Policy Instruments for Eco-Innovation in Asian Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

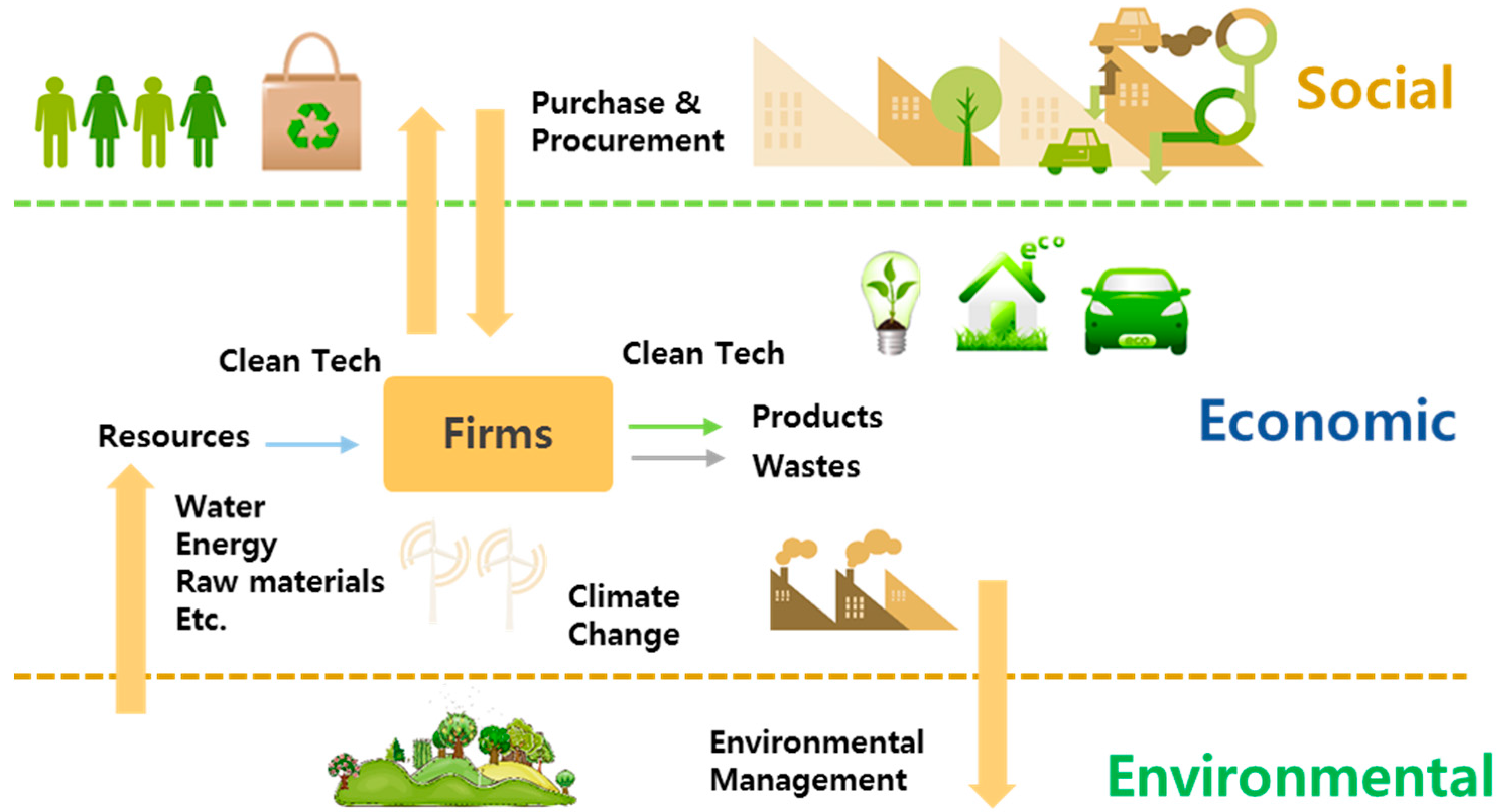

2. Eco-Innovation

2.1. Definition of Eco-Innovation

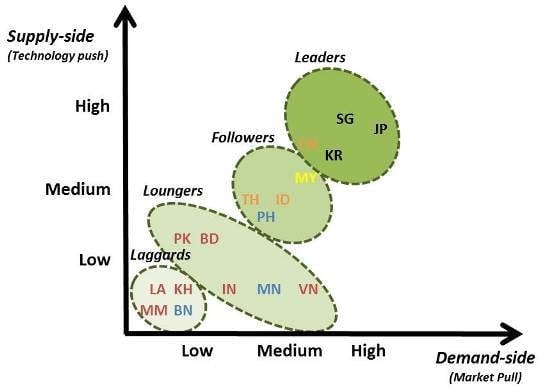

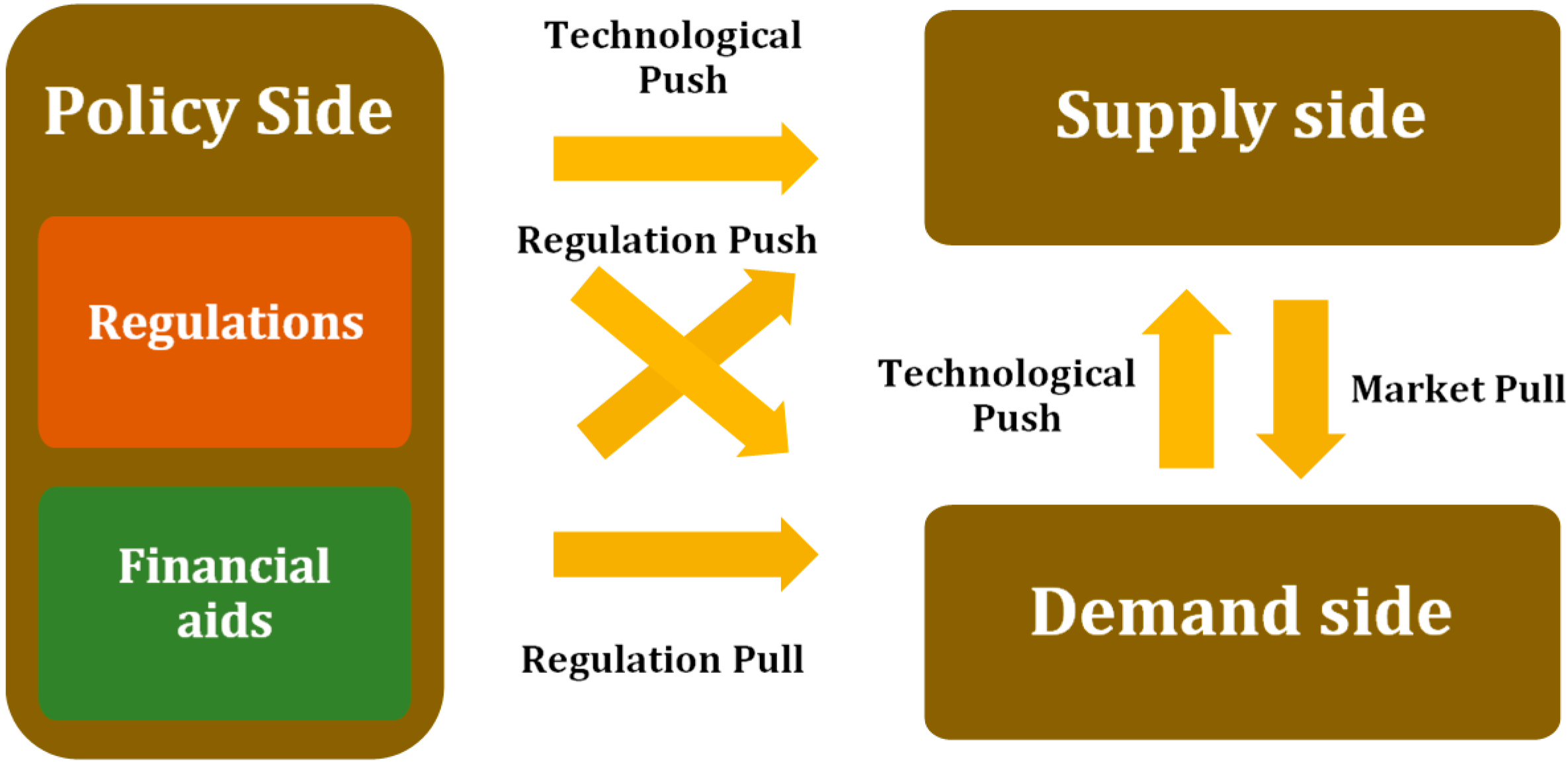

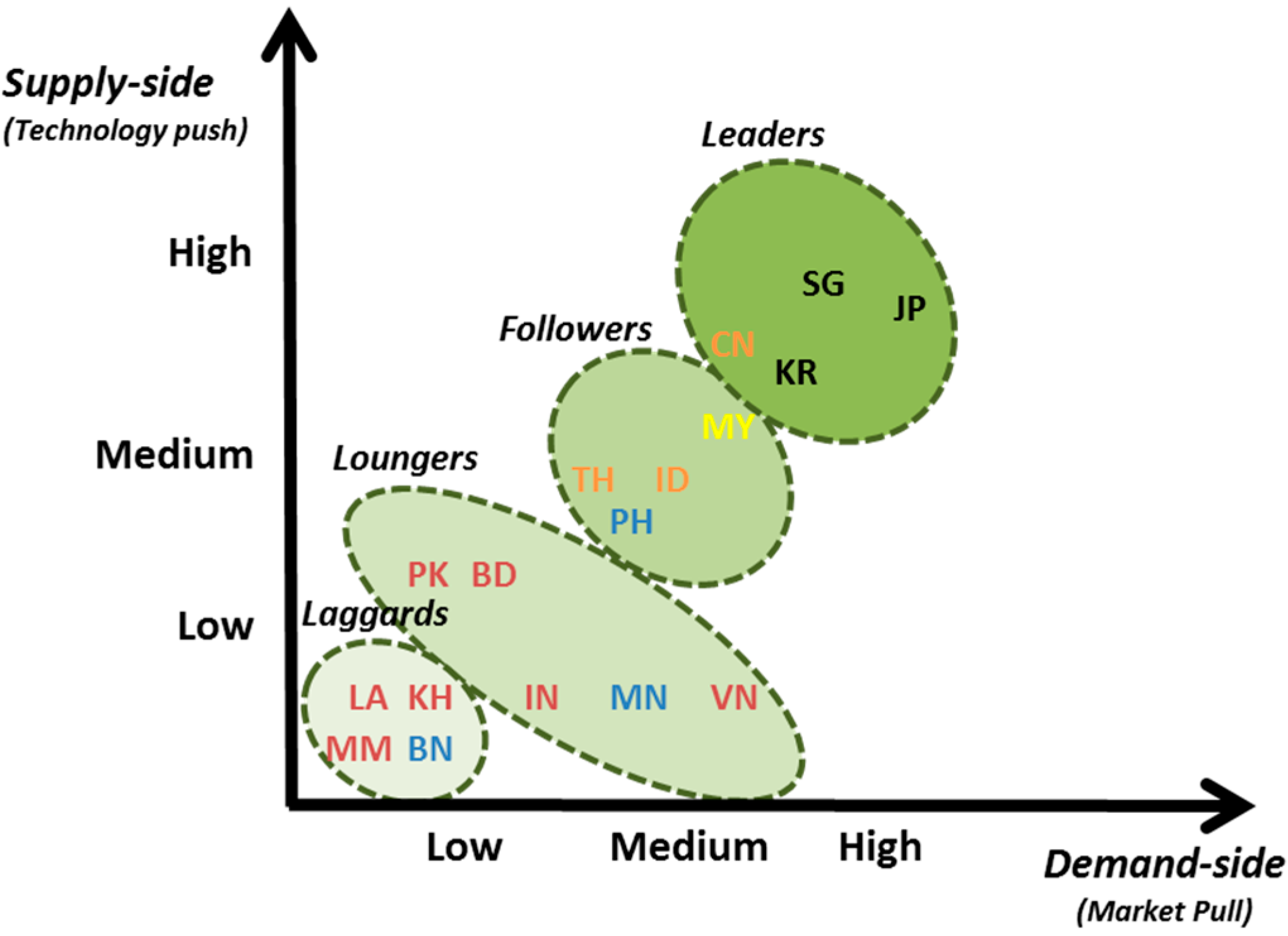

2.2. Determinants of Eco-Innovation

| Elements | Contents |

|---|---|

| Supply | Technological capabilities (knowledge capacities) |

| Appropriation problems and market characteristics | |

| Demand | (Expected) market demand (the demand pull hypothesis) |

| Social awareness of the need for clean production; environmental consciousness and preferences for environmentally friendly products | |

| Institutional and political influences | Environmental policy instruments |

| Institutional structure |

3. Policy Instruments

4. Method

| Stage | Countries |

|---|---|

| 1 | Vietnam, Lao PDR *, India, Pakistan, Cambodia *, Bangladesh *, and Myanmar * |

| 1–2 | Mongolia, Philippines, and Brunei Darussalam |

| 2 | China, Thailand, and Indonesia |

| 2–3 | Malaysia |

| 3 | Singapore, Japan, and Republic of Korea |

| Type | Content |

|---|---|

| Regulatory instruments | Laws, regulations, orders, and decisions |

| Economic instruments | Grants, taxes, and subsidies |

| Informational instruments * | Training, forums, conferences, workshops, and exhibitions |

| Planning instruments | National plans, strategies, programs, actions, and roadmaps |

5. Results

5.1. Planning Instruments: National Plans and Programs

| Economic Stage | Country | National Plan and Strategy | Sector | International Support | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | Eco-Innovation | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |||

| 3 | Singapore | Singapore Green Plan (1992, revised 2012) | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||

| Sustainable Singapore Blueprint 2015 (2009) | o | o | o | - | o | o | ||||

| Maritime Singapore Green Initiative (2011) | - | o | - | - | o | o | ||||

| Japan | Top Runner Program (1998) | - | - | o | - | o | o | |||

| Japan’s Strategy for a Sustainable Society (2007) | o | o | o | o | o | o | 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse, Recycle) Initiative (2005) | |||

| New Growth Strategy (2009-2010) | - | - | o | - | o | - | ||||

| Strategic Energy Plan (2010, 2014) | - | o | o | o | o | - | ||||

| Green Innovation Strategy (2010) | - | - | o | - | o | o | ||||

| Third Science and Technology Basic Plan (2006–2010) | - | - | o | - | o | - | ||||

| Fourth Science and Technology Basic Plan (2011–2015) | - | - | o | - | o | - | ||||

| Republic of Korea | Green Vision 21 1996–2005 (1995) | o | o | - | - | o | o | |||

| National Action Plan for the Implementation of Agenda 21 (1996) | o | o | - | - | o | o | ||||

| Ten-Year National Plan for Energy Technology Development 1997–2006 | - | - | o | - | o | o | ||||

| Ten-Year Basic Plan for the Development and Dissemination of New and Renewable Technologies (2003) | - | - | o | - | o | o | ||||

| First National Energy Master Plan 2008–2030 (2008) | o | - | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Green New Deal (2009–2012) | o | o | o | - | o | o | ||||

| Five-Year Plan for Green Growth 2009–2013 | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Five-Year Plan for Green Growth 2014–2018 | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Green Growth Strategy (2009–2050) | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||||

| 2–3 | Malaysia | 10th Malaysia Plan (2011–2015) | o | o | o | o | o | o | Switch-Asia Project | |

| National Renewable Energy Policy and Action Plan (2009) | - | o | o | o | o | - | ||||

| Green Technology Master Plan 2030 (2013) | o | o | o | o | o | - | ||||

| National Strategic Plan for Solid Waste Management (2005) | - | o | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Master Plan on National Waste Minimization (2006) | - | o | - | - | - | - | 3R (supported by Japan’s International Cooperation Agency) | |||

| 2 | China | China’s Agenda 21 (1994) | o | o | o | o | o | o | Switch-Asia Project | |

| Energy Saving and New Energy Vehicle Development Plan 2011–2020 (2009) | - | - | - | o | o | - | ||||

| Thailand | Agenda 21 (1993) | o | o | o | - | o | o | Switch-Asia Project | ||

| Plan for Enhancement and Conservation of National Environmental Quality (1997) | o | - | - | - | o | - | ||||

| Thailand Climate Change Master Plan 2013–2050 (2012) | o | - | o | - | o | o | ||||

| National Green Procurement Plan (2008) | - | - | - | o | - | - | ||||

| National Science Technology and Innovation Policy 2012–2021 (2011) | o | - | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Thailand 20-Year Energy Efficiency Development Plan (2011–2030) | o | - | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Green Growth Strategic Plan 2013–2018 (2013) | o | o | o | - | o | o | ||||

| Indonesia | Indonesia Agenda 21 (1992) | o | - | - | - | o | o | Indonesia-Singapore Environmental Partnership (ISEP) (2002) | ||

| National Action Plan on GHG Emission Reduction (2010) | o | o | o | - | - | o | ||||

| National Energy Policy (2006) | - | - | o | o | o | - | APEC Policy Partnership on Science, Technology and Innovation (PPSTI) | |||

| Indonesia’s Energy Vision 25/25 (2011) | - | o | o | o | o | o | Eco-Industry Program (2009) Green Investment Program (2010–2011) Switch-Asia Project GIZ Forests and Climate Change Program (FORCLIME) (2008–2010) | |||

| 1–2 | Mongolia | Mongolian National Sustainable Development Agenda (2005) | o | o | o | o | o | o | Switch-Asia Project | |

| Philippines | Philippines Agenda 21 (1996) | o | o | - | - | o | - | Switch-Asia Project | ||

| Philippine Development Plan 2011–2016 (2011) | o | o | o | - | o | o | ||||

| National Climate Change Action Plan 2011–2028 (2011) | o | o | - | - | o | o | ||||

| Philippine Energy Plan 2008–2030 (2008) | - | - | o | - | o | o | ||||

| National Action Plan on Sustainable Public Procurement 2010–2012 (2010) | - | - | - | o | - | - | ||||

| Brunei Darussalam | Wawasan Brunei 2035 (Vision Brunei 2035) | o | - | - | - | o | - | |||

| 1 | Vietnam | Socio-economic Development Strategy for 1991–2000 | o | o | - | - | o | - | Sustainable Product Innovation Project (SPIN) VCL (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos) (2010–2013) Vietnam Energy Efficiency and Cleaner Production (EECP) Financing Program (2010–2011) Vietnam Energy Efficiency Program (VNEEP) (2006) Vietnam Clean Production and Energy Efficiency Project (2011–2016) | |

| Five Year Socio-economic Development Plan 2006-2010 | o | o | - | - | o | - | ||||

| The Socio-Economic Development Strategy for 2011–2020 | o | o | - | - | o | o | ||||

| Strategic Orientation for Sustainable Development (Vietnam Agenda 21) (2004) | o | o | o | - | o | o | ||||

| Climate Change Adaptation (2011) | o | - | - | - | o | o | ||||

| National Energy Master Plan (2007) | - | - | o | o | o | - | ||||

| National Green Growth Strategy for the Period 2011–2020 with a Vision to 2050 (2013) | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Lao PDR | Strategic Framework for National Sustainable Development Strategy (2008) | o | o | o | - | o | o | Sustainable Product Innovation Project (SPIN) VCL (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos) (2010–2013) | ||

| Ecotourism Strategy and Action Plan 2005–2010 (2004) | o | - | - | o | - | - | ||||

| Sustainable Transport Strategy 2020 (2005) | - | - | - | - | o | - | ||||

| Renewable Energy Strategy to 2025 (2011) | - | - | o | - | o | o | ||||

| India | Ninth Five-year Plan with SD recognized (1997-2002) | o | o | o | o | o | o | Switch-Asia Project | ||

| Science, Technology and Innovation Policy (2013) | - | - | - | - | o | o | ||||

| National Biofuel Policy (2008) | - | - | o | o | o | - | ||||

| Strategic Plan for New and Renewable Energy Sector (2011–2017) | - | - | o | o | o | - | ||||

| Pakistan | Agenda 21 | o | - | - | - | o | o | Switch-Asia Project | ||

| National Sustainable Development Strategy (2012) | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy (2011) | o | - | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Pakistan Energy Vision 2035 (2014) | - | - | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Cambodia | National Strategic Development Plan 2009 - 2013 (2009) | o | o | o | o | o | o | Sustainable Product Innovation Project (SPIN) VCL (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos) (2010–2013) | ||

| National Green Growth Roadmap (2010) | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||||

| Bangladesh | National Sustainable Development Strategy (2009) | o | o | o | - | o | o | Switch-Asia Project | ||

| Bangladesh Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (BCCSAP) (2008) | o | - | o | - | o | o | ||||

| Myanmar | Myanmar Agenda 21 (1997) | o | o | o | - | - | - | Switch-Asia Project | ||

| National Sustainable Development Strategy (2009) | o | o | o | o | o | o | ||||

5.2. Regulatory and Economic Instruments

| Economic Stage | Country | Environmental Protection and Management | Waste | (Renewable) Energy | Purchase/Procurement | Clean Technology | Climate Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Singapore | Environmental Protection and Management Act (1999, revised 2002) Environmental Pollution Control Act 1999 | Hazardous Waste Act (1998) | Energy Conservation Act (2012) | - | Agency for Science, Technology and Research Act (1990, revised 2002) | - |

| Japan | Basic Law for Environmental Pollution Control (1967) Nature Conservation Law (1972) Basic Environmental Law (1993) | Waste Management and Public Cleansing Law (1970) | Renewable Portfolio Standard (2003) | Green Purchasing Law (2000) Act on Special Measures Concerning Procurement of Renewable Electric Energy Operators of Electric Utilities (2012) Act on Purchase of Renewable Energy Sourced Electricity by Electric Utilities (2012) | Science and Technology Basic Law (1995) | Act on Promotion of Global Warming Countermeasures (1998) Law Concerning the Promotion of Contracts considering Reduction of GHG Emissions by the State and Other Entities (Green Contract Law) (2007) | |

| Republic of Korea | Natural Environment Conservation Act (1991) Environment Health Act (2008) | Waste Control Act (1986) | Act on the Promotion of the Development, Use and Diffusion of New and Renewable energy (2004) Basic Law on Low Carbon Green Energy (2010) | Act on Promotion of Purchase of Green Products (2005) Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) (2012) Renewable Energy Certificates (REC) (2013) | Development of and Support for Environmental Technology Act (2000, revised 2008) | Act on the Allocation and Trading of Greenhouse-Gas Emission Permits (2012) Framework Act and Low Carbon and Green Growth (2010) | |

| 2–3 | Malaysia | Environmental Quality Act (1974) | Solid Waste and Public Cleansing Management Act (2007) | Renewable Energy Act (2011) Sustainable Energy Development Authority Act (2011) Malaysia Biofuels Industry Act (2007) Efficient Management of Electrical Energy Regulations (2008) | - | Environmental Quality Act (1974, revised 2012) | - |

| 2 | China | Environmental Protection Law (1989) | Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention and Control of Environmental Pollution by Solid Waste (1995) | Renewable Energy Law (2005) Energy Conservation Law (2007) | Government Procurement Law (GPL) (2003) Cleaner Production Promotion Law (2002 issued; 2012 revised) | Clean Production Promotion Law (2003, revised 2012) China Science and Technology Promotion Law (2007) | Law of the People's Republic of China on the Desert Prevention and Transformation (2001)) |

| Thailand | Enhancement and Conservation of National Environmental Quality Act (NEQA) (1975, revised 1992) Thailand Constitution (1997) | - | Energy Conservation Promotion Act (1992, revision 2007) | - | Enhancement and Conservation of National Environmental Quality Act (NEQA) (1975, revised 1992) | - | |

| Indonesia | Act No. 4 (1982, revised 1997) Law No. 32/2009 on Environmental Protection and Management (2009) | Waste Management Law No. 18 | Geothermal Law No. 27/2003 (2003) MEMR decision No. 2/2004 (2004) Presidential Regulation No. 5/2006 (2006) Governmental Regulation No. 70/2009 (2009) | - | Law of the Republic of Indonesia No. 27 (2003) | Presidential Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia No 61 (2011) | |

| 1–2 | Mongolia | Environmental Protection Law (1995, revised 2007) | Law on Prohibition and Export of Hazardous Waste (2000) Law on Household and Industrial Waste Management (2003) Law on Payment of Package and Case Imported Goods (2005) | Energy Law of Mongolia (2001) Renewable Energy Law (2007) | - | Law on Technology Transfers (1998) | - |

| Philippines | Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act (2001) | Ecological Solid Waste Management Act (2000) | Biofuels Act (2007) Renewable Energy Act (2008) | Executive Order No. 301(1987, revised 2004) | Philippines Technology Transfer Act (2009) Philippines Clean Air Act (1999) | Climate Change Act of 2009 | |

| Brunei Darussalam | Wildlife Protection Law (1981) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 1 | Vietnam | Environmental Protection Law (2005) | Regulation of Management of Hazardous Waste (1999) National Technical Regulation on Hazardous Waste Threshold (2009) | Law on Energy Efficiency No: 50/2010/QH12 (2010) | - | Law on Science and Technology (No. 21/2000/QH10) (2000) | Decision No. 158; QD-TTg Approving the National Target Program on Response to Climate Change (2008) |

| Lao PDR | Environmental Protection Law (1999) | - | - | - | Environmental Protection Law (1999) | - | |

| India | EIA Notification for Environmental Clearance (2006) National Green Tribunal Act (NGT) (2010) National Environmental Assessment and Monitoring Authority (2014) | Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act (1981) Recycled Plastics Manufacture and Usage Rules (1999) | Energy Conservation Act (2001, revised 2010) | - | Motor Vehicles Act (1988) Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act (1981) | - | |

| Pakistan | Pakistan Environmental Protection Act (1997) | Hazardous Substances Rules (1999) | Renewable Energy Technologies Act (2010) | - | National Clean Air Act | - | |

| Cambodia | Law on Environmental Protection and Natural Resource Management (1996) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Bangladesh | Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act (1995) | Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act and Rules (1995) | Bangladesh Water and Power Development Boards Order (1972) | - | Bangladesh Water and Power Development Boards Order (1972) | Climate Change Trust Fund Act (2010) | |

| Myanmar | Environmental Conservation Law (2012) Environmental Conservation Rules (2014) | - | - | - | Science and Technology Development Law (1994) | - |

| Economic Stage | Country | Title of Economic Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Singapore | Innovation for Environmental Sustainability (IES) Fund (2001) |

| 3R Fund (2009) | ||

| Energy Efficiency Improvement Assistance Scheme (EASe) (2005) | ||

| Grant for Energy Efficient Technologies (GREET) | ||

| One-Year Accelerated Depreciation Allowance for Energy Efficient Equipment and Technology (ADAS) | ||

| Design for Efficiency Scheme (DfE) (2008) | ||

| Clean Energy Research and Testbedding Program (CERT) (2007) | ||

| Energy Research Development Fund (ERDF) (2008) | ||

| Pilot Building Retrofit Energy Efficiency Financing (BREEF) Scheme (2011) | ||

| Green Mark Incentive Scheme for Existing Buildings (GMIS-EB) (2015) | ||

| Green Mark Incentive Scheme—Design Prototype (GMIS-DP) (2015) | ||

| Sustainable Construction Capability Development Fund (SC Fund) (2010) | ||

| Water Efficiency Fund (WEF) (2007) | ||

| Clean Development Mechanism Documentation Grant (2008) | ||

| Tax Incentives for Renewable Energy (2014) | ||

| Japan | Japan Fund for Global Environment (JFGE) (1993) | |

| JPMorgan Japan Technology Fund (2005) | ||

| Japan’s Voluntary Emissions Trading Scheme (JVETS) (2005) | ||

| Global Environment Research Fund (2010) | ||

| Environment Technology Development Fund (2010) | ||

| Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (about stabling a sound material-cycle society) (2011) | ||

| Green Fund (2013) | ||

| Green Vehicle Purchasing Promotion Program (2009) | ||

| Eco-Car Tax Breaks (2009) | ||

| Feed-in-Tariff Scheme for Renewable Energy (2009) | ||

| Tax for Climate Change Mitigation (2012) | ||

| Funding Program for World-Leading Innovative R&D on Science and Technology (FIRST Program) (2009) | ||

| Republic of Korea | Environmental Improvement Fund (1992) | |

| 21st Century Frontier R&D Program (1999) | ||

| Eco-Technopia 21 Project (2001) | ||

| Environmental Venture Fund (2001) | ||

| Environmental Industry Promotion Fund (2009) | ||

| Recycling Industry Promoting Loan (2012) | ||

| Fiscal Incentives for Renewable Energy (2009) | ||

| Feed-in-Tariff Scheme for Renewable Energy (replaced by the RPS) (2006) | ||

| 2–3 | Malaysia | Incentives for Building obtaining GBI (Green Building Index) Certificate (2009) |

| Green Technology Financing Scheme (2010) | ||

| Renewable Energy Fund (2011) | ||

| Feed in Tariff for Renewable Energy (2011) | ||

| GEF UNIDO Global Clean Tech Program for SMEs (2013) | ||

| Malaysia-Japan Clean Tech Fund (2013) | ||

| Green Investment Tax Allowance (GITA) (2014) | ||

| 2 | China | Golden Sun Program (2009) |

| Tax Rebate for Wind Energy Producers (2013) | ||

| Renewable Energy Development Fund (2008) | ||

| China CDM Fund (2006) | ||

| Green Carbon Fund (2008) | ||

| Mobilizing financing from National New Products Program & National Key Technologies R&D Program (1986) | ||

| National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (1997) | ||

| National Hi-tech R&D Program (863 Program) (1986) | ||

| Innovation Fund for Technology-based Firms (1986) | ||

| Feed-in-Tariff Scheme for Renewable Energy (2011) | ||

| Thailand | Energy Conservation Promotion Fund (ECPF) (1993) | |

| Power Development Fund (2010) | ||

| Clean Technology Fund (2009) | ||

| Feed-in-Tariff Scheme (2006) | ||

| Fiscal incentives for sale of carbon credits (2009) | ||

| Indonesia | Eco-industry Program (2009) | |

| Green Investment Program (2011) | ||

| Environmental Soft Loans(for SMEs) (2008) | ||

| The Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund (2010) | ||

| Feed-in Tariff Scheme for Renewable Energy (2012) | ||

| 1–2 | Mongolia | GEF Small Grants Program (2002) |

| Feed-in-Tariff Range for Renewable Energy (2007) | ||

| Philippines | Philippines Sustainable Energy Finance Program (2008) | |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship Enhancement and Development Program (SEED) (2004) | ||

| Clean Technology Fund Investment Plan for the Philippines (2012) | ||

| Fiscal incentives for Renewable Energy (2008) | ||

| Feed-in-Tariff Scheme (2012) | ||

| Brunei Darussalam | - | |

| 1 | Vietnam | Vietnam Energy Efficiency and Cleaner Production (EECP) Financing Program (2010) |

| Feed-in-Tariff for Renewable Energy (2011) | ||

| Fiscal Incentives for Renewable Energy (2008) | ||

| Lao PDR | - | |

| India | Feed-in-Tariff scheme for renewable energy (2010) | |

| Pakistan | Provincial Sustainable Development Funds (2011) | |

| Cambodia | Cambodia Climate Change Alliance (CCCA) Trust Fund (2011) | |

| Bangladesh | Clean Technology Fund (2008) | |

| Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund (2010) | ||

| Myanmar | - |

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm (accessed on 11 September 2015).

- OECD. Better Policies to Support Eco-Innovation; OECD Studies on Environmental Innovation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cuerva, M.C.; Triguero-Cano, Á.; Córcoles, D. Drivers of green and non-green innovation: Empirical evidence in Low-Tech SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 68, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.; Trifilova, A. Green technology and eco-innovation: Seven case-studies from a Russian manufacturing context. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2010, 21, 910–929. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, J. Consumer Eco-Innovation Adoption: Assessing Attitudinal Factors and Perceived Product Characteristics. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 210, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolny, W. Determinants of innovation behaviour and investment estimates for West-German manufacturing firms. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2003, 12, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletzan-Slamanig, D.; Reinstaller, A.; Unterlass, F.; Stadler, I.; Leflaive, X. Assessment of ETAP Roadmaps with Regard to Their Eco-Innovation Potential; Report commissioned by the OECD Environmental Directorate to the Austrian Institute of Economic Research (WIFO): Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Triguero, A.; Moreno-Mondéjar, L.; Davia, M.A. Drivers of different types of eco-innovation in European SMEs. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 92, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, S.P.; Natarajan, J.; Gunasekaran, A.; Subramanian, N. Influence of eco-innovation on Indian manufacturing sector sustainable performance. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2014, 21, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. The Driver of Green Innovation and Green Image—Green Core Competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.; Shiu, E.C. Validation of a proposed instrument for measuring eco-innovation: An implementation perspective. Technovation 2012, 32, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, J.; Qiao, Y.; Shi, L. Effects of eco-innovation typology on its performance: Empirical evidence from Chinese enterprises. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2014, 34, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Colicchia, C.; Cozzolino, A.; Christopher, M. The logistics service providers in eco-efficiency innovation: An empirical study. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 18, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.J.; Yang, C.; Sheu, C. The link between eco-innovation and business performance: A Taiwanese industry context. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierzchula, W.; Bakker, S.; Maat, K.; van Wee, B. Technological diversity of emerging eco-innovations: A case study of the automobile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 37, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.; Lee, K.; Ha, S. Eco-efficiency for pollution prevention in small to medium-sized enterprises—A case from South Korea. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM), A Statistical Portrait; Eurostat: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion; IEA: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. A study on the relationship between corporate’s environmental innovation and environmental policy. Korean J. Public Adm. 2002, 40, 159–188. [Google Scholar]

- International Green Purchasing Network. Green Purchasing: The New Growth Frontier; International Green Purchasing Network: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bleischwitz, R.; Schmidt-Bleek, F.; Giljum, S.; Kuhndt, M. Eco-Innvoation-Putting the EU on the Path to a Resource and Energy Efficient Economy; Wuppertal Institute: Wuppertal, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rennings, K. Redefining innovation—Eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Pontoglio, S. The innovation effects of environmental policy instruments—A typical case of the blind men and the elephant? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.N. Promoting Eco-innovations to Leverage Sustainable Development of Eco-industry and Green Growth. Int. J. Ecosyst. Ecol. Sci. 2013, 3, 171–224. [Google Scholar]

- Fussler, C.; James, P. Driving Eco-Innovation—A Survey; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R.; Arundel, A. Survey Indicators for Environmental Innovation; The STEP Group: Oslo, Norway, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Little, A.D. Study for the Conception of a Programme to Increase Material Efficiency in Small and Medium Sized Enterprises; Wuppertal Institute: Wuppertal, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Charter, M.; Clark, T. Sustainable Innovation; The Center for Sustainable Design: Farnham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Sustainable Manufacturing and Eco-Innovation. Framework, Practices and Measurement; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Sustainable Manufacturing and Eco-Innovation: Towards a Green Economy; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The Eco-Innovation Observatory (EIO): Methodological Report. Available online: http://www.eco-innovation.eu (accessed on 11 September 2015).

- OECD; Eurostat. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, 3rd ed.; OECD: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R. Environmental Policy and Technological Change; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Frondel, M.; Horbarch, J.; Rennings, K. End-of-pipe or cleaner production? An empirical comparison of environmental innovation decisions across OECD countries. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, P.; Kesidou, E. Stimulating different types of eco-innovation in the UK: Government policies and firm motivations. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkinton, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jänicke, M. Ecological modernization: New perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Frijns, J.; Phuong, P.T.; Mol, A.P. Developing countries: Ecological modernisation theory and industrialising economies: The case of Viet Nam. Environ. Polit. 2000, 9, 257–292. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A.P. Environment and modernity in transitional China: Frontiers of ecological modernization. Dev. Chang. 2006, 37, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, J. Determinants of environmental innovation—New evidence from German panel data sources. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehfeld, K.-M.; Rennings, K.; Ziegler, A. Integrated product policy and environmental product innovations: An empirical analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavitt, K. Sectoral patterns of technical change: Towards a taxonomy and a theory. Res. Policy 1984, 13, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.; Newell, R.G. Accelerating Energy Innovation: Lessons from Multiple Sectors; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, R.G. The role of markets and policies in delivering innovation for climate change mitigation. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2010, 26, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Foxon, T. Eco-Innovation from an Innovation Dynamics Perspective; UNU-MERIT: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kammerer, D. The effects of customer benefit and regulation on environmental product innvation: Empirical evidence from appliance manufacturers in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, J.; Ryan, G. Regulation and firm perception, eco-innovation and firm performance. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 421–441. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Eco-Innovation Policies in the Republic of Korea; OECD: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vedung, E. Policy instruments: Typologies and theories. In Carrots, Sticks and Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Bemelmans-Videc, M.L., Rist, R.C., Vedung, E.O., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: London, UK, 1998; pp. 21–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bemelmans-Videc, M.L.; Rist, R.C.; Vedung, E. Carrots, Sticks and Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Transaction Publishers: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruijn, H.A.; Hufen, H.A.M. The traditional approach to policy instruments. In Public Policy Instruments: Evaluating the Tools of Public Administration; Guy, P.B., van Nispen, F.K.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Krott, M. Forest Policy Analysis; Peter Lang: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M. Media Discourse in Forest Communication: The Issue of Forest Conservation in the Korean and global Media; Cuvillier: Göttingen, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire, D. The stick: Regulation as a tool of government. In Carrots, Sticks and Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Bemelmans-Videc, M.L., Rist, R.C., Vedung, E.O., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: London, UK, 1998; pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Statistical Division. Glossary of Environment Statistics, Studies in Methods; Series F, No. 67; United Nations Pubns: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krumland, D. Beitrag der Medien zum Politischen Erfolg: Forstwirtschaft und Naturschutz im Politikfeld Wald; Peter Lang: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H. The strategy concept I: Five Ps for strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1987, 30, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEF. The Global Competitiveness Report; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Russel, T. Introduction. In Greener Purchasing: Opportunities and Innvoations; Russel, T., Ed.; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2004/18/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 31 march 2004 on the Coordication of Procedures for the Award of Public Works Contracts, Public Supply Contracts and Public Service Contracs; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Doberstein, B. Greening government procurement in developing countries: Building capacity in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osamu, K. The role of standards: The Japanese Top Runner Program for end-use efficiency. Historical case studies of enegy technology innovation. In Chapter 24, The Global Energy Assessment; Grubler, A., Aguayo, F., Gallagher, K.S., Hekkert, M., Jiang, K., Mytelka, L., Neij, L., Nemet, G.C.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Japan. Becoming a Leading Environmental Nationa in the 21th Century: Japan’s Strategy for a Sustainable Society; Cabinet Meeting Decision: Tokyo, Japan, 2007.

- Regional 3R forum in Asia and the Pacific. Ha Noi 3R Declaration. Available online: http://www.env.go.jp/recycle/3r/en/declaration/hanoi-declaration.html (accessed on 9 September 2015).

- SWITCHASIA. SWITCH-Asia Grant Projects. Available online: http://www.switch-asia.eu/programme/facts-and-figures/ (accessed on 9 September 2015).

- EU Switch-Asia Programme. Available online: http://archive.switch-asia.eu/switch-asia-projects/project-impact/projects-on-designing-for-sustainability/product-innovation.html (accessed on 9 September 2015).

- Del Río González, P. The empirical analysis of the determinants for environmental technological change: A research agenda. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 861–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.G. Feed-in tariff vs. renewable portfolio standard: An empirical test their relative effectiveness in promoting wing capacity development. Energy Policy 2012, 42, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maplecroft. Climate Change and Environmental Risk Atlas 2015; Maplecroft: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Cabon Portal. China Green Carbon Fund—China Forest Carbon Sink. Available online: http://www.forestcarbonportal.com/project/china-green-carbon-fund (accessed on 9 September 2015).

- BRILL. China’s Green Climate Fund: Innovation and Experience A Case Study of the China Green Carbon Foundation. Available online: http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/chinese-research-perspectives-online/chapter-10-chinas-green-climate-fund-innovation-and-experience-a-case-study-of-the-china-green-carbon-foundation-wang_9789004274631_010 (accessed on 9 September 2015).

- Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund: An innovative Governance Framework. Available online: http://cleancookstoves.org/resources/106.html (accessed on 9 September 2015).

- KPMG. The KPMG Green Tax Index 2013: An Exploration of Green Tax Incentives and Penalties; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Overview of the Republic of Korea’s National Strategy for Green Growth; UNEP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Botta, E.; Kozluk, T. Measuring Environmental Policy Stringency in OECD Countries. A Composite Index Approach; OECD Economics Department Working Papers: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Schneider, M.; Griesshaber, T.; Hoffmann, V.H. The impact of technology-push and demand-pull policies on technical change-Does the locus of policies matter? Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1296–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Pujol, A.; Castano, L. Green Public Procurement in the Asia Pacific Region: Challenges and Opportunities for Green Growth and Trade. Available online: http://www.amphos21.com/a21Admin/redesSociales/2013_cti_GPP-rpt.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2015).

- Triguero, A.; Moreno-Mondéjar, L.; Davia, M.A. Leaders and Laggards in Environmental Innovation: An Empirical Analysis of SMEs in Europe. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.M.L. The Developmental State in Ecological Modernization and the Politics of Environmental Framings: The Case of Singapore and Implications for East Asia. Nat. Cult. 2012, 7, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, E.K.; Park, M.S.; Roh, T.W.; Han, K.J. Policy Instruments for Eco-Innovation in Asian Countries. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12586-12614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70912586

Jang EK, Park MS, Roh TW, Han KJ. Policy Instruments for Eco-Innovation in Asian Countries. Sustainability. 2015; 7(9):12586-12614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70912586

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Eun Kyung, Mi Sun Park, Tae Woo Roh, and Ki Joo Han. 2015. "Policy Instruments for Eco-Innovation in Asian Countries" Sustainability 7, no. 9: 12586-12614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70912586

APA StyleJang, E. K., Park, M. S., Roh, T. W., & Han, K. J. (2015). Policy Instruments for Eco-Innovation in Asian Countries. Sustainability, 7(9), 12586-12614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70912586