Resident Knowledge and Willingness to Engage in Waste Management in Delhi, India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Questionnaire Survey Method

2.3. Sampling Method

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of the Respondents

3.2. Situation in Delhi: Waste Storage, Collection and Disposal

3.2.1. Waste Storage and Disposal

3.2.2. Doorstep Waste Collection

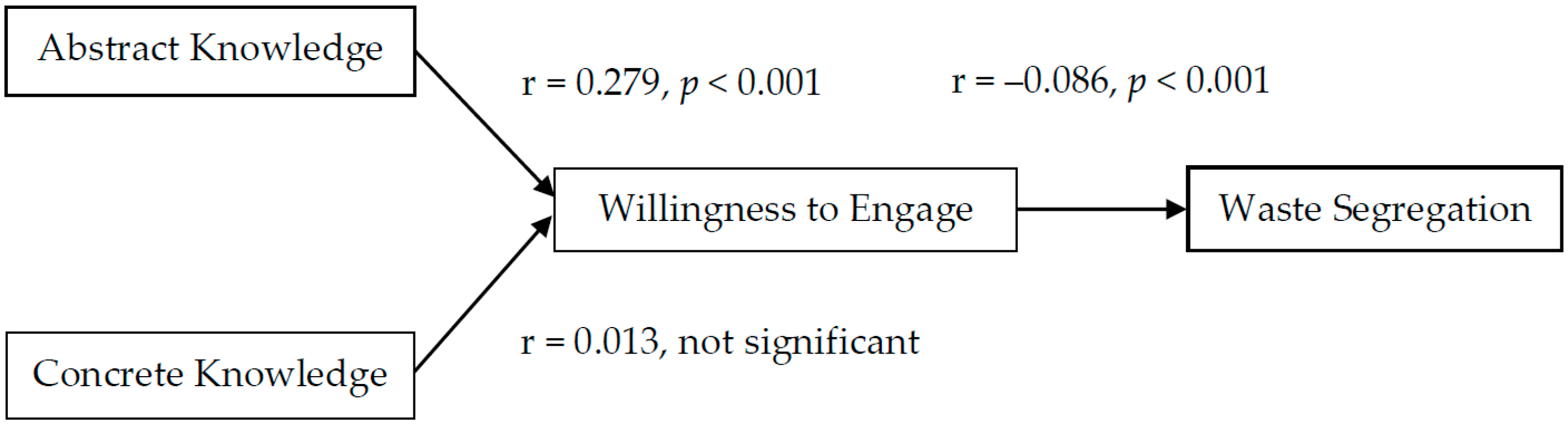

3.3. Abstract Knowledge, Concrete Knowledge, and Willingness to Engage in Waste Management

3.4. Difference of Abstract Knowledge among Different Socio-Economic Groups

3.5. Applicability of the Results to the Existing Waste Management System

4. Recommendations and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, N.; Yadav, K.K.; Kumar, V. A review on current status of municipal solid waste management in India. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 37, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharholy, M.; Ahmad, K.; Mahmood, G.; Trivedi, R.C. Development of Prediction Models for Municipal Solid Waste Generation for Delhi City. In Proceedings of National Conference of Advances in Mechanical Engineering; Jamia Millia Islamia: New Delhi, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The Energy and Resources Institute. TEDDY (TERI Energy Data Directory & Yearbook); The Energy and Resources Institute: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Talyan, V.; Dahiya, R.P.; Sreekrishnan, T.R. State of municipal solid waste management in Delhi, the capital of India. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Bhattacharyya, J.K.; Vaidya, A.N.; Chakrabarti, T.; Devotta, S.; Akolkar, A.B. Assessment of the status of municipal solid waste management in metro cities, state capitals, class I cities, and class II towns in India: An insight. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharholy, M.; Ahmad, K.; Mahmood, G.; Trivedi, R.C. Municipal solid waste management in Indian cities—A review. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central Pollution Control Board. Status Report on Municipal Solid Waste Management; Central Pollution Control Board: Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Delhi Waste Management. Available online: http://www.delhi.gov.in/wps/wcm/connect/environment/Environment/Home/Environmental+Issues/Waste+Management (accessed on 3 June 2016).

- Government of NCT Delhi; Government of India. Delhi Urban Environment and Infrastructure Improvement Project (DUEIIP) Delhi 21; Government of India: Delhi, India, 2001.

- Planning Commission. Report of the Task Force on Waste to Energy (Volume I): In the Context of Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management; Planning Commission: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Ramanathan, A.L. Solid Waste Management. Present and Future Challenges; I.K. International Publishing House: Bangalore, India, 2010; pp. 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, S. Solid Waste Management; Mittal Publications: New Delhi, India, 2010; pp. 215–217. [Google Scholar]

- East Delhi Muncipal Corporation Solid Waste Transportation Management System. Available online: http://mcdonline.gov.in/tri/edmc_mcdportal/dems/ (accessed on 3 June 2016).

- Hayami, Y.; Dikshit, A.K.; Mishra, S.N. Waste pickers and collectors in Delhi: Poverty and environment in an urban informal sector. J. Dev. Stud. 2006, 42, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipal Corporation of Delhi. Feasibility Study and Master Plan for Optimal Waste Treatment and Disposal for the Entire State of Delhi Based on Public Private Partnership Solutions. Volume 6: Municipal Solid Waste Characterisation Report; Municipal Corporation of Delhi: Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bringhenti, J.R.; Günther, W.M.R. Social participation in selective collection program of municipal solid waste. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 2011, 16, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, A.; Casagranda, M.; Zeni, A.; Girelli, E.; Rada, E.C.; Ragazzi, M.; Apostol, T. 3R’S from citizens point of view and their proposal from a case-study. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. D Mech. Eng. 2013, 75, 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo, G.; De Gisi, S. Public opinion and awareness towards MSW and separate collection programmes: A sociological procedure for selecting areas and citizens with a low level of knowledge. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 958–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junquera, B.; Del Brío, J.Á.; Muñiz, M. Citizens’ attitude to reuse of municipal solid waste: A practical application. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2001, 33, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Evangelinos, K.; Halvadakis, C.P.; Iosifides, T.; Sophoulis, C.M. Social factors influencing perceptions and willingness to pay for a market-based policy aiming on solid waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Hirose, Y. Expectation of empowerment as a determinant of citizen participation in waste management planning. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2009, 51, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D.; Iida, Y. Demonstrating the need for the development of internal research capacity: Understanding recycling participation using the Theory of Planned Behaviour in West Oxfordshire, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2006, 46, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Zeidi, I.M.; Emamjomeh, M.M.; Asefzadeh, S.; Pearson, H. Household waste behaviours among a community sample in Iran: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim Ghani, W.A.W.A.; Rusli, I.F.; Biak, D.R.A.; Idris, A. An application of the theory of planned behaviour to study the influencing factors of participation in source separation of food waste. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.F.; Malesios, C. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indhira, K.; Senthil, J.; Vadivel, S.; Appl, A.; Res, S. Awareness and attitudes of people perception towards to household solid waste disposal: Kumbakonam Town, Tamilnadu, India. Arch. Appl. Sci. Res. 2015, 7, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.; Nandini, N. Community attitude, perception and willingness towards solid waste management in Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 4, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Kumar, A.; Malaviya, P. Assessment of Environmental Behaviour among the Urban Poor of Panjtirthi Slum, Jammu, India. Curr. World Environ. 2015, 10, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasubramanian, P.; Saratha, M.M.; Divya, M. Perception of households towards waste management and its recycling in Coimbatore. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2015, 2, 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Dhokhikah, Y.; Trihadiningrum, Y.; Sunaryo, S. Community participation in household solid waste reduction in Surabaya, Indonesia. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 102, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallgren, C.A.; Wood, W. Access to attitude-relevant information in memory as a determinant of attitude-behavior consistency. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskamp, S.; Harrington, M.J.; Edwards, T.C.; Sherwood, D.L.; Okuda, S.M.; Swanson, D.C. Factors influencing household recycling behaviour. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 494–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, J.; Ebreo, A. What makes a recycler? A comparison of recyclers and nonrecyclers. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schahn, J.; Holzer, E. Studies of individual environmental concern: The role of knowledge, gender and background variables. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W. Conceptualising and analysing household attitudes and actions to a growing environmental problem. Development and application of a framework to guide local waste policy. Appl. Geogr. 2005, 25, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of India. Ministry of Home Affairs Census 2011. Available online: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/ (accessed on 14 October 2016).

- MapsofIndia.com. Map of MCD Delhi. Available online: http://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/delhi/mcd-corporation.html (accessed on 19 September 2016).

- MRSI Socio-Economic Classification 2011. The New SEC System. Available online: http://imrbint.com/research/The-New-SEC-system-3rdMay2011.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2016)).

- Government of India. Solid Waste Management Rules. Available online: http://www.moef.nic.in/content/so-1357e-08-04-2016-solid-waste-management-rules-2016 (accessed on 2 August 2016).

- Martin, M.; Williams, I.D.; Clark, M. Social, cultural and structural influences on household waste recycling: A case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2006, 48, 357–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, A.A.; Alavi, N.; Goudarzi, G.; Teymouri, P.; Ahmadi, K.; Rafiee, M. Household recycling knowledge, attitudes and practices towards solid waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 102, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, J. Thoughts on Poverty from a South Asian Rubbish Dump: Gender, Inequality and Household Waste. IDS Bull. 1997, 28, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, M. Household Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices in Solid Waste Segregation and Recycling: The Case of Urban Kampala Recycling: The Case of Urban Kampala. Zambia Soc. Sci. J. 2013, 2, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Du, P. The Determinants of Solid Waste Generation, Reuse and Recycling by Households in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam; Asian Institute of Technology: Bangkok, Thailand, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo, G.; De Gisi, S. Domestic separation and collection of municipal solid waste: Opinion and awareness of citizens and workers. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1297–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Chamorro-Premuzi, T.; Snelgar, R.; Furnhamd, A. Personality, individual differences, and demographic antecedents of self-reported household waste management behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, H.; Dawson, L.; Radecki Breitkopf, C. Recycling attitudes and behavior among a clinic-based sample of low-income Hispanic women in southeast Texas. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desa, A.; Ba’yah Abd Kadir, N.; Yusooff, F. A study on the knowledge, attitudes, awareness status and behaviour concerning solid waste management. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 18, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matter, A.; Dietschi, M.; Zurbrügg, C. Improving the informal recycling sector through segregation of waste in the household—The case of Dhaka Bangladesh. Habitat Int. 2013, 38, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxics Link. An Initiative Towards Decentralised Solid Waste Management, Collaborative Efforts of RWA—Defence Colony, New Delhi and Toxics Link (An Environmental NGO); Toxics Link: New Delhi, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J.R. Seeking common ground for people: Livelihoods, governance and waste. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutberlet, J. More inclusive and cleaner cities with waste management co-production: Insights from participatory epistemologies and methods. Habitat Int. 2015, 46, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockson, G.N.K.; Kemausuor, F.; Seassey, R.; Yanful, E. Activities of scavengers and itinerant buyers in Greater Accra, Ghana. Habitat Int. 2013, 39, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colon, M.; Fawcett, B. Community-based household waste management: Lessons learnt from EXNORA’s “zero waste management” scheme in two South Indian cities. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmi, W.S.; Sutton, K. Cairo’s Zabaleen garbage recyclers: Multi-nationals’ takeover and state relocation plans. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 809–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Environment and society: Sustainability, Policy, and the Citizen; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Challcharoenwattana, A.; Pharino, C. Co-Benefits of Household Waste Recycling for Local Community’s Sustainable Waste Management in Thailand. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7417–7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Municipalities | A | B | C | D | Unknown | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Delhi | 296 | 144 | 63 | 16 | 0 | 519 |

| North Delhi | 579 | 291 | 197 | 95 | 176 | 1338 |

| South Delhi | 331 | 290 | 199 | 38 | 16 | 874 |

| New Delhi | 79 | 114 | 88 | 20 | 15 | 316 |

| Total | 1285 | 839 | 547 | 169 | 207 | 3047 |

| Category | Questionnaire Content | Percentage | 2011 Census |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 54 | 53 |

| Female | 46 | 47 | |

| Age Categories | Less than 21 | 9 | 17 |

| 21–40 | 59 | 51 | |

| 41–60 | 27 | 25 | |

| Above 60 | 6 | 8 | |

| Household Size | Less than 3 | 4 | 11 |

| 3–4 | 32 | 38 | |

| 5–8 | 56 | 41 | |

| More than 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Respondent Education | Illiterate | 6 | 15 |

| Literate and Schooling between 5 and 9 years | 20 | 30 | |

| Senior Secondary or Higher Secondary and Some college including diploma | 55 | 32 | |

| Graduate or Post Graduate general or professional | 19 | 23 | |

| Socio-Economic Classification | A (highest category) | 42 | - |

| B | 28 | - | |

| C | 18 | - | |

| D (lowest category) | 6 | - | |

| Not available | 7 | - | |

| Municipality | North Delhi Municipal Corporation | 44 | - |

| South Delhi Municipal Corporation | 27 | - | |

| East Delhi Municipal Corporation | 17 | - | |

| New Delhi Municipal Council | 10 | - | |

| Not available | 2 | - |

| Category | Questionnaire Content | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Segregation | Segregation Rate | 2 |

| Reason for not segregating the waste | Because waste collector mixes segregated waste | 58 |

| Waste storage | Bin inside the house | 75 |

| Reuse a plastic bag and keep inside the house | 19 | |

| Store outside the house by the roadside | 6 | |

| Store in a cement bin outside the house | 0 | |

| Kabariwala | Sell items to Kabariwala 1 | 97 |

| What is sold to Kabariwala? | Newspaper | 43 |

| Magazine | 4 | |

| Cardboard | 3 | |

| Glass bottles | 18 | |

| Dalda tins 2 | 5 | |

| Pet bottles | 4 | |

| Plastic oil cans | 22 | |

| Reasons for selling to Kabariwala? | Convenience | 1 |

| Price | 65 | |

| Household tradition | 1 | |

| Environment | 34 | |

| Waste disposal | Is there any community bin/dhalao in your area (Yes) | 80 |

| Is your community bin cleared on a daily basis (Yes) | 63 | |

| Is roadside open plot dumping practiced in the locality (Yes) | 78 |

| Category | Questionnaire Content | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Doorstep waste collection | Does anyone collect waste from your house (Yes) | 87 |

| Who collects waste from your house? | Municipality | 72 |

| Private Contractor | 6 | |

| Non-Governmental Organization | 2 | |

| Individual person not connected with any organization | 13 | |

| Residents Welfare Association | 1 | |

| I don’t know | 6 | |

| Other | 1 | |

| How frequently is waste collected? | Daily | 87 |

| Alternate days | 4 | |

| Twice a week | 8 | |

| Once a week | 0 | |

| Occasionally | 1 | |

| Payment for doorstep waste collection? | Do you pay for doorstep waste collection (Yes) | 44 |

| To whom do you pay? | Local sweeper | 44 |

| Collector themselves | 29 | |

| Representative of the waste collector | 28 | |

| How much do you pay monthly for doorstep waste collection? | INR 31–50 1 | 59 |

| INR 51–100 | 19 | |

| Less than INR 30 | 22 | |

| Over INR 100 | 0 |

| Factors | Questions | Reliability Coefficient | Percentages of Appropriate Responses (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness to Engage | I am willing to segregate my waste to make recycling more efficient and to safeguard the health of workers. | 0.712 | 74 (Yes) |

| I am ready to accept a lower price for my old paper/plastic/glass products if it is disposed in an environmentally friendly and socially responsible manner. | 80 (Yes) | ||

| I am willing to start composting. | 71 (Yes) | ||

| It is practical for me to live without plastic bags. | 81 (Yes) | ||

| Abstract Knowledge | Do you know the difference between biodegradable and non-biodegradable waste. | 0.674 | 60 (No) |

| Reducing consumption, and therefore waste, is not an option for India at this moment on its path towards economic progress. | 49 (False) | ||

| Burning of waste in a neighborhood is safe as long as it is outside the home. | 58 (False) | ||

| Improper waste management causes pollution. | 95 (Yes) | ||

| Reusing more things is better than buying new things. | 77 (Yes) | ||

| Concrete Knowledge | Are you aware of the condition of landfills in your city. | 0.767 | 31 (Yes) |

| Should waste generators pay based on the type of waste they throw away. | 46 (Yes) | ||

| Should waste generators pay depending on how much they throw away. | 44 (Yes) | ||

| Kabariwalas and wastepickers recycle most municipal solid waste generated. | 98 (True) |

| Categories | Questionnaire Content | Mean Score 2 | Significance 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 3.08 | 0.000 |

| Female | 3.38 | ||

| Age | Less than 21 | 2.94 a | 0.000 |

| 21–40 | 3.18 ab | ||

| 41–60 | 3.31 bc | ||

| Above 60 | 3.58 c | ||

| Socio-Economic Category | A | 3.55 b | 0.000 |

| B | 3.07 a | ||

| C | 3.12 a | ||

| D | 3.79 b |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhawal Mukherji, S.; Sekiyama, M.; Mino, T.; Chaturvedi, B. Resident Knowledge and Willingness to Engage in Waste Management in Delhi, India. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101065

Bhawal Mukherji S, Sekiyama M, Mino T, Chaturvedi B. Resident Knowledge and Willingness to Engage in Waste Management in Delhi, India. Sustainability. 2016; 8(10):1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101065

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhawal Mukherji, Sudipta, Makiko Sekiyama, Takashi Mino, and Bharati Chaturvedi. 2016. "Resident Knowledge and Willingness to Engage in Waste Management in Delhi, India" Sustainability 8, no. 10: 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101065

APA StyleBhawal Mukherji, S., Sekiyama, M., Mino, T., & Chaturvedi, B. (2016). Resident Knowledge and Willingness to Engage in Waste Management in Delhi, India. Sustainability, 8(10), 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101065