Abstract

This paper highlights the need for a more inclusive and sustainable development of social housing in rapidly developing countries of Asia, Latin America, and Africa. At the example of the Philippines, a multi-perspective development process for a bamboo-based building system is developed. Sustainability Assessment Criteria are defined through literature review, field observations and interviews with three stakeholder clusters: (1) Builders and users of traditional bamboo houses in the Philippines; (2) Stakeholders involved in using forest products for housing in other countries around the world; and (3) Stakeholders in the field of social housing in the Philippines. Through coding and sorting of data in a qualitative content analysis, 15 sustainability assessment criteria are identified clustered into the dimensions society, ecology, economy, governance, and technology. Guided by the sustainability criteria and four implementation strategies: (A) Research about and (B) Implementation of the building technology; (C) Participation and Capacity Building of Stakeholders; and (D) Sustainable Supply Chains, a strategic roadmap was created naming, in total, 28 action items. Through segmentation of the complex problem into these action items, the paper identifies one-dimensional methods leading to measurable, quantitative endpoints. In this way, qualitative stakeholder data is translated into quantitative methods, forming a pathway for a holistic assessment of the building technologies. A mid-point, multi-criteria, or pareto decision-making method comparing the 28 endpoints of the alternative to currently practiced conventional solutions is suggested as subject for further research. This framework paper is a contribution to how sustainable building practices can become more inclusive, incorporating the building stock of low-income dwellers. It bridges the gap between theoretical approach and practical applications of sustainability and underlines the strength of combining multi-dimensional development with stakeholder participation.

1. Introduction

This section introduces the case study of the paper. It is organized into (Section 1.1) Motivation, (Section 1.2) Research Objectives and Questions, and (Section 1.3) Limitations.

1.1. Motivation

Building practices around the globe are a major consumer of resources and energy, while producing significant emissions and waste [1]. Climate change and the environmental impact of construction make sustainable buildings an urgent requirement. Acknowledging this fact, the concept of sustainable building has spread widely [2]. In several countries, sustainable construction has already been institutionalized, such as in Switzerland through SIA 112/1 [3]. While the call for sustainable buildings is urgent, this holds true also, but not only, for advanced built environments. In rapidly developing urban centers in Asia-Pacific, the consideration of sustainability as design guideline is still limited to selected, advanced construction projects. Incorporating the building stock of low-income groups, has however received only little attention in research so far [2,4,5]. Tremendous urban poverty and urban growth rates in Latin America, Africa, and Asia-Pacific require a more inclusive and sustainable urban development [6]. Today, approximately 30 percent of the urban population in Asia-Pacific, which accounts for 570 Million people, lives in houses which are defined as inadequate by the United Nations [7]. Adequacy refers to a shelter providing safety and privacy, allowing healthy living as well as access to utilities, public services, and livelihood. The building stock of low-income groups is often characterized by substandard practices or temporary shelters, which can lead to fatal failures during earthquakes, typhoons, or floods [8,9]. Since the Philippines belong to the most affected countries by Climate Change around the globe [10,11], future extreme impacts are expected even more frequently, which causes vicious cycles of vulnerability for the urban poor. While adequate housing is a desire of most affected people, conventional building technologies, such as concrete and steel, as well as the systems to finance and obtain them, are mostly not adjusted to the affordability of low-income dwellers [12]. Collective efforts by governments, private sector, urban poor themselves and further relevant stakeholders is needed to provide low-income housing at scale and in a more socially-inclusive manner [13]. Solutions for more economic, disaster resistant and socially-inclusive housing are needed, which also provide more environmentally-friendly pathways for urban development. This paper addresses therefore the need for more sustainable housing solutions for low-income groups with the example of the Philippines.

The use of locally available raw materials is a potential to be explored in this regard. One material with interesting potential for the Philippines is the fast growing, widely spread bamboo. Since centuries, traditional bamboo housing can be found in the rural Philippines [14]. The use of bamboo in urban Philippines, however, is limited to informal settlements and non-load-bearing applications. For an application in cities, conventional concrete and steel are considered more modern, safe, and less maintenance intensive. Traditional bamboo construction has never undergone a strategic technical review to assess its adaptation potential to an urban and/or disaster prone context.

The contribution of this paper is to describe sustainability criteria and a pathway according to which bamboo-based construction needs to develop for contributing to the described need of adequate social housing in the Philippines. The roadmap presented in this paper provides the theoretic framework, which once implemented in actuality, will allow the use of Sustainability Assessments as a decision-tool as suggested in [15].

1.2. Research Objectives and Questions

The general objective of the paper is to develop a roadmap for transforming the potential bamboo raw material into a sustainable building technology suitable for social housing in the Philippines. This general objective is obtained through a set of specific objectives:

- To define meaningful, context-specific Sustainability Assessment Criteria for bamboo-based building technologies in social housing of the Philippines

- ➔

- What are requirements, barriers, and opportunities of stakeholders in social housing and for using bamboo as a construction material in this context?

- ➔

- Which pillars of sustainability are tackled through these requirements?

- ➔

- In which Sustainability Assessment Criteria can these requirements be translated?

- To define a Strategic Development Roadmap for the alternative building method, which transforms the theoretic criteria and requirements into implementable, measurable results

- ➔

- What are general strategies for implementing the theoretic context on the ground?

- ➔

- To which concrete action items lead the strategies for implementation and the Sustainability Criteria?

- ➔

- Through which methods can measurable results within these action items be generated?

1.3. Limitations

This section highlights the limitations of this research work:

- -

- The paper focuses on presenting Sustainability Assessment Criteria and Strategic Development Roadmap for developing a material potential into a sustainable building technology for social housing. Subject to further research are comprehensive test results about alternative building technology, and a multi-criteria ranking in comparison to conventional building methods. This introductory method paper does therefore not conclude with a recommendation for or against the alternative building technology.

- -

- The paper focuses on building technologies as an entry point for improvement in social housing. Aspects directly related to the value chain of the technology can be shaped or even controlled by technology providers and are therefore analyzed in the paper. However, an innovation in the construction sector does not likely change wider conceptual barriers on sustainable urban development and social housing [16]. An adjustment to such or, at best, influence of it can be achieved by long term multi-stakeholder dialogues and high-level advocacy. For a system change at scale, aspects such as land tenure, housing finance, governance, and policies in urban development, empowerment, and organization of informal communities, income generation for marginalized groups as well as basic services and infrastructure of settlements have to be addressed.

- -

- The paper uses the terminology of an urban context, since this is considered a more conservative boundary condition for the technology to be established on the market. ‘Urban’ relates to the compliance with urban policies and performance requirements. It does not exclude the technology from being applied in rural areas, in which a higher degree of regulatory freedom might exist.

2. Method

As introduced in the previous chapter, this paper looks at the need of Social Housing in the Philippines and analyses the potential of the alternative raw material bamboo for it. The method section is divided into two main sections: In 2.1 Definition of Sustainability Assessment Criteria, a theoretical context on requirements to be considered for the technology evaluation is provided. In 2.2 Strategic Development Roadmap, the pathway is shown how the raw material potential can be transformed into a building concept for social housing under consideration of the theoretical context. The roadmap specifies action items and defines methods for generating one-dimensional, quantitative data. Once implemented, the latter will allow a performance assessment of the alternative in all relevant dimensions individually. Since both steps are fundamentally connected to perspectives of stakeholders from various backgrounds, this process is named a Multi-Perspective Development Process (MPDP). It can be considered the first part of Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM). The latter is recognized and described as one possible concept for decision making in the field of sustainable development. It is widely recognized and applied in several disciplines, such as natural resource management [17], biofuel [18], farming [19], transportation [20], energy and reviews of energy sector applications [21,22], solid waste management [23] or public investment [24]. In [25], over 403 fuzzy MCDM techniques and applications published within two decades were comprehensively assessed and compared. Engineering was ranked the most common field of application. In the field of civil engineering, it was applied for building materials [26], housing related choices [27,28,29], or renovation choices [30]. Further, the inclusion of stakeholder perspectives was piloted in combination to using MCDM [31]. A majority of the product related studies cited above, compared technologies that are already established on the market and the focus is set on the ranking and decision-making through methodologies such as SAW, TOPSIS, or COPRAS [30]. In contrary to those studies, the case of this paper requires the development of a raw material into a technology first and foremost. The definition of sustainability assessment criteria and a roadmap for the development of the technology and data to assess it, was in the focus of the paper. Selected one-dimensional data results are provided in the results section, however, the paper calls for a comprehensive production and evaluation of all suggested data sets needed. Only the latter will enable comparing the alternative building method holistically to current conventional practices. While the ranking and decision-making of a MCDM is not part of this paper, it remains an objective for further research.

2.1. Definition of Sustainability Assessment Criteria

Literature reviews have shown that a mismatch between scope and actually obtained results can be observed when inappropriate sustainability assessment criteria are chosen. This can happen due to a supply, rather than a demand driven approach of using existing criteria [32]. To ensure a suitable selection of Sustainability Criteria, this research systematically involved stakeholder perspectives. In [33], the relevance of stakeholder involvement for environmental management has been analyzed according to disciplines and geographic context and various participatory methods were categorized. It is stated in [34] that a systematic approach for stakeholder engagement in the construction sector is a requirement for achieving overall sustainability. Also in other sectors, the involvement of stakeholders’ perspectives has been recognized as an important method for the definition of Sustainability Assessment Criteria [35]. In the Philippines, stakeholder involvement has been confirmed as a significant method for disaster risk reduction [36]. Especially in developing contexts where sustainability is the goal, enhanced mechanisms for participation throughout the lifecycle of planning and implementation are needed [37]. Depending on the respective perspective of stakeholders, different rankings are set in weighing Sustainability Criteria, but homogeneous stakeholders` preferences typologies can be identified in stakeholder sub-groups [38]. Therefore, not only the choice of the participatory method, but also the selection of stakeholder groups is critical. For the choice of stakeholders to be interviewed or involved, [15,34,39] distinguish two general approaches: a top-down or expert-driven approach and a bottom-up or stakeholder-driven approach. A combination of both reflects most recent scientific recommendations. It ensures the comprehensive capture of barriers and opportunities and enables participation and ownership throughout the layers of society that are affected by a case. With that, the gap between theory and implementation, as mentioned by [34] can be bridged. The expert and grassroots stakeholders for this research were identified through the context of the case being social housing in the Philippines and bamboo utilization for housing. Further, both national and international perspectives were captured, leading to the following three stakeholder clusters:

- (1)

- Builders and users of traditional bamboo houses,

- (2)

- Stakeholders involved in using forest products for housing in other parts of the world, and

- (3)

- Stakeholders in the field of social housing in the Philippines.

A detailed description of the samples in these stakeholder groups is described at the end of this the Section 2.1.

Stakeholder requirements are captured through cognitive interviews for which the interview principles for research and evaluation of [40] were followed. The interviews generated qualitative data on requirements, barriers and opportunities from multiple stakeholder perspectives. Depending on the background and context of the stakeholder group, either a less-formal/-structured Ethnographic Interview type, or an Interview Guide Approach was chosen. The ethnographic interviews provide high flexibility but nevertheless follow a specific, implicit research agenda. The interview guide approach provides more guidance on general themes that were to be captured by all stakeholder groups, and with that provide more comparability, but still allows flexibility to incorporate individual perspectives and requirements compared to standardized interviews, which follow exact wordings for every stakeholder [40]. The interview guides, listing general questions and themes that were developed for stakeholder groups are attached in Appendix. Special care was set on the formulation of the questions in the interview guide, following the principles of [40], being: simple, non-irritating, understandable in a cross-cultural context, bias-free, and open-ended. Probing questions were included in the interviews to verify viewpoints. Both descriptive or knowledge-based questions and interpretive or attitudinal questions were included. In addition to interview data, Field Inspections or Direct Observations were carried out over a period of four years. These were documented in written and pictured field reports, following the field observation guide for qualitative analysis provided in [40]. The field observations contain further ethnographic interviews as well as contextual information noted on the ground.

Barriers and opportunities, expressed by stakeholders or documented in field observations, were transformed in a qualitative Content Analysis to elicit most suitable sustainability criteria for the given case. The content analysis was done manually without the use of data management software. Common scientific guidelines for this process were applied: Through coding, sorting, and sifting, large quantities of qualitative information were reduced in volume in order to derive patterns:

- -

- As first level sorting, a barrier or opportunity was coded into one or several pillars of sustainability. This deductive approach bases on existing concepts of sustainability, where it is commonly accepted, that the nature of today’s global problems is complex and multi-dimensional [41]. Five dimensions were adopted for the given case: in line with most common definitions of sustainability [42], the pillars society, environment, and economy are denominated. Additionally, the relevance of governance is highlighted, especially in development cooperation [43]. Further, when dealing with products, such as in [23] or this case, the technical performance of products is added as an additional pillar.

- -

- As second level sorting, several sampling strategies, described in [44], were applied to identify common patterns in the qualitative data: (1) Group characteristic sampling, identifying patterns for several stakeholders in a group without neglecting their diversity, (2) Instrumental-use multi-case sampling, for generating actionable, useful findings, and (3) Comparison-focused sampling, for understanding similarities and differences between cases that can be compared to the present case.

- -

- As third level, Literature review and field observations, where available, were used to triangulate identified requirement patterns.

At the end of this process, raw data had been assembled and written-down in structured, narrative case studies. These narratives are presented in the results section.

In order to move from case studies on stakeholder groups to an analytical framework, the content analysis then derived Sustainability Criteria from the identified patterns. This part can be described as Analytic Induction, as it moves from existing concepts to generating a new, case-specific framework. Through Dichotomizing, or assigning symbols to a pattern, the stakeholder group patterns were translated to Sustainability Criteria:

- -

- When an issue was only expressed by one stakeholder or not expressed or noted at all within the stakeholder group or case, the respective criterion was left empty.

- -

- When an issue was expressed frequently among the stakeholder responses of a group, and it was further described:

- To act as driver, incentive or opportunity for a technology, the respective criterion was assigned with “+”.

- To act as barrier or hindrance for a technology, the respective criterion was assigned with “−”.

- To act in some perspectives as a barrier, in others as an opportunity for a technology, the respective criterion was assigned with “±”.

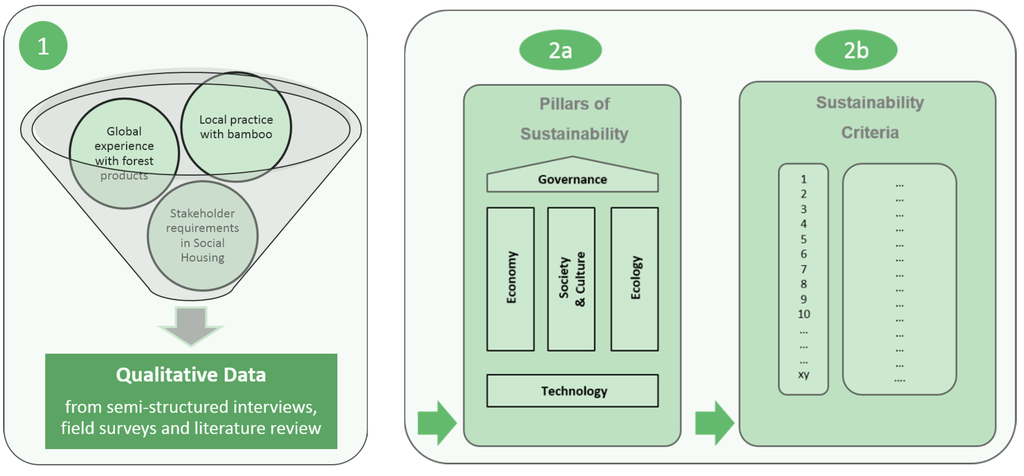

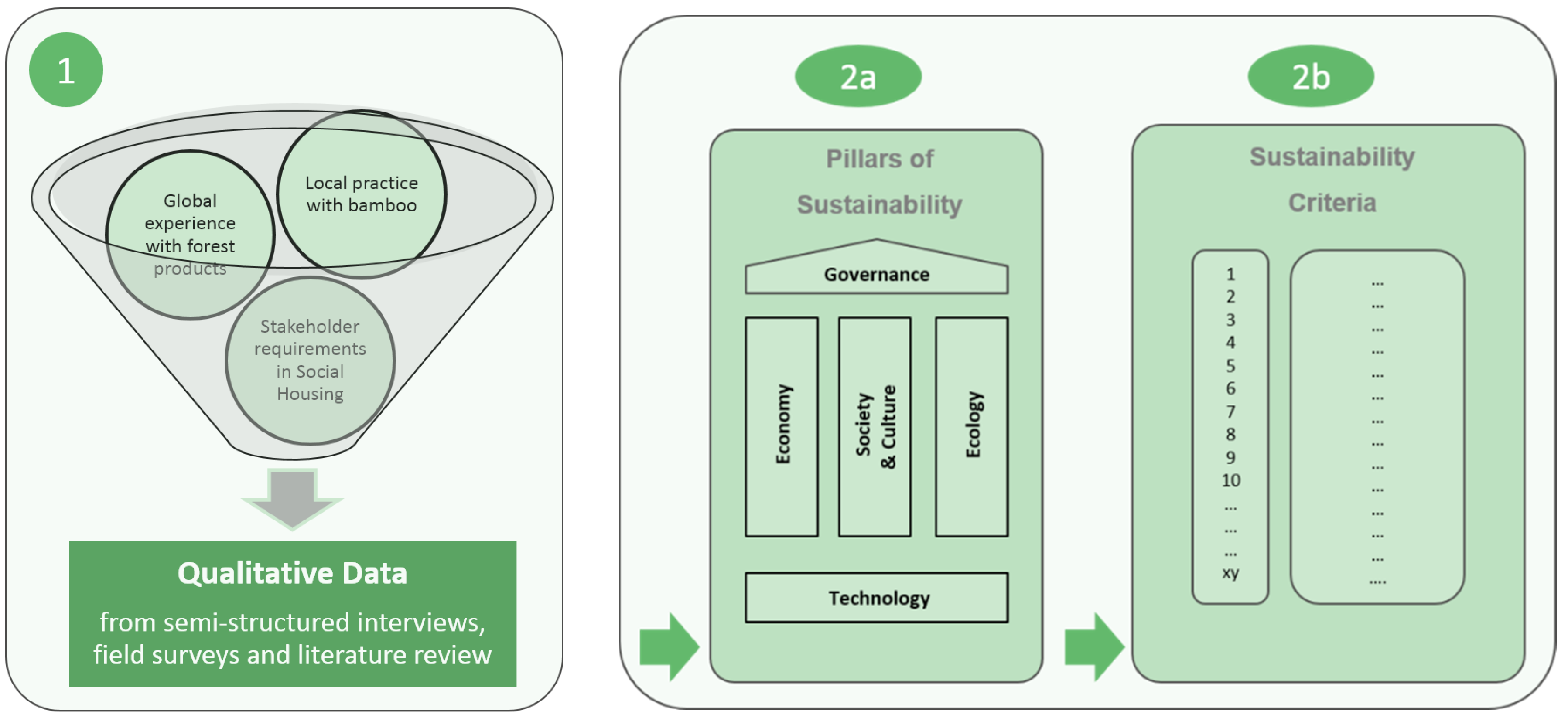

In Figure 1, we visualized how qualitative data is sorted and processed in a content analysis into sustainability criteria:

Figure 1.

Steps to obtain Sustainability Criteria from multi-perspective stakeholder data.

Figure 1.

Steps to obtain Sustainability Criteria from multi-perspective stakeholder data.

In addition to the method description above, a detailed explanation of the samples and interview guides for the stakeholder categories is described below:

- (1)

- Builders and users of traditional bamboo houses: Local bamboo construction practices were documented through field observation in selected areas of known bamboo tradition. Over a period of four years, from 2011 to 2015, a sample size of n = 16 field inspections were conducted as summarized in Table 1. A translator with local dialect was engaged where needed. The interview guide in Appendix, Table A1 was used to obtain data.

Table 1.

Sample description for field inspection of local bamboo practices.

| ID No. | Geography | Sample size (No. of Inspections, No. of Construction Practices Per Inspection) | Time Horizon for Inspections | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Island Group | Region | Provinces | |||

| 1A-1D | Visayas | Western Visayas | Iloilo, Capiz, Aklan, Negros | n = 4, > 10 | 2011–2015 |

| 1E-1F | Visayas | Negros | Dumaguete | n = 2, > 10 | 2014–2015 |

| 1G | Luzon | Cordillera | Abra | n = 1, > 10 | 2014 |

| 1H-1I | Luzon | Central | Tarlac, Pangasinan | n = 2, > 10 | 2014–2015 |

| 1J-1M | Luzon | Calabarzon | Laguna, Quezon | n = 4, > 10 | 2011–2015 |

| 1N-1O | Luzon | Bicol | Albay, Camarines Sur | n = 2, > 10 | 2013 |

| 1P | Mindanao | Davao | Davao | n = 1, > 10 | 2012 |

- (2)

- Stakeholders involved in using forest products for housing in other parts of the world: For identifying suitable cases for a cross-case pattern analysis, the criterion use of a load-bearing forest product for housing in urban areas was applied. Two cases were identified with significant findings on barriers and opportunities for the existing case. The co-authors brought-in relevant knowhow for each one of the cases (see author contributions). The chosen cases and their sample are stated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample description for international cases using forest products for housing.

| ID No. | Geography | Description | Sample Size (No. of Cases, Methods per Case) | Time Horizon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2A | Latin America | Bamboo-based construction | n = 1, field survey, expert review author 1 and 3, literature review | 2013 |

| 2B | European Union | Timber-based construction | n = 2, expert review by author 1 and 4, literature review | 2013–2014 |

For obtaining data, the interview and expert review guide in Appendix, Table A2 was used.

- (3)

- Stakeholders in the field of social housing in the Philippines: This stakeholder cluster is the most complex and manifold. For capturing the requirements of the cluster, five sub-stakeholder groups were identified through a systemic description of the conceptual framework of social housing in the Philippines by [45] as well as an analysis of the value chain of bamboo as building material by [46]. For each sub-group, n = 6 individuals were interviewed, resulting to a total of thirty interviews. All interviewed persons had an in-depth understanding of the Philippines, and have either a profession in the commercial or social housing field, or belong to a potential customer group. Half of the interviewees have followed pilot applications for modern bamboo housing over a certain period of time, while the other half had an external perspective. A gender mix between interviewees was considered. Below, the sub-groups are stated in Table 3, together with a description of the sample:

Table 3.

Sample description for social housing stakeholders in Philippines.

| ID No. | Geography | Description | Sample Size (Background, No. of Stakeholders) | Time Horizon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3A | Philippines | Low-income groups and their organizations, Housing clients | Grassroots leaders or individuals from four regions with highest housing need:

| 2013–2015 |

| 3B | Philippines and Regional | Policy makers and policy advocators such as international organizations |

| 2013–2015 |

| 3C | Philippines | Construction sector, housing, or service providers |

| 2013–2015 |

| 3D | Philippines | Technical professionals, Scientists |

| 2013–2015 |

| 3E | Philippines | Raw material suppliers |

| 2013–2015 |

2.2. Strategic Development Roadmap

Irrespective of manifold theoretical approaches towards sustainability, there remains a gap between theoretic, normative use of Sustainable Development as a Decision-Making strategy and practical applications [15,47]. The overall target of the wider research project, to which this introduction paper belongs, is a descriptive performance assessment comparing two actual technology solutions with each other. This requires a proven data base and implementation track record for both technologies- the currently applied, existing one and the alternative being currently only a theoretic material potential. Therefore, the core of this paper is the formulation of a Strategic Roadmap, which allows the development and implementation of the alternative construction technology. This paper links theoretic sustainability criteria to an implementable roadmap for action. As shown in [48] for several countries in Asia, it is deemed a crucial strength of sustainability indicator programs, when they are anchored in long-term implementation strategies.

From the qualitative data obtained through stakeholder consultations, four general Implementation Strategies were identified for creating data about the alternative building technology as seen in Table 4:

Table 4.

Implementation Strategies of the Technology Roadmap.

| No. | Implementation Strategy |

|---|---|

| 1 | Research about the building technology |

| 2 | Implementation of the building technology |

| 3 | Participation & Capacity Building of Stakeholders |

| 4 | Sustainable Supply Chains of raw material |

The core development consists of research about and implementation of the technology. The importance of developing a technology people-centered and along of client’s needs, as introduced earlier, is named critical by numerous literature references [13,34,37] and institutions such as [49]. For the application of a forest product based technology at larger scale, a specific requirement is further a sustainably generated, accessible supply of quality graded raw material. In [50] it is mentioned, that in many economies such a bamboo supply chain has to be built-up first.

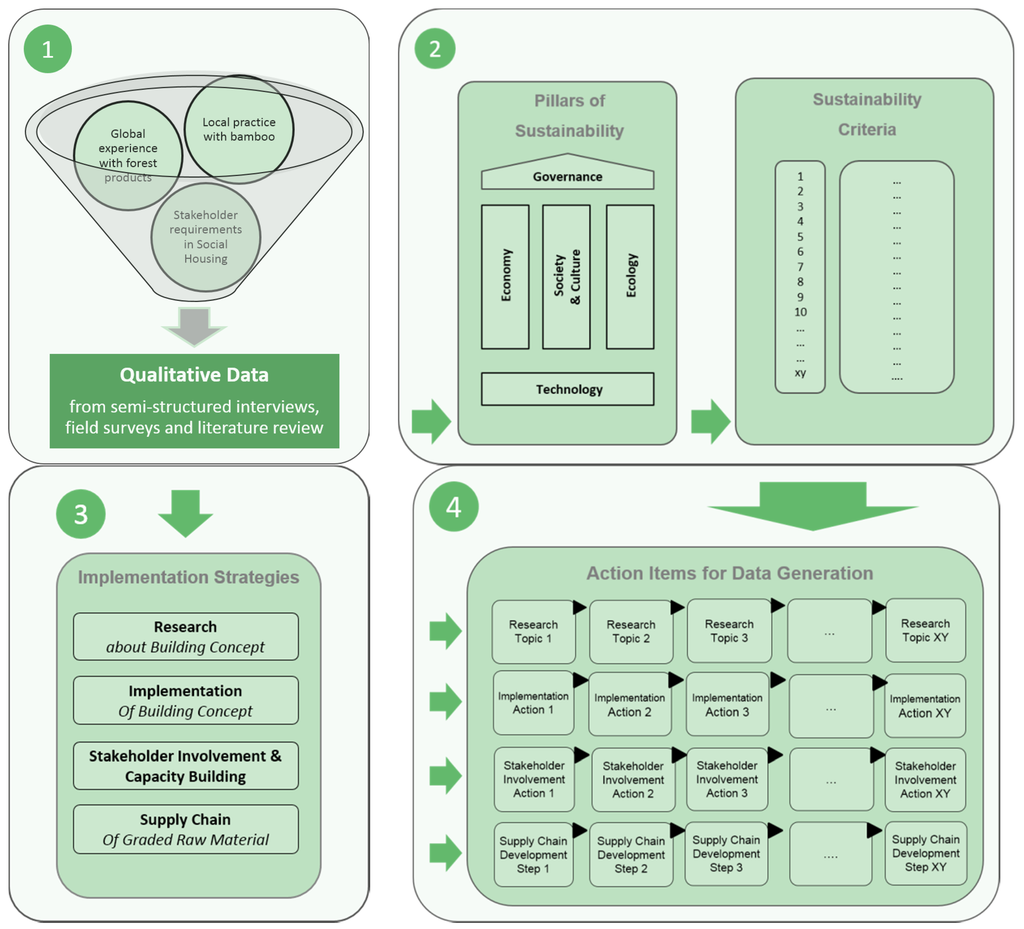

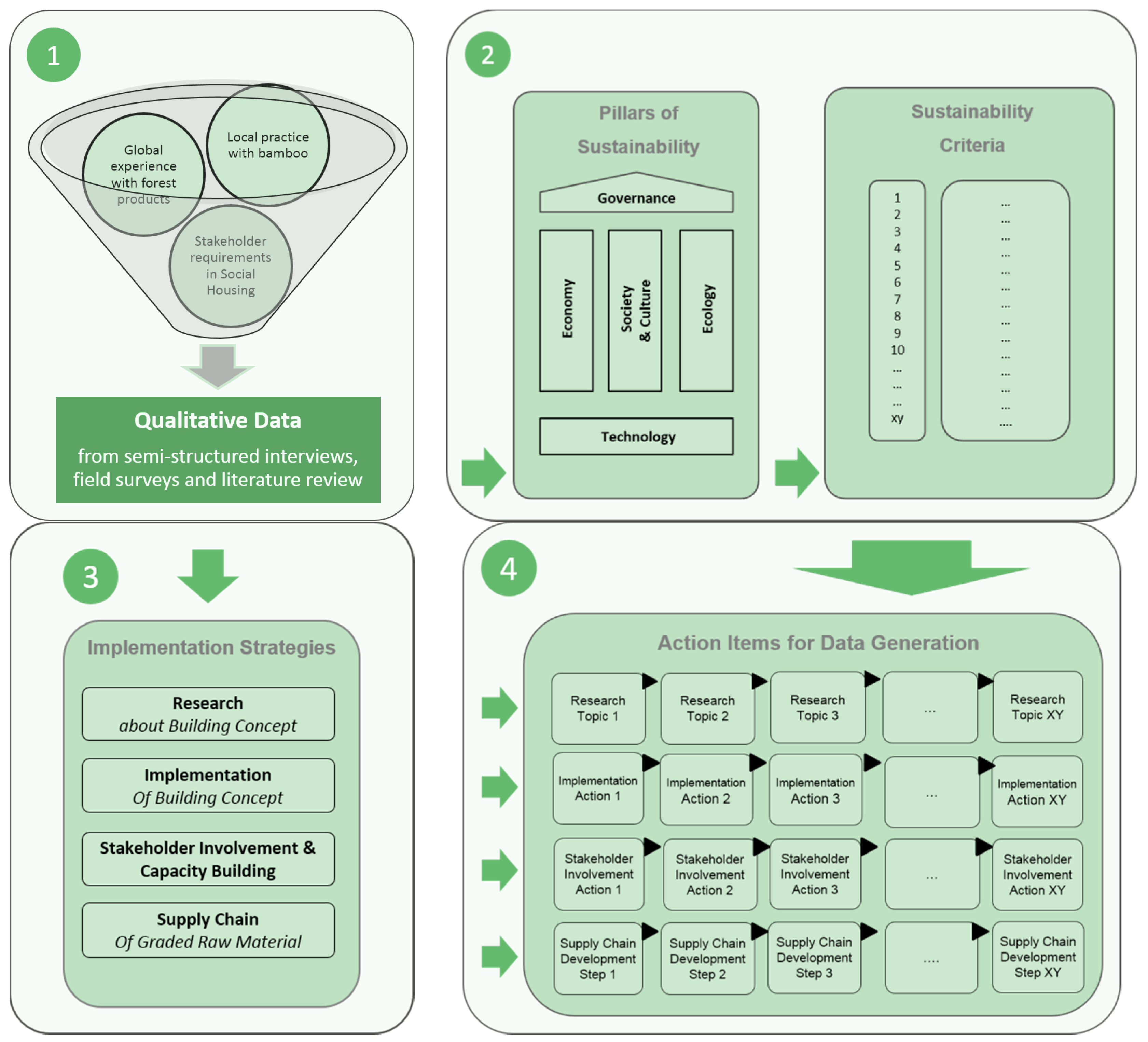

The four Implementation Strategies were then related to the Sustainability Criteria, to identify concrete and implementable action items. As a result, each implementation strategy contains action items across the pillars of sustainability. Figure 2 shows how criteria and implementation strategies are merged into a roadmap naming concrete action and the methods to obtain quantitative data per action:

The Implementation Strategies are recommended to be applied in parallel and iterations, in order to provide relevant feedback loops between each other: Outputs of the research agenda are translated into construction concepts. Through pilot applications barriers in realization are identified and additional research questions can be formulated. This approach of iterative action research acknowledges the importance of gradual system change developed over a period of time. Iterative processes contribute to awareness raising, ownership, and steps-wise change and are specifically suited for the introduction of alternative technologies with continuous stakeholder participation.

In order for action items to become measurable, a method for implementation has to be allocated. [32] identified that a systematic and transparent selection of the method is still subject to further research. Through segmentation of the complex problem Use of bamboo for social housing into action items, the paper is able to identify individual one-dimensional methods per action item leading to measurable endpoints. In this way, qualitative stakeholder data can be translated into quantitative methods for data generation. The choice of quantitative methods for data generation was determined by scientific quality and context related suitability. The combination of one-dimensional result into a mid-point, multi-criteria, or pareto result such as in [12,29,51,28] still remains a topic for further research. However, the pathway for a holistic assessment of the technologies is created.

Figure 2.

Steps to obtain a Strategic Technology Development Roadmap.

Figure 2.

Steps to obtain a Strategic Technology Development Roadmap.

3. Results

This section documents the identified Sustainability Assessment Criteria and the action items and methods within the Strategic Development Roadmap.

3.1. Sustainability Assessment Criteria

The Sustainability Assessment Criteria presented in this chapter are derived from qualitative data about local practices, knowledge exchange through assessing bamboo construction in Latin America and timber frame construction in Europe, as well as requirements expressed by multi-perspective stakeholder groups in the pilot country. Themes of questions are documented in Appendix, while flexibility was provided to deepen the interviews according to specific interviewee concerns. Results are presented in each of the categories, before the summary of all criteria are stated.

3.1.1. Findings about Local Practices in Rural Areas of the Pilot Country

Sixteen field inspections and several transcripts of conversations with bamboo builders and users per field inspection have been analyzed following the nine themes of questions documented in Table A1. Mentioned requirements were coded into pillars of sustainability and sorted into the eight sustainability criteria stated in Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Sustainability Criteria elicited from local practices with bamboo.

Figure 3.

Sustainability Criteria elicited from local practices with bamboo.

| SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT CRITERIA | |||||||

| No. | Pillar of Sustainability | Criteria | (1) | ||||

| Society | Technology | Economy | Ecology | Governance | |||

| 1 | Social acceptance & advocacy | − | |||||

| 2 | Participation & identification | ||||||

| 3 | Capacity building | − | |||||

| 4 | Income at local value chain | + | |||||

| 5 | Maintenance & incremental development | − | |||||

| 6 | Health & comfort | + | |||||

| 7 | Enduring safety & performance | − | |||||

| 8 | Standardization, quality control, pace | - | |||||

| 9 | Continuous innovation | ||||||

| 10 | Cost advantage of houses | + | |||||

| 11 | Scalable business model | ||||||

| 12 | Supply accessibility | + | |||||

| 13 | Supply availability & sustainability | ||||||

| 14 | Environmental impact | ||||||

| 15 | Compliance to policies & regulations | ||||||

The below narrative case description describes the findings in detail:

- -

- As per today, buildings using bamboo are based on traditional practices and designs relying on orally transferred skills of local builders. However, a change in building practice was noticed towards conventional technologies. This causes lesser builders to transfer their skills to next generations, which makes bamboo construction less likely an additional source of income. The latter is critical, since only few inhabitants have skills in maintaining a raw material sourced from the countryside. The development of skills and livelihood opportunities through bamboo craftsmanship were highlighted to be relevant criteria expressed during the field study with the rural population and local builders.

- -

- The field study extracted that conventional concrete and steel houses are considered more modern, safer, and less maintenance intensive. The social acceptance of a building method is also largely connected to a contemporary house design. Statistics and survey have shown that the highest share of today’s bamboo users belong to low-income groups who experience shortcomings tapping into more commercial options. The utilization of the material is therefore perceived equivalent to being poor.

- -

- Interviews with inhabitants reveal that a comfortable living climate is a frequently mentioned positive aspect. This said, it is noted, that the definition of “comfort” in the tropical climate of the Philippines has to be classified context specific.

- -

- Statistical information of the Philippine Government revealed that inhabitants living in the traditional lightweight bamboo houses are not ensured of basic safety during natural disasters, especially typhoons [8]. Next to interviews with Government experts, the correlation between vulnerability and bamboo housing has been documented in several post-disaster damage assessment reports after typhoon Haiyan in 2013. Among others, this can be ascribed to temporary connections between the bamboo elements, which not maintained, often underutilize the potential of the raw material as fail as weakest component of the system. As a result, the preferences of people towards conventional technologies, which are considered as more safe, gain further speed. An improved technical performance of bamboo-based houses in compliance with technical minimum standards for disaster resistance is considered as Sustainability Assessment Criterion.

- -

- The abundant availability of bamboo made it ever since an affordable raw material for construction across the archipelago. Cost savings compared to conventional solutions were named a key incentive for using the material.

- -

- Bamboo houses are mostly found in rural communities living nearby bamboo sources, where its craftsmanship provides a valuable source of income next to farming. Since every builder uses bamboo only for a few houses, no shortcomings of supply were noticed.

In summary, the field survey and expert interviews reveal that none-standardized bamboo houses are mainly used because of economic aspects. However, they have never undergone a technical development responding to the requirements of a more urban and disaster prone context. As a result, the potential to apply bamboo as load bearing material for house construction in the urban Philippines remains untapped until a building concept can respond to comply with technical and social requirements.

3.1.2. Findings from Case Studies Using Forest Products for Housing around the Globe

Case studies from other regions provided qualitative data on barriers and opportunities to use forest products for housing. Two selected cases have been studied: (A) Bamboo construction in Latin America and (B) Timber frame construction in Europe. The coded and sorted data led to seven criteria from case (A) and 11 criteria from case (B), which partially overlapped with one exception. In total 12 criteria were elicited, as shown below in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Sustainability Criteria elicited from global case studies of using forest products.

Figure 4.

Sustainability Criteria elicited from global case studies of using forest products.

| SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT CRITERIA | ||||||||

| No. | Pillar of Sustainability | Criteria | Case | |||||

| Society | Technology | Economy | Ecology | Governance | (2A) | (2B) | ||

| 1 | Social acceptance & advocacy | ± | + | |||||

| 2 | Participation & identification | |||||||

| 3 | Capacity building | + | + | |||||

| 4 | Income at local value chain | |||||||

| 5 | Maintenance & incremental development | |||||||

| 6 | Health & comfort | + | ||||||

| 7 | Enduring safety & performance | + | + | |||||

| 8 | Standardization, quality control, pace | + | ||||||

| 9 | Continuous innovation | + | + | |||||

| 10 | Cost advantage of houses | + | ||||||

| 11 | Scalable business model | + | ||||||

| 12 | Supply accessibility | + | ||||||

| 13 | Supply availability & sustainability | + | + | |||||

| 14 | Environmental impact | + | ||||||

| 15 | Compliance to policies & regulations | + | + | |||||

Six of the eight criteria, extracted from the data about Philippines bamboo utilization, can also be found in the two global cases. The below narrative description is a cross-pattern analysis describing the findings in detail:

- (A)

- Bamboo construction in Latin America:

- -

- In several countries of Latin America, the indigenous population used to live in houses made from bamboo. During the colonial time, European technologies started to influence traditional practices. This was the beginning of the construction technique locally named “Bahareque”: a combination of the original bamboo frame system with cement plaster cladding and an evolvement of skill and capacity. Bahareque spread as success story in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru as a confluence of traditional and new materials and practices. Especially the Coffee Belt Region of Colombia substantial parts of the houses, up to 50 percent, have been built with this construction method in the past 200 years. Similarly to the Asian case, this development was motivated by the high availability of bamboo.

- -

- Further, empiric evidence showed its good response to earthquakes compared to the non-reinforced adobe systems utilized in the area during those days. Due to a high seismic activity in the Colombian Coffee Belt, the system was tested during several seismic shocks. An earthquake with strongly destructive impact took place in 1999. The event of magnitude 6.2 on Richter scale had a shallow depth of 6 km and an epicenter of only 20 km away from major cities, leading to the death of more than 1600 people. Despite the destructive power of the natural disaster, it was remarkable that more than 90 percent of the causalities occurred in non-bamboo structures. Post-impact studies showed that the causalities in or near bamboo houses occurred only due to deterioration of the structural elements or debris from heavy materials destroying the lighter bamboo structures. Therefore, the Association of Structural Engineers in Colombia (AIS) started to study the characteristic behavior of the construction method.

- -

- The idea to standardize and develop a building code for capturing the design rules of this construction type arose, which lead again to several improvements of the construction method. From the year 2000 onwards, tests were carried out in Colombia on the mechanical properties of the local bamboo, called Guadua Angustifolia, according to a preliminary draft of ISO 22157, which was published four years later under the name Bamboo—Determination of physical and mechanical properties [52,53]. Further tests were conducted on frame wall systems and on full-scale buildings to determine its resistance to seismic impacts. The results of these investigations were the basis for the building code, which was published in 2002 and is known today as Colombian Building Code- Section E: Design and Construction of Houses of one and two stories with plastered Bahareque [54].

- -

- The remarkable technical development, which took place in Latin America, contributed to several extraordinary, globally rewarded structures such as in [55], which changed the paradigm from a material for the poor to an ecologically valued, high performance material for wealthy customers.

- -

- While this is a considerable track record, the Colombian development has not entered into a large scale application of the building concept, despite the existence of research and regulations. Structures are however implemented on a project basis, and no institutions exist providing affordable construction and after sales services for a large number of cost-efficient houses. Only a few recent social housing projects exist, where it was noted during the field study in Colombia, that the needs and requirements of civil society customers have hardly been considered in the design. A lack of ownership and identification of inhabitants in social housing projects was identified.

- -

- As second main barrier for Latin American bamboo construction to scale are the regulatory barriers in supplying bamboo. Being declared as forest product, special permits are required despite its availability.

The case of Asia has analogies to the Latin American history and is yet to be looked at regionally and country specific. While bamboo is also an available raw material in many countries of the Asia-Pacific, its utilization in round shape has hardly evolved. In countries like China and Vietnam, the bamboo serves mainly as raw material for industrially produced laminated products [50]. Target markets are pre-dominantly for Western or higher income local customers. In the Philippines, same as with other countries in Asia, the need for urban housing was never combined with the potential of using the local raw material. While the existing local practice was not responding to the needs of urban stakeholders for housing, there was hardly any scientific technical development taking place or, if so, it was not connected to application projects. In Latin America, the strong disaster performance during earthquake impacts has boosted its acceptance among civil society. Since the Philippines encounter earthquakes and typhoons, the technology has to perform against multi-hazards reliably. Lastly, the cases from Latin America highlight that, excluding luxury resorts, a lacking ownership and identity of lower income groups towards living in bamboo-based houses is a bottleneck. The relevance of participation and involvement is highlighted as a criterion for market acceptance and the active stake of low-income groups is a crucial criterion. A technical transfer and South-South sharing of experiences was found to considerably speed-up the Asian development by bringing in technical knowhow in complementation to the conceptual framework of Asia.

- (B)

- Timber frame construction in Europe

As a second case study, the development of timber frame construction systems in Europe was assessed.

- -

- In Europe, wood is increasingly used in housing, schools, administrative, cultural, and exhibition buildings, halls and factories, as well as in bridges, sound barriers, hydraulic engineering and avalanche control. Its social acceptance varies per country in the EU, but several examples exist where the population adopted it as modern building material with a major share of built environment.

- -

- One driver for this development is a growing market of stakeholders emphasizing ecological concerns. Timber structures are related with CO2 sequestration, being a renewable raw material, producing little construction waste, and requiring low energy for processing. In South Europe, the use of wood is becoming synonym of energy efficient building.

- -

- Moreover, the highest levels of indoor comfort can be obtained with timber structures, which however requires a combination with further building materials.

- -

- Timber engineering is commonly lectured in academe education, which reduces barriers of professionals to train capacity and apply the building material later on.

- -

- The flexibility of lightweight modular timber construction is particularly suited because of its adaptability and pace in construction. Driver for continuous innovation are industrial business models reducing cost per square meter. Industrialized manufacturing methods on a high prefabrication level have significantly advanced building with wood and opened markets for the sector, especially on an urban scale.

- -

- Several European governments are currently deploying programs on building with wood. Two additional building applications are identified as potential markets: multi-story large volume new buildings, as well as retrofitting using timber based solutions. Both have been successfully realized and are now on the way to up scaling, in Europe.

- -

- In order for innovative wood-based building methods to be approved on the European market, the European Technical Approval scheme has to be considered [56]. For decades, the fire resistance resulted in a barrier of timber construction for multi-story buildings [57], while once technically solved, it opened the market for more applications. Compliance with rules and regulations, ensuring a durable technical performance, is however a must for an application in the EU.

- -

- However, building with wood sector faces a growing intrusive environment of legal frameworks, critical public perception as well as a rising economical threat which is becoming a barrier to a successful future economic development of the wood industry.

- -

- Supply availability & sustainability: regional scale, approval schemes.

3.1.3. Learnings from Stakeholder Requirements in Social Housing of the Philippines

In 30 semi-structured interviews, clustered into five stakeholder-sub-groups, requirements in Philippine social housing in general and implementing the alternative building technology specifically were captured. Obtained barriers and opportunities were sorted, condensed, and clustered. The evaluation has returned the most comprehensive set of criteria. While common themes from the other cases were found, also one critical criterion was added: participation & identification. The comprehensiveness of criteria displays the complexity of social housing. Below, in Figure 5, all identified criteria are summarized:

Figure 5.

Sustainability Criteria elicited from stakeholders involved in social housing.

Figure 5.

Sustainability Criteria elicited from stakeholders involved in social housing.

| SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT CRITERIA | |||||||

| No. | Pillar of Sustainability | Criteria | (3) | ||||

| Society | Technology | Economy | Ecology | Governance | |||

| 1 | Social acceptance & advocacy | + | |||||

| 2 | Participation & identification | + | |||||

| 3 | Capacity building | + | |||||

| 4 | Income at local value chain | + | |||||

| 5 | Maintenance & incremental development | + | |||||

| 6 | Health & comfort | + | |||||

| 7 | Enduring safety & performance | + | |||||

| 8 | Standardization, quality control, pace | + | |||||

| 9 | Continuous innovation | + | |||||

| 10 | Cost advantage of houses | + | |||||

| 11 | Scalable business model | + | |||||

| 12 | Supply accessibility | + | |||||

| 13 | Supply availability & sustainability | + | |||||

| 14 | Environmental impact | + | |||||

| 15 | Compliance to policies & regulations | + | |||||

The below narrative case description describes the findings in detail:

- -

- Lower initial construction costs were mentioned as major incentive to consider alternative building methods across all stakeholder groups, since latter will allow more people to access adequate housing. Economic advantages are therefore an important entry point for system change, however, not the only requirement for an innovation to succeed on the social housing market.

- -

- Facilitating regulations and a legal approval of the building technology on national or even regional or global scale are needed for a technology spread. Since, however, the alternative building technology is not covered by existing building codes, but restricted by general requirement in force; compliance to such and design rules for it have to be developed. Little enforcement of minimum structural performance requirements in social housing make substandard practices likely and might slow down the spread of a performing technology.

- -

- Showcasing the technology at full scale, for example through demonstration units, as well as national, regional, and global best practice sharing and advocacy, have been mentioned to be needed for assessing customer acceptance. Customer acceptance and first positive sales results are promising from the current start-up operations in the Philippines. It is acknowledged, though, that this acceptance is driven to large parts by the urgency of an underserved market and the need for more adequate housing, which the technology provides a good solution for.

- -

- The interviews revealed that the value chain is an important criterion, which can create local impact from cradle-to-grave: from resource planting up to the demolition of houses built with it. Relevant barriers and risks for an application at scale, though, are also caused by this value chain. Existing bamboo supply chains have to be adjusted and scaled according to the needs of the technology.

- -

- Critically mentioned were further the material availability and long term sustainability of bamboo supply, which will influence the pace and dimension of a technology scale-up. Both, market-prices for bamboo and quality grading have to be established for affordable, performing construction. Training on sustainable harvesting of bamboo has to fall in line with a logistic concept for accessing the resources and bringing it to the processing sites. It is predicted that increasing harvesting yield and efficiency is a time intensive process. Involvement and strengthening networks of existing bamboo suppliers is deemed important for immediate supply. It was mentioned as an asset, that the value chain can create rural-urban linkages combining two governmental targets: Rural farmers receiving livelihood opportunities through material supply and urban poor being clients for housing. The factors pace of scale-up and absolute scale intended are crucial for a strategy definition. The ecological impact reduction through utilization of renewable, available raw materials creates policy incentives for the government, which can mobilize multi-stakeholder involvement for the needed supply and construction related capacity building. The environmental impact has to be proven transparently.

- -

- Cross-cutting through all six stakeholder clusters is the trajectory of capacity building: continuous skills development for stable minimum quality insurance is a requirement, both in supply as well as construction. This is a sensitive process, where local practices and learnings from global sharing have to be merged culturally sensitive. It involves all levels of stakeholders, from low-skilled to skilled workers and academe.

- -

- The interviewed stakeholders highlighted that investing into a residential home is a long term commitment for most people. A new building practice causes customers and loan providers to hesitate taking the risk. Due to the disaster prone context of the Philippines, a reliable technical performance ensuring people’s safety has been mentioned as important. A comprehensive technical development is the basis for such a reliability and durability enabling trust. As seen in the case of Colombia, a convincing system performance will create a track record for the technology. During interviews with stakeholders involved in the technology development, this knowledge has resulted in solid trust into the technology. The South-South sharing has increased speed of gaining such a knowledge basis. Besides disaster resistance, stakeholders from low-income groups expressed their strong desire to obtain durable houses causing little maintenance efforts. To be highlighted is also the relevance of a strong quality control concept ensuring a stable technical performance in implementation projects.

- -

- A continuous process of optimization and innovation in prefabrication and construction will increase the speed of construction, decrease the level of skills needed, and strengthen the scalability of the approach.

- -

- It was underlined both by potential clients and facilitators, that incremental expansion and upgrading along with societal development is common reality and should be enabled.

- -

- Inclusion of low income groups is a pathway to success, since conventional modes of house provision are mostly not affordable and do not consider the factor of ownership. The participatory process gives consideration to the concerns of clients in planning, construction and post-occupation.

3.1.4. Sustainability Assessment Criteria

In summary, 15 partially interlinked Sustainability Assessment Criteria were derived from the findings through literature review, field survey and interviews with the three fields: (1) Builders and users of traditional bamboo houses, (2A) Stakeholders using bamboo for housing in Latin America or (2B) timber for housing in Europe, and (3) Stakeholders in the field of social housing in the Philippines. Figure 6 below summarizes all mentioned requirements, using the symbol allocation process described in the Method section.

Figure 6.

Summary of Sustainability Assessment Criteria.

Figure 6.

Summary of Sustainability Assessment Criteria.

| SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT CRITERIA | ||||||||||

| No. | Pillar of Sustainability | Criteria | Case | |||||||

| Society | Technology | Economy | Ecology | Governance | (1) | (2A) | (2B) | (3) | ||

| 1 | Social acceptance & advocacy | - | ± | + | + | |||||

| 2 | Participation & identification | + | ||||||||

| 3 | Capacity building | - | + | + | + | |||||

| 4 | Income at local value chain | + | + | |||||||

| 5 | Maintenance & incremental development | - | + | |||||||

| 6 | Health & comfort | + | + | + | ||||||

| 7 | Enduring safety & performance | - | + | + | + | |||||

| 8 | Standardization, quality control, pace | - | + | + | ||||||

| 9 | Continuous innovation | + | + | + | ||||||

| 10 | Cost advantage of houses | + | + | + | ||||||

| 11 | Scalable business model | + | + | |||||||

| 12 | Supply accessibility | + | + | + | ||||||

| 13 | Supply availability & sustainability | + | + | + | ||||||

| 14 | Environmental impact | + | + | |||||||

| 15 | Compliance to policies & regulations | + | + | + | ||||||

The stated Sustainability Assessment Criteria are multi-dimensional covering the pillars society, economy, ecology, technology, and governance. The stakeholder interviews in the field of social housing have resulted in the most comprehensive set of criteria, while the stakeholder assessment (1), (2a), and (2b) have underpinned specific sub-sets of it.

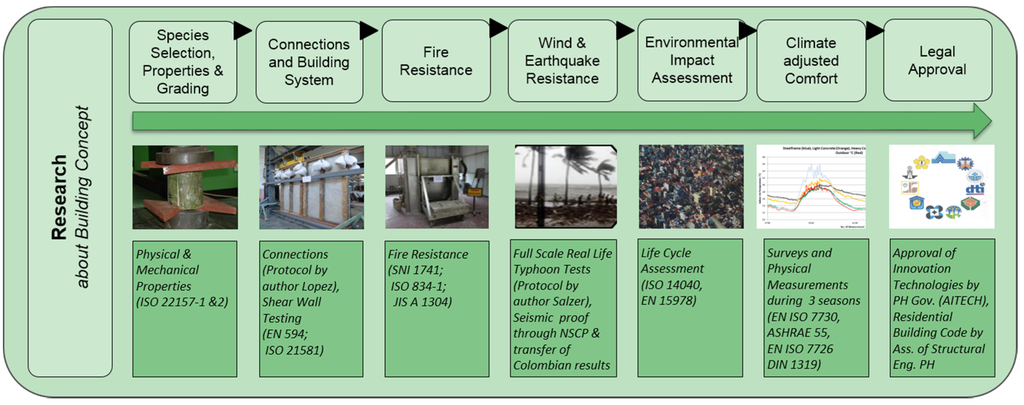

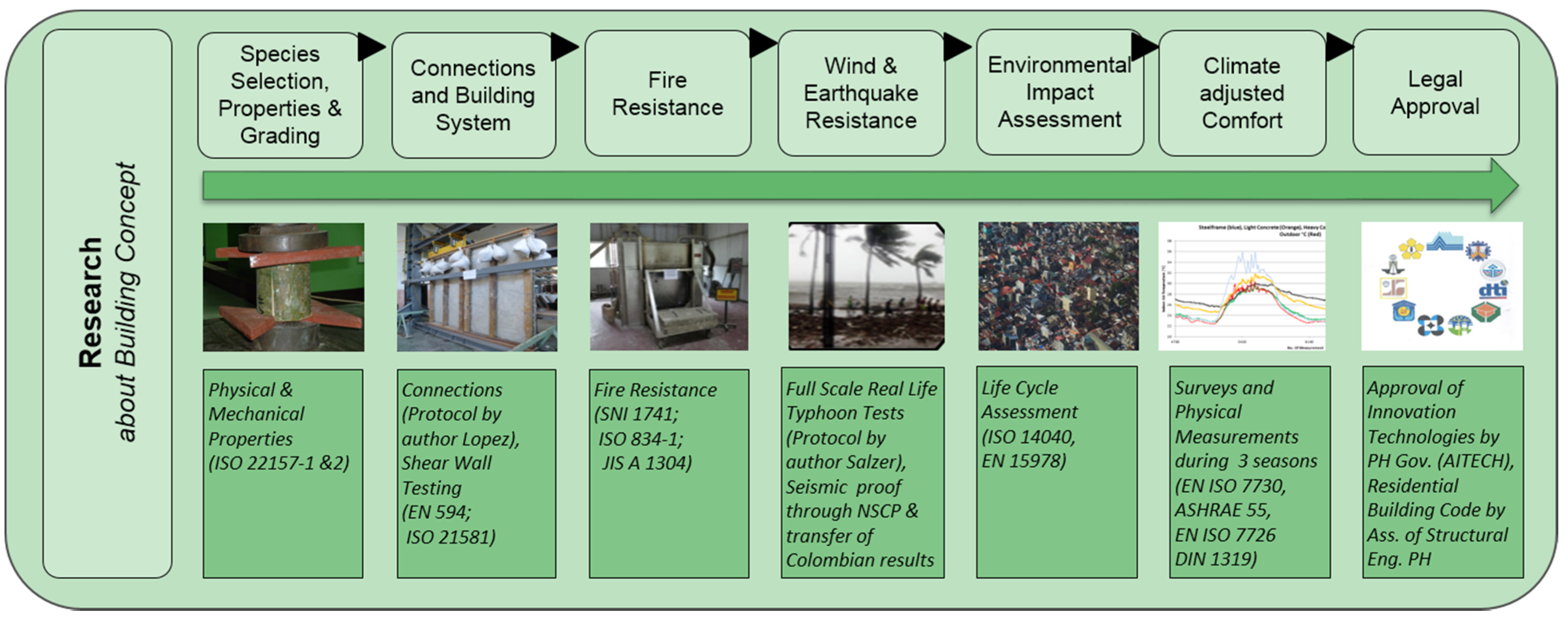

3.2. Strategic Technology Development Roadmap

This section documents the roadmap which, once implemented, will enabling a Holistic Performance Assessment in a Multi-Criteria Development Process. Within the four implementation strategies, (1) Research about -, and (2) Implementation of the building technology, (3) Participation & Capacity Building and (4) Sustainable Supply Chain, 28 action items for data generation were identified. The methods for data generation in these 28 action items were specified according to scientific requirements and context related suitability. The sum of all action items covers a cradle to grave life cycle of the product: whether within a respective action item, such as Life Cycle Assessment quantifying environmental performance, or whether through the consecutive alignment of various action items after each other, such as supply, followed by construction, use phase of the house and its end of life. The methods suggested for data generated in the individual endpoints will provide transparency on individual aspects of sustainability. In the following, the 28 action items are presented alongside of the methods for data generation:

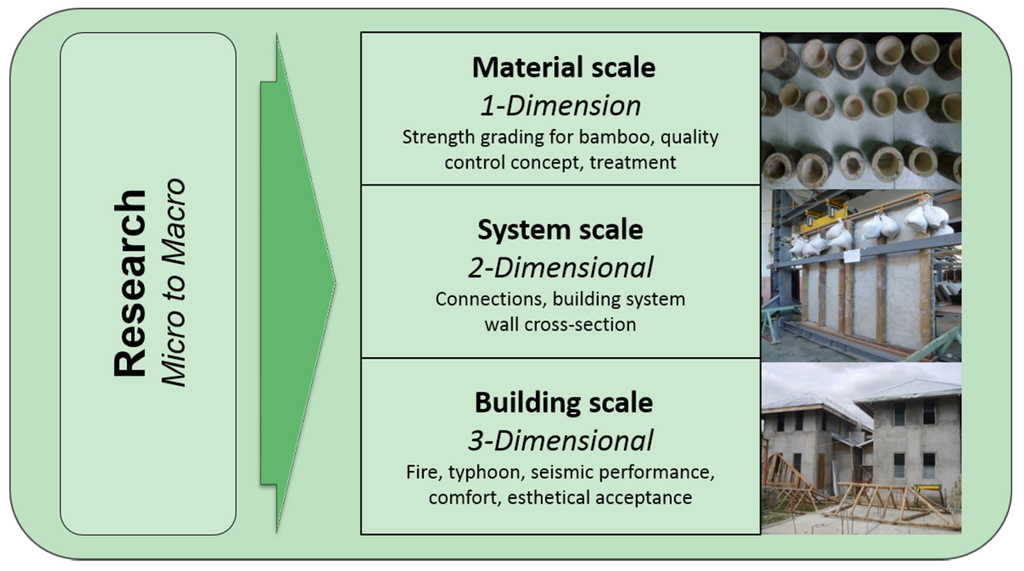

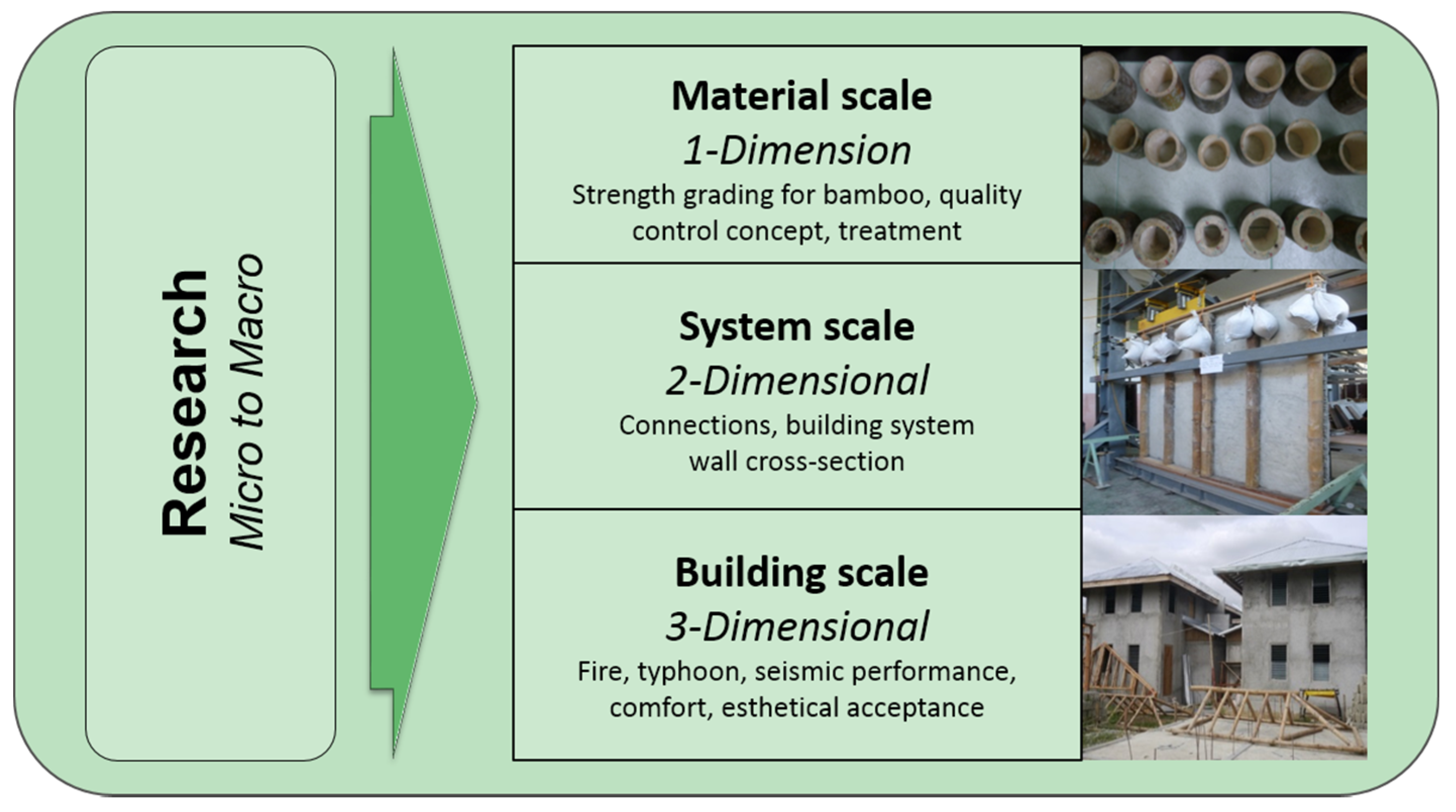

- (1)

- The Research Strategy was segmented in research topics on material, system, and building scales, as visualized in Figure 7. Data generated in these three dimensions enables to understand and control the technical performance, and with that contribute to social acceptance through compliance with urban policies. The action items cover all pillars of sustainability and are summarized in Figure 8. For a sustainable urban development, the complex settlement scale would also require consideration. Latter is however hardly tied to a specific construction method and is therefore not part of this technology-related roadmap.

Figure 7.

Comprehensive research from Material, over System, to Building Scale.

Figure 7.

Comprehensive research from Material, over System, to Building Scale.

Material-Scale: Research contains selection and strength grading of bamboo species, which ensures Technical Performance, Cost Advantage, and Sustainable Supply. Through field and literature study potential species can be identified. Similar to the field of timber engineering, a strength grading of bamboo culms has been carried out to understand the material characteristics and possible methods of utilization. Since no international standard on bamboo strength grading exists, the authors define biologic, geometric and mechanical characteristics. The results guide engineers in the structural design of houses.

System-Scale: In order to maximize the raw material strength as well as to cope with its weaknesses, critical elements for Technical Performance are structural Connections, which exist from the foundation to wall and wall to roof. Connections have to be developed also according to the Cost Advantage criterion as well as the Maintenance one. The system scale testing was shaped further by the criteria Skill Demand, Modularization, and Implementation Pace. Further, the resistance of the building system to fire and lateral forces, as induced during earthquakes and strong winds, has been tested on system level to ensure durable performance.

Building-Scale: Building-Scale contains testing the building response on three-dimensional model houses. In full scale Typhoon Tests, the predicted laboratory performance has to be confirmed under real life conditions. Further, the Thermal Comfort during day to day performance is tested, as mentioned in the surveys to be an important criterion. Transparently evaluating the environmental impact of the structure compared to conventional solutions is captured in Life Cycle Impact Assessment. All results on material, system, and building scales finally lead towards the ability of a legal approval as building concept in the Philippines. On building scale, finally also the economic criteria have found consideration through measuring economic indicators.

For each of the research topics, specific one-dimensional quantitative testing methods are identified to generate data with scientific validity as well as local and financial applicability for the given context. Both laboratory and field tests are included. Full reference to the testing standards named is given in the literature list [52,53,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

Figure 8.

Systemic approach on research about building concept.

Figure 8.

Systemic approach on research about building concept.

Selected initial results provide insights about characteristic strengths in Compression (fc,o,k = 20 MPa), Tension (ft,o,k = 95 MPa), Shear (fv,k = 5 MPa) and Bending (fm,k = 34.6 MPa) as well as a Modulus of Elasticity MOE at 5th percentile (E0.05 = 8600 MPa), tested according to [52]. The recommended shear wall raking strength, determined according to [63], was found to be 8 kN/m for walls cladded from both sides. A fire rating of 60 min resistance according to [65] and compliance to local regulations for seismic and wind forces according to [66] was obtained. The environmental impact assessment according to [62] showed a 60% reduction of CO2 emissions compared to the conventional concrete building. In a thermal comfort assessment, a healthy indoor climate was determined due to a climate adjusted house design and the choice of the building material [61,67]. In studies about the resistance of the houses during real-life typhoon impacts since 2012, the houses withstood inner and outer wind bands of five typhoons ranging from 140 to 180 kph, including twice being hit by the eye of typhoons during three typhoon seasons. No structural damage was observed during and after these extreme impacts, which confirms the calculated structural performance according to [68]. The combination of all of above results enable an application for nationwide legal approval in the Philippines such as [59] or [69].

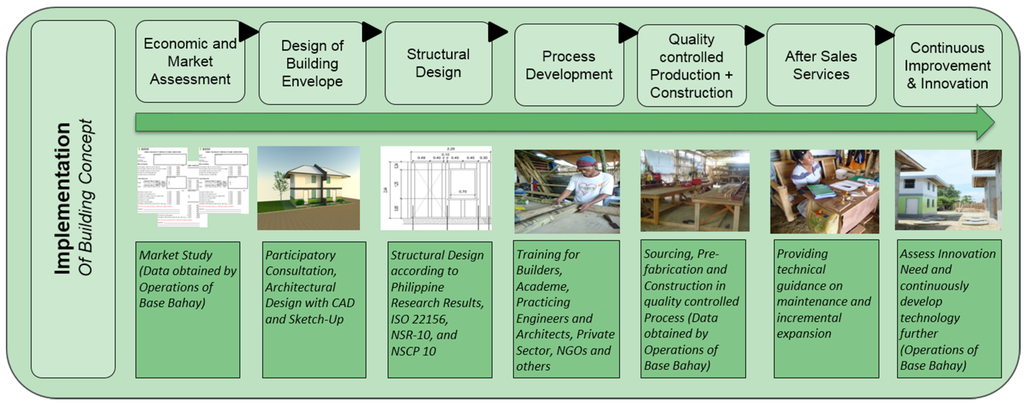

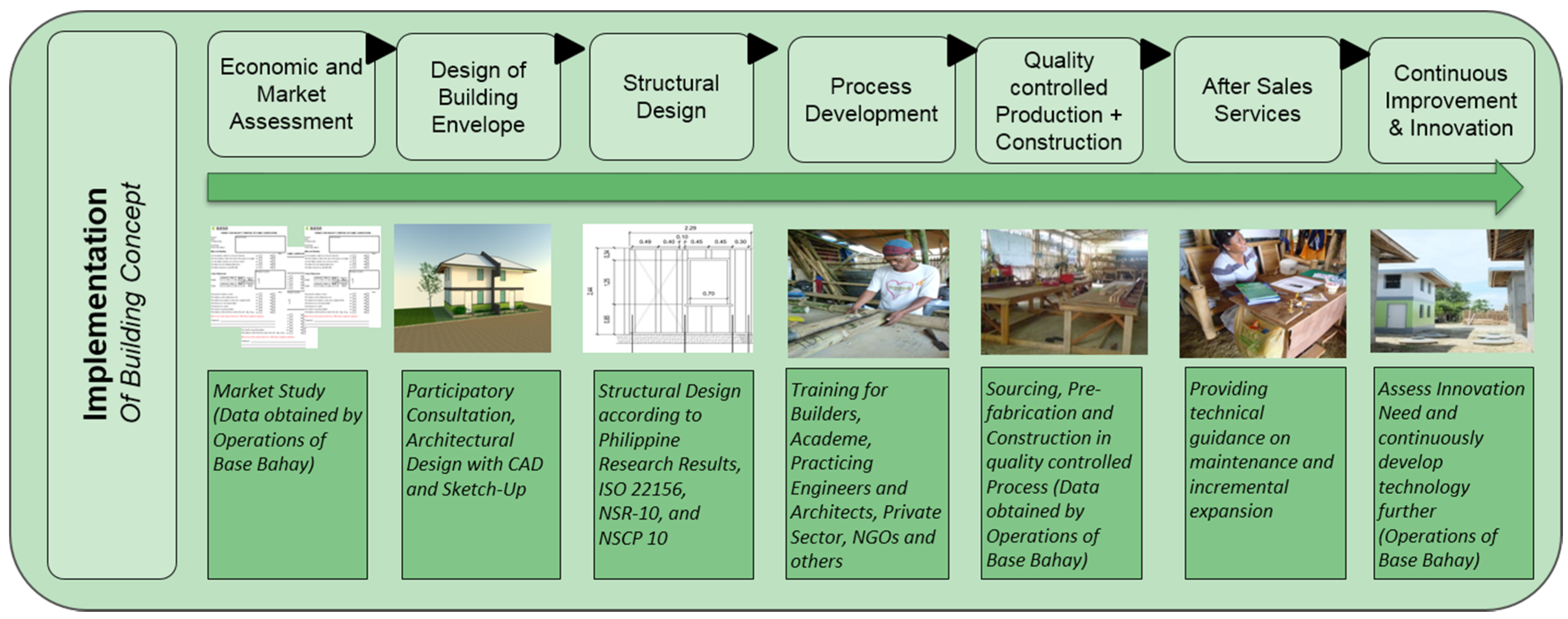

- (2)

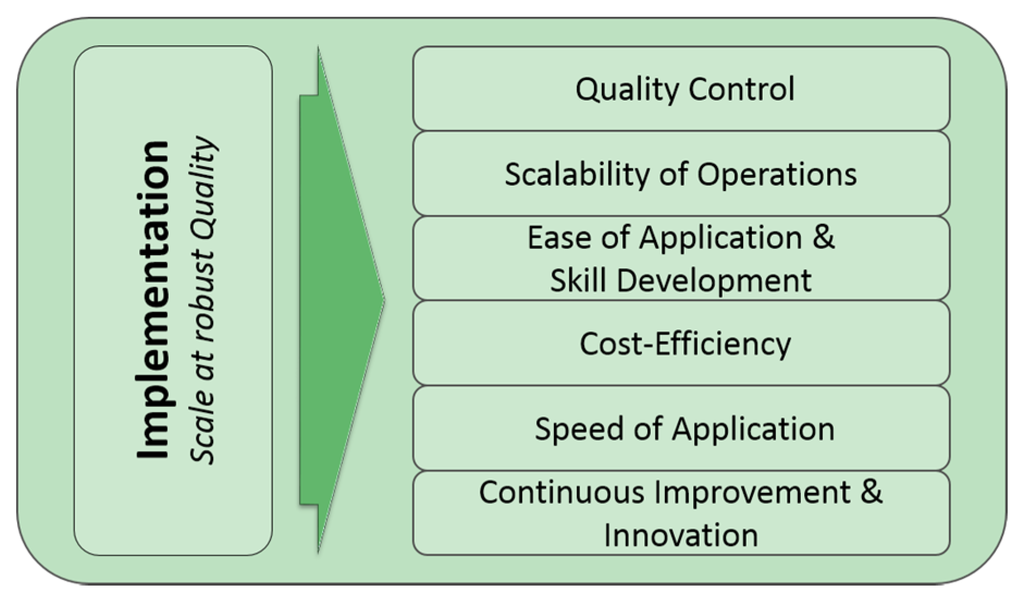

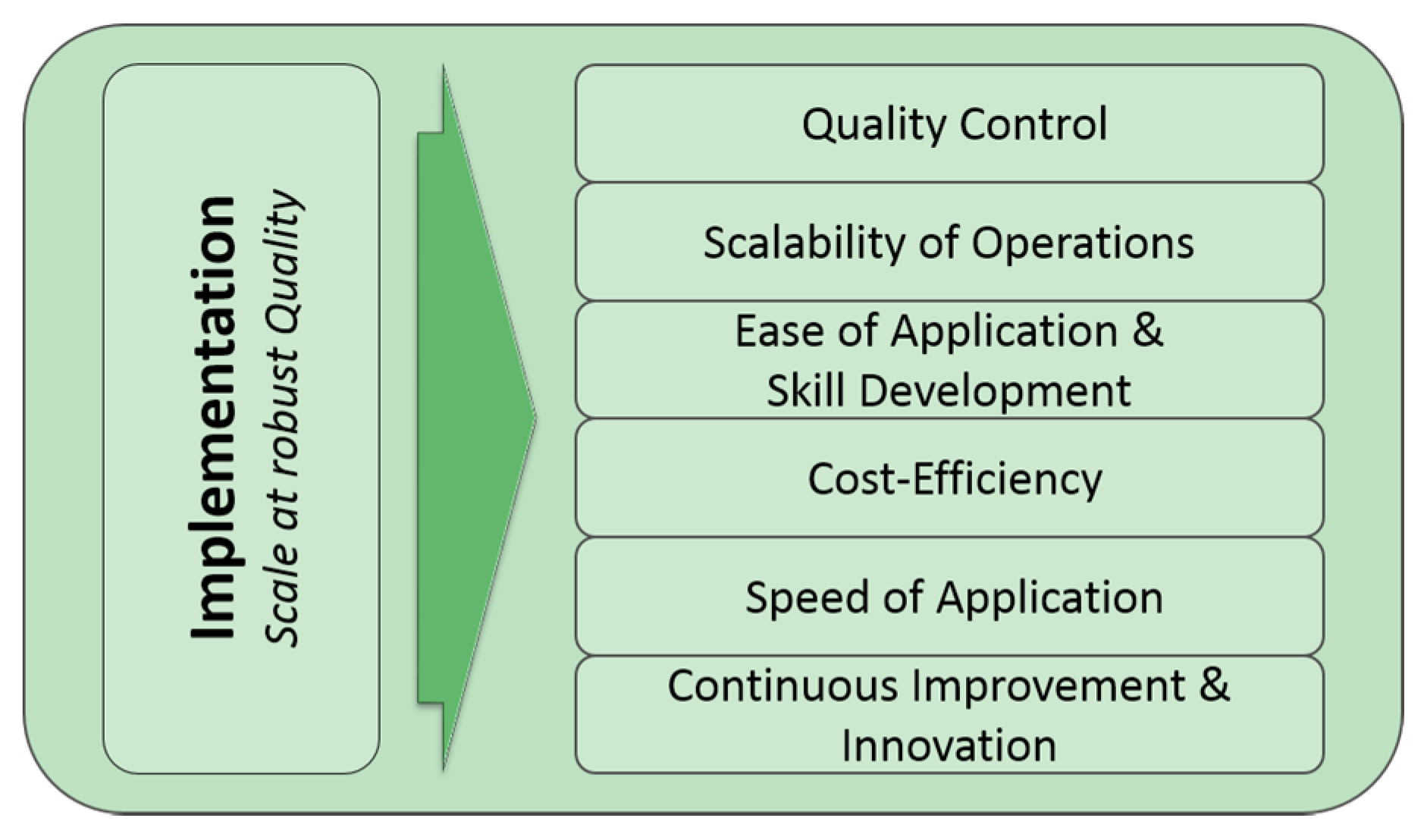

- The research strategy is complemented with a parallel, slightly time shifted implementation strategy, which contains selected implementation actions. Latter cover the pillars Technology, Society and Economy. With 7 of the 15 Sustainability Criteria, an implementation strategy at scale and robust quality is shaped: Quality Control for robust technical performance, Ease of Application and Skill Development, Construction speed and scalability, Innovation through participation and evaluation of practicability of concepts, as displayed in Figure 9. Finally, previously theoretical Economic Indicators were verified through implementation projects. It can be noted, that all criteria were already considered in the System Scale and Building Scale research strategy and are now verified through application in the field. In 2012, six demonstration houses were built, since then another 150 houses have been implemented [46].

Figure 9.

Continuous optimization criteria of technology implementation.

Figure 9.

Continuous optimization criteria of technology implementation.

For the application in the given context, the concept of Prefabrication was chosen. It stands in contrast to the traditional construction practices, where individual skilled community builders guide teams to a performing result. Latter is the dominating method in the bamboo sector, both in the Philippines and around the globe. Prefabrication is a well-established concept for light weight construction with timber in Europe and has been applied on pilot scale with bamboo in Latin America. While both concepts have their justification, the Sustainability Criteria highlight the relevance of scalability, quality control and cost-efficiency. Prefabrication facilitates a quality-controlled production of load bearing elements and increases the pace of construction of construction projects. Given the climatic context of the Philippines, with immense sunshine and strong seasonal rainfalls or winds, it is of value to reduce construction time to a minimum and with that exposure of humans to the elements. Below Figure 10 provides an example of a pre-fabricated bamboo frame house with the assembled load bearing structure on the left, one prefabricated frame in the middle in two stages of finishing and a fully finished house on the right side.

Figure 10.

Modern bamboo-based housing built in Iloilo, Region IV in 2015 by [46,49].

Figure 10.

Modern bamboo-based housing built in Iloilo, Region IV in 2015 by [46,49].

Next to the criteria reliable quality and pace on construction site, ease of construction, as well as needed skills have been important elements for the iterative optimization process. The construction with prefabricated frames reduces the skills needed on construction site and transfers them into the production hall, where capacity can be built for. Expanding skills of bamboo craftsmen contributes to preserving selected traditional skills, while transforming them where needed to a recognized knowhow of today`s industry. The use of conventional mortar finishing covering the bamboo-based frame is important for an enduring technical performance, fire and typhoon resistance, user-comfort, and low maintenance needs. In reference to the identified after-sales service gap in Colombia, easily available technical support for post-occupation services was deemed important.

Figure 11 summarizes the identified one-dimensional implementation actions and methods for data generation. Compared to the research strategy, the implementation strategy contains both quantitative methods, such as the one for structural design of houses, as well as qualitative methods such as trainings, quality control concepts, participatory consultations, and an innovation enabling environment. Reference is given to the suggested methods in the literature list [54,66,68].

Figure 11.

Systemic approach on implementation of building concept.

Figure 11.

Systemic approach on implementation of building concept.

- (3)

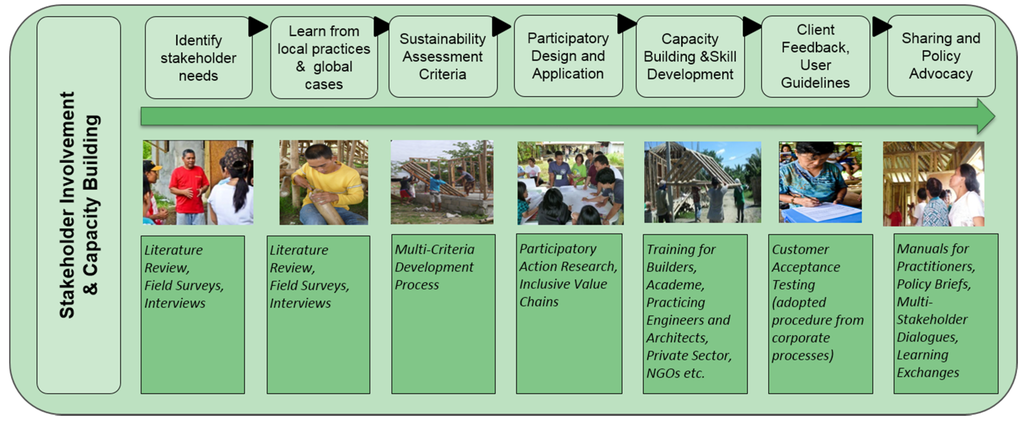

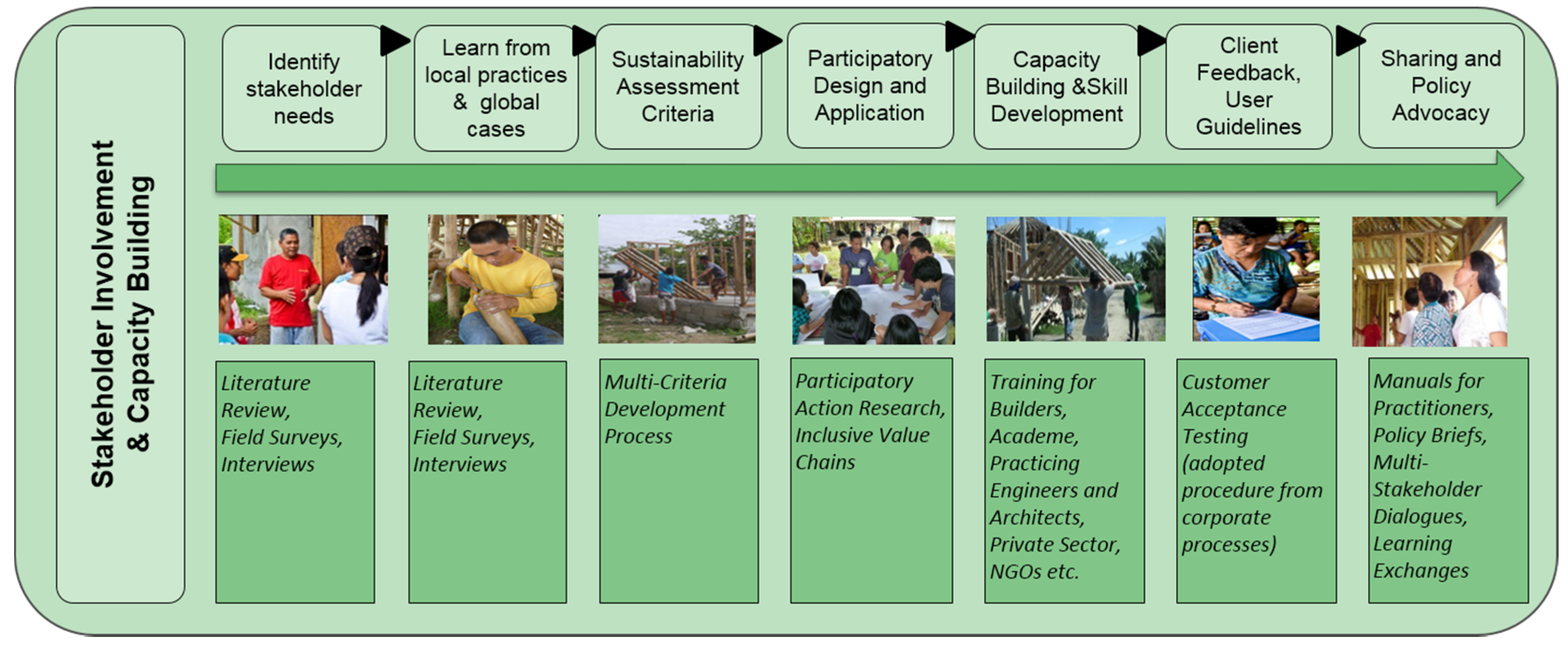

- Stakeholder participation, capacity building and a close interaction between low-income groups, professionals, governments and further stakeholder groups was reflected through a strategy on stakeholder involvement, displayed in Figure 12. The participatory process gives consideration to the need and concerns of low-income groups in planning, construction, and post-occupation. The strategy describes where and how participation and capacity building has been integrated in the technology development. Continuous process simplifications and parallel skill development facilitate involvement of people. Post occupational customer acceptance testing according to corporate standards allow to identify further innovation potentials and are therefore connected to the area ‘innovation’ in the implementation roadmap. Policy approval and expansion has been targeted through national, regional and global best practice sharing and advocacy and is connected to the area of legal approval under research.

Figure 12.

Systemic approach on integrating of stakeholder requirements.

Figure 12.

Systemic approach on integrating of stakeholder requirements.

- (4)

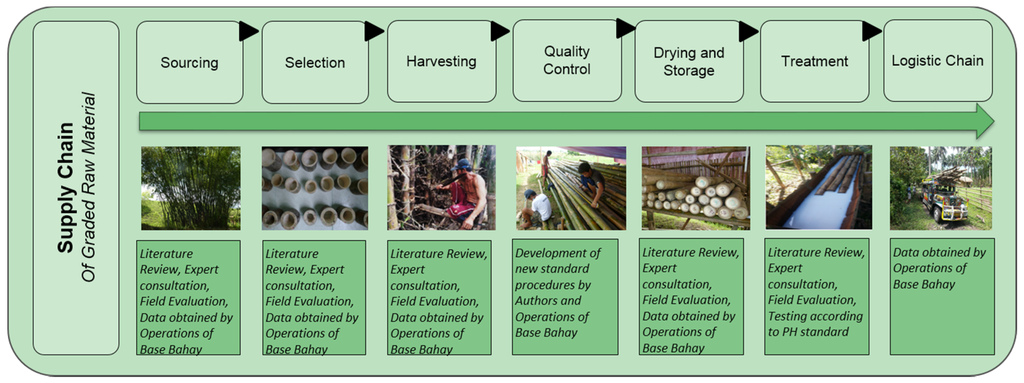

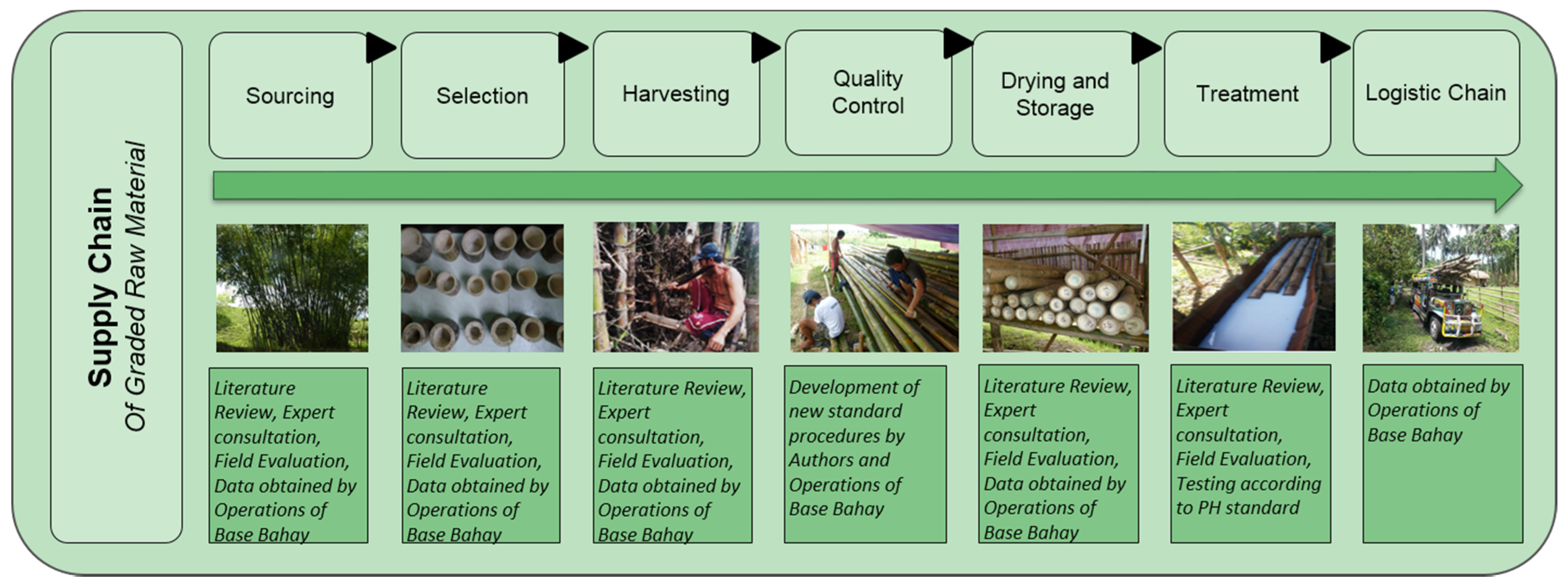

- Further, the technology application at larger scale requires a sustainably generated, accessible supply of quality graded bamboo. Bamboo has to become a standardized, reliable forest product in the Philippines. In the field surveys and interviews, this was highlighted as critical item and therefore specified as one of the implementation strategies. Existing bamboo stands have to be identified through field surveys and/or more technologic aerial mapping. Forming of supply networks and harvesting trainings the management of these stands can be strengthened and sustainable harvesting amounts determined. Durable, reliable, raw material quality has to be produced through a defined drying, storage, and treatment process, which follows quality control, environmental- and health-criteria as well as efficient technical processes. Research on treatment methods is one essential component for bamboo, since there is no scientific recommendation without bottlenecks available as per today. All items on the road map are summarized in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Systemic approach on supply chain of strength graded raw material.

Figure 13.

Systemic approach on supply chain of strength graded raw material.

4. Discussion

This chapter discusses the results presented in the chapter before according to the criteria validity and transferability of methodology and results.

Method: Validity of using qualitative data

- -

- This paper derives Sustainability Assessment Criteria through qualitative research methods such as interviews and field observations. Science debates about the validity of qualitative assessments in comparison to quantitative ones. Seemingly less transparent evaluation methods are among the most common criticisms, which is opposed by researchers describing the strength of qualitative data analysis [44,70], when carried out systematically and holistically. Typically, qualitative sample sizes are limited, but rich in data [40]. The paper addresses the concerns through a systematic data generation and content analysis including coding, sorting and sifting of data. The evaluation of qualitative data is moreover based on human characteristics, understanding, knowledge, and social context allowing for an encyclopedic evaluation of an issue or case [44]. The paper has overcome the risk of biased findings through scientifically recognized validation methods such as: triangulation through multiple sources, long-term engagement in the field, application of multiple methods to validate findings, and the evaluation through more than one observer or author.

Method: Validity of presenting a roadmap for development

- -

- This paper looks at an innovation potential, for which data has to be generated first, before it can be compared. The results can therefore be understood as Part 1 of a MCDM. Once all suggested data sets are generated and comprehensively evaluated, a holistic performance comparison between the alternative and the conventional building method is enabled. At this point, a Part 2 of the paper is suggested, which will provide a technology raking and recommendation for decision-makers.

Transferability: Application in further geographies

- -

- This paper assesses an alternative method for house construction in the socio-economic and geographic boundaries of the Philippines. In [32] it is highlighted, that there is a call for Sustainability Assessments to transfer from local to global level. A fine balance is to strike for creating sufficiently meaningful data for the local context, and the wish to create valid generalizations and transfers [71]. Sustainability assessments in Development Cooperation are often found to be specific, e.g. due to their specific cultural context [72]. While this paper assessed the Philippine context of social housing, the strategic approach for creating sustainable building solutions has general validity for the tropical context and low-rise construction. It can therefore be adapted to other bamboo growing countries under integration of local specifications. The Philippines, with its natural disasters, its low affordability and high poverty, represents further a challenging environment for a building technology and can therefore be seen as pathfinder for an expansion in Asia-Pacific or around the globe. However, for it to be successfully applied at scale, a complex set of wider interlinked aspects has to be tackled.

Transferability: Application to further building materials or sectors

- -

- For increasing the impact of Sustainability Assessments, a transfer from product to sector level is suggested in [32]. This paper captures stakeholder requirements on the sector level of social housing. The organic material bamboo brings about requirements, which are nearest to the sectors of other forest products. Nevertheless, its specific supply chain and technical construction concepts remains connected to bamboo and requires adjustment when other materials are considered.

5. Conclusions

The general objective of the paper to develop a roadmap for transforming the potential bamboo raw material into a sustainable building technology suitable for social housing in the Philippines has been achieved. Fifteen context-specific Sustainability Assessment Criteria have been identified through processing of qualitative stakeholder data. Data was categorized into one or several of the sustainability dimensions society, ecology, economy, technology, or governance and processed through multiple qualitative sampling strategies. The paper then presented a roadmap describing a multi-perspective development process showing the implementation path for the theoretic potential. The roadmap contains 28 action items derived by correlation of the Sustainability Criteria with four Implementation Strategies: (1) Research about and (2) implementation of the technology, (3) Stakeholder participation; and (4) Supply chain development. For generating measurable results in these 28 action items, quantitative and qualitative recognized one-dimensional methods are named. Once the action items are put into practice, the generated one-dimensional data will enable multi-dimensional, holistic performance assessment of the alternative building technology as suggested by Multi-Criteria Decision Making theory. As such, the paper contributes to enable future guidance for decision-makers whether or not to change current systems from a consumer-, policy-maker, or construction-professional viewpoints. With that, the approach described in this paper brings attention to an unexplored, highly relevant research field for the future: sustainable and resilient building for low-income dwellers in rapidly growing urban centers in Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement is given to Base, an initiative of Hilti Foundation on sustainable affordable housing, which has funded this research. Furthermore we acknowledge Chalmers Area of Advance Built Environment profile “Responsible Use of Resources” to support the affordable building-related research. Thirdly, the contribution of Bambou Science et Innovation is highly valued.

Author Contributions

The study was designed and the article was written by Corinna Salzer. Holger Wallbaum contributed to the methodology framework of the research. Jean Luc Kouyoumji contributed content to the comparison with Timber construction in Europe, Luis Felipe Lopez to Bamboo Construction in Latin America, and all three to triangulate the method selection for individual information units of the roadmap.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Interview Guide for different stakeholder clusters:

Table A1.

Guide for Interviews with stakeholder clusters (1) and (3A).

| No. | Stakeholder Clusters: (1) Inhabitants of Traditional Bamboo Houses in the Philippines and (3A) Low Income Groups in Need of Social Housing |

|---|---|

| 1 | Since when have you lived in your current house, with how many family members do you live there and what is the size of the house? |

| 2 | What is the material your current house is made from? Why did you choose it? |

| 3 | How do you like living in your current house? Have you ever lived in a different house? How was it in comparison to now? |

| 4 | Have you been involved in the construction of your house? |

| 5 | Do you know where the materials of your house were sourced? |

| 6 | Do you feel save in your house during earthquakes or typhoons? Have you experienced damage to your house during extreme impacts? |

| 7 | What is your current source of income? How high is your monthly income? |

| 8 | How much did you spend for the construction of your house? Do you still pay the installments? |

| 9 | How often do you have to maintain your house? |

| 10 | Which building method would you prefer if you could freely choose? |

Table A2.

Guide for Interviews and Expert Review with stakeholder clusters (2A) and (2B).

| No. | Stakeholder Clusters: Building Sector using Forest Products in (2A) Latin America and (2B) Europe |

|---|---|

| 1 | At which scale is the forest product being used for house construction today/What is its current market share? What is the track record of the technology? |

| 2 | Among which customer group is the building technology applied the most? |

| 3 | What is the dominating perception towards this building technology- by its users and non-users? How is the customer acceptance of the technology in general? |

| 4 | Were or are there major barriers hindering the application of a building technology using bamboo in the pillars economy, ecology, society, technology, or governance? |

| 5 | Were or are there major drivers/opportunities supporting the application of a building technology using bamboo in the pillars economy, ecology, society, technology, or governance? |

| 6 | What roles do human skills and capacity building play? |

| 7 | What is the common construction process and how relevant are specific optimization processes/concepts? |

| 8 | What role does research and development and innovation play in general? |

| 9 | What role does the supply chain play? |

| 10 | What roles do government policies or incentives and environmental concerns play? |

Table A3.

Guide for Interviews with stakeholder cluster (3B–3D).

| No. | Stakeholder Clusters: Stakeholders in Social Housing in the Philippines (3B–3D) |

|---|---|

| 1 | How big is the housing need in the social housing segment? How many houses are currently supplied by your organization specifically and private sector, government, NGOs or self-build homes in general? Is there a gap between supply and need? |

| 2 | What are requirements in social housing, how would you describe the needed value proposition? |

| 3 | What are the most common building materials and concepts applied in low-cost housing segments? |

| 4 | What role does perception towards a building material for its success at the market play and how do you evaluate the perception of bamboo today? |

| 5 | Were or are there major barriers hindering the application of a building technology using bamboo in the pillars economy, ecology, society, technology, or governance? |

| 6 | Were or are there major drivers / opportunities supporting the application of a building technology using bamboo in the pillars economy, ecology, society, technology, or governance? |

| 7 | What roles do human skills and capacity building play? |

| 8 | What is the common construction process and how relevant are specific optimization processes/concepts? |

| 9 | What role does research and development and innovation in general play? |

| 10 | What roles do supply chains play? |

| 11 | What roles do government policies or incentives and environmental concerns play? |

Table A4.

Guide for Semi-Structured Interviews with stakeholder cluster (3E).

| No. | Stakeholder Clusters: Raw Material Suppliers for Housing Made from Bamboo (3E) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Which bamboo species do you sell? |

| 2 | In which quantity this species would be harvestable? |

| 3 | What is the regular price for bamboo for purchase at harvesting location? |

| 4 | Do you regularly supply customers with bamboo or just provide it on an occasion/demand basis? |

| 5 | Can the bamboo be delivered to collection points and what are prices including this transportation? |

| 6 | What is the timeline from harvesting to delivery and which mode of transport would be chosen? |

| 7 | Are there any middle men, consolidators, or sub-contractors involved? |

| 8 | What is the income share between land owner, harvester, and transport? |

| 9 | Is bamboo supply the only source of income or one among others? |

| 10 | Would you be interested in extending your bamboo business in the future? |

References

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)-SBCI. Buildings and Climate Change: Summary for Decision-Makers; UNEP: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]