1. Introduction

Sales or marketing activities have been addressed in the literature as an indispensable component of value chains in industrial clusters. Intermediary businesses connecting local manufacturers and the international market are considered to be an important factor in the development of clusters [

1]. At present, multinational companies have tended to incorporate industrial clusters in developing countries into their global value chains through outsourcing production or contract manufacturing [

2,

3], which provides a boost to the commercialization of industrial clusters [

4] and to the regeneration [

5,

6] or upgrading [

7,

8] of these clusters. However, in the literature regarding industrial clusters in Western countries, little consideration has been paid towards the geographical distribution and location of small and medium sales agencies (SAs) that connect manufacturers to customers, and less is mentioned about specialized markets (SMs) as physical exchange platforms or spaces for SAs and their clients. In fact, studies on industrial clusters in developing countries, such as China, have pointed out that SMs and manufacturing clusters have been important driving forces in rural industrialization since the late 1970s [

9]. In fact, SMs have triggered the development of local manufacturing clusters or, conversely, local manufacturing clusters have brought about the prosperity in SMs, which also reveals that SAs in SMs have a close relationship with local manufacturing firms [

10].

SMs differ from the traditional business model in that they are a two-sided platform model in the small- and medium-sized-enterprise cluster, which provide services for both buyers and sellers and address procurement, price-setting and distribution [

11]. SMs are places for trading where a specific kind of utility commodity (in some cases mixed with a small amount of other kinds of commodities) are sold in bulk for both vast domestic and global markets [

11]. Those commodities are either made in neighboring areas or further away. According to the statistics from 2013, the average number of SAs (booths) in a SM in China is 612, while some may contain thousands [

12]. SAs are generally local independent merchants or sales departments attached to local manufacturers or even external producers in other places. They connect the local manufacturing with external clients and even foreign markets, and act as an important channel of products and information. The first generation of SMs in China formed spontaneously in the early 1980s at local (temporary) fairs. At that time, China implemented a unified distribution system of commodity circulation and prohibited the development of private-owned sectors. Therefore, those SMs were considered as a kind of institutional innovation [

13,

14,

15], and provided an important kind of sale channel for local family-owned factories. SAs in the SMs have their own factories or local suppliers, connect local production networks with customers outside the clusters [

11,

16], and consequently enhance the prosperity of local economies [

17]. As a result of those initial successful experiences, it became popular to construct various types of SMs to trigger local development, especially in regions with weak industrial base. Yiwu city in Zhejiang province and Linyi city in Shandong Province are two typical examples, well known as “commodity market”, situated in the north and south of China, respectively. Even recently, some cities in Mainland China, such as Shenyang in Liaoning Province, Changsha in Hunan Province, Changzhou in Guangdong Province, and Langfang in Hebei Province, have drawn up blueprints to construct or regenerate agglomerations of SMs in their urban planning [

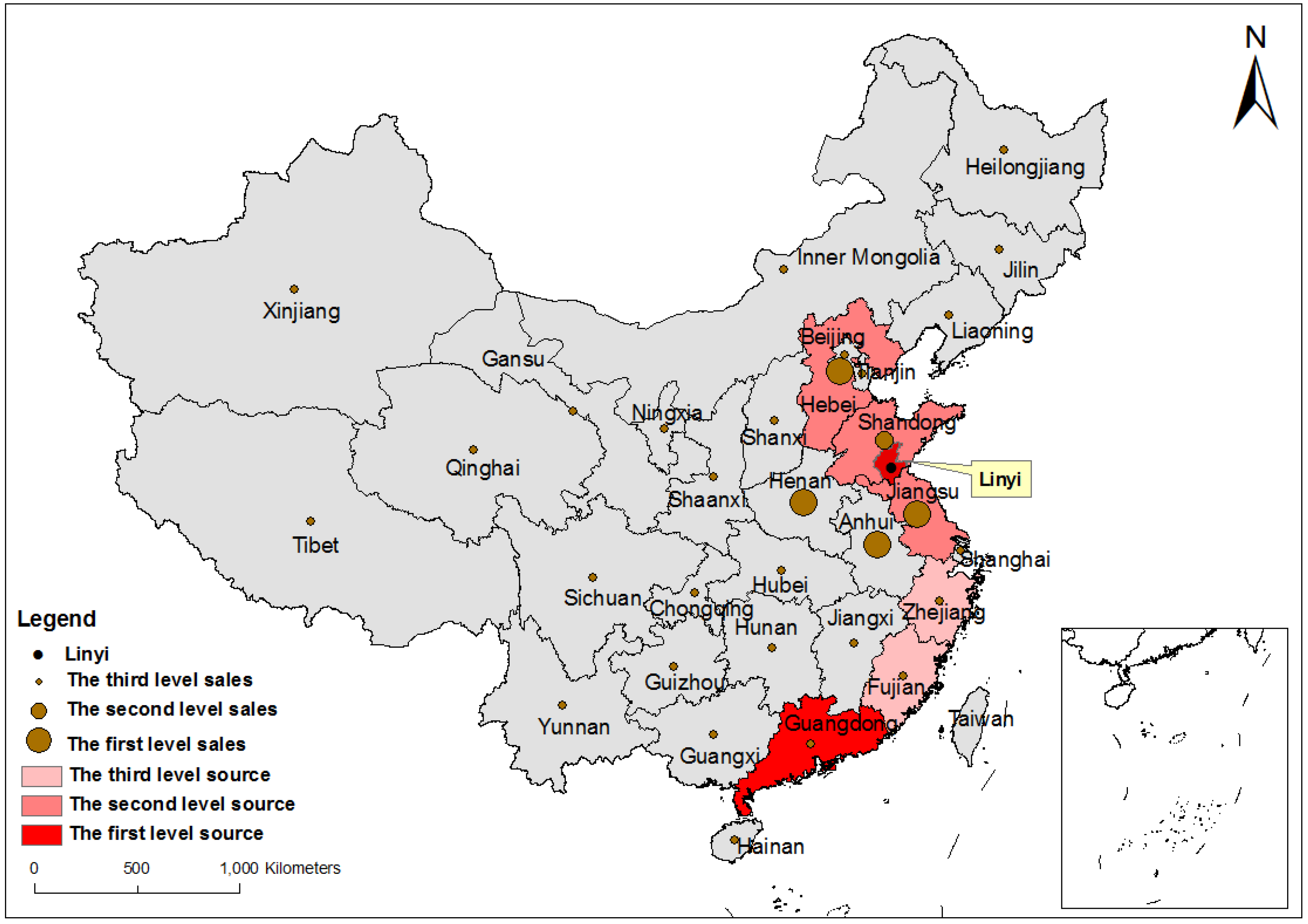

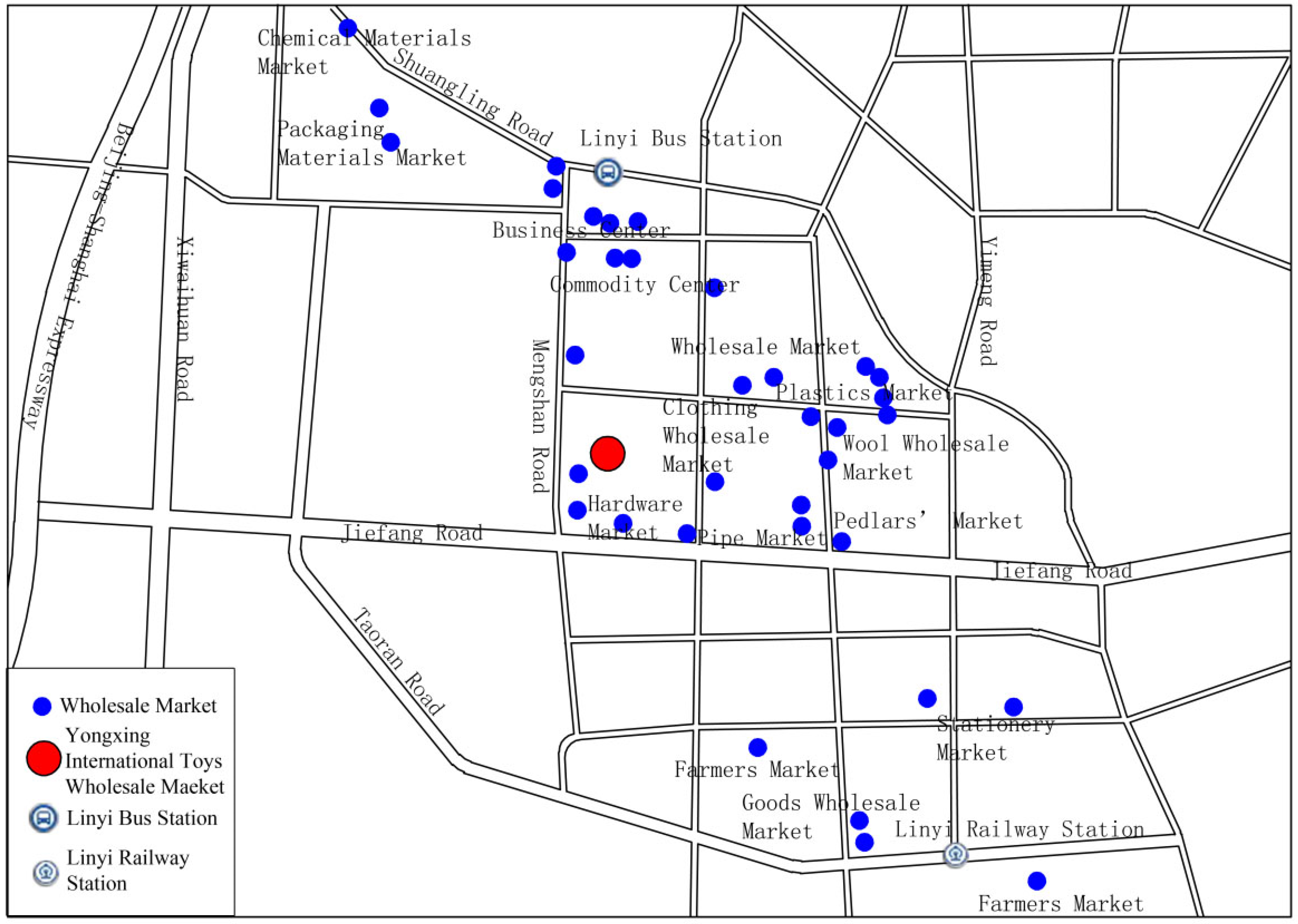

18].

In fact, manufacturing companies have become less dependent on local SMs as a result of the diversification of sales channels since the late 1990s, which has caused the degeneration or even demise of SMs as transaction platforms in the coastal areas of China [

17]. For a group of dominant SAs, constructing SMs in other regions at home or abroad was an alternative to the serious challenges being faced and was also a positive response to changing circumstances [

19]. SMs have encountered another round of crises recently due to the rising popularity of e-commerce. The transmission efficiency of business information has been improved greatly, and transaction costs of product exchanges have decreased. Therefore, the traditional advantages of physical SMs have been further weakened [

20]. In line with the fact that sales in commodity markets have decreased or even been forced to close, numerous “Taobao villages” (Taobao is the name of a most popular B2C e-commerce platform in China; a Taobao village is a village where the number of physical shops reaches more than 10% of the local households, and the transactions of electronic commerce amounts to more than 10 million yuan per year), which are more dependent on e-commerce than physical SMs have emerged throughout China. It is therefore urgent for both SMs and SAs to make a prompt transition. Some SMs have turned to focus on the development of information economy [

11], intensifying connections with foreign markets as a bridge between China and overseas in fragmented production [

16]. It has become the norm for a group of SAs to make expansions into e-commerce services [

20].

However, two important points have been neglected in the literature. The first concerns the function of SMs as a bridge between local manufacturers and external customers, and the interactions between SMs and their neighboring manufacturing clusters; while focusing little interest on those SMs which connect remote small- and medium-sized manufacturers with remote clients besides local clients. In fact, in under-developed areas in particular, local SMs were supposed to undertake the crucial role of being a trigger to local industrialization [

21]. Second, the literature discusses SMs as a whole and concerns itself little with the various kinds of actors in the SMs, such as SAs. SMs actually appear like “black boxes”. Especially under changing circumstances, it is not clear how those actors respond and what their effects on local economic development are as a consequence.

This paper focus on the response of traditional SMs to the changing circumstances in less industrialized areas, where SMs originally relied on far-way areas instead of local industrial clusters and SAs have been facing diluted profits from traditional manufacturing [

22]. According to the field survey, local SAs have been turning to the relevant product manufacturing, which has been paid little attention to in recent literature. The authors have concerned themselves with which factors drive SAs on SM-based clusters to incorporate manufacturing into their intra-firm value chains. Furthermore, which factors cause SAs to expand manufacturing scale and bring about the burgeoning of local manufacturing is also investigated.

Section 2 conducts a review of the literature and forms some hypotheses.

Section 3 covers the research area, methodology, and data collection.

Section 4 presents the data, analyses and results. The final section then draws conclusions and provides some discussions.

2. Literature Review and Main Hypotheses

The extension of value chains in SM-based clusters (SMBCs) to manufacturing can be understood as an upgrading of regional industries. Literature on industrial clusters discusses some innovation-related topics such as knowledge transfer and learning [

23]. Industrial upgrading has also been much debated in strands of literature on global production networks [

24,

25] (GPNs) or global value chains (GVCs) [

26]. From the perspective of GPN theory, chains and networks are merely organizational devices providing opportunities for actor-specific learning, practice, and upgrading [

27]. GPN-GVC studies focus on the strategic coupling of clusters and regions within global production systems [

28,

29], and demonstrate four categories of industrial upgrading [

26].

Much of the existing debates on GPNs and GVCs centers around the governance structures of three typical chains, modular, relational, and captive chains [

30], and relational network configurations [

31]. An updated GPN theory, called “GPN 2.0” by Yeung and Coe, takes an actor-centered focus, highlights the competitive dynamics (optimizing cost–capability ratios, market imperatives and financial discipline) and risk environments, and states their effects on shaping the actors’ organizational relationships within global production networks in different industries. Compared with previous GPN studies, GPN 2.0 states two relationships, intra-firm coordination and extra-firm bargaining, beyond inter-firm control and inter-firm partners. The latter two inter-firm relationships originate from the three types of chains as mentioned above.

Although global production networks are considered as cross-border organizational platforms, GPN theory also attempts to analyze regional development between and within countries in global production systems. Moreover, the updated GPN theory focuses much more on the actors and their organizational relationships shaped by “capitalist dynamics”, and intends to explore their ultimate effects on the developmental outcomes in different regions and countries. In fact, it provides an actor-relationship approach in analyzing cluster upgrading within cross-regional production networks (CRPNs) in a country like China, where there are economic, cultural, and institutional differences between different regions [

27,

32]. GPN 2.0 not only identifies diverse firm actors, ranging from lead firms, strategic partners, specialized suppliers and generic suppliers to customers, but also introduces non-firm actors, such as the state, international organizations, labor groups, and civil society organizations. However, it pays little attention to such firm or non-firm actors as the gatekeepers or intermediate agents who connect local clusters worldwide and whose importance is highlighted, especially in the learning dynamics of industrial clusters [

33].

The authors have selected SAs, local merchants with intensive relationships with the outside, as a targeted firm actor, in order to explore the upgrading of SM-based clusters within CRPNs. It is believed that SAs with a certain amount of capital and technical ability move into manufacturing out of economic interests or o avoid the large pressures from market competition [

34]. The pursuit of economic profit is related to the intra-firm factors, and the pressure from competition is most probably caused by a large number of local and external counterparts, and even from abroad (such as international buyers), and the emergence of e-commerce vendors. The increasing competition between local SAs and their counterparts leads to a change in their bargaining power with suppliers [

35]. In addition, although SAs can accumulate technical skills through self-learning or their own innovation, it is common practice for them to learn from their peers and longstanding partners. As a consequence, the authors of GPN 2.0 pay special attention to intra-firm coordination, local inter-firm relationships, and cross-regional inter-firm bargaining and partnerships.

2.1. SAs’ Motivations for Setting Foot in Manufacturing as Intra-firm Coordination

“Intra-firm coordination” refers to the internalization and consolidation of value activities, including management and logistics of production, design, research and development (R&D), and monitoring of quality standards and production outcomes within various actors [

27]. Through intra-firm coordination, various actors within GPNs can improve firm-specific efficiencies such as cost control, market responsiveness, and higher-quality products or services. Setting foot in manufacturing can be viewed as intra-firm coordination within SAs in the SMs, and it is reasonable to consider that benefits concerning firm-specific efficiencies or competitiveness, in turn become intra-firm motivations for SAs to take on such coordinated strategies.

As previously mentioned, a body of literature believes that that SAs move into manufacturing out of economic interests. It was common for SAs to move into production in the 1980s and 1990s in China when the country had a smaller economy and manufacturing yielded higher profits than ever. However, the situation has dramatically changed recently. As production costs have increased, the profits from traditional product manufacturing have declined. Some manufacturing companies have struggled to make changes, and others have even moved to neighboring countries to take advantage of lower production costs [

36]. Under such circumstance, it is in doubt as to whether or not the purpose of improving profits is strong enough for SAs to enter into the traditional manufacturing sector. From the perspective of transaction costs, it would be rational for SAs to move into manufacturing instead of completely relying on external suppliers when the administrative costs of internal production is less than the transaction costs of external purchasing [

37]. As a result, setting foot in manufacturing can be considered as SAs’ response in decreasing costs and strengthening their competitiveness (the so-called “cost–capability ratio” as stated by Yeung and Coe) even when there is little profit to be made from the traditional manufacturing.

Meanwhile, with the rapid development of e-commerce services and increasing diversity of demand, more and more small- and medium-sized manufacturers have turned to focus on small batch, customized, and timely production, and have paid more attention to new product development and innovation to obtain and sustain competitiveness [

38]. Accordingly, SAs setting foot in manufacturing could hardly survive the increasingly serious competition in manufacturing sectors without the capability of product innovation. From the viewpoint of transaction costs, innovative products are usually those with high asset specificity, and their transaction cost is higher than that of ordinary products [

37]. In this case, it is reasonable for SAs to choose self-production rather than outsourcing production for the sake of innovation protection and quality control of new products. The more non-standardized and innovative the products are and the more rapid the change of customers’ tastes, the more likely SAs will turn to depend on internal production.

Therefore, the authors put forward the following hypothesis.

H1: SAs setting foot in manufacturing is positively affected by their motivation for increasing firm-specific efficiency (e.g. cost control, market responsiveness, and higher-quality products or services) rather than that for obtaining greater economic profit in manufacturing.

SAs’ setting foot in manufacturing can lead to the emergence of manufacturing activity in SMBCs. The burgeoning of manufacturing and subsequent SMBC upgrading depends on the SAs’ manufacturing scale, which is also viewed as a continuous intra-firm coordination. Therefore, the authors believe that SAs’ manufacturing scale should be also taken into consideration. Internalization of manufacturing is one kind of firm growth or expansion, and so the intra-firm determinants sustained by SAs’ setting foot into manufacturing could also be attributed to SAs’ manufacturing scale. From the perspective of economic profits, it is reasonable to think the enlargement of production scale is down to chasing scale economies. However, under such circumstances as mentioned before, it is doubtful that SAs have significant enough motivations to expand manufacturing for scale economies. Moreover, according to Penrose’s view of firm growth [

39], unused resources within the firm originate sales, managerial, research or productive excess capacity. It is supposed that the motivations to use those unused resources to strengthen firms’ competitiveness lead to diversification or expansion of the firm.

Therefore, the authors put forward the following hypothesis.

H2: SAs’ manufacturing scale is positively affected by their motivations to increase their firm-efficiency by using competitiveness-related resources rather than that for obtaining scale economies.

2.2. Local Inter-Firm Relationships and Accessibility to SMBC-Specific Benefits

It is generally believed that external economies of scope are an excellent advantage of the agglomeration of various SMs in an area where there are intensive formal and informal intensive relationships. Customers can conveniently shop for a variety of commodities in the same place, which decreases the time and financial costs [

40,

41]. However, it is unclear whether or not external economies of scope have an important impact on expansion of SAs to related manufacturing. In terms of input-and-output linkage between different products in different local SMs, SAs in a specific SM are supposed to get products as raw materials or components from other SMs nearby, which makes SAs competitive when setting foot in manufacturing by reducing transportation and transaction costs as mentioned in literature on industrial clusters [

42].

The agglomeration of SAs in SMs can lead to fierce the competition between local SAs, forcing them to improve their innovation capability, which is common in manufacturing clusters [

42]. Meanwhile, SMs are a typical kind of information economy, which also bring about external economies of scale. Generally speaking, the agglomeration of SAs makes it more convenient for customers to get access to transparent information about homogeneous commodities for a low transaction cost [

43]. Moreover, local firms in the same location share value and cultural traditions in common, which is helpful in building up formal and informal trust-based relationships [

44]. The importance of these close and intensive relationships between local firms is highlighted in the decrease of transaction costs and transmission of knowledge and information in particular [

45,

46]. Once a SA takes the initiative to invest in related manufacturing and achieves great success in business, other SAs in the same SMs and even other SMs of different commodities in the locality would follow up its experience.

With an increasing number of SAs setting foot in manufacturing, local related manufacturing clusters are burgeoning, with external economies of scale being increasingly enhanced [

47]. It is easy for SAs and new entrants to get access to a skilled local labor pool, improve the production efficiency, and promote the growth of firms by virtue of local production networks [

48]. In addition, intensive local relationships between different organizations provide channels for the transmission of crucial knowledge and skills concerning related production for local manufacturers and SAs after setting foot in manufacturing. The dynamics of local learning are able to sustain a local competitive advantage [

49]. Based on the above theoretical analysis, the authors put forward the following hypothesis.

H3: SAs’ setting foot in manufacturing is positively affected by accessibility to SMBC-specific benefits from local inter-firm relationships.

For similar reasons concerning the context of raising H2, the accessibility to local resources or benefits probably has a positive effect on SAs’ manufacturing scale. Moreover, although Penrose highlights the importance of firm’s endogenous growth, she further states that the growth of firms may be consistent with the most efficient use of a society’s resources, and acknowledges the interaction between internal and external factors. Therefore, the authors put forward the following hypothesis.

H4: SAs’ manufacturing scale is positively affected by the accessibility to SMBC-specific benefits from local inter-firm relationships.

2.3. Dynamic Cross-Regional Inter-Firm Relationships and Accessibility to External Knowledge/Technology

The importance of innovation in regional development is highlighted in some strands of literature regarding industrial clusters, learning regions, and regional innovation systems. The inter-organizational networks are believed to underpin the flow of knowledge within and across regions [

50], and the dynamic relationships between economic globalization and regional development is one area in particular in which much attention has been paid [

28]. Cross-border linkages [

51], such as global pipelines [

23], and GPNs and GVCs [

52], discussed in the beginning of this section, are important channels for local firms in obtaining heterogeneous knowledge and information, and furthermore promote cluster upgrading [

53,

54]. In addition, competition between same-level suppliers and the high-level requirements for quality, force firms in the GVCs or GPNs to focus on innovation [

52,

53].

In fact, upgrading is a complicated process. Global technology forerunners tend to delimitate against the chances of being caught up by their suppliers in developing countries [

26]. Therefore, it is much easier for the latter to make process and upgrade their products than to carry out functional and chain upgrades [

26]. Another line of literature demonstrates that cross-regional production networks (CRPNs) within a nation provide more possibilities for firms in less developed countries to move up to higher value-added activities by embedding into national or regional value chains than into a GVC or GPN [

55]. The reason for this is because tacit knowledge is often embedded in the relationships between related firms with a common cultural background and is transmitted easily between firms in value chains within a country or region [

55]. However, later studies do not deny the feasibility of using the analytical framework of GPN theory to explore industrial upgrading and regional development.

It supposes that CRPNs make it possible for SAs to gain knowledge and skills for production from their suppliers. Moreover, the dynamics of inter-relationships between SAs and their suppliers across the region may have an impact on the extension of value chain to manufacturing. On the one hand, as more and more suppliers incorporate into the GPNs of global companies, or depend more on e-commerce services, their connections with SAs loosen; on the other hand, as SAs enter into manufacturing, in their suppliers’ eyes, the competition between them outweighs the benefits of cooperation. That means SAs would further expand the production scale to depend more on internal manufacturing, given their bargaining power and learning opportunities from their upstream suppliers decrease. Therefore, the authors put forward the following hypotheses.

H5: SAs’ setting foot in manufacturing is positively affected by the accessibility to knowledge/technology based on dynamic relationships with cross-regional suppliers.

H6: SAs’ manufacturing scale is negatively affected by the accessibility to knowledge/technology based on dynamic relationships with cross-regional suppliers.

4. Data Analysis and Results

This paper discusses the factors that exert influence on the expansion of SAs from wholesale to manufacturing and on the scale of internal production. Based on the literature reviewed in

Section 2, the authors selected three kinds of determinants, namely, individual motivations of entrepreneurial innovation, local agglomeration effects of SMs, and dynamic relationships within CRVCs, as independent variables, and defined “whether or not SAs set foot in related product manufacturing” and “the production scale of SAs” as the dependent variables, respectively.

4.1. Factors Affecting SAs to Investing in Manufacturing

According to the literature analysis in the second section, eight variables were selected as independent variables presenting individual motivations of intra-firm coordination, local inter-firm relationships for facilitation to get SMBC-specific benefits, and dynamic cross-regional inter-firm relationships for accessibility to crucial resources. “Sales duration”, “Size of SAs” and “Industry specialization” were the control variables, and “whether or not SAs set foot in related product manufacturing” as the dependent variable. All variables and their meanings, and their scores quantitative criteria are shown in

Table 2.

Based on the related data of 117 valid samples, the authors used the “Backward: LR” method of Binary Logistic Regression, which first starts with all variables in the regression equation, and then removes the independent variables that have no significant effect on the dependent variable according to the probability value of statistic derived from the Maximum Likelihood Estimation. The judgment probability is set as 0.05, so that the performance of the model is more optimized. The logistic regression model estimation results are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

According to

Table 4, the overall fitting degree is good (X

2 = 83.509, P = 0.000), which shows that the independent variables on the whole have a significant effect on the dependent variable (P < 0.05). Only one independent variable, namely lr2, had a significant effect on the dependent variables (P < 0.05), while the other independent variables did not have significant effect. According to the probability value of statistics derived from the Maximum Likelihood Estimation, the irrelevant independent variables were removed and the optimized results are shown in

Table 4.

The optimized model result shows that the effect of im2, lr2, and dcrr2 on the dependent variable is clear, and the corresponding regression coefficients are 0.704, 1.358, and 0.839 respectively. It indicates that the three factors, “reducing transaction costs of innovative products”, accessibility to “local resources”, and “skill acquisition from suppliers” drive SAs to invest in related manufacturing. They, respectively, represent “individual motivations of intra-firm coordination” (related to the firm-specific efficiency), “accessibility to SMBC-specific benefits from local inter-firm relationships” and “accessibility to knowledge/technology based on dynamic cross-regional inter-firm relationships”, which verify hypotheses 1, 3 and 5. The coefficient of lr2 is higher than dcrr2 and im2, which means that accessibility to “local resources” is the most significant, and “accessibility to SMBC-specific benefits from local inter-firm relationships” play a much more important role than “accessibility to knowledge/technology based on dynamic cross-regional inter-firm relationships” and “individual motivations of intra-firm coordination” in driving SAs to invest in the manufacturing sector. In fact, due to a variety of different SMs nearby, toy SAs can easily get access to raw materials at a low cost of transportation and transaction. The external economies of scope in the agglomeration of SMs provide an important precondition or advantage for SAs in making an expansion into manufacturing.

Long-term business collaborations with trans-local toys manufacturers are an important learning channel for SAs to acquire indispensable technical support in the initial stages of entering into manufacturing. Despite the fact that more than half have their own ideas of product design in general as mentioned below, 23 SAs setting foot in manufacturing (making up 42.6% of the similar SAs) claimed in the questionnaire survey that they remained the business cooperation with their previous trans-local suppliers for access to new information about product development and design The subsequent interviews further indicated that local toy SAs were not bold when making investment in manufacturing without acquiring knowledge about it first. There is little evidence to indicate that those suppliers have turned to depend more on other sales channels than traditional SMs.

No matter whether they invested in manufacturing or not, almost all the SAs surveyed claimed that there is very little profit in toy manufacturing. This is the reason why the variable, “gaining profit”, is not significant to the dependent variable, and it can also explain the reason why the dependent variable “peer’s demonstration” has no significant relationship with the business expansion of SAs. Meanwhile, due to intensive contact sub-level distributors all over the country, some toy SAs are sensitive to the market changes and often figure out innovative ideas about the new product development. 35 SAs setting foot in manufacturing (making up 64.8% of the similar SAs) claimed in the questionnaire survey that they often created some good ideas of product design by virtue of their marketing experiences for years. Those SAs prefer to adopt internal production rather than outsource production in case their innovations are leaked out.

Interestingly, although the two variables concerning individual motivations, “prompt response to the market change” and “gaining profit”, have no significance on SAs setting foot in manufacturing in the model, the questionnaire result indicates that internal production does improve the competitiveness and the profit levels for SAs.

Table 5 shows that the majority of SAs in the questionnaire survey claimed that their competitiveness had improved to some extent after moving to internal production, sales and profits had increased, and accordingly external purchase of toys had decreased. Furthermore, during the subsequent interview, a couple of SAs mentioned that increasing uncertainty in the toy market requires a prompt response from SAs to the rapid changes in demands. As a consequence, SAs adopt low-volume production for the initial stage of launching new products and then promptly move to organize mass production once those new products are successful. Otherwise, SAs would not be able get much economic return as their creative ideas would be widely copied in a short time. That situation requires geographical proximity of sales to toy production, which helps improve their competitiveness.

4.2. Factors Affecting the Production Scale of SAs

The 54 SAs setting foot in manufacturing showed a big difference in production scales. In terms of the percentage of internal production to the total sales volume, nearly half of these SAs (25) reached more than 30%, and a couple of SAs even amounted to more than 90%, while some SAs account for less than 10%. In this section, the authors explore which factors affect the production scale of SAs after moving into manufacturing. Nine variables have been selected as independent variables, which respectively present individual motivations, local agglomerations and dynamic trans-local relationships as mentioned before, with “technical change” and “financial capital” added as two control variables; “the scale of internal production” is the dependent variable. All variables and their meanings are explained in

Table 6.

The estimated results of the logistic regression model are shown in

Table 7 and

Table 8.

Table 7 shows that the overall fitting degree is not good (X

2 =17.499, P = 0.095), which indicates that the whole independent variables do not have a significant effect on the dependent variable (P > 0.05). Independent variables LR1and LR4 have a significant effect on the dependent variables (P < 0.05). According to the probability value of statistics derived from the Maximum Likelihood Estimation, the irrelevant independent variables are removed and the optimized results are shown in

Table 8.

Table 8 shows as a whole, the independent variables have a significant effect on the dependent variable (P < 0.05). The optimized model result shows that only LR1, LR3 and LR4 are significant at the 5% level, and their corresponding regression coefficients are 1.416, 0.878 and 1.115, respectively. That is to say, accessibility to “local resources”, “local learning”, and “local labor resources” encourage SAs to expand the scale of manufacturing. These three factors are part of the local cluster effects, which verifies hypothesis 4 that accessibility to SMBC-specific benefits from local inter-firm relationships positively impacts on the scale of SAs’ internal production. The authors made a further comparison between the two groups of samples. The results show that for SAs whose production percentage is more than 30%, the means of LR1, LR3 and LR4 are, respectively, 4.7, 3.8, and 3.4, which is much higher than those of SAs with less than 30% (the means of the three variables are 4.1, 3.3, and 2.6, respectively).

The variable “(accessibility to) local resources” is closely related to the external economies of scope in agglomeration of SMs. Local related SMs not only provide raw materials and components for SAs to set foot in toy manufacturing, but also have a positive effect on the expansion of the production scale. Local learning between SAs does not have a significant bearing on the decision about whether or not SAs set foot in manufacturing, but local mutual learning between SAs setting foot in manufacturing can promote the expansion of the production scale. Although the variable “local lower logistics costs” is not significant in the model, subsequent interviews show that fast local logistics services and its lower costs make it convenient for SAs to purchase some raw materials and toys from outside.

Individual motivations of intra-firm coordination can inspire SAs to set foot into related manufacturing; however, their subsequent impact on the expansion of production scale is not significant. That probably implies that SAs’ administration capabilities are more important than their motivations in realizing an expansion of production. Despite the fact that accessibility to knowledge/technology based on dynamic inter-firm relationships across regions have no significance on the production scale, a couple of the SAs interviewed responded by saying that they still paid attention to business cooperation with trans-local suppliers as it helps them get access to the updated information about new products. SAs often purchase toys in small quantities and promptly organize internal production once those products are welcomed in the market. In fact, local manufacturers often encounter problems concerning complicated skills, product design, and crucial technologies, and have difficulties in learning those from their suppliers across regions. This is particularly true in the manufacturing of electronic toys.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Western cluster literature mentions little about SMs and the geographical location of SAs. Chinese scholars have noted the role of SMs in the burgeoning of industrial clusters and have placed an emphasis on the interdependent and co-evolutionary relationships between prosperous SMs and mature industrial clusters nearby, but ignored the response of SAs in the SMs to the changing circumstances and their importance in regional development. One contribution of this paper is to fill in the gap between the existing research on cluster upgrading and Chinese practice through providing the case of Linyi where SMBCs incorporate manufacturing into local value chains. Another contribution is to use the updated GPN theory to set up the analytical framework, and to explain how competitive dynamics and risk management shape the four types of relationship, and then have an effect on local development. The empirical results show that individual motivations of intra-firm coordination, regional inter-firm relationships and cross-regional inter-firm relationships have a significant and positive impact on the upgrading of local industrial clusters so as to sustain local competitiveness. Moreover, it also demonstrates that SAs could trigger the burgeoning of industrial clusters and speed up the process of industrialization through their investments in manufacturing in less-developed industrialized areas. The SAs in SMs actually act as the intermediate agents or the gatekeepers between local production networks and global flows in the cluster learning literature, whose role is neglected in GPN 2.0 theory. In addition, there is a group of small- and medium-sized business trade cities in China, especially for those newly burgeoning e-commercial towns without strong economies and those with emerging economies. The case of Linyi provides experiences for those places to reshape regional competitiveness on the basis of adding advantages through trade.

In the case of Linyi, three important points are worth being highlighted. First, in terms of such kind of traditional products as toys, due to shrinking profit margins, intensifying competition and rapid changes in consumer tastes, it is preferable for the increase in efficiencies or firm competitiveness rather than simple pursuit of economic profit that encourages SAs to move into manufacturing. Therefore, innovation-based internal production could sustain SAs’ competitiveness through the improvement of product quality and instantly responding to changing situations. Second, agglomeration of various kinds of SMs in the same place and the local inter-firm relationships within SM-based clusters facilitate access to material and human resources with lower manufacturing costs, and production knowledge and technologies for an expansion of manufacturing scale, which is beneficial to reshaping local competitiveness, whereas an isolated SM cannot easily benefit from these advantages. Mutual learning between toy SAs setting foot in manufacturing and new entrants as manufacturers are an important channel for the sharing of knowledge, and so it is helpful for SAs to make expansions in terms of production scales. That implies it is necessary to improve local innovation networks. Third, a dynamic relationship with cross-regional suppliers is an important channel of knowledge transmission; however, it cannot guarantee efficient access to core technologies and crucial knowledge for SAs without knowledge-oriented cooperation. That probably means it is indispensible to establish cross-regional learning channels to further strengthen the competitiveness of SAs and SMBCs.

Some issues worthy of further discussion remain. First, although this paper uses an analytical framework on the basis of GPN 2.0 theory, there is no direct linkage between local SAs in Linyi and foreign multinational companies. The result is probably different if such international linkages exist. Second, extra-firm partners mentioned in GPN2.0 theory are not taken into consideration in this paper. The authors focused on the CRCV but have not covered external learning channels with knowledge institutions as the preliminary survey evidence, which showed that local SAs have little interest in establishing external technology-based cooperation. The emergence and dynamics of such relationships for access to external knowledge deserves concern. Additionally, local authorities and other institutions are not integrated into the analytical framework. Although almost all SAs in the survey claimed that local governments made little effort in promoting the development of toy manufacturing, it has been reported that the Linyi municipal government has proposed industrial policies and established industrial parks to “stimulate prosperity in manufacturing sectors by taking advantage of local SMs strategy”. Finally, the relationships between SAs and local toy factories in the suburban areas are worth investigation in order to gain a better understanding of the role of SAs in local development.