Transition Thinking and Business Model Innovation–Towards a Transformative Business Model and New Role for the Reuse Centers of Limburg, Belgium

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. The Social Enterprise and Its Future Role

2.2. Conceptual Background

- -

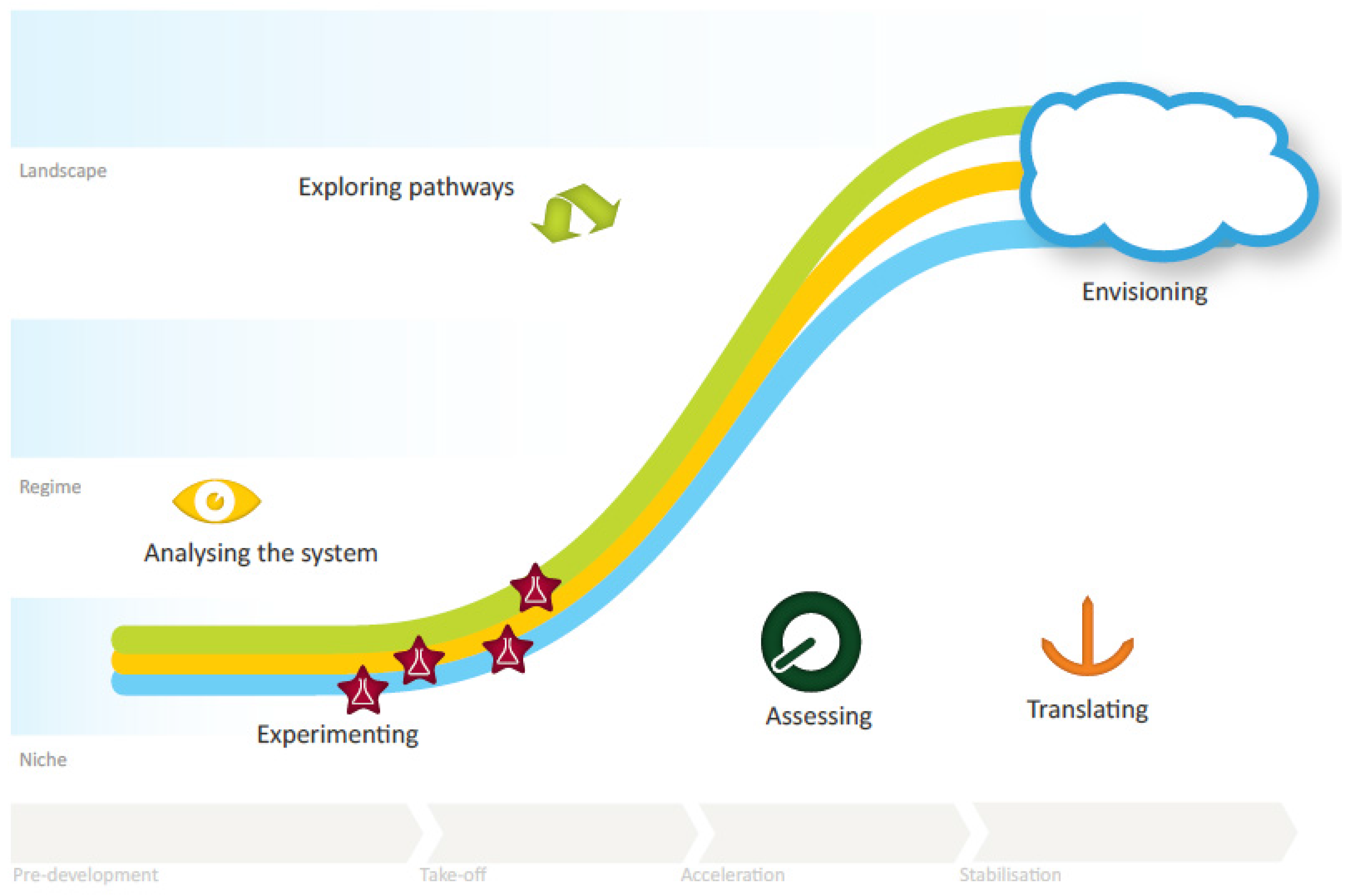

- Understand how the current systems functions, what does and what does not work, what is appropriate and what is not (analyzing the system).

- -

- Imagine how we would like the future system to look like and function, what is desirable, what is sustainable (envisioning).

- -

- Explore how we can evolve from the current situation to the envisioned system and what trend breaks are required (exploring pathways).

- -

- Explore how the chosen pathways can be translated into practical actions and how the trend breaks can be induced (experimenting).

- -

- Monitor the transition process through follow-up and reflection on all actions, events, policies and strategies that influence the transition in question; and hence feed a process of social learning, which is a prerequisite for eventual success (assessing).

- -

- Translate the lessons learnt into change-inducing actions in order to incrementally transform (“transitionize”) the system, closer to a dynamic sustainable equilibrium (translating).

2.2.1. A Process to Promote Strategic Agency

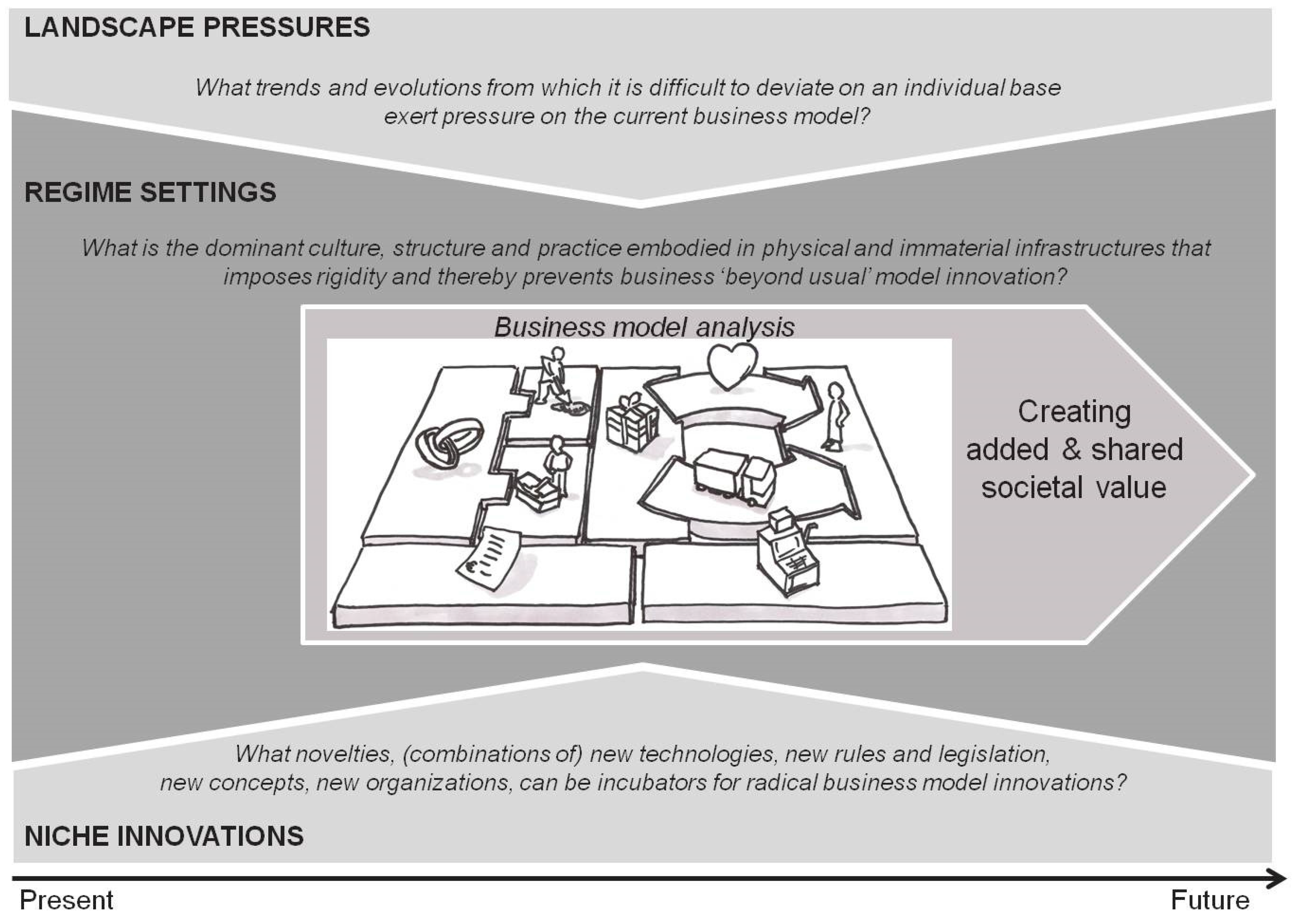

2.2.2. A Process of Reflexive Design

- -

- At the landscape level “gradients of force” are in play: dominant trends and evolutions from which it is difficult to deviate and which are rigid in the sense that it is difficult to change them on an individual base (e.g., globalization, climate change, ageing populations, etc.). Nevertheless, these prevailing evolutions and trends exert external pressure on the systems in place.

- -

- A “regime” refers to the dominant culture, structure and practice embodied in physical and immaterial infrastructures (e.g., roads, power grids, routines, actor-networks, regulations, government and policy, etc.). Regimes are the backbone of the stability of societal systems and have a characteristic rigidity that very often prevents innovations from altering the standing structures fundamentally.

- -

- Niches are often little visible small scale segments in society. In such protected environments, novelties are created and tested. These novelties can be (combinations of) new technologies, new rules and legislation, new concepts, new organizational arrangements, etc. Niches contain incubators for transition experiments and proofs of concept of radical innovations.

2.2.3. A Co-Creative Endeavor

| PHASE Ia: Envisioning and Transition pathways | |

| Internal group of 5 directors | Transition arena |

|

|

| PHASE Ib: Anchoring | |

| Internal group of 5 directors + IMWC | |

| |

| PHASE II: Feasibility study | |

| New consortium of five partners (2 directors, IMWC, transition research team and social innovation consultant) | |

| |

| PHASE III: Towards a Mandate for Transformative Action | |

| Three reuse centers and their company boards | |

| |

| PHASE IV: Towards an in-between organizational mode? | |

| Three reuse centers and their company boards (communication with 2 other reuse centers) | |

| |

3. Results

3.1. Investigating the Regime Context

3.2. Phase I: Envisioning and Transition pathways

(1) The business canvas exercise

(2) Arena 1: From BM canvas to BM in the wider dynamics of change

(3) Arena 2: From “as is” to “to be”

(4) Arena 3: From vision to practice

(5) The synthesis workshop

(6) Towards a concept note and engagement declaration

(7) Exchanging visions and elaboration of a new management agreement

(8) Towards a new management agreement between the reuse centers and the intermunicipal waste company

- ≫

- Anchorage of a changed logic of value creation, i.e., shifting from being subsidized to being rewarded for the societal and environmental services by means of a reorientation of the current financial model. This would allow the reuse centers to employ more personnel and increase their environmental services which is not possible in the old subsidy model.

- ≫

- Exploring new organizational arrangements between the reuse centers and the IMWC.

- ≫

- Inserting an addendum to the management agreement providing space for joint experiments focusing on: (1) new ways to deal with resources/new resource distribution options that favor more effective product reuse or upcycling; and (2) new roles for reuse centers that can be developed.

3.3. PHASE II: Feasibility study

(9) Defining core elements of a future collaboration

- ≫

- close collaboration between all reuse centers in the province of Limburg, in order to be able to act as one negotiation partner with the IMWC Limburg.net and to guarantee a uniform way of working within the whole province;

- ≫

- win–win collaboration with social economy players as well as private partners, no competition;

- ≫

- objective of the reuse centers remains focused on the creation of employment for disadvantaged people;

- ≫

- initiatives must be financially viable and create added value for society;

- ≫

- transparency and openness in financial and other data; and

- ≫

- clear agreements on ownership of waste fractions (and their associated costs or revenues).

(10) Preparing the value proposition and customer profile for the new activities to be developed

- ≫

- What is the value proposition of the service? What need is being addressed?

- ≫

- Who is the targeted customer?

- ≫

- Who are potential partners?

- ≫

- Who are our competitors? Can we turn them into partners?

- ≫

- What are associated costs/revenues?

- ≫

- How can we design the service to best serve the client?

(11–14) Collecting and exchanging data

(15) Designing practical pilot field trials

- ≫

- Estimate the effect of a less rigid policy in reuseable goods collection: no longer refusing goods that are not reuseable eases the relationship between the goods collectors on the field and the clients, which might lower the barrier for clients to make use of the collection service by the reuse centers and can possible increase the intake of reuseable goods. Clients are often not aware of which goods are reuseable and which are not, which can lead to discussions in the field.

- ≫

- Gaining experience with the service of bulky waste collection: to explore the practical feasibility of the work and gain some experience with the aspects it comprises, including an estimation of the additional volume of re-usable goods that can be collected through this route.

- ≫

- Gaining experience with dismantling and sorting of non-reuseable items: how much time does it take (cost estimation), what competences are needed, what type of materials can be produced and what revenues can be expected from this activity.

(16) Analyzing pilot trials on bulky waste and building scenarios for feasibility analysis

(17) Designing and financial analysis of a new business model for textile collection and valorization

(18) Designing a potential overarching collaboration structure

3.4. PHASE III: Towards a mandate for transformative action

(19) Validating the vision and presenting findings from the feasibility study

3.5. PHASE IV: Towards an in-between Organizational Mode?

(20) Next steps

4. Discussion

4.1. Business Model Innovation as Unusual

- ≫

- to adopt systemic thinking [25];

- ≫

- ≫

- ≫

- to select and orient short term innovation processes in line with the long term ambitions [23];

- ≫

- to involve relevant governance actors open to transformative change to promote institutional innovation [32]; and

- ≫

- to stimulate explorations around transformations of current resource distribution and the marshaling of new resources [30].

4.2. Action Research as a Catalyst for Shaping a Different Economic Platform

4.3. Case Specific Lessons Learnt

- ≫

- promote systemic thinking about the bigger picture, the factors, actors, trends and possible threats and opportunities affecting the current business model;

- ≫

- align the business model innovation process with the ongoing dynamics on the regime level;

- ≫

- induce a new discourse with a higher ambition level, fueled by an ambitious long term vision;

- ≫

- promote the development of new business model concepts (material matchmaker and the service matchmaker) that fit in an envisioned future society that functions within the boundaries of significantly different material management principles;

- ≫

- connect the long term vision to short term action through the follow up feasibility study that started in 2014 and the initiation of a new organizational mode;

- ≫

- promote institutional innovation by opening up opportunities to anchor the new roles and activities in the new business management agreement with the IMWC (impacting the wider governance setting) allowing experimentation and reorientation of the future role while at the same time offering stability in current practices. Unfortunately, this new management agreement failed because three reuse centers dropped their support in the final stage;

- ≫

- prompt diffusion of the new business model concepts into new innovative networks and governance midst;

- ≫

- mobilize people and money for follow up activities and practice-based experiments;

- ≫

- raise support from the company boards for further investment in the business model transformation discourse;

- ≫

- prompt a dialogue on changing organizational arrangements and exploring new collaborations and roles; and

- ≫

- promote further reflection on how to proceed next; e.g., exploring a merger as an important in-between state that can provide more space for the further transformation of their business model.

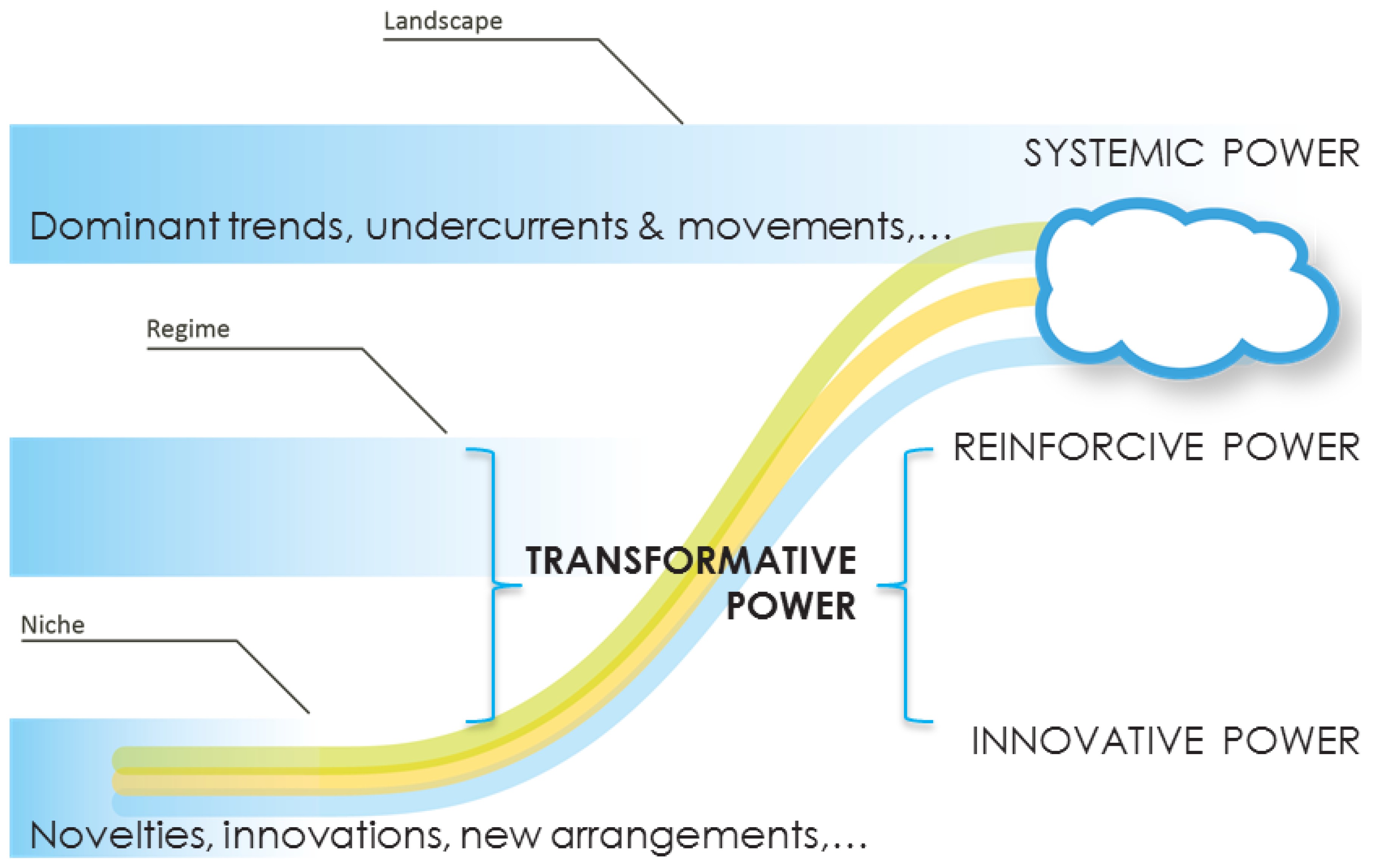

4.4. Fueling Innovative and Transformative Power

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinssen, P. The Network Always Wins; Mcgraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, N.; Lemoine, G.J. What VUCA Really Means for You. Available online: https://hbr.org/2014/01/what-vuca-really-means-for-you (accessed on 19 January 2016).

- Jonker, J. Nieuwe Business Modellen. Samen Werken Aan Waardecreatie. Stichting Our Common Future 2.0; Doetinchem & Jan Jonker. Stichting OCF 2.0 and Academic service: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “sustainability business model”. Org. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation. Categories and interactions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.; Rahbek, G.; Gardetti, M.A. Introduction. J. Corp. Cit. 2015, 57, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Blühdorn, I. The governance of unsustainability: Ecology and democracy after the postdemocratic turn. Environ. Polit. 2013, 22, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Bergendahl, M.N.; Gregory, M.; Ryan, C. Towards a Sustainable Industrial System. With Recommendations for Education, Research, Industry and Policy; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development. New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation. A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hvass, K.K. Business Model Innovation through Second Hand Retailing: A Fashion Industry Case. J. Corp. Cit. 2015, 57, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building Social Business Models: Lessons from the Grameen Experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Model Behavior. 20 Business Model Innovations for Sustainability; SustainAbility: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2014.

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Towards better understanding of transitions and their governance: A systemic and reflexive approach. In Transitions to Sustainable Development. New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Grin, J., Rotmans, J., Schot, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, J. Understanding transitions from a governance perspective. In Transitions to Sustainable Development. New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Grin, J., Rotmans, J., Schot, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.W. Seizing the White Space. In Business Model Innovation for Growth and Renewal; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lovins, A.B.; Lovins, L.H.; Hawken, P. A Road Map for Natural Capitalism. Available online: http://www.natcap.org/images/other/HBR-RMINatCap.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2016).

- Tukker, A.; Tischner, U. (Eds.) New Business for Old Europe. Product-service Development, Competitiveness and Sustainability; Greenleaf: Sheffield, UK, 2006.

- Hansen, E.G.; Große-Dunker, F.; Reichwald, R. Sustainability innovation Cube. A framework to evaluate sustainability-oriented innovations. Int. J. Inn Man. 2009, 13, 683–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorissen, L.; Manshoven, S.; Vrancken, K. Tailoring business model innovation towards grand challenges: Employment of a transition management approach for the social enterprise “Reuse Centers”. JGR 2014, 5, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J. In Het Oog Van De Orkaan. Nederland in Transitie; Aeneas: Boxtel, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; van Bakel, J.C.; Whiteman, G.; Rotmans, J. Business strategies towards sustainable systems. Bus Strat. Environ. 2010, 19, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; De Weerdt, Y.; Gorissen, L.; Berloznic, R. Transition in Research. Research in transition. When Technology Meets Sustainability; VITO NV: Antwerp, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino, F. Power in Transition. Empowering Discourses on SustainabilityTransitions. Ph.D. Thesis, Wöhrman Print Services, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management. New Mode of Governance for Sustainable Development. Available online: http://repub.eur.nl/pub/10200 (accessed on 19 January 2016).

- Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases. Futures 2010, 42, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Complexity and Transition Management. J. Ind. Ecol. 2009, 13, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Rotmans, J. Power in Transition. An Interdisciplinary Framework to Study Power in Relation to Structural Change. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2009, 12, 543–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions and System Innovations: A Co-Evolutionairy and Socio-Technical Analysis; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Paredis, E.; Block, T. The art of coupling. In Multiple Streams and Policy Entrepreneurship in Flemish Transition Governance Processes; Policy Research Centre TRADO: Ghent, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). System Innovation Synthesis Report; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Limburgse Kringloopcentra Maken de Cirkel Rond. Samen Bouwen aan een Inclusieve Circulaire Economie en een Klimaatneutraal Limburg. Available online: http://www.vitoduurzaamheidsverslag2012.be/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/KringloopcentraLimb.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2016). (In Dutch)

- i-Cleantech Flanders. The province of Limburg and its companies invest in cleantech. Press release 06/09/2013. Available online: http://www.greenville.be/new/uploads/pdf/persbericht-projecten.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2016).

- Manshoven, S.; Vanasshe, S.; Van Dyck, S. Material Match Maker; VITO NV: Antwerp, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- i-Cleantech Vlaanderen. Eindrapport Haalbaarheidstudies; i-Cleantech Vlaanderen: Provincie Limburg, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Taanman, M.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Diepenmaat, H. Monitoring on-going vision development in system change programmes. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2012, 12, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J. Reflexive modernization as a governance issue, or designing and shaping re-structuration. In Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Voss, J.P., Bauknecht, D., Kemp, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.; Kramar, R. CSR and the building of leadership capability. JGR 2010, 1, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.; Clark, W.; Alcock, F.; Dickson, N.; Eckley, N.; Jäger, J. Salience, Credibility, Legitimacy and Boundaries: Linking Research, Assessment and Decision Making. Faculty Research Working Paper Series; John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University: Harvard, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Schäpke, N. Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 9, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Rotmans, J. A dynamic conceptualization of power for sustainability research. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M. Market-focused sustainability: Market orientation plus! J. Acad. Market Sci. 2011, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Mena, J.A.; Ferrel, O.C.; Ferrel, L. Stakeholder marketing: A definition and conceptual framework. AMS Rev. 2011, 1, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raminez, E. Consumer-defined sustainably-oriented firms and factors influencing adoption. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2202–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gorissen, L.; Vrancken, K.; Manshoven, S. Transition Thinking and Business Model Innovation–Towards a Transformative Business Model and New Role for the Reuse Centers of Limburg, Belgium. Sustainability 2016, 8, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020112

Gorissen L, Vrancken K, Manshoven S. Transition Thinking and Business Model Innovation–Towards a Transformative Business Model and New Role for the Reuse Centers of Limburg, Belgium. Sustainability. 2016; 8(2):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020112

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorissen, Leen, Karl Vrancken, and Saskia Manshoven. 2016. "Transition Thinking and Business Model Innovation–Towards a Transformative Business Model and New Role for the Reuse Centers of Limburg, Belgium" Sustainability 8, no. 2: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020112

APA StyleGorissen, L., Vrancken, K., & Manshoven, S. (2016). Transition Thinking and Business Model Innovation–Towards a Transformative Business Model and New Role for the Reuse Centers of Limburg, Belgium. Sustainability, 8(2), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020112