Abstract

A good understanding of organizational constraints is vital to facilitate organizational development as the sustainable development of organizations can be constrained by the organization itself. In this study, bibliometric methods were adopted to investigate the research status and trends of organizational constraints. The findings showed that there were 1138 articles and reviews, and 52 high-frequency keywords related to organizational constraints during the period 1980–2016. The research cores were “constraints”, “learning”, “institution”, and “behavior” in the co-occurrence network, and “constraints” played the most significant role. The 52 high-frequency keywords were classified into six clusters: “change and decision-making”, “supply chain and sustainability”, “human system and performance”, “culture and relations”, “entrepreneur and resource”, and “learning and innovation”. Furthermore, the indicators of organizational development (e.g., innovation, supply chain, decision-making, performance, sustainability, and employee behavior) were found to be significantly related to the organizational constraints. Based on these findings, future trends were proposed to maintain the sustainability of organizations. This study investigated the state of the art in terms of organizational constraints and provided valuable references for maintaining the sustainable development of organizations.

1. Introduction

The emergence of the global economy and the growing competition among organizations means that the sustainable development of organizations has become the focus of managers and researchers in organizational research. The sustainable development of organizations ensures that organizations can survive and realize their expected goals in an increasingly competitive environment for a long time into the future. Organizational development is generally measured based on organizational performance, organizational efficiency, organizational innovation, and organizational strategy, but previous studies have mainly considered factors related to employees (e.g., ability and motivation), where the research results are clear and abundant. However, some researchers consider that employees can be negatively influenced by their work situation when they are willing and able to complete one task [1]. For example, the decisions made by managers in the General Motors Corporation were constrained by their reward system from the 1930s to the 1980s, and the behavior of David Gonzalez who worked as a duty manager in Taco Bell restaurant was hindered greatly by strict institutional constraints [2]. Therefore, individual factors do not fully explain organizational performance and the organization itself also plays an important role in its sustainable development. Furthermore, few studies have considered the direct or indirect relationships between organizational constraints and sustainability. For instance, Thomas and Amadei [3] found that organizational constraints can prevent the full realization of development models; Yugendar [4] suggested that violence and social breakdown can be the most severe constraints on social sustainability; and Ikhlef [5] noted that the sustainability of dairy cattle farms in suburban areas can be constrained by environmental factors. However, previous studies lacked comprehensive and systematic considerations of how organizational constraints might maintain organizational sustainability. Thus, it is necessary to systematically investigate the state of the art in terms of organizational constraints.

The research of organizational constraints originated from Western countries in the 1980s when researchers discovered that, besides their abilities and motivations, the performances of employees can be influenced by the work situation. Furthermore, the work situation can prevent employees from fully translating their abilities and motivations into high performance [1]. Peters and O’Connor [1] first defined situational constraints as: “factors in the work environment that negatively impact performance and are beyond the employees’ control”. Subsequently, many researchers have tried to provide definitions of organizational constraints. For example, Kane [6] defined organizational constraints as: “circumstances beyond the worker’s control that may limit performance to levels below perfection”. Klein and Kim [7] defined organizational constraints as: “features of the work environment that act as obstacles to performance by preventing employees from fully translating their ability and motivation into performance”. Adkins and Naumann [8] defined organizational constraints as: “factors which place limits on the extent to which attitudes, personal attributes and motivation translate into behaviors and performance”. It should be noted that these definitions are based mostly on the perspective of the employees and organizational performance. These definitions of organizational constraints are distinct, but research into organizational constraints has been consistently similar, such as job-related information, tools and equipment, materials and supplies, budgetary support, required services and help from others, time availability, rules and procedures, being interrupted by others in the workplace, conflicting job demands, job-relevant authority, and other constraints [1,9]. Furthermore, these definitions are incomplete as many variables can be influenced by organizational constraints, but they are mostly made from the perspective of employees and organizational performance. Previous research has focused mainly on the relationships between organizational constraints and employees, performance, innovation, product, system, supply chain, and sustainability, but researchers have not been able to fully capture the latest research themes and evolutionary trends of organizational constraints as they have generally focused on a specific field. In fact, only a small number of bibliometric analyses have been performed of related topics. For instance, Villanova and Roman [10] reviewed the conceptualizations of constraints, and found that constraint scores had a weak negative relationship with performance measures according to a meta-analytic method; and Pindek and Spector [11] found that constraints as unique stressors had significant relationships with behavioral, physical, and psychological strains, as well as with well-being variables by applying a meta-analysis method. It should be noted that previous reviews focused mainly on the relationships between organizational constraints and employee characteristics and performance, but the relationships between organizational constraints and organizational development still remain unknown, and the research trends that could guide the sustainable development of organizations also need to be explored. Therefore, a descriptive review of previous research would make a great theoretical contribution because it may provide a comprehensive understanding of the state of the art in organizational constraints, and suggest further research issues that should be addressed. Furthermore, the practical implications are mainly for organizations, which can learn from the conclusions obtained in previous studies in order to reduce organizational constraints and maintain sustainable development.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the state of the art in organizational constraints, and to explore the research trends related to the maintenance of sustainable development in organizations. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we explain the methods and data collection procedure employed in this study. In Section 3, we describe the evolution of publication activities. In Section 4, we analyze the results. In Section 5, we present the research status and suggest possible future work. In Section 6, we give our conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

In science and technology studies, the co-occurrence of words is regarded as the carrier of meanings across different fields [12]. The co-word analysis method is associated with content analysis, which can be used mainly for status analysis, trend analysis, comparative analysis and citation analysis. Co-word analysis can be used to analyze the research status and trends of certain subjects or research fields by exploring the relationships among keywords or subject headings extracted by co-occurrence analysis for specific terminologies. The basis of co-word analysis is frequency analysis. First, some keywords or subject headings that are closely related to certain subjects or research fields are extracted from the literature (the frequency should usually exceed a certain critical value). A co-word matrix should then be established by developing statistics of the co-occurrence of high-frequency words in the same document. Finally, deep analysis should be performed based on the co-word matrix.

Cluster analysis can simplify the data by data modeling. In order to ensure that the similarity of data objects within the same cluster is as high as possible and that the differences in the data objects outside the same cluster are as high as possible, cluster analysis divides a set of data into different classes or clusters using a certain standard. In general, two-step cluster, K-means cluster and systematic cluster can be employed for cluster analysis, and several types of metrics can be used, such as the Euclidean distance, squared Euclidean distance, cosine, Pearson’s coefficient, and Chebychev distance.

The strategic diagram method was developed by Law et al. [13] to describe the internal relationships in certain research fields (“field” can also be replaced by “cluster”) or the interactive relationships between different research fields. The strategic diagram should be drawn based on the results of cluster analysis, and the centrality and density should be employed to measure the character of each cluster. The centrality represents the depth of the relationships between a cluster and other clusters, where a higher centrality value indicates the core status of this cluster in the entire research field. The density represents the degree of the relationships among different keywords within a cluster, where the density value reflects the ability to maintain the cluster and the development process in the research field. The strategic diagram is a two-dimensional coordinate graph, where the X-axis represents the centrality and the Y-axis represents the density, and the origin of the coordinates is the average centrality value and the average density value [14].

In this study, co-word analysis, cluster analysis, and the strategy diagram were used to analyze the research status and trends of organizational constraints, where the following procedures were performed: the first step comprised the selection of data, the second step involved the selection of keywords, co-word analysis was performed in the third step, cluster analysis was conducted in the fourth step, and the strategic diagram was produced in the last step.

2.2. Data Collection and Data Processing

The data were extracted from the Institute for Scientific Information Web of Science database which covers more than 8500 academic journals, and it has been used in many fields, such as higher education and science [15], and creativity research [16]. In this study, topics comprising “organi*ational constrain*” and “situational constrain*” were searched because the sustainability of organizations can be influenced by both organizational constraints and situational constraints. Moreover, situational constraints comprise the origin of research into organizational constraints. The asterisk widened the search range. The first definition of “situational constraints” was proposed by Peters and O’Connor in 1980 [1], so the period covered in this study was 1980–2016. The citation indexes were set as Science Citation Index Expanded and Social Science Citation Index, and the document types were then set as “article” and “review”, and the research categories were set as “management”, “economics”, and “business”. Finally, 1138 research articles and reviews were extracted from the database.

Bicomb 2.0 (Bibliographic Items Co-occurrence Matrix Builder 2.0, China Medical University, Shenyang, China) was used to process the raw data. Bicomb 2.0 was developed by Cui Lei and his team at China Medical University for processing literature records downloaded from the ISI Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and other databases. Certain fields (e.g., title, author, keywords, journal, and date of publication) can be extracted via Bicomb 2.0 and the frequency of their occurrence can be analyzed statistically. For the articles that did not contain keywords, keywords were assigned based on the title, abstract, and full text. Additionally, the co-occurrence matrix can be developed by studying high-frequency items [17]. The following processes performed before calculating the statistics for high-frequency keywords. (1) Irrelevant keywords in the organizational constraints field were deleted, such as pineapple, pillow, and other words. (2) A few keywords had similar academic meanings and the frequency of occurrence was relatively low, thereby leading to unexpected omissions in the summary of high-frequency keywords, thus the keywords with similar meanings were merged and renamed as a new keyword. For instance, “institutions”, “institutional analysis”, “institutional capital”, “institutional change”, “institutional complexity”, “institutional constraints”, “institutional context”, “institutional distance”, “institutional entrepreneurship”, “institutional environment”, “institutional gap”, “institutional influences”, “institutional isomorphism”, “institutional logics”, “institutional pressure”, “institutional regime”, “institutional theory”, “institutional transformation”, “institutional transitions”, “institutionalized trust”, and “institution-based view” were merged and renamed as “institution”; “career”, “career anchors”, “career capital”, “career development”, “career restructuration”, “career mobility”, and “career aspiration” were merged and renamed as “career”.

3. Publication Activities in the Organizational Constraints Literature

It is necessary to analyze some indicators of publication activities in order to describe the quantitative evolution and structure of organizational constraints research [18,19]. Table 1 exhibits the distribution of selected publications. Clearly, the research on organizational constraints has been growing in recent years, and this increase indicates a continuing focus on organizational constraints. It is notable that the publication output had two peaks in 2013 and 2015.

Table 1.

Annual number of selected articles related to organizational constraints.

Table 2 shows the journals that published at least ten research articles between 1980 and 2016. It can be found that “Organization Science” has published the most articles about organizational constraints (62 articles), and distantly followed by “Organization Studies” (37 articles). “Journal of Management Studies”, “Strategic Management Journal”, and “Journal of Business Ethics” rank third, fourth and fifth, respectively.

Table 2.

Journals that have published at least ten research articles.

Table 3 lists the countries and regions that have published at least ten research articles between 1980 and 2016. It can be seen that there are 20 countries and regions produced at least ten articles, and seven countries have produced more than 50 research articles. Furthermore, the USA was the largest contributor with 574 research articles about organizational constraints by the end of 2016, while England and Canada come next, ranked second and third, respectively. It should be noted that the top seven in Table 3 are all developed countries, which indicates their greater attention to organizational constraints.

Table 3.

Countries and regions that have published at least ten research articles.

Table 4 presents the institutions that have published at least ten research articles about organizational constraints. It can be found that the 25 institutions are all universities and the most productive university is University of California (43 articles), followed by University of London (34 articles) and Harvard University (26 articles). Further analysis showed that 18 of the universities are located in the USA, which indicates that researchers in the USA have a greater interest in organizational constraints.

Table 4.

Institutions that have published at least ten research articles.

It would be difficult to show every article considered in the co-word analysis, thus ten of the most frequently cited articles and their findings related to organizational constraints are listed in Table 5. The ten articles are ranked based on their citations. The article “Organizing and the process of sense making” was cited 1325 times and it was the most frequently cited article related to organizational constraints.

Table 5.

Ten of the most frequently cited articles related to organizational constraints.

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Analysis of High-Frequency Keywords

The number of high-frequency keywords can be judged and determined using the following model [30].

represents the number of high-frequency keywords, and represents the number of keywords that occurred only once.

In total, 1398 keywords occurred only once in the collected data. The number of high-frequency keywords was then calculated as 52. The high-frequency keywords and their frequencies related to organizational constraints are listed in Table 6. The range of frequency was 9–72, where “institution” ranked first (72) and “knowledge” second (67).

Table 6.

High-frequency keywords related to organizational constraints.

4.2. Co-Occurrence Network of High-Frequency Words

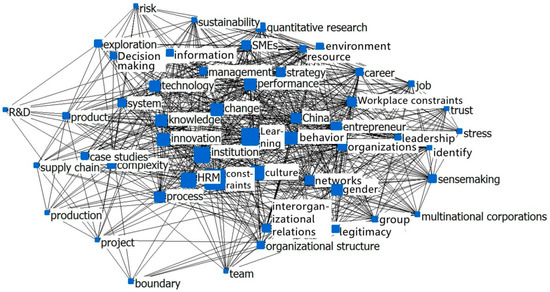

According to Yang and Xiao [31], a co-occurrence network was established by using UCINET (University of California–Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA) to visually present the relationships between the 52 high-frequency keywords. In the co-occurrence network diagram, the size of the nodes represents the intermediation between these high-frequency keywords or the ability to connect with other high-frequency keywords, and the lines represent the co-occurrence relationships between these high-frequency keywords. Therefore, when a node is large, the corresponding high-frequency keyword usually plays a key role in the co-occurrence network. The co-occurrence network related to organizational constraints was drawn on the basis of the 52 × 52 co-occurrence matrix, which was produced using the co-occurrence frequencies by arbitrarily combining the 52 high-frequency keywords. Figure 1 shows the co-occurrence network of high-frequency words related to organizational constraints. It should be noted that “constraints” had the largest node, followed by “learning”, “institution”, and “behavior”. Hence, “constraints” played the most significant role in the organizational constraints field although the frequency of “constraints” was not the highest. Additionally, “learning”, “institution”, and “behavior” were also research cores related to organizational constraints issue as they had large nodes.

Figure 1.

Co-occurrence network of high-frequency keywords.

4.3. Cluster Analysis of High-Frequency Keywords

High-frequency keywords related to organizational constraints can be categorized by cluster analysis based on a dissimilarity matrix of high-frequency keywords. The figures in the dissimilarity matrix are equal to “1” minus the figures in the correlation matrix. The co-occurrence frequencies of arbitrary combinations of the high-frequency keywords are influenced by their frequencies during the analysis of the co-occurrence matrix. Therefore, to present the co-occurrence relationships accurately, the Ochiai coefficient [32] was used to convert the co-occurrence matrix into a correlation matrix.

represents the correlation between two high-frequency keywords, represents the co-occurrence frequency between and , represents the frequency of keyword , and represents the frequency of keyword .

According to the dissimilarity matrix of high-frequency keywords, systematic cluster analysis (software: SPSS 19.0 (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA); method: Ward; metric: squared Euclidean distance) was adopted to categorize the high-frequency keywords in the organizational constraints field [33]. As shown in Table 7, the 52 high-frequency keywords could be divided into six clusters. The first cluster was designated as “change and decision-making” (C1) as it included the following keywords: “institution”, “group”, “team”, “change”, “leadership”, “decision making”, and “risk”. The second cluster was designated as “supply chain and sustainability” (C2) because it contained the following keywords: “technology”, “gender”, “system”, “management”, “sustainability”, “process”, “case studies”, “complexity”, “supply chain”, “production”, and “project”. The third, fourth, fifth, and sixth clusters were designated as “human system and performance” (C3), “culture and relations” (C4), “entrepreneur and resource” (C5), and “learning and innovation” (C6), respectively.

Table 7.

Six clusters of high-frequency keywords identified by systematic cluster analysis.

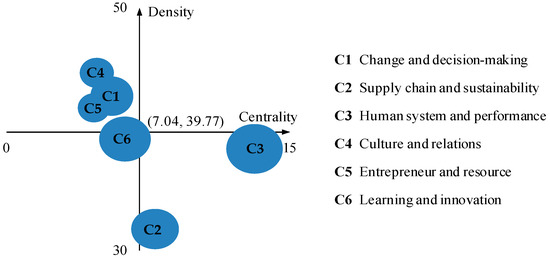

4.4. Strategic Diagram of Organizational Constraints

The following formulae [14] were applied to calculate the centralities and densities of the six clusters.

represents the centrality of cluster , represents the density of cluster , represents the co-occurrence frequency between the keyword and , represents the number of high-frequency keywords in a cluster, represents the number of all high-frequency keywords, represents the cluster , and represents the whole of the organizational constraints field. The centralities of the six clusters (in order from C1 to C6) were calculated as 5.71, 7.76, 13.11, 4.85, 4.54, and 6.25, respectively, and the densities of the six clusters were 42.83, 31.80, 38.31, 44.60, 41.80, and 39.29. The average centrality was 7.04 and the average density was 39.77. Therefore, the strategic diagram was drawn for the organizational constraints field (Figure 2) based on the centralities and densities. The size of the circle in Figure 2 is proportional to the number of articles in each cluster. Research articles about “human system and performance” were the most common, which indicates that more researchers considered “human system and performance” when focusing on organizational constraints. Furthermore, it should be noted that C1, C4 and C5 are all in the second quadrant with low centrality and high density, which indicates that they are potential research areas in the organizational constraints field, but they may disappear without further effective progress. C6 is in the third quadrant with low centrality and low density, which shows that it is a partial theme in the organizational constraints field, and it requires more attention. C2 and C3 are in the fourth quadrant with high centrality and low density, which indicates that they are potential research areas, but they are easily broken up and evolved into other clusters. Hence, the research trends in organizational constraints could be assigned to the six clusters.

Figure 2.

The strategic diagram related to organizational constraints.

5. Research Status and Trends of Organizational Constraints

5.1. Research Status of Organizational Constraints

The sustainable development of organizations is inevitably influenced by organizational constraints. Organizations generally need to learn from practical experience, but scientific research can also provide valuable references for organizations. Thus, it is necessary and important to analyze the research status of organizational constraints to maintain organizational sustainability. The research status of organizational constraints can be described as follows based on the six clusters.

C1: “Change and decision-making”: The development of an organization is largely dependent on organizational change, which aims at improve the effectiveness of organizations. Some researchers have reported that organizational change can be influenced by organizational constraints. For instance, Anderton, Conaty and Miller [34] showed that varying resistance to organizational change is mainly due to durable capital investment, and the failure to take constraints into consideration when analyzing organizational change can result in misleading results. Maier and Finger [35] found that organizational change to allow the successful introduction of organic products can be constrained by four interacting and mutually re-enforcing factors. Furthermore, the premise of organizational sustainability is reasonable for decision-making, but the decision-making process is generally hindered by organizational constraints. For example, Ordóñez and Iii [36] found that risky decision making can be constrained by time pressure. Peterson [37] showed that the decision-making processes of staffs at a Mexican national marine park could be affected by internal, external, and relational constraints. Hung and Petrick [38] noted that self-efficacy can be affected by travel constraints according to an alternative decision-making model. Friess [39] found that a strong concern for time constraints is important for making groups productive or successful in decision-making meetings. Furthermore, risk can be affected by organizational constraints, e.g., there is a positive correlation between the familial risk of breast cancer and social constraints [40], and the cash flow risk will be increased when facing financing constraints [41]. In fact, organizations can also be constrained by institutions and groups, e.g., organizational choices and investment decisions [42], and the performance of Spanish car dealerships [43] can be determined by institutional constraints. The implementation and internalization of a best management practice model in an organization can be constrained by group behavioral factors (i.e., conflicts and tensions) [44]. Teams are also closely related to organizational constraints such as decision-making behaviors of team players can be shaped by changes in practice task constraints [45], and teamwork engagement during deployment can moderate the relationship between organizational constraints and post-deployment fatigue symptoms [46]. Additionally, leadership is an important element related to organizational constraints issue as some constraints can hinder the development of leadership [47] and ratings of leadership effectiveness can mediate the relationship between organizational constraints and organizational citizenship behaviors [48].

C2: “Supply chain and sustainability”: The sustainability of organizations is found to be hindered by organizational constraints. For example, the comprehensive achievement of sustainable community development is limited by organizational constraints [3]; the sustainability of fiscal stances can be hindered by intertemporal borrowing constraints in Mexico, the Philippines and South Africa [49]; the sustainability of China can be influenced by resource constraints and environmental degradation [50]; and sustainable production is often constrained by structural factors such as industrial development, neoliberal democracy, growing population, and globalization of the consumer culture [51]. The supply chain can also be influenced by organizational constraints because it has a significant role in the organizational development process. For instance, Saldanha et al. [52] indicated that operational environments can constrain supply chain technology based on the investigations of 46 logistics and supply chain managers in India. Song and Wang [53] showed that capital constraints can reduce the profits of downstream manufacturers and even the whole supply chain, which is harmful for the sustainable development of the supply chain. Further analysis showed that technology, system, project, production and process may be constraints that influence other factors, e.g., organizational system can affect organizational performance and organizational efficiency [9,54], and technological compatibility can constrain the success of business-to-business electronic e-commerce efforts [55]. However, they can also be affected by organizational constraints, e.g., the strategic planning process can be influenced by organizational structure constraints via case analysis [56], the development of organizational information systems can be negatively impacted by organizational constraints [57], and the organizational change process may be constrained by four interacting and mutually re-enforcing factors [35]. In addition, organizational constraints are different for males and females. An investigation conducted among 231 Greek adults showed that the males had higher stress levels in terms of the interpersonal conflict scale and in organizational constraint scale [58].

C3: “Human system and performance”: People play increasingly important roles in organizational management as the driving forces of organizational development, which is becoming more people-oriented. It should be noted that components of human systems such as stress, behaviors, job, and career can also be influenced by organizational constraints. Physical strain is the first component to be influenced by organizational constraints [59,60], but organizational constraints affect other aspects related to employees, such as stress [9,48], feelings of frustration [10,61], burnout [62], work anxiety [48], job dissatisfaction [10,62], employee energy [63], career [64], counterproductive work behavior [65,66] and organizational citizenship behavior [67]. Organizational strategy and performance as important indexes of organizational sustainability are found to be negatively influenced by organizational constraints. Tannenbaum and Woods [68] demonstrated that organizational constraints can influence evaluation strategy. Steel and Mento [69] found significant effects of situational constraints on performance criteria by investigating 438 branch managers. Garriga, Krogh and Spaeth [70] found that resource constraints can decrease innovative performance via a survey of Swiss-based firms. Bacharach and Bamberger [71] found that resource inadequacy mediates the relationships between individual ability, effort, and individual performance. Brewer and Walker [72] indicated that “difficulty in removing poor managers” is harmful to organizational performance. Pindek and Spector [11] suggested that organizational constraints are contextual factors that interfere with task performance. In fact, various forms of organizational constraints in the organizational environment can have effects on organizational development, such as knowledge constraints, resource constraints, financial constraints, cultural constraints, and personnel constraints [10,27,70,72,73,74]. In addition, researchers commonly adopt quantitative research methods [74], where China [9] and small and medium enterprises [75] have been considered as samples when studying “human system and performance” issues.

C4: “Culture and relations”: The organizational culture formed to solve survival and developmental issues in organizations can be influenced by organizational constraints [47,76], but also constrain organizational management, i.e., organizational behavior management can be influenced by structural and cultural constraints [77], and the emergence of women leaders can be affected by cultural constraints [78]. Networks, including interorganizational relationships and relationships among multinational corporations, can produce unique constraints on women and racial minorities [25]. However, they are generally influenced by organizational constraints, e.g., organizational strategies and contextual constraints can influence interorganizational networks [79], transnational data flow can constrain multinational corporations in both large and small firms [80], and institutional constraints such as institutional conformist, institutional evader, institutional entrepreneur and institutional arbitrageur can hinder the implementation of emissions trading schemes in multinational corporations [81]. The trust is regarded as a relationship of dependence can also be influenced by organizational constraints, e.g., trust in organizations can be constrained by cognitive modules and emotional dispositions [82], and purchasing managers will be trusted by suppliers when they are free from constraints that limit their abilities to interpret their boundary-spanning roles [83].

C5: “Entrepreneur and resource”: Entrepreneurs play dominant roles in the development process of organizations, i.e., entrepreneurship is regarded as an organizational capacity that can allow enterprises to systematically overcome internal constraints [84], and entrepreneurial firms can succeed even when bounded by severe initial resource constraints [85,86]. Furthermore, resources are regarded as an extremely important constraint has attracted the attention of many researchers. For instance, individual ability and effort can be affected directly by inadequate resources, which can also mediate the relationships between individual ability, effort, and individual performance [72], policy change and the poor implementation of some plans in a mental health services organization can be due largely to resource constraints [87], the efforts of managers to balance the interests of stakeholders can be constrained by indivisible resources [88], innovative performance in Swiss-based firms can be constrained by the application of firm resources [70], and task performance by Machiavellian employees can be influenced by resource constraints [74]. In addition, organizational identity as a constraint can influence strategic action [89], while legitimacy is a phenomenon that can constrain change and put organizations under pressure to conform to their institutional environments [90], and people will increase skills their sense making skills when they are socialized to treat constraints as self-imposed.

C6: “Learning and innovation”. Learning and innovation are indispensable as driving forces for organizations. Organizational learning is found to be negatively related to organizational constraints, i.e., numerous constraints on organizational learning led to the difficulties in implementing a new service delivery model at a mental health services organization [87]. It should be noted that innovation is likely to develop in a free environment rather than a defined environment. Some studies have explored the relationships between organizational constraints and innovation. For instance, Caniëls and Rietzschel [91] found that perceived organizational constraints were negatively related to the practiced creativity of employees, but positively related to the creative potential of employees, and they suggested that the relationship between constraints and creativity is complex, fascinating, and understudied. Gibbert and Scranton [92] explained the negative impacts of organizational constraints on innovation. Knowledge is also an important element for organizational development as an abundance of external knowledge can increase innovative performance [70], but the development of knowledge can be influenced by constraints via a multi-perspective examination of a project [93]. In addition, the organizational structure can constrain the production of culture [76], product constraints can influence research and development team creativity [94], and the reduction of organizational slack can facilitate the migration of organizational boundary activities from the organization to the work unit level [95]. An exploratory method was also used to study the relationship between operational environments and supply chain technology [52].

5.2. Research Trends of Organizational Constraints

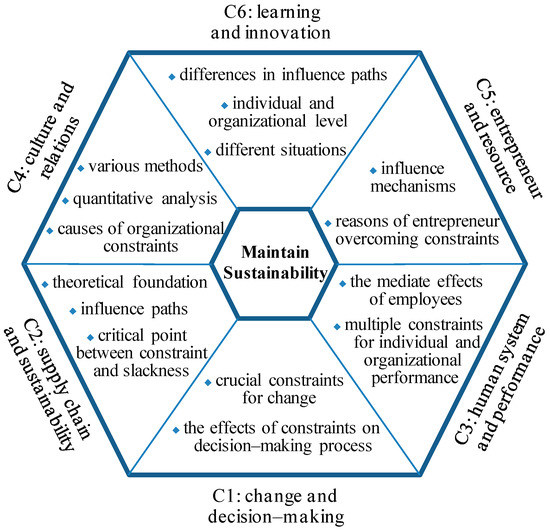

Research trends are proposed to produce an informative route map for researchers by linking the status of organizational constraints to sustainability.

First, from the perspective of “change and decision-making”, organizational change as an indispensable element for organizational development is found to be negatively influenced by some constraints, but do all constraints have negative effects on organizational change? More attention should be paid to various constraints based on previous research. Thus, it is necessary to examine the relationships between multiple constraints and organizational change by using various methods to efficiently reduce the constraints on organizational change. Furthermore, decision-making is a crucial step that will directly influence the development of organizations, but how is decision making influenced by organizational constraints? Future research should focus on more details of the decision-making process such as the critical points of organizational constraints, various risks due to organizational constraints, and intermediate effects in the relationships between organizational constraints and organizational development.

Second, from the perspective of “supply chain and sustainability”, the supply chain involving material, information, capital, and other flows cannot be ignored by organizations. The mechanisms that mediate these effects are unclear although some studies have considered the relationships between organizational constraints and the supply chain, thus more attention should be paid to the theoretical foundation and pathways that mediate various effects. In addition, the research on organizational slackness (the opposite of “organizational constraints”) should be attached great importance as both constraints and slackness can result in negative effects on organizational development. It is necessary to explore the critical point between organizational constraint and organizational slackness in order to maintain the sustainability of organizations, which is generally regarded as the optimal situation for organizations. Hence, how can organizations determine the critical point? This is a very interesting question. A gaming model should be constructed between organizational constraints and organizational development. The optimal settings can then be determined by using simulations in order to realize sustainable development in different organizational situations.

Third, from the perspective of “human system and performance”, more attention should be paid to the effects of organizational constraints on human systems (e.g., physical change, attitudes, emotions, and behaviors) as people are driving forces that affect the sustainability of organizations. Whether employees act as mediators between organizational constraints and organizational development is a very interesting question, and this is also an important issue due to the increasing competition among organizations. In addition, organizational development is closely related to individual performance and organizational performance, which can be influenced by multiple constraints, thus more methods should be adopted to deeply analyze the influences of multiple constraints on individual performance and organizational performance in different situations.

Fourth, from the perspective of “culture and relations”, culture should be given great attention as organizational sustainability can be influenced unconsciously by culture, thus the co-integration test, Granger causality test, regression analysis, and other methods should be employed to study the relationships between organizational constraints and culture. Relations can also be regarded as networks that can influence and be influenced by organizations, thus the relations among organizations and individuals should be quantitatively analyzed in depth based on interviews or questionnaire surveys. It should be notable that culture and relations are intangible, so it would be very interesting to explore their phenomena. Further research should pay more attention to the causes of organizational constraints in order to control organizational constraints in the initial stage.

Fifth, from the perspective of “entrepreneur and resource”, entrepreneur seemingly cannot be restricted by some constraints as they have a dominant role in the process of organizational development. However, can entrepreneurs be free of all constraints and what are the constraints that cannot hinder entrepreneurs? Further investigations need to be conducted to determine the reasons why entrepreneurs can overcome organizational constraints, and the relationships between entrepreneurship and the formation of constraints. In addition, resource constraints are more widespread or severe, as they have been discussed in many studies. In fact, resource constraints are generally inevitable for all organizations, and thus it is necessary to explore the influence mechanisms of resource constraints on organizations in depth in order to provide suggestions for organizations to avoid resource constraints to the greatest extent.

Sixth, from the perspective of “learning and innovation”, learning and innovation are the driving forces of organizational development, and they have been proven to be negatively related to organizational constraints, but some issues need further exploration. For instance, what are the constraints that can influence individual learning and innovation? What are the constraints that can influence organizational learning and innovation? Are the influence paths of organizational constraints on individual learning (innovation) the same as those that on organizational learning (innovation)? Can employees mediate the relationships between organizational constraints and organizational learning (innovation)? Therefore, further research should consider the influence mechanisms of multiple constraints on individual learning (innovation) and organizational learning (innovation) via various methods in different situations. Additionally, endogenous problems cannot be ignored when conducting empirical analysis.

In conclusion, extensive studies need to be conducted in the future. To visually illustrate the research trends, some core phrases that could be considered in further studies to maintain organizational sustainability are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Core phrases that could be considered in further studies for maintaining organizational sustainability.

6. Conclusions

In this study, the research status and trends of organizational constraints were studied with bibliometric methods in order to maintain the sustainability of organizations. The main conclusions are outlined as follows.

- (1)

- There were 1138 articles and reviews related to organizational constraints for the period 1980–2016. The publication activities showed that research into organizational constraints has been growing in recent years, where the most productive university is the University of California (43 articles), while “Organization Science” has published the most articles about organizational constraints (62 articles), and the USA is the largest contributor with 574 research articles by the end of 2016.

- (2)

- There were 52 high-frequency keywords of organizational constraints, such as institution, knowledge, innovation, learning, behavior, constraints, change, performance, strategy, entrepreneur, culture, human resource management, technology, gender, information, career, and so forth.

- (3)

- The research cores related to organizational constraints issues were “constraints”, “learning”, “institution”, and “behavior” in the co-occurrence network of high-frequency keywords, and “constraints” played the most significant role.

- (4)

- The high-frequency keywords were divided into six clusters comprising “change and decision-making”, “supply chain and sustainability”, “human system and performance”, “culture and relations”, “entrepreneur and resource”, and “learning and innovation”, which were all potential research areas related to organizational constraints.

- (5)

- The state of the art in organizational constraints was analyzed in depth in order to present a comprehensive picture of the research into organizational constraints, as well as to provide valuable references for organizations to reduce organizational constraints and maintain sustainable development. The indicators of organizational development (e.g., organizational change, innovation, supply chain, decision-making, learning, performance, sustainability, and employees behaviors) were found to be significantly hindered by organizational constraints based on the state of the art of organizational constraints.

- (6)

- Research trends were proposed for each cluster in order to provide an informative route map for further research, which may benefit the development of organizational constraints as a discipline.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 71473248, 71673271, 71273258, and 71603255), the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 16ZDA056), the Social Science Foundation Base Project of Jiangsu Province (No. 14JD026), 333 Project of Training High-level Talents (2016), the Research and Practice on the Graduate Educational Teaching Reform in Jiangsu Province (No. JGZZ16_078), the Program of Innovation Team Supported by China University of Mining and Technology (No. 2015ZY003), Jiangsu Philosophy and Social Sciences Excellent Innovation Cultivation Team (2017), and the “13th Five Year” Brand Discipline Construction Funding Project of China University of Mining and Technology (2017).

Author Contributions

Hong Chen and Ruyin Long conceived and designed the study; Daoyan Guo collected the data; Daoyan Guo and Hui Lu analyzed the data; Qianyi Long contributed analysis tools; and Daoyan Guo wrote and revised the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Peters, L.H.; O’Connor, E.J. Situational constraints and work outcomes: The influences of a frequently overlooked construct. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1980, 5, 391–397. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A. Organizational Behavior, 14th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 156–157. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E.; Amadei, B. Accounting for human behavior, local conditions and organizational constraints in humanitarian development models. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2010, 12, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yugendar, N. Social sustainability: Constraints and achievement. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Adapt Manag. 2014, 1, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ikhlef, S.; Brabez, F.; Ziki, B.; Bir, A.; Benidir, M. Environmental constraints and sustainability of dairy cattle farms in the suburban area of the city of Blida (Mitidja, Algeria). Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 10, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, J.S. Assessment of the situational and individual components of job performance. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 193–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H.J.; Kim, J.S. A field study of the influence of situational constraints leader-member exchange, and goal commitment on performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, C.L.; Naumann, S.E. Situational constraints on the achievement-performance relationship: A service sector study. J. Organ. Behav. 2001, 22, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Nauta, M.M.; Li, C.; Fan, J. Comparisons of organizational constraints and their relations to strains in China and the United States. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanova, P.; Roman, M.A. A meta-analytic review of situational constraints and work-related outcomes: Alternative approaches to conceptualization. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1993, 3, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindek, S.; Spector, P.E. Explaining the surprisingly weak relationship between organizational constraints and job performance. Hum. Perform. 2016, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Turner, W.A.; Bauin, S. From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Soc. Sci. Inform. 1983, 22, 191–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Bauin, S.; Courtial, J.P.; Whittaker, J. Policy and the mapping of scientific change: A co-word analysis of research into environmental acidification. Scientometrics 1988, 14, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Laville, F. Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics 1991, 22, 155–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehdarirad, T.; Villarroya, A.; Barrios, M. Research trends in gender differences in higher education and science: A co-word analysis. Scientometrics 2014, 101, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, B.; Zhao, L. Knowledge map of creativity research based on keywords network and co-word analysis, 1992–2011. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1023–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Liu, W.; Yan, L.; Zhang, H.; Hou, Y.F.; Huang, Y.N.; Zhang, H. Development of a text mining system based on the co-occurrence of bibliographic items in literature database. New Technol. Libr. Inf. Serv. 2008, 8, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides-Velasco, C.A.; Quintana-García, C.; Guzmán-Parra, V.F. Trends in family business research. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.C.; Serrano-Bedia, A.M.; Pérez-Pérez, M. Entrepreneurship and family firm research: A bibliometric analysis of an emerging field. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, G. The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, C.D. The mutual knowledge problem and its consequences for dispersed collaboration. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 346–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavetti, G.; Levinthal, D. Looking forward and looking backward: Cognitive and experiential search. Adm. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, E.M.; Brodt, S.E.; Korsgaard, M.A.; Werner, J.M. Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 513–530. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra, H. Personal networks of women and minorities in management: A conceptual framework. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 56–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, R.P.; Burnett, D.D. A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barley, S.R.; Kunda, G. Design and devotion: Surges of rational and normative ideologies of control in managerial discourse. Adm. Sci. Q. 1992, 37, 363–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Shalley, C.E. The social side of creativity: A static and dynamic social network perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkopf, L.; Almeida, P. Overcoming local search through alliances and mobility. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, J.C. Understanding Scientific Literature: A Bibliometric Approach; The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.X.; Xiao, G.H. Subject analysis of technology transfer in China based on co-word analysis. J. Intell. 2015, 34, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai, A. Zoogeographical studies on the soleoid fishes found in Japan and its neighbouring regions-II. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 1957, 22, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrauri, O.M.; Neira, D.P.; Montiel, M.S. Indicators for the analysis of peasant women’s equity and empowerment situations in a sustainability framework: A case study of cacao production in Ecuador. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderton, D.L.; Conaty, J.; Miller, G.A. Structural constraints on organizational change: A longitudinal analysis. J. Bus. Res. 1983, 11, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.; Finger, M. Constraints to organizational change processes regarding the introduction of organic products: Case findings from the Swiss food industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, L.; Iii, L.B. Decisions under time pressure: How time constraint affects risky decision making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1997, 71, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N. Choices, options, and constraints: Decision making and decision spaces in natural resource management. Hum. Organ. 2010, 69, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Petrick, J.F. Testing the effects of congruity, travel constraints, and self-efficacy on travel intentions: An alternative decision–making model. Tourism Manag. 2012, 33, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, E. Politeness, time constraints, and collaboration in decision-making meetings: A case study. Tech. Commun. Q. 2011, 20, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnur, J.B.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Montgomery, G.H.; Nevid, J.S.; Bovbjerg, D.H. Social constraints and distress among women at familial risk for breast cancer. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 28, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirth, S.; Viswanatha, M. Financing constraints, cash-flow risk, and corporate investment. J. Corp. Financ. 2011, 17, 1496–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvrande-Billon, A.; Ménard, C. Institutional constraints and organizational changes: The case of the British rail reform. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2005, 56, 675–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruñada, B.; Vázquez, L.; Zanarone, G. Institutional constraints on organizations: The case of Spanish car dealerships. Managerial. Decis. Econ. 2009, 30, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanda, M.A. Using activity analysis to identify individual and group behavioral constraints to organizational change management. J. Manag. Sustain. 2011, 1, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, V.; Araújo, D.; Duarte, R.; Travassos, B.; Passos, P.; Davids, K. Changes in practice task constraints shape decision–making behaviours of team games players. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boermans, S.M.; Kamphuis, W.; Delahaij, R.; Berg, C.E.; Euwema, M. Team spirit makes the difference: The interactive effects of team work engagement and organizational constraints during a military operation on psychological outcomes afterwards. Stress Health 2014, 30, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairholm, M.R.; Fairholm, G. Leadership amid the constraints of trust. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2000, 21, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, T.W.; Mckibben, E.S.; Greene-Shortridge, T.M.; Odle-Dusseau, H.N.; Herleman, H.A. Self-engagement moderates the mediated relationship between organizational constraints and organizational citizenship behaviors via rated leadership. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1830–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyoncu, H. Fiscal policy sustainability: Test of intertemporal borrowing constraints. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2005, 12, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash, R. The long-term outlook for economic reform in China: Resource constraints, inequalities and sustainability. Asia Europe J. 2006, 4, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Working with human nature to achieve sustainability: Exploring constraints and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, J.P.; Mello, J.E.; Knemeyer, A.M.; Vijayaraghavanm, T.A.S. Coping strategies for overcoming constrained supply chain technology: An exploratory study. Transport. J. 2015, 54, 369–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, W. Suppliers’ financing model and risk prevention under capital constraints. Bus. Econ. 2011, 12, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, T.; Korte, R. Managing knowledge performance: Testing the components of a knowledge management system on organizational performance. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2014, 15, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaefer, F.; Bendoly, E. Measuring the impact of organizational constraints on the success of business-to-business e-commerce efforts: A transactional focus. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G. Inclusive strategy: Toward integrating organization structure constraints into the strategic planning process. Int. Proc Econ. Dev. Res. 2012, 43, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, S.; Masoner, M.; Nicolaou, A. An empirical examination of the influence of organizational constraints on information systems development. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2010, 2, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafyla, A.; Kaltsidou, G.; Spyridis, N.; Theriou, N. Gender differences in work stress, related to organizational conflicts and organizational constrains: An empirical research. Int. J. Econ. Sci. Appl. Res. 2013, 6, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E.; Dwyer, D.J.; Jex, S.M. Relation of job stressors to affective, health, and performance outcomes: A comparison of multiple data sources. J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.E.; O’Connell, B.J. The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control and type A to the subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1994, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Jex, S.M. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constrains scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, R.G.; Stapleton, L.M.; Downey, R.G. Core self-evaluations and job burnout: The test of alternative models. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Cheng, H.; Zhu, D.; Long, R. Dimensions of employee energy and their differences: Evidence from Chinese insurance companies. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2016, 26, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellen, T.; Janssens, M. Enacting global careers: Organizational career scripts and the global economy as co-existing career referents. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, L.M.; Spector, P.E. Job stress, incivility, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The moderating role of negative affectivity. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Spector, P.E.; Miles, D. Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 59, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, J.; Yahya, K.K. Linking organizational structure, job characteristics, and job performance constructs: A proposed framework. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, S.I.; Woods, S.B. Determining a strategy for evaluating training: Operating within organizational constraints. Hum. Resour. Plan. 1992, 15, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, R.P.; Mento, A.J. Impact of situational constraints on subjective and objective criteria of managerial job performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1986, 37, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, H.; Krogh, V.G.; Spaeth, S. How constraints and knowledge impact open innovation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacharach, S.B.; Bamberger, P. Beyond situational constraints: Job resources inadequacy and individual performance at work. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1995, 5, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.A.; Walker, R.M. Personnel constraints in public organizations: The impact of reward and punishment on organizational performance. Public. Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T. Internal and external sources of organizational change: Corporate form and the banking industry. Sociol. Q. 2007, 48, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuyumcu, D.; Dahling, J.J. Constraints for some, opportunities for others: Interactive and indirect effects of machiavellianism and organizational constraints on task performance ratings. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnitzki, D. Research and development in small and medium–sized enterprises: The role of financial constraints and public funding. Scott. J. Political Econ. 2006, 53, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. Five constraints on the production of culture: Law, technology, market, organizational structure and occupational careers. J. Pop. Cult. 1982, 16, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulzer-Azaroff, B.; Pollack, M.J.; Fleming, R.K. Organizational behavior management within structural and cultural constraints. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 1993, 12, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.M.; Leonardelli, G.J. Cultural constraints on the emergence of women leaders: How global leaders can promote women in different cultures. Organ. Dyn. 2013, 42, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boje, D.M.; Whetten, D.A. Effects of organizational strategies and contextual constraints on centrality and attributions of influence in interorganizational networks. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samiee, S. Transnational data flow constraints: A new challenge for multinational corporations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1984, 15, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkse, J.; Kolk, A. Multinational corporations and emissions trading: Strategic responses to new institutional constraints. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichman, M. Straining towards trust: Some constraints on studying trust in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, V.; Zaheer, A.; Mcevily, B. Free to be trusted: Organizational constraints on trust in boundary spanners. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvato, C.; Sciascia, S.; Alberti, F.G. The microfoundations of corporate entrepreneurship as an organizational capability. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2009, 10, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priem, R.L.; Li, S.; Carr, J.C. Insights and new directions from demand-side approaches to technology innovation, entrepreneurship, and strategic management research. J. Manag. 2011, 38, 346–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, P.A.; Boyle, M.V. Constraints to organizational learning during major change at a mental health services facility. J. Chang. Manag. 2005, 5, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, S.J.; Schultz, F.C.; Hekman, D.R. Stakeholder theory and managerial decision-making: Constraints and implications of balancing stakeholder interests. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 64, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S.M. Organizational identity as a constraint on strategic action: A comparative analysis of gay and lesbian interest groups. Stud. Am. Polit. Dev. 2007, 21, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.C.; Sharfman, M. Legitimacy, visibility, and the antecedents of corporate social performance: An investigation of the instrumental perspective. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1558–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M.C. J.; Rietzschel, E.F. Organizing creativity: Creativity and innovation under constraints. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2015, 24, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbert, M.; Scranton, P. Constraints as sources of radical innovation? Insights from jet propulsion development. Manag. Organ. Hist. 2009, 4, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, N.; Macintosh, R.; Maclean, D.; Shepherd, J.; Stokes, J. Exploring constraints on developing knowledge: On the need for conflict. Manag. Learn. 2002, 33, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D. Creativity and constraints: Exploring the role of constraints in the creative processes of research and development teams. Organ. Stud. 2014, 35, 551–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Louis, M.R. The migration of organizational functions to the work unit level: Buffering, spanning, and bringing up boundaries. Hum. Relat. 1999, 52, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).