Abstract

Two rich knowledge domains have been evolving along parallel pathways in tourism studies: sustainable tourism (ST) and community-based tourism (CBT). Within both lie diverse definitions, principles, criteria, critical success factors and benefits sought or outcomes desired, advocated by different stakeholders ranging from quasi-governmental and non-profit organizations to public-private sector and academic interests. This poses significant challenges to those interested in theory building, research and practice in the sustainable development and management of tourism. The paper builds on a previous article published in Sustainability by presenting an integrated framework based on a comprehensive, in-depth review and analysis of the tourism-related literature. The study reveals not just common ground and differences that might be anticipated, but also important sustainability dimensions that are lagging or require much greater attention, such as equity, justice, ethical and governance issues. A preliminary framework of “sustainable community-based tourism” (SCBT) is forwarded that attempts to bridge the disparate literature on ST and CBT. Critical directions forward are offered to progress research and sustainability-oriented practices towards more effective development and management of tourism in the 21st century.

1. Introduction

A growing literature on sustainable tourism and community-based tourism has emerged over the past three decades in the field of tourism studies. While the discourse of sustainable tourism (ST) is oriented towards long-term sustainability, the literature on community-based tourism (CBT) looks towards local-level responsibilities and practices of tourism development and management. Numerous and diverse interpretations, definitions and practices have been forwarded within each along with a host of criticisms (see for a summary, for example, [1]). Progress towards sustainability is currently a rocky road littered with multiple definitions, indicators, stakeholders and principles [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. No serious attempt has been made to systematically examine what they mean in relation to each other and to the overall goal of sustainability in tourism development and management, even though sustainability and “community” well-being are integral to both ST and CBT and offer common grounds for reconciliation and synthesis of these two complex domains. This paper undertakes a critical analysis of the relationship between ST and CBT, the principles and concepts that guide these approaches, their origin in institutional, historical and spatio-temporal basis and similarities and differences between the two approaches. The in-depth literature review shows steady progress being made in managing environmental, social and economic impacts, but clear directions for good governance, justice and ethics tend to be lagging in both the ST and CBT discourses. It is argued here that an integrated approach is needed to advance research and management practice past the current arrays of confusions and continued isolation between these two critical areas of tourism research. Such an integrated approach could help to better address management issues related to decision making and control over the fair distribution, use and conservation of resources and to achieve the desired goals of sustainable, community-based tourism that are claimed by both ST and CBT.

The purpose of this paper is therefore to examine and offer directions forward for an integrated approach to “sustainable community-based tourism”. A comprehensive analysis of the relevant literature in tourism studies reveals that the rich knowledge domains of sustainable tourism and community-based tourism have been evolving primarily along parallel pathways in tourism. The paper traces some key developments and offers a framework to bridge these disparate discourses and to ensure that sustainability in tourism development and management is indeed grounded in community as a key principle (see the section on community-based tourism below for the meaning of “community”). The following research questions guide the study undertaken here:

- (1)

- What is the relationship between ST and CBT?

- What principles and criteria guide these concepts as discussed in the tourism literature?

- How did they arise (institutionally, historically, spatio-temporally) and why?

- What are the similarities and differences between the two approaches?

- (2)

- Is there a need to reconcile these two approaches or are they mutually exclusive?

- If integration is merited, what are the key principles or criteria that ought to guide such a reconciliation?

- Following from the above, what would an integrated framework of sustainable community-based tourism (SCBT) look like?

The paper is organized as follows. The Approach and Method Section below describes how the systematic examination of the research literature in ST and CBT was undertaken. An overview of the historic evolution of these two areas is presented in the next two sections. While some of this material is present in some form in the tourism literature, the context summarized here is important in order to understand the critique presented later in the paper. The subsequent section takes a closer look at some of the similarities and differences between ST and CBT and identifies a number of critical issues that are lagging in attention, yet are crucial in terms of sustainable development and management of tourism-related resources. A preliminary framework of “sustainable community-based tourism” (SCBT) is proposed. Critical directions forward are then offered to address a number of compelling issues that continue to hinder research and practice.

2. Approach and Method

A comprehensive literature review and analysis of ST and CBT was undertaken to get a sense of the chronology (evolution) of these terms, key organizations and stakeholders involved, key criteria and principles used in certification schemes of ST and CBT, and tourism types and approaches (e.g., pro-poor tourism, responsible tourism, ecotourism). Firstly, some steps suggested for a scoping review [9] were followed, and a few relevant scholarly journals, book chapters, book reviews and conference papers were reviewed to get a closer view of the field and to identify the search terms. The search terms included: sustainable tourism; community-based tourism; responsible tourism; (sustainable tourism) (community based tourism) framework/model/criteria/indicators/principles/definitions/certifications. Given our own management background, the initial literature search in June 2014 used the commercial literature database Business Source Complete. This search produced 375 literature records. After duplicates were removed (due to the same records being retrieved through different keyword searches), 341 records remained for further screening. Of these records, only refereed journal articles and book chapters published in English were retained (content published in a language other than English, book reviews and conference papers were removed). Again, some of the methods of search, appraisal, synthesis and analysis (SALSA) recommended as part of the scoping review process [10] were applied to the 178 journal articles and book chapters retained. Further records were gathered based on insights and recommended readings that emerged during the review process (e.g., critiques of governance and justice, recommended publications from leading international institutions in tourism, such as United Nations World Tourism Organization and United Nations Environment Program). A few conference/seminar papers were included at this stage that had been repeatedly cited (for example, [11]). All abstracts were reviewed, and articles directly pertinent to the research questions were reviewed in depth to identify major themes, concepts and issues. In total, over 200 articles and book chapters were drawn up from this preliminary search that provided valuable material for the study and helped to inform the Scopus search below.

An expanded database search was subsequently conducted in the Scopus database in spring 2016, using a similar procedure as above. However, we added a new search category here, seeking to further ascertain the relationships between ST and CBT, as well as to further explore dimensions of governance, justice and ethics. A search using the words “CBT and principles” in the title, abstract or keywords resulted in 103 records of all document. A similar search including the words “responsible tourism and principles” resulted in 50 records, and “ST and principles” revealed 417 records. Limiting results to English language publications and book chapters or articles resulted in 257 records altogether. Finally, a focused search of the words (governance OR justice OR ethics OR equity) AND (”sustainable tourism” OR “community-based tourism”), following all the above methods, but unchecking one physical science subject area, came up with 170 articles and book chapters. Interestingly, 207 articles and book chapters from the new Scopus search were duplicated in our preliminary 2014 search.

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Sustainable Development and Sustainable Tourism

A number of global institutional initiatives based in Europe began to arise in the 1970s that shaped subsequent sustainability directions. The first United Nations Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1972. It established a place on the global agenda for environmental issues, for a “point has been reached in history when we must shape our actions throughout the world with a more prudent care for their environmental consequences” [12] (p. 1). In addition, the 1972 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Convention established guidelines for the protection of global natural and cultural heritage and required states to participate in the protection and conservation of officially designated World Heritage Sites [13]. Important contributors to the subsequent discussions and initiatives were the Club of Rome’s report The Limits to Growth (for details, see [14]), and the World Conservation Strategy, 1980, was developed jointly by International Union for Conservation of Nature, United Nations Environmental Program and World Wildlife Fund (see also [15]).

The notion of sustainable development (SD) was forwarded by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (UNWCED) in the seminal Brundtland Commission’s report Our Common Future [16]. Sustainable development is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [16] (p. 8). The report raised global awareness among public and private sector institutions for the need to consider a long-term conservation horizon, as well as societal considerations, such as: (i) intra-generational and inter-generational equity in the use and conservation of environmental resources; and (ii) north-south equity, i.e., bridging the development disparities between the developed (Western) world and the lesser developed and poorer regions. This important initiative provided further momentum to growing concerns about long-term resource conservation and use.

Similar to sustainable development, sustainable tourism development, defined as a sub-set of sustainable development, witnessed some joint global institutional initiatives to direct it towards a balanced path even prior to the UNWECD (1987) initiatives. In the 1970s, UNESCO and the World Bank made an alliance for tourism development, the former supporting heritage preservation with expertise and the latter financing tourism-related infrastructure development. In 1976, these organizations jointly convened a seminar “to discuss the social and cultural impacts of tourism on developing countries and to suggest ways to take account of these concerns in decision-making” [17] (p. ix). However, the importance of addressing tourism as an important player in sustainability was not well recognized in the early initiatives mentioned above. Hall, Gossling and Scott [14] note that tourism was hardly mentioned in the UNWECD (1987) [16] report. The notion of “sustainable tourism” only later became engrained in the policy statements and planning documents of the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC).

The role of tourism did arise at the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in 1992 (also known as the Rio Summit), which sought to help operationalize sustainable development through concrete, but non-binding actions (see [18]). The Agenda 21 action plan that resulted from the Rio Summit was adopted by 182 governments present at the UNCED conference. Tourism was identified here as “one of the five main industries in need of achieving sustainable development” [5] (p. 11). The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the Earth Council (EC) subsequently jointly developed Agenda 21 for the Travel and Tourism Industry: Towards Environmentally Sustainable Development [19]. While Agenda 21 acknowledged only the potential of nature-based and low-impact tourism (ecotourism) enterprise, Agenda 21 for the Travel and Tourism Industry emphasized the need to make all travel and tourism businesses sustainable and detailed priority areas and objectives for governments and the tourism industry to comport with Agenda 21. It called for travel and trade businesses in tourism to minimize negative impacts and forge partnerships for sustainable development, including collaborating with local communities. By this time, UNWTO had also developed a clear statement on sustainable tourism:

“Sustainable tourism development meets the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunity for the future. It is envisaged as leading to management of all resources in such a way that economic, social, and aesthetic needs can be fulfilled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity, and life” support systems [20] (p. 30).

As the link between poverty and environmental degradation became clearer, the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development held in Johannesburg in 2002 focused on poverty alleviation as a key priority. Again, the role of tourism in advancing social sustainability made significant headway under discussions of responsible tourism and pro-poor tourism. “Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers” by UNEP-UNWTO [21] was a comprehensive policy document that described 12 aims of sustainable tourism development related to three “pillars” of sustainability: economic, social and environmental; also, see Figure 1 [21] (p. 20):

- (1)

- Economic sustainability, which means generating prosperity at different levels of society and addressing the cost effectiveness of all economic activity. Crucially, it is about the viability of enterprises and activities and their ability to be maintained in the long term.

- (2)

- Social sustainability, which means respecting human rights and equal opportunities for all in society. It requires an equitable distribution of benefits, with a focus on alleviating poverty. There is an emphasis on local communities, maintaining and strengthening their life support systems, recognizing and respecting different cultures and avoiding any form of exploitation.

- (3)

- Environmental sustainability, which means conserving and managing resources, especially those that are not renewable or are precious in terms of life support. It requires action to minimize pollution of air, land and water and to conserve biological diversity and natural heritage [21] (p. 9).

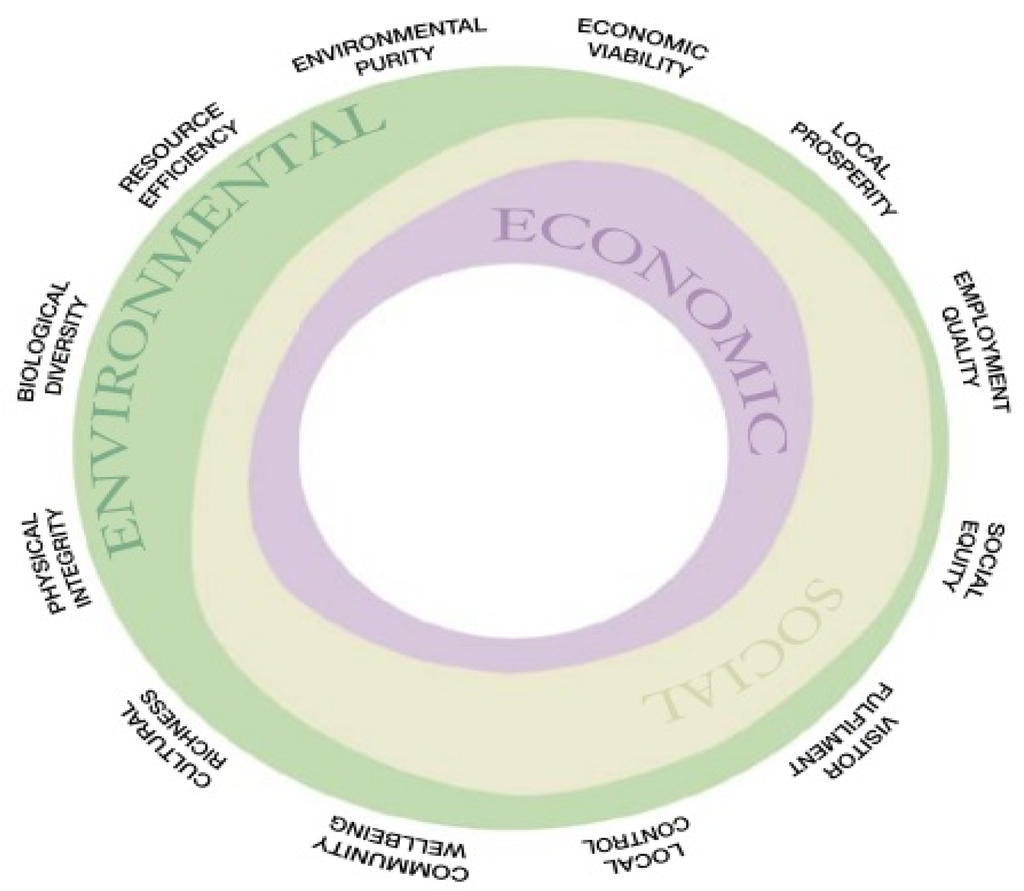

Figure 1.

Aims and pillars (dimensions) of sustainability. Source: [21] (p. 20). © “United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 92844/07/16”.

While the earlier 1994 UNWTO definition [20] of ST mentioned “host regions”, the 2005 report [21] more specifically incorporated “host communities”, equity and cultural recognition (see the second pillar in Figure 1). It described sustainable tourism as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities” [21] (p. 12). ST was envisaged here as a continuous improvement process to be applied to all forms of tourism and all types of destinations and by the key stakeholders involved in ST: tourism enterprises, local communities, environmentalists, tourists and government. Their interests have to comport with the major aims of sustainable tourism, which were further specified in the chapter Guiding Principles and Approaches of Sustainable Tourism Development from the abovementioned policy document Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers [21]. Table 1 provides a chronological view of the evolution of SD and ST development through the institutional activities summarized above.

Table 1.

Chronological evolution of sustainable development (SD) and sustainable tourism (ST) development.

A number of other initiatives are also worth noting. The UNWTO’s Global Code of Ethics for Tourism (GCET) was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1999. Its ten guiding principles were intended to facilitate tourism players in maximizing the positive impacts and minimizing the negative impacts of tourism on the natural and cultural environment in the world [26]. Articles 4 and 5 of the GCET highlight the benefits of tourism to host countries and communities and lay some obligations on its stakeholders. Yet another global system emerged in August 2010 as the result of a merger between the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) and the Sustainable Tourism Stewardship Council (STSC) in September 2009. This new GSTC umbrella organization has a diverse, global membership base, including UN agencies, leading travel companies, hotels, country tourism boards and tour operators, to foster sustainable tourism practices. Its criteria are intended to especially apply to hotels, tour operators and destinations and are organized under four pillars ([27], [28] (p. 217)):

- (1)

- Demonstrate sustainable destination management

- (2)

- Maximize economic benefits to the host community and minimize negative impacts

- (3)

- Maximize benefits to communities, visitors and culture; minimize negative impacts

- (4)

- Maximize benefits to the environment and minimize negative impacts.

The GSTC states that the destination criteria and performance indicators “were developed based on already recognized criteria and approaches, including, for example, the UNWTO destination level indicators, GSTC Criteria for Hotels and Tour Operators, and other widely accepted principles and guidelines, certification criteria and indicators” [27] (Section 2, Paragraph 4). While the GSTC’s pillars and criteria are exemplary in addressing social and cultural impacts and issues, in addition to the interrelated environmental and economic interests that drove earlier initiatives, such as the UNWCED’s Brundtland Commission report, critics point out that most of the certifications and initiatives forwarded tend to require voluntary compliance (aided by incentives) and continue to lack regulatory oversight and enforcement [29]. As Butler [4] and Wall [30] felt, sustainable tourism seemed to be more oriented towards sustaining tourism in the long-term (without adequate consideration of the trade-offs and costs involved).

3.2. Civil Society Organizations and Academic Sustainability

A number of civil society, non-profit organizations, as well as academic influences have emerged over time and much more quickly recognized the need to integrate social and environmental sustainability. The Brundtland Commission report [16], Agenda 21, the UNWTO (1994) definition [20] and the associated Agenda 21 for Travel and Tourism had focused primarily on environmental conservation in the early phases. By contrast, the fact that tourism drew on environmental and social-cultural good found in the public sector (not just under private property) raised tremendous challenges in terms of the public good and societal well-being.

Sexual and worker exploitation and mitigating the adverse impacts of sex tourism in places such as Bangkok, Thailand, were early concerns of the Ecumenical Coalition on Tourism in the 1980s [31]. Alternative approaches to tourism favoring small-scale, environmentally-friendly, locally-based tourism were advocated and seen to offer hope for locally-driven action and control over economic development, environmental and cultural conservation, as well as poverty alleviation and capacity building in the lesser developed regions in the south [32,33,34]. The notion of “responsible tourism” (RT) that arose in the 1980s fit the spirit of the alternative tourism movement of the 1970s [35]. The RT agenda was oriented towards local well-being, and according to Goodwin, “recognizes the importance of cultural integrity, ethics, equity, solidarity, and mutual respect placing quality of life at its core” [6] (p. 16). Emerging tourism forms included “soft and educational tourism (Krippendorf, 1982), cooperative tourism (Farrell, 1986), appropriate tourism (Richter, 1987), responsible tourism (Wheeler, 1991), special-interest tourism (Hall and Weiler, 1992), ecotourism (Boo, 1990; Ceballos-Lascurain, 1991) and… pro-poor tourism” as mentioned by Miller and Twining-Ward [36] (p. 31). Pro-poor tourism (PPT) arose as a specialized, small-scale, community-based approach to poverty alleviation in South Africa, spreading regionally, e.g., to The Gambia, Tanzania, Egypt [37,38,39,40] and further [41,42,43]. More recent forms such as agritourism (farm tourism), cultural tourism and volunteer tourism are evident in both the north and the south [29].

Following the global advocacy of sustainable development by the Brundtland Commission’s report, the World Wildlife Fund commissioned Tourism Concern, a U.K.-based nonprofit organization, to prepare a discussion paper on “sustainable tourism” in 1992. Tourism Concern’s report focused on both environmental and social sustainability, as the four key principles for sustainable tourism it forwarded shows: sustainable use of resources; reducing over-consumption and waste; maintaining diversity; and supporting local communities. It specifically recommended six processes: “integrating tourism into planning; involving local communities; consulting stakeholders and the public; training staff; marketing tourism responsibly; and undertaking research” [6] (pp. 14–15). The academic community followed suit. The launch of the Journal of Sustainable Tourism (JOST) in 1993 reflected rising interest in the academic community to undertake research and inform theory development and the practice of sustainable tourism. Its founding editors, Bill Bramwell and Bernard Lane, identified four sustainability principles in their first JOST editorial that similarly recognized the importance of addressing social well-being and identified four key stakeholders: the tourism industry, host communities, government and visitors [44].

Numerous research articles, critiques and reviews have followed the rise of the sustainable tourism agenda. A few noted early on the need to reconcile sustainable development and sustainable tourism development (see, for example, [45,46,47]. Farrell and Twining-Ward [48] presented sustainable tourism as a complex and dynamic system requiring careful management, including resiliency planning, risk assessment, hazard mitigation and adaptive planning. Collaborative planning for sustainable tourism and multi-stakeholder involvement are key principles for good governance and management [49,50]. Handbooks, such as the Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability (Edited by C. Michael Hall, Stefan Gossling and Daniel Scott) [23] and the Routledge International Handbook of Sustainable Development (Edited by Michael Redclift and Delyse Springett) [51], offer useful summaries and identify new areas of emerging study on sustainable tourism development and management, such as climate change and climate justice.

3.3. Community-Based Tourism: Evolution and Intersections

Weaver [52] (p. 206) observed that community-based tourism (CBT) was referred to in the early 1980s as the sine qua non of alternative tourism. Hopes were especially high of combatting mass tourism in the developing world and aiding rural communities in the global south through grassroots development, resident participation, empowerment and capacity building (see Scheyvens [41,42]). Peter Murphy’s seminal book on community-based tourism [53], built on his research in the 1980s tourism in small communities in British Columbia and the Yukon (Canada). He advocated a systems perspective of community tourism where “community” very broadly refers to a group of people living in a defined space, and visitors interact with local people and landscape for a tourism experience ([50] (p. 188), [53])). We adopt his use of “community” for the purpose of this paper. Table 2 provides a few examples illustrative of the vast plethora of definitions and descriptions of CBT.

Table 2.

Community-based tourism (CBT): some descriptions and definitions.

Despite the wide-ranging and widely different, often divergent political and cultural spaces in which CBT practices occur, common ground can be found with respect to the objectives and intended benefits of CBT, such as community development, capacity building, local control and local enterprise development, sustainable livelihoods and poverty alleviation (see [55,58,60]). CBT concerns and cares remain highly local, and the long-term sustainability vision articulated by the global institutions of the north is neither the goal nor the driver of “sustainable tourism” at this local level: community development, community survival, community involvement and local benefit are among the foci here. Vajirakachorn [61] identified 10 criteria for CBT success in her study of rural communities in Thailand: community participation, benefit-sharing, tourism resources conservation, partnership and support from within and outside the community, local ownership, management and leadership, communication and interaction among stakeholders, quality of life, scale of tourism development and tourist satisfaction. Based on a more regional study that included a wide range of case studies of village tourism, community tourism and ecotourism practices in various countries in the Asia-Pacific, Hatton [62] concluded that while the implementation and outcomes of community-based tourism vary, common themes are present, such as economic gain, leadership, empowerment and employment (see also [63,64]. The main foci were economic and social well-being.

Environmental sustainability and responsible use and management of environmental goods are not generally seen as dominant priorities unless conservation is a key issue, as in the case of ecotourism and community-based natural resource management (see [65,66]). Fennell [33] in a content analysis of 85 definitions of ecotourism found seven most frequently- and commonly-used elements including: nature based, conservation, reference to culture, benefits to locals, education, sustainability and impact. Pro-poor tourism (PPT) is an important form of CBT that emphasizes poverty alleviation with a specific focus on increasing the net benefits of tourism to the poor. Its goals include raising income thresholds and quality of life for poor and marginalized groups through capacity building and creating sustainable and diversified livelihoods (see [56], [58], p. 9). More recently, fair trade tourism has added greatly to the local and social focus of CBT, bringing issues of justice and fairness to workers in addition to the natural environment. Strambach and Surmeier [67] present a CBT-type program with “Fair Trade in Tourism South Africa” (FTTSA), established in 2001, and believe it to be one of the first innovative service standards that emphasizes social sustainability. The objective of FTTSA is to facilitate “a fair, participatory and sustainable tourism industry in South Africa” [67] (p. 740). Fair tourism business is defined as one that complies with the principles of fair share, democracy, respect, transparency, reliability and sustainability ([67] (p. 740), [68]). Examples from the developed world offer similar perspectives [69,70,71].

Closely related to achieving the community priorities noted above is the crucial area of “community”-oriented governance. Empowerment and resident participation are considered essential [69,72,73], and a key principle of CBT is that development and use of the community’s goods and resources should be locally controlled, community-based and community driven. Yet, within the vast literature on CBT, while community involvement and resident participation are relatively ubiquitous principles, community ownership and resident control over decision making face significant challenges, and examples of CBT success are sparse. In a critical review drawing from various “community-based and -driven” development projects from around the world, Mansuri and Rao [74] offer valuable insight into the crucial political (and cultural) issue by carefully distinguishing community-driven development from community-based development:

Community-based development is an umbrella term for projects that actively include beneficiaries in their design and management, and community-driven development refers to community-based development projects in which communities have direct control over key project-decisions, including management of investment funds.[74] (pp. 1–2)

Scheyvens [41,42] identifies four dimensions of community empowerment: economic (income and employment related); psychological (considers community pride and self-esteem); social (community cohesion and well-being); and political (shift balance between the powerful and powerless, between the dominant and dependent, for greater political equity). Resident empowerment through tourism scales that were developed and tested in Virginia, USA, by Boley, Mcgehee, Perdue and Long [75] offers corroborative support for these economic, psychological, social and political empowerment dimensions. Table 3 summarizes a number of critical success factors (CSFs) for CBT that are understood to be common worldwide. These are organized under four key areas of community empowerment identified by Scheyvens [41,42] (see also [60,75]). The geographically-diverse scope of CBT spans the developing to the developed world (see, for example, [43,59,61,64,70]). Some scholars have identified additional criteria for inclusion that are generally not typical of CSFs, but important in terms of sustainability, tourism, as well as community well-being. These include environmental protection and management (e.g., community-based natural resource conservation) [66], infrastructure development [63,71] and direct control over the distribution of CBT benefits [74].

Table 3.

Some commonly-cited critical success factors (CSFs) organized under community empowerment dimensions provided by Scheyvens (1992/2002).

It should be noted that the CSFs listed in Table 3 are not fully comprehensive, but are representative of commonly cited CSFs in the tourism development and management literature. Numerous other criteria have been proposed less frequently for inclusion, such as environmental protection and management, infrastructure development [63,71], distribution of equitable benefits [74] and flagship or other significant (mega) attractions to support rural tourism development as a growth pole [70].

3.4. Comparing CBT to ST: Similarities, Differences and New Insights

The role of the local communities, while ambiguous or little emphasized in the institutional beginnings of SD and ST, became quickly evident in later initiatives like Local Agenda 21 and in various UNWTO documents (Figure 1 [21]). As Table 2 above shows, direct links have been made between ST and CBT. Some argue that ST principles are applicable to all forms of tourism, whether mass tourism, alternative tourism or CBT [21,46]. However, a careful comparison between the two raises important considerations for the development and management of tourism, ranging from conceptual and theoretical issues to issues of scale and size, as well as the engagement of the public/private sectors and the role of residents in matters of public good and societal well-being.

The literature review reveals a proliferation of stakeholders and interests in ST and CBT and a related abundance of definitions, criteria and principles related to sustainability. This makes good planning, implementation, management and monitoring problematic in the complex tourism system [48], both in research and practice. Conceptual and definitional challenges abound. Graci and Dodds [5] claim that there are over 200 definitions of sustainable tourism, without an internationally-recognized one. Weaver [7], for instance, championed sustainable mass tourism (SMT) to meet the visitor/destination demand and economic growth to be operationalized by applying three paths: (1) organic (spontaneous, market-led growth); (2) induced (mix of regulated and market-led growth); and (3) incremental (regulated) (CF [81]). Additionally, as in the ST literature, numerous definitions and approaches proliferate in the CBT literature, and little consensus appears to exist on the key principles of sustainability. While numerous certification and accreditations schemes have arisen in the context of sustainable tourism, ecotourism, rural tourism, etc., their effectiveness is inhibited by the primarily voluntary nature of these programs, lack of strong oversight and regulation and the global mobilities of transnational organizations, labor, capital, etc. [82]. Local resident control is seen to be a losing battle [83].

The scale and scope of tourism and the numerous stakeholders that drive ST and CBT make it extremely difficult to manage the local to global commons for environmental, social and cultural sustainability: good governance remains problematic at all levels from the local, to the global, and climate change and extreme weather will continue to exacerbate the challenges (see [84]). Initiated mainly by international public-private institutions (such as the United Nations’ Earth Summit, UNWTO, UNEP, WTTC and various tourism scholars especially originating in West-Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand), ST is generally conceived of on a larger scale than the local (historically regional/global). Its discourse is criticized as Eurocentric and overly focused on, as well as influenced by business interests [6,8]. By contrast, CBT has its origins in the local, focusing on grassroots development through participation, equity and empowerment and emphasizes local enterprises developed through local knowledge and entrepreneurship [43]. In the developing world, specifically the global “south” regions of Africa, Asia, South America, the origins of CBT can be traced to rural community development, economic and capacity building, social justice, poverty alleviation and community-based conservation, while economic considerations primarily drove CBT in the global “north” [6,8,29,85]. Similar to ST, CBT is also promoted by conservation, non-governmental, and international organizations, such as the World Bank and the Global Environmental Facility [86] (p. 2). However, it aims to maximize benefits for community stakeholders rather than absent investors, who may still be participants in ST operations, such as airlines, mega-resorts and chain-hotel investments. CBT initiatives are small enterprises. In this respect, CBT also overlaps with responsible tourism (RT) to seek an approach that “benefits local community, natural and business environment and itself” [87] (p. 314). CBT thus very clearly identifies with distributive and social justice, ethical relationships and equity, from its rootedness in the locale/community. CBT and ST thus reflect approaches with substantial intersections and overlaps, but also some significantly diverse foci.

However, as discussed further below, good governance is a significant challenge at the local level of CBT as much as at the larger macro-level ST discourses noted above. The political economy of tourism in the developing world, as Britton’s well-known article demonstrated, is driven by powerful external stakeholder, market capitalism and neoliberal interests [88] (see also [89]). Table 4 compares and summarizes some of the issues and challenges that face these two crucial discourses of sustainability.

Table 4.

ST and CBT: comparisons and contrasts.

3.5. A Closer Look at Some Key Dimensions of Sustainability

The review and analysis above reveal an important (and urgent) need to better integrate ST and CBT, for there are many similarities despite the difference of scale and priorities. Yet, even the priorities are not so dissimilar upon further examination, if one believes that individual and social well-being are integral to sustainability. The micro-level discourses of CBT help to “operationalize” some of the grander visions and goals of macro-level sustainability. Jamal, Camargo and Wilson [1] indicate the need for this as well. However, the vital role of governance at the community level is of crucial importance for successful CBT. How does this relate in the context of ST? Keeping this in mind, further examination of the literature gathered helped to identify a number of under-represented issues that ought to be vital to the success of ST development, such as governance-related issues that are clearly evident in CBT. Table 5 shows a comparison of key dimensions identified in ST. The last row in Table 5 summarized a number of governance-related concepts that have been discussed more broadly in the tourism literature without using the label of ST (hence, these did not show up in our literature review), but which are of relevance to considerations of good management and governance.

Table 5.

Some key ST dimensions and items that merit further consideration.

As the review conducted earlier in the paper shows, the literature is consistent with respect to identifying economic, social and environmental sustainability as key pillars/dimensions of ST (see [21,93,94,95]. Though the key dimensions remain the same, however, some specific details or extra dimensions are being added by other scholars and institutions over the years. For example, GSTC [27] adds one new dimension of sustainable destination management, which is missing in UNEP and UNWTO [21] and in the work of other scholars [93,94,95]. Moreover, all aspects of sustainability are not equally emphasized; some aspects have been mentioned by a few, omitted by many. Our examination of the literature also indicates that some important parameters are under-represented and poorly addressed in tourism research. For example, governance (institutional arrangements) has been mentioned by Bramwell [98], Roberts and Tribe [96] and Pukhakka, Cottrell and Siikamaki [97], with specific reference to sustainable tourism. García-Melón, Gómez-Navarro and Acuña-Dutra [101] mentioned government as a political/administrative dimension. Equity has been raised in the UNEP and UNWTO [21] aims and mentioned by Sharpley [47], Pomering, Noble and Johnson [100] and in FTTSA [68], but there is a paucity of good research on inequities in the distribution of goods, services and income and related issues of distributive and procedural justice. Jamal, Camargo and Wilson [1] also pointed out the need of a framework that emphasized justice and ethics as a new direction to sustainable tourism development. Jamal and Camargo [109] provided an introduction to destination justice that emphasized the need to address issues of equity and fairness. While they drew on Rawls’ theory of justice, they argued that it is inadequate to guide a just destination, and further research was needed to better identify guiding principles for destination justice. Inter- and intra-generational equity and equity among the nations of the north and the south is one of the objectives of the Brundtland report [16]. Unfortunately, benefits to disadvantaged groups through destination justice have been grossly neglected in many works, excepting a few documents, such as Guide for Local Authorities on Developing Sustainable Tourism [110] (p. 43), FTTSA [68] and the work of Lee and Jamal [108], who emphasized the need for procedural and distributive justice to the justice to the disadvantaged. The Mohonk Agreement [111] exclusively mentioned ethical issues in business operations, but progress in theoretical and empirical research is slow, as a number of authors have noted (see the last row of Table 5).

In the case of sustainable tourism development, many researchers seem content with presenting inter-relations among commonly-understood dimensions, such as economic, socio-cultural and environmental [22,93,94,95], and proposing criteria under these three dimensions. However, there are some like [27,28,96,97,98,99,100,101,112] who find institutional mechanism/governance/political administrative aspects to be critical for the success of ST/CBT and other alternative forms of tourism, such as ecotourism, rural tourism, responsible tourism, etc. Siow May, Abidin, Nair, Ramachandran and Shuib also recommended institutional framework criteria under the socio-cultural dimension [95] (p. 149). The governance-oriented scholars acknowledge the importance of institutional mechanism, whether formal or informal, networked or hierarchical, in achieving desired sustainable and community development goals. For example, in the 7Es of sustainable tourism planning (environment, economics, enforcement, experience, engagement, enquiry, and education) in Catibag-Sinha and Wen [113], the important role of governance is also denoted: enforcement and engagement. Ellis and Sheridan [114] emphasized the active role of government in bridging the theoretical and practical challenges that might arise between external stakeholders (academics, NGOs outside of communities) and local stakeholders (NGOs and communities), especially in lesser developed countries. Drawing from a case-study of Kumarakom, India, Chettiparamb and Kokkranikal [87] argued that besides voluntary codes of conduct by/for the tourism industry itself, some sort of regulation, enforcement and coercion is needed from the government in providing social equity and community well-being for responsible/sustainable tourism to be effectively operational. Wight’s [115] earlier study of the Province of Alberta, Canada, argued that an active government role was more effective in balancing tourism development goals harmonizing society, economy and environment rather than economic-focused goals led by the private-sector marketing body. Ottenbacher, Schwebler, Metzler and Harrington’s [116] examination of sustainability criteria in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, similarly showed strong support for government to conduct/implement sustainability checks for highly diverse tourism attractions in the state. These and other similar studies support the central idea that any framework, criteria or model of ST/CBT development remains incomplete without the inclusion of governance and its role as a facilitator and regulator of tourism development and management through active engagement and responsible partnership with the private and non-profit sector as needed.

In addition to the above, the literature review we conducted also revealed that sustainable tourism lacks a uniform definition and draws from many perspectives in defining its concepts, dimensions and approaches. Likewise, the processes of criteria and indicator development of ST and CBT have remained elusive. Numerous criteria and indicators of sustainable tourism have been forwarded that are at times highly ambiguous or contradictory, and the overall result seems to offer more confusion than guidance. We offer below a preliminary framework of “sustainable community-based tourism” to integrate and offer direction forward into an approach that bridges the local and the global and that situates sustainable tourism within the context of the local (in terms of place and community).

4. Discussion

4.1. Towards an Integrated Approach to ST and CBT

The review conducted thus far indicates that while some of the aims of ST and CBT appear to be similar (community and environmental health and well-being), there are significant differences and issues that are related to the spatial-temporal scale of this highly complex domain. Global issues of long-term planetary sustainability juxtaposed alongside local community/societal well-being require addressing diverse political, geographic and cultural contexts and stakeholders with varying interests and knowledge (public-private and non-profit, academic, residents, tourists, etc.). It is not surprising to see the plethora of definitions, principles and “success factors”, but the answer is not simply to continue business as usual, i.e., study and practice of ST and CBT as two different phenomena of long-term sustainability (ST) and local community well-being (CBT), as some might argue. Building on the previous section, this section teases out some of the more serious implications of the comprehensive literature review conducted above. A preliminary “synthesis” is then offered that may offer helpful directions forward to more effectively accomplishing mutually-desirable goals of the long-term sustainability of planetary resources and societal (including community) well-being.

4.1.1. The Global and Universal versus the Local and Particular

Following early drivers on sustainable development [16], a global vision and higher level of abstraction situated the emergence and development of ST, aiming towards common priorities of long-term planetary and resource sustainability along with other goals. Guidance (as most ST programs are voluntary) has generally been provided by global organizations and a number of smaller voluntary or non-profit organizations such as the NGOs, Netherlands Development Organization (SNV) and Tourism Concern. Global organizations include the UNWTO, WTTC, UNEP and GSTC, along with other institutionalized forms (such as national and regional governments, global certification programs, such as Green Globe, global advocacy organizations, such as Sustainable Travel International). While the UNWTO attempts global governance through mechanisms, such as the Tourism Bill of Rights, the Global Code of Ethics and various related committees and initiatives, none of these have regulatory “teeth”, and the tourism system continues to operate mainly on a self-regulatory system of voluntary efforts at responsible practices for sustainable tourism.

However, the challenges for sustainable tourism development do not end here. A variety of rights-based discourses are embedded in UNWTO documents, such as the Global Code of Ethics (see, for example, Article 6 on the right to tourism). Its own role is embedded in Article 3 in the Global Code of Ethics as developing and promoting tourism for economic development, understanding, peace, universal respect and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms. This puts it in a powerful position as one of the global moral arbiters of “sustainable” tourism, which, of course, is embedded deeply in a discourse of rights and ethics. As Smith and Duffy [104] and others have pointed out, however, the universal rights discourses that emanate from dominant institutions like the United Nations (e.g., its global human rights declaration) and the UNWTO are historically and culturally embedded in modernity, imperialism and colonialism, situated in the global “north” (i.e., “the West”). As various definitions of ST, CBT and the proliferation of goals, principles and criteria from the literature review show, the interests of Western, “developed” countries are oriented towards successful capital markets, profit and a use and development discourse embedded in instrumental use and material values of success and benefits (see Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 for examples). Universal, rights-based discourses tend to favor such ends, as exemplified by justice theories, just as that of John Rawls [117], that emphasize distributive justice in Western liberal democracies.

By contrast, the interests of the developing world tend towards very particular political and social concerns, such as self-determination, autonomy from colonial and other oppressive political regimes, capacity building and socioeconomic development. Such diverse cultural, geographic and political values and interests challenge the universalist ethics that attempt to institute justice and governance across the board, at all levels and all scales from the global to the local. In between the local and the global lies a disparate set of stakeholders, including national, state, regional governments and other public/private sector and non-profit organizations, including multiple levels of destination management organizations (DMOs) with each country (national and regional DMOs, local convention and visitors bureaus, etc.). Feminist critiques and other critical perspectives argue that “difference” is ruled out by dominant, universalist rights-based discourses. Individual agency, as well as community control are matters that must be negotiated not just at the international level, but also at the local level, if respect, recognition, equity and justice are to be enabled for diverse groups, cultural views, etc. Feminist theories, as Smith and Duffy [104] note, call for an “ethic of care” that addresses difference and the particular (local, individual, for example), rather than universal, generalized theories of justice.

4.1.2. Under-Representation of Equity and Justice

Despite the clear call for intra- and inter-generational equity in the Brundtland Commission’s global report on sustainable development [16], justice-related issues (e.g., distributive justice and procedural justice, rights of disadvantaged and diverse populations, minority ethnic groups in tourism destinations) have received limited attention in tourism studies [1] (p. 4605), but some momentum is beginning to gather (see [42,102,104,105,106,107,108,109,118,119,120,121]). Higgins-Desbiolles [106] argues justice tourism only as the true form of alternative tourism that has the capability of thwarting capitalists’ interests as “it seeks to reform the inequities and damages of contemporary tourism…to chart a path to a more just global order” [106] (p. 345). Justice tourism is described as “both ethical and equitable”, and it consists of attributes, such as that it: “(1) builds solidarity between visitors and those visited; (2) promotes mutual understanding, and relationship based on equality, sharing and respect; (3) supports self-sufficiency and self-determination of local communities; and (4) maximizes local economic, cultural and social benefits” [42] (p. 104). We draw from these authors to commence the discussion on equity and justice (Table 6), but much needs to be done in this knowledge domain. It is not surprising that Macbeth [105] proposed sustainability and ethics as the fifth and sixth platforms to supplement Jafari’s existing four platforms in tourism studies (advocacy, cautionary, adaptancy and the knowledge-based platform).

Table 6.

An integrated framework of sustainable community-based tourism (SCBT): dimensions and examples of criteria.

4.1.3. Bridging the Global and the Local: Towards a Preliminary Framework

The issues and barriers identified above point to an urgent need for a more robust framework that can address both ST and CBT from an integrated approach: neither ST alone, nor CBT alone are sufficient. The global environmental need for planetary sustainability that has driven the discourse of ST has to be reconciled or brought into better synergies with the local priorities of community control, capacity building, empowerment and sustainable livelihoods. The global imperatives of climate change and poverty alleviation call for urgent new directions and innovations to meet the interdependent priorities of planetary sustainability and sustainable livelihoods. However, the scoping review shows an overwhelming number of conceptions, definitions and descriptions of ST and CBT, forwarded by a diverse number of stakeholders worldwide. The field is muddied with confusing terminology, a cornucopia of principles that do not appear to differentiate management principles from moral principles. Overall, the development of effective sustainability-oriented frameworks, policies and practices appears to have proceeded in separate academic and practice domains with respect to both ST and CBT.

It is argued here that “sustainable” tourism development must be approached from an integrated macro-micro perspective, particularly in what appears to be increasingly globalized neoliberal development agendas [1,6]. As the above discussion indicates, issues of justice, equity and fairness in the distribution and use of tourism-related resources must be better addressed in the SCBT framework, both at the global and local level. Global governance and universal justice are needed, but so are local governance and attention to inequality, diversity and disadvantage at the local level. The UNWTO’s Global Code of Ethics and various industry-related codes of ethics and ecotourism/sustainable tourism certification programs have arisen and are important to enable some accountability towards responsible behavior. Such codes remain primarily voluntary and self-regulatory, as noted earlier. Guidance from global organizations and global non-profit organizations, certification programs and associations can help the “self-regulating” tourism operators and industry stakeholders with universal, generalized principles and criteria. However, the local must participate in enabling good governance at the local level, facilitating environmental stewardship, social justice, well-being and sustainable local livelihoods. Culturally-appropriate mechanisms for resident involvement in tourism development, planning and decision making are needed that enable local control and good governance, ensuring justice, equity and fairness in the use and distribution of tourism goods. Principles of sustainable tourism in general include: (1) taking a holistic view; (2) pursuing multi-stakeholder engagement; (3) planning for the long-term; (4) addressing global and local impacts; (5) promoting human heritage and bio-diversity; (6) preserving essential ecological processes; (7) ensuring equity; and (8) supporting local communities [6,21,44]. Such principles are helpful to local level community-based enterprises and community development goals in CB. However, weaknesses in the implementation of these principles, whether owing to poor linkage or lack of effective governance and attention to issues related to justice, ethics and equity, remain a major obstacles. The integration of these principles into a framework of SCBT that supports the established environmental, social and cultural criteria with clear, strong emphasis on governance, justice and ethics (Table 5) is a crucial endeavor if major sustainability challenges (such as climate change that threaten further inequities and injustices to the poor and marginalized) are to be effectively addressed.

Table 6 and Table 7 together offer a preliminary framework for SCBT based on the scoping review. Key criteria and items common to ST and CBT that were obtained from the extensive literature review are listed as examples under the economic, environmental/ecological and social-cultural dimensions (see the second column; pertinent authors/sources are shown in the third column). All of the criteria and items in the second column of the framework are adopted from the authors/sources cited. However, to provide more legibility and uniformity to the framework, we have invented broad sub-headings (in bold) in the second column under which various criteria and items have been grouped.

Table 7.

Governance and underrepresented issues in the domain.

The literature reviewed above shows some ubiquitous goals and criteria that are common to both CBT and ST. Some governance-related items are consistently mentioned (e.g., local participation in decision making is a key principle of CBT and is noted by UNWTO for ST. However, the mantra of local control and resident-driven decision making in CBT tends to be problematic, as local governance is shaped and influenced by diverse historical, political, cultural and ethnic values. Capacity building, a key tenet of CBT, is also a challenging goal to accomplish if local residents and stakeholders are not empowered in matters of governance, to obtain, control and direct the use of goods and services towards broader sustainability oriented goals, such as long-term environmental conservation, community well-being, etc. A greater focus on “good governance” at the local level is therefore needed in the integrated SCBT approach.

Issues of equity, fairness and justice were found to be surprisingly under-represented in the literature review (one wonders why, as sustainability involves issues of fairness, historical injustices, trade-offs and distribution/use of often limited, non-renewable resources, etc.). We make a start to address this in Table 6 and Table 7. In order to emphasize the under-represented domain of governance and justice drawn from the literature, these are presented separately in Table 7 below. They offer the potential to bridge the global discourse or ST and the local discourse of CBT, by bringing together universal and rights-based discourses (e.g., distributive justice, procedural justice) with local, particular issues (including historical injustices to specific groups), situated justice and an ethic of care and attention to diversity and “difference”. In this sense, it can be argued that justice enables a crucial bridge between the global and the local, the universal and the particular. Issues of tourism development involve ethical issues of equity, fairness and justice in enabling global, planetary sustainability and local, community well-being.

5. Where Do We Go from Here? Directions Forward

While preliminary, the notion of SCBT proposed in this article offers some important avenues to direct future research and practice in this area. The work summarized above reflects the history of ideas in the evolution of sustainable tourism and community-based tourism. It reveals a complex terrain of conflicting terms, concepts, principles and values and a vast number of criteria that have occupied researchers and practitioners. Yet, a close look at the information presented above offers strong justification for an integrated approach to ST and CBT, i.e., sustainable community-based tourism. The greater focus on environmental sustainability that the concept of sustainable tourism inherited from its roots in sustainable development has been slowly offset with increasing attention to social and cultural impacts of tourism development and to the economic and overall well-being of local communities. The scale of sustainable tourism has evolved from global discourses (e.g., of UNWTO, UNEP [21]) to implementation by various organizations and destinations at the regional and local level worldwide, with policies emerging at the country-level in some cases, like Australia (e.g., [136,137]). Meanwhile, despite a strong focus on community development, growing awareness of the need to manage community commons, environmental health and conservation of natural goods is enabling a longer-term sustainability horizon to be incorporated into various CBT practices and forms (consider community-based ecotourism, for instance). Similar efforts have arisen with respect to the principle of equity in ST and CBT. Community-oriented tourism initiatives, like CBT, while presenting some similarities to sustainable tourism, also espouse some distinctly different, vital development goals (Table 5). As Saayman and Giampiccoli [138] put it, as an alternative to conventional mass tourism, CBT emphasizes control by community members, and the tourism-related benefits are intended to address economic disadvantage and social justice. Variants of such community-focused approaches, like pro-poor tourism (PPT), are specifically focused on redistributive aims and, as Butler, Curran and O’Gorman [56] show with their study of PPT in the regeneration project of Glasgow Govan (U.K.), are applicable to both the developed and developing world. Butler et al. [56] argue that government should be enforcing PPT principles rather than leaving this to businesses or other enterprises. The differences between ST and CBT thus begin to diminish in terms of geographic scope as examples arise of both forms around the world and with the inclusion of local resident communities as key stakeholders in ST [44,139]. This seems to be a good base from which to bridge the macro-micro, local-global scale and complexity of the tourism system, and Table 6 and Table 7 appear to be a reasonable starting point to commence the task of developing an SCBT framework to inform development, planning and management.

However, in going forward, there are some critical issues that our historical exploration above have just begun to reveal. Some repeated concerns and issues raised by previous researchers might be resolved through an integrated framework. For instance, Cardenas, Byrd and Duffy [140] summarize well about the importance of a good knowledge base among residents and other stakeholders who are invited to participate directly in tourism development, planning and management, facilitating important principles related to local control and the fair distribution of tourism resources and benefits. “Before informed, active, full, or meaningful participation can be achieved, tourism planners need to evaluate stakeholder level of awareness and perception of tourism, the tourism process, impacts, and principles of sustainability”(p. 254). They develop a tool called the Sustainable Tourism Development Index (SUSTDI) to assess the stakeholder (including community groups) awareness of tourism impacts and their perspectives on sustainable tourism development principles. Yet, despite all of the progress made over the last few decades in addressing crucial issues of environmental and social sustainability, individual, societal and industry well-being, concerns about the usefulness of the ST- and CBT-related concepts and failures of implementation abound across the globe remain. Three areas of pressing concerns are highlighted below, building on the history of ideas in sustainability-oriented and community-based approaches to tourism laid out above and which we believe are crucial to address if the proposed SCBT framework is to be successful. By itself, it too may result in inconsistent results and continued muddling through mazes of disparate views, values and approaches in tourism research and practice.

5.1. In the Grips of Neoliberal Globalization: The Primacy of the Local, the Failure of Academia

Bramwell and Lane [141] in their special issue on Governance in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism note that “tailored and effective governance” is crucial for implementing sustainable tourism, enhancing democratic processes, providing direction and facilitating practical progress. They argue that theoretical frameworks are crucial. One of the most strikingly obvious yet immensely puzzling observation that has arisen from our exploration thus far is not only the lack of theoretical guidance, but also the systematic failure to progress from critiques and calls for local control and community involvement in the literature, to a clear understanding and implementation of “good governance” in theory and practice. Ruhanen [142] undertakes a study of the transfer of academic knowledge on sustainability to tourism public sector practice in five destinations in Queensland, Australia. Her results indicate a knowledge-practice, gap, i.e., that the knowledge based on this topic in academia has not been diffused effectively to planners and managers. Dredge and Jamal [143] adopt a poststructuralist approach to their study of planning and policy studies in tourism. Their findings lead them to conclude that “mainstream subjects related to destination development and management dominate while critical analysis of economic and political structures, interests and values is lagging” and tourism planning and policy studies must progress “towards greater visibility, legitimacy and importance in tourism studies through more critical engagement with tourism public policy and planning practice”.

However, in almost three decades since the release of the Brundtland Commission’s report on sustainable development, and more than that since the rise of RT and CBT, a “critical” engagement with the role of the public sector power, empowerment and control over the use and distribution of the public commons, long-term sustainability of environmental and social-cultural goods and planning and management practices have resulted in little shifting of power and “community-driven” tourism continues to occur in small pockets at best, with calls worldwide for greater integration and engagement of the public sector. Zou, Huang and Ding [144], for instance, forward a community-driven development (CDD) model in China for which they believe “theoretical implications could be derived from this paper to direct tourism planning exercises in other countries, especially those developing countries with similar economic development backgrounds to China” (p. 261). Their model is oriented toward three key factors: localization of the supply chain, community-external investor symbiosis and democratization of decision making. Zou et al. [144] observe that the “Manila Declaration on the Social Impact of Tourism”[139], “promises to maximize the positive effect of tourism through extensive community participation…Maintaining local control is also one of the important principles advocated by WTO in developing tourism” [144] (p. 263). Acknowledging that government reforms in China still had a long way to go, they believe the CDD model of rural tourism is an optimal way for sustainable rural tourism development in China and needs to be institutionalized and recognized in the government policy agenda. Their insights, like those of other academics addressing sustainability and tourism in and from post-colonial democracies, as well as post-socialist, post-communist and post-apartheid contexts, speak to the importance of focusing greater attention on the role of the public sector, from the national to the local level (see, for example, [145,146]). In keeping with other proponents of poverty alleviation, Chili and Xulu [145] feel strongly that “government at all levels has the obligation to ensuring that the plight of the poor is addressed and turned around through sustainable tourism development” (p. 27). They, note, too that:

Overall, there limited literature that explores the role of local governments to facilitate and spearhead sustainable tourism development especially in developing countries (Yukdsel, Bramwell, and Yuksel [147]). In most cases governments tend to have numerous and promising policies and plans for sustainable tourism development which unfortunately do not yield good results because of deficiencies and shortcomings on execution and implementation.[145] (p. 27)

The gap between academic research and practice and the continued lag in both planning and policy to instantiate the common accord in ST and CBT for local control, resident involvement and resident participation in tourism is troubling. However, even more worrisome is the lack of attention to the commonly agreed on principles of local control, oriented especially towards social justice and fair distribution of tourism goods and benefits to local residents, including diverse populations and disadvantaged groups. While a SCBT-based approach seems favorable to addressing the various spatial and temporal aspects noted above in the complex tourism system, how well can it address this continuing lag, which is especially worrisome in the present-day context of neoliberal globalization? Saayman and Giampiccoli [138] offer a succinct analysis of the current neoliberal milieu, concerning matters of poverty reduction and community development. As they note, within this context “specific issues of ideology, discourse, policies and related matters in general and their correlation to tourism need to be considered and sketched out” and, furthermore, “effort should be made to scale-up CBT concepts and practices to have greater impact. There is no conceptual or practical restriction to the scale-up of CBT development. Effective global restructuring of the tourism system cannot be on small scale” (p. 164). Their argument for scaling up from the micro-local to the macro-global level bodes well for an integrated approach to SCBT, but the continued failure of tourism studies to tackle tendentious political and ideological issues related to tourism policy and planning is highly problematic and deserving of much closer scrutiny and efforts to engage in academic praxis in the face of a global neoliberalization of local-global environmental and social systems. Dredge and Jamal [143] reiterate this call for greater academic attention, especially in light of neoliberalist shifts from public administration to public management over the last few decades:

…from the 1980s onwards, neoliberalism, globalisation and new public management have prompted a downsizing and outsourcing of government functions and a move away from direct government involvement in economic and social affairs. The role of government has been recast as a facilitator and enabler of economic activity…This shift is described as a move from public administration to public management, and has been characterised by the increasing uptake of public-private partnerships, collaborative planning and policy development and government- business power sharing (Bramwell, and Hall [98,148]). It has also meant that governments’ relationship with public interests has become increasingly blurred… the notion of an overarching set of collective public interests for a broad and encompassing public good has been progressively abandoned by government policy makers in favour of a neoliberalist view….[143] (p. 287)

5.2. What Are “Good” Principles for SCBT?

Table 6 shows an integrated set of criteria that are commonly cited under the well-established dimensions of environmental, social and economic impacts in the comprehensive literature review that we undertook. Table 7 shows some criteria, the additional dimensions of governance, justice and ethics, which are integral to development and sustainability goals. We use criteria here intentionally, as this was the most common item used in ST and CBT studies, from which we are able to compare and note similarities and differences between the two concepts. Closer attention is needed to clarify and reduce ambiguities in future research and to ground ST and CBT in a clear framework of ethical and management principles; both kinds are cited, but management principles in the context of environmental, societal and individual sustainability (in addition to economic and business sustainability) are grounded in ethical principles, though they may not be evident. The field of tourism studies in the 21st century can no longer ignore the global, but interrelated issues of environmental degradation, human disadvantage, poverty alleviation and climate change and clear ethical principles to guide research and practices are imperative. Developing such a framework of ethical principles for an integrated approach to the development and management of tourism at the local-global level is of vital importance. By bringing ST and CBT together as SCBT, it may be easier to undertake the task of grounding the complex tourism system in ethical principles that inform good governance, good practice, good management and good tourism (see Levy and Hawkins [149]).

It should be noted here that, as mentioned earlier, the array of concepts, terms, criteria, indicators and principles cited in the literature have tended to overlap or be confused in the meaning of each term. The Scopus literature review revealed a significant gap with respect to identifying key ST and CBT principles used by researchers. Other than commonly-known ones, such as noted earlier in the article (e.g., sustainable tourism development should be equitable in meeting the needs of current and future generations of tourists and residents; local communities should have control over tourism decision making in CBT; or a PPT principle that tourism benefits should be distributed to the most disadvantaged in the community), the principles are inconsistent , vague or hidden within general criteria, which are then used as “principles” (see, for example, Helmy [150], who aims to use ST principles in the research, but then switches to using ST “criteria” later).

What constitutes “good tourism” seems to be enmeshed in a swath of constructs with little agreement about these among academics or practitioners, and philosophical or theoretical guidance has been highly limited. Moscardo and Murphy [151] argue that “[w]hile the management of tourism impacts and the relationship between tourism and sustainability have been paid considerable attention by tourism academics, there is little evidence of any significant change in tourism practice” (p. 2538). To them, it reflects problems in the way tourism academics have conceptualized sustainable tourism, and they offer an alternative framework that addresses “quality-of-life, recognizes the complexity of tourism within local and global systems, adheres to the principles of responsible tourism, and explicitly assesses the value of tourism as one tool, amongst many, for sustainability” (p. 2538). Yet, what principles and capacities help to enable “quality of life” can vary significantly, and theory building is desperately needed to address moral questions about the good life and good tourism that could help ground sustainability principles, environmental and community well-being and individual quality of life in relation to tourism [104,152,153]. A limited number of studies have arisen to evaluate the success of sustainability in tourism-related endeavors using planning and management tools that draw upon key ethical theories (see, e.g., [92,154]).

5.3. SCBT Guided by Justice and an Ethic of Care?

Whitford and Ruhanen’s [137] study of Australian State/Territory governments’ policy for indigenous tourism examines how sustainable development principles are addressed and finds a “sustainability rhetoric” with little success in achieving sustainable tourism development for indigenous peoples. Based only on this study, the authors state that “one size fits all” framework for indigenous tourism development cannot work, and “policies need to draw upon indigenous diversity and, in a consistent, collaborative, coordinated and integrated manner, provide the mechanisms and capacity-building to facilitate long-term sustainable indigenous tourism” (p. 492). Little is mentioned of the historical context of indigenous oppression and possible structural conditions that continue to embed possible discrimination and racism, historically, in the Australian post-colony. Manyara and Jones [59] feel that the failure of CBEs in Kenya is related to foreign resource control and heavy reliance on donor funding that instantiate dependency and neocolonialism. However, how effective will their call be to integrate principles of sustainable development into community tourism development in Kenya, empower local leaders and communities and implement appropriate policy frameworks, if structural and institutional conditions that facilitate dependency and underdevelopment are not addressed? This calls not simply for radical inquiry into political issues and areas that, with some exceptions, scholars in tourism studies appear reluctant to tackle. Critical tourism studies have emerged as a young field of inquiry, and a small, but growing base of critique is emerging on topics such as neoliberalism, political economy, political ecology and “sustainability” in tourism (see, for example, [88,155,156]).

In an era of neoliberal globalization and severe challenges of climate change, tourism researchers and practitioners are being increasingly faced with issues of local and global justice, historically-driven inequities, structurally-embedded discrimination and institutional racism. Justice-related matters are just being taken up in tourism studies (see the studies mentioned in the previous section related to environmental and social justice), but much needs to be done in the context of sustainability and community-based tourism (SCBT in our case). Jamal and Camargo [109] forward a perspective on “destination justice” that calls to supplement Enlightenment- and modernity-driven notions of distributive justice used by Western liberal democracies (see, for instance, Rawls [117]) with an “ethic of care” drawing from Aristotelean and feminist perspectives for a more situated justice based on virtue ethics and care.

6. Conclusions