Exploring the Organizational Culture’s Moderating Role of Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Firm Performance: Focused on Corporate Contributions in Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR and Performance

2.2. CSR and Culture

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Firm Performance

3.2.2. CSR

3.2.3. Organizational Culture

3.2.4. Controls

3.3. Analytic Strategy

3.3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3.2. Path Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Measuring Corporate Social Performance: A Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 50–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, A.A. Data in Search of a Theory: A Critical Examination of the Relationships among Social Performance, Social Disclosure, and Economic Performance of U.S. Firms. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The Corporate Social Performance-Financial Performance Link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J. The Challenge of Measuring Financial Impacts from Investments in Corporate Social Performance. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1518–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, B.; Zhang, G. Institutional Reforms and Investor Reactions to CSR Announcements: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 1089–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Salomon, R.M. Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 1101–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it Pay to be Good? A Meta-Analysis and Redirection of Research on the Relationship between Corporate Social and Financial Performance. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 1989, 53, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.; Ferris, S.P. Agency Conflict and Corporate Strategy: The Effect of Divestment on Corporate Value. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: Correlation or Misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.; Griffiths, A. Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Antecedents and benefits of corporate citizenship: An investigation of French businesses. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 51, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E.; Cameron, K. Organizational life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: Some preliminary evidence. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliath, T.J.; Bluedorn, A.C.; Gillespie, D.F. A confirmatory factor analysis of the competing values instrument. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1999, 59, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate Social Performance Revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Sanchez-Hernandez, M.I. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility for competitive success at a regional level. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H.; Amaeshi, K.; Harris, S.; Suh, C.-J. CSR and the national institutional context: The case of South Korea. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2581–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Hong, C.S. Corporate social responsibility and firm value: Focused on corporate contributions. Korean Manag. Rev. 2009, 38, 407–432. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, P.M. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, C.A.; Ou, A.Y.; Kinicki, A. Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of the competing values framework’s theoretical suppositions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detert, J.R.; Schroeder, R.G.; Mauriel, J.J. A Framework for Linking Culture and Improvement Initiatives in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 850–863. [Google Scholar]

- Smircich, L. Concepts of Culture and Organizational Analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 45, ISBN 1557980926. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Russell, S.V.; Griffiths, A. Subcultures and sustainability practices: The impact on understanding corporate sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2009, 18, 432–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E.; Rohrbaugh, J. A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Quinn, R.E. Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005; ISBN 0787983047. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, A.L.; Ouchi, W.G. Efficient cultures: Exploring the relationship between culture and organizational performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Huang, S.-C. Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Willness, C.R.; Madey, S. Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.R. Post-innovation CSR performance and firm value. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A. Perceived external prestige, affective commitment, and citizenship behaviors. Organ. Stud. 2005, 26, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denison, D.R.; Spreitzer, G.M. Organizational culture and organizational development: A competing values approach. Res. Organ. Chang. Dev. 1991, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Carl, D.; Gupta, V.; Javidan, M. Power distance. In Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; Volume 62, pp. 513–563. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, R.; Cameron, K.; Degraff, J.; Thakor, A. Competing Values Leadership: Creating Value in Organizations; Edward Elgar Publ. Ltd.: Northhampton, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training (KRIVET). KRIVET Human Capital Corporate Panel Survey: User Guide; KRIVET: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haltiwanger, J.C.; Lane, J.I.; Spletzer, J.R. Productivity differences across employers: The roles of employer size, age, and human capital. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huselid, M. The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Turnover, Productivity, and Corporate Financial Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichniowski, C. Human resource management systems and the performance of US manufacturing businesses. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 1990, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E.; Michie, J.; Conway, N.; Sheehan, M. Human resource management and corporate performance in the UK. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2003, 41, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, W.B. Essentially Contested Concepts. Proc. Aristot. Soc. 1955, 56, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, W.E. The Terms of Political Discourse; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.F.; Monsen, R.J. On the measurement of corporate social responsibility: Self-reported disclosures as a method of measuring corporate social involvement. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 22, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.B.; Sundgren, A.; Schneeweis, T. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 854–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Maher, K.J. Cognitive theory in industrial and organizational psychology. Handb. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 1991, 2, 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luque, M.S.; Washburn, N.T.; Waldman, D.A.; House, R.J. Unrequited profit: How stakeholder and economic values relate to subordinates’ perceptions of leadership and firm performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 2008, 53, 626–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, R.A. Corporate philanthropic contributions. J. Financ. 1968, 23, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.O.; Helland, E.; Smith, J.K. Corporate philanthropic practices. J. Corp. Financ. 2006, 12, 855–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Zhang, Z. Critical mass of women on BODs, multiple identities, and corporate philanthropic disaster response: Evidence from privately owned Chinese firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, B.; Morris, S.A.; Bartkus, B.R. Having, Giving, and Getting: Slack Resources, Corporate Philanthropy, and Firm Financial Performance. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J. Women on corporate boards of directors and their influence on corporate philanthropy. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.; Rogovsky, N.; Dunfee, T.W. The next wave of corporate community involvement: Corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 44, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.; Kim, J. Outside directors, ownership structure and firm profitability in Korea. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2007, 15, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpandé, R.; Farley, J.U.; Webster, F.E., Jr. Corporate culture, customer orientation, and innovativeness in Japanese firms: A quadrad analysis. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S.; Freeman, S.J.; Mishra, A.K. Best practices in white-collar downsizing: Managing contradictions. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1991, 5, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, D. Organizational culture and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2003, 18, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R. Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1982, 67, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; White, S.; Paul, M. Linking service climate and customer perceptions of service quality: Test of a causal model. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Ed. 1993, 154, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Austin, J.T. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.; Curran, P.; Bauer, D. Computational Tools for Probing Interactions in Multiple Linear Regression, Multilevel Modeling, and Latent Curve Analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; ISBN 1134800940. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, J.M. Interaction, nonlinearity, and multicollinearity: Implications for multiple regression. J. Manag. 1993, 19, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubinski, D.; Humphreys, L.G. Assessing spurious “moderator effects”: Illustrated substantively with the hypothesized (“synergistic”) relation between spatial and mathematical ability. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deal, T.E.; Kennedy, A.A. Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Organizational Life; Deal, T., Kennedy, A., Eds.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1982; Volume 2, pp. 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Nohria, N.; Gulati, R. Is slack good or bad for innovation? Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1245–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Orv. Hetil. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. The adoption of technological, administrative, and ancillary innovations: Impact of organizational factors. J. Manag. 1987, 13, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G. Slack Resources and the Performance of Privately Held Firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, T.; Cerrato, D.; Depperu, D. Organizational slack, experience, and acquisition behavior across varying economic environments. Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, T. Slack-resources hypothesis: A critical analysis under a multidimensional approach to corporate social performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A. Corporate ethical identity as a determinant of firm performance: A test of the mediating role of stakeholder satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. Firm performance: The interactions of corporate social performance with innovation and industry differentiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, K.; Palazzo, G. Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | α 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Clan culture | My company has a family-like atmosphere | 0.945 |

| My company considers solidarity and a feeling of oneness as important | ||

| My company considers working as a team as important | ||

| Adhocracy culture | My company encourages change and innovation | 0.860 |

| My company fairly compensates innovation | ||

| My company gives more incentive to creative persons than sincere ones | ||

| Market culture | My company emphasizes competition and outcome excellence | 0.870 |

| My company believes ability related to a task is the most important requirement for employees | ||

| My company evaluates employee performance on the basis of actual outcomes | ||

| Hierarchy culture | My company emphasizes formalization and structure | 0.699 |

| My company takes a one-way, top-down approach to communication | ||

| My company emphasizes formal status and roles in the organization |

| Model | AIC/BIC a | RMSEA b | CFI/TLI c | SRMR d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-factor model | 175.568 | 269.278/464.570 | 0.183(0.158-0.209) | 0.913/0.787 | 0.098 |

| Two-factor model | 106.407 | 202.117/400.509 | 0.137(0.111-0.165) | 0.953/0.880 | 0.062 |

| Three-factor model | 60.938 | 160.649/365.240 | 0.097(0.067-0.127) | 0.978/0.940 | 0.052 |

| Four-factor model | 23.721 | 129.431/343.322 | 0.028(0.000-0.074) | 0.998/0.995 | 0.040 |

| M | S.D | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13.136 | 0.715 | ||||||||

| 2 | 11.220 | 2.394 | 0.267 ** | |||||||

| 3 | 3.326 | 0.352 | 0.239 ** | 0.250 ** | ||||||

| 4 | 3.553 | 0.375 | 0.287 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.695 ** | |||||

| 5 | 3.502 | 0.276 | 0.197 * | 0.166 * | 0.436 ** | 0.541 ** | ||||

| 6 | 3.525 | 0.335 | 0.201 * | 0.237 ** | 0.730 ** | 0.630 ** | 0.652 ** | |||

| 7 | 13.099 | 0.802 | 0.850 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.216 ** | 0.188 * | 0.158 | 0.054 | ||

| 8 | 10.989 | 2.452 | 0.220 ** | 0.779 ** | 0.227 ** | 0.289 ** | 0.187 * | 0.253 ** | 0.150 |

| Variable | Log of Sales Per Employee Ratio |

|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.467 *** (0.622) |

| 0.823 *** (0.037) | |

| 0.780 *** (0.033) | |

| 0.124 ** (0.048) | |

| Clan culture | 0.196 ** (0.063) |

| Adhocracy culture | 0.244 *** (0.065) |

| Market culture | 0.245 *** (0.068) |

| Hierarchy culture | 0.109 * (0.053) |

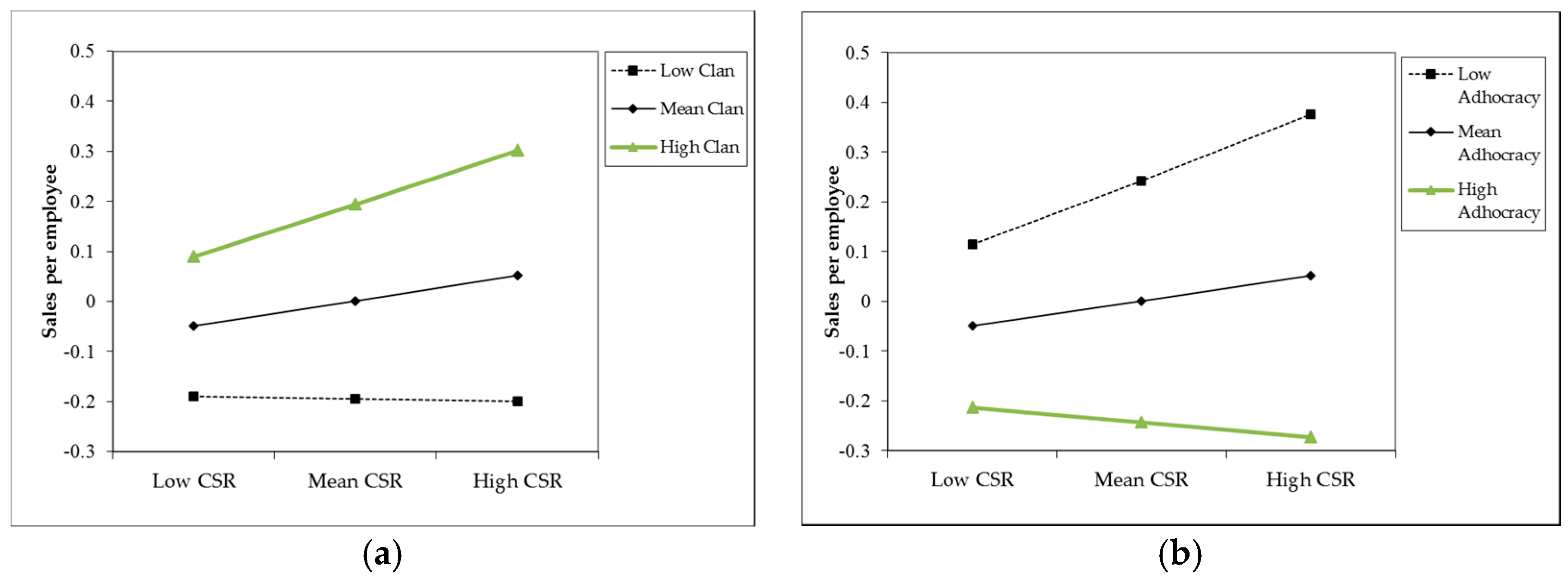

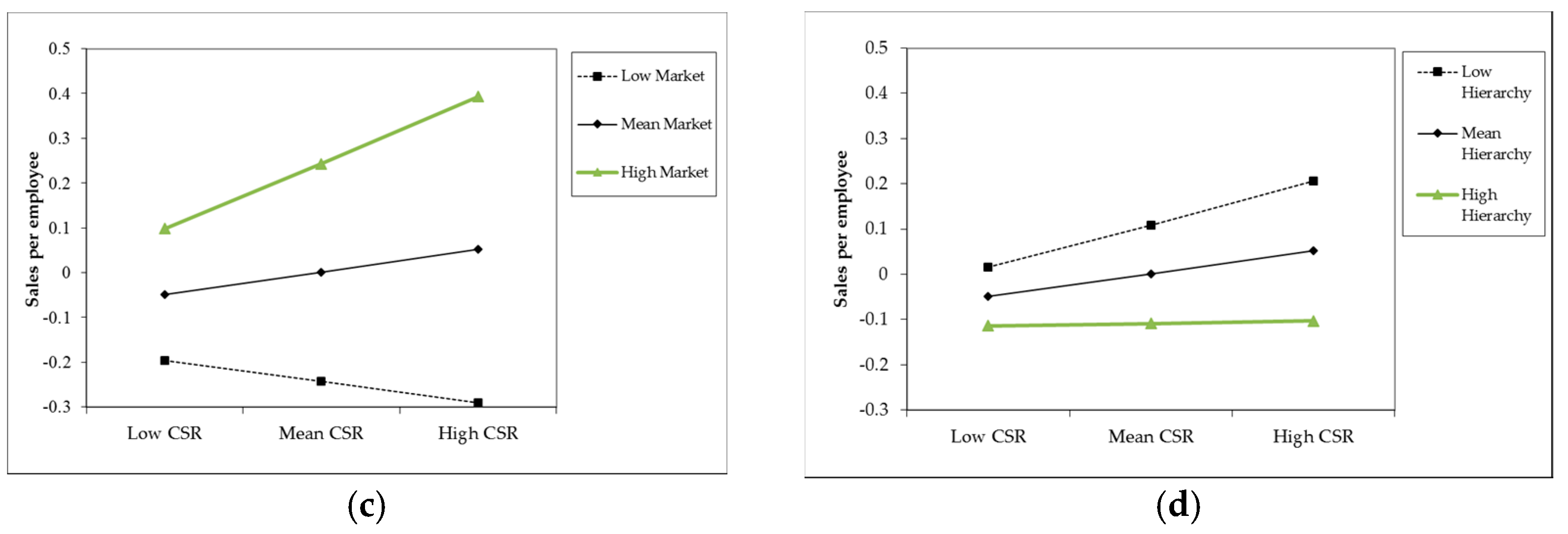

| CSR Clan | 0.141 * (0.059) |

| CSR Adhocracy | 0.202 ** (0.066) |

| CSR Market | 0.245 ** (0.072) |

| CSR Hierarchy | 0.114 * (0.051) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, M.; Kim, H. Exploring the Organizational Culture’s Moderating Role of Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Firm Performance: Focused on Corporate Contributions in Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101883

Lee M, Kim H. Exploring the Organizational Culture’s Moderating Role of Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Firm Performance: Focused on Corporate Contributions in Korea. Sustainability. 2017; 9(10):1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101883

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Myeongju, and Hyunok Kim. 2017. "Exploring the Organizational Culture’s Moderating Role of Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Firm Performance: Focused on Corporate Contributions in Korea" Sustainability 9, no. 10: 1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101883

APA StyleLee, M., & Kim, H. (2017). Exploring the Organizational Culture’s Moderating Role of Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Firm Performance: Focused on Corporate Contributions in Korea. Sustainability, 9(10), 1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101883