Overcoming Ex-Post Development Stagnation: Interventions with Continuity and Scaling in Mind

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Scale: Temporal and Spatial Components

2.1. Temporal Scale Considerations

2.2 Spatial Scale Considerations

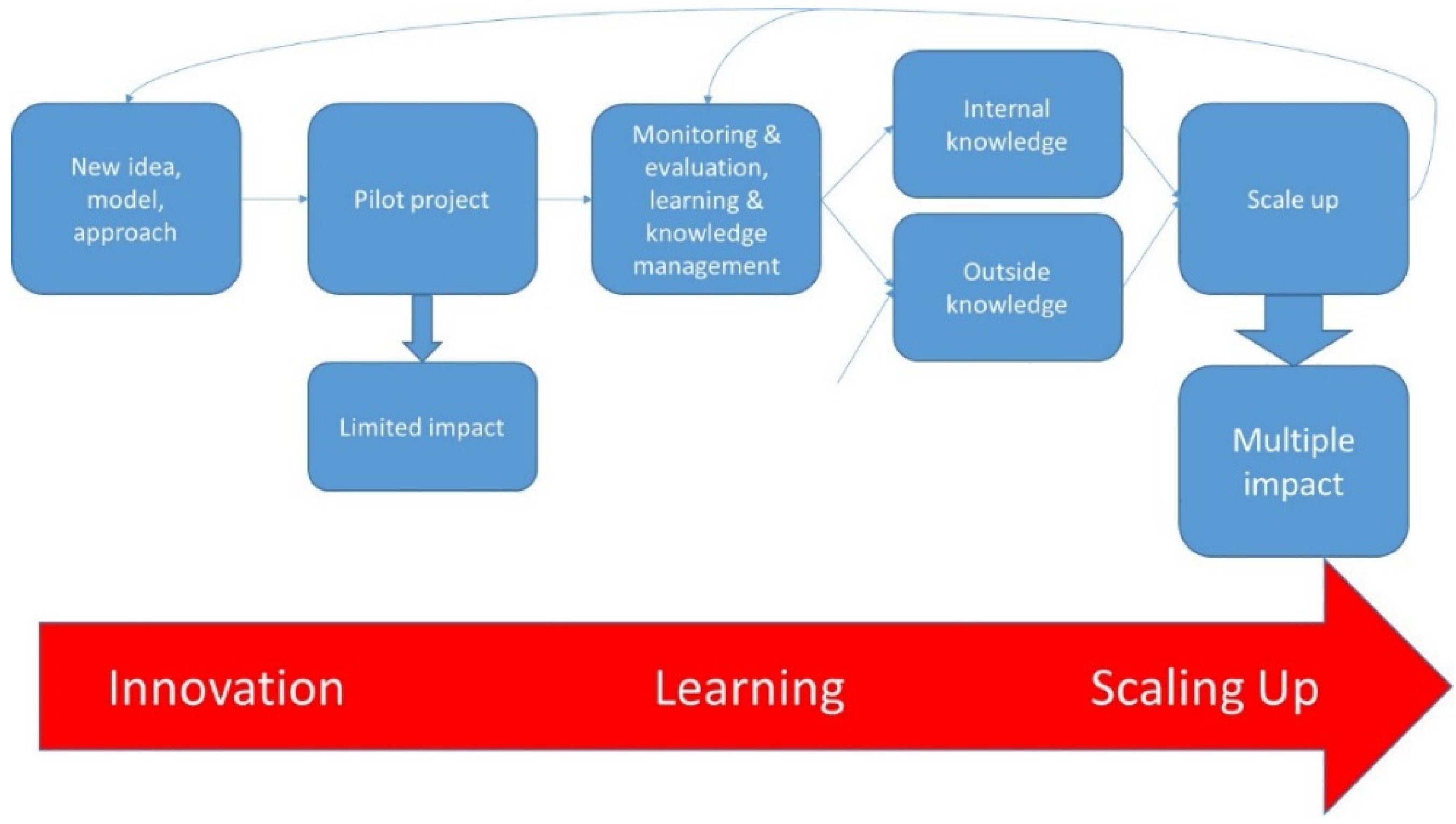

3. Scaling of Interventions

3.1. A Review of Various Forms of Scaling

3.2. History, Status and the Development Sector

3.2.1. History and Status

3.2.2. Development Sector Experiences

4. Scaling-within: A New Concept for Consideration

4.1. A Brief Overview of the Concept

- •

- The promotion of continuity between the closing stages of a formal full-scale development intervention and the introduction of scaling-within activities (scaling-within activities commence as a previous intervention’s activities are winding down).

- •

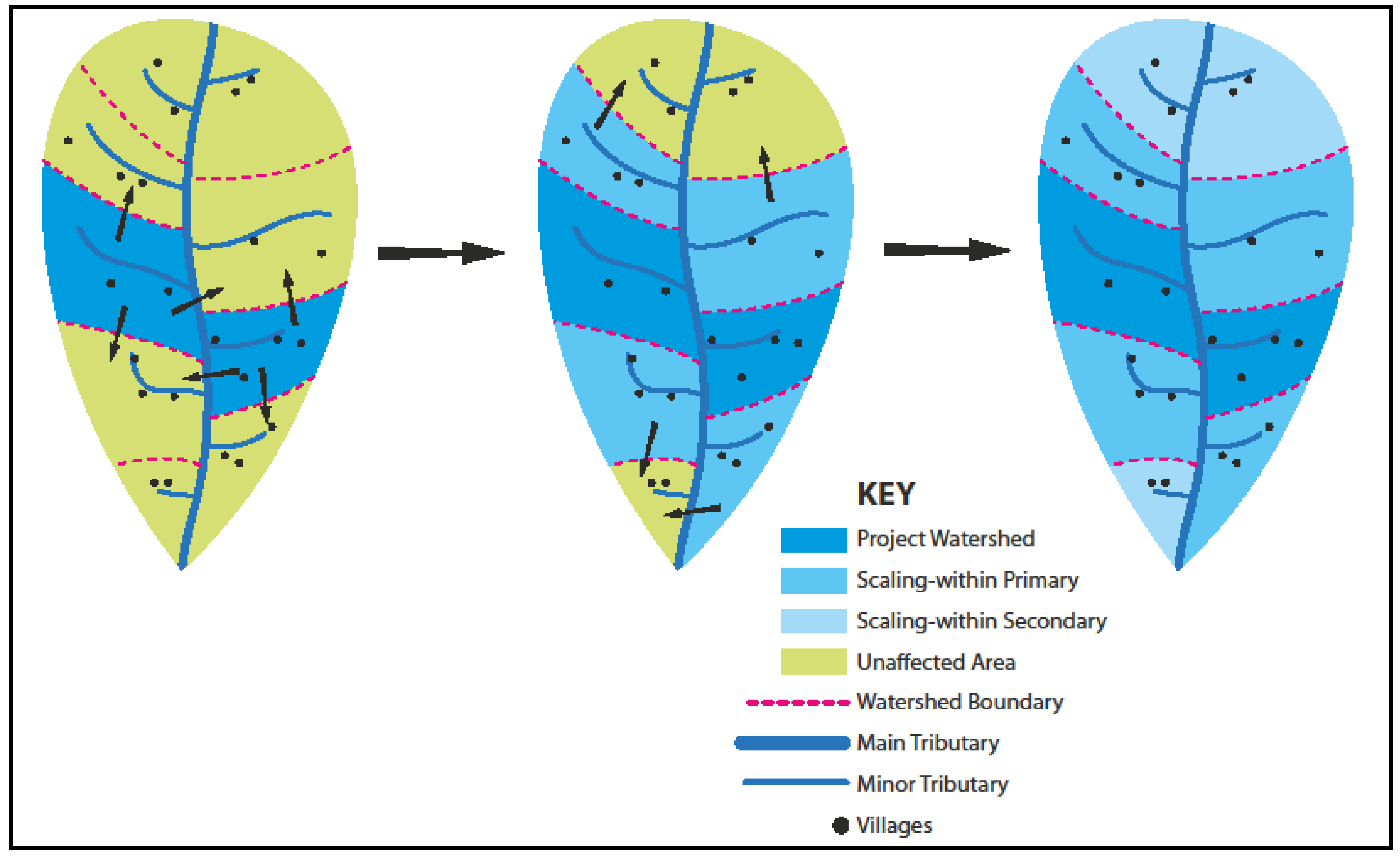

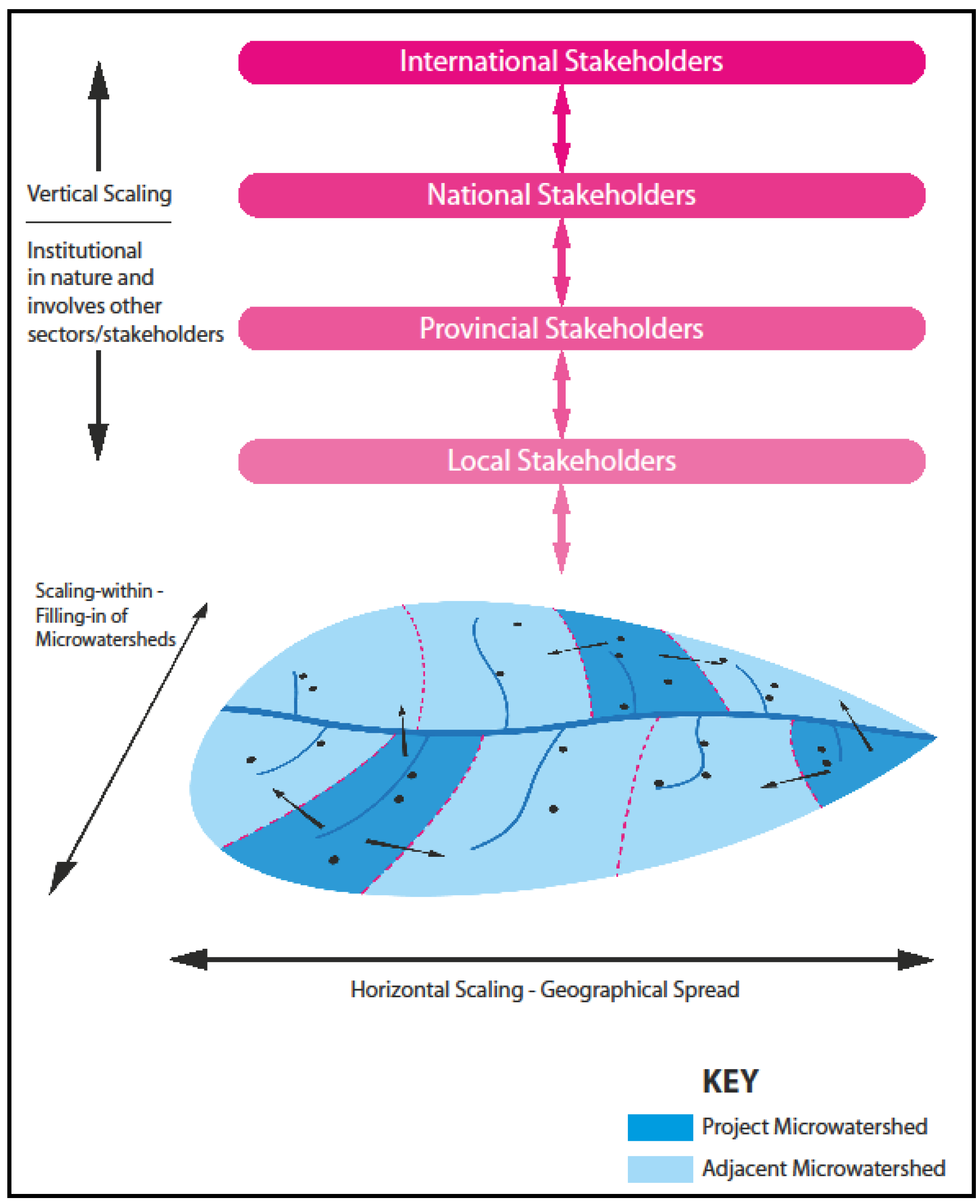

- Requiring that the intervention be in a space where there are gaps to be filled at lower hierarchical levels and there is demand for them to be filled. This may constitute no planned expansion into “new” areas but instead promotes in-filling within the quantitative, organisational, political, and institutional boundaries defined by the preceding project (ultimately the watershed (river basin)) as illustrated in Figure 2. This avoids the problem of “scale forcing”, where boundaries need to be expanded to take account of higher level processes. Infilling may occur from multiple nuclei (multiple micro-watersheds as illustrated in Figure 2), as opposed to typical “scaling-out” which is often perceived to be an “outwards-focused spread from a small nucleus of activity” [90].

- •

- The process could be demand-driven by the adopting communities. This would include an objective “simplification” [8] of activities to only include those elements of the original intervention which are requested by communities and are cost-effective for producing the desired results (i.e., acceptance of some activities/components and rejection of others). At the same time, space for functional scaling could be possible as adopting communities evolve in their knowledge and needs. This utilises the theory of imitation, where replication with adaptation to specific contexts and situations occurs beyond a time-bound intervention [37]. Community driven development should occur within the broader framework established during the initial intervention.

- •

- Scaling-within contains some similarities to scaling-down as well as to forms of scaling-up including spread, diffusion and spillover. However, social process innovations targeted by scaling-within may require a more supported approach. Case study evidence and literature review suggest that without guidance and impetus to promote ex-post continuity, little diffusion and spillover typically occurs. Informal networking, in partnership with existing or new collaborators, could occur within a broader scaling-within framework.

4.2. Why Scaling-within?

4.2.1. Outstanding Need

4.2.2. Limited Literary Discourse and Empirical Evidence

4.2.3. Strong Potential, Tempered by Barriers

4.3. Scaling-within—The What and How

- •

- Facilitation of community access to business/personal loans.

- •

- Promotion of regional subsidies/incentives for livelihood improvement.Create conditions conducive for small enterprises to be established and engage in livelihood improvement service provision beyond project zones.

- •

- Establishment of marketing channels.Case-study projects provided the potential to link local communities with regional industries/private sector for value-adding activities. If activated, this may help address the over-reliance on primary industry found in many rural areas and promote income diversification [121].

| Project-Period | Proposals-for-Incorporating-Scaling-within-Opportunities |

|---|---|

| Ex-Ante-&-During-Project | Design

|

Training

| |

Enterprise

| |

Finance

| |

| Ex-Post | Training

|

Enterprise

| |

Finance

| |

Technical

|

5. Assessing Scaling-within Against a Framework Drawn from Literature

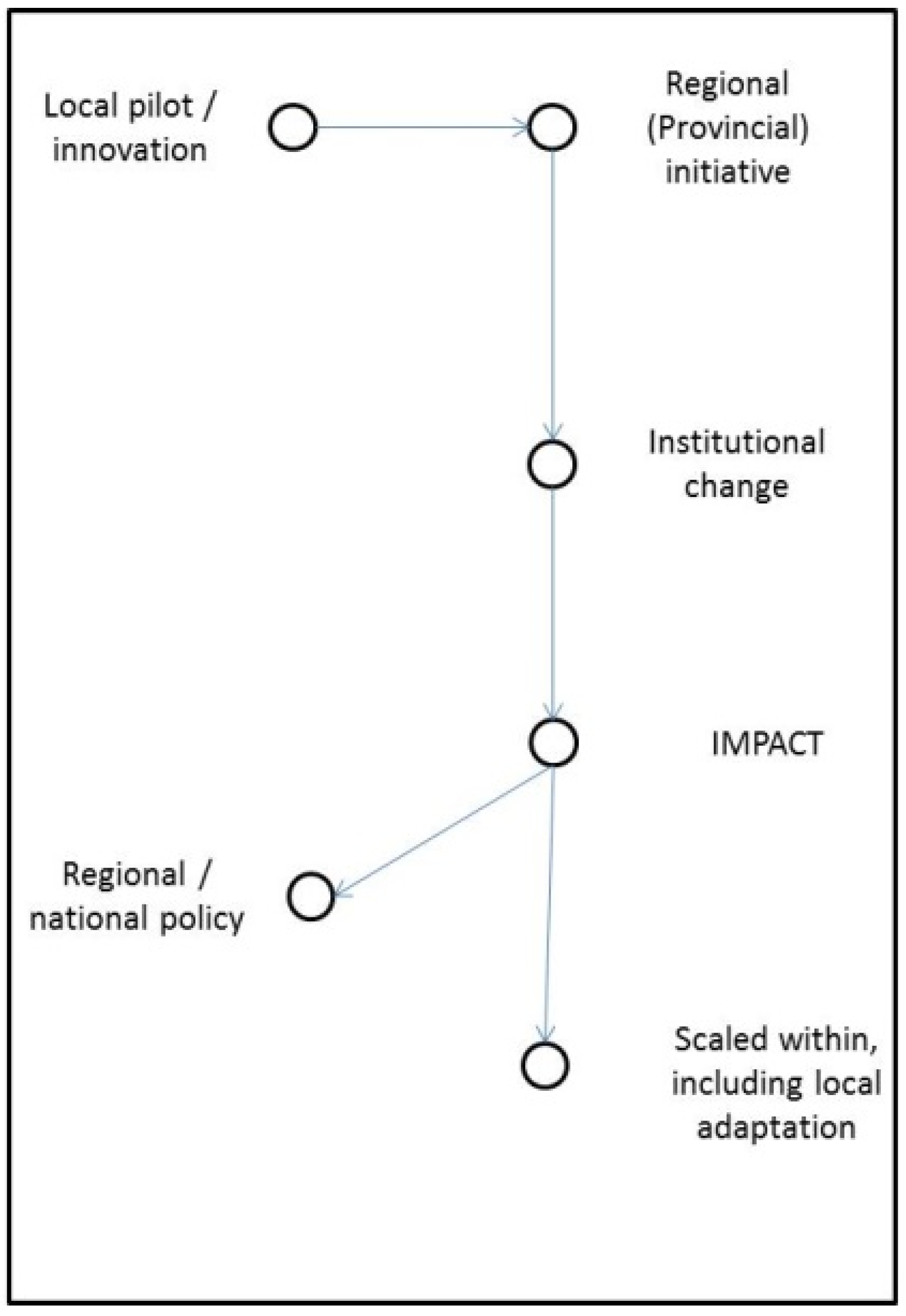

5.1. Pathways for Scaling-within

5.2. Drivers for Scaling-within

5.3. Spaces for Scaling-within

| Organization/Scheme | Description-of-Potential |

|---|---|

| International Donors |

|

| Regional Enterprise Development Organizations |

|

| National Commercial/Agricultural Banks |

|

| Watershed Trust Funds |

|

| Micro-finance Schemes |

|

| Private Sector Encouragement |

|

| Government Incentives/Subsidies |

|

| Administrative Level | Organizations | Potential Roles & Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| International/National |

|

|

| Regional |

|

|

| Local |

|

|

6. Caveats and Limitations

- •

- Chandy et al. [6] describe three critical characteristics of contemporary international aid architecture: (i) typically, aid interventions are very small and official data point to a steady fall in the average size of activities over time; (ii) interventions tend to have a short duration (for a sample of OECD and multilateral agency projects in 2010, mean length was 20 months, with half occurring within a single year); and (iii) interventions are largely discrete and disconnected from each other both within and across time. Whilst on one hand these increasingly fragmented development trends may justify scaling-within as one option to promote integration of continuity in the sector, they also pose a challenge if the concept needs to be effective at smaller scales (where the concept has not been tested theoretically nor practically).

- •

- Incorporating a scaling-within plan into an initial intervention may take some convincing of project proponents and additional pre-planning. Alternatively, if such provisions are not incorporated into the initial intervention, scaling-within can still occur but may require a confirmation of institutional and governance arrangements and more training and support for communities and local authorities.

- •

- Scaling-within is not proposed as a substitute for other forms of scaling-up or scaling-down—in fact it incorporates components of both. In particular, the authors recognise that the large-scale case studies reviewed involved some initial pilot testing and confirmation of concepts in practice prior to being applied at scale.

- •

- To avoid Type 2 scaling errors (as described earlier in this paper), scaling-within may only be recommended where the initial intervention has been deemed “successful”. The authors acknowledge the potential subjectivity of success and that metrics or some other form of stakeholder agreement mechanism could be developed to judge whether or not an intervention should be scaled-within. There are unavoidable linkages to the approach, structure and outputs/outcomes of the initial intervention and ideally, the scaling-within stage should be planned as a possibility for continuation of the initial intervention.

- •

- Related to a determination of “success”, scaling-within is dependent upon the comprehensiveness of the M&E conducted prior to and during the initial intervention. The more information that is available about the intervention and the communities, the more targeted the scaling-within can be.

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development (OECD). Quality Standards for Development Evaluation; DAC Guidelines and Reference Series; Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results Based Management; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gundel, S.; Hancock, J.; Anderson, S. Scaling-up Strategies for Research in Natural Resources Management: A Comparative Review; Natural Resources Institute: Chatham, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, E.J. Evaluation Methodology Basics: The Nuts and Bolts of Sound Evaluation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development (OECD). The DAC Guideline Strategies for Sustainable Development; International Development: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfensohn, J.D. A global life. In My Journey among Rich and Poor, from Sydney to Wall Street to the World Bank, 1st ed.; Public Affairs, Perseus Books Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chandy, L.; Hosono, A.; Kharas, H.; Linn, J. Getting to Scale: How to Bring Development Solutions to Millions of Poor People; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Guidance Note, Scaling-up Development Programmes; Poverty Reduction Unit: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, L.; Kohl, R. Scaling-up—From Vision to Large-scale Change a Management Framework for Practitioners; Management Systems International: Arlington, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vreugdenhil, H.; Taljaard, S.; Slinger, J.H. Pilot Projects and Their Diffusion: A Case Study of Integrated Coastal Management in South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Delegation Evaluation Report, Eastern Anatolia Watershed Rehabilitation Project; Report No. 111294 TU; Europe and Central Asia Region: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Van Sandinck, E.; Weterings, R. Maatschappelijke Innovatie Experimenten: Samenwerken in Baanbrekende initiatieven; Koninklijke Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2008. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Vreugdenhil, H.; Slinger, J.H.; van Daalen, E. Do we need a new management paradigm in river basin management? The missing link for socio-ecological system health. In Proceedings of Freude am Fluss Closing Conference, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 22–24 November 2008.

- Independent Evaluation Group (IEG). Annual Review of Development Effectiveness, Achieving Sustainable Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roob, N.; Bradach, J.L. Scaling What Works: Implications for Philanthropists, Policymakers, and Nonprofit Leaders; The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation and The Bridgespan Group: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Evaluation Group (IEG). An Evaluation of World Bank Support 1997–2007; Water and Development, World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, R.P.J.M. Niche accumulation and hybridisation strategies in transition processes towards a sustainable energy system: An assessment of differences and pitfalls. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2390–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.; Howlett, M. The lesson of learning: reconciling theories of policy learning and policy change. Policy Sci. 1992, 25, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Department for International Development (DFID). Multilateral Aid Review Update: Driving Reform to Achieve Multilateral Effectiveness. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/multilateral-aid-review-update-2013 (accessed on 4 July 2014).

- Darghouth, S.; Ward, C.; Gambarelli, G.; Styger, E.; Roux, J. Watershed Management Approaches, Policies and Operations: Lessons for Scaling-up; Water Sector Board Discussion Paper Series, Paper No. 11; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, M. Reforming Watershed Restoration: Science in Need of Application and Applications in Need of Science. Estuar. Coast. 2009, 32, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, C.; Curtis, A.; Stankey, G.; Schindler, B. Adaptive Management and Watersheds: A Social Science Perspective. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2008, 44, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, H.M.; Ffolliott, P.F.; Brooks, K.N. Integrated Watershed Management—Connecting People to Their Land and Water; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, S.P.; Sreedevi, T.K.; Rockstrom, J.; Ramakrishna, Y.S. Rainfed agriculture—Past trends and future prospects. In Rainfed agriculture: Unlocking the Potential; Wani, S.P., Rockstrom, J., Oweis, T., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2009; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, R.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Navigating Socio–Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, B.T. Sustainability Dynamics of Large-Scale Integrated Ecosystem Rehabilitation and Poverty Reduction Projects. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, B.T.; Guthrie, P.M. Phased, Large Scale Approaches to Integrated Ecosystem Rehabilitation & Livelihood Improvement—Review of a Chinese Case study. Agric. Sci. Res. J. 2011, 1, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller, B.T.; Cruickshank, H.J.; Guthrie, P.M. Large scale ecosystem rehabilitation and poverty reduction programmes: Ex-post sustainability assessment of a Chinese case study. In Proceedings of the 6th Dubrovnik Conference on Sustainable Development of Energy, Water, and Environment Systems, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 25–29 September 2011.

- Liu, J.D. Learning How to Communicate the Lessons of the Loess Plateau to Heal the Earth; Environmental Education Media Project (EEMP), Earth’s Hope: Mongolia Steppe, Mongolia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Scaling-up the Impact of Good Practices in Rural Development: A Working Paper to Support Implementation of the World Bank’s Rural Development Strategy. Report Number 26031. Agriculture and Rural Development Department; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P.P.; Jalal, K.F.; Boyd, J.A. An Introduction to Sustainable Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marschinski, R.; Behrle, S. The World Bank: Making the Business Case for Environment. Avalible online: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/ffu/akumwelt/bc2005/papers/marschinski_behrle_bc2005.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2009).

- Varley, R.C.G. The World Bank’s Assistance for Water Resources Management in China; The World Bank Operations Evaluation Department: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, U.; Volk, M. Meso-scale landscape analysis based on landscape balance investigations: Problems and hierarchical approaches for their resolution. Ecol. Model. 2003, 168, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penning de Vries, F.W.T. Response to Land Degradation; Bridges, E.M., Hannam, I.D., Roel Oldeman, L., Penning de Vries, F.W.T., Scherr, S.J., Sombatpanit, S., Eds.; Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, C.; Mandondo, A.; Moriarty, P. The Question of Scale in Integrated Natural Resource Management. In Integrated Natural Resource Management, Linking Productivity, the Environment and Development; Campbell, B.M., Sayer, J.A., Eds.; Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI): Wallingford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, A.; Hjorth, P. Planning for Sustainable Development: A Paradigm Shift towards a Process Based Approach. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banuri, T.; Najam, A. Civic Entrepreneurship—A Civil Society Perspective on Sustainable Development; Gandhara Academy Press: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Eckman, K.; Gregersen, H.M.; Lundgren, A.L. Watershed Management and Sustainable Development: Lessons Learned and Future Directions. Available online: http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_p013/rmrs_p013_037_043.pdf? (accessed on 23 March 2009).

- Independent Evaluation Department (IED). Post-Completion Sustainability of Asian Development Bank-Assisted Projects; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.; Meadows, D.; Randers, J. Limits to Growth—The 30 Year Update; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nellemann, C.; Corcoran, E. Dead Planet, Living Planet, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Restoration for Sustainable Development, A Rapid Response Assessment; United Nation Environment Programme (UNEP), Global and Regional Integrated Data (GRID): Arendal, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ukaga, O.; Maser, C. Evaluating Sustainable Development—Giving People a Voice in Their Destiny; Stylus Publishing LLC: Sterling, VA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, J.; van Soest, D.; Bulte, E. How sustainable is participatory watershed development in India? Agric. Econ. 2007, 36, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Rethinking watershed development in India: Strategy for the twenty first century. In Preparing for the Next Generation of Watershed Management Programmes and Projects; In Proceedings of the Asian Regional Workshop, Kathmandu, Nepal, 11–13 September 2003; Watershed Management and Sustainable Mountain Development Working Paper No. 5. Achouri, M., Tennyson, L., Upadhyay, K., White, R., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.D. Can Participatory Watershed Management be Sustained? Evidence from Southern India; Working Paper No. 22; South Asian Network for Development and Environmental Economics (SANDEE): Kathmandu, Nepal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, E.; Pagiola, S.; Reiche, C. The Costs and Benefits of Soil Conservation: The Farmers’ Viewpoint; World Bank Research Observer: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Palanisami, K.; Kumar, S.D. Leapfrogging the Watershed Mission: Building Capacities of Farmers, Professionals and Institutions. In Watershed Management Challenges: Improving Productivity, Resources and Livelihoods; Sharma, B.R., Samra, J.S., Scott, C.A., Wani, S.P., Eds.; International Water Management Institute: Columbo, Sri Lanka, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kondolf, G.M. Lessons learned from river restoration projects in California. Aquat. Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 1998, 8, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.R.; Clayton, S.R.; Alldredge, J.R.; Goodwin, P. Long Term Monitoring and Evaluation of the Lower Red River Meadow Restoration Project, Idaho, USA. Restor. Ecol. 2007, 15, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, A.; Gupta, S. CAPRI Technical Workshop on Watershed Management Institutions: A Summary Paper; CAPRI Working Paper No. 8; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, A. A long term post project evaluation of an urban stream restoration project (Baxter Creek, El Cerrito, California); Water Resources Center Archives, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge, D.A. A Guide for Desert and Dryland Restoration, New Hope for Arid Lands; Society for Ecological Restoration International: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, C.; Hulme, D. Basic Impact Assessment at Project Level. Available online: http://www.proveandimprove.org/documents/BasicImpact.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2010).

- Center for Global Development (CGD). When Will We Ever Learn? Improving Lives through Impact Evaluation; Report of the Evaluation Gap Working Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO). Preparing for the Next Generation of Watershed Management Programmes and Projects; In Proceedings of the Asian Regional Workshop, Kathmandu, Nepal, 11–13 September 2003; Watershed Management and Sustainable Mountain Development Working Paper No. 5. Achouri, M., Tennyson, L., Upadhyay, K., White, R., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2005.

- Brooks, K.N.; Eckman, K. Global Perspective of Watershed Management. Available online: http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_p013/rmrs_p013_011_020.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2016).

- Fenner, R.A.; Ainger, C.M.; Cruickshank, H.J.; Guthrie, P.M. Widening engineering horizons: Addressing the complexity of sustainable development. In Engineering Sustainability; Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) Publishing: London, UK, 2006; Volume 159, pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, M.E.; Schon, A. An Integrated Referential Framework for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the EASY ECO Evaluation of Sustainability EuroConference, Vienna, Austria, 23–25 May 2002.

- Schumacher, E.F. Small is Beautiful, Economics as if People Mattered; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Annis, S. Can Small scale Development be a Large scale Policy? The Case of Latin America. World Dev. 1987, 15, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). BRAC Annual Report; Abed, F.H., Ed.; BRAC: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Linn, J.F. Overview: pathways, drivers, and spaces. In Scaling-up in Agriculture, Rural Development, and Nutrition; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The New Generation of Watershed Management Programmes and Projects, FAO forestry paper 150; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Resources Institute (WRI). World Resources 2008: Roots of Resilience—Growing the Wealth of the Poor. In Collaboration with the United Nations Development Programme; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, D.; Erskine, P.D.; Parrotta, J.A. Restoration of degraded tropical forest landscapes. Science 2005, 310, 1628–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, S.; Howlett, M. Scaling-up of Policy Experiments and Pilots: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis and Lessons for the Water Sector. Water Resour. Manag. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT). Where the Land Is Greener, Case Studies and Analysis of Soil and Water Conservation Initiatives Worldwide; Liniger, H., Critchley, W., Eds.; World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT): Berne, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.D. Restoration Ecology to the Future: A Call for New Paradigm. Restor. Ecol. 2007, 15, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Lubchenco, J.; Melillo, J.M. Human Domination of Earth’s Ecosystems. Science 1997, 277, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frans, D.; Soussan, J. The Water and Poverty Initiative: What We Can Learn and What We Must Do; Water for All, Series 3; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scherr, S.J. Hunger, Poverty and Biodiversity in Developing Countries. Available online: http://ieham.org/html/docs/Hunger_Poverty_and_Biodiversity_in_Developing_Countries.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2009).

- Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R.; van Asselt, M.B.A. More Evolution than Revolution. Transit. Manag. Public Policy Foresight 2001, 3, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- World Watch Institute. State of the World 2008: Innovations for a Sustainable Economy; W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, C.; Tschinkel, H. Improving Watershed Management in Developing Countries: A Framework for Prioritising Sites and Practices; Overseas Development Institute, Agricultural Research and Extension Network: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Turkey National Watershed Management Strategy. Sector Note. Final Draft; World Bank, Europe and Central Asia Region, Sustainable Development Unit: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swallow, B.M.; Garrity, D.P.; van Noordwijk, M. The effects of scales, flows and filters on property rights and collective action in watershed management. Water Policy 2001, 3, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.W.; Morrison, K.E.; Bunch, M.J.; Venema, H.D. Ecohealth and Watersheds: Ecosystem Approaches to Re Integrate Water Resources Management with Health and Well Being; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gelt, J. Watershed Management: A Concept Evolving to Meet New Needs; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Global Environment Facility & Asian Development Bank (GEF-ADB). Integrated Ecosystem Management as an Alternative Approach for the People’s Republic of China: A Post Workshop Perspective. In Integrated Ecosystem Management, Proceedings of the International Workshop; China Forestry Publishing: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Coxhead, I.; Rola, A.; Kim, K. How do national markets and price policies affect land use at the forest margin? Evidence from the Philippines. Land Econ. 2001, 77, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, J. Stakeholder Power Analysis; International Institute for Environment & Development: London, UK, 2005; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Palanisami, K.; Suresh Kumar, D.; Wani, S.P. A Manual on Impact Assessment of Watersheds, Global Theme on Agro-Ecosystems Report No. 53; International Crops Research Institute for Semi-Arid Tropics: Andhra Pradesh, India, 2009; p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S. Institutional Analysis of Watersheds “With” and “Without” External Assistance in the Hills of Nepal. In Integrated Watershed Management: Studies and Experiences from Asia; Zoebisch, M., Mar Cho, K., Hein, S., Mowla, R., Eds.; Asian Institute of Technology (AIT): Bangkok, Thailand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, E. Six steps to successfully scale impact in the nonprofit sector. Eval. Exch. 2010, 15, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Menter, H.; Kaaria, S.; Johnson, N.; Ashby, J. Scaling-up, Chapter 1. In Scaling-up and Out: Achieving Widespread Impact through Agricultural Research; Pachico, D., Fujisaka, S., Eds.; International Center for Tropical Agriculture: Cali, Colombia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, R. Transcending scales of space and time in impact studies of climate and climate change on agrohydrological responses. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 82, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchione, T.J. Scaling-up, Scaling Down: Overcoming Malnutrition in Developing Countries; Overseas Publishers Association: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S. Scaling-up Community Driven Development: A Synthesis of Experience; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mansuri, G.; Rao, V. Evaluating Community Based and Community Driven Development: A Critical Review of the Evidence; World Bank Research Observer: Oxford, UK, 2003; Volume 19, pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves, J. Going to Scale: Can We Bring More Benefits to More People More Quickly? Available online: http://www.fao.org/docs/eims/upload/207909/gfar0086.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2013).

- McDonald, S.K.; Keesler, V.A.; Kauffman, N.J.; Schneider, B. Scaling-up Exemplary Interventions. Educ. Res. 2006, 35, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvin, P.; Jain, P.S.; Brown, L.D. Think large and act small: toward a new paradigm for NGO scaling-up. World Dev. 2000, 28, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, J.F.; Hartmann, A.; Kharas, H.; Kohl, R.; Massler, B. Scaling-up the Fight against Rural Poverty, An Institutional Review of IFAD’s Approach; Working paper 43; Global Economy & Development, Brookings Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Linn, J.F. Lessons on Scaling-up: Opportunities and Challenges for the Future. In Scaling-up in Agriculture, Rural Development, and Nutrition; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, M.; Jafry, R.; Marolla, M.; Phan, J. Scaling-up Community Efforts to Reach the MDGs—An Assessment of Experience from the Equator Prize. In The Millennium Development Goals and Conservation: Managing Nature’s Wealth for Society’s Health; Rose, D., Ed.; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2005; pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, A.; Linn, J.F. Scaling-up Framework and Lessons for Development Effectiveness from Literature and Practices; Wolfensohn Center for Development at Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, A.; Linn, J.F. Scaling-up: A Path to Effective Development; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ottoson, J.M. Knowledge for action theories in evaluation: Knowledge utilisation, diffusion, implementation, transfer, and translation. In Knowledge Utilisation, Diffusion, Implementation, Transfer, and Translation: Implications for Evaluation, New Directions for Evaluation; Ottoson, J.M., Hawe, P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 124, pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Workshop, in Strategies for Scaling out Impacts from Agricultural Systems Change: The Case of Forages and Livestock Production in Laos; Millar, J., Connell, J., Eds.; CGIAR: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 27, pp. 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Summerville, G.; Raley, B. Laying a Solid Foundation, Strategies for Effective Program Replication; Public/Private Ventures: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). Guidelines for Scaling-up. In Country Strategic Opportunities Programme (COSOP) Source Book; International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD): Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, R. Addressing institutional challenges to large-scale implementation. In Scaling-up in Agriculture, Rural Development, and Nutrition; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, N.; Bhattacharya, D.; Dimka, R.; Fanta, F.; Mangham-Jefferies, L.; Schellenberg, J.; Tamire-Woldemariam, A.; Walt, G.; Wickremasinghe, D. ‘Scaling-up is a craft not a science’: Catalysing Scale-up of health innovations in Ethiopia, India and Nigeria. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 121, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoker, G. Translating experiments into policy. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 2010, 628, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradach, J.L. Going to scale: the challenge of replicating social programs. Avalible online: http://ssir.org/images/articles/2003SP_feature_bradach.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2016).

- Wolfensohn, J.D. Foreword, Reducing Poverty on a Global Scale; Moreno-Dodson, B., Ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Scaling-up Health Service Delivery: From Pilot Innovations to Policies and Programmes; Simmons, R., Fajans, P., Ghiron, L., Eds.; WHO Library: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sania, N. The challenges of scaling-up. Lancet. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, N.F. Replicating Success: A Funder’s Perspective on the “Why” and “How” of Supporting the Local Office of an Expanding Organisation, A Case Study of Blue Ridge Foundation New York’s Support of the Taproot Foundation, NYC; Blue Ridge Foundation: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, A.; Linn, J.F. Scaling-up Through Aid: The Real Challenge; Global Views, No. 7; Brookings: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger-Mkhize, H.P.; de Regt, J.P. Moving Local- and Community-Driven Development from Boutique to Large Scale. In Scaling-up in Agriculture, Rural Development, and Nutrition; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.E.; Currie Alder, B. Scaling-up Natural Resource Management: Insights from Research in Latin America. Dev. Pract. 2006, 16, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Document of The World Bank for Official Use Only Report No: 28592. Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Loan in the Amount of US$20.0 Million and a Grant from the Global Environment Facility in the Amount of US$7.0 Million to the Republic of Turkey for the Anatolia Watershed Rehabilitation Project; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. The Self Deceiving State. IDS Bull. 1992, 23, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operations Evaluation Department (OED). Project Performance Assessment Report Eastern Anatolia Watershed Rehabilitation Project; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Implementation Completion Report (SCL-44770 IDA-32220 TF-25677 TF-51385) on a Loan in the Amount of US$100 Million and a Credit in the Amount of SDR 36.9 Million (US$50 Million Equivalent) to the People’s Republic of China for the Second Loess Plateau Watershed Rehabilitation Project. Available online: http://worldbank.mrooms.net/file.php/347/docs/LoessPlateau_ICR-2005.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2008).

- Nolan, S.; Unkovich, M.; Yuying, S.; Lingling, L.; Bellotti, W. Farming systems of the Loess Plateau, Gansu Province China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 124, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukkaya, I. Eastern Anatolia Watershed Rehabilitation Project, Implementation Period: 1993–2001, Powerpoint Presentation, Ankara, Turkey. 2002.

- Braun, A.R.; Hocdé, H. Farmer Participatory Research in Latin America: Four Cases. In Working with Farmers: The Key to Adoption of Forage Technologies; ACIAR Proceedings, No. 95; Stür, W.W., Horne, P.M., Hacker, J.B., Kerridge, P.C., Eds.; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 2000; pp. 32–53. [Google Scholar]

- Creech, H. Scale up and Replication for Social and Environmental Enterprises; The SEED Initiative and the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD): Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Ministry of Water Resources. Research on the Soil and Water Conservation and the Rural Sustainable Development in China; Development Research Center of the Ministry of Water Resources, China Watershed Management Project: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Grewel, S.S.; Dogra, A.S.; Jain, T.C. Poverty Alleviation and Resource Conservation through Integrated Watershed Management in a Fragile Foot Hill Ecosystem. In Proceedings of the 10th International Soil Conservation Organisation Meeting, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 24–29 May 1999.

- World Bank. World Development Report 2008, Agriculture for Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, J.; Cai, M. Watershed Development Best Practice Review, China Watershed Management Project; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, S.; Wani, S.P.; Rego, T.J.; Pardhasardhi, G. Knowledge Based Entry Points and Innovative up Scaling Strategy for Watershed Development Projects. Indian J. Dryland Agric. Res. Dev. 2007, 22, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sreedevi, T.K.; Shiferaw, B.; Wani, S.P. Adarsha Watershed in Kothapally Understanding the Drivers of Higher Impact: Global Theme on Agro Ecosystems Report No.10; International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics: Andhra Pradesh, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, L.M.; Sato, N.E.; McLaughlin, M.W.; Talbert, J.E. Theory Based Reform and Problems of Change: Contexts that Matter for Teachers’ Learning and Community; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, M.; Mitra, D.L. Theory based change and change based theory: Going deeper, going broader. Educ. Chang. 2001, 3, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, B.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S.; Skerrit, J. China’s Agricultural and Rural Development in the Early 21st Century; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, R.A.; Mushtaque, A.; Chowdhury, R.; Smith, G.B.; Ahmed, F. From One to Many: Scaling-up Health Programs in Low Income Countries; University Press Ltd: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Wyatt, J. Design Thinking for Social Innovation. Available online: https://www.ideo.com/images/uploads/thoughts/2010_SSIR_DesignThinking.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2016).

- Chen, L.; Wei, W.; Fu, B.; Lu, Y. Soil and water conservation on the Loess Plateau in China: Review and perspective. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2007, 31, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, H.; Brown, S. Scaling issues in watersheds assessments. In Proceedings of the Technical Workshop on Watershed Management Institutions, Managua, Nicaragua, 13–16 March 2000.

- Grameen Foundation. Available online: http://www.grameenfoundation.org/ (accessed on 25 September 2014).

- Buse, K.; Ludi, E.; Vigneri, M. Can project funded investments in rural development be scaled up? Lessons from the Millennium Villages Project. Nat. Resour. Perspect. 2008, 118, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, B.R.; Samra, J.S.; Scott, C.A.; Wani, S.P. Watershed Management Challenges Improving Productivity, Resources and Livelihoods; International Water Management Institute (IWMI): Battaramulla, Sri Lanka, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Christian-Smith, J.; Merenlender, A.M. The Disconnect between Restoration Goals and Practices: A Case study of Watershed Restoration in the Russian River Basin, California. Restor. Ecol. 2010, 18, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.; Filoso, S. Restoration of Ecosystem Services for Environmental Markets. Science 2009, 325, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, R.; Shiffman, J. Scaling-up Reproductive Health Service Innovations: A Conceptual Framework. 2002. In Proceedings of the Bellagio Conference: From Pilot Projects to Policies and Programs, Bellagio, Italy, 21 March–5 April 2003.

- Tennyson, R.; Wilde, L. The Guiding Hand; International Business Leaders Forum: London, UK; United Nations Staff College: London: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hiller, B.T.; Guthrie, P.M.; Jones, A.W. Overcoming Ex-Post Development Stagnation: Interventions with Continuity and Scaling in Mind. Sustainability 2016, 8, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020155

Hiller BT, Guthrie PM, Jones AW. Overcoming Ex-Post Development Stagnation: Interventions with Continuity and Scaling in Mind. Sustainability. 2016; 8(2):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020155

Chicago/Turabian StyleHiller, Bradley T., Peter M. Guthrie, and Aled W. Jones. 2016. "Overcoming Ex-Post Development Stagnation: Interventions with Continuity and Scaling in Mind" Sustainability 8, no. 2: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020155

APA StyleHiller, B. T., Guthrie, P. M., & Jones, A. W. (2016). Overcoming Ex-Post Development Stagnation: Interventions with Continuity and Scaling in Mind. Sustainability, 8(2), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020155