Assessing Child Development: A Critical Review and the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Theme | Human Development Index (HDI) | Children Development Index (CDI) |

|---|---|---|

| Health | Life expectancy at birth | Under five mortality rate |

| Education | Mean years of schooling for adults aged 25 years; expected years of schooling for children of school entering age | Percentage of primary age children not in school |

| Basic needs | Gross national income per capita | Under-weight prevalence among children under five |

2. Review of Themes Related to Sustainable Development of Children

2.1. Basic Rights of Children and Millennium Development Goals

| Right | Theme |

|---|---|

| Right to survival | Physical and mental health |

| Nutrition | |

| Clean drinking water and sanitation | |

| Unpolluted environment | |

| Right to development | Education |

| Leisure | |

| Family relations | |

| Eliminate child labor | |

| Alternative care | |

| Free to choose religion | |

| Right to protection | Free from violence and crime |

| Free from exploitation | |

| Free from abuse | |

| Free from armed conflict | |

| Registration with nationality | |

| Right to participation | Express concern |

| Active participation in media |

- -

- Eradicating extreme poverty and hunger;

- -

- Achieving universal primary education;

- -

- Promoting gender equality and empowering women;

- -

- Reducing child mortality;

- -

- Improving maternal health;

- -

- Combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases;

- -

- Ensuring environmental sustainability;

- -

- Developing a global partnership for development.

- -

- SD starts with safe, healthy and well-educated children;

- -

- Safe and sustainable societies are, in turn, essential for children; and

- -

- Children’s voice, choice and participation are critical for the future that we want them to have.

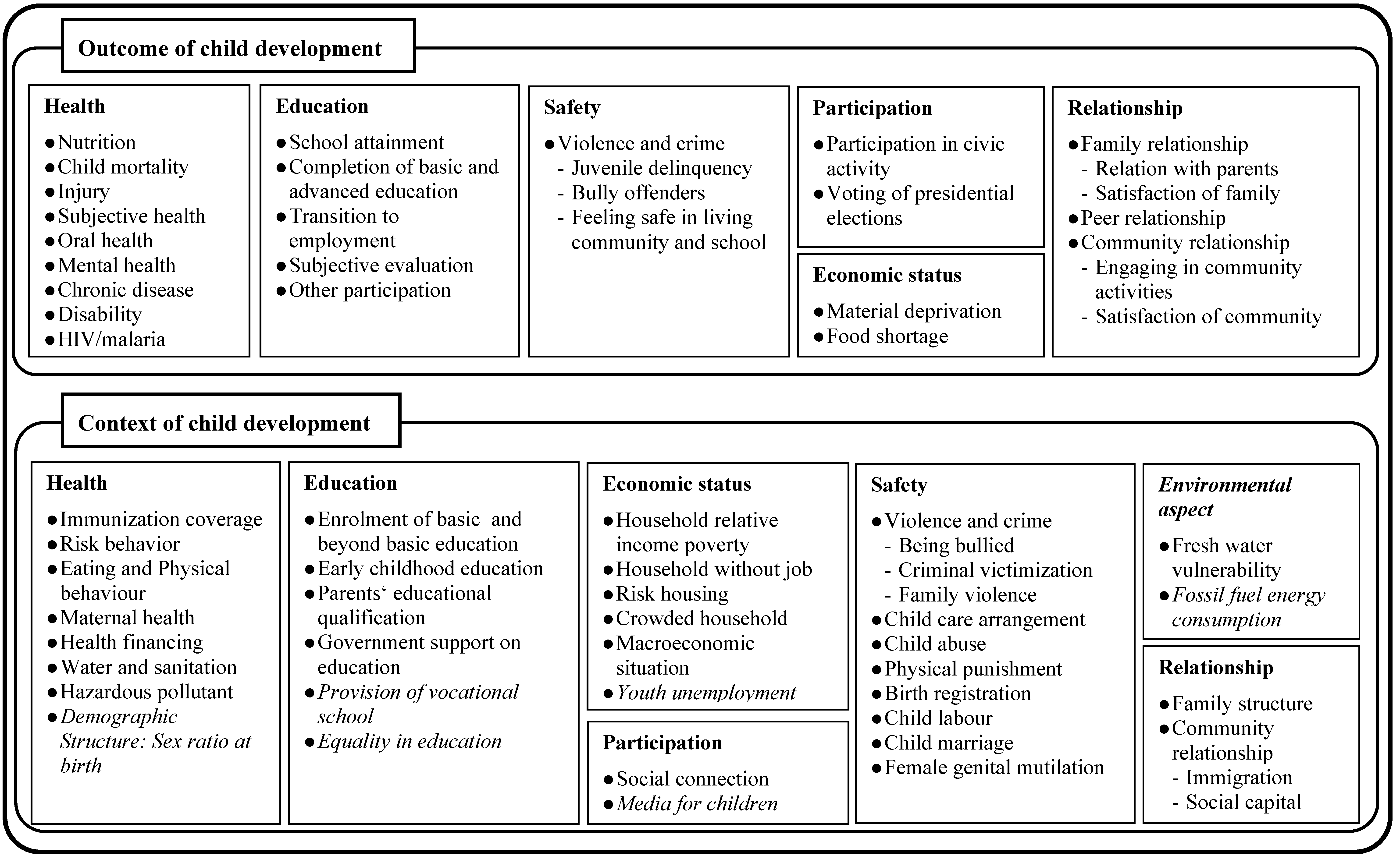

2.2. Identification of Themes, Subthemes and Criteria Relevant for Child Well-Being and Development

2.2.1. Health

- -

- Behavior of children that puts their health at risk needs to be evaluated. Tobacco and alcohol use are two criteria that are identified as relevant for determining the exposure to health hazards, especially for children of school age. In addition, adolescent fertility is also recognized as relevant, as it could damage the immature reproductive system and also increase the risk of venereal disease.

- -

- Sufficient nutrition is a basic need for children and their physical development. Low birth weight, being overweight and obesity, breastfeeding and being underweight are identified as relevant criteria for the subtheme nutrition.

- -

- Reducing child mortality was already suggested in the MDGs and is frequently mentioned in the literature. To determine child mortality, infant mortality and under-five mortality are two commonly suggested criteria.

- -

- Sufficient vaccination programs are representative of the quality of health services (to avoid particular harmful communicable diseases in children). Full immunization, vaccinations for diphtheria tetanus toxoid and pertussis (DTP3) and vaccinations for measles (measles containing vaccine, MCV) are three criteria identified as relevant for evaluating the state of immunization of children.

- -

- Both physical activity and healthy diets help children to strengthen their physiological function. For example, healthy eating behaviors, like having breakfast and eating fruits, are two commonly recommended criteria in the literature.

- -

- Apart from judging health from an objective perspective, the subjective perspective is also relevant. Criteria such as satisfaction and perceived quality of life relate to the subjective health of children.

- -

- Other subthemes, such as oral health, injury, mental health, maternal health, health financing, water and sanitation, child disability, chronic disease and hazardous pollutants, are mentioned, but not frequently addressed in the reviewed literature. HIV and malaria are rarely considered in the reviewed literature, even though they can also affect health and are directly linked to the MDGs.

2.2.2. Education

- -

- The subtheme school attainment can be evaluated by means of the criteria mathematical and reading literacy. Higher literacies indicate that children may have better performance and knowledge obtainment.

- -

- Several criteria are available for evaluating the level of basic education. This links to the MDG ‘achieving universal primary education’. During the literature review, enrollment in primary school is identified as the criteria most often used to assess whether children obtain basic and fundamental knowledge. However, gender equality is assessed only by one study in the literature. Unequal rights in basic education can seriously damage further skill development and also lead to the vicious circle of the situation of females.

- -

- Early childhood education and advanced education are two other subthemes essential to children. Early childhood education is important to attain day-to-day knowledge and to acquire social capability in the initial phases of life. The criteria ‘enrollment in kindergarten’ is identified as the most relevant to reflect the level of early childhood education. Advanced education refers to the attainment of higher levels of knowledge for further development of skills, which plays a key role to strengthen the position of children in the employment market.

- -

- Other subthemes mentioned as relevant for assessing the theme education are transition to employment, parents’ education qualification, other participation (like extra-curricular subjects) and public expenditure on education.

2.2.3. Safety

- -

- Violence in school and juvenile delinquency are identified as the two main criteria for evaluating safety in the literature review. Criteria presumed as relevant, like child trafficking, child prostitution and child pornography, are not evaluated in the currently reviewed literature. These situations occur especially in countries with insufficient laws [10,12].

- -

- Child abuse can cause physical and mental damage and, consequently, has a negative effect on CD.

- -

- Child care arrangement is relevant for ensuring the safety of children. The identified criteria are formal care and adult supervision after school.

- -

- Governmental efforts to ensure child safety, like birth registration, child labor, child marriage, and female genital mutilation (FGM).

2.2.4. Relationships

2.2.5. Economic Status

2.2.6. Participation

| Health (23) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Risk behavior (21) | Nutrition (19) | Child mortality (18) |

|

|

|

| Immunization coverage (15) | Eating and physical activity (12) | Oral health (9) |

|

|

|

| Subjective health (12) | Injury (8) | |

|

| |

| Mental health (8) | Maternal health (7) | Health financing (6) |

|

|

|

| Child disability (5) | ||

| Chronic disease (5) | ||

| Accessibility of health service (3) | ||

| Hazardous pollutant (4) | Water and sanitation (3) | HIV (3) |

|

|

|

| Malaria (2) | School absence due to health issues (2) | Activity limitation (2) |

| Child cancer (2) | Diabetes (1) |

| Diarrhea (2) | Hearing (1) | |

| Asthma (2) | Chlamydia infection (1) | |

| Pneumonia (2) | ||

| Education (23) | ||

|---|---|---|

| School attainment (18) | Early childhood education (12) | Attendance of advanced education (11) |

|

|

|

| Attendance of basic education (10) | Subjective evaluation (9) | Parent’s educational qualification (5) |

|

|

|

| Transition to employment (7) | Other participation (4) | |

|

| |

| Public expenditure on education (2) | ||

| Safety (19) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Violence and crime (14) | Child care arrangement (8) | Child abuse (6) |

|

| Birth registration (2) |

| Child labor (2) | ||

| Child marriage (2) | ||

| Physical punishment (4) | Female genital mutilation (2) | |

| ||

| Economic status (19) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Relative household income poverty (16) | Household without job (9) | Macroeconomic situation (3) |

| Material deprivation (8) | Risk housing (8) |

|

| Food shortage (5) | |

| Crowded household (4) | ||

| Debt and financial difficulties (2) | ||

| Worry about family financial situation (2) | ||

| Relationship (17) | ||

| Family relationship (17) | Peer relationship (8) | Community relationship (8) |

|

|

|

| Participation (6) | ||

| Participation in civic activity (4) | Social connection (3) | Voting in presidential elections (3) |

| ||

2.3. Gaps and Challenges of Assessing CD

2.3.1. Inconsistent Definitions of the Age of Children

2.3.2. Heterogeneous Classification of Relevant Aspects

2.3.3. Interdependencies

2.3.4. Regional and Societal Bias

- -

- Only two studies cover the situation in developing countries [46,47]. So far, not enough attention is put on issues of particular relevance for developing countries, such as hunger, access to water, sanitation, malaria, diarrhea, etc. As a consequence, the criterion “overweight and obesity” is associated with higher attention in the current literature than the criterion “underweight”. Furthermore, access to water is generally assured, and sanitation systems are available in industrialized countries, leading to the negligence of those criteria in many studies. In addition, malaria and diarrheal disease, which are very critical to young children, receive little attention in the reviewed literature [47], as they mainly occur in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

- -

- -

- Societal preferences lead to criteria like the proportion of children living in single-parent families and stepfamilies, which is often used to negatively judge family relationship. However, children in single-parent and stepfamilies can still grow up well [28]. Similarly, regarding child labor, usually negative impacts, like increasing health risks and deteriorating school performance, are mentioned and observed; however, some positive effects, like the development of discipline, responsibility and self-confidence, may also occur [60]. It is very complicated to establish straightforward cause and effect relations with regard to CD due to the multi-faceted character of social issues.

2.3.5. Limited Subthemes and Criteria

2.3.6. Lack of Including Environmental Aspects

3. The Sustainable Child Development Index

- -

- Vocational education (may include technical schools, workshop schools, development agencies, etc. [55]) is designed to prepare individuals for a vocation or a specialized occupation and is directly linked with a nation’s productivity, competitiveness and equality in education. It can increase further career development opportunities and professional status [62]. Quality of life of children and personal development, attitudes and motivation can also be affected by vocational education.

- -

- Equality in education is essential for all children. Gender equality in education plays a core role in protecting children’s basic right to education. If gender equality is low, this leads to a vicious circle in the further personal development of girls, human capital and gender conflicts in society.

- -

- The global youth unemployment rate in 2013 was 12.6%, close to a crisis critical peak [63]. Although children are defined as aged 0–18 earlier, youth (aged 15–24) unemployment can reflect the prosperity of job opportunities and can influence children’ plans for further education, career and development of skills. The economic and social costs of unemployment and widespread low quality jobs for young people continue to rise and undermine the potential of economies to grow [63].

- -

- Media (newspapers, periodicals, books, broadcasts, websites, television shows and news, etc.) designed for children is important for children to attain knowledge and to participate in public affairs by expressing their opinions. Furthermore, well-designed media can provide information without harmful content, such as violence and pornography.

- -

- Fossil fuel is a non-renewable energy source. High fossil fuel energy consumption speeds up the depletion of fossil fuel resources and damages the rights of future generation to access these resources. Each country should reduce the consumption of fossil fuel and should implement measurements to promote renewable energy.

- -

- Demographic structure (especially the sex ratio at birth, estimated as the number of boys born per 100 girls) can reflect the attitude towards gender equality in society. High sex ratios at birth may be attributed to sex-selective abortion, infanticide and underreporting of female births due to a strong preference for sons [64,65]. Exposure to pesticides and other environmental contaminants may be a significant contributing factor, as well.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm (accessed on 11 January 2014).

- Van de Kerk, G.; Manuel, A. Sustainable Society Index 2012; Sustainable Society Foundation: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K. The sustainable development area: Satisfying basic needs and safeguarding ecological sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waas, T.; Hugé, J.; Verbruggen, A.; Wright, T. Sustainable development: A bird’s eye view. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1637–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Glossary of Environment Statistics; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations; European Commission; International Monetary Fund; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; World Bank. Handbook of National Accounting: Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting 2003; World Bank: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, N.; Maas, R.; Goralcyk, M.; Wolf, M.-A. Towards a Life-Cycle Based European Sustainability Footprint Framework; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, J.; United Nations Development Programme. Sustainability and Human Development: A Proposal for a Sustainability Adjusted HDI (SHDI); Munich Personal RePEc Archive: Münich, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature Resource; United Nations Environment Programme; World Wildlife Fund. World Conservation Strategy—Living Resource Conservation for Sustainable Development; International Union for Conservation of Nature Resource: Gland, Switherland, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Rights of the Child; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the rights of the child. Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (accessed on 11 July 2014).

- United Nations Children’s Fund. A Post-2015 World Fit for Children—Sustainable Development Starts and Ends with Safe, Healthy and Well-Educated Children; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halleröd, B.; Rothstein, B.; Daoud, A.; Nandy, S. Bad governance and poor children: A comparative analysis of government efficiency and severe child deprivation in 68 low- and middle-income countries. World Dev. 2013, 48, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, M.; Schau, E.M.; Lehmann, A.; Traverso, M. Towards life cycle sustainability assessment. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3309–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Towards a Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment-Making Informed Choices on Products; United Nations Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. The Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products; United Nations Environment Programme: Druk in de weer, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Human Development Report 2013: Human Progress in a Diverse World; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao-Ubillos, J. The limit of human develoment idex: The complementary role of economic and social cohesion, development strategies and sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togtokh, C.; Gaffney, O. 2010 Human Sustainable Development Index. Available online: http://ourworld.unu.edu/en/the-2010-human-sustainable-development-index (accessed on 17 March 2014).

- Morse, S. Bottom rail on top: The shifting sands of sustainable development indicators as tools to assess progress. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2421–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the Children Fund. The Child Development Index 2012—Progress, Challenges and Inequality; Save the Children Fund: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children Fund. The child Development Index—Holding Governments to Account Children’s Wellbeing; Save the Children Fund: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, A. The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, A. From child welfare to children well-being: The child indicators perspective. In From Child Welfare to Child Well-Being—An International Perspective on Knowledge in the Service of Policy Making; Kamerman, S.B., Phipps, S., Ben-Arieh, A., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Arieh, A. The child indicators movement: Past, present, and future. Child Indic. Res. 2008, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Children’s Society. The Good Childhood Report 2013; Children’s Society: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation for Child Development. Child and Youth Well-Being Index (CWI); Foundation for Child Development: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. An Overview of Child Well-Being in Rich Countries; United Nations Children’s Fund: Florence, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Child Rights and You. Child rights. Available online: http://www.cry.org/CRYCampaign/ChildRights.htm (accessed on 9 October 2013).

- Child Rights International Network. Child right themes. Available online: http://www.crin.org/en/home/rights/themes (accessed on 11 January 2014).

- United Nations. United nations millennium declaration. Available online: http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm (accessed on 2 April 2014).

- Minkkinen, J. The structural model of child well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2013, 6, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, P.R.; Ulkuer, N. Child development in developing countries: Child rights and policy implications. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme. The millennium development goals—Eight goals for 2015. Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/mdgoverview/ (accessed on 2 April 2014).

- Lee, B.J.; Kim, S.S.; Ahn, J.J.; Yoo, J.P. Developing an Index of Child Well-Being in Korea. In Proceedings of the 4th International Society of Child Indicators Conference, Seoul, Korea, 29–31 May 2013.

- Niclasen, B.; Köhler, L. National indicators of child health and well-being in Greenland. Scan. J. Public Health 2009, 37, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, L. A Child Health Index for the North-Eastern Parts of Göteborg; Nordic School of Public Health: Göteborg, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.Y.-N. A clustering approach to comparing children’s wellbeing accross countries. Child Indic. Res. 2014, 7, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbstein, N.; Hartzog, C.; Geraghty, E.M. Putting youth on the map: A pilot instrument for assessing youth well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2013, 6, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.; Hoelscher, P.; Richardson, D. An index of child well-being in the european union. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 80, 133–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.J. Mapping domains and indicators of children’s well-being. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2797–2805. [Google Scholar]

- Land, K.C.; Lamb, V.L.; Meadows, S. Conceptual and methodological foundations of the child and youth well-being index. In The Well-Being of America’s Children—Developing and Improving the Child and Youth Well-Being Index; Land, K.C., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafin, S.; Brooks, A.-M.; Carroll, E.; Fitzgerald, E.; GaBhainn, S.N.; Sixsmith, J. Achieving consensus in developing a national set of child well-being indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 80, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, K.C.; Lamb, V.L.; Meadows, S.; Zheng, H.; Fu, Q. The CWI and its components: Empirical studies and findings. In The Well-Being of America’s Children—Developing and Improving the Child and Youth Well-being Index; Land, K.C., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 29–75. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A.; Mbwana, K.; Theokas, C.; Lippman, L.; Bloch, M.; Vandivere, S.; O’Hare, W. Child Well-Being: An Index Based on Data of Individual Children; Child Trends: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. The State of the World’s Children 2014 in Numbers: Every Child Counts; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Childinfo: Monitoring the situation of children and women. Available online: http://www.childinfo.org/ (accessed on 11 March 2014).

- Mather, M.; Dupuis, G. The New Kids Count Index; The Annie E. Casey Foundation: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Social Development. Children and Young People: Indicators of Wellbeing in New Zealand 2008; Ministry of Social Development: Wellington, New Zealand, 2008.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Headline Indicators for Children’s Health, Development and Wellbeing 2011; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- European Union Community Health Monitoring Programme. Child Health Indicators of Life and Development; European Union Community Health Monitoring Programme: Luxemburg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being 2013; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Social Determinants of Health and Well-Being among Young People; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A.; Murphey, D.; Bandy, T.; Lawner, E. Indices of child well-being and developmental contexts. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2807–2822. [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Menoyo, M.Á. Educating for local development and global sustainability: An overview in spain. Sustainability 2009, 1, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, L. Municipal indicators for children’s health in Sweden. In Proceedings of the 1st International Society of Child Indicators Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–28 June 2007.

- Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion. Measuring the Health of Infants, Children and Youth for Public Health in Ontario: Indicators, Gaps and Recommendations for Moving Forward; Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare, W.P.; Gutierrez, F. The use of domains in constructing a comprehensive composite index of child well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2012, 5, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arieh, A.; Casas, F.; Frønes, I.; Korbin, J.E. Multifaceted concept of child well-being. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, A.; Lai, L.C.H.; Hauschild, M.Z. Assessing the validity of impact pathways for child labour and well-being in social life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, V.L.; Land, K.C. Methodologies used in the construction of composite child well-being indices. In The Handbook of Child Well-Being—Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 2739–2755. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. The Benefits of Vocational Education and Training; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2013; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund. Report of the International Workshop on Skewed Sex Ratios at Birth; United Nations Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeswar, J. Population perspectives and sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2000, 8, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Y.-J.; Schneider, L.; Finkbeiner, M. Assessing Child Development: A Critical Review and the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI). Sustainability 2015, 7, 4973-4996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7054973

Chang Y-J, Schneider L, Finkbeiner M. Assessing Child Development: A Critical Review and the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI). Sustainability. 2015; 7(5):4973-4996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7054973

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Ya-Ju, Laura Schneider, and Matthias Finkbeiner. 2015. "Assessing Child Development: A Critical Review and the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI)" Sustainability 7, no. 5: 4973-4996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7054973

APA StyleChang, Y.-J., Schneider, L., & Finkbeiner, M. (2015). Assessing Child Development: A Critical Review and the Sustainable Child Development Index (SCDI). Sustainability, 7(5), 4973-4996. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7054973