Abstract

The goal of this paper is twofold: to comparatively analyze the social performance of global and local berry supply chains and to explore the ways in which the social dimension is embedded in the overall performance of food supply chains. To achieve this goal, the social performance of five global and local food supply chains in two countries are analyzed: wild blueberry supply chains in Latvia and cultivated raspberry supply chains in Serbia. The study addresses two research questions: (1) What is the social performance of the local and global supply chains? (2) How can references to context help improve understanding of the social dimension and social performance of food supply chains? To answer these questions, two interlinked thematic sets of indicators (attributes) are used—one describing labor relations and the other describing power relations. These lists are then contextualized by examining the micro-stories of the actors involved in these supply chains. An analysis of the chosen attributes reveals that global chains perform better than local chains. However, a context-sensitive analysis from the perspective of embedded markets and communities suggests that the social performance of food chains is highly context-dependent, relational, and affected by actors’ abilities to negotiate values, norms, and the rules embedded within these chains, both global and local. The results illustrate that the empowerment of the chains’ weakest actors can lead to a redefining of the meanings that performance assessments rely on.

1. Introduction

Studies related to agro-food systems ever more frequently raise questions as to how sustainable current food supply chains are. These same studies underline the fact that a diversity of knowledge is needed to make a comprehensive performance evaluation in order to assess the sustainability of products reaching our tables [1,2]. Thus, contemporary studies are coming to regard food as a multi-dimensional (the effects of the system can be felt across many spheres (dimensions), most often environmental, economic, and social, yet also covering other fields of interest) [3,4] and multi-stakeholder (there are many groups that are directly and indirectly influenced by processes operating within the agro-food system) phenomenon [5,6,7]. In addition, the recognition of complexity has also prompted discussions on the reliability and relativity of evidence: aspects once interpreted as indisputable have turned out to be context-sensitive and to hold multiple meanings [2,8].

A common interpretation suggests that sustainability consists of three pillars—economic, social, and environmental [9]. However, the complexity of the processes to be assessed is most evident when one considers the social pillar (dimension) in order to analyze the sustainability of food systems [2]. This is probably one of the reasons why social aspects have often been overlooked in food chain performance assessment. However, a critical assessment of social performance is likely to bring significant benefits: investigations into the social aspects of food systems are permeated with relativity, and this quality can be helpful in shedding light on ways to negotiate and align the plural meanings of food chain dimensions and make the assessment context-sensitive. Moreover, introducing social aspects into a food system sustainability assessment involves incorporating those actors who can purposefully make improvements to the food system into the analysis: farmers, food companies, employers, workers, retailers, local communities, policy makers, and consumers.

The goal of this paper is to analyze the performance of the social dimension of the two countries’ global and local berry supply chains and to identify and analyze the nature of the links with context and the other pillars of food chain performance. This goal is pursued by analyzing five food supply chains and asking two research questions: (1) What is the social performance of the local and global supply chains (and does it differ from the other types of chains)? (2) How can references to context help improve understanding of the social dimension and social performance of food supply chains? The second question is addressed in the discussion section of this paper.

To answer these questions, the social performance of local and global berry supply chains in Latvia and Serbia are analyzed. The two selected countries have relatively limited experience with a market economy and pronounced similarities in their recent history. A set of supply chains from each country has been chosen—global and local raspberry chains in Serbia and global, local, and mixed wild blueberry chains in Latvia. The concept “supply chain” in this article has been used as an analytical generalization that describes specific arrangements between actors that ensure the flow of a product from the input materials used to the consumer. Although the study from which this paper is derived adopted a more comprehensive analysis (Undertaken within the EU’s 7th Framework Programme GLAMUR (“Global and Local food chain Assessment: a MUltidimensional peRformance-based approach”) project (CT FP7-KBBE-2012-6-311778)), this article focuses on just two performance attributes (a thematic set of measurable indicators) to assess the social dimension—labor relations and power relations. These attributes represent different levels of abstraction, and, while various interpretations of the first are often used to assess social performance [10,11], the latter attribute has been largely neglected in performance assessments. Micro-stories illustrating how various relations emerge between social performance attributes and indicators are used to revisit the initial analysis of the two attributes.

This article begins by setting out the theoretical background, while the next section describes the recent literature on how to operationalize sustainability and the social dimension and how to integrate such analysis into overall performance assessments. It continues with a brief description of the food systems and institutional settings in the two countries, Latvia and Serbia, and describes the five supply chains studied. This is followed by a section detailing the methodology used in the analysis, explaining the indicators and describing the data sources used for the study. After that, the two main attributes of social performance are analyzed. The concluding section summarizes the paper, illustrating that, if judged by indicator performance, global chains on the whole perform better than local chains. However, individual micro-stories can change the meaning of the results obtained. In this section, links between the two attributes and the context are illustrated.

2. The Social Dimension of Food Chains

The social dimension is one of several operational fields [3,4] that can be used to evaluate the sustainability of food systems. Probably the most commonly quoted sustainability definition is the one given by the Brundtland Commission, which states that “sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [12] (p. 41). This definition suggests the need to redefine relations between economic and environmental development. However, more recent theorization has suggested that sustainability consists of three mutually reinforcing and integrated pillars—economic development, social development, and environmental protection [13]. As a consequence, in the context of the search for a more elaborate and accurate view of the impacts of production and consumption, the social dimension has emerged as a recommended field for sustainability performance assessment [1,11]; researchers’ attention has shifted to what some have described as nature-society systems [2,4]. The level of the methodological sophistication of the measurement instruments associated with each of the sustainability pillars differs significantly. The social dimension lags behind in terms of both its methodological approaches and the empirical evidence it has generated [11,14,15].

The introduction of a social dimension suggested that sustainable development should be approached from the perspective of human needs, as well as from the perspective of environmental protection [12]. Yet there have been differences in the spectrum of aspects interpreted as human needs. In this paper, the social dimension is interpreted as covering the relations between social actors and the social environment these relations create. This interpretation underlines the fact that most social issues are strongly linked to the other sustainability pillars and can be characterized by a complex inner nature. Vanclay formulates the same thought as follows: “social change has a way of creating other changes” [16] (p. 185).

Although recognized as part of sustainability, it has been difficult for researchers without a strong grounding in the social sciences to acknowledge any impacts that lie outside the pool of hard evidence. This is especially so because many of these actors are quite new to social science and its theoretical basis. This is most likely the main reason why social performance has been under-researched and why in many cases, simplified explanations for this pillar of sustainability have been adopted. Some studies examine social aspects as related to welfare [17], human rights [3,10], labor experience [11], etc. To a great extent, this approach corresponds to the way in which “social” aspects are presented in global policy documents [12,13,18]. However, the recognition of the importance of the social dimension has also promoted a sophisticated academic debate on the scope and borders of social inquiry [2,4,19], how to operationalize cultural aspects [2,19,20], and the diversity of actors involved in defining social performance. These discussions illustrate the fact that social aspects are a perspective that binds performance to context and underline the importance of incorporating social actors in any assessment.

In the last decade, the methodology for social assessment has evolved significantly. For example, authors working with social impact assessment (SIA) have stated that, in order to define the “social,” researchers need to delve into concepts such as values, norms, beliefs, perception [16,21], and even human development [22]. From this perspective, “social” is reflexiveand covers different groups that can hold different interpretations [23]. Assefa and Frostell underline the scope of the social dimension, stating: “Efforts to deal with this dimension lead to a socially sustainable system that results in fairness in distribution and opportunity, and adequate provision of social services including health and education, gender equity, and political accountability and participation.” [22] (p. 65). According to Kates et al., the different ways in which researchers conceptualize the “social” represent three major variants of how the social pillar is perceived: “The first is simply a generic noneconomic social designation that uses terms such as ‘social,’ ’social development,’ and ’social progress.’ The second emphasizes human development as opposed to economic development: ’human development,’ ’human well-being,’ or just ’people.’ The third variant focuses on issues of justice and equity: ‘social justice,’ ’equity,’ and ’poverty alleviation’” [24] (p. 12).

The increasing theoretical sophistication of the social dimension is also raising questions regarding the appropriate methodological tools. Vanclay offers six pre-defined fields where social impacts can be felt (demographic, economic, geographic, institutional and legal, empowerment, and socio-cultural) [16], while Kirwan et al. propose a list of 24 mutually linked attributes of food chain performance assessment along five dimensions (economical, ecological, social, ethical, and health) that has been developed on the basis of comparative study of food chains in 12 countries [25]. Some other authors list themes that should be selected [26,27] or actors who should be considered when the social dimension is to be measured [26,27,28]. However, this methodological diversity might be illusionary. As Vanclay has observed, difficulties in developing operational definitions have often led researchers to concentrate on measurable impacts, categories that can be easily quantified or are politically convenient [16].

There is also a growing interest in reflexive methodology that incorporates context-relevant characteristics and measurement scales (see, for example, SAFA’s guidelines [29], or the guidelines for Social Life Cycle Analysis [26,27], or SIA [16,28], for different attempts to integrate these approaches [30]). This line of thinking suggests that the relevant criteria for performance assessment of social aspects should not be pre-defined since the relevant aspects and the optimal measurement instruments can vary, depending on time, place, and scope [23,31]. However, even when using context-sensitive and participatory approaches, there is a danger that methods such as participatory checklists can result in an over-reliance on the perspectives of lay experts [16]. The choice of a top-down or bottom-up assessment approach should be made in the light of contextual specificities [10,32].

An analysis of social aspects related to any type of issue/product means analyzing practices and institutional arrangements created around the research object through all its possible transformations. Thus, a narrow perspective on the product is insufficient when social performance is assessed; the analysis should rather be concentrated on supply chains built around the product. The use of the supply chain notion also allows a narrow field of evidence regarding the social aspects of sustainability to be supplemented with concepts developed in management studies, for example, global value chains (GVCs).

In this study, two attributes of fruit supply chains are analyzed—labor relations and power relations. These attributes are an analytical conceptualization for assessing particular aspects of social performance. The concept “attribute” is used to define a composite set of indicators or sub-categories. GVC literature suggests that the type of governance and power present in supply chains influences practices present in these chains [33,34,35]. Authors describing governance in GVCs go further, illustrating the different types of governance that can emerge, depending on the links between enterprises operating in chains [33]. However, this article analyzes the overall performance of supply chains, thus borrowing the argumentation for the significance of power in supply chains. GVC literature also suggests that labor relations are a central element where governance characteristics can be observed [34,36,37]. Both attributes chosen for analysis have different levels of abstraction, i.e., labor relations can be perceived as a part of a larger attribute—power relations. This corresponds to the idea presented by several authors that the impacts of social relations are multi-layered [14,16]. The selection of attributes at different scales allows us to ascertain separately each attribute’s performance; to observe how social performance is conditioned by the attributes’ inter-relations; to grasp the multi-layered nature of the social dimension; and to trace the links between the attributes. Vanclay, when commenting on the properties of SIA, suggests: “The good practice of SIA accepts that social, economic, and biophysical impacts are inherently and inextricably interconnected. Change in any of these domains will lead to changes in the other domains. SIA must, therefore, develop an understanding of the impact pathways that are created when change in one domain triggers impacts across other domains, as well as the iterative or flow-on consequences within each domain” [28] (p. 6).

3. A Comparison of Berry Supply Chains in Latvia and Serbia

In this paper, berry supply chains in Latvia and Serbia are analyzed. A study conducted by Kirwan et al. suggests that Latvia and Serbia are comparable as they are both countries with a strong focus on socio-economic and structural development: “national socio-economic development is a dominant frame that situates how global and local food chain performance is communicated and judged” [25] (p. 3). In both countries, national food systems are geared towards meeting the demands of global supply chains, in line with their priority of achieving rapid economic growth.

Although there are many differences between the two countries, they do, to some extent, share similar histories of agricultural organization, as both belong to the group of former socialist countries. The transition period to a market economy in Latvia started in the late 1980s [38]. Serbia began this transition about ten years later. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, both countries introduced decentralization policies, which among other things led to the fragmentation of agriculture. Today, in both countries, small farmers dominate the ownership structure [39], which is believed to represent the low competitiveness of agriculture. While the new guiding ideology of these countries was to become competitive in the global market, what actually happened in the 1990s was precisely the opposite; there was a decline in the competitiveness of the agricultural sector and a growth in the number of small family farms [40]. As a result, the government and markets expended significantly more effort and money to promote the biggest enterprises, while many other actors in the food chain elements were left to fend for themselves or, in the worst case scenario, pushed out of business altogether [40]. Accordingly, many smaller actors in the food chain have been marginalized, and disparities between various rural regions have increased.

This article analyzes the performance of wild blueberry supply chains in Latvia. Wild forest produce picking has strong historical and cultural roots, and, over recent decades, these have formed the basis for the emergence of a sophisticated blueberry industry. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the ensuing shock created by the introduction of a market economy, followed by more recent economic crises, have all reduced opportunities for the rural population and allowed for the expansion of the modern blueberry industry [41]. Wild blueberries are a highly valuable product, offering rural communities the chance to increase their income. At a time when there are few other opportunities, it is possible for both pickers and the enterprises that buy blueberries to make handsome profits. In addition, the low entry prices have attracted a large number of people looking to make some profit. At the same time, growing competition among the actors within these chains has led to the emergence of various adaptations (including the emergence of global chains). It is estimated that overall blueberry harvests (for both commercial purposes and home-consumption) were 9000 t in 2013, almost as large as the official apple harvest (9449 t in 2012) [42]. Data from other studies suggests that around 69,000 people (4.1% of the population) have at one time picked berries for commercial purposes [43]. Most of them only pick occasionally, although there is also a group of professional pickers who work throughout the season and make a significant profit from forest produce. By comparison, conventional forestry is responsible for just 1.5% of overall employment and agriculture for 7.3% [44]. In addition, there are also a large number of berry collecting points, numerous small networks of collectors, and a few huge enterprises operating with €1 million-plus annual turnovers. However, the sector is still relatively new, and, because of this, it remains largely invisible in the official statistics, has not attracted the interest of government institutions, and remains weakly regulated, which has led to the emergence of a multiplicity of informal and gray practices [41].

Cultivated raspberries in Serbia—a sector with a long tradition—are also analyzed. Serbia plays an important role in world raspberry production, providing 20% of the world’s yearly production of this soft fruit [45,46]. The majority of production is from small and medium-sized farms that lack the production volume to achieve the economies of scale required to provide satisfactory product margins [47]. The system is characterized by a long, fragmented supply chain and high post-harvest wastages, and does not foster competitiveness.

Access to global raspberry supply chains involves high entry costs; thus, these chains are led by large enterprises able to operate with bulk quantities. In response, the smaller farmers have been penetrating local markets and developing local supply chains. One particular problem that producers face is getting a fair share of the price paid by the consumer [48]. There is little mutual cooperation between food chain stakeholders. The government’s role in developing this sector lies within the context of broader agricultural support mechanisms. This support includes the provision of extension services, operating from national and local governmental offices, that aim to facilitate technology transfer, innovation, and improvements in production practices. This is seen as being of particular importance for local development as raspberry production has good potential for generating extra income and employment in rural regions [49].

The main actors in the supply chains analyzed are shown in Table 1. In each country, both local and global supply chains are examined. In Latvia, a third type of chain is also included in the analysis—mixed chains. Mixed supply chains were added due to the strong presence of informal economic arrangements and the reliance on social relations in these chains. GVC literature suggests that institutions operating in the chain can be both physical and social (for example, values and rules) [50] and that the chain’s central actor can enforce the rules accepted in supply chains [35]. Values and rules accepted in global and mixed blueberry chains differ, thus changing stakeholders’ experiences in these chains. The chains are termed “mixed” because they have characteristics of both global and local chains: there are both formal and informal ties, the chains are open to foreign trade but are limited to only a few neighboring countries, and they have introduced some technological solutions yet strongly rely on cultural heritage and social relations. In Serbia, the interpretation of “chain” reflects the commodity (the raspberry) being located in a certain area. In Latvia, due to a lack of data and the lack of official recognition of the sector, “chain” is interpreted as a network of actors operating around a central enterprise. In both countries, the supply chains have a historical tradition, which is associated with local supply chains. By contrast, global chains are characterized by modern technologies (and often frozen berries). In both countries, there are fewer intermediaries in the local supply chains. In Latvia, they operate within the geographical borders of the country. However, in many cases, chains tend to fuse, and the same actors can represent both local and global chains. In Serbia, local berries originate mostly from one municipality (Arilje), are protected by a quality control scheme, and are associated with specific varieties of berries (Vilamet, Miker, and Polana). Produce from Serbia for the global supply comes mostly from the regions of Sumadija and Western Serbia.

Table 1.

Actors operating in the analyzed supply chains.

The local raspberry supply chain in Serbia specifically refers to fresh raspberries from Arilje. These are a typical and specific product with a distinctive and protected origin. Most of the farms involved in producing these fresh raspberries are small farms with up to 0.5 hectares of fields under these perennial crops. The workforce mostly consists of family members and, when necessary during the picking season, seasonal workers. Labor, water, and other production inputs are local in their nature. The majority of fresh raspberry production is bought up by intermediaries (buying agents or traders) and then directed to companies that grade the fruit and transport it in refrigerated trucks to the distribution (retail) channels. Global raspberry chains are more complex and involve a significant number of foreign participants. Medium-sized and large farms are also involved in producing for these chains. As with the local chain, primary production is also dominated by the use of low input technology and the use of a seasonal labor force at harvest time. Primary storage and transportation companies play an especially important role in the global chain. They include intermediaries (buying agents/traders), cold storage companies, exporters, and cooperatives. Over 90% of the total production of raspberries in Serbia is exported in frozen form.

In Latvia, the global and mixed chains each include one of the two biggest wild blueberry processing enterprises in the country; according to some estimates, they each have around 15–20% of the wild blueberry market. Each enterprise has around 100 collecting points (places from where the actors that buy berries from those who pick them—pickers—operate) and covers around half of Latvia’s territory. The global chain specializes in the wild blueberry market and operates on a global scale. The mixed chain also works with other non-timber forest produce and operates on a regional scale (mainly the Baltic region). The global chain only collaborates with actors that follow legal practices. The chain is transparent and easily accessible to controlling institutions. In the mixed chain, many of the operations remain in the shadow (gray) economy—invisible to controlling (or any other) institutions. The global chain invests heavily in modernizing its production processes. As a result, global wild blueberry enterprises are technically advanced and manage to overcome seasonality by introducing new technical solutions and increasing imports. Meanwhile, the mixed chain expands its social networks and introduces social innovations to enhance its competitiveness. It tries to overcome seasonality by introducing new, non-timber forest produce, which could extend the operating season.

The local chain in the case of Latvia is a generalization of short supply relations and actors typically involved in picking, exchanging, selling, and consuming forest berries, as well as picking for self-consumption. This generalization is introduced in the paper because the boundaries of this chain often tend to be blurred. It does not have a central actor that would introduce rules on how the chain should operate; these rules are negotiated in interactions between the stakeholders involved. Actors in this chain receive only a minimal income, and their activities are mainly culturally driven. Such chains are uninstitutionalized and lack officially recognized enterprises and regulations (they are only indirectly regulated), and the relations between the actors are mainly personal. The forms of these relations can differ: in some cases, the pickers are consumers, or they may pass the harvest on to extended family. In other cases, the pickers are vendors. Often, these actors occupy several positions in local chains, which have their own logic based on cultural practices, and they are nested markets; however, they can also be strongly tied to global and mixed chains, despite the occasional risk of being either exploited or even swallowed up by intermediary market actors.

4. Methodology

This paper compares the performance of five supply chains: global and local raspberry supply chains in Serbia and global, mixed, and local wild blueberry supply chains in Latvia. Two methods of data analysis have been used to address the research questions. Firstly, indicators that describe the two chosen aspects of the social dimension have been analyzed. This approach illustrates the narrow interpretation of the term “social.” Secondly, micro-stories or short summaries of stakeholders’ experiences have been used.

An initial raspberry and blueberry supply chain performance assessment was based on a larger set of attributes than those presented in this paper. The selection of attributes drew strongly on Kirwan et al.’s [25] comparative analysis, defining an overall list of common attributes to be used when supply chain performance is assessed. The selection and description of indicators was also partly based on SAFA guidelines [29] and the sustainability guidelines developed by Schmitt et al. [51]. Following the suggestions of Kirwan et al. [25], SAFA [29], and other researchers [16,23,31,32], for the initial stages of creating a list of attributes to assess fruit supply chains, participatory methods were used: actors working in supply chains were consulted when the initial list of attributes had been created. Since the goal of this article is to analyze the performance of the social dimension and the relations between the attributes representing it, the list of attributes had to be shortened to just two for in-depth analysis: labor relations and power relations were chosen.

Labor relations are a commonly used attribute for assessing social performance [10,11,29,34,36,37]. In this article, both quantitative indicators, based on statistics (such as wage levels and employment relations), and qualitative indicators, based on interviews (such as health coverage and access to medical care, capacity development, the right to a quality of life, and freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining), were used for the analysis of labor relations. Power relations can only be understood at a higher level of abstraction. As the basis for this attribute, the aspects defined by Kirwan et al. [25] and SAFA [29] for attribute “governance” have been used. However, in order to capture relations that lie outside official governance procedures, the much broader concept of “power relations” is used in this paper. This concept allows supply chains to be linked to the contexts in which they operate. The indicators chosen to illustrate power relations are grievance procedures, conflict resolution, legitimacy, civic responsibility, and a platform for decision-making. These indicators capture the prevailing relations between employees, enterprises, and the general governance of the chain. A description of the indicators used is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Indicators used to assess the performance of two social attributes.

To interpret these results, the perspectives, discourses, and perceptions of actors involved in the supply chain gathered during in-depth interviews were used. Specifically, micro-stories, examples, and aggregated evidence, which illustrate the everyday experiences and practices of supply chain actors, were used. These stories highlight the fact that an apparently similar evaluation of indicator performance can be experienced in very different ways, putting the quantitative analysis of these indicators in a new light. This enables new links between the analyzed attributes and the dimensions to be introduced. In order to present a comprehensive picture of actors’ experiences within the chain, the micro-stories are built around the stories of specific actors, but combine these personal experiences with data from other sources.

Several methods were used to collect the data needed to measure the selected performance indicators and to obtain the micro-stories, such as semi-structured individual and group interviews, participatory observation, and in some cases follow-up interviews. Respondents were selected so that they would represent various supply chain actors. For the analysis of blueberry chains, 15 extensive interviews (longer than one hour) were conducted with four major blueberry dealers, four collectors, two people selling berries in short chains, a major secondary processor, a blueberry picker, and three civil servants representing government institutions. In addition, a number of shorter interviews with pickers, sellers, and consumers in short chains were conducted. For the analysis of raspberry chains, 11 one-hour-long interviews with actors holding key positions in both local and global supply chains were conducted. The interviewees included three actors representing governance institutions, two professional associations, one producer, one secondary processor, three companies involved in logistics, and one actor involved in raspberry certification. All interviews were conducted in 2014 and 2015. In order to obtain a deeper understanding of the supply chains studied, policy documents and statistical and secondary data were also analyzed. The results were verified by organizing discussions with the stakeholders.

The variety of data allows the research questions to be approached from various perspectives. Data gathering was organized in several waves. The initial wave was organized after a common list of attributes and a list of main stakeholders had been defined. The second wave was organized to gather the data needed for performance assessment. During this wave, the questions in Table 2 (indicators used to assess the performance of the social dimension) were used to complete Table 3 (performance of the attributes of labor relations and power relations). The third wave was organized to fill in any resulting knowledge gaps and to communicate the results back to the stakeholders.

Table 3.

The performance of the attributes of labor relations and power relations.

5. Experiences from Food Chains: Social Performance Processes, Relations, and Outcomes

Analysis of the five supply chains shows that there are clear differences between them in terms of their social performance. Moreover, there are clear differences between the global and the local supply chains. In many aspects, the global chains outperform the local ones. However, one has to be careful with absolute statements, as these features are inevitably shaped by the power relations present within the chains. This section integrates the analysis of indicator performance with that of the micro-stories. The analysis is divided into two sub-sections, each describing the results of our two selected attributes. The overall performance of the indicators is illustrated in Table 3, an assessment of the gathered statistical data and the in-depth interviews, following the structure of Table 2.

5.1. Labor Relations

The largest group of people operating in the supply chains are those involved in harvesting or picking. Berry collection is a seasonal occupation that attracts different groups of people with different needs. This can influence the meaning of their involvement and lead to people having different experiences of their involvement in the supply chain. Picking is hard and low-paid work that can carry many risks. For example, blueberry pickers spend long hours in forests, while both raspberry and blueberry pickers have to carry heavy loads and spend a long time in uncomfortable positions. Thus, the availability of health insurance for employees working in global raspberry chains is an important factor to consider. Collectors/farmers have different experiences. In Latvia, collectors serve as the link between pickers and the enterprises involved in processing berries. The work of collectors is simple, but unpredictable. It has no fixed time schedule—a collector never knows when he or she will have to work—and it involves much lifting of heavy boxes and careful attention. In interviews, blueberry collectors also report that there is a lot of stress in their work as the partners with whom they collaborate can make unexpected decisions. Finally, intermediaries provide the connection between the berry harvests and the processors, retailers, and/or consumers. Analysis illustrates that this group is mainly faced with less physically demanding tasks, but market competences and network building skills are required.

The results for the attribute of labor relations illustrate that there are both similarities and differences between the chains. In both countries, results are better for labor relations in the global supply chain (see Table 3). In Latvia and Serbia, enterprises representing the global chains more frequently offered legal contracts and were, in general, more involved in securing the rights of employees. However, one collector from Latvia—an elderly woman living alone in her house in the countryside and working as a collector in the global blueberry supply chain—illustrates the contradictory consequences of legal employment. Official employment results in more frequent government controls and more paperwork for her. She also has limited opportunities to influence the chain. She receives a fixed, yet lower salary than she would in the mixed chain. Yet overall, she considers herself fortunate; the biggest benefit of being legal is that she can call the police or her enterprise if she needs help, unlike collectors in the mixed chains. Thus, she feels safer.

In both chains in Serbia, most workers are employed legally and have access to capacity building. In Latvia, none of the pickers in either the global, mixed, or local supply chains had official contracts. In the mixed supply chains, collectors were also employed without contracts. This leaves these actors exposed to potential threats and without social security, or having to work exhaustingly long days. However, at the same time, these workers also have the possibility of earning more and are not tied to one specific employer. In addition, many of them have other fixed jobs, and blueberry picking just provides a seasonal side-income.

During interviews, respondents highlighted the sense of community lying behind the unregulated relations that often replaces official labor relations. One vignette that illustrates this concerns the life of a poor, unemployed elderly couple living in a rural town and operating in a mixed chain. Berry picking has become an important source of income for them. In order to increase their earnings, the couple move to the countryside every harvesting season to be closer to the forest and berries. This reduces their travel costs. In the past, they had spent some seasons living in a tent, but the collector they sell berries to recently found an abandoned house nearby where they can squat and two bicycles they can use during the picking season. While this may be an extreme case, illustrating the powerlessness of some people involved in the supply chain, it also highlights the sense of community and mutual support that can be found within the lower levels of supply chains. People in this community do a lot more than pick or collect; they exchange information, often help with food, support each other, and offer better prices. However, this sense of community can also be exploited. There were reports of stolen berries, cheating, and threats. These practices would be less common if the sector was more transparent. The blueberry case illustrates that the legality offered by global chains can be associated with safety. Yet the same safety can be, at least partially, provided by the community. None of the blueberry chains offer clear opportunities for the future, but some actors have learned how to use informality and the absence of transparency to their advantage. In some cases, this involves exploiting the weakest actors; in other examples, however, mutual care offers benefits and opportunities to everybody involved.

Latvia’s local blueberry supply chains are practically unregulated, and the actors involved are free to choose how they organize their activities. The example of a lonely pensioner illustrates this situation and the fluid relations within local berry chains. This picker uses berries in cooking and turns them into preserve, often giving them to friends, neighbors, and family. He sometimes sells some of the berries to collectors, more for the social contact than the money. His relatives who live far away receive jars of preserve when they visit. These practices strengthen social and familial ties and give this man a sense of worth. Local chains fit the concept of “chain”—they include all the actors involved from the growing stage to the consuming stage. However, these chains are extremely short and all the indicators measured here have a totally different meaning in the case of these chains. The “local chain” in this example also represents a part of the community economy, where picking ensures the identity and sense of worth of a picker and this activity provides an income, a living, and socialization for a considerable proportion of the local population.

The raspberry supply chains in Serbia are highly dependent on a seasonal work force. Some of the differences between the Latvian and Serbian supply chains relate to the specificities of the produce. Raspberries are cultivated and farmers need to be able to attract a seasonal workforce for the harvests. By contrast, blueberries are a forest product and nobody will make a loss if they go unpicked. The current economic situation and political arrangements in Latvia allow enterprises operating in this sector to buy produce from pickers without being obliged to employ them.

The raspberry sector is faced with the consequences of rural depopulation and ageing. To address this problem, it has to encourage the temporary migration of uneducated and unqualified low-paid seasonal workers during the prime fruit-picking season [53]. As is the case in Latvia, raspberry picking in Serbia is a typical source of income for marginalized groups, who on the whole are officially unemployed. In Serbia, the wages for most pickers hired as a seasonal workforce do not provide a sufficient source of income. In addition, the pickers cannot influence the hourly wage they receive and just take what is offered since their associations are not active enough to enforce a minimum wage. These workers face long working hours, often lack contracts, and have limited future prospects. In this regard, the bargaining power of pickers is very limited compared to the other actors. In addition, respondents claimed that their position was made more insecure by competition from large numbers of seasonal workers from neighboring countries (particularly Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Romania).

5.2. Power Relations

There are several sources of power that influence the performance of a supply chain. For example, in both countries, it was observed that local chains were automatically perceived as less desirable and that governing institutions were empowering and supporting larger enterprises and scaling up. The institutional context favors bigger enterprises and bigger actors have more chance to wield their market power. By contrast, other forms of operations, such as street selling, only continue to exist because of despair and a lack of alternative opportunities. In a situation where many factors favor and empower the biggest actors, it makes sense to monitor and regulate the ways in which these actors use their power. This said, there are also mechanisms in the supply chains that assist the weakest actors, but these only become visible when looking at individual micro-relations. In this article, the indicators used to assess power relations mainly reflect the concepts and principles of governance. However, the micro-stories illustrate broader, but perhaps less visible, power relations.

When comparing the results of the indicators, the global chains outperform the local ones in terms of power relations (see Table 3). In Serbia, the well-known companies that operate in the global market place great emphasis on educating their local partners. They educate farmers on new methods of production, implementing new technologies, the more intensive use of inputs, and increasing yields per hectare. In addition, these companies also supply farmers with production inputs, such as fertilizers and other chemicals, or even mediate to achieve favorable terms for the purchase of farm equipment. This works in their favor, as it means that they have some control over practices used within the chain. In Latvia, somewhat similar processes can be observed. The big global actors operate as mediators, communicating national regulations, monitoring transparency, and unifying relationships. In doing so, they gain some control over compliance with accepted legal practices. Furthermore, in both countries, global chains have introduced new approaches: international food-related standards for farmers (in Serbia) and officially employed collectors (in Latvia). These systems offer some protection to the weakest actors in the supply chain. In both the global and local raspberry chains, there are functional and officially used grievance procedures. Yet respondents hold the belief that in global chains more conflicts are resolved in an official way. Furthermore, interviews suggest that, despite the presence of community-based mechanisms to solve problems, some issues are interpreted as non-negotiable. The bigger intermediary, processing, or import and export companies in both countries can also restrict the opportunities available to the smaller actors and can limit the influence they have over the development of the sector. In Latvia, these practices are most evident in the mixed chains; in Serbia, they are a pronounced aspect of the global chains. For example, in the raspberry chains, respondents stated that some global enterprises had recently canceled contracts just before the harvest without giving farmers a proper explanation. Additionally, the significant bargaining power of big companies seems to give them the power to enforce standardized contracts on the small players, who usually cannot influence their content. In Serbia, these relations can be observed between the primary farmers and intermediaries, mainly the cold storage owners, who dictate the terms of trade and the purchase price, especially in the global chain. While officially the purchase price of raspberries is formed freely on the market (it is believed that the market will eventually sort out any price discrepancies), farmers and many members of the public believe that the intermediaries operate a cartel, which fixes this price. A statement from a representative of the Association of Raspberry Producers illustrates this point: “Producers in Western Serbia had great expectations for 2014 as several contracts with foreign buyers had been announced. The agreements guaranteed the price for all the raspberries we produced. Then, suddenly, right before harvest, these contracts were canceled!” Yet policy makers countered this by saying that “only an irresponsible company would sign a contract in March for the purchase of almost the entire raspberry crop without even knowing what the quality or market price would be … It was clear from the very beginning that it was impossible.” Every year, during the harvest season, the farmers try to pressure the government into increasing the purchase price of raspberries, leading to social tensions, involving the farmers, the intermediaries, and the government, usually as an arbitrator unwilling to intervene.

As yet, the global raspberry chain has failed to build close contacts with the local community over issues such as sustainable development and resource use. Decisions that have implications for communities are made without their involvement. By comparison, communities are more integrated in the blueberry chains: the cultural relevance of berry picking ties these enterprises to society. However, even in this case, all decision-making is highly centralized. This point distinguishes global from mixed and local supply chains. There is a paradox in the nature of the mixed chain: while it can be more oppressive for small and weak actors, it is also more embedded and community-dependent and thus offers local communities more options. This chain works through informal relations and remains a gray sector of the economy. However, what the chain lacks in official control, it gains in other areas, since pressure from communities creates invisible structures of self-control. In these chains, tacit knowledge of what is acceptable may lead to a reaction from communities and the exclusion of those who are breaching mutual, if sometimes tacit, agreements.

The experience of a collector working in a mixed chain illustrates the opportunities and threats that exist within them. After being a collector for more than twenty years, she has developed strong ties with the pickers who collaborate with her: she often feeds them, takes care of them, and organizes social events for them. The pickers are loyal to her and continue selling their berries to her and as a result she now runs one of the biggest collecting points in the surrounding area. She has switched collaborators several times during her berry-collecting career as most of these enterprises have lost her trust. She has tried to improve her position in the supply chain in several ways, even selling her berries directly to secondary processors. However, this experience proved very stressful, even though she did manage to increase her income. Once, she also mobilized other collectors in the region to stand together for fairer prices. This was successful and resulted in greater unity among them. She also currently collaborates with a small enterprise. Yet she is careful—there are no social guarantees and no safety net to protect her should things go wrong. Moreover, she is elderly and sees few other prospects. She would like to retire, yet she depends financially on her collecting point. Her experience serves as an example of how lower level actors can compensate for a lack of official power by using other ways to broker power.

However, there is another side to the story, highlighted by the experiences of a young collector who has only recently discovered the opportunities the wild berry sector offers. He does not have any illusions about the ruthlessness of the informal part of this sector. He has witnessed a colleague’s car being burnt out and a neighboring collecting point being demolished. Yet these examples have not frightened him. He explained, “If one wants to be a collector, one has to follow the rules. This includes not raising the purchasing price too much and not driving into the forest to buy berries.” All these rules restrict competition, and it is the pickers who are the main losers from these self-imposed rules. However, his experiences also illustrate that collectors are not strictly bound by the rules. He does not hesitate to pay more to some pickers, and he sells berries to several enterprises, despite having an “exclusive deal” with one buyer who offered him a set of weights, free of charge. In addition, he also sells berries at a street market in Lithuania. He explained that he was able to do this because he “knows when to stop and maintains good relations with the other collectors.” This shows that, if a collector is considered part of the community, he is allowed to bend the rules. Any aggression is mainly directed towards outsiders. However, after several years’ working as a collector, he also wants to leave the sector and to find a less stressful job.

The local supply chain for raspberries in Serbia is more similar to the mixed chain for blueberries in Latvia. However, unlike mixed chains, the local raspberry chain largely complies with national regulations. Yet some actors representing the local chain benefit from the weakness of controlling structures (particularly regarding market structure and food safety). Thus, in Serbia’s local chain, while legal practices are widely accepted, they can sometimes be substituted for shadier, quicker solutions. Conflicts, problems, and needs in this chain are often solved sporadically in an unofficial way. The same can be said about planning; although some plans might exist, most planning is unstructured. Furthermore, this chain is rooted in the community and local relations—local mutual agreements and an internal interpretation of justice. Dissatisfied with the farm gate price offered by traders or processors, producers might block regional roads in an attempt to resolve a problem directly with the national government and local authorities. Certainly, these practices might be a threat to some actors. However, so far, they have helped to raise the voice of those too weak to pursue their interests in other ways.

The local chain in Latvia is regulated only by internal transactions. The chain lacks any official regulating structures; yet this role has been substituted for the mutual control of the actors involved and an almost total power vacuum. People who become street vendors of forest produce are commonly from the lowest, most vulnerable social groups. Their involvement in this chain probably stems from a lack of other options—when all other options fail, a person can fall back on selling forest produce. There are almost no institutions involved in this chain. The example of a Roma family illustrates this point well. The family has been selling blueberries directly to consumers for almost a decade. During the harvest season, some of the family members are in the forest, while others are cleaning and selling the berries. For a family with limited options, this is one way to make a living. The price they ask for the berries is almost six times as high as they would receive from collectors. They do this by selling their berries near a seaside resort which attracts affluent visitors, thereby making their short supply chain profitable. They organize their own labor arrangements and, every year, have to renew their municipal permit for street trading. The way this family operates does not allow them to introduce a more sustainable operational model and could be regarded as a symptom of desperation. However, for now, they have their own income source.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper has analyzed the social performance of five food supply chains in two countries. The performance of the selected indicators leads to the conclusion that, in both countries, the global berry supply chains perform better in social terms. In the case of wild blueberries, people working in global chains are more frequently officially employed and employees have rights and instruments that allow them to communicate with other actors in the chain with more bargaining power. The same conclusions apply to the global raspberry supply chain, which offers official employment and bargaining opportunities. Raspberry chains also offer employees capacity development, while the global chains offer access to medical care. The analysis suggests that the social performance of the supply chains of cultivated produce is better than that of wild produce. However, this argument can be contested when taking into consideration the experiences gleaned from actors involved in these supply chains.

A common interpretation of sustainability suggests that social aspects should be taken into account when food chain performance is measured. However, a review of the literature on assessing social performance revealed a lack of common agreement as to how to assess food chains’ social performance. Studies that analyze social performance see it as being more complex to assess than economic performance. Some researchers interpret the social dimension as a closed system that can be measured with a predefined list of characteristics. This is contested by others, who see the social aspect as containing inherent relativity that can only be captured with a context-sensitive approach. In the assessment presented in this paper, the two approaches have been integrated. Two key attributes—labor relations and power relations—were chosen as criteria to assess the social performance of food chains. Additionally, short micro-stories were introduced to contextualize these attributes. Methodologically, this approach reveals that the same processes can be associated with a wide range of outcomes. Thus, the multifinality this paper has been illustrating underlines that simple reliance on a predefined set of attributes and indicators might be insufficient to explain the performance of the social dimension. Micro-stories uncover a range of meanings, which in various cases could be associated with social performance; thus, the measurement of this dimension should be fine-tuned to capture complexity instead of simplicity. Furthermore, it is possible to argue that a simple comparison of indicator performance will always favor one vision of an optimal future (emerging from the ideological vision of optimal societal processes), while an in-depth analysis reveals that there might be other future solutions as well and that these effects will be felt across other sustainability pillars, too. For example, the model of a liberal market and capitalist enterprise, and an assessment and comparison of labor and power relations based on it, already favors the bigger actors and one interpretative direction as to how food chains should be regulated. The expectations related to this comparison most likely include the belief that enterprises are to grow, improve efficiency, raise turnover, and create jobs with a subsequent improvement in the living conditions for workers and communities. This study shows that relations between powerful actors and other stakeholders in food chains might not be as straightforward. There are other possible models for how a chain can operate and generate social sustainability outcomes, such as jobs and a decent income, family and community wellbeing, rights and identity, local livelihood, and relationships with people. Under certain conditions, the empowerment of weaker actors in food chains might cause new forms of relations, where the capitalist scaling-up of production and the globalization of chains are replaced by communal sharing and community empowerment, as has been evidenced in some episodes and initiatives in all three types of berry chains. The challenge is to give a voice to and empower the weaker actors to enhance the sustainability performance of food chains. These findings partly relate to discussions in GVC literature [33,34]. This also means that a social sustainability assessment should be context-specific and actor-sensitive and should be able to reinterpret the results obtained depending on observations from context. Furthermore, the evidence given suggests that the different meanings revealed by the social dimension raise different concerns in the other sustainability dimensions. To develop this argument further, this article introduces some new considerations, suggesting that there could be unregulated relations where the community might play an important role in the global chain.

The micro-stories from actors involved in the supply chains identified the links between the selected attributes and the context. These stories reveal that the presence of legal relations introduces significant benefits for employees: partial predictability (in terms of overall workload and salary), social security, and the ability to call upon institutions for protection when needed. The blueberry case reveals that official legal relations often play an important role in allowing actors to be active in these food chains. The collector’s ability to call the police for protection is an example, as is the burning of a collector’s car or the demolition of a collecting point. Both global cases illustrate that there are external benefits from transparency and centralization. Governing actors can control these chains more easily, and it might be easier for them to promote economic development and control environmental aspects of supply chains.

However, the micro-stories enable us to construct a wider interpretation of the unstructured relations that might emerge in chains: the story of the collectors squatting in a house in the forest, of the collector improving her position in the supply chain by switching collaborators and organizing local collectors, the young collector using the absence of contracts to his advantage, or of the farmers organizing road blockades. These examples illustrate actors using a sense of community to empower themselves. Most of these responses would not be possible in a strictly-regulated market where contracts, in both global and local chains, are often drawn up under pressure from the most powerful supply chain actors.

These observations lead to the suggestion that legal relations do not always protect the weakest actors in a supply chain. Some actors are still disadvantaged by a concentration of power and are excluded from chain development planning. A simple assessment of indicator performance might be unable to identify the multiple meanings behind these indicators. Moreover, even with a higher number of indicators, something will always be missed. Both global chains illustrate this point well: they both have difficulties in collaborating with local communities, which are largely excluded from decision-making as a result. Yet the absence of legality does not necessarily lead to chaos and exploitation. In some cases, being outside officially regulated relations can promote self-organization and become a source of empowerment. This leads to the argument that “better performance” is not necessarily related to different forms of governance. It is about the power balance between actors. This balance can be influenced by various relational forms and not just those imposed by government. Secondly, it suggests that simple indicators are not sufficient to identify the complexity of sources of empowerment. Hence, to summarize this idea, it can be said that, without reference to context-obtained results, there is no clarification as to whether the current needs are met or whether the current social arrangements will still allow future societies to benefit from the same opportunities that are available to contemporary society.

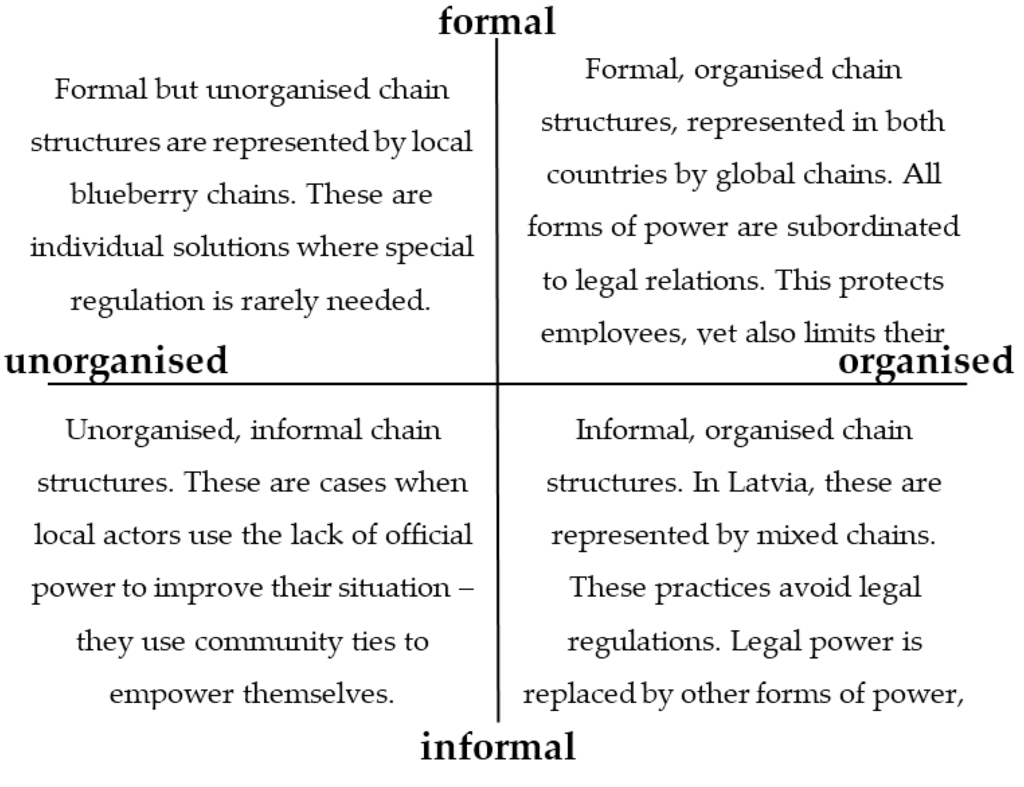

Relations between power and the aspects illustrated by the micro-stories observed in this article are presented in Figure 1. The diagram represents how different links between power, labor, and context can change the meaning of the performance of the results obtained. It illustrates the differences in opportunities that emerge from relations between market organization and the source of power. Clearly, the classification offered is one-sided and highlights only one possible way to explain the mutual links between the analyzed attributes. For example, Serbian pickers could benefit from an empowered pickers’ association if it were to emerge as a powerful actor operating in the formally-organized quadrant. Thus, legally organized power can benefit the community or legitimize community power. However, in many cases, these actors do not have the skills or are over-dependent on the actions of the strongest actors. The Serbian farmers’ reliance on the government to solve price conflicts illustrates this point. Some researchers might attribute this conclusion to the specific historical context of the countries studied. However, in many other cases across Europe, it has been observed that local small actors rely on unwritten knowledge and trust much more frequently.

Figure 1.

Organizational models for wild blueberry chains.

This study leads to the conclusion that the social dimension is relational and that social performance is embedded in specific contexts and effectuated through actors’ inter-relationships. These relations are power-permeated, and, if there are power imbalances or asymmetries in chains, the consequences will be felt firstly in social performance. In many cases, as illustrated in this paper, empowerment can result in unexpected opportunities and overall increases in well-being. Thus, the search for sources of power located outside food chains could offer actors at the lower levels of food supply chains the chance to increase the opportunities available to them.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the results from the EU’s 7th Framework Programme GLAMUR (“Global and Local food chain Assessment: a MUltidimensional peRformance-based approach”) project (CT FP7-KBBE-2012-6- 311778). We are thankful for the opportunity to receive inspiration and scientific input from our GLAMUR project colleagues. We would also like to thank Ilona Kunda for her invaluable comments on an earlier draft of this paper and Nicholas Parrott of TextualHealing.eu for his English language editing work.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data, and data analysis and interpretation. Mikelis Grivins contributed drafting the article, and all authors contributed revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guinee, J.B.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Zamagni, A.; Masoni, P.; Ekvall, T.; Rydberg, T. Life Cycle Assessment: Past, Present, Future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kates, R.W.; Clark, W.C.; Corell, R.; Hall, M.J.; Jaeger, C.C.; Lowe, I.; McCarthy, J.J.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Bolin, B.; Dickson, N.M.; et al. Sustainability Science. Science 2001, 292, 641–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čuček, L.; Klemeš, J.J.; Kravanja, Z. A Review of Footprint analysis tools for monitoring impacts on sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 34, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, B.; Urbel-Piirsalu, E.; Anderberg, S.; Olsson, L. Categorising tools for sustainability assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.; Jenkins-Smith, H. Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves, J.F. Participatory Research and Development for Sustainable Agriculture and Natural Resource Management. International Development Research Centre: Laguna, Philippines, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, P.; Stür, W. Developing Agricultural Solutions with Smallholder Farmers—How to Get Started with Participatory Approaches, No. 99. ACIAR Monograph: Canberra, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Efroymson, R.A.; Dale, V.H.; Kline, K.L.; McBride, A.C.; Bielicki, J.M.; Smith, R.L.; Parish, E.S.; Schweizer, P.E.; Shaw, D.M. Environmental Indicators of Biofuel Sustainability: What About Context? Environ. Manag. 2013, 51, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburg, M.; Govindan, K.; Sarkis, J.; Stefan, S. Quantiative models for sustainable supply chain management: Developments and directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 233, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Murty, H.; Gupta, S.; Dikshit, A. An overview of sustainability assessment methodologies. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 15, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Barling, D. Social impacts and life cycle assessment: Proposals for methodological development for SMEs in the European food and drink sector. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. World Summit Outcome; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Blanco, J.; Lehmann, A.; Muñoz, P.; Antón, A.; Traverso, M.; Rieradevall, J.; Finkbeiner, M. Application challenges for the social Life Cycle Assessment of fertilizers within life cycle sustainability assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 69, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Conceptualising social impacts. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2002, 22, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleurbaey, M. On sustainability and social welfare. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2015, 71, 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, K.M. Reporting systems for sustainability: What are they measuring? Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 100, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparatos, A.; Scolobig, A. Choosing the most appropriate sustainability assessment tool. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 80, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macombe, C.; Leskinen, P.; Feschet, P.; Antikainen, R. Social life cycle assessment of biodiesel production at three levels: A literature review and development needs. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, G.; Frostell, B. Social sustainability and social acceptance in technology assessment: A case study of energy technologies. Technol. Soc. 2007, 29, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, C.A.S.; Junior, D.J.D.B.; Gomes, J.D.O. Social Life Cycle Assessment of three companies of the furniture sector. Procedia CIRP 2015, 29, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kates, R.W.; Parris, T.M.; Leiserowitz, A.A. What is Sustainable Development? Goals, Indicators, Values, and Practice. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2005, 47, 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan, J.; Maye, D.; Bundhoo, D.; Keech, D.; Brunori, G. Scoping/Framing Food Chain Performance (WP2); GLAMUR Project (Global and Local Food Chain Assessment: A MUltidimensional Performance-Based Approach); Summary Comparative Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Benoît, C.; Mazijn, B. Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products; United Nations Environment Programme: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Benoît, C.; Norris, A.G.; Socia, V.; Andreas, C.; Asa, M.; Ulrike, B.; Siddharth, P.; Cassia, U.; Tabea, B. The guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products: Just in time! Soc. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. International Principles for Social Impact Assessment. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2003, 21, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems: Guidelines; Version 3; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogmartens, R.; Passel, V.S.; Acker, K.; Dubois, M. Bridging the gap between LCA, LCC and CBA as sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2014, 48, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuizen, L.; Bokkers, B.P.B.M.E.; de Boer, I. A method to assess social sustainability of capture fisheries: An application to a Norwegian trawler. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 53, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, L.; Scerri, A.; James, P.; Thom, J.; Padgham, L.; Hickmott, S.; Deng, H.; Cahill, F. Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Humphrey, J.; Sturgeon, T. The governance of global value chains. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2005, 12, 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, J. Global Commodity Chains: Genealogy and Review. In Frontiers of Commodity Chain Research; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J.; Schmitz, H. Governance in Global Value Chains. Inst. Dev. Stud. Bull. 2001, 32, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, S.; Gibbon, P. Quality standards, conventions and the governance of global value chains. Econ. Soc. 2006, 34, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riisgaard, L. Global value chains, labor organization and private social standards: Lessons from East Africa cut flower industries. World Dev. 2008, 37, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krūmiņš, G. Lauksaimniecības politika Latvijā: 1985–1989. Latv. Vēsturnieku Komisijas Raksti 2009, 24, 242–268. [Google Scholar]

- Šūmane, S. Lauku Inovācija: Jaunu Attīstības Prakšu Veidošana. Bioloģiskās Lauksaimniecības Piemērs. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grivins, M.; Tisenkopfs, T. A discursive analysis of oppositional interpretations of the agro-food system: A case study of Latvia. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 39, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivins, M. A comparative study of the legal and gray wild product supply chains. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. Agriculture of Latvia. Available online: http://www.csb.gov.lv/sites/default/files/nr_30_latvijas_lauksaimnieciba_2013_13_00_lv_en_0.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2016).

- Donis, J.; Straupe, I. The Assessment of Contribution of Forest Plant Non-Wood Products in Latvia’s National Economy. For. Sci. 2011, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. Employment and Unemployment. Available online: http://data.csb.gov.lv/pxweb/en/Sociala/Sociala__isterm__nodarb/?tablelist=true&rxid=a79839fe-11ba-4ecd-8cc3–4035692c5fc8 (accessed on 1 February 2016).

- Stojanović, Ž.; Radosavljević, K. Food chain, agricultural competitiveness and industrial policy: A case study of the Serbian raspberry production and export. Serbian Assoc. Econ. J. Ekon. Preduz. 2013, 3–4, 174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, I.; Miljković, M.; Okiljević, M. Potentials for export of fresh raspberries from Serbia to EU fresh markets. Industrija 2012, 40, 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Neel, S.; Bonar, H.I. Cold Chain Strategy for Serbia—Final Assessment Report; World Food Logistics Organization: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahović, B.; Puškarić, A.; Jeločnik, M. Consumer Attitude to Organic Food Consumption in Serbia. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2011, LXIII, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Simović, T.; Nesović, D.; Dabić, R. Market Analysis of the Fruit Sector in Zlatibor County; Regional Development Agency: Zlatibor, Serbia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon, T.J. From Commodity Chains to Value Chains: Interdisciplinary Theory Building in an Age of Globalization. In Frontiers of Commodity Chain Research; Bair, J., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 110–136. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, E.; Cravero, V.; Barjolle, D. WP3—Guidelines for case studies. GLAMUR Project (Global and Local Food Chain Assessment: A MUltidemensional Performance-Based Approach), Unpublished material. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grivins, M.; Tisenkopfs, T.; Stojanović, Ž.; Janković, I.; Ristić, B.; Gligorić, M. WP4 Food chain comparative report: Berry sectors in Latvia and Serbia. GLAMUR Project, Unpublished material. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zarić, V.; Vasiljević, Z.; Vlahović, B.; Andrić, J. Basic characteristics of the raspberry marketing chain and position of the small farmers in Serbia. In EAAE Seminar Book of Proceedings—Challenges for the Global Agricultural Trade Regime after Doha; Serbian Association of Agricultural Economists: Belgrade, Serbia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).