1. Introduction

The 21st century’s economy will be urban and green. The urban transition is advancing globally, albeit unsustainably [

1,

2]. The green economy transition is in its infancy. Yet, like other revolutionary socio-technical transitions before it, there are irrepressible sets of push and pull factors massing that can trigger transformative change. The push factors are those capable of delivering innovation. New technologies are among these as well as associated business strategies and practices and government policies and programs that all need to shift towards facilitating this new economy. The pull factors are also clear and relate, among others, to the challenge of creating sustainable and resilient built environments capable of functioning within the ecosystem limits of a single planet subject to climate change and forecast to be home to 9 billion people by 2050 [

3,

4].

This study represents a first attempt within Australia to explore the critical connections that exist between cities and the built environment industries that plan and manage them. Particular focus is on the extent to which these industries are operating in a manner that can deliver much needed sustainable regenerative urban development in the 21st century and contribute to the emergence of a green economy more broadly. It is based on a 2013 survey of 173 senior managers in both private and public sector built environment organizations with membership in national industry associations with acknowledged sustainability objectives.

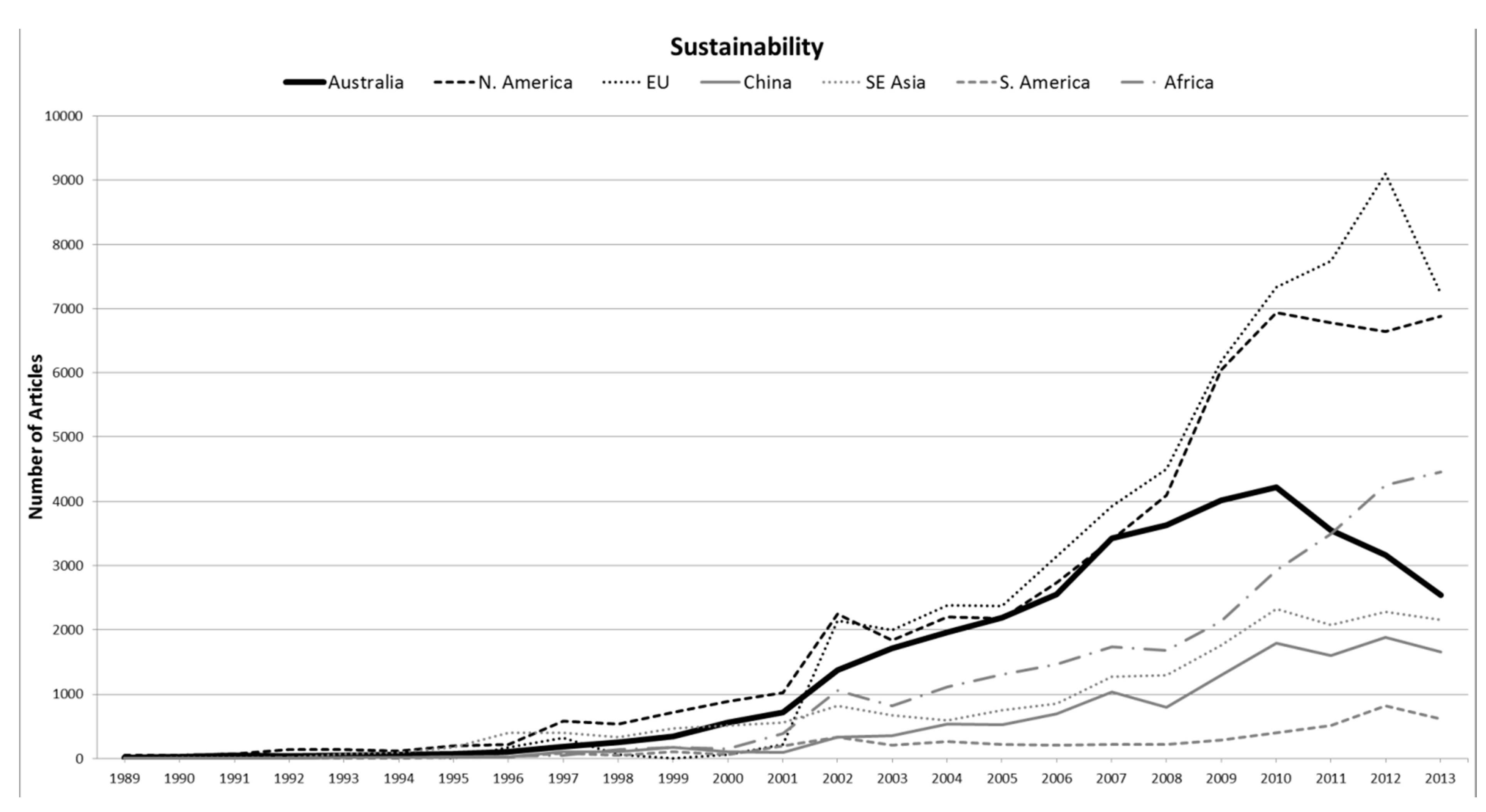

Cities will be critical to sustainable urban development in the 21st century. A transition to sustainable urban development will, however, require a socio-technical transformation of a scale and complexity similar to that of the industrial revolution. The first created a factor of 20 fold increase in productivity. A green revolution will require a further increase by at least a factor of 4 or 5 which means that levels of wealth could double while cutting resource use by 50% or even 80% as suggested and illustrated by Von Weisacker

et al. [

5]. The second, post-industrial revolution is centered on sustainable development as initially articulated by the United Nations [

6,

7] and by much scholarship and public discussion over subsequent decades (see

Figure 1). The graph depicts the volume of articles using the term “sustainability” that were published annually since the Brundtland Report using the search engine Factiva, an on-line tool that aggregates searchable content from over 10,000 licensed sources such as newspapers, journals, magazines, TV and radio transcripts and newswires worldwide, covering most languages.

Sustainability focuses on the need to ensure that human activities and the systems within which they operate (e.g., our human settlements and their populations) can continue into the future—within the earth’s planetary boundaries [

8].

Figure 1.

Trajectories of counts of the term “sustainability” in print. (Source: derived from [

9] using key word “sustainability”.)

Figure 1.

Trajectories of counts of the term “sustainability” in print. (Source: derived from [

9] using key word “sustainability”.)

The progressively growing interest in the subject of sustainability, especially in those developed societies that have the human, social and financial capital to implement transformative change has somewhat stalled though they remain the main source of green products and services. The Global Financial Crisis in North America in 2007–2008 has had knock-on effects globally, with European governments in particular having additional sovereign risk challenges that diminished fiscal support for investment in innovative (longer term) sustainable production and consumption programs in favor of those deemed “shovel-ready” (and job-saving). During this period, many government departments with responsibility for metropolitan planning and development replaced “sustainability” with “livability” or “productivity” as their principal objective, given their clear economic connection to the attraction of international investment and skilled labor… both of which are highly mobile in the 21st century and focused on cities. Cities in North America, Australia and New Zealand and, to a lesser extent, Europe achieve their livability and productivity rankings as a result of their high levels of resource consumption and greenhouse gas emissions [

1] though decoupling of wealth from fossil fuels is now progressing [

10]. Cities in developing countries such as China are also aspiring to create more livable built environments as they rapidly urbanize with substantial ecological footprints in fast growing cities such as Beijing and Shanghai; however, they too are beginning to decouple like those in developed countries [

10].

The principal global challenges are threefold. First, we live in a carbon constrained world which is witnessing increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the earth’s atmosphere capable of triggering climate change of a scale which could take centuries to reverse [

11,

12]. How we generate and consume energy is central to this issue. Second, we live in a resource constrained world where peak oil, water shortages, decline in agricultural land and loss of biodiversity are indications that our harvesting of the earth’s natural resources is now occurring at a rate which is exceeding replacement rate [

13,

14]. Our patterns of consumption of housing, travel, water and manufactured products are central to this issue [

15]. Population growth—forecast to reach nine billion by 2050—when coupled with per capita consumption defines the magnitude of the sustainability challenge. The task of transition from unsustainable levels of consumption is a challenge for the citizens of developed countries in North America, Western Europe and Australia that have ecological footprints three to four times the global average. Concerns about the environmental impacts of consumption have been registered in the OECD [

16] with forecasts that consumption pressure is expected to intensify significantly by 2030. Forecasts have been advanced of major economic and social disruption or collapse associated with continued business as usual operations by industries, governments and communities [

17] unless there is radical change. Third, we live in a world of increasingly concentrated populations, with the world’s 9 billion-population forecast to be 70% urban by 2050, though this remains a question as to whether it helps or hinders the reduction in footprint [

10].

The 21st century sustainability challenge will focus on cities, their future mode of development and redevelopment and their resilience to a mix of exogenous and endogenous forces now in play. In developed societies these have been recently catalogued [

18]. The exogenous factors mirror those listed above: resource constraints (land, water, raw materials, oil); climate change (and its link to sea level rise and its impact on urban infrastructure; increased temperatures and changes to rainfall frequency and intensity—flooding in some locales, drought and heat extremes and megafires in others); bio-security (including pandemics) and financial uncertainty. The endogenous factors reflect the contemporary context and dynamics of each individual city: the quality of its existing buildings and infrastructure; its human and social capital and levels of social and spatial disadvantage; its governance structures; its urban environmental quality and the nature and trajectory of its economic base. In this context, a wide range of international, national and metropolitan studies of city performance continue to catalogue deficiencies across the spectrum of human settlement indicators associated with environmental quality and metabolism, economic productivity and competitiveness, liveability and social inclusion—all of which are inter-related dimensions that characterise the current state of sustainability of urban development [

19].

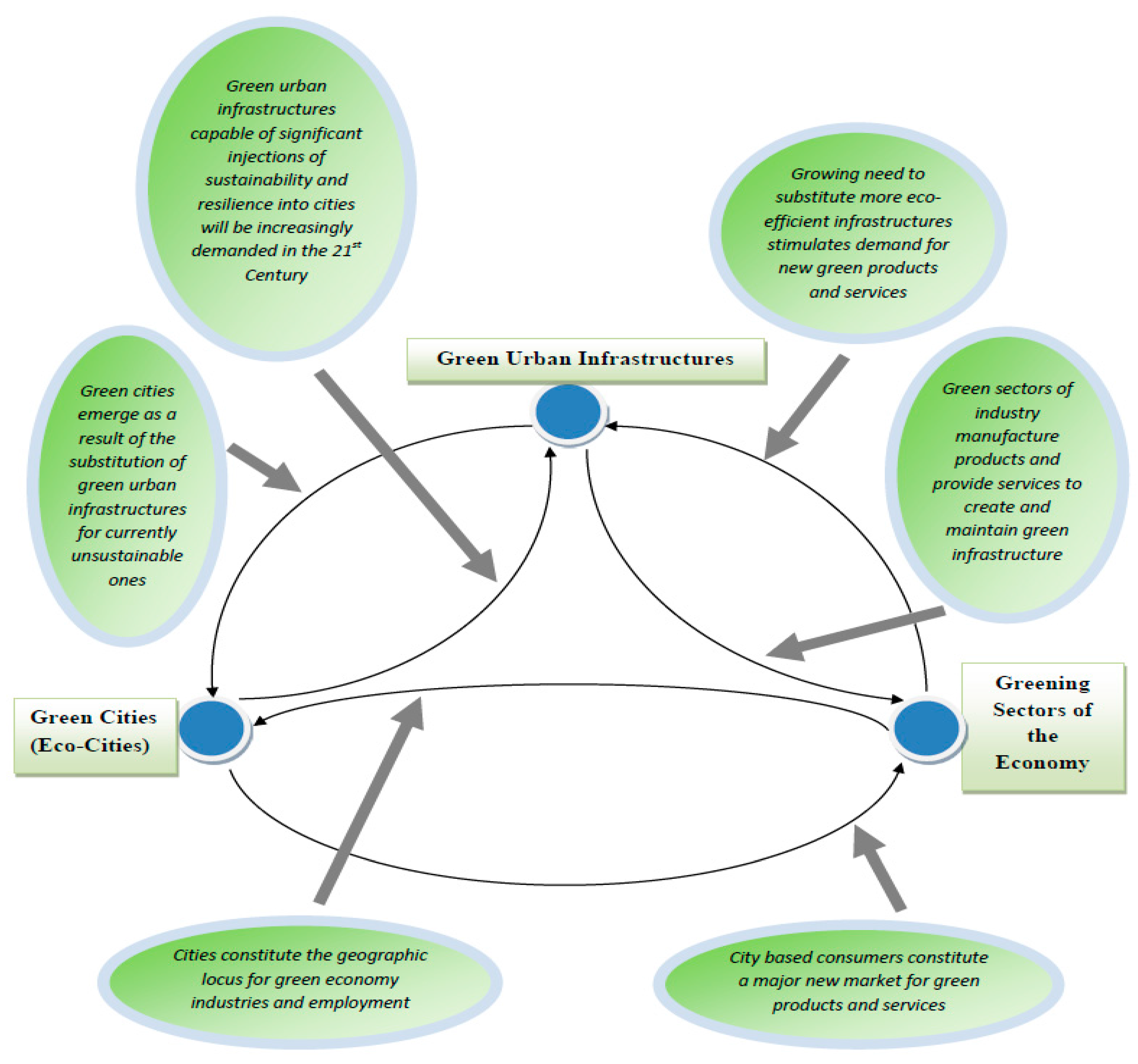

A transition to sustainable urban development will require the emergence of a new form of (green) capitalism based on sustainability principles that embraces social and environmental as well as economic objectives capable of redressing this growing list of problems. The challenge confronting this transition is immense and is the topic of much contemporary debate [

20]. To be successful, the urban sustainability transition will need to be closely integrated with and be a key driver of the emergence of a green economy. They are critically connected (see

Figure 2) and represent the transition arena within which significant urban innovation is required. As current urban sustainability transition theory indicates; however, innovation capable of transformative change currently faces formidable challenges from well-established regimes that represent entrenched industrial, governance and consumer practices [

1,

21,

22].

A range of (green) physical infrastructures are required to support urban living: transport, energy, water, waste, communications and buildings. The consensus is that the sustainability performance of each is currently poor, given that they all emerged in an era where there were few resource constraints and climate constraints. Next generation infrastructures and urban designs will need to demonstrate significantly greater eco-efficiency and resilience in their operation than those that they need to replace [

23]. The demand for new urban infrastructures and green services represents the trigger for a raft of innovative infrastructure technologies to move more widely into the urban marketplace [

22]. In the energy sector, this relates primarily to renewable energy and the speed with which it can penetrate a currently dominant fossil fuel based regime. The resistance being faced in countries with significant fossil fuel endowments or dependencies is shaped by the threat to business and investors of holding the wrong assets. Recent divestment of fossil fuel stocks is a signal that green capitalism will also be based on creative destruction [

24]. However, in this era increasingly centred on new technologies that out-perform existing technologies on sustainability criteria, there will need to be widespread acceptance of rapid change across all industry sectors.

Figure 2.

Critical connections: green economy, green urban infrastructure and green (eco) cities. Source: [

22].

Figure 2.

Critical connections: green economy, green urban infrastructure and green (eco) cities. Source: [

22].

Figure 2 also indicates that cities will constitute a geographic locus for green industry location, given the innovative capacity agglomeration economies deliver to firms generally as well as providing the extensive customer base for new green products and services. It is this spatial convergence of supply and demand forces that will underpin the emergence of a green urbanism and the

eco-city [

25]. A common feature for the sustainability transition, irrespective of sector, will be the critical normative goals addressed: using resources more efficiently and reducing non-renewable resource consumption, reducing emissions and utilising wastes as resources, restoring environmental quality, enhancing human wellbeing, and developing better functioning cities. In all these arenas, governments have a major role to play in setting performance benchmarks and targets for industry and community to achieve, given the challenges that are to be overcome that are beyond any previous era. Consumers are also central to this transition in terms of the signals they send to both industry and government that they are demanding more sustainable living environments (housing, transport/mobility, energy) and domestic products. At present, these demand signals are not strong [

15,

26] and as such represent a challenge (risk) for organisational strategies attempting to introduce more sustainable products and services to the market.

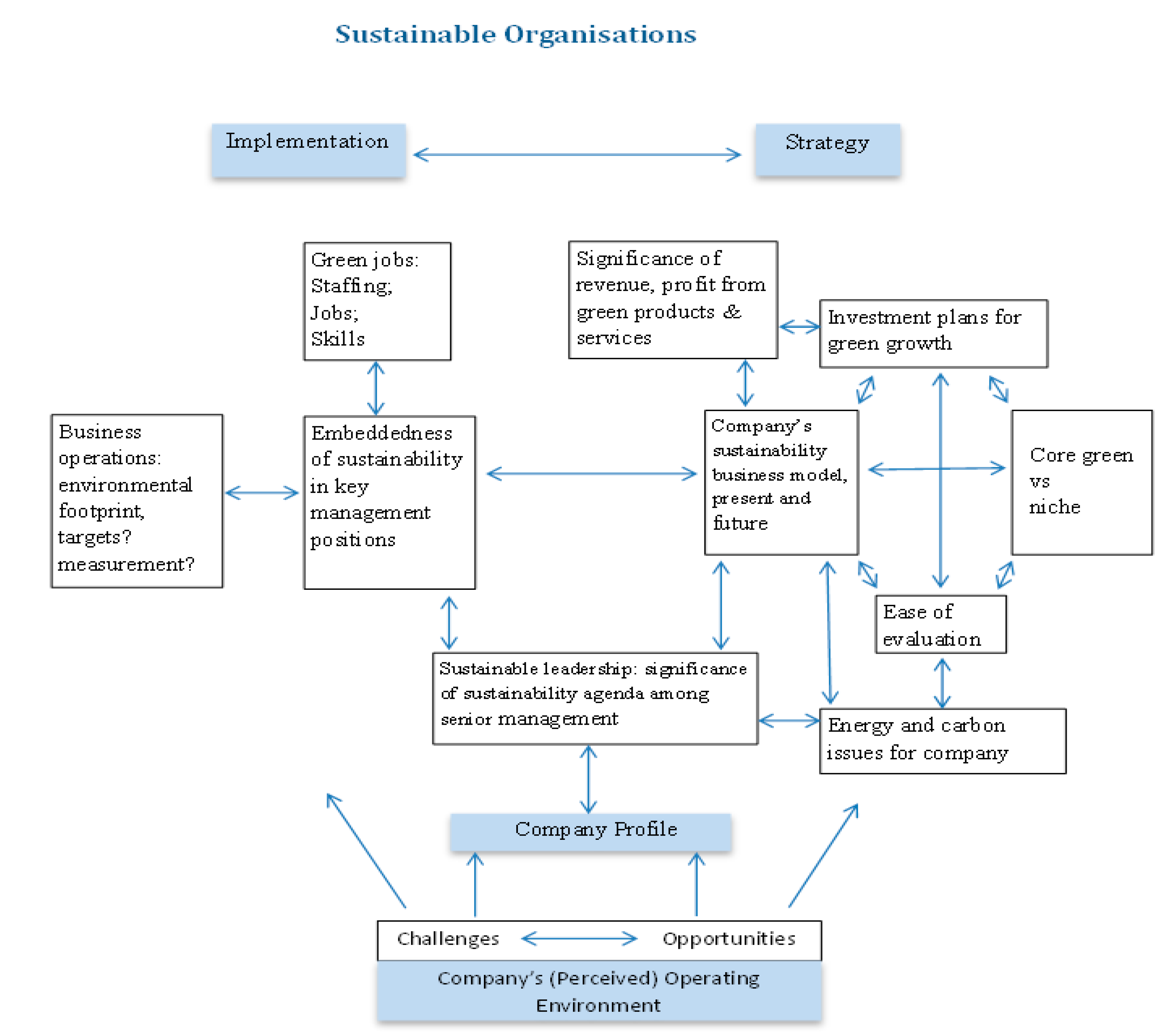

In the next section, we attempt a sketch of some of the dimensions of a green economy as it begins to emerge. We then proceed to explore the directions that Australia’s built environment industries are taking as reflected in senior management’s thinking about their company’s sustainability practices and green growth strategies. They are critical to a green economy transition. The manner in which they assess the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in their operating environment (see

Figure 3)—with particular reference to the current and likely future practices of governments and consumers—will influence the rate at which they are likely to innovate and explore new areas for products and services. The results from a survey of built environment firms undertaken by the authors constitute a marker in assessing the progress towards a green economy and green cities in Australia and internationally.

3. The Carbon Challenge

As discussed earlier, in its narrowest sense, the green economy has been seen to revolve primarily around energy and the transition from fossil fuels to renewables. The Australian Labor government (2007–2013) introduced its Clean Energy Strategy in July 2011 containing a number of measures to reduce the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions, including a carbon tax. In September 2013, there was a change of (federal) government to a conservative Liberal/National coalition that has subsequently repealed the carbon tax, abolished many of the climate-related agencies and programs, reduced the national renewable energy target and has introduced a “direct action” program in an attempt to mitigate growth in CO

2 emissions (many commentators see this as being less effective compared to a price on carbon, with an inadequate budget and untested processes for project assessment and delivery). This watering down of a national commitment to carbon reduction continues to cause local uncertainty (a major concern in the business sector revealed in this and other studies [

72]) as well as international friction in the lead up to the UN Climate Change meeting in Paris in December 2015.

The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) undertook a survey [

73] of 130 Australia-based senior executives prior to the introduction of the carbon tax in Australia. The present survey was undertaken several months after its introduction, which should have provided organisations with an opportunity to begin to gauge its impact on their operations. The two surveys reveal similar percentages in relation to whether organisations overall have a strategy in place for reducing their carbon footprint (see

Table 13). Overall, more than 30% are still lacking such a strategy, with a higher proportion in the private sector.

Table 13.

Organization has a strategy in place for reducing its carbon. (Source: derived from author survey and Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) (2011) [

73].)

Table 13.

Organization has a strategy in place for reducing its carbon. (Source: derived from author survey and Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) (2011) [73].)

| Private n = 90 | Public n = 17 | Total n = 107 | EIU n = 131 | Design | Mfg&Con | Services |

|---|

| No | 35.8 | 14.3 | 32.6 | 30.0 | 34.1 | 28.3 | 50.0 |

| Yes | 64.2 | 85.7 | 67.4 | 70.0 | 65.9 | 71.7 | 50.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Governments currently have a lead role in establishing policies, regulations, pricing and incentives for the green economy. Recent announcements by international scientific groups (IPCC, 2014 [

11] as well as financial institutions World Bank, 2012 [

74]) all point to a likely “4° world” by the end of this century unless significant greenhouse gas mitigation occurs (e.g., ~80% reductions on 1990 CO

2 levels by 2050). There are multiple pathways that have been advanced to decarbonise the built environment [

10,

72,

75] as well as the economy and society more generally. A list of these, based on EIU, 2011 [

73], was incorporated in this survey. The results from private sector respondents are listed in

Table 14.

Table 14.

Preferred government action on carbon reduction (%).

Table 14.

Preferred government action on carbon reduction (%).

| Yes | No |

|---|

| Provide subsidies for clean technology investments by companies | 87.4 | 12.6 |

| Establish incentives for corporate behaviour that leads to low carbon business operations | 87.4 | 12.6 |

| Provision of information on sustainable practices for companies | 87.4 | 12.6 |

| Introduce a performance standard/label for all energy generation technologies | 85.7 | 14.3 |

| Provision of education on green practices for consumers | 85.7 | 14.3 |

| Establishment of national carbon emission reduction goals | 84.0 | 16.0 |

| Subsidies for clean technology usage by consumers | 82.4 | 17.6 |

| Establishment of environmental reporting standards for business | 72.3 | 27.7 |

| Link to an international carbon pricing scheme | 67.2 | 32.8 |

| Introduce carbon labelling for all manufactured products | 62.2 | 37.8 |

| Carbon cap and trade scheme | 55.5 | 44.5 |

| Current federal government carbon pricing scheme | 52.1 | 47.9 |

| Establishment of penalties for lack of carbon efficiency compliance by companies | 50.4 | 49.6 |

| Corporate tax on carbon footprint of business operations | 43.7 | 56.3 |

| Consumer/sales tax on carbon footprint of goods/services consumed | 39.5 | 60.5 |

| Establishment of penalties for lack of carbon efficiency compliance by consumers | 34.5 | 65.5 |

| None of the above—government can help most by doing nothing and letting the market come up with solutions | 9.2 | 90.8 |

Government was clearly endorsed as having a role to play (over 90% of industry respondents in favour), but, from this point, on the directions for intervention varied. The highest proportions of “no” votes by companies were reserved for any imposition of carbon taxes on goods and services consumed as well as consumer-centred compliance, suggesting that more decisive action was required higher up the supply chain. Here, corporate taxes or company carbon compliance charges were among the least favoured actions for governments to take. Incentives and subsidies were clearly favoured over taxes for both consumers and producers. There was strong support for introduction of a performance label for all energy generation technologies as well as incentives for the introduction of clean technologies, both targeting the front end of the energy supply chain—and indicative of “direct action”. National carbon emission reduction goals were endorsed by 84% of business, part of the search for certainty on the part of business and a clear signal to government that more consistency is required.

4. Conclusions

The emergent new low carbon green economy is shaping as the next competitive advantage for industry. This study and the survey on which it is based has demonstrated that in the built environment area, Australian business and government are gearing up for this challenge. There are signs that Australian business is highly aware of the issues and has structured itself to prepare, perhaps even more so than their international counterparts, based on the results of global surveys [

51,

69]. However, the transition is not yet as market-oriented as it could be as many businesses are still waiting to see if consumers will pay a premium for going green; meanwhile, they are doing normal business.

The research revealed that private sector firms are at varying stages of developing green lines of business. The study found that only 13% of companies derive all their revenue from green products or services, with a further 13% receiving at least half from this area of business. Green services have a larger share, but not by a large margin. The challenge is for the 46% of built environment businesses that currently have less than 10% of their sales in green products and services to be actively looking for such opportunities. The significant scope for increasing green revenue is tempered by the high level of uncertainty surrounding a firm’s understanding of what customers are willing to pay for green products and services (55% of respondents—“uncertain”). The challenges of competition, growing revenue and being innovative—among several other traditional business metrics—clearly outranked sustainability issues around the management table when put in the full context of contemporary business operations.

These challenges notwithstanding, sustainability is a permanent agenda item with senior management in 85% of both private sector and public sector organisations responding to the survey (43% of private sector firms have sustainability as a permanent and core agenda item compared to 38% in public sector). The private sector appears more alert to sustainability/low carbon agenda issues than the public sector, possibly because they are more exposed externally to the “front line” of the economy. They are embedding sustainability within all aspects of their organisation’s operations to a greater extent than the public sector (51.6% to 38.1%).

For in-house sustainability and measurement practices, public sector organisations are currently in the lead in terms of having a formal sustainability policy, sustainability manager, sustainability board/committee, reportable sustainability indicators and a sustainability-oriented procurement strategy. Public sector organisations also had higher levels of routine measurement of energy, water and CO2 emissions; the exceptions were with noxious emissions, where there has been mandated reporting for such waste discharges for some time by state environmental protection authorities.

Approximately half of the organisations are yet to change their business model in response to sustainability/low carbon development issues. A primary reason for this is the level of difficulty reported to be associated with evaluating “green” business cases. A comparable percentage indicates that sustainability is yet to be embodied within all facets of operations.

The opportunities identified for green business development within the built environment sector were weak and not representative of the range that currently exist in the marketplace, let alone those that are emerging opportunities. Most of the opportunities identified could be classed as “mature”, reflecting the lack of leading edge “green” innovation currently represented in most urban development projects in Australia.

Two-thirds of organisations surveyed had a strategy in place for reducing their carbon footprint (similar to results from the EIU survey a year earlier). Ninety percent of respondents indicated that government has a lead role to play in encouraging carbon reduction; although there was significant variability in response as to where government intervention should occur. Most favoured areas were subsidies, incentives, information and education. Least favoured were taxes, either on business or consumers.

This survey has demonstrated that, in the built environment area, Australian business and government are gearing up for the green economy challenge. There are signs that Australian business is highly aware of the issues and has structured itself to prepare, perhaps even more so than businesses in other countries, based on the results of global surveys. But the transition is not yet as market-oriented as it could be since many businesses are still waiting to see if consumers will go green and whether governments can offer more consistent policy direction in this area. Meanwhile, they are conducting business as usual. Publicly funded organisations appear to be less market-aware than business but are demonstrating green economy approaches and outcomes at a high level of commitment. Tipping points in all the critical transition arenas are yet to be reached to enable a more rapid shift to a green economy. If Australia is to be a strong global competitor in the green economy and cities are to be core to this transition, then awareness and commitment will need to increase across the board in private and public sector built environment industries—and among consumers. National governments, in particular, need to take a leadership position and then stay the course.