World Heritage Site Designation Impacts on a Historic Village: A Case Study on Residents’ Perceptions of Hahoe Village (Korea)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Community Sustainability of Historic Villages

1.2. Residents’ Perceptions

2. Materials and Methods

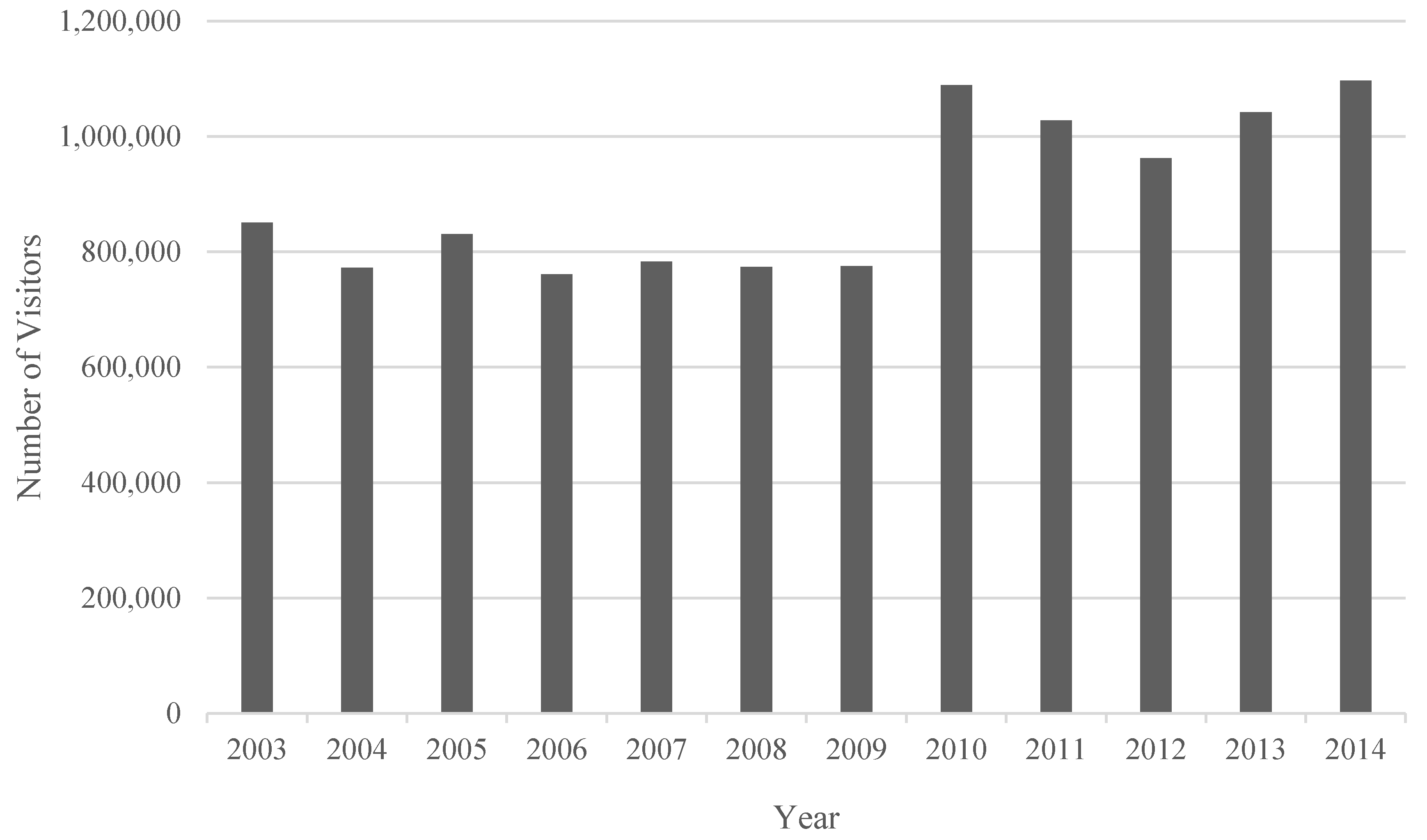

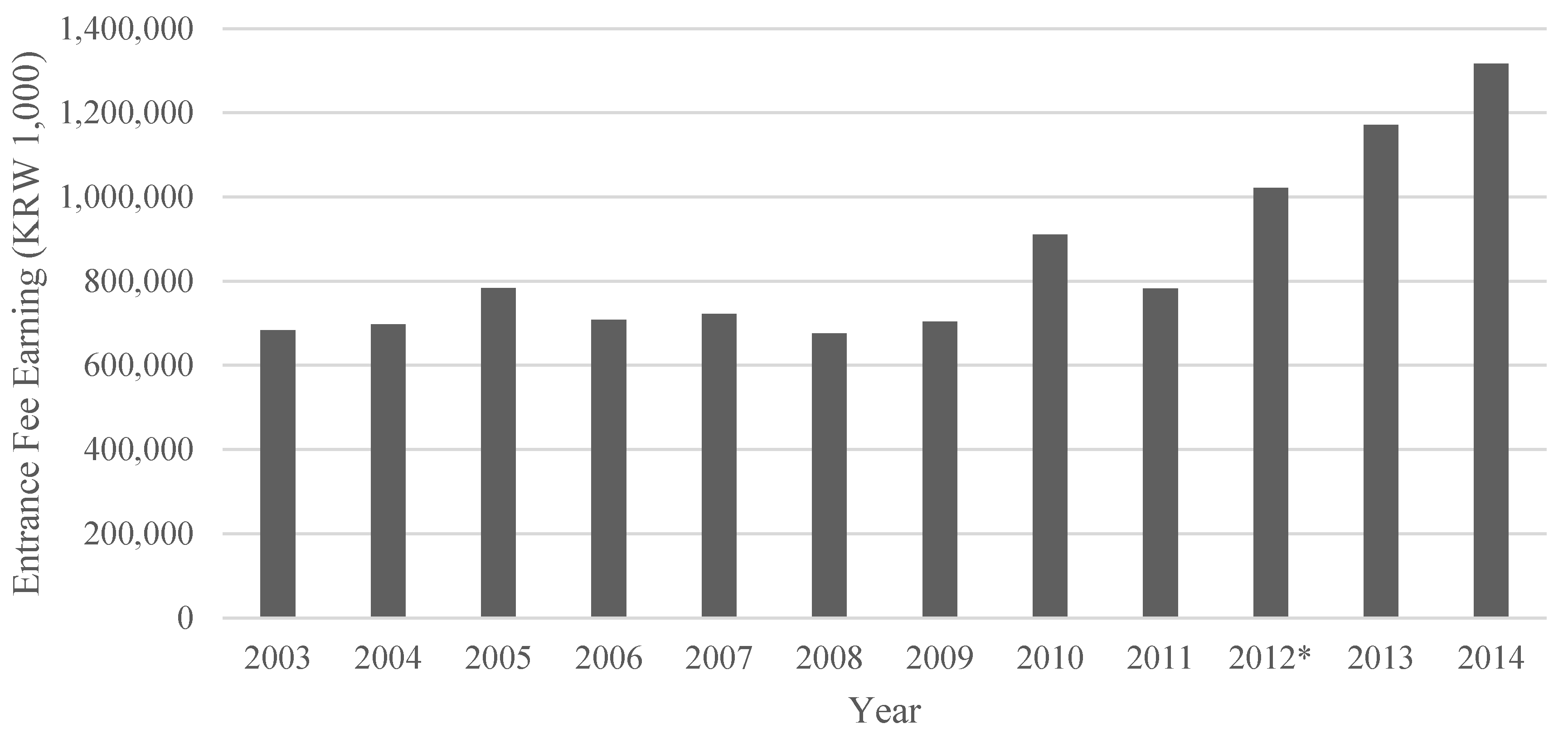

2.1. A Case Study: Hahoe Village

2.2. Study Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Acceleration of the Change of the Industrial Base of Hahoe Village and the Influx of Non-Locals

The term Maul originated from “Moul” or “Modul” which means an assembly. People lived together, and formed a group. As a group, they had mutual cooperation. They called their place for this mutual cooperation a Maul. In Korean society, this image of mutual cooperation was reflected everywhere in the Maul, and the place of Maul provided the living space for settlers. However, most Mauls changed and disbanded rapidly during modernization. In this process, the Mauls lost their original form and spirit.(p. 19)

4.2. The Degradation of the Quality of Life (in the Physical Aspects) Based on Increasing Tourism

4.2.1. Impacts of Increasing Tourism on Residents’ Quality of Life

4.2.2. WHS Designation and Satisfaction with Quality of Life

4.3. The Collision Predicated by the Tension between Conserving the Historic Environments and Developing Tourism

Designation of a WHS implies change, increased visitor numbers, more traders, [and] governments seeking to enhance the site by over-restoration and damage to landscape by intrusive development such as landscaping or mineral extraction. Large visitor numbers create problems; crowding can lead to frustration and thus to vandalism. There need to be mechanisms for clearing litter, repairing paths, and considering site ecology as well as the welfare of visitors.(pp. 7–8)

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HVPS | Hahoe Village Preservation Society |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| WHC | World Heritage Convention |

| WHL | World Heritage List |

| WHS | World Heritage Site |

References

- Shackely, M. Introduction—World Cultural Heritage Sites. In Visitor Management: Case Studies from World Heritage Sites, 1st ed.; Shackley, M., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Poria, Y.; Reichel, A.; Cohen, R. World Heritage Site: Is it an effective brand name? A case study of a religious heritage sites. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A.; Rakic, T. The future market for World Heritage Sites. In Managing World Heritage Sites, 1st ed.; Leask, A., Fyall, A., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic, T. World Heritage: Issues and debates. Tourism 2007, 55, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Shackley, M. Visitor management at World Heritage Sites. In Managing World Heritage Sites, 1st ed.; Leask, A., Fyall, A., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wu, B.; Cai, L. Tourism development of World Heritage Sites in China: A geographic perspective. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F. Foreword. In The Politics of World Heritage: Negotiating Tourism and Conservation, 1st ed.; Harrison, D., Hitchcook, M., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2007; pp. v–vi. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, L.N. Stakeholder Perspectives on the Pitons Management Area in St. Lucia: Potential for Sustainable Tourism Development. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lew, A.A.; Ng, P.T.; Ni, C.; Wu, T. Community sustainability and resilience: Similarities, differences and indicators. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, P.; Beccaro, G.L.; Larcher, F. Assessing and monitoring the sustainability in rural World Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14186–14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P. Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, C. A framework for sustainable heritage management: A case study in UK industrial heritage sites. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietala-Koivu, R. Agricultural landscape change: A case study in Yläne, southwest Finland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 46, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Sustainable landscapes: Contradiction, fiction or utopia? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.H. Reading the Korean Cultural Landscape, 1st ed.; Hollym: Elizabeth, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 176–221. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J. Host community acceptance of foreign tourists: Strategic considerations. Ann. Tour. Res. 1980, 7, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.R.; Long, P.T.; Perdue, R.R.; Kieselbach, S. The impact of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. J. Travel Res. 1988, 27, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.; Vogt, C. The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Vogt, C.A.; Knopf, R.C. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. A cross-cultural analysis of tourism and quality of life perceptions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions research on the social impacts of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brougham, J.; Butler, R. A segmentation analysis of resident attitudes to the social impact of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Assessing and visualizing tourism impacts from urban residents’ perspectives. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2001, 25, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, P.C. Resident attitude toward heritage tourism development. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Murray, I. Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H. Forms of adjustment: Sociocultural impacts of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1989, 16, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterling, D. Residents and tourism: What is really at stake? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2005, 18, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, M.P. Heritage, local communities, and economic development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralambopoulos, N.; Pizam, A. Perceived impacts of tourism: The case of Samos. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimura, T. The impact of World Heritage site designation on local communities: A case study of Ogimachi. Shirakawa-Mura, Japan. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khizindar, T. Effects of tourism on residents’ quality of life in Saudi Arabia: An empirical study. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 617–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Pizam, A.; Milman, A. Social impacts of tourism: Host perceptions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1993, 20, 650–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.W.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Var, T. Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Ann. Tour. Res. 1986, 13, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sheldon, P.J.; Var, T. Resident perception of the environmental impacts of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L. An Exploratory Investigation of Perceived Tourism Impacts on Resident Quality of Life and Support for Tourism in Cologne, Germany. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.; Long, P.; Allen, L. Resident support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Advisory Body Evaluation: Hahoe and Yangdong (Republic of Korea) No. 1324. 2010. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/1324.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2016).

- Buckley, R. The effects of World Heritage listing on tourism to Australian national parks. J. Sustain. Tour. 2004, 12, 70–84. [Google Scholar]

- Shackley, M. (Ed.) Visitor Management: Case Studies from World Heritage Sites, 1st ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1998.

- Shieldhouse, R.G. A Jagged Path: Tourism, Planning, and Development in Mexican World Heritage Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Andong Hahoe Village. (In Korean)Available online: http://www.andong.go.kr/hahoe/main.do (accessed on 29 January 2016).

- UNESCO World Heritage Center. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/ (accessed on 29 January 2016).

- Kim, S.S.; Wong, K.K.F.; Cho, M. Assessing the economic value of a World Heritage Site and willingnees-to-pay determinants: A case of Changdeok Palace. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Preservation and Utilization of Folk Village and Planning for Detailed Comprehensive Management; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Keitumetse, S.O. Cultural resources as sustainability enables: Towards a community-based cultural heritage resources management (Cobachrem) model. Sustainability 2014, 6, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Henderson, J.C. Sustainable rural tourism in Iran: A perspective from Hawraman Village. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 2–3, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.W. In Quest of Traditional Villages of Korea, 1st ed.; Humanist: Seoul, Korea, 2011; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirgy, J.; Rahtz, D.; Cicic, M.; Underwood, R. A method for assessing residents’ satisfaction with community-based services: A quality of life perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2000, 49, 279–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, M.R.; Cummins, R.A.; Ferriss, A.L.; Land, K.; Michalos, A.C.; Peterson, M.; Sharpe, A.; Sirgy, J.; Vogel, J. Quality of life indexes for national policy: Review and agenda for research. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 55, 1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. Tourist impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. J. Travel Res. 1978, 16, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F.; Martin, S.R. Community attachment and attitudes toward tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1994, 32, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppel, H.; Hall, C.M. Selling art and history: Cultural heritage and tourism. J. Tour. Stud. 1991, 2, 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rössler, M. World Heritage cultural landscapes: A UNESCO flagship programme 1992–2006. Landsc. Res. 2007, 31, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. Living in a World Heritage city: Stakeholders in the dialectic of the universal and particular. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 8, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbasli, A. Tourists in Historic Towns: Urban Conservation and Heritage Management, 1st ed.; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shackely, M. Conclusions—Visitor management at cultural World Heritage Sites. In Visitor Management: Case Studies from World Heritage Sites, 1st ed.; Shackley, M., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Center. Information Document Glossary of World Heritage Terms 1996. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/gloss96.htm (accessed on 29 January 2016).

- UNESCO Culture Sector. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/?pg=00103 (accessed on 29 January 2016).

- Keitumetse, S.; Nthoi, O. Investigating the impact of World Heritage site tourism on the intangible heritage of a community: Tsodilo Hills World Heritage site, Botswana. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2009, 4, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Munjeri, D. Tangible and intangible heritage: From difference to convergence. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J. The Economic Value of Hahoe Traditional Village As a World Cultural Heritage and the Way of Preservation: A Case Study of Shirakawa-Mura, Japan. Ph.D. Dissertation, Kyonggi University, Suwon, Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser, N. Planning for urban heritage places: Reconciling conservation, tourism, and sustainable development. J. Plan. Lit. 2003, 17, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Funds for Cultural Heritage Restoration (KRW) | Funds for Tourists’ Facilities (KRW) | Funds for the Rest (KRW) | Total Funds for Hahoe Village (KRW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10,813,000,000 | 10,863,000,000 | 5,550,000,000 | 27,226,000,000 |

| Demographic Characteristics (n = 42) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 28 | 66.7 |

| Female | 14 | 33.3 | |

| Age | 30–39 | 2 | 4.8 |

| 40–49 | 8 | 19.0 | |

| 50–59 | 12 | 28.6 | |

| 60 and over | 20 | 47.6 | |

| Highest level of education | High school or less | 20 | 47.6 |

| College/university | 18 | 42.9 | |

| Graduate school | 4 | 9.5 | |

| Participation in tourism industry | Participation | 26 | 61.9 |

| Nonparticipation | 12 | 28.6 | |

| Nonresponse | 4 | 9.5 | |

| Impact Variables * | Mean | SD | % Agree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing employment opportunities | 3.57 | 1.57 | 61.9 |

| Improving opportunities to invest | 2.81 | 1.34 | 33.3 |

| Encouraging the residents to join tourism industry | 2.95 | 1.37 | 38.1 |

| Increasing price of land and housing | 1.98 | 1.19 | 14.3 |

| Increasing cost of living | 2.00 | 1.03 | 9.5 |

| Improving public utilities infrastructure | 3.00 | 1.21 | 28.6 |

| Increasing the availability of recreational facilities | 2.33 | 1.37 | 19.0 |

| Improving quality of police protection | 3.10 | 1.12 | 23.8 |

| Improving quality of fire protection | 3.55 | 1.21 | 50.0 |

| Increasing the demand for historical and cultural exhibits | 3.65 | 1.33 | 50.0 |

| Encouraging residents’ participation in cultural activities | 3.10 | 1.37 | 45.0 |

| Preserving cultural identity of local residents | 2.48 | 1.31 | 19.0 |

| Increasing crime and robberies | 2.38 | 1.26 | 14.3 |

| Harming village’s intrinsic culture | 2.95 | 1.22 | 28.6 |

| Helping to restore lost culture | 3.15 | 1.47 | 40.0 |

| Increasing vandalism | 2.95 | 1.01 | 28.6 |

| Increasing invasion of privacy | 4.48 | 0.91 | 80.9 |

| Increasing the amenities for residents | 2.24 | 1.35 | 19.1 |

| Preserving the village environment | 2.90 | 1.39 | 33.3 |

| Increasing availability to repair/reconstruction | 2.86 | 1.47 | 38.0 |

| Congesting traffic condition | 3.65 | 1.54 | 65.0 |

| Increasing litter | 4.00 | 1.39 | 76.2 |

| Increasing noise pollution | 3.38 | 1.54 | 52.3 |

| Increasing overcrowding | 3.86 | 1.13 | 61.9 |

| Impact Variables * | Mean | SD | % Agree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction of Quality of Life | |||

| I am proud of living in Hahoe Village | 3.85 | 1.44 | 65.0 |

| Hahoe Village is a good place to live | 3.65 | 1.25 | 55.0 |

| WHS designation improves quality of life | 2.79 | 1.33 | 21.1 |

| I will live in Hahoe Village rest of life | 4.40 | 1.25 | 85.0 |

| Support for Preservation and Tourism Development | |||

| WHS designation brings positive impacts on resident’s lives | 3.24 | 1.55 | 42.8 |

| Village needs more preservation | 4.86 | 0.47 | 94.8 |

| Economic benefits are more important than preservation | 2.40 | 1.29 | 20.0 |

| Positive impacts of tourism outweigh negative impacts | 3.60 | 1.58 | 55.0 |

| Tourism is one major industry in Hahoe Village | 4.29 | 0.94 | 76.1 |

| I want to join tourism industry | 4.24 | 1.42 | 80.9 |

| WHS designation brings positive tourism impacts | 3.57 | 1.54 | 57.2 |

| Village needs more tourism development | 4.81 | 0.39 | 100.0 |

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S. World Heritage Site Designation Impacts on a Historic Village: A Case Study on Residents’ Perceptions of Hahoe Village (Korea). Sustainability 2016, 8, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030258

Kim S. World Heritage Site Designation Impacts on a Historic Village: A Case Study on Residents’ Perceptions of Hahoe Village (Korea). Sustainability. 2016; 8(3):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030258

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Soonki. 2016. "World Heritage Site Designation Impacts on a Historic Village: A Case Study on Residents’ Perceptions of Hahoe Village (Korea)" Sustainability 8, no. 3: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030258

APA StyleKim, S. (2016). World Heritage Site Designation Impacts on a Historic Village: A Case Study on Residents’ Perceptions of Hahoe Village (Korea). Sustainability, 8(3), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030258