Community Participation, Natural Resource Management and the Creation of Innovative Tourism Products: Evidence from Italian Networks of Reserves in the Alps

Abstract

1. Introduction

- tourists require satisfying, stimulating, high quality holiday experiences;

- private operators (tourist businesses and organizations) are looking for good returns on their investments, and need to make a living;

- public institutions and organizations;

- local residents, whose needs are social, professional and related to quality of life.

- physical controls in the form of barriers, paths, boardwalks, and the location of facilities used to influence visitor behaviour. Visitor impact is reduced by physical separation from the natural environment, or by influencing the spatial distribution of use in order to protect sensitive areas;

- direct controls in the form of rules, regulations, permits and charges imposed and enforced in order to prohibit or restrict human behaviour which may be detrimental to the natural environment;

- indirect mechanisms which seek to reduce inappropriate behaviour through education, leading to voluntary behavioural changes. These environmental education programs are termed ‘interpretative’.

- to analyse local stakeholders’ perceptions and levels of awareness of the NoRs;

- to analyse what—if any—economic or social advantages and/or opportunities arise from the creation and development of NoRs;

- to see whether—and to what extent—actors’ participation and interactions have led to the creation of innovative tourist offers, linked to the valorisation of natural resources, focussing in particular on education and environmental interpretation;

- to understand whether involvement in the projects has created new relationships between the various actors, as mechanisms of social innovation within the communities investigated are developed.

2. Materials and Methods

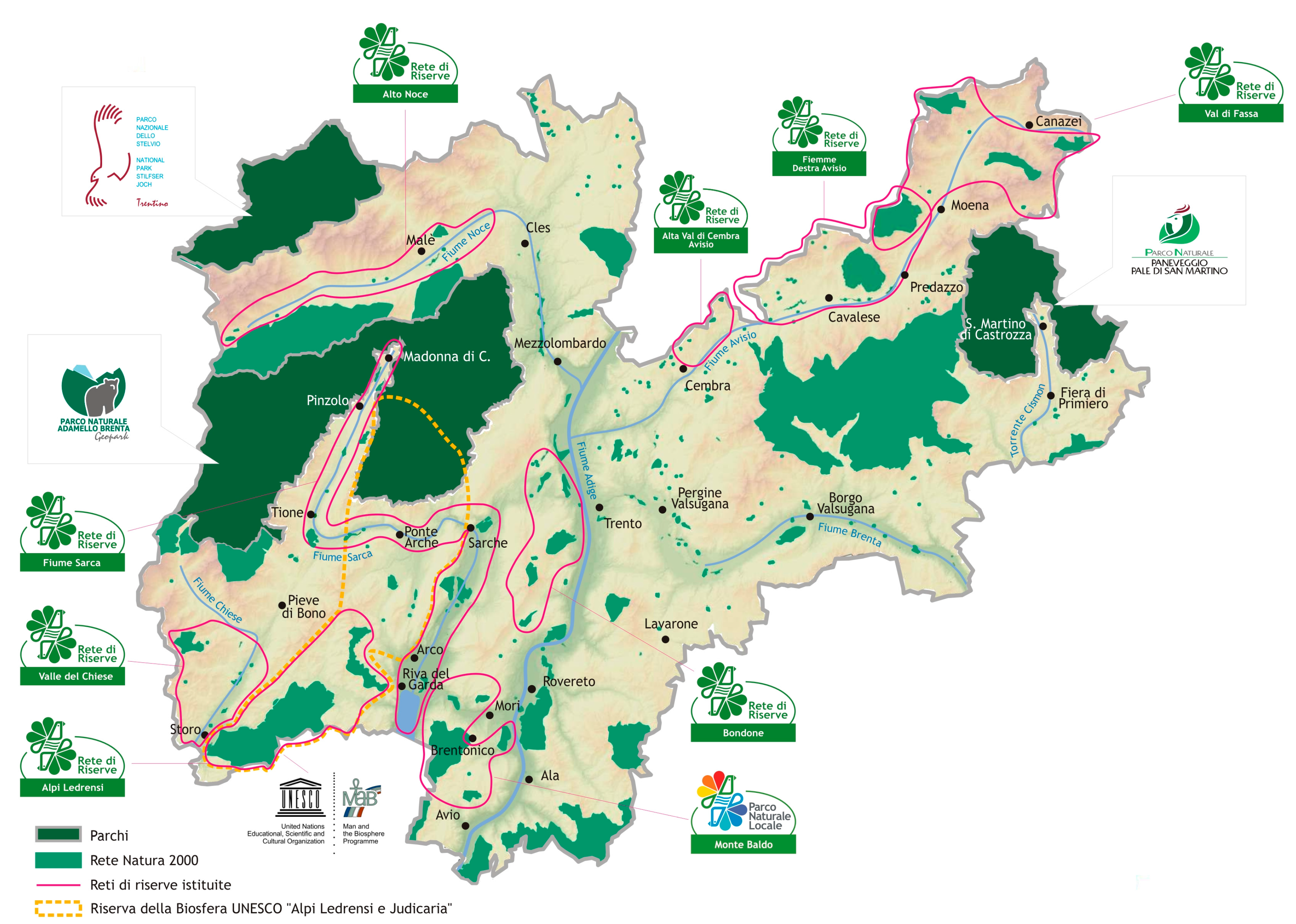

2.1. The Study Area: Networks of Reserves in Trentino

2.2. Research Design and Method

- The identification of (a) the main stakeholders who shaped, and/or are now participating in, activities and/or projects to valorise and develop the territory and (b) the most important stakeholders involved in the creation of the NoR. The importance of the stakeholders was understood both through positive approach, i.e., indicating which actors were proactive and collaborated in the NoR’s activities (key stakeholders), and through critical approach, i.e., local actors who were unenthusiastic about, or actually against the creation of the NoRs, and had, in some way, influenced and/or slowed the process (adversary stakeholders). In some cases, disinterested actors were also identified, in order to gain a broader picture of the local attitudes to, and opinions about, the NoRs.

- The identification of the main initiatives to preserve and valorise the territory.

- The identification of the activities, projects and initiatives actually carried out, and the extent to which local stakeholders collaborated in their realisation.

- the activities carried out by local stakeholders;

- stakeholders’ opinions of/satisfaction with the NoRs;

- the opportunities for and/or limitations on the territories’ socio-economic development, including tourist activities.

3. Results

3.1. The Role and Main Activities of the NoRs: Results from the Interviews with NoRs Coordinators

3.2. Stakeholders’ Perceptions and Awareness of NoRs: Main Results from the Online Survey

3.3. Linking NoRs to Sustainable Tourism: Main Results from the Interviews with DMOs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leiper, N. Tourism Systems; Massey University Press: Auckland, New Zealand, 1990; ISBN 9780473009335. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, E. Tourist Destination Management; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; ISBN 0415105919. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.; Fletcher, J.; Wanhill, S.; Gilbert, D.; Shepherd, R. Tourism: Principles and Practice; Addison Wesley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B. Some fundamental truths about tourism: Understanding tourism’s social and environmental impacts. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.; Green, H. Tourism and Environment: A Sustainable Relationship? Routledge: London, UK, 1995; ISBN 9780415085243. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, L. A strategy for tourism and sustainable development. World Leis. Recreat. 1990, 32, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Sustainable tourism: An evolving global approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 1993, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, E. Ecotourism in the Third World: Problems for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Sustainable rural tourism strategies: A tool for development and conservation. J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, V.T.C.; Hawkins, R. Sustainable Tourism: A Marketing Perspective; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Measuring tourist destination competitiveness: Conceptual considerations and empirical findings. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1999, 18, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T. Environmental management of a tourist destination: A factor of tourism competitiveness. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, M.J.; Newton, J. Tourism destination competitiveness: A quantitative approach. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; CABI Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 0851996647. [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec, J.A.; Woeber, K.; Zins, A.H. Tourism destination competitiveness: From definition to explanation? J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A Community Approach; Methuen: London, UK, 1985; ISBN 9780416397901. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.E. Community driven tourism planning. Tour. Manag. 1988, 9, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E.; Murphy, A.E. Strategic Management of Tourism Communities; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2004; ISBN 1-873150-84-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeton, S. Community Development through Tourism; Landlinks Press: Collingwood, Australia, 2006; ISBN 0643069623. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, M.C. Community benefit tourism initiatives—A conceptual oxymoron? Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, U.; Buffa, F. Local networks, stakeholder dynamics and sustainability in tourism. Opportunities and limits in the light of stakeholder theory and SNA. Sinergie 2015, 33, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Models in tourism planning: Towards integration of theory and practice. Tour. Manag. 1986, 7, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, K.M. Responsible and responsive tourism planning in the community. Tour. Manag. 1988, 9, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D.G. Community participation in tourism planning. Tour. Man. 1994, 15, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.G.; Mair, H.; George, W. Community tourism planning: A self-assessment instrument. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennel, D.A.; Dowling, R.K. Ecotourism policy and planning: Stakeholders, management and governance. In Ecotourism Policy and Planning; Fennel, D.A., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 331–344. ISBN 0851996094. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.S. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkus-Ozturk, H.; Eraydın, A. Environmental governance for sustainable tourism development: Collaborative networks and organisation building in the Antalya tourism region. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaboration and heritage management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. Managing for sustainable tourism: A review of six cultural world heritage sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppe, M. Sustainable community tourism development revisited. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Wanhill, S. (Eds.) Tourism Development: Environmental and Community Issues; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Participatory planning: A view of tourism in Indonesia. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Tosun, C. Appropriate planning for tourism in destination communities: Participation, incremental growth and collaboration. In Tourism in Destination Communities; Singh, S., Timothy, D.J., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; CABI: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 181–204. ISBN 0-85199-611-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, D.; Stewart, W.P.; Ko, D.-W. Community behaviour and sustainable rural tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, B. Public participation in community tourism planning. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G. The community approach: Does it really work? Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Sirakaya-Turk, E.; Ingram, L.J. Testing the efficacy of an integrative model for community participation. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, P. Review: Nature-based tourism. In Special Interest Tourism; Weiler, B., Hall, C.M., Eds.; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992; pp. 105–127. ISBN 9780470218433. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.; Pickering, C.; Weaver, B.B. (Eds.) Nature-Based Tourism, Environment, and Land Management; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2003; ISBN 0851997325. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Boyd, S. Nature-Based Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Development or Disaster? Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1845410001. [Google Scholar]

- Orams, M.B. Using interpretation to manage nature-based tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1996, 4, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.H. Environmental Interpretation; North American Press: Golden, CO, USA, 1992; ISBN 1-55591-902-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections and refinements. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.F.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P. Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Bagozzi, R.; Troye, S.V. Trying to prosume: Toward a theory of consumers as co-creators of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Bailey, A.; Williams, A. Aspects of service-dominant logic and its implications for tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcevschi, S. Reti ecologiche polivalenti ed alcune considerazioni sui sistemi eco-territoriali. Territorio 2011, 58, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ecosystems Ltd. Case Studies on the Article 6.3 Permit Procedure under the Habitat Directive. 2013. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/management/docs/AA_case_study_compilation.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2017).

- Grodzinska-Jurczak, M.; Cent, J. Expansion of nature conservation areas: Problems with Natura 2000 implementation in Poland? Environ. Manag. 2011, 47, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumares, D.; Fidelis, T. Local perceptions and postures towards the SPA “Ria de Aveiro”. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2009, 6, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enengel, B.; Penker, M.; Muhar, A. Landscape co-management in Austria: The stakeholder’s perspective on efforts, benefits and risks. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 34, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cent, J.; Grodzińska-Jurczak, M.; Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, A. Emerging multilevel environmental governance—A case of public participation in Poland. J. Nat. Conserv. 2014, 22, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.C.; Jordan, A.; Searle, K.R.; Butler, A.; Chapman, D.S.; Simmons, P.; Watt, A.D. Does stakeholder involvement really benefit biodiversity conservation? Biol. Conserv. 2013, 158, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, E.; Drakou, E.G.; Pediaditi, K. Participation in the management of Greek Natura 2000 sites: Evidence from a cross-level analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 113, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Jones, N.; Iosifides, T.; Florokapi, I.; Lasda, O.; Paliouras, F.; Evangelinos, K.I. Local attitudes on protected areas: Evidence from three Natura 2000 wetland sites in Greece. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, S.; Grodzinska-Jurczak, M. Should conservation of biodiversity involve private land? A Q methodological study in Poland to assess stakeholders’ attitude. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 2689–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blicharska, M.; Orlikowska, E.H.; Roberge, J.M.; Grodzinska-Jurczak, M. Contribution of social science to large scale biodiversity conservation: A review of research about the Natura 2000 network. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 199, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, S.; Paletto, A. Links between mountain communities and environmental services in the Italian Alps. Sociol. Rural. 2011, 51, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Analysis Methods and Tools | Interviews/ Questionnaires | Category of Stakeholder | Main Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: March 2017 | Face-to-face interviews Qualitative analysis | 5 interviews | NoRs Coordinators |

|

| 2: May–June 2017 | Online survey Quantitative analysis | 167 questionnaires | Key stakeholders and adversary stakeholders in the NoRs |

|

| 3: June–July 2017 | Phone interviews Qualitative analysis | 9 interviews | DMO members |

|

| Strong | Average | Weak | Not at All | NO * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provided an opportunity to promote the territory as a sustainable tourism destination. | 55.5% | 30.9% | 7.3% | 2.7% | 3.6% |

| Enabled the valorisation of valuable natural areas | 46.4% | 36.4% | 10% | 2.7% | 4.6% |

| Enabled the creation or restoration of paths. | 43.6% | 42.7% | 10.9% | 0.9% | 1.8% |

| Enabled the restoration of abandoned/degraded areas. | 30.9% | 36.4% | 24.6% | 1.8% | 6.4% |

| Strengthened their own personal connection with the territory. | 26.4% | 46.4% | 18.2% | 4.6% | 4.6% |

| Increased residents’ awareness of the importance of environmental conservation locally. | 23.6% | 50.0% | 16.4% | 2.7% | 7.3% |

| Increased awareness of sustainability within the business community. | 13.6% | 40.9% | 26.4% | 7.3% | 11.8% |

| Enabled the recovery of local traditions. | 17.3% | 35.5% | 30.9% | 6.4% | 10% |

| Increased restrictions on land use/change of use. | 6.4% | 16.4% | 27.3% | 25.5% | 24.6% |

| Hindered farming (arable/livestock) operations through restrictions imposed by protected natural area. | 2.7% | 7.3% | 23.6% | 50.9% | 15.5% |

| Projects | Stakeholder Participation | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Nature conservation (local plant and animal biodiversity, preservation and restoration of habitat). | 49.5% | 50.5% |

| Creation/restoration of paths. | 43.4% | 56.6% |

| Environmental education. | 41.4% | 58.6% |

| Organization of events/exhibitions for local residents. | 41.4% | 58.6% |

| Organization of guided tours to natural/artistic/cultural resources. | 39.4% | 60.6% |

| Promotion of local products. | 32.3% | 67.7% |

| Organization of environmental education activities in schools. | 28.3% | 71.7% |

| Valorisation of agriculture. | 26.3% | 73.7% |

| Initiatives aimed at de-seasonalizing tourism. | 23.2% | 76.8% |

| Sustainable transport. | 22.2% | 77.8% |

| Commercial development. | 5.1% | 94.9% |

| Development of handicraft sector. | 3.0% | 97.0% |

| Yes | No | Don’t Know | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Between members of the local population. | 68.2% | 14.5% | 17.3% |

| Between local business people. | 57.3% | 14.5% | 28.2% |

| Between local associations. | 85.5% | 5.5% | 9.1% |

| Between local administrators. | 84.5% | 8.2% | 7.3% |

| Between the various groups listed above. | 66.4% | 10% | 23.6% |

| Strong | Average | Weak | Non-Existent | NO * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has provided opportunities for new economic activities. | 21.8% | 33.6% | 26.4% | 4.6% | 13.6% |

| Has provided opportunities for job creation. | 14.6% | 29.1% | 40.9% | 4.6% | 10.9% |

| Has reduced local conflicts. | 4.6% | 35.5% | 30.9% | 10% | 19.1% |

| Major | Quite | Minor | Non-Existent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local management of protected natural areas. | 74.6% | 22.7% | 2.7% | 0.0% |

| Fostering public-private collaboration in the territory. | 66.4% | 30% | 3.6% | 0.0% |

| Preserving the territory by increasing the sustainability of activities carried out within it. | 63.6% | 32.7% | 3.6% | 0.0% |

| Identifying local development paths shared by the various local interest groups. | 56.4% | 39.1% | 3.6% | 0.9% |

| Stimulating innovation and identifying new economic activities. | 48.2% | 36.4% | 13.6% | 1.8% |

| Facilitating dialogue between the different categories of producer. | 47.3% | 44.6% | 8.2% | 0.0% |

| Improving the social climate through dialogue and collaboration. | 46.4% | 46.4% | 5.5% | 1.8% |

| Strong | Average | Weak | Not at All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing projects will continue, and increase their impact over time. | 22.7 | 60 | 17.3 | 0.0 |

| Current actors will remain active. | 12.7 | 69.1 | 17.3 | 0.9 |

| Actors not currently participating will probably be willing to do so in the future, leading to the growth of the network. | 13.6 | 56.4 | 28.2 | 1.8 |

| Territorial actors will be willing to invest time and money in its development. | 6.4 | 40 | 48.2 | 5.5 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martini, U.; Buffa, F.; Notaro, S. Community Participation, Natural Resource Management and the Creation of Innovative Tourism Products: Evidence from Italian Networks of Reserves in the Alps. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122314

Martini U, Buffa F, Notaro S. Community Participation, Natural Resource Management and the Creation of Innovative Tourism Products: Evidence from Italian Networks of Reserves in the Alps. Sustainability. 2017; 9(12):2314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122314

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartini, Umberto, Federica Buffa, and Sandra Notaro. 2017. "Community Participation, Natural Resource Management and the Creation of Innovative Tourism Products: Evidence from Italian Networks of Reserves in the Alps" Sustainability 9, no. 12: 2314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122314

APA StyleMartini, U., Buffa, F., & Notaro, S. (2017). Community Participation, Natural Resource Management and the Creation of Innovative Tourism Products: Evidence from Italian Networks of Reserves in the Alps. Sustainability, 9(12), 2314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122314