Abstract

There can be little doubt that sustainability has become one of the most important issues in business in recent years. In spite of sustainability’s importance, there is agreement amongst leaders and practitioners that sustainability is not as embedded as desired. This study reports a framework on inhibitors that limit sustainability embeddedness in organizations. The framework can assist management to address the non-achievement antecedents of embeddedness specifically and holistically. This study obtained empirical data from employees on all management levels in a stock exchange-listed company. Through in-depth analysis in a case organization, valuable insights about embeddedness were inductively identified, interpreted and presented using descriptive labels, namely: “Professing What Is Right”; “Green Distraction”; the belief of “Not My Job”; “Firefighter”; the “Past Performance Anchor”; “Strategy Discourse” and “Harmony”—a mediator to sustainability embeddedness. All these were also found to be altered by the transformation of culture and the communication of the strategy message by sustainable leadership—the moderator. The findings were also corroborated by related and supporting literature as part of our contribution and pursuit for better understanding of this phenomenon.

1. Introduction

There can be little doubt that sustainability has become one of the most important issues for business in recent years. For corporates, sustainability refers to the business of staying in business and is associated with organizational resilience and performance [1,2,3]. We see evidence of the importance of sustainability in industry debates and reports, in academic journals—including special issues such as this—and in governance policy. Sustainability calls for a deep-seated transition from business-as-usual towards revisited organizational mechanisms and revised practices and strategies that are embedded with sustainability [4,5]. Despite sustainability and its strategic importance to business being a well-supported idea, most agree that there are challenges regarding its embeddedness and implementation [6,7,8].

2. Theoretical Background

Sustainability (often referred to as sustainable development or corporate sustainability) is generally accepted to be the internalization of social and environmental concerns into business operations and in interactions with a wider group of stakeholders [9,10]. It also extends to larger concerns such as equity, governance and social justice [11]. Sustainability supports the idea of an integrated value creation space, where growth and performance for the current generation pays equal and simultaneous consideration to all the elements of sustainability and to future generations [12,13].

The adoption of sustainability by organizations is a popular topic because of its potential to serve the common good [14]. Sustainability adoption is associated with an organization’s great potential to make a positive contribution to sustainability issues and to enhance corporate sustainability performance, competitive advantage and organizational resilience [9,10,15]. The sustainability embeddedness journey is appealing and there are numerous potential benefits that derive from sustainable practices. Some of the benefits include: potential cost savings; enhanced reputation; increased innovation; competitiveness and employee retention; the creation of valuable and rare resources and capabilities; and reduced risk [9,16,17,18,19].

Various authors have contributed to the clarification and conceptualization of an organization’s progress and adoption with regards to sustainability [9,14,20,21,22]. Sustainability adoption is often described in phases or stages on a continuum that is associated with operational and paradigmatic milestones. The stages of sustainability adoption can be broadly grouped into three orientations, namely: a reactive orientation; a proactive orientation; and a sustainability-embedded orientation. A reactive orientation refers to an organization’s response to changes in environmental and social regulations and stakeholder pressures through defensive lobbying and investments in end-of-pipe environmental measures such as retrofits [21,23]. Reactive organizations are more focused on liability than responsibility with regards to sustainability. They mostly ignore the notions of sustainable development, or, at the minimum, reactively respond by doing only what they are legally bound to do [9]. Reactive organizations typically operate from Compliance stages of sustainability adoption and have a short-term perspective in business [21,22].

A proactive orientation refers to the purposeful way an organization anticipates future regulations and social trends, and the way they design or alter operations, processes and products to prevent negative environmental impacts [14,20,24]. These organizations mostly operate in the Beyond Compliance and Integrated Strategy stages [21] or Efficiency and Strategic Proactivity [22] stages of sustainability adoption. Organizations in these stages typically develop a commitment to sustainability and aim to make it part of their strategy [25]. This decision often leads to the initiation of multiple environmental and social projects such as waste reduction, energy saving or HIV−Aids awareness programs [9,26]. These projects are sometimes sporadic and the focus is on the direct or indirect cost-saving benefits or investment opportunities associated with sustainable projects [9,25,27]. Proactive organizations characteristically manage their sustainability initiatives from specialized departments or functional areas [25,28]. Proactive organizations see external engagement with stakeholders as an integral part of strategy but their focus is more “inside-out” and they may still favor shareholders [9,10,14]. Proactive organizations generally prepare internal and external sustainability reports and establish, or affiliate themselves with, environmental and social committees [20,21].

Scholars have struggled in the past to distinguish between the proactive and sustainability-embedded orientations. Valente [20,25] notes that the absence of clarity between the orientations has resulted in many corporate activities being grouped together in the proactive paradigm [2,29]. The sustainability-embedded orientation refers to sustainable organizations that have undergone a paradigmatic shift and adopted firm-wide sustainability embeddedness so that sustainability has become an organizational way of life [9,20,30,31,32]. This means that sustainable organizations have embedded sustainability in their business models and strategies, operations, governance and management processes, organizational structures, culture and in their reporting [9,14,33,34]. Sustainable organizations generally have formal committees addressing sustainability that include senior executives and various stakeholders, and sustainability departments addressing sustainability that are integrated into the organization structure [25,35].

Sustainable organizations normally operate in the Sustaining Corporation [9,36] and Purpose and Passion stages of sustainability adoption [21]. Dyllick and Muff [14] describe truly sustainable organizations as those who have shifted from seeking to diminish the corporates’ negative impacts to understanding how it can create a significant positive impact in critical and relevant areas for society and the planet. Sustainable organizations have the ability to integrate seemingly diverse aspects of sustainability into their immediate environment [25]. The focus is on the equitable inclusion of a highly interconnected and interdependent set of social, ecological and economic systems [20,21]. When sustainability is embedded in the organization, it should be reflected in the continuity of sustainability projects and practices as opposed to ad hoc efforts [9,20]. Sustainability projects are also considered to be the beginning point of collaboration and not the end point [25]. Truly sustainable organizations maintain an “outside-in” focus to their stakeholder engagement. They collaborate with a wider group of stakeholders, as opposed to only engaging with shareholders [10,14,25,32]. Embedded organizations understand that their relationship with stakeholders in their surrounding context is critical for survival [25]. The top management of embedded organizations focus on combining and developing complementary capabilities amongst practitioners, and the company often enjoys sustainable competitive advantage because of the development of valuable and rare knowledge stemming from employee and stakeholder relationships [20,25].

In this paper we define and conceptualize sustainability embeddedness as the instilling of sustainability into practices (behaviors, actions, beliefs and attitudes) at every level [7,17,37] so that they become deeply engrained in the organizational existence (strategy fabric) and an integral part of how the organization ensures its future resilience and performance [9,15,38], eventually leading to a change of the organization’s culture towards the long-term sustainability of profit, people and planet [1,17,39]. Sustainability embeddedness calls all members, across all functions and geographic locations of an organization, to undergo a paradigm shift towards sustainability and towards becoming a sustainable organization [15,20,40,41].

While sustainability embeddedness literature is an interesting and insightful area of research, it has also received criticism, and poses challenges for organizational leaders, practitioners and researchers. The idea of an organization fully embedding sustainability is criticized for its heavy reliance on organizational leaders as “culture creators” tasked with fostering shared sustainability beliefs, commitment and values amongst practitioners [15,17]. Literature refers to these leaders as sustainable or responsible leaders [1,10,42,43]. Sustainable leaders are those that seek to instill behaviors, practices and systems that create enduring value for all stakeholders of organizations including investors, the environment, other species, future generations and the community [44]. Sustainable leaders are committed to transforming organizations into sustainable organizations by embedding sustainability into the culture through sustainable leadership practices [17,45,46]. Their principles and attitudes differ significantly from the traditional “locust” leadership which focuses on getting the most profit out of business and serving shareholders first [1]. Critics of sustainability-embeddedness literature purport that organizations have subcultures that consist of members who hold different attitudes and beliefs towards corporate sustainability and that these may be irreconcilable with those of the organization [15,17,47]. The existence of subcultures is believed to hinder the diffusion of a unified sustainability culture that shares a common set of sustainability values and beliefs [1,10,15,47]. Critics of embeddedness literature challenge the belief that sustainable leaders can create a single, widely shared culture for sustainability and suggest that they should rather accept that practitioners hold different attitudes and beliefs towards sustainability [1,17].

A commitment to becoming a sustainable organization also poses challenges for organizational members that are required to undergo a deep-seated transition in their decision-making for sustainability [32]. It means that practitioners need to depart from their old ways of prioritizing the economic dimension of sustainability over the other elements (known as a business case view) which may previously have been common practice in the reactive and even proactive orientations of sustainability [20,27,48]. Instead, practitioners need to simultaneously, integratively and equitably include all the elements of sustainability into decision-making (an integrative view). This view means that practitioners need to accept and manage the inherent tensions between the seemingly contradictory yet interrelated economic, environmental, and social concerns [25,27]. The shift to embeddedness calls for organizational members to synthesize their worldviews and strategies and resist dismissing situations where social and environmental aspects cannot be aligned with financial outcomes [20,31,48,49]. The journey to embeddedness entails that all those involved arrive at a workable balance between sustainability objectives and deal with the “chasm between business and the environment,” which can be difficult [31,48,49]. Researching sustainability from this integrative perspective has not been widely studied and even fewer studies have been practice-based [25,32,48]. This may be because this perspective for research is considered the “ultimate challenge of research on corporate sustainability,” thereby highlighting the importance of this study [27,31].

3. Research Purpose

The reality is that the journey to sustainability embeddedness for organizations is complex and multifaceted [7,8,50,51,52]. In spite of evidence that sustainability embeddedness is a legitimate and accepted orientation for business, leadership’s commitment to realizing it, and the existence of many frameworks and tools—it appears that sustainability has been found to not be as embedded as desired [8,27,53,54,55,56]. In fact, authors Hallstedt et al. [4], citing Willard [57], note that few companies have progressed to the Integrated Strategy or Purpose and Passion stages of sustainability adoption.

Literature and industry studies stress a persistent gap between aspirations and action when it comes to sustainability adoption, and refer to challenges with embeddedness [2,4,6,19,58,59,60]. This is because embedding sustainability is not a trivial task, made worse by the fact that there is uncertainty about sustainability’s interpretation, and lack of consensus regarding its definition [6,7,61].Notwithstanding these realities, Nambiar and Chitty [6] note that “little has been done to more deeply investigate the limiting issues that may be contributing to this gap” or to provide insight into why organizations are still struggling with sustainability embeddedness [7,8,20,48].

Scrutiny of the literature reveals that most studies have focused on exploring the antecedents to, and the consequences of, proactive orientations of sustainability adoption. There are limited studies that have departed from the proactive orientation towards the adoption of a sustainability-embedded orientation [15,20,23,26,40]. Studies have also tended to focus on the operational changes required by organizations—such as strategies for reducing waste—often neglecting to examine organizations holistically in terms of both the operational and transformational changes required to shift to embeddedness [17,20,26,28,43,62].

In the spirit of these gaps, this study sets out to explore the transitional space between proactivity and sustainability embeddedness. In this space, we seek to better understand and conceptualize the limiting issues that inhibit the shift to embeddedness. We aim to provide insight for leaders and managers into why organizations are still struggling to embed sustainability, thus revealing the fundamental gap and the purpose of this research. To do this, we posed the following research question: What are the limiting issues that inhibit sustainability embeddedness?

To answer this research question we identified a case company that aspires to become a sustainable organization, but currently exhibits characteristics associated with the proactive orientation phase of sustainability adoption [14,20]. Individual and focus group interviews were used to gather data and explore sustainability embeddedness at all levels of management in the company. This study aims to empirically build theory by interpreting data from semi-structured questions by means of an inductive analysis using elements of grounded theory [8,63,64]. Findings contribute to the identification of the limiting issues and the development of a conceptual framework which we hope will guide and support management. After the interpretation of the findings, we used existing and related literature and theory to confirm and challenge our findings (theory testing), so as to advance the discussion on sustainability’s embeddedness [65,66].

4. The Case Study Context

One of the key features of sustainability research is the value of contexts [67]. The context from which the limiting issues of sustainability embeddedness emerged was a single case in South Africa that exhibits the characteristics associated with a proactive orientation of sustainability adoption [23]. The case context is a developing country which is known to have environmental issues and large social inequality [68,69]. We believe the context of this study adds value to the findings because it is recognized that organizations in developing countries have increased responsibilities in terms of public welfare [20,27,70].

The phenomenon investigated is how practitioners think and act towards making sustainability-embedded decisions and practices (or not) in their jobs that influence organizational aggregate sustainability adoption and embeddedness [60,71,72]. The case company chosen is a property company that owns, manages, develops and refurbishes a large portfolio of retail, commercial and industrial properties. The case company is a leader in its industry and a stock exchange-listed company on the Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) South Africa. Leadership at this company has made public statements indicating their commitment to sustainability (on websites and in reporting) and has made reference to their journey of sustainable development that influences the way they do business. On a strategic level, leaders have revised the organization’s value creation process to incorporate various strategic levers to integrate sustainability. The case company has demonstrated sustainable practices, including a green amendment to their leasing contracts to save electricity, and they have set clear targets as a company for carbon-emission reductions, energy efficiency and water saving. The case company also strives to follow the Green Building Council of South Africa’s standards and ratings of buildings, and has won numerous awards for greening, social initiatives, and reporting. Currently, the case company has executive-level representation for Corporate Social Responsibility and staff formally employed to implement sustainability initiatives such as lighting retrofits and community development projects. The case company’s public commitments and reported sustainable practices were analyzed as part of a study by Pretorius and le Roux [55]. The study determined the status of sustainability embeddedness in strategizing, of the top 40 listed companies on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, using a measurement tool applied to publicly available information. The case company’s rating demonstrated that it has made sustainability part of its strategy. As such, we believe that this case company presented a particularly unique and information-orientated position for research and supported us in answering the research question [64,73].

5. Methodology and Data Collection

After identifying the case company, we engaged with it’s top management to discuss sustainability adoption and embeddedness. Engagement revealed anecdotal evidence or signs confirming a prevailing management dilemma. These signs were that managers observed that decision-making processes amongst practitioners did not always reflect a balance between the elements of sustainability and that company risk assessments are not always reflective of an integrative view of sustainability. Furthermore, decision-making outcomes have been found to not always mirror the consideration of broader stakeholder groups. There was a general concern by top management that sustainability may not be as embedded as desired despite their commitment to become a sustainability-embedded organization. From this meeting we were able to establish a need for the research in practice, and obtained permission for the study.

Given our pursuit to better understand the limiting issues of sustainability embeddedness, we embraced a qualitative approach using elements of grounded theory [63,74]. Sustainability is widely considered to be a complex and value-laden topic which some argue is more suited to qualitative and holistic approaches [53,60,73,75]. Grounded theory is also appropriate for researching sustainability embeddedness in contemporary contexts [17,20,62]. Our approach supported us in gathering rich in-depth descriptions from participants, which assisted us in answering the research question [63,64]. The study included a total of 56 practitioners (employees and participants in the study) from all management levels, geographic locations, functions and divisions. In general, sustainability has been investigated among sustainability “experts” or the “corporate elite,” thereby focusing on the views of specific management levels or departments [6,11,34,58]. Our goal was to gather a representation of diverse views around the topic of sustainability at the organization. Our decision was motivated by an understanding that sustainability embeddedness is a diffusive process that should occur across the entire organization [9,20,41,62]. Additionally, it is known that individual actors outside top management have critical roles to play in promoting and implementing sustainability [76,77].

We conducted 15 individual interviews of approximately 1.5 hours each, where ample time was set aside for explanation, elaboration and discussion. The interviews were voice recorded and transcribed by a professional transcriptionist, and participants were assured of confidentiality and their rights where necessary [78]. Additionally, 36 practitioners participated in five focus group interviews. The focus group interviews had the same inclusion criteria and similar questions to the individual interviews, but the questions were phrased to suit a group dynamic.

To collect data, we made use of an interview guide that we created from available related literature on the topic. The interview questions were semi-structured and sought rich descriptions that supported us in construct development and the conceptualization of the limiting issues [63,74]. At the start of the interviews we asked practitioners about their understanding of their roles and responsibilities, as well as the daily and strategic decisions made in their jobs and the factors and criteria influencing their decisions and practices [75,77,79]. We also made use of sensitizing concepts as points of departure for discussion and further questioning [63]. We were interested in practitioner opinion, understanding and practices regarding the interrelated topics of: strategy; performance; risk; leadership; sustainability and integrated thinking [4,33,34,38,42,80,81]. We spent time discussing practitioner views and descriptions associated with sustainability and its relation to their jobs and the organization as a whole [17,26,37]. We then asked the participants how they would describe sustainable decisions and what challenges they may face in making these decisions [15,27,51]. Data was collected cross-sectionally and analyzed over a six-month period, but the study’s preparation and development took more than two years. This time-frame allowed for interim data analysis between data collection and corroboration to ensure a match between the findings and the participants’ perceived reality [63,82].

After the data had been analyzed and conceptualized, we engaged in theoretical sampling, which is a distinctive feature of grounded theory [63]. The purpose was to clarify and substantiate emerging categories for conceptual and theoretical development and to subject the initial data to further empirical inquiry. Our focus was not to gather quantitative data for analysis, but rather to gain a form of “conceptual weighting” and support (or not) for the findings. We also wanted to determine if any aspects were overlooked, thus ensuring credibility. We arranged a sixth focus group interview with an additional five practitioners using a revised interview guide and different inclusion criteria. None of the practitioners in the group was part of the previous interviews; however, all the practitioners were formally employed at the case company and met one or more of the following criteria: (1) They had studied sustainability at the post-graduate level; (2) They had an active role in communicating the results of this study to top management; (3) They were actively involved with sustainability initiatives; (4) They reported on aspects of sustainability (including the carbon disclosure project, corporate social responsibility and integrated reporting) [83,84]. These practitioners represented what Visser and Crane [83] refer to as the sustainability champions and change agents who devote their time and energies to addressing social, environmental and ethical issues within the case company.

The data collection process reinforced the confirmation of emerging themes and the development of robust categories but also served to increase understanding around the phenomena [63,85].

6. Data Analyses

A grounded theory approach to analyzing data supported our goal of constructing theory in a case study design. It enabled us to produce an analytic product in the form of a conceptual framework whilst still maintaining both flexibility and rigor [64].

To build the conceptual framework, we embraced an interpretivist constructivist paradigm [63]. We saw research as developing from interactions between participants and the researchers [74]. We, the researchers, were aware of the influence of our own methodological values, disciplinary perspectives, beliefs and particular philosophical assumptions on the construction of reality and interpretation of knowledge [86]. We tried to instill credibility and objectivity into the design by engaging in reflective sessions and by questioning and challenging emerging findings and thinking, at all times [64,82,86].

For data analysis, we temporarily set the theory aside and focused on familiarizing ourselves with the data [66]. This included readings of the transcribed interviews and the preliminary identification, naming, and mapping of concepts. We followed an open and inductive coding strategy [7,63] which began by describing concepts in terms of their main attributes and assumptions. We then moved to analyzing the data from the focus group interviews. From the evidence in these data sources, patterns, themes, and potential relationships emerged and the exercise continued until no new themes emerged and theoretical saturation was reached [63,82]. We examined rival explanations for the emerging findings, which added value to the development of the relationships between categories [64,74]. In order to explain what was happening, we focused on the underlying dynamics of relationships that emerged from the data [66]. We constantly revisited and compared the data, which served to strengthen the findings and reduce possible biases arising from using a single perspective or data source [63,66]. Initially we had 13 conceptual categories; which included: “Togetherness”; “Power and Position”; and “Single Bottom Line.” Together the researchers engaged in reflective sessions wherein the development and construction of concepts and the interpretation of knowledge was challenged. These sessions served to refine thinking and reduce the number of conceptual categories to seven.

7. Findings and Discussion

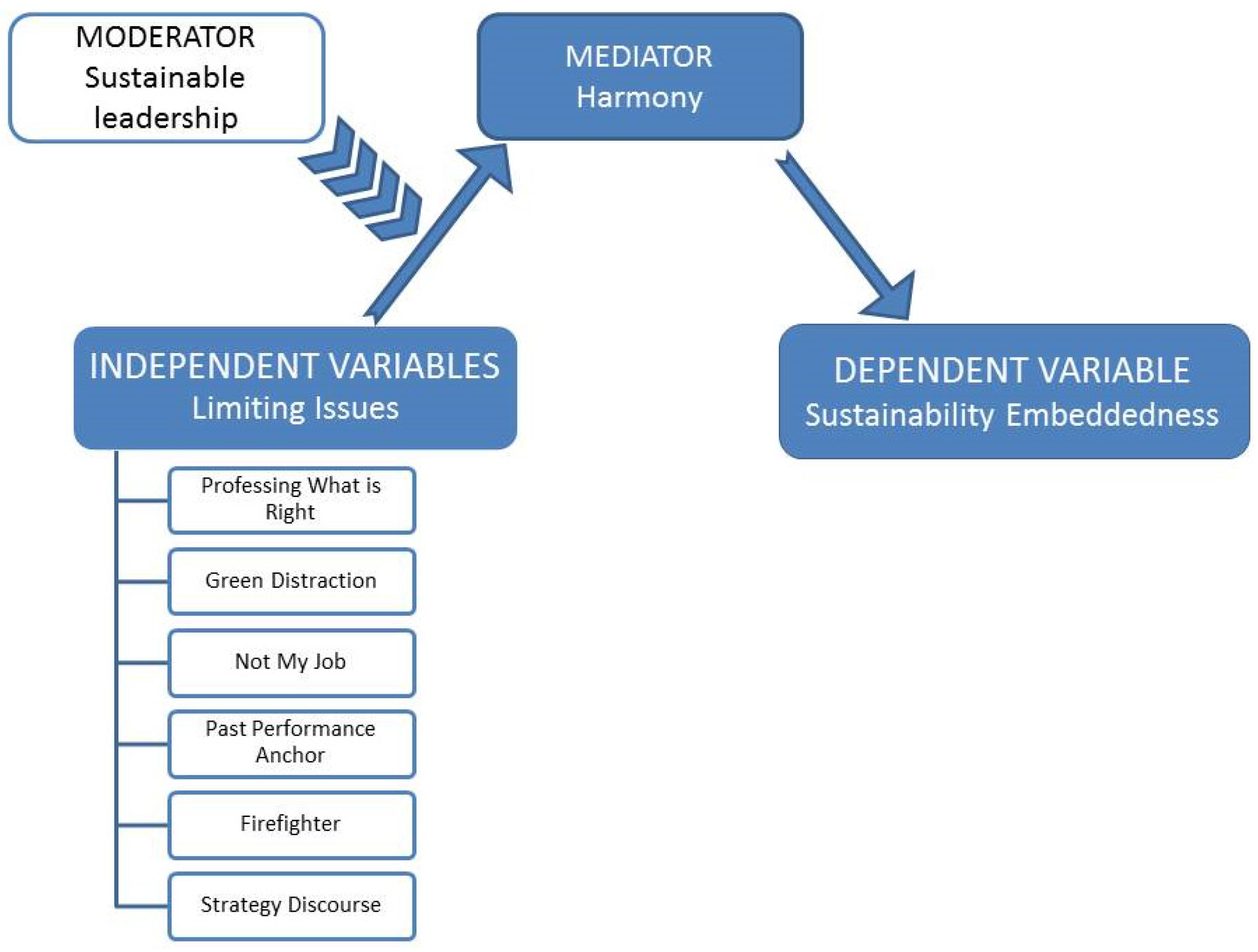

A framework containing the findings of the study and conceptualized limiting issues that inhibit sustainability embeddedness is proposed (Figure 1). The framework rests on the interpreted and constructed perceptions and insights of the researchers after considering the data, engaging in theoretical sampling and participating in extensive conversations. Findings are supported with evidence from direct quotes by participants who formed the basis of our theory-building process. The findings have also been corroborated by related and supporting literature as part of our pursuit of rigor, validity and sharpened construct development [66]. The framework is actually the final result of the process, but it is reported at this early juncture as it portrays the primary findings, their antecedent conditions and proposed relationships. The aim of the framework is to better understand the limiting issues inhibiting sustainability embeddedness and to provide support for management in addressing them, which we believe will lead to improved embeddedness [6,63,86].

Figure 1.

A proposed conceptual framework containing conceptualized limiting issues that inhibit sustainability embeddedness. Source: Own compilation.

7.1. Professing What Is Right

Practitioners in the study, believed without a doubt, that sustainability is “the right thing to do” and that being “sustainable” is an “integral part of how we deliver” and an “important part of business.” This was supported by practitioners who expressed that as a company they always try to be “socially responsible” and had “decided from day one to embrace sustainability.” Practitioners saw sustainability as “non-negotiable” for business, forming part of their strategy. Practitioners knew that sustainability called for “ownership of what is happening in the environment” and that as a company, they should not deplete “everything out of the community.” Instead, they should “respect” and “involve” other stakeholders as “critical role players and offer back where we see opportunities.” Sustainability values and virtues formed a central part of discussions where emphasis was placed on “acting ethically”; “honestly” and “seeking out win-win situations.” Practitioners knew that it was important in their company to conduct business “ethically and fairly” and adhere to “values and ethics” that would support them to “achieve their long-term goals” and “keep delivering results over time.” Sustainability was associated with “complete stakeholder performance” and it was acknowledged that “decisions that you make today that will influence the organization both now and in the future.” Conversely, practitioners shared that “if organizations don’t buy into sustainability” then there would be “negative consequences” that will have an “impact that will be felt down the road in terms of cost and survivability.”

Practitioners confirmed that their company is very committed to “doing the right things” to become a successful business, but we noted that they lacked the transformational belief and thinking that they as a company need to be a successful business in order to continue to “do the right things” (sustainability-embedded orientation) [14,31]. Furthermore, we noted that practitioners prioritized situations in which environmentally friendly and/or socially responsible behavior result in enhanced economic performance, such as their search for “win-win situations” [14,75]. Social and environmental concerns were considered to the extent that they influenced or improved “performance,” “cost” and “results.” Sustainability commitment, corporate behavior and stakeholder engagement focused on—and were limited to—the intersection of the elements of triple bottom line but did not go beyond it [27,48]. Practitioners revealed that their underlying beliefs and attitudes towards sustainability remained economically focused, as opposed to integratively considering all the elements of sustainability. This thinking opposes and inhibits the level of integration associated with sustainability embeddedness [27].

Practitioners professed the importance and a vision of sustainability without hesitation and conveyed strong convictions pertaining to sustainable virtues and values associated with sustainability; however, these professions should rather be considered a limiting issue when they are not accompanied by changes in beliefs and attitudes associated with sustainability embeddedness [15,48]. Professing What Is Right should be interpreted as a False Positive test that could mislead leaders and practitioners to incorrectly believe in the existence of a condition (sustainability embeddedness) when in fact it does not exist. A commitment to sustainability and even strong values proved (and will be demonstrated) to be neither proxies nor precursors for embeddedness and as such, we suggest it be viewed as a limiting issue [47,80,83].

Professing What Is Right is a foundational finding that formed part of our pursuit for construct development and a better understanding of the limiting issues influencing sustainability embeddedness. The finding also confirmed two important features of the study. Firstly, the interpretation of practitioner responses and discourses assured us that the case company operated from a proactive orientation towards sustainability. Secondly, we were able to confirm that participants were aware of the concept of sustainability which enabled them to provide meaningful comments and feedback on the topic of sustainability adoption at their company.

7.2. Green Distraction

“Going green” may sound positive and a green light in the right direction but it should rather be seen as a warning signal to leadership that sustainability is misunderstood and a limitation to embeddedness. Practitioners all supported the idea of sustainability and referred to it as “integral” (Professing What Is Right) but it became clear that there was confusion about its meaning and separateness between the elements of sustainability in the minds of practitioners.

Practitioners appeared to experience two misunderstandings pertaining to sustainability. Firstly, they saw separate “types” of sustainability: a green type and a financial type. One practitioner emphasized this separateness by sharing that there is a “green sustainability” and “financial sustainability.” In general, green sustainability was associated with “green buildings”; “renewable energy”; “green technologies” and “green stuff.” Practitioners expressed that it was “reputationally better to make green decisions” but continued to view financial sustainability as a separate type that was associated with “driving bottom line,” “growth in distribution” and about “sustaining profit.” We also learnt that, according to practitioners, “sustainable green decisions are not necessarily sustainable financially” because they considered the “cost and the absence of a measurable benefit.” Sustainable decisions were said to not always include “green” because “green buildings come at a cost” and that “green isn’t a factor in deal-making or strategic moves.” It appears that practitioners were struggling to integrate different yet equally desirable sustainability elements into their thinking and operations. Secondly, practitioners were confused by the word sustainability and associated it with “anything related to green,” demonstrating that they did not understand it. Sustainability i.e., “greening” according to practitioners, was about “fossil fuels and rhinos,” the “sustainability of the environment” and asking “how can we consume less?” Practitioners associated sustainability with greening initiatives such as the “big energy drive” and saw them as separate to their “corporate finance strategy.”

Two enlightened practitioners could make sense of the issues at hand. One practitioner explained that sustainability embeddedness, and the subsequent making of sustainable decisions, was impeded by “not understanding sustainability in the true sense of the word.” Another practitioner asserted that sustainability is a “misunderstood phrase” and that it should “not only be ‘green’” but that it is “also made up of social, economic and environmental aspects.”

The findings confirmed that practitioners did not really understand the meaning of sustainability nor share similar beliefs about it [17,47]. They perceived the elements of sustainability (social, environmental and financial) separately as opposed to seeing them integratively [20,27]. Separateness not only contrasts the integrative, interconnected and interdependent notions of sustainability but also limits its embeddedness [31,32]. The Green Distraction is proposed as a limiting issue inhibiting embeddedness because as long as practitioners continue to make decisions from this perspective, they will struggle to achieve embeddedness.

7.3. Not My Job

The Not My Job view describes a fundamental belief by practitioners that the management and responsibility for sustainability is somebody else’s (sustainability division) job. We found that practitioners believed that performance in their job, and sustainability were separate ideas with separate responsibilities—which inhibits the transition to sustainability embeddedness [20,43,62].

When discussing sustainability, most practitioners expressed that they “don’t work with things like that” and it “does not resonate in my job.” Furthermore, practitioners shared that there were “no rewards linked to operating in a sustainable way” and that there was “no link between sustainability performance and reward.” Practitioners cited that “some people adhere to sustainability but others don’t” and that “not everyone follows the same protocol.” Practitioners expressed that sustainability decisions were “beyond” their “level of authority,” and we noticed that most practitioners did not mention sustainability as being part of their roles and responsibilities. It became apparent that the practitioners believe that the responsibility for sustainability belongs to the “Sustainability or Utilities department.” Practitioners thought sustainability initiatives to be “excellent” and “encouraging” but, in their view, it is the Sustainability or Utilities department’s responsibility to “change globes” and “deal with the green stuff.” They also referred to an operating structure that is “broken down into silos,” with existent “disconnectedness in departments” which meant that practitioners were “not always aware of sustainability initiatives.”

The shift to embeddedness appears impeded by practitioners not seeing their jobs as interdependent and interconnected with sustainability, which limits embeddedness [20,87]. Practitioners saw the responsibility of sustainability as belonging to those in higher levels of authority (top management) and the tasks belonging to the Sustainability department. Practitioners struggled to connect sustainability to their jobs. This finding is aligned with Hind et al.’s [87] study on the development of leadership competencies that found that practitioners did not perceive sustainability as being part of their responsibility and everyday work, but rather the work of the Chief Executive or the Public Relations (PR) department. The Not My Job belief appears to have been influenced by the existence of a division “tasked” with sustainability [33,35] and was likely reinforced by the existent disconnectedness between departments within the organizational structure, and the absence of rewards aligned with sustainable practices [5,25,45,88]. As long as practitioners hold on to the belief that sustainability is Not My Job, leaders will continue to experience challenges with sustainability embeddedness in their organization.

7.4. Past Performance Anchor

This inhibitor refers to the anchors that keep practitioners focused on performance and practices in the past that serve to impede the shift to embeddedness. The Past Performance Anchor is proposed as a limiting issue that holds practitioners back and fixed to their business-as-usual practices, as opposed to those practices associated with cultural change and innovation for sustainability [31,49,89]. It is known that when practitioners continue along the paths of business-as-usual and profit maximization it renders the destination of sustainability embeddedness impossible to reach [7,9,90].

Practitioners shared that “predicting the future is tricky,” that there was a “fear of new ideas,” and some “reluctance to change.” Practitioners knew that the company had “good historic returns” and performed “exceptionally well in the past.” Even though they had committed to being sustainable, they still believed they could “keep on doing what we’ve been doing” while hoping to “not have a serious impact on the future of the business.” Then, instead of embracing different—i.e. sustainable—operating methods, practitioners indicated that they replicate what they had done in the past by holding onto various anchors. It is as if practitioners asked themselves: “Why change what worked for me in the past?” Practitioner decision-making relied on “past experience” that was aligned with an “existing comfortable fit” and drew on “proven track records”; the “number of successes”; “survey results” and “prior specialist work done.” Practitioners shared that it was important to not make “rash decisions” but rather focus on first getting a “measurable response,” such as with green technology and green building decisions. Practitioners drew heavily on “experience and judgement,” and felt that risk could be avoided by “not taking chances” and by applying “a conservative approach” in business. When daily and strategic decisions were made, such as choosing suppliers or awarding contracts, practitioners relied on “historical knowledge and number of discussions” held; the “number of previous work engagements with them,” and “what worked and what was useful for financials.” Decision-making requirements included “validating” stakeholders’ situations by comparing their current situation to “similar problems in the past.” Sustainability embeddedness appeared further anchored down by what one practitioner described as a “lack of innovation or seeing the big picture.”

Practitioners struggled to make sustainability-embedded decisions because they were being anchored by their fear of the future, their conservativeness, the desire for a comfortable fit, and their usual practice of adhering to what is known and has always been done. Practitioners were also anchored to their business case view which meant that their decision-making for sustainability, such as green buildings, was influenced by their need for a positive financial result, i.e., “what was useful for financials” [27]. It is known that sustainability embeddedness requires real transformational change by management so as to influence practitioners’ daily and strategic decision-making; however, it appears that the necessary change management is inhibited by these anchors [20,76]. As long as practitioners adhere to their business-as-usual patterns held down by these anchors, leaders will struggle to achieve embeddedness. Thus, we suggest that the Past Performance Anchor should be considered a limiting issue influencing the transformational change process required for embeddedness [7,15,17,45].

7.5. Firefighter

Practitioners shared that their daily and strategic decisions and practices were influenced by their need to deal with “problems that occur, for example, Firefighting.” The Firefighter is an in vivo label used to describe practitioners’ responses to their operating context and experienced tensions and pressures, which we suggest is a limiting issue influencing embeddedness.

Even though practitioners understood that “managing sustainability” was about “effectiveness in the long-term,” as well as “considering multiple factors and stakeholders” and “problem solving for long-term solutions,” they instead found themselves Firefighting. Firefighting is their response in the form of “hasty reactions” and “quick action,” to the “opportunities,” “issues,” “demands,” and “requirements” expected of them. Practitioners who saw themselves in a Firefighter position struggled to “manage business requirements and prioritization” and “balance varying priorities and requirements” because they faced “urgent issues” and dealt with “disputes” and “queries” that “popup,” forming part of their “present workload.” Practitioners shared a belief that they were performing in their jobs as long as they did it “on time and efficiently.” Practitioners were also aware that their practices inhibited the making of sustainable decisions and shared that there was a “short-term view currently” and that sustainability was confronted by “short-term thinking that does not consider the future.” When needing to make decisions, practitioners ask themselves: “What is the best solution now?” and believe that “sustainable decision-making is based on current circumstances that present themselves.” The Firefighter inhibitor highlights a short-term view in practitioner understanding of sustainability and explains the internal and external pressures experienced by practitioners by the current operating context. Internal pressures include: “policies and procedures”; the “availability of materials”; “budgets” and “month-end reporting.” External pressures refer to “due diligence”; “legal requirements”; “regulatory issues”; “industry issues” and “year-end reporting.”

Practitioners demonstrated that they are struggling with the inherent tensions (competing alternatives) that form part of sustainability-embedded decision-making [75]. In particular, practitioners struggled with the tension between short- and long-term objectives and between efficiency in their jobs and the resilience of socioeconomic systems. When pressured, it was revealed that practitioners prioritized short-term objectives and efficiency over a long-term and resilient view of sustainability, which limits the transition to embeddedness [48,52]. The Firefighter inhibitor should alert top management to the fact that practitioners are struggling to find synthesis strategies for dealing with sustainability and, at present, are not able to manage the inherent tensions associated with sustainability embeddedness [20,31,48,75]. Firefighting can result in the neglect or dismissal of many important elements of sustainability and is therefore put forward as a limiting issue inhibiting the transitional shift to sustainability embeddedness.

7.6. Strategy Discourse

Based on the earlier findings (Professing What Is Right), there is little doubt that practitioners do in fact know that sustainability is part of their company’s strategy and that the company is committed to its adoption. In spite of this, it strongly emerged that there are challenges with strategy discourse and communication channels that are affecting the organization’s progress to becoming a sustainability-embedded organization.

Strategy Discourse refers to the strategy message and it is put forward as an inhibitor to sustainability embeddedness when it is faulty, or fails to ensure that sustainability “permeates throughout the organization” [20]. Strategy discourse is a tool used by leadership to establish a shared view of the future amongst practitioners pertaining to the organization’s strategy [33,37,47]. Sustainability should be embedded in this strategy message [5,18]. When the strategy message is effectively communicated, then it is one of the most important influencers of culture, practitioner operational behavior, and corporate performance in terms of sustainability [10,15]. This is because practitioners make decisions based on strategy—which needs to be clearly heard [91]. In general, practitioners in this study (from all functions, divisions and geographic locations and management levels) revealed that the strategy message is not clearly conveyed or disseminated.

Practitioners pointed to the Strategy Discourse inhibitor when they shared that, currently, the “strategy is not known to everyone,” that they do not have “a lot of exposure” to strategy and that there are “not enough discussions around strategy.” Many practitioners referred to the company’s strategy as “vague”; “unknown to me”; “unclear”; “secret”; or “not shared,” and voiced that leaders were “lacking in engagement” with them and needed “better communication with staff.” Practitioners struggled to “conceptualize strategy” for themselves and in their jobs, and believed that strategy messages were “not being communicated.” Practitioners attributed their experienced challenges to “poor communication outside of top management,” and information “not filtering down” to them, and messages “not being communicated all the way down.” One practitioner confirmed this view by expressing that it was not possible to comment on strategy because it belonged to “executive management or top management,” clearly indicating that there were challenges in the filtered communication of the strategy message. One practitioner provided an analogy to feeling left “in the dark.” If this is true for strategy in general, then leaders should be even more concerned about the status of the sustainability message.

Practitioners confirmed the need for concern when they shared the view that there was “limited communication around sustainability.” Practitioners felt they were “not always aware of sustainability initiatives” and that they were “only partial to some information” on sustainability. Practitioners reported that sustainable practices and embeddedness might be impeded by “not having clear vision from leaders on sustainability.” This resulted in practitioners experiencing gaps in their understanding about where they are in terms of sustainability adoption and where they need to be.

Numerous authors have reiterated that, in order to successfully integrate sustainability, leaders need to convey the strategy message of sustainability in such a way that it is relevant to—and heard by—all the members in the organization [1,6,10,47,92]. However, it appears that the current methods and means of strategy discourse and communication are not adequate to effectively change attitudes, beliefs and behaviors about sustainability, towards a sustainability-embedded orientation [20,46,52,62]. The current methods of discourse may have established a shared knowledge amongst members that the company is committed to integrating sustainability, but nonetheless failed to improve practitioners’ understanding of the concept (Green Distraction); or help them see the connection between sustainability and their jobs (Not my Job); or to convey how practitioners should manage sustainability (Firefighter). Strategy Discourse should ignite the necessary changes in order to achieve the desired sustainability-embeddedness outcome, and when failing to do so, we suggest it be considered an inhibitor to embeddedness [46,52,62,93,94].

7.7. Harmony and Sustainable Leadership

Harmony was found to be a very important influence on the shift to sustainability embeddedness. Harmony may have other names in the literature, such as organizational alignment or congruence, and it may not be a novel idea, but its impact and importance for embeddedness is reiterated here and should not be underestimated by those in practice. Harmony emerged from engagements with practitioners and the interpretation of the other inhibitors. It was then confirmed by literature on the topic of sustainability embeddedness [15,20]. In the context of sustainability embeddedness and this study, a harmonious state is achieved when sustainability has permeated throughout the organization so that there is unity amongst corporate and practitioner beliefs, decision-making and practices, and interconnectedness between economic, social and environmental goals and strategizing. One practitioner shared a metaphor that helped us better understand Harmony. The practitioner shared that sustainability embeddedness was only possible when “the entire team is singing off the same hymn sheet”—highlighting the need for complete agreement, unity and connectedness for sustainability embeddedness in practice.

Practitioners alluded to Harmony as being the “connection and alignment amongst people’s thoughts and decisions” believing that it would “strengthen one another.” Practitioners articulated a need for “co-congruence” and “togetherness” in practice and for Harmony-like, “collaborative” behavior centered on “working together”—suggesting that it could positively influence sustainability embeddedness. Harmony’s relationship to the limiting issues emerged as a mediator to either achievement or non-achievement of the transition to sustainability embeddedness. A mediator through which all the inhibitors operate as if it is a dimmer switch through which electric current is regulated. When Harmony is absent or impaired, the limiting issues will continue to inhibit embeddedness. However, when Harmony is addressed, then it supports management to achieve embeddedness. Practitioners described their experience by saying that there is presently an “uncoordinated and disconnected approach” that was referred to as a challenge to making sustainability-embedded decisions. It became clear that the transition to sustainability embeddedness was being restricted by practitioners not “thinking along the same ideas,” and existent “differences” in understanding and in their practices. Conversely, it is known that when organizations do think and work collaboratively (harmoniously) towards a broader set of sustainability objectives, they are often considered to be embedded with sustainability [20,41,62].

A harmonious state (interconnectedness) came forward as strongly moderated by sustainable leadership (Figure 1). Sustainable leadership (the moderator), in this context, is seen to alter the impact of the limiting issues (independent variables) and the mediating role of Harmony on sustainability embeddedness (dependent variable). The objective of sustainable leadership is aligned with that of Harmony, which is to keep people, profits, and the planet in balance over the life of the organization. The findings suggest that the absence of Harmony and the existence of limiting issues may actually be a strong impetus for increased attention to sustainable leadership [1]. Practitioners suggested that they needed a type of leader that would take charge of championing a “coherent strategy that integrates the different parts of business.” Practitioners articulated the need for a leader tasked as a “driver of the operations of the business” who would also initiate “debates and discussions on the triple bottom line” and “integrate the culture,” thereby assisting everyone to “have the same goal” so as to shift to embeddedness. Practitioners saw this type of leader as a transformer that could support them to overcome the various inhibitors affecting sustainability embeddedness [15]. The literature supports this finding and describes the establishment of an enabling, shared culture for sustainability as a foundational sustainable leadership practice that is connected to sustainability embeddedness [10,17,33]. Leaders also play an important role in establishing the congruence between employees’ concerns (on all management levels) and organizational values and, towards organizational commitment to sustainability [1,17,83,89,92].

In this section we presented the conceptualized findings influencing sustainability embeddedness, which emerged from the experiences of practitioners in the social realities of their everyday organizational life. The findings were confirmed and discussed using a theory established from a wide literature search. As part the presentation of the findings, we proposed relationships and explained how the findings influence embeddedness. In this next section, we provide evidence and support for the conceptual framework after returning to the case company for further theoretical substantiation.

8. Support for the Credibility of the Conceptual Framework

We presented the conceptual framework (Figure 1) to a group of sustainability practitioners at the company who were chosen by means of theoretical sampling for their interest and association with sustainability. The opinion of these sustainability practitioners is particularly relevant in confirming the findings because sustainability is central to their jobs [84].

After verbally explaining and graphically displaying the findings and facilitating a focused discussion, practitioners supported all the limiting issues as being a true reflection of the inhibitors to sustainability embeddedness at their organization. Sustainability practitioners’ average agreement for all the findings ranged from 3 to 4.25 using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Low and 5 = High). Practitioners strongly agreed (average rating of 4) with the Firefighter inhibitor because they could relate to existent short-termism and the pressure experienced by practitioners when making sustainability-embedded decisions. Practitioners also strongly agreed and confirmed the Not My Job view as a limiting issue, by giving it an average rating of 4. Sustainability practitioners could all relate to the issue of other practitioners not seeing sustainability as being part of a shared responsibility. These practitioners strongly supported the Green Distraction issue, knowing that sustainability was misunderstood by those in practice, and elements of sustainability were commonly considered separately, as opposed to integratively, which limits embeddedness. They gave the Green Distraction an average rating of 4.25. The practitioners in this group reiterated the need for continuous efforts of engagement with divisions as well as across management levels, with the purpose of enhancing knowledge and understanding around the phenomenon.

In the next section we discuss the implications of the findings for leaders, management and change agents. The aim is to guide and support them to respond to the inhibitors by incorporating them as part of the transformational change process towards embeddedness.

9. Sustainable Leadership and Management Implications

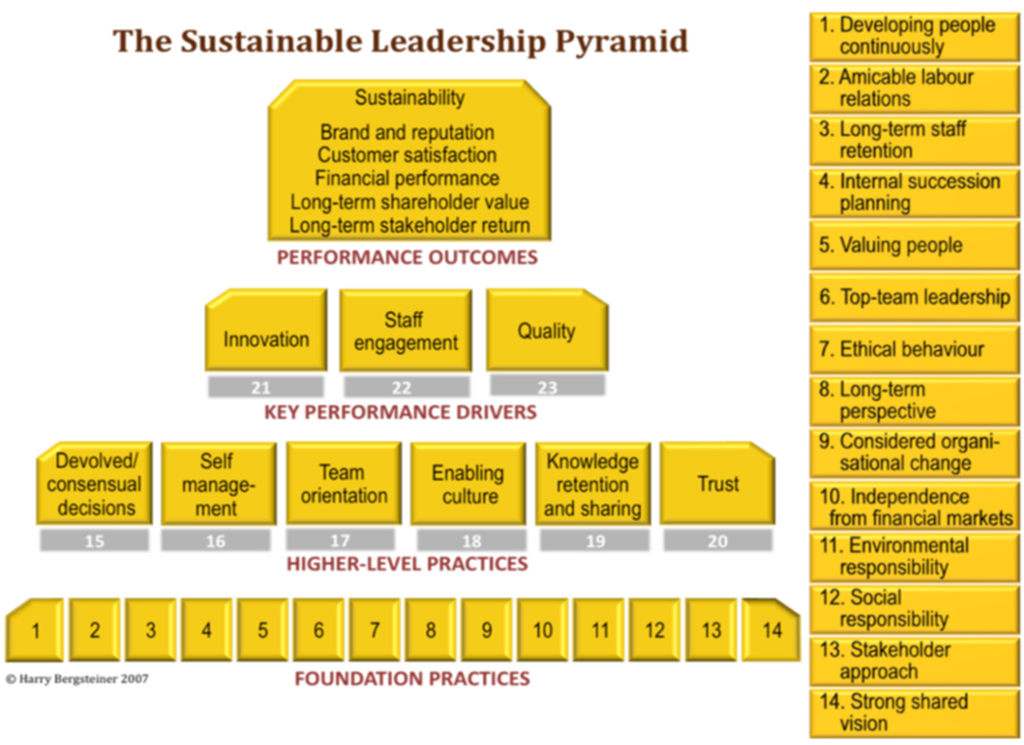

Cultural change is not an easy task [73] and there is a growing awareness that the success or failure of sustainability embeddedness is dependent on leadership’s ability to “manage humans and culture,” as opposed to applying and facilitating technical systems and tools [95]. The findings emphasized the important moderating role of sustainable leadership in the embeddedness process, the creation of a harmonious state and the overcoming of the inhibitors. In this section we will discuss the specific sustainable leadership practices that can support leaders in overcoming the limiting issues inhibiting embeddedness, so as to transition to embeddedness. To do this, we draw on Avery and Bergsteiners’ [10,44] 23 “honeybee” sustainable leadership practices as a foundation for our discussion and recommendations. These are contained in Appendix and reference has been made to these practices in our discussion.

The Professing What Is Right inhibitor demonstrated that leaders in the case company have already instilled the importance of ethical behavior (7) and a strong commitment amongst practitioners to protect the environment (11), value people and the community (12) and to include all groups of stakeholders (13). Even though practitioners promoted sustainability as the “right thing to do” it was found to not be a precursor to embeddedness, but was in fact a distraction. Practitioners still require a paradigm shift in their individual beliefs and understanding towards embeddedness as part of their core values (7). Leaders and managers should pay attention to the transformational change requirements (9) associated with a shift to embeddedness and the overcoming of the inhibitors, and not allow themselves to be distracted by the very positive statements and commitments towards sustainability made by practitioners.

The Green Distraction inhibitor confirmed that practitioners knew that it was important to protect the environment (11) and “go green” but demonstrated a lack of understanding about what sustainability means as a principal belief and value (7). Practitioners did not fully comprehend sustainability and saw the elements of sustainability separately, as opposed to integratively, for example, seeing Greening as separate from the “corporate finance strategy.” Practitioner dialogue demonstrated that the underlying objective remains economic, which indicated a business case or shareholder-first philosophy approach to business that is the opposite of a sustainable “honeybee” philosophy [10,27]. Sustainable leaders understand the importance and interconnectedness between people, planet, and profit, but need to instill this belief amongst individual practitioners on all levels to achieve embeddedness. Leaders desiring to address this inhibitor and influence practitioner beliefs about sustainability embeddedness should start by refocusing their organizational change efforts (9) by reframing issues and focusing on embedding an integrative and inclusive view of sustainability [10,17,84]. To do this, leaders need to become active team members (6), collaborate with practitioners in their operating context, and use effective strategy discourse to promote the attributes of organizational, social and environmental resilience, as opposed to profit [27,83,84]. Leaders could draw practitioners’ attention to the urgent need for business to prioritize resource use and make daily strategic decisions that include communities [40,84]. These efforts should help practitioners develop a personal understanding of sustainability, as well as integrate it into their beliefs and attitudes. It is also important that leaders focus on the establishment of continuous knowledge sharing (19) networks so that sustainability spreads throughout the organization and forms part of a shared and embedded culture for sustainability (18) [10].

The Not My Job view demonstrated that practitioners did not see sustainability as part of their jobs and that they believed that sustainability was the responsibility of the sustainability department. Leaders addressing this inhibitor need to better integrate the sustainability department into the organizational structure so that it does not remain a peripheral “disconnected” department [10,25,26,35]. This is because inter-organizational interdependence is considered instrumental in embedding sustainability [20]. Leaders should start by engaging with staff members to develop cooperation and collaboration networks towards the broader goal of sustainability (2) [10,84]. It is important that leaders involve practitioners as team members in sustainability initiatives (17) and incorporate sustainability into practitioners’ jobs and evaluation systems [20,35,41,62]. This will help practitioners to see sustainability as part of their jobs and could even result in innovations and new projects for sustainability (21) [19]. It is also important that decision-making within the current structure is decentralized and consensual (15) and not restricted to top management, or the sustainability department. Practitioners should feel that they are part of the implementation of sustainability and be made to believe that sustainability-embedded decisions are not beyond their level of authority [10,87].

The Past Performance Anchor directly emphasized challenges with organizational change (9) associated with the transition to an embedded orientation. Practitioners appear to be holding onto their “default” ways of doing things which we identified as anchors to the past, rooted in their beliefs, economic goals, comfort and fears. It is suggested that leaders and managers incorporate the identified Past Performance Anchors into the change management process as a means to overcome the limiting issue. Part of what was found to be keeping practitioners adhering to their business-as-usual modus operandi, was the fact that they experienced a “lack of innovation or seeing the big picture.” In response to this inhibitor, we recommend that leaders start by establishing a shared view (vision) of the future (14) because the absence of clarity around sustainability can also be used as an excuse for the continuation of a business-as-usual approach [23]. Leaders could help practitioners “see the big picture” and advance towards the vision of sustainability embeddedness through strategy discourse, engagement and written communication. Leaders should also aim to develop innovative practices (21) and demonstrate the various opportunities associated with sustainability [10,18,84,96]. Innovation for sustainability could be developed through finding creative ways to address sustainability concerns whilst still aiming to perform well as an organization [10,18].

The Firefighter inhibitor highlighted that practitioners are struggling with the management of sustainability in their operating context and with the tensions found in daily and strategic decision-making. It emerged that practitioners prioritize short-term objectives (8) and believe that they are doing their job if they do it on time and efficiently. Granted that all companies still need to survive financially in the short term, a short-term perspective to business—as opposed to a long-term perspective—can lead to non-sustainable practices and diminished resilience [10,27]. The Firefighter inhibitor emphasizes the importance of leaders establishing a long-term perspective (8) for practitioners, and also the importance of guiding them to make synthesis-focused—i.e. sustainability-embedded—decisions. For instance, managers should make sure that practitioners are forgiven and not punished for not meeting short-term financial objectives when they have made a sustainability-embedded choice [48]. It is also important that practitioners have adequate capacity and resources to make sustainable decisions [27,56]. Managers and leaders should evaluate practitioners’ operating context and workloads that were found to be affecting their decision-making. It is necessary that they review and respond to the internal and external pressures experienced by practitioners, such as reporting requirements, deadlines and current policies that may be promoting short-termism and do not yet embody the principles of an inclusive and holistic view of sustainability [17,34,42,97,98]. Practitioners will be better able to make or prioritize long-term and resilient decisions when their performance evaluations, incentives and remuneration are aligned [5,10,45,47,88].

The Strategy Discourse inhibitor pointed to faltering communication and the unsuccessful transfer of a deep-seated sustainability message to practitioners. The knowledge and sharing of sustainability appeared to have not been spread effectively across the organization (19). Ineffective communication channels by leadership result in mixed messages and confusion often impacting the creation of a sustainability-embedded organizational culture (18) and ultimately the desired performance outcome (embeddedness) [47,61,99]. Practitioners found the current strategy message to be “vague” and “unclear” and called for more discussions around sustainability as well as debates on the triple bottom line. Practitioners also felt that important strategy and sustainability messages were “not filtered down.” To address this inhibitor, leaders should focus on becoming a top team speaker (6), or a champion for sustainability where the vision and purpose of sustainability is shared (14) [10,27,52,83]. It is important that leadership build cooperation amongst staff (2) through team building (17) towards sustainability, in order to become a sustainable organization [62,95]. Top management should look to engage middle managers in conveying the strategy message of sustainability throughout the organization. Middle managers are considered crucial role players in sustainability embeddedness and are able to enhance discourse through actions such as translating, mediating, negotiating and monitoring of the strategy message [10,46,62,76,77].

Ackerman [100] states that, “…if a recurring pattern can be identified and analyzed, it can also be consciously managed.” Each of the findings has significant implications for organizations and needs to be consciously managed. In this section, the findings have been discussed and suggestions have been made pertaining to strategic and operational responses that could contribute to enhanced embeddedness.

10. Contribution and Concluding Thoughts

In addition to leaders in this case company, other leaders from various contexts are likely asking: “Why are we not progressing towards sustainability embeddedness? What is limiting us from becoming a sustainable organization?” Although one should resist the temptation to draw general conclusions from a single case design, we believe that the proposed conceptual framework (Figure 1) and the sustainable leadership recommendations offer valuable insight and support to managers and academics in answering this question and at the same time make a unique contribution to the literature. The framework serves the important role of directing the actions of sustainable leaders by helping them to focus and prioritize the limiting issues in their pursuit for embeddedness. Whilst we accept that the paths of how firms embed sustainability are not generic—even within organizations, industries or countries—we believe that managers from various contexts can resonate with the conceptualized limiting issues and insights presented in this paper, and that they are potentially transferable to other contexts.

Our study explored the transitional space between proactivity and embeddedness in terms of sustainability adoption, and offers a better understanding around the limiting issues that contribute to the existent implementation gap between desired and actual embeddedness. Even though sustainability embeddedness is not a new concept and is a legitimate orientation for business, the theory around how to distinguish between the orientations has only recently been clarified and there are limited practical studies that have explored this gap between the orientations [20,27].

We found immense value came from our methodological choices, which forms part of our overall contribution. We focused on real-life situations and the tangible struggles of a diverse group of practitioners and allowed the findings to emerge from the data in a case study context [66,101]. We interpreted the data holistically. This meant that we considered all the limiting issues inhibiting embeddedness, which included a combination of beliefs and operational challenges. As part of our grounded theory approach, we constantly compared the findings to each other, so as to better understand the relationships between them and to construct a picture of the social reality. Through this rigorous process we have been able to propose a unique conceptual framework of limiting issues that represents a collated source of inhibitors and their antecedent conditions in a manner that has not been proposed before (Figure 1). The inhibitors limiting sustainability embeddedness are: Professing What Is Right; Green Distraction; Not My Job; Past Performance Anchor; Firefighter; and Strategy Discourse. These were found to be mediated by Harmony—the interconnectedness required for embeddedness. All these were also found to be moderated by Sustainable leadership.

Throughout this study, we maintained a dual purpose of conceptualizing the limiting issues by building theory empirically through the contribution of a conceptual framework, and testing theory by going back to literature with our findings. We synthesized and reviewed a wide scope of related literature, frameworks and theories related to embeddedness, including; sustainable leadership; organizational change and culture; decision-making; sustainability adoption; and theory developed from case studies. After doing this, we returned to our findings to challenge and confirm what we had found using the literature. We also aimed to “raise the theoretical level” of our own findings in this process and add depth and further understanding to our interpretations [66]. We determined that our findings offered new insight, relationships, and evidence, even though similar and related findings have been discussed in various studies in the past. Our findings offer unique labels, antecedent conditions and provide illustrated examples of the tangible struggles experienced by practitioners that contribute to a better understanding of the limiting issues inhibiting embeddedness. We determined that previous studies have contributed to the phenomena in isolation and unlike this study, they did not focus specifically on the limiting issues or conceptualize them in a framework, nor did they intend to.

Notwithstanding the benefits of the chosen research design and our study’s contribution, this study has its limitations which should be considered when interpreting the results. At the outset of our research, there was no framework. During the collection of data (reading and rereading of data) several frameworks were developed which were repeatedly adapted to account for new insights. Consequently, the final proposed framework is the interactive conceptualization of the researchers, who are by nature subject to their own biases as well as experiences [63]. The proposed framework tends to categorize related and unrelated issues into “boxes” in order to improve understanding through analysis. Using such a framework obviously has limitations but we believe that its advantages outweigh these limitations. Future research could more deeply explore (individually or collectively) the limiting issues and findings in other contexts. Future studies could also explore the moderating and mediating relationships between the limiting issues and sustainability embeddedness which were proposed in this study. Future studies could also further develop or test the findings by gathering additional data and theory substantiation.

There is no question about sustainability presenting an interesting and challenging topic for research. We found that sustainability remained a complex phenomenon and the findings of the study confirm this. There are competing, overlapping, intertwined issues that require management’s attention. We hope that this paper will offer managers and leaders points of departure for conversations on the topic and stimulate academic discussion around sustainability embeddedness, both locally and internationally. It is, after all, time that business changes from patterns of business-as-usual, to business as unusual [81].

Acknowledgments

The case company for permitting this research and for striving to embed sustainability.

Author Contributions

Both authors designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the paper together.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Figure A1.

The Sustainable Leadership Pyramid containing 23 Honeybee practices for Sustainable Leaders. Source: Avery and Bergsteiner [10].

Figure A1.

The Sustainable Leadership Pyramid containing 23 Honeybee practices for Sustainable Leaders. Source: Avery and Bergsteiner [10].

References

- Avery, G.; Bergsteiner, H. How BMW Successfully Practices Sustainable Leadership Principles. Strategy Leadersh. 2011, 39, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiron, D.; Kruschwitz, N.; Haanaes, K.; Reeves, M.; Von Streng Velken, I. Sustainability Nears a Tipping Point. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doane, D.; MacGillivray, A. Economic Sustainability: The business of staying in business. New Econ. Found. 2001, 1, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hallstedt, S.; Ny, H.; Rovert, K.; Broman, G. An approach to assessing sustainability integration in strategic decision systems for product development. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.; Fisher, J.G.; Stuart, N.V. Integrating Sustainability with Corporate Strategy: A Maturity Model for the Finance. J. Corp. Account. Finance 2012, 23, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, P.; Chitty, N. Meaning Making by Managers: Corporate Discourse on Environment and Sustainability in India. J. Bus. Ethics. 2014, 123, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, T.; Huge, J.; Verbruggen, A.; Wright, T. Sustainable Development: A Bird’s Eye View. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1637–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perey, R. Making sense of sustainability through an individual interview narrative. Cult. Organ. 2015, 21, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrott, B. The sustainable organisation: Blueprint for an integrated model. J. Bus. Strategy 2015, 35, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable Leadership Practices for Enhancing Business Resilience and Performance. Strategy Leadersh. 2011, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.K.; Slater, S. Hitting the Sustainability Sweet Spot: Having it All. J. Bus. Strategy 2010, 1, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future; Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; World Commission on Environment and Development: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Hill, G.; Pfitzer, M.; Patscheke, S.; Hawkins, E. Measuring Shared Value: How to Unlock Value by Linking Social and Business Results. Available online: http://www.fsg.org/publications/measuring-shared-value (accessed on 14 November 2015).

- Dyllick, T.; Muff, K. Clarifying the Meaning of Sustainable Business: Introducing a Typology from Business-as-Usual to True Business Sustainability. Organ Environ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A. Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Wagner, M. Integrating Sustainability into Firms’ Processes: Performance Effects and the Moderating Role of Business Models and Innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C.; Crane, A. The Greening of Organizational Culture: Management Views on the Depth, Degree and Diffusion of Change. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2001, 15, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, S.J.; Hope, C. Incorporating sustainable business practices into company strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillestad, T.; Xie, C.; Haugland, S.A. Innovative corporate social responsibility; the founder’s role in creating trustworthy corporate brand through “green innovation”. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 440–451. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, M. Theorizing Firm Adoption of Sustaincentrism. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, B. The 5-Stage Sustainability Journey. Sustainability Advantage. Available online: http://sustainabilityadvantage.com/2010/07/27/the-5-stage-sustainability-journey/ (accessed on 14 March 2016).

- Benn, S.; Dunphy, D.; Griffiths, A. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]