pollution and conversion of lands [

28]. Moreover, other problems such as degrading of natural resources, vegetation structure and habitat, increasing deforestation and decreasing upstream water flows, can be caused by mass tourism [

29].

For this reason, the idea of Ecotourism, which firstly regards ecological destinations, but is easily extensible to other contexts, involves much research focusing, among other things, on the need to minimize impacts and to promote environmental and cultural respect and awareness.

In this context, the mobile applications and all the tourism technologies concur to the development of the so-called “smart tourism”.

In general, it is possible to talk about this only when the interconnection between communities and destinations is achieved thanks to dynamic platforms, intensive communication flows and enhanced decision support systems [

30,

31].

Therefore, it is derived from the combination of expanded tourist knowledge and improved decision quality with the use of IT devices. According to Chung et al. [

32] information and communication technologies represent a possibility to grow because they link the creativity with an economic activity, creating the so-called “creative economy” [

33].

The concept of smart tourism goes beyond “e-tourism” [

34], intended as a simple providing of information, because it focuses on the idea of support in the decision process and on the role of three great areas: tourism experience, business ecosystem and destination [

35].

In particular, Del Chiappa et al. (2015) [

36] defined a tourism destination as a “networked system of stakeholders delivering services to tourists, complemented by a technological infrastructure aimed at creating a digital environment which supports cooperation, knowledge sharing and open innovation”.

In this context, the market of the mobile apps has become relevant thanks to the growing use of smartphones and, in particular, travel apps are the seventh most downloaded typologies [

37].

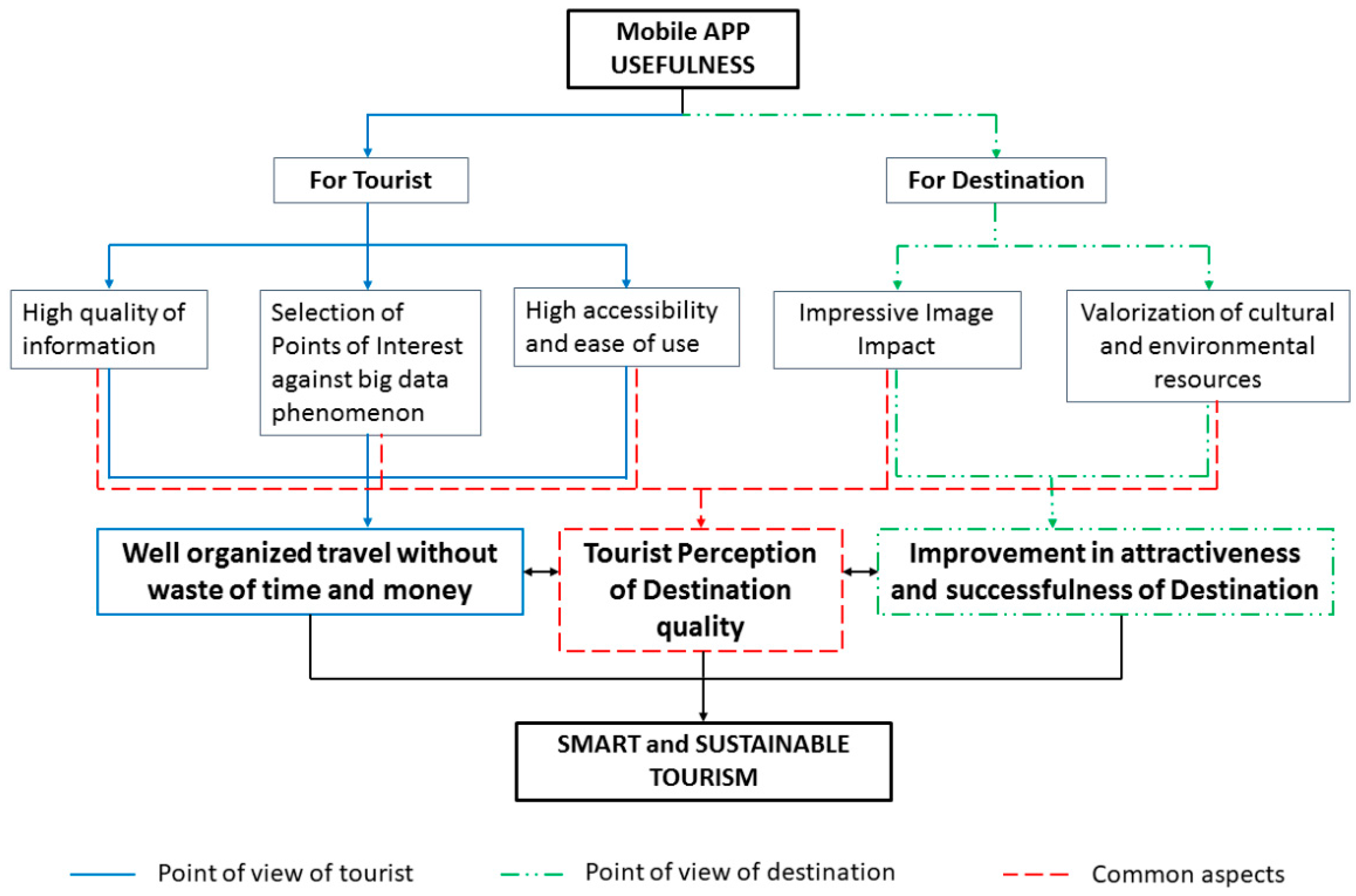

The usefulness of tourism mobile apps can be classified according two points of view: for the tourist and for the destination (

Figure 2).

In the point of view of the tourist, the use of a technological platform can implement not only his knowledge of the destination but also can direct the great flow of available data in a smart way for all the stakeholders that include entrepreneurs, tourists, local people, public administration.

The Internet is easily accessible for all these users and influences their decisions. The spread of smartphone technologies has given new opportunities and has shifted the focus of information research from the primary needs, such as flights and lodging, to cultural and environmental description of the site, travel experiences and other tourists’ opinions [

38].

However, the “big data” phenomenon implies the huge amount of information in the actual dimension of tourism.

On the one hand, it represents an opportunity to link a series of products and services according to tourists’ needs and expectation [

30]. The strength of ICTs, the Internet of Things and Cloud Computing is properly the accessibility of the information in every place and to most of people in the world. It allows for delving into the characteristics of the tourist site and planning every activity and visiting without wasting time and money. In fact, travel planning involves a series of activities such as idea formation, searching for information, taking decision, booking, visiting, with an iterative complex process influenced more and more by the smart tourism technologies [

39]. The tourist builds his experience learning, reading up and visiting places.

On the other hand, the development of social networks, tourism websites and the massive archive of travel blogs, in which a continuous exchange of opinions and information occurs [

28], can lead their users to confusion and uncertainty [

40]. In fact, technology enables people with various levels of involvement in tourism field to program their travel, but the selection of suitable data in the so-called “information overload” [

41] depends on their different level of knowledge and experience.

In this context, mobile apps can support the tourist to make their travel sustainable and effective, summarizing urban travel information, selecting their own points of interest and avoiding the problem of sparsity of data.

Tourists are active participants in the aforementioned “creative economy”: the people’s desire to discover new places, to change their daily life and to broaden their knowledge has turned digital media in machine-driven decision and planning tools.

In this context, the smart tourism technologies facilitate tourist information and decision-making through some fundamental characteristics: information quality, source credibility, interactivity and accessibility, besides “self-efficacy” that is the tourists’ ability and skills of using them to make travel plan and decisions [

42].

In the point of view of the destination, tourism development is extremely linked to the attractiveness of the site and to the value of cultural, historical and natural environment.

In the galaxy of mobile tools, used for the most different objectives, they can be the way to understand and to increase the values of whole cities and their cultural heritage, saving the intrinsic historical significance of architectures and surrounding context and improving regional economic systems.

In particular, the cultural tourism is characterized by “low volume—high yeld” [

32] and tourism mobile apps, providing complete land and infrastructures description, can become the intermediate channel to spread and valorize cultural and environmental resources of the visited site.

Finally, they can improve the image impact of the destination that influences tourist impressions and decision-making process, increasing successfulness of the site.

From all of these considerations, it could be possible increase the tourist perception of the destination quality, linking the two aspects described here and achieving the improvement of the touristic activity in a smart and sustainable way.

4. Tourism-Related Apps for the Albanian Context: A Taxonomy

In general, applications are categorized (ranking) on the most popular and main “stores” based on their purpose or a series of end users’ evaluations and reviews. In the study of requirements for the software development of the SOS-Tirana app and the analysis of any best practices, it was assumed to focus on the most popular and well-known store for Android applications, the “Play Store”. The research was carried out on the store using the search keys [Albania] + [tourism] and [Tirana] + [tourism] (“tourism” as an alternative to “travel”) and all applications were analyzed and installed, including also the ones that are less relevant and poorly positioned in search results. In the results, guides such as “Europe Travel Guide” or “Trip Advisor” were omitted because these apps are available in almost every city or country, differing only in content. The total number of analyzed apps is 22, although 20 are diversified, while two of them are advertised under a different name on the store but are the same apps (

Table 1). The conceptual model, used in order to understand differences and similarities between mobile apps classified in the tourism field of the City of Tirana and of Albania, is deductible from the taxonomy of Kennedy–Eden and Gretzel [

37]. This taxonomy divides the various types of applications available on the market from two points of view: a taxonomy based on services that the apps provide to the user and a taxonomy based on the level of interactivity that the user has with the mobile application.

After an initial analysis phase, it was considered to focus more on taxonomy based on the services offered by the apps, in order to characterize better the gaps in the panorama of mobile apps and related to the Albanian tourism sector. The aim was to articulate the analysis of the state of art of the Albanian mobile market, answering a specific question: “Why do you have to use the application?”

In analyzing the 20 apps, the seven categories defined and used were Navigation, Social, Mobile Marketing, Security/Emergency, Transactional, Entertainment, and Information (

Table 1).

The analysis of tourism apps on the Albanian towns shows the sole availability, at the moment, of technologies distributing basic information to users: from the nearest first-aid station to doctors’ offices, up to the closest POS-ATM point for cash withdrawal or parking meter. It is more than evident, then, that the technological offer has been focusing on primary exigencies of tourists; but undertaking a journey can involve a considerable impact in many respects.

In such a context, the selection of transport means or the choice of accommodation facility are important decisions for the tourist, that are currently supported through a huge flow of available data on the whole region and usable in an intelligent way from the part of tourists.

Nevertheless, dealing with the topic of cultural heritage valorisation and tourism promotion through apps requires some premises. The integration on the territory, of a number of technologies supporting tourism or heritage fruition is not a simple task. If it were so, the devices would not be missing or would be easy to implement by now: QRcode, free Wi-Fi, augmented reality, dedicated apps and much more. But how are these tools to be obtained?

In general, a community with a strong sense of identity, aware of its heritage, becomes the natural testimonial of its own territory, also with the help of new technologies. Virtual places such as Facebook and blogs spread information and are the virtual places where people can exchange suggestions, comment posts, share photos, be pro-active. In this respect, if a smartphone is added to the picture, allowing users to share their position, images and videos in real-time through an app, the “word-of-mouth” mechanism is activated, which is still one of the most powerful marketing tools in the tourism sector. The SOS-Tirana app has good potentialities, in the current scenario, to perform effectively in support of awareness-raising, participation and content-building processes useful for the improvement of the destination’s image and services and, ultimately, of tourist hospitality; especially in a community, such as the Albanian one, with low sense of identity and limited awareness of the heritage. As a matter of fact, from the survey on apps for Albanian towns it emerges that only 50% (11 out of 22 apps) describes cultural sites, mainly qualifying them as “attractions” rather than as “cultural or environmental heritage” assets. The consequences are evident, ranging from unconcern towards cultural heritage to the poor understanding of policies for territorial promotion, up to the inability to answer information searches from the part of an “intelligent” tourist.

Furthermore, the “Tirana Ime” app is the only concrete example of a participated app for urban order or tourism site accessibility, allowing users to report problems or service malfunctioning and suggest improvements.

Most apps are mere tourism smartcards (“Tirana map”, “Albania City Guide”, “Travel in Albania”), that have networked basic descriptions of cultural assets and services with the main purpose of collecting information on the movements and preferences of tourists. Such data could surely be functional to the improvement of the tourism offer; at any rate, within the technological offer, the attention of businesses, far from having the goal to make collected information available to the public, is more than evident.

Among the surveyed apps, the use of social media and accounts is to be reported, based on logics that are mainly unidirectional and strictly top-down, where tourists’ presence and attention are not opportunities for ‘listening’ and participation, but simply receivers of news and announcements, more or less suited for the tool. In the current scenario, where tourists want to be more and more co-producers in the planning of visits, this picture is far from what could be done today to match the tourism offer.

5. The Design Phase: Steps, Problems and Solutions Adopted

The primary objective of the research project was to realize a process of “active” knowledge of the visitor, who, in the game of real-time knowledge of his geographical position and to each change of the context and interaction, is able to identify in a short time new contents with an identity value, with the support of the SOS-Tirana app.

Within tourism, as with other areas of life, smartphone apps have the capacity to reshape dimensions of social life, including travel [

43].

The expectation was not just to consider a “beautiful landscape” and enhance it as if the technological tool were a “postcard” or a similar technological medium (sharing social networks, shared selfies, etc.). The objective was to use an innovative technological tool, functional to the construction of a relational system and able to restore meaning and value to the identity structure of the community, creating a strong and new sense of identity.

The analysis takes a relational view in which smartphones, as socio-technical devices, are transforming how we engage with place [

44].

This electronic age has wrought profound changes on how we think about and experience who we are, where we are, and how we relate with one another. Wilken’s study re-evaluates how ideas of place and community intersect with and help us make sense of a world transformed by information and communication technologies, exploring approaches from media and communications, architectural history and theory, philosophy, sociology, geography, literature, and urban design. Thus, the initial assumption was that of considering and underlining that the tourist visiting does not benefit only from exclusively dedicated services, but shares, with the resident citizen, a whole reality and, with that, a series of services or disservices (mobility, environmental protection, accessibility).

Therefore, from the design phase, the research project has aimed at the discovery of local communities, even unknown communities, and the enhancement of their own heritage, defined as “the heritage of all”. The project was an opportunity in which technologies and human skills met creatively, thus triggering a process in which the local community became a driver of innovation, representing a valid starting point, with a view to activating a virtuous circuit of bottom-up processes, highly inclusive and enabling, and contributing to the innovation of the market of available technological solutions.

The software architecture of the app was designed on the primary requirement to create an innovative fruition model that could allow, at “zero cost”, the expansion of access to content, context data, settings, user-visitor customizations, additional information and explorations; including through the use and integration of new technologies (VR-Virtual Tour) and new forms of communication (digital storytelling).

The ambition was to transform cultural fruition into an “event”, making the moment of fruition easy and attractive, “smart”. Digital VR technology stimulates the enrichment of human sensory perception through the presentation of (virtual) contents and information; this technology is therefore able to increase what the observer perceives with his senses, as the subject immersed in an environment, enriched with virtual objects and with which the user can interact.

Unlike a web site, it is not possible to access a native app through a URL, but the app, after downloading it from an app store, such as those provided by Apple, Android or Microsoft, must be installed on your device. The user, after installing the app, can access the functions of the application and use the specific device hardware (the digital camera, accelerometer, etc.), or even more simply display the content of the app, similar to a web-app.

A native app is compiled binary code for a specific device and often offers more consistent approaches than those that browsers are capable of offering.

Native apps can offer a wider range of features, very similar to a Microsoft Windows application, if compared, for example, to a web site displayed in Internet Explorer.

A native app, when compared to a responsive web application, can provide: highly robust design and user-friendly interfaces, enhanced interaction with the device’s file system, native interaction with devices and specific features of a smartphone or tablet, and the possibility to use the application even when the device is not connected to a network, as well as greater security performance.

Currently quite complex applications, functionally and visually, see in the native app the best choice for their implementation. Excellent framework and SDK make building this type of application relatively simple compared to the design and development of responsive applications.

The technical motivations, which determined the choice to adopt Android rather than Apple’s iOS as operating system, are essentially:

The adoption of custom Launcher (launch icon): In an Android platform, we can modify the launcher and design the interface of the home and menus according to the specific needs;

The use of widgets: one of the functions preferred by users are widgets that with the adoption of Android can be placed on the home screen and therefore have small applications always in operation and on the main screen;

The use of Adobe Flash Player: Apple chose to exclude the Flash Player from its devices, and this limitation was too restrictive for the architecture of the app to be designed;

The possibility of integration between applications: Android allows developers to make real-time additions between applications, more than iOS currently.

Gathering and agreeing on requirements is fundamental to a successful project; ITC and IMK analyzed the end user’s needs and elaborated detailed requirements for the functionality and look-and-feel. Our approach to app design rests on following aspects:

Planning every user interaction with the software to make it convenient and easy to follow;

Providing mockups and welcoming feedback to visualize the End User’s ideal application and app;

Designing and bringing fresh ideas for visually mobile apps;

Designing an environment Integrating Virtual Reality to expand mobile user horizons and offer new perspectives;

Designing and developing a platform that includes robust exchange tools intended for solving a variety of tasks, such as support of geographically distributed info-bases (JSON data exchange format) or building complex heterogeneous information systems.

The team emphasizes careful planning and architecture design to advise on better technological options with respect to the innovative tourism industry.

To simplify the publication of geo-referenced information, the app will store all the data in a Geographic JavaScript Object Notation (GeoJSON) file rather than in a database. In 2015, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), in conjunction with the original specification authors, formed a GeoJSON WG to standardize GeoJSON. RFC 7946 was published in August 2016 and is the new standard specification of the GeoJSON format, replacing the 2008 GeoJSON specification. Most GeoJSON data consist of objects with multiple properties, then with complex and structured data, so we need to determine whether the data is valid or not. We will adopt a standard GeoJSON-Schema that will describe the structure and the requirements of the project data.

The lifecycle of mobile development is largely not different than the software development for web or desktop applications. In the ITC approach, there are usually five major portions of the process [

45,

46,

47]:

Inception: All apps start with an idea. That idea is usually refined into a solid basis for an application. More recently, researchers have been observing a paradigm shift in tourism consumers, who are becoming prosumers and co-creators of their experiences. A prosumer is a person who consumes and produces “media”, so, for example, with potential to connect through mobile phone apps and other location-based devices, we could encourage guests to upload their own stories or experiences to social media accounts and help us build a map together.

Design: The design phase consists of defining the app’s user experience (such as what the general layout is, how it works, etc.), as well as turning that user experience into a proper user interface (UI) design (mockup deliverable). When creating mockups, it is important to consider the interface guidelines for the various platforms (Apple, Android, Windows Phone) that the app will target.

Development: Usually the most resource intensive phase, this is the actual building of the application.

Stabilization: When development is far enough along, QA ITC specialists usually begins to test the application and bugs are fixed. We presume, however, that the app will go into a limited beta phase in which a wider user audience is given a chance to use it and provide feedback and inform changes.

Deployment.

Once the app has been stabilized, it is time to generate a release build of our app, targeted at each platform we wish to deploy on. There are a number of different distribution options, depending on the platform.

6. The SOS-Tirana App

The mobile app for Tirana is organized into three sections (

Figure 3): ‘List of PoI’, ‘Search’ and ‘Map’ (with overview and three display modes—hybrid, streets, and satellite).

All the three sections contain on the top the ‘Action Bar’ (AB), containing three areas:

The first is located on the left and contains the logo and title.

The second is located in the middle and contains an action button ‘Map’ that opens a view that handles the display of interactive map with zoom extension.

The third is located on right and contains an action button that runs a several actions of the app and updates according to the current view.

After launching the app, the start page is opened for few seconds, allowing the automatically updating of the contents published on the server if modified. Then, the app offers the user the “PoI List”, a scrollable list containing all the points of interest, grouped by typologies, such as castle, bridge and so on. Next to the heading of each typology, there is a button with a down arrow to allow the user exploding the list (under the heading of the chosen typology) and viewing, below, the list of PoI’s selected typology. Through this list, the user can access specific information of the various PoIs, proposed and grouped according to the different types. Selecting the item relative to a PoI within the scrollable list, the user access another scrolling list named ‘list of Media’ containing links to media content available for the selected PoI. The use of scrolling lists makes information access much more intuitive and faster; these views, in fact, are optimized for touchscreen mode. The scrollable ‘List of Media’, allows the user to:

Display on the device the map centered on the PoI (‘To PoI on Map’);

View the information sheet of the selected PoI (‘To About PoI’);

View the virtual tour of the selected PoI, if any (‘Virtual tour’).

Selecting the item ‘To About PoI’, the App opens a view that contains a detailed information sheet of the selected PoI and reported on three pages, which are available by sliding finger across the screen horizontally. The three dots, at the bottom, indicate to the user in which of the three pages he/she is.

The ‘Search’ section, often absent in other systems, has a friendly interface based on a dialog box containing:

A ‘Search’ textbox; typing a letter in the textbox, an interactive list of PoIs containing that text is automatically generated.

A back button opening the former screen.

A ‘search results list’ showing the list of PoIs complying with the search criterions; thumbnail, title and short description are reported.

In the ‘Map’ section, the user interact with the Google maps in traditional modalities:

Navigating with ‘pan’ and ‘zoom’ tools, the user can view more detailed elements of the map; furthermore the user, clicking the grey button on the top right corner of the map, centers the map on his/her location, viewing PoIs nearby.

Clicking the markers, the user open the previously designed ‘callout’ reporting info about the selected PoI (thumbnail with link to the photo, title, description) in a popup window above the map, at the specific location.

A ‘cluster marker’ has been introduced: if several PoIs are close, they overlap when the user zoom in the map with a loss of information. Beyond a predefined threshold, the overlapped markers are temporarily replaced with a cluster marker.

7. Discussion

The Albanian scene, torn between tourism development and the safeguarding of congested territories, seems to be reproducing the long-lasting conceptual dichotomy between economic growth and sustainable development. On the one hand, it cannot be denied that, as these are rather new themes for this country [

17], the need to rely on a robust theoretical framework, more than on new skills or competences, is fundamental. Unfortunately, it must be observed that, within the specific field that form the scope of this article—mobile apps for tourism-purposed promotion of cultural heritage—many concepts come into play and overlap which have in common a widely acknowledged ‘under-theorization’.

‘Cultural’ heritage and ‘total’ heritage: from the literature, a growing interest and an increasingly animated debate on issues of cultural heritage can be deduced. In recent years, the number of ‘stakeholders’ or ‘actors’ having some form of interest in heritage has progressively increased. This has produced, on the one hand, the proliferation of studies on heritage, which has not given life to a shared reference framework [

48]. Moreover, it can be added that the growing ‘collective’ character of the concept of heritage (in relation to both what can be defined as such and who has legitimate interest in it or is affected through or entitled to specific relations to it), by introducing a plurality of interpretations and points of view and increasing the subjectivity of definitions, has in fact made the picture rather unclear [

49]. Then, the ‘cultural heritage’ concept is quite controversial; the characters of cultural heritage that emerge most clearly or frequently can be identified, mainly, in the duplicity of the value attached to it, at the same time cultural and economic (which originates the ultimate problem of conciliating development and preservation), ‘elasticity’ (in relation to its more or less restrictive definitions), ‘dinamicity’ (since it is produced over time by people and societies) and ‘dissonance’ (in relation to the coexistence of different uses and consumption forms). In any case, the growing multiplicity and democratization of the ‘heritage’ concept is identified in the literature as being the cause of two fundamental evolutions [

48].

The first one is related to the widening of what can be considered as ‘heritage’, up to, virtually, all of what represents a tangible or intangible expression of the way of life and of the culture of a people, a community or a group in a certain moment in time.

The second evolution is the gradual distancing from the traditional vision focusing on intrinsic—and then absolute—characters of cultural resources, in favor of one centered on people, on their needs and on the functions accomplished by heritage, which are ever-changing and then contemporary. At the level of action strategies, this evolution reproduces itself in the shift from heritage ‘preservation’ (the care for its physical integrity) to its use in a ‘functional’ sense (changing with time) and sustainable (in order to assure its ability to accomplish functions, even if different, for future generations). The link between the concept of heritage and the concept of sustainable development is another important trend that can be read in literature [

14,

48,

50] and its explication through efforts to conciliate resource conservation and territorial development through their use and the search for a balance of environmental, economic and social dimensions, leads to define cultural heritage as integral part of the whole environment, indissolubly linked to the natural and socio-economic elements.

As a consequence, the concept of ‘total heritage’ put at the basis of the official Albanian policy for the tourism-purposed promotion of heritage surely finds its legitimation, at the theoretical level, and a consistent application in the goal of defining a variegated cultural tourism offer.

At any rate, the outcome of the theoretical dispute, well explained by Loulanski [

48], between ‘object-centrists’ (a resource has value in itself and its preservation is in its own interest) and ‘functionalists’ (a resource has ever-changing values, attached to it by people, and its preservation is in their interest) represents a lost match for the official ‘top-down’ policy and reliance on predetermined values of heritage. It is about absolute, objective value vs. the ‘continued re-endorsement of value by use’ [

51] and the reading of heritage as ‘life values’ [

52]. In this controversy, as a matter of fact, the ‘object-centric’ position gives way against the necessity to rely on criteria for the definition of priorities in preservation interventions on heritage; criteria that are necessarily subjective, as they are formulated by people in different time periods: nothing absolute and objective. It is then evident that the participation of heritage ‘users’ or ‘consumers’ in bottom-up processes is unavoidable and must be adequately accounted for both in policies and in the delivery of instrumental support to them. The analysis presented in the first part of the article shows that the official position of the Albanian central government seems, at the moment, still far from this perspective.

Transferring these reflections to a different disciplinary area, we can affirm that the evolution of the concept of heritage, from “cultural” to “total” (more ‘people-centered’) and to a dominant experiential component, embodies, in the marketing field, the so-called ‘shift’ from GD-Logic to SD-Logic (i.e., from a logic dominated by goods, in which the consumer is external to the creation of value, to the logic dominated by services, in which the value emerges during use and is co-created), analyzed by Bick et al. [

53] in the field of mobile technologies.

There are certainly similarities between this transition of the productive sector and the heritage sector. In the GD-logic, as in a top-down process of defining the value of a cultural good, the ‘consumer’ is outside the production of that value, while in the SD-Logic services correspond to experience, in which the value is created in the use phase and the creation is strongly dependent on consumer participation. On this basis, we can therefore try to apply to the visit experience the Holbrook model [

54], developed for the marketing sector and focused on the definition of ‘customer value’, as an interactive and relativistic preference experience, in which the value is comparative, situational and personal.

This is already sufficient to make it clear that the assumption of being able to define a priori reactions and therefore classify visitors into homogeneous groups based on behavior and attitude towards the heritage is not plausible. Moreover, individual skills and knowledge (and therefore the ability to technically relate with the heritage and know how to ‘read’ it) are added to the comparative, situational and personal variables, reinforcing this impossibility.

This confluence of principles and concepts, that are all insufficiently supported by an organic theoretical framework in the specific tourism sector, makes the Albanian task more difficult, adding also to the need to fill a critical gap in terms of concrete support instruments and in particular of ICTs.

In fact, even this latter phenomenon does not have an organic basis of reference in literature; many studies analyze digital divide (DD) effects on various economic sectors but very few of them focus on tourism, although information is the lifeblood for this sector [

55,

56]. Many researchers have explored and explained the different ways in which the disparities in the technology sector are realized, highlighting the existence of different connotations: International/global vs. domestic/social DD [

57], possess-related vs. use-related DD and second-level or horizontal DD [

58]. In Albania, committed to redirecting touristic flows to the most internal areas, the problem is amplified exponentially, since the global component (Albania vs. world) is added to the social one (coastal zones vs. inland areas) and both coexist with the horizontal DD.

Adopting the Minghetti and Buhalis integrated model [

56], it is important to keep in mind, in particular, that low-accessibility destinations are more dependent on external intermediaries to promote their offers on the market. These intermediaries will presumably impose high fees and unfavorable trade conditions. This leads to an unequal distribution of the wealth created with tourism. The risk for the tourism sector is, as pointed out by Maurer and Lutz [

59] to make the development even more ‘asymmetric’ (in other words, unbalanced).

It is also to be noted that even the Albanians themselves do not know some places that instead represent exceptional cultural resources, as in the examples of the village of Nivica [

20] and the ‘militarized’ island of Sazan, with its net of trenches and bunkers, which has long remained ‘mysterious’ to Albanians [

60]. This is therefore a relationship between a ‘low-access’ destination and ‘low-access’ visitors; having to ‘communicate’ a destination not only to foreign tourists but also to residents themselves, ICTs should be carefully identified and implemented (and also integrated into a system that should not abandon traditional forms of communication, using multiple channels).

Many researches have evidenced that the only availability of hardware and internet access do not solve digital divide [

56,

61,

62]; skills and competences are necessary that can only be assured through collaboration with more developed countries and international institutions, providing an effective solution, albeit in the medium to long term.

Our aim is to contribute to reducing this gap at the operational level, showing how it is possible to support concretely principles such as those listed above: the experience of total heritage, and the creation of a customized relationship with it; the independence before, during and after the visit; the balanced development of the territories. This can be obtained through the development of easy-to-use tools, then highly inclusive and able to facilitate autonomy and customization, which can strengthen the visit experience and at the same time contribute to sustainable development of the tourism sector, informing visitors about unknown resources and places that deserve the same attention as the overcrowded coastal areas.

In general, tourism can contribute to the fulfilment of all the three dimensions of sustainability [

63] in the development of the Albanian territory:

Environmental: if properly managed, it can facilitate, through the re-directing and reduction of flows and through de-seasoning, the mitigation of the impacts deriving from intensive pressure on congested coastal areas;

Economic: the integration of marginalized inland areas in the visitation routes allows for their integration in the country’s productive system and the increase of incomes;

Social: the promotion, for tourism purposes, of less known resources together with more famous ones acts as a stimulus to the re-appropriation and re-evaluation from the part of residents, enriching their perception of the cultural identity.

Due to their enlarged fruition potential, apps amplify these effects exponentially, much more than any communication or marketing strategy; in the specific Albanian context, the two-fold objective of tourism growth and awareness raising about the country’s image among citizens and abroad needs to be supported through instruments in line with this perspective. The SOS-Tirana App is consistent with this vision; since it is available, by its nature, both to tourists and to citizens, it constitutes a common ground for the sharing, exchange and dialogue between tourists and residents. The tools designed and the information that it delivers to users promote the creation of resource significance from the part of visitors, since they strongly enable to the creation of absolutely ad-hoc, customizable itineraries. The importance of visit itineraries, anyway, has been well understood within the national strategy, in their potential to contribute to the creation of destination identity, broaden the geographic provenience of visitors, intercepting them through affinities in interests and preferences and increase the duration of stay, with positive effects on incomes in the last two cases.

Nevertheless, it appears more appropriate, in this respect, to look at users not as a ‘shapeless mass’ with univocal and predictable behaviours and needs but rather as a complex of different individualities with diverse exigencies.

As for technical features, the SOS-Tirana App is, at its current state, extremely innovative, if regarded as technological platform for the knowledge and valorisation of sites with cultural and environmental interest, within the local context.

In contrast with the 22 surveyed apps, the SOS-Tirana app is the only one offering both tourists and destinations

High-quality information;

An accurate selection of cultural points of interest;

Ease of use of maps and access to information;

High-quality image gallery;

High-quality virtual tours with strong visual impact, from single 360°-panoramic objects to navigable virtual tours with maps, guide texts and navigation points (hot points).

In this way, it can match the requisites identified in the national strategy, particularly those related to access, ‘impressive’ capacity and engaging power, exerting a strong appeal on potential visitors.

It must not be forgotten than tourists on a visit do not just enjoy dedicated or thematic services, but also share, with resident citizens, a complex reality and the respective system of services or disruptions (mobility, environmental protection, accessibility).

The current strategy identifies specific criticalities with respect to the quality levels of infrastructures and accommodation services. Furthermore, decision-makers largely rely on a sort of ‘tolerance’ from the part of ‘pioneer’ tourists, engaged in the discovery of an unknown Albania and its ‘total heritage’, towards shortcomings in those aspects. Actually, on the one hand, such indulgent attitude cannot be assumed to represent a whole community of visitors that, as widely recognizable, are more and more exigent, informed and well-aware of their rights and of what other destinations can offer. But, above all, that approach is a short-lasting one, ‘paying’ as long as a destination is ‘unknown’, and it does not loyalize—after the first stay—either those tourists of the ‘unknown’ or the ones seeking comfort and quality. Once Albania is definitely established as a destination—and that is not far off—investments must have been made by the government, by then, to amend those flaws in order to meet wider and wider tourist groups’ expectations. It must also be added that ‘word-of-mouth’, even from ‘forgiving’ consumers, can see the weight of the ‘wow’ effect faded against whatever else is experienced, if taking place in an even slightly delayed ‘post-visit’ moment of time. In other words, word-of-mouth can turn detrimental anyway; and it is certainly perceived as more trustworthy than other sources since people posting impressions and opinions have generally no material interest in recommending or deploring a destination. As a consequence, apps supporting those interaction channel are extremely powerful in promoting or scathing processes that only pay lip service to good intentions, since incredibly ‘faster’, in their communication dynamics, than any other too ‘self-confident’ human process tending to put off addressing problems, especially those already recognized.

The context itself, then, suggests that we should not overlook, but rather rely strongly on the cross force of citizens’ participation and on the activation of bottom-up processes. In the depicted scenario, ICTs can play a crucial role for the growth of the Albanian tourism sector; if properly exploited, they can realize a unique synergy with the country’s extraordinary potential.

As already mentioned, the digital divide across some wide user groups (among both tourists and residents), coupled with the lack of adequate skills also among the staff involved in heritage management [

5], requires a huge effort for the setting up of user-friendly tools that bring information within reach of as many users as possible, and that cannot be solved exclusively from within the country. Nevertheless, it is possible and important to capitalize the experiences gained within the long-standing cooperation between the country and the other entities of the Mediterranean basin in the field of ICTs, concretised in different EU programs. The SOS-Tirana app is the result of a joint project of the Construction Technologies Institute—National Research Council of Italy (ITC-CNR, Bari) and the technical staff from the Instituti i Monumenteve te Kulture (Tirana) [

64,

65]. Since its conception, the project aimed at the discovering of local communities and to the enhancement of their heritage, meant as “collective heritage”. In this occasion, technologies and human capacities have met in a creative way, activating a process in which the local community has become an innovation carrier. The SOS-Tirana app is, then, an innovative and effective tool supporting the growth of the communities’ sense of identity and connection to their territory.

The suitability of our app is demonstrated through the consistence with other studies in the same field. In particular, it is in line with elements of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) [

66] and with its expansion proposed by Garry Wei-Han Tan et al. [

67] in relation to factors affecting users’ intention to adopt mobile apps for tourism-related product purchase:

Common context-related issues led us to consider the results applicable also to Albania: as in the case of Malaysia, Albania is also an emerging market in the field of mobile technologies [

68]. Furthermore, the importance of mobile for travelers of emerging markets has been clearly stressed and motivated through their dependence on smartphones as main device for the use of the Internet [

69].

In our SOS-Tirana app, effort expectancy (EE) was pursued as a pre-requisite already in the inception stage, starting from results of the national strategy analysis described in the previous paragraphs.

Innovativeness and playfulness were, then, objectives of the subsequent design stage. As for the first, many features make our app innovative in respect to the whole of available solutions, as explained before.

Playfulness has also been given attention while designing our app, in order to support personalised creation of visit itineraries through the possibilities of different search and selection criteria. Playfulness is amplified through the insertion of virtual tours within materials available for cultural resources, also in order to maximize the experiential dimension in the pre-visit phase.

As for the other two factors, we are of the view, on one hand, that social influence, meant in literal sense, is quite far from our objective of supporting individual relationships to, and appropriation of, heritage and, on the other hand, that it involves dynamics that are beyond concrete possibilities to determine significant effects in our specific field. In terms of involvement and communication capabilities, instead, we paid specific attention to main social networks in order to activate word-of-mouth for the conveying of impressions and perceived quality related issues in relation to the visit experience, as well as for possible real-time problem-solving in practical circumstances.

Facilitating conditions, though not explicitly ‘built’, are indirectly assured through maximization of user-friendliness of features, thus making it possible also for very young people and/or users with low IT skills to operate the app functions.

8. Conclusions

The Albanian cultural heritage, and the whole country as a tourist destination, is receiving a growing attention within the international market. The time is ripe to seize this golden opportunity and capitalize on current conditions to de-season visit flows, reducing the related environmental burdens, enlarging the provenience basin of visitors, increasing revenues and improving the country’s perceived image by increasing the residents’ consciousness, in line with current national policies. Nevertheless, the repercussions of a strategy able to adopt a broader vision of tourism as growth factor and recognize ICTs’ full potentiality, already proven in other contexts, can reveal much greater, in terms of development sustainability.

The deservedly proud Albanian community [

5,

8,

14,

48] cannot risk seeing the goals and strategies of its policy of rebirth through tourism activities fail by overlooking a crucial element such as the individual dimension of the users’ basin. Therefore, practical tools are needed which are able to support, for example, the diversity of interests and of access and fruition modes as well as the creation of original and not predefined visit itineraries, enriching information with the contribution of previous visitors (the only ones that can offer and circulate the ‘experiential’ content mentioned by strategies and activate that ‘word-of-mouth’ formally considered within program documents). Such tools, since they are available to all—and also to residents—allow the starting of processes of heritage re-appropriation from the part of the local community and arouse a careful attitude towards the conservation of cultural assets and their surrounding natural and built environment.