1. Introduction

Decentralization and its embodiment in environmental governance—community-based natural resource management (CBNRM)—is often considered a remedy or even a panacea to environmental, governance and social challenges [

1,

2].

Mainly seen as a key to better governance at sub-national levels [

3,

4,

5], CBNRM has become a prominent policy reform approach in a number of countries, particularly in those states and, often rural, areas where the public administrative system is considered to underperform. Hence, in many countries supported by the donor community, which has endorsed CBNRM as a key reform concept [6,7], CBNRM programs and CBNRM-related formal laws and regulations are being implemented. This has specific implications: unlike exemplary cases of endogenously-created sustainable self-governance of natural resources [8,9], from which common-pool resource theory and the CBNRM paradigm have evolved, CBNRM today is externally designed and introduced.

The external introduction of CBNRM, for example by donor organizations directly or by governmental or government-mandated implementing agencies, is problematic, and the results are mixed. Besides success [

10,

11,

12,

13], research has documented many cases of failure, either in terms of conservation impact [

14,

15] or social equity outcomes [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

CBNRM depends on resource user involvement: “CBNRM […] requires some degree of devolution of decision-making power and authority over natural resources to communities and community-based organizations… [CBNRM] seeks to encourage better resource management outcomes with the full participation of communities and pasture users in decision-making activities, and the incorporation of local institutions, customary practices, and knowledge systems in management, regulatory, and enforcement processes.” (Armitage 2005, quoted in [

21] (p. 53)). However, several studies have found that effective resource user involvement, considered by many an important prerequisite for sustainable and equitable self-governance [21–26], is difficult to achieve [

27]. The characteristics of CBNRM implementation strategies and the resulting interaction among policy implementers and resource users play a decisive role for CBNRM implementation outcomes [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. This interaction is particularly difficult in societies with a long history of top-down government [

34] where CBNRM is being introduced.

The general objective of this article it to explore how a CBNRM implementation strategy and the resulting interaction among lowest-level policy implementers and resource users influence resource user participation in CBNMR by means of information rule design. The research was motivated by a general aim to contribute to filling a knowledge gap in the distributional impact of municipality-level CBNRM implementation, for which I assume information access a precondition. I assume that access to information is determined by information rules; that is, prescriptions that “authorize channels of information flow among participants, assign the obligation, permission, or prohibition to communicate [specific knowledge] to participants (…), and [define] the language and form in which communication will take place” [

35] (p. 206). I further assume that information rules are being created in the process of policy implementation. In order to contribute to the general objective of this study, I specifically study an example of CBNRM implementation in Kyrgyzstan—the introduction of a community-based pasture management reform—and investigate the following research questions:

Which specific information rules do local-level policy implementers (whom I define as street-level bureaucrats (SLB)) design during the implementation of the Kyrgyz community-based pasture management reform?

How do these information rules influence resource user involvement opportunities in community-based pasture management in Kyrgyzstan?

How do the implementation strategy describing street-level bureaucrats’ information tasks and the governance structure within which street-level bureaucrats’ operate influence their information rule design?

In the following

Section 2, I introduce the analytical framework, which proposes that resource user involvement in CBNRM depends to a large degree on the characteristics of routines (in other words, working rules), which policy implementers create to simplify the information transfer transaction. In

Section 3, I describe the case study in Kyrgyzstan, where community-based pasture management was introduced by the law “On Pastures” (Pasture Law), which was issued in 2009. In

Section 4, I explore how different types of policy implementers informed resource users and how the course of action they chose impacted pasture users’ awareness of CBNRM (and of the implicit participation opportunities). In

Section 4.1, I first summarize the policy implementation tasks allocated to policy implementers and outline the formally-prescribed rules for resource user information.

Section 4.2 reviews the working conditions and governance structures under which the two groups of policy implementers perform these information tasks: municipality administrators and the staff of an implementing organization (ARIS), called the Community Development Support Officers.

Section 4.3 reports on pasture users’ information about participation opportunities under CBNRM management. In

Section 4.4, I explore the information routines created by policy implementers.

Section 4.5 discusses the reasons for the emergence of these routines. In

Section 5, I present the theoretical and practical implications of the study.

2. Analytical Framework

In this section, I develop a modified version of the Institutions of Sustainability framework [

36,

37] (IoS framework), which acknowledges case study-relevant contributions from public administration research in order to more specifically acknowledge the characteristics of actors and governance structures, characteristics particular to implementation situations, which have not been specified in other frameworks.

The analytical framework is a modified version of the IoS framework [

36,

37], which takes the following four determinants of institutional change into account: (1) the properties of transactions; (2) the characteristics of existing institutions; (3) the characteristics of actors; and (4) the governance structures. Due to space limitations, the following outline of the IoS framework is not exhaustive. I only focus on the most crucial elements. For a detailed description of the framework’s approach, see the works of Hagedorn and colleagues [

36,

37].

Transactions have been identified as the “unit of activity” [

38] (p. 651) and are often considered the starting point of institutional analysis [

36]. In this article, I explore a policy implementation transaction during which “a policy is put into action and practice” [

39] (p. 461). Policy implementation transactions consist of a number of sub-transactions. The paper looks at one specific sub-transaction: the process of transferring CBNRM-related information to users of natural resources, in adherence to the principle of resource user involvement in CBNRM. This transaction I call the information transfer transaction.

Institutions are “systems of established and embedded social rules that structure social interaction” [

40]. They can be formal (in other words, written) rules,

i.e., codified laws, or (often unwritten) working rules [

41,

42]. Working rules (sometimes also called rules-in-use) are those rules that are “actually used, monitored, and enforced when individuals make choices about the actions they will take” [

35] (p. 51). Institutions are nested within other rules [

43]. Hence, besides exploring the institutional outcome of the policy implementation transaction—the information working rules—institutional analysis also requires taking into account the institutional setting—the rules that structure the policy implementation transaction itself. These are formal rules found in the law and in written implementation instructions, as well as relevant informal rules of conduct.

In the proposed study framework, the actor component has a prominent role. I take a bottom-up perspective on policy implementation (for an overview, see, e.g., [

44] (pp. 51ff), according to which the actions of service providers who operate at the lowest administrative levels (commonly referred to as street-level bureaucrats (SLBs) [

45,

46,

47,

48]) are considered the most important determinants of a policy’s local effect. Implementation studies have shown the relevance of policy implementer networks [

49] in which different types of SLBs play a role. Note that SLBs do not necessarily live close to their clients; they are those members of policy implementing organizations who have regular and close interaction with those for whom they are to provide services. It is therefore useful to further distinguish between external and local SLBs, both of which operate in different governance structures. Local SLBs are bureaucrats operating at the lowest level of state administration. Their offices are permanently located in the municipality where they serve. External SLBs, in contrast, are representatives of non-local administrations, donor organizations or NGOs.

Governance structures within which transactions occur and actors operate are organizational constructs that establish order, mitigate conflict and ensure mutual gains [

50] (p. 4). They have three forms: (1) market; (2) hierarchy; or (3) a type of hybrid institutional arrangement, where private and public elements intertwine. These governance structures differ by cost and competence and impose different incentives and controls on actors, which lead to different degrees of autonomy and cooperation [

51] (p. 271f). SLBs are, by definition, employed in hierarchical organizations. In hierarchies, actors’ actions are highly controlled and coordinated. Hierarchies therefore generate few incentives and constrain autonomy [

51]. The governance structure of street-level bureaucracy is not a pure version of hierarchy. The specific working conditions of the SLB increase individual autonomy and limit administrative control. By influencing SLBs’ perception of the rewards and costs of their activities, the governance structure impacts the discretionary competence of SLBs:

SLBs’ actions are constrained by their working conditions, which, to a large extent, depend on their subordination to an implementing organization, which can be not only a government office, but also a civil society organization [

45];

SLBs work in relative spatial distance from the employing organization, but in relative spatial proximity to the citizens that they serve;

they are confronted with ambiguous role expectations from their employing organization and from local clients with whom they interact daily;

they have to deal with resource constraints, but are confronted with the service demands of their clients, which exceed available capacity;

SLBs deal with laws and rules external or internal to their employing organization, which often fail to cover the diversity of cases that they have to handle, because SLBs often need to judge case by case and, therefore, have some degree of discretion [

47,

48].

SLBs therefore experience a paradox situation, as they “see themselves as […] oppressed by the bureaucracy within which they work. Yet they often seem to have a great deal of discretionary freedom and autonomy” [

44] (p. 52).

SLBs actively design those working rules for policy implementation that are decisive for implementation outcomes. Hence, all SLBs can be equated with policy implementers. SLBs use their discretionary freedom to create routines and simplifications. “Routines are the regularized or habitual patterns by which tasks are performed. Simplifications are symbolic constructs in terms of which decisions about potentially complex phenomena are made, utilizing a smaller set of clues than those presented by the phenomena. Routines are behavioral patterns of response; simplifications are mental patterns of ordering data with which routines may or may not be associated” [

48] (p. 225).

SLBs develop routines and simplifications by assessing rewards and penalties and the available resources. Moreover, routines and simplifications let SLBs “organize their work to derive a solution within the resource constraints they encounter” [

48] (p. 83). Therefore, the characteristics of the policy implementation working rules that SLBs develop depend on their relationship to their organization.

Frequently, the resulting working rules deviate from formal rules and can even be “entirely informal and contrary to agency policy” [

48] (p. 86), because the SLBs choose either a specific way of executing an existing rule or select one specific rule among a set of rules [

45]. SLBs’ simplification strategies might differ, as the selection of simplifications and routines depends on individual perceptions of adequate professional behavior, one’s own perceptions of tasks,

etc., but also on individual differences in the evaluation of options to overcome resource constraints [

52]. Administrators (also SLBs) “satisfice rather than maximize” [

53] (p. 119). The decisions they make are impacted by a specific perception of the implementation task. This perception is determined by: (1) personal beliefs, including predispositions about how the job is to be done; (2) previous experiences; (3) sensitivity to professional standards; (4) political ideology; and (5) personal characteristics [

52].

It is nevertheless assumed that the routines and simplifications that SLBs employ share some characteristics: (1) they tend to limit access to and demand for SLBs’ services; (2) they maximize the utilization of available resources; and (3) they aim to obtain client compliance over and above the procedures developed by their employing organization [

48].

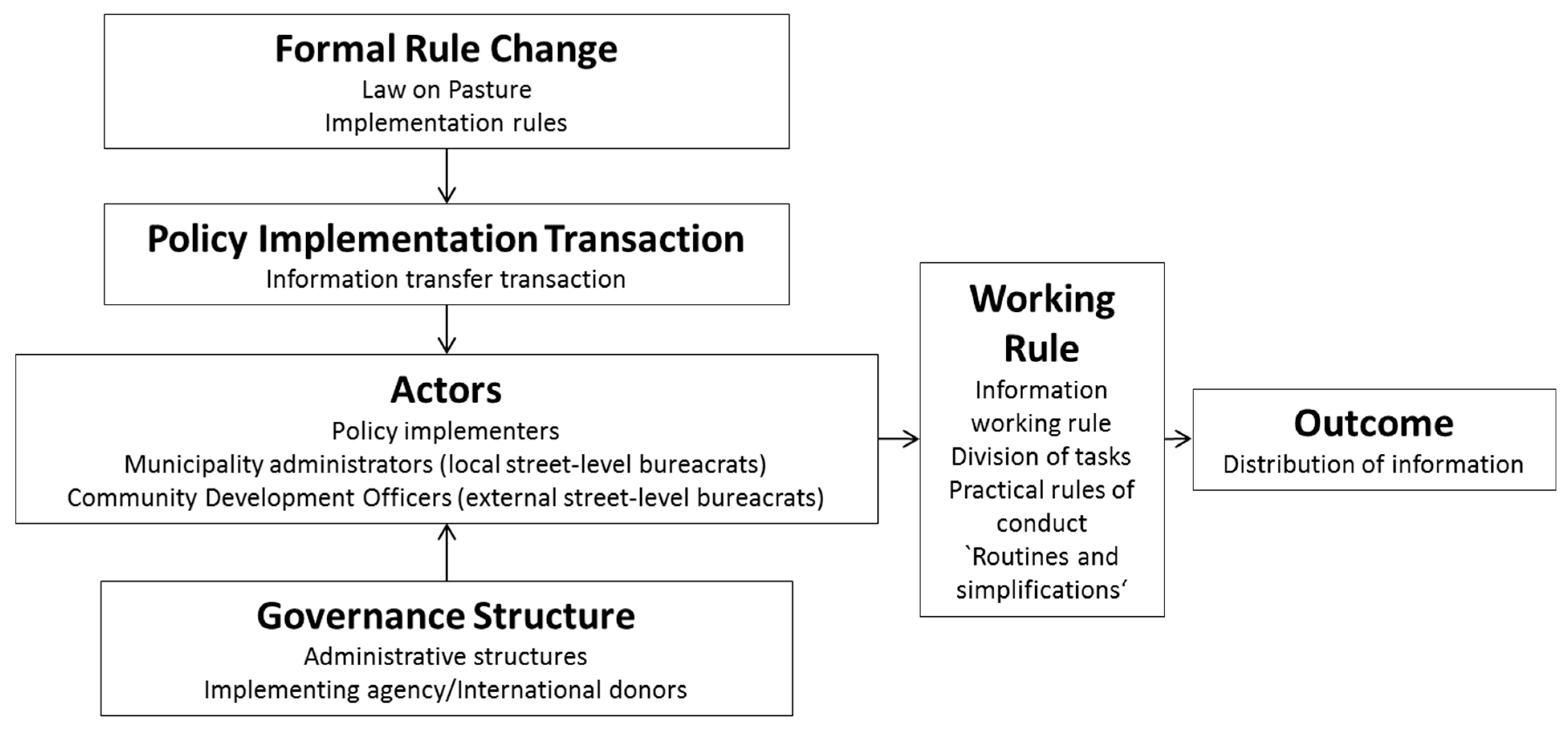

Hence, the case studies’ analytical framework (see

Figure 1), which is based on the actors and governance structure component of the IoS, proposes the following relationships: First, the studied transaction is part of the implementation of a new policy. Second, the actors are SLBs, who carry out the policy implementation transaction,

i.e., they execute a formal information rule. Third, SLBs are assumed to be bound to hierarchical governance structures and the associated rules for task performance. Fourth, during local-level implementation, the SLBs design working rules, which allocate CBNRM resource user opportunities to resource users.

I assume that information working rules are routines that are consciously designed by SLBs, depending on three factors: First, the characteristics of the policy implementation transaction; second, the SLBs’ perception of the implementation task; third, the governance structure, including its relevant institutions or rules of conduct. To select a specific course of action, SLBs coordinate their task perception with the given rules of conduct and the associated rewards and responsibilities imposed by their agency. In addition, they acknowledge that their actions are embedded in accountability relationships, such as the rules enforced by their governance structure.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework.

3. Material and Methods

The Kyrgyz Republic (Kyrgyzstan) is a Central Asian country, which belonged to the Soviet Union until 1991. The country is highly mountainous, and vast areas are dominated by pasture lands and agro-pastoral land use: 97 percent of the area is located 1000 m above sea level, and of the roughly 10.5 million hectares of agricultural land, 9.2 million hectares are classified as naturally-grown permanent meadows and pastures [

54]). The changes in the distribution of property rights that were associated with the break-up of the Soviet Union also impacted pasture management in the country. Currently, the second pasture management reform, which embodies CBNRM principles and replaced a lease-based approach [55,56], is in place.

In 1996, so-called local self-governments were established at the municipality level. Those bodies consist of an administrative apparatus (municipality administration) and a municipality council. Until 2008, both the head of the local self-government and the council members were elected by popular vote. The local self-governments are formally independent of the Kyrgyz central state and its offices at the regional and district levels. In practice, however, local self-governments at the municipality level report to and execute orders from the district-level state administrations [

57,

58,

59].

On 26 January 2009, a new law titled “On Pastures” (Pasture Law) was issued by the Pasture Department of the Kyrgyz Ministry of Agriculture, Water Resources and Processing Industry (MAWRPI). The Pasture Law replaced a pasture leasing system that had been in place since 2002 [

56,

60] and which had come under severe criticism for its inability to cope with growing pasture land degradation [

60]. It devolved pasture management rights form regional and district level braches of the central government to local self-governments and community-based organizations, called Pasture User Unions (PUUs), and their executive bodies, called pasture committees. By law, all municipality residents are to become members of the PUU. Devolution granted collective rangeland management rights to the PUUs and entitled them to distribute seasonal pasture use rights to individual herders, to fix annual grazing fees based on animal numbers and endowed them with a dispute resolution authority and the right to use revenue from fee collection for management and investment in pasture infrastructure.

I used empirical data from a case study [

61] at three sites in rural Kyrgyzstan. The study sites were chosen according to a maximum variation sampling logic [

62] based on initial assumptions about different degrees of resource user involvement in CBNRM implementation.

Data for this study were compiled in different phases (see

Table 1). In the first phase, in July, 2009, expert interviews on the community-based pasture management reform, initiated by the introduction of the Pasture Law, were held. In addition, existing implementation experience was discussed in the Ala Too and Bulak municipalities, which the researcher knew from previous data collection activities in Kyrgyzstan. These interviews revealed that in both municipalities, some activities for pasture committee establishment were already ongoing. It was noted that these processes differed in their approach and that the lack of implementation instructions for the Pasture Law had left great room for discretion at the municipality level. In the second phase, after the research question had been specified further, the Kara Tash municipality was added to the set of case study municipalities. This municipality was selected because, unlike the other two municipalities, NGO staff had reported that pasture committees had been established here in a more participatory process. This NGO had been experimenting with community-based pasture governance before the Pasture Law was issued. In August, September and October, 2009, in-depth village-level data were collected (the background interviews are not listed in

Table 2 because the generated information served only for the identification of the case study sites). At that time, the implementing organization had arrived in the municipalities and started to complement the activities of the municipality administrators (for further details of this two-phase implementation process, see [

55]), and the pasture committee establishment process was still ongoing at all study sites.

Table 1.

Timing of events and study activities.

Table 1.

Timing of events and study activities.

| | Pasture Law Implementation Activities | Data Collection Activities |

|---|

| May−July 2008 | | Data collection in the municipalities of Ala Too and Bulak (different research focus);

background interviews with pasture law designers and pilot project implementers in the municipality of Kara Tash |

| November 2008 | Pasture committee foundation in Kara Tash | |

| January 2009 | Law “On Pastures” signed | |

| July 2009 | District-level bodies of local state administration ordered pasture committee establishment at the municipality level (presumably after the draft of the presidential decree on the implementation specifications for the “On Pastures” law (Draft for Decree N 386; 16 June 2009) became public; to the knowledge of the author, this decree was not signed into force);

Pasture committee foundation in Ala Too;

Pasture committee foundation in Bulak | Data collection at national level;

data collection in municipalities Ala Too and Bulak |

| August 2009 | Community Development Officers of implementing organization received training | Data collection at the national (continued) district and municipality level;

data collection in the municipalities of Ala Too and Bulak (continued);

data collection in the municipality of Kara Tash |

| September 2009 | Community Development Officers of implementing organization start implementation activities |

| October 2009 | (Internal) registration deadline for pasture committees set by implementing organization |

Working rules with different degrees of deviation from the working rules for pasture committee establishment were expected at each site (see

Table 3 for an overview of the observations). However, as will be shown below, in-depth case study work revealed that this diversity of working rules did not actually exist (what was first misunderstood as the ordered dissolution of one of the pasture committees due to its non-participatory establishment process was actually only a dissolution on paper; the committee was later revived in exactly the same composition, with only a few additional new members, who were official office holders.) Contrary to the initial assumption, all three pasture committee formation processes followed basically the same general procedure with only cosmetic variations. In none of the cases was there any drastic variation in the approaches that policy implementers used.

Table 2.

Number of policy implementation expert interviews.

Table 2.

Number of policy implementation expert interviews.

| Policy implementation organization | Number of policy implementation experts interviewed |

|---|

| Ministry of Agriculture, Water Resources and Processing Industry (MAWRPI) Staff | 1 |

| Community Development and Investment Agency (ARIS) staff (Leadership and Community Development Officers) | 4 |

| Municipality administration staff | 5 |

| Pasture committee members | 8 |

Table 3.

Case study selection criteria.

Table 3.

Case study selection criteria.

| Municipality | Researchers’ Perception of Pasture Committee Formation Process |

|---|

| Ala Too | |

| Bulak | Pasture committee was established by municipality administration; Selected, wealthy livestock owners involved only

|

| Kara Tash | |

As this paper is subject to a confidentiality agreement with all respondents, the names of the municipalities have been changed and their locations are not pinpointed. All municipalities lie in key livestock production areas in northern Kyrgyzstan, where agro-pastoralism is the dominant source of income. All resident families, except for the poorest, own livestock and use pastures for grazing, either directly, as herders, or indirectly, as users of herding services. In the studied municipalities, agro-pastoralism is the common practice. Herders spend the period from May to October on pastures outside of the village; some travel to summer pastures at altitudes above 2500 m (a detailed description of the migration pattern is found in Steimann [

63] and Schoch and Steimann [

64]).

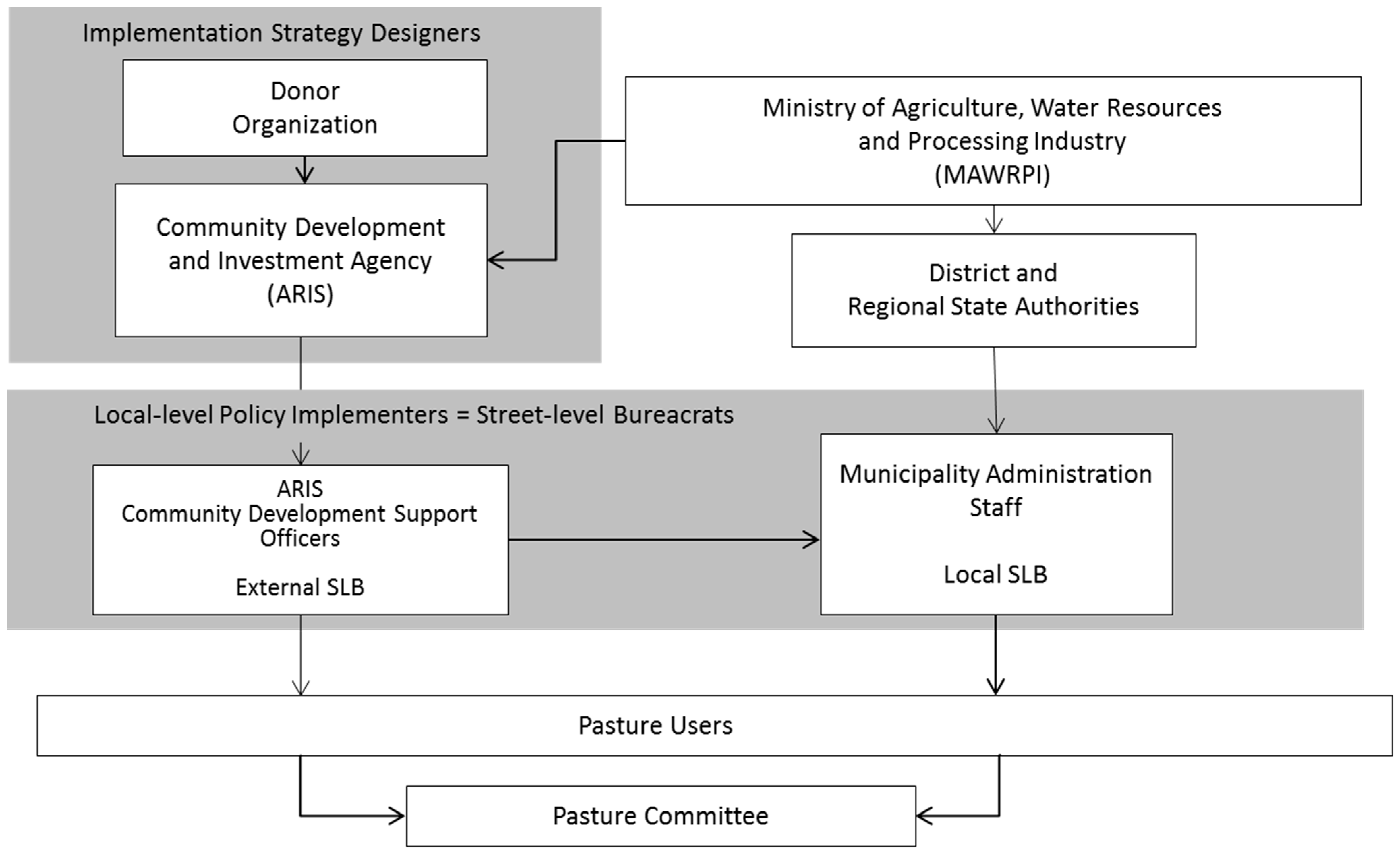

Data collection started with the mapping of the policy implementation network based on a set of expert interviews and document analysis. An overview of the pasture law implementation actor constellation is found in

Figure 2. At the municipality level, two types of SLBs—local and external SLBs—are involved in policy implementation. In the study case, local SLBs are municipality administrators; external SLBs, in contrast, are field staff, called Community Development Support Officers (Community Development Officers) of the law-implementing organization, Kyrgyz Republic’s Community Development and Investment Agency (ARIS). Both actor groups are the lowest-level staff members in hierarchical organizations. Municipality administrations depend on orders of higher authorities within the Kyrgyz administrative system, mainly from district administrations, where local branches of the central state administration are located. The staff of the implementing organization ARIS is clearly bound to its employer, which is financially almost entirely dependent on international donor organizations, mainly the World Bank. Both of these organizations became involved in policy implementation and the information transfer transaction at different points in time. Municipality administrators started implementing the Pasture Law at the municipality level by July 2009. The staff of ARIS supported this process with additional activities from September 2009, onward. This time lag can be explained by a delay in the provision of implementation instructions to municipality administrators by central government bodies in charge of the law design (for details, see [

55]). The exact reason why policy implementation by municipality administrators in Ala Too and Bulak started in July 2009, could not fully be verified. In summer, 2009, members of regional and district branches of the central government informally ordered the start of pasture committee formation. None of the respondents at the municipality level, but also no expert at the district and national levels could remember the exact date and the way in which this was announced. However, as a result of what the head of the municipality of Ala Too named “orders from the government, but at that time, we got different orders”, Ala Too and Bulak both had created a pasture committee, which existed in July 2009, before the ARIS implementation process started. Hence, in all three study municipalities (for the explanation for pasture committee establishment in Kara Tash, see above), pasture committees existed before the ARIS implementation activities started.

I conducted 18 expert interviews [

65] with “policy implementers,” whom I define as individuals who possess, due to their function or their role in the policy implementation process, specific process knowledge about the information transfer transaction. I also interviewed implementation strategy designers, including representatives of: (1) the Ministry of Agriculture; (2) the policy implementing organization ARIS; (3) the municipality administration; and (4) resource users who were given positions in the newly-established pasture committees (

Table 2). In addition, I held background interviews with employees of a Kyrgyz NGO, who consulted the government on pasture law design and implementation. In order to explore the outcomes of the information transfer transaction, I held 47 interviews with purposefully selected pasture users, all of whom owned livestock, but who did not hold any formal office, such as a position within the administration or the pasture committee (

Table 4).

Table 4.

Number of pasture user interviews.

Table 4.

Number of pasture user interviews.

| Case study site | Number of pasture users interviewed |

|---|

| Kara Tash | 12 |

| Bulak | 19 |

| Ala Too | 16 |

Data collection methods were adjusted according to the interview situation. At the national level, semi-structured expert interviews were held. However, respondents at the municipality level considered the research topic very sensitive, so the data collection methods had to be adapted [

66,

67]. Hence, semi-structured interviews were replaced by narrative interviews [

68,

69,

70] in order to minimize the “question threat” [

71] (p. 112f). All interviews were conducted by the author and consecutively translated into either Kyrgyz or Russian.

Interview transcripts were analyzed by means of qualitative content analysis with inductive and deductive coding [

72], combined with stepwise constant comparison [

73,

74]. Deductive coding themes were generated from the framework’s study variables. In addition, the Pasture Law and the ARIS Implementation Plan were reviewed for information related to policy implementation and information transfer prescriptions.

4. Results

4.1. Formal Rules for Implementing a Pasture Management Reform

The following sections focus on how different types of SLBs carried out their task of resource user information and how their actions impacted pasture users’ awareness of CBNRM participation opportunities.

The implementation of the Pasture Law is part of a donor-financed Agricultural Investment and Services Project, which started in 2008. As one component of this project, the MWRAPI had transferred actual implementation activities to the donor-supported Community Development and Investment Agency (ARIS). ARIS employees, so-called Community Development Support Officers (Community Development Officers), were authorized to implement laws at the municipality level starting from August 2009 (

Figure 2).

The first phase of implementation was rather un-coordinated: In spring, 2009, municipality administrators started forming pasture committees without specifications from higher administrative bodies. Only in a secondary phase, from August 2009, on, did ARIS start their implementation operations at the municipality level, for which they designed a detailed implementation plan (ARIS Implementation Plan) with specifications on information dissemination.

The ARIS Implementation Plan prescribed a series of municipality-level information transfer activities as prerequisites for the establishment of pasture committees. The aim was participatory citizen mobilization and involvement of heterogeneous municipality-level actors, including marginalized and minority groups. The ARIS Implementation Plan lists 41 detailed tasks for CBNRM implementation, the responsible bodies, the pasture users to address, the expected results of each task and the relevant instruments. The full procedure is beyond the scope of this article. Therefore, only the prescribed municipality-level activities are summarized in

Table 5 and discussed in the following sections.

At the municipality level, the information campaign comprised the following: (1) roundtables in each district and municipality administration; (2) municipality-level information campaigns, including household-level information activities; (3) introductory meetings at the village level; and (4) first village meetings at the village level. The ARIS Implementation Plan specifically suggests that all meetings and activities involve representatives of all social groups. Particularly for the introductory and first village meeting, the participation of representatives of the entire community was mandatory. During the information campaign, Community Development Officers were responsible for explaining the objectives and strategies of CBNRM implementation in greater detail, both verbally during introductory and village meetings, but also by providing written information material. The ARIS Implementation Plan specifically advises Community Development Officers to use blackboard announcements and other dissemination activities from the household up to village level, including the distribution of written information on the pasture governance reform. The ARIS Implementation Plan required Community Development Officers to cooperate with the municipality administration and “self-motivated” local activists in distributing information to the broader community and to pasture users.

Figure 2.

Pasture law implementation actor constellation in Kyrgyzstan in 2009.

Figure 2.

Pasture law implementation actor constellation in Kyrgyzstan in 2009.

4.2. Governance Structures and Street-Level Bureaucrats at Work

The following section describes the implementation situation at the municipality level. It reviews the working conditions and governance structures under which two identified groups of policy implementers operate: ARIS Community Development Officers and municipality administrators. These groups were professionally involved in implementing the Pasture Law in the first year after its publication.

Table 5.

Community-level information dissemination tasks extracted from implementation guideline document distributed to municipality administrations during roundtable talks by Community Development Officers.

Table 5.

Community-level information dissemination tasks extracted from implementation guideline document distributed to municipality administrations during roundtable talks by Community Development Officers.

| Activity | Key Objectives (Selection) | Resource User Involvement | Citizen Information Strategies |

|---|

| Roundtable talks at the municipality level | Explanation of pasture legislation, Pasture User Union (PUU) and pasture committee objectives, structures and registration procedures, discussion of implementation procedure at the community level, cooperation agreement between municipality administration and implementing agency on social mobilization and implementation. | Invitation of leading staff of the municipality administration, representatives of the village council, specific village interest groups (including women’s groups, youth groups, etc.). | Preliminary meetings with chairpersons of key organizations, written invitation of all participants. |

| Information campaign | Dissemination of printed and verbal information on the pasture management and improvement project. | Farmers (large-scale, small-scale), herders, indirect pasture users, women, elderly council members, youth, low-income households, local community, public and private organizations in households, streets, organizations and villages. | Design of detailed dissemination strategy for households, streets and villages.

Involvement of existing community groups from previous (ARIS) projects. |

| Introductory meetings in each village | Explanation of new legislation on pasture management, PUU and pasture committee objectives, structures and registration procedures, discussion of implementation procedure at the community level, selection of village mobilizers, establishing four pasture user groups ((1) large-scale farmers; (2) small-scale farmers; (3) herders; (4) indirect pasture users), definition of the minimum number of participants for village meetings. | Farmers (large-scale, small-scale), herders, indirect pasture users, women, elderly council members, youth, low-income households, local community, public and private organizations. | Information on dates, times and venues of the introductory meetings is made available to the general public and local organizations during the information campaign. Announcements to be posted in public spots. |

| First village meeting | Additional information on PUU and pasture committee, discussion of PUU charter, approval of pasture user group membership, election of PUU conference delegates, appointment of pasture committee members for the village. | Farmers (large-scale, small-scale), herders, indirect pasture users, women, elderly council members, youth, low-income households, local community, public and private organizations. | Verbal and printed information on the goals and objectives, procedures for the formation of pasture user groups (see introductory meeting for explanation) is disseminated among all of the parties concerned. Flyers describing the goals and objectives of PUGs and procedures for their formation to be posted in public places. Work will be also executed through self-motivated people who are well aware of and willing to participate in the PUGs. |

| Municipality council session | Discussion of PUU charter, appointment of 5 municipality council members for pasture committee. | Municipality council members | |

| PUU foundation conference | Formation of PUU, discussion and approval of pasture committee composition, formation of auditing committee | Delegates and invited parties | Information of delegates on details of the conference |

4.2.1. Municipality Administrators

After the Pasture Law was passed, municipality administrators became responsible for its implementation and for the formation of pasture committees. After August 2009, their status changed, and they effectively became co-implementers of ARIS Community Development Officers and were endowed with an implementation plan that had been drafted by ARIS. This study mainly refers to heads of municipality administrations (municipality administrators) as local SLBs.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, municipality administrators operated in a strict hierarchical system lacking transparency and openness [

75]. Therefore, at the municipality level, the head of the municipality holds a very prominent role within the administration; other municipality administrators—e.g., so-called agricultural specialists—do not play any relevant role and do not hold independent decision making authority, because the head of the municipality usually monitors them very closely. At the same time, the head of the municipality, herself or himself under orders of higher authorities, such as the district administration, regional administration or employees of the line ministry, holds only very limited practical authority for independent decision making [

57,

59,

76,

77]. Nevertheless, my interviews show that in specific situations, as in the study case, there is room for discretionary decision making.

Municipality administrators had to cope with unspecific implementation instructions and external pressure. All interviewed municipality administrators critically pointed to very unspecific orders from higher administrative bodies on implementing the Pasture Law. While all had received access to copies of the Pasture Law in spring, 2009, and had been instructed by pasture committees, no implementation instructions had been provided. Hence, all municipality administrators expressed a lack of information and a need for support and guidance on the implementation of the Pasture Law. In one municipality, the interviewed administrator even asked me for my own knowledge about ongoing implementation in other municipalities. He said he expected insights into the proper implementation of the Pasture Law.

Despite the initial pressure for implementation, interviews revealed that municipality administrators’ actual implementation of the Pasture Law was not monitored by higher administrative staff. This caused large room for discretionary decision making and also insecurity and uncertainty. Hence, information gaps and large discretionary power led municipality administrations, in the manner of SLBs, to use their own version of appropriate procedures for resource user information and pasture committee establishment.

Throughout the first year of the implementation process, municipality administrators did not gain a full understanding of the concept of CBNRM as a form of participatory resource user self-governance. Although, from August, 2009, ARIS Community Development Officers introduced the ARIS Implementation Plan to municipality administrators to fill information gaps on the expected process of Pasture Law implementation; CBNRM-related training was not provided. Therefore, municipality administrators’ information on the concepts of CBNRM remained very vague. The importance of resource user mobilization and participatory aspects of CBNRM in general did not reach municipality administrations. As will be shown later, this impacted how municipality administrators performed the information transaction.

4.2.2. Community Development Officers

ARIS Community Development Officers are external SLBs, who became the responsible municipality-level policy implementers for local information activities from August 2009, onward. They were instructed to carry out time-consuming information transfer activities prescribed by the ARIS Implementation Plan and also had a very tight timeframe to execute their task. On the other hand, there was some room for discretion due to low enforcement and lack of regulations for some of the challenges that emerged from cooperation with municipality administrators.

As employees of ARIS, Community Development Officers were introduced to the detailed ARIS Implementation Plan (

Table 5) during a one-week training workshop. As a result of this training, Community Development Officers considered municipality participation during the entire CBNRM establishment process critical for success and, therefore, a desirable objective for municipality-level activities. All interviewed Community Development Officers shared a common task perception: they claimed as their objective to ensure an understanding of CBNRM objectives among all municipality residents and to ensure the involvement of all pasture users in CBNRM. However, as will be shown below, this ideal task perception deviated from their actual task performance.

Community Development Officers worked under considerable time pressure, which motivated them to use their right to rely on support from municipality administrators for the information transfer transaction. Their time plan gave them only about eight weeks to establish a pasture committee. Hence, they were effectively unable to perform the information tasks prescribed in the ARIS Implementation Plan, which included: (1) street-level and household-level information dissemination; (2) delivery of written invitations to participants in the roundtable meetings at the municipality level; and (3) inclusion of defined minority groups in all implementation activities. Consequently, they transferred these activities to the municipality administrators.

Community Development Officers had to cope with incomplete and inadequate implementation rules. The ARIS Implementation Plan did not provide rules for the management of cases that deviated from the expected situation, but such cases were found in all studied municipalities. One example is that upon their arrival, Community Development Officers found pasture committees that had earlier been established by municipality administrations and violated the sequence of required action and citizen participation prescribed by the ARIS Implementation Plan. Community Development Officers were therefore informally instructed by their employing organization ARIS to dissolve such non-participatory pasture committees and to restart Pasture Law implementation according to the ARIS Implementation Plan. However, ARIS did not provide formal process requirements on dissolving existing pasture committees and tools for participation evaluation. This left considerable room for discretion. Another observed effect of incomplete rules by ARIS was that Community Development Officers lost control of information transfer activities that they had delegated to municipality administrators. Community Development Officers neither possessed the means to evaluate the information activities that they shifted to municipality administrators, nor did they hold any formal rights to enforce specific tasks, because they were not members of the higher administration to which municipality administrators effectively report. Hence, the municipality administrations possessed wide discretion regarding the degree of citizen involvement and followed their own perceptions of adequate citizen involvement and information procedures (see

Section 4.2.1).

Furthermore, the prescribed time plan was inadequate with respect to pasture users’ needs and implementers’ capacities. A static and overloaded process schedule put Community Development Officers under substantial time pressure. In their opinion, the prescribed procedure did not acknowledge local time preferences and was not adjusted to the pasture users’ capacities and needs.

First, the information campaign and pasture committee formation were to take place during the yearly migration season, when an important group of pasture users, the migrating herder families, were absent from the villages.

Interviewer: Interviewer: “Do you have a specific plan by when you expect to have pasture committees registered?”

Respondent “By October 10, we were told.”

Interviewer “Do you think that is realistic?”

Respondent “No, because we were on the training course in Bishkek in August, where we discussed the first component of the project, and there we were given this date. But we also suggested starting it only after November 10.”

Interviewer: “To start?”

Respondent: “To start, yes, because you know that all herdsmen are in the mountains right now, and we have few people here in the village.”

Second, the ARIS Implementation Plan required a number of meetings that was assumed to overstretch the capacity of the usually small group of municipality residents who tend to be involved in self-governance activities. Given that municipality administrations had formed pasture committees already, Community Development Officers considered the obvious replication of implementation activities to contradict the objective of broad resource user mobilization. Community Development Officers feared that duplicate meetings would demobilize potentially interested municipality members, because those who engage in municipality-level self-governance activities are usually asked by the municipality administration and other community members to participate in many of the existing self-governance committees, such as the community development committee, irrigation water committee, drinking water committee, and the like.

“We already told [ARIS] that there is no need for the information meeting, because we have a lot of meetings. We have subcomponents for which we have to hold different meetings, and usually, the same people come to the meetings, and they are already fed up with the meetings. That’s why we suggested not to hold this information meeting, but to have only one meeting, the first one, where we can give general information. […] Our management also supported our suggestion not to hold so many meetings. We thought that we could just combine the information meeting with the pasture user groups and the first meeting. All this could be one procedure.” (Community Development Officer).

The following quote illustrates an additional challenge from the ARIS Implementation Plan. The plan held inadequate assumptions about resource users’ interest in self-governance activities. ARIS counted on “self-motivated people” willing to engage in implementation, but the mobilization of pasture users was difficult.

One member of a pasture committee described his situation as follows:

“My wife is already very angry with me because I keep spending so much time with working for the community. I am always being asked to do more tasks. I have to pay for everything myself: paper, stamps, etc. She says that I should stop spending all my time for the community, because I do not get anything.” (Kara Tash Village, pasture committee member).

Furthermore, ARIS did not reward the commitment of Community Development Officers for full resource user involvement, but insisted on plan fulfilment, while accepting low levels of participation. All interviewed Community Development Officers questioned the adequacy of the strict timeframe for pasture committee registration, which they considered to impact negatively upon resource user involvement. An initiative by Community Development Officers to modify the ARIS Implementation Plan to better meet citizens’ capacities and needs, such as holding municipality meetings at a time of the year when the pastures users, most of them pastoralists, were actually present in the village, was not acknowledged by ARIS management. Instead, ARIS management encouraged the Community Development Officers to focus on registering pasture committees within the prescribed deadline.

Interviews revealed that ARIS management staff had in fact abandoned the objective of reaching full municipality information by means of the prescribed measures in the ARIS Implementation Plan:

“[…] our staff [Community Development Officers] also cannot give information to everyone [in the municipality]. Of course it will take time. When the members of the pasture committee come to the house and collect payments, like the electrician for electricity, then people will maybe understand everything about the [pasture] law. I think in one or two years, everybody will know about the pasture law, payment and taxes.” (Representative of ARIS).

4.3. Outcomes of the Information Campaign

The impact of the created information working rules on pasture users’ awareness of opportunities to participate in CBNRM was studied by means of 47 pasture user interviews. The analysis showed a very limited impact of the mainly municipality-run information dissemination activities by October 2009, when the pasture committees were to be officially registered.

Most respondents claimed to be informed about the existence of a Pasture Law; however, this knowledge was very vague and incomplete. Both groups, those who claimed to know about the law and, interestingly, also those who said they knew nothing, had a very incomplete understanding of its content. It was a surprise that several respondents who claimed to know nothing about any legal change were aware of at least some details of the CBNRM reform, such as the abandonment of rental payments for pastures and a decentralization of management authority.

Respondents were not aware of the future importance of the pasture committee in distributing pasture access rights and regulating the amount and spending of pasture user fees, to name some tasks. Some kind of pasture committee existed in all municipalities. Of all respondents, ten claimed to know the head of the municipality pasture committee. Only three among all respondents believed, correctly, that the pasture committee was the new responsible body for pasture management.

Participation opportunities were largely unknown to pasture users. First, not one respondent was aware of the existence of a Pasture User Union, of which, according to the law, all municipality residents are members. Neither did anyone know about the associated election rights for pasture users or any participation opportunities. Furthermore, no respondent embraced the idea that the Pasture Law had shifted pasture management and administration rights from state bodies to pasture users. Second, membership in the pasture committee was considered a privilege for selected community members. Those who had heard about the possibility to become a member in a pasture committee assumed that this membership was not open to “average or poor people”, but only to “the active people”, “educated people”, the wealthy and owners of large herds or members of the local elected community council. Furthermore, none of the respondents were aware of any future information transfer activities at the time that the interviews were held. This was particularly striking in the municipality of Kara Tash, where, according to information provided by the Community Development Officers, the introductory village meeting was to be held three days after the interviews; still, none of the interview partners had heard of this upcoming meeting.

The formal information campaign had not been a relevant channel of information dissemination.

Table 6 shows that informal information transfer proved more effective than formal information transfer and that the majority of those respondents, who claimed to be aware of a new law on pasture, had received information via other channels. Only one interviewed non-office holder had participated in an information meeting on pasture management.

Table 6.

Respondents’ sources of community-based natural resource management (CBNRM)-related information.

Table 6.

Respondents’ sources of community-based natural resource management (CBNRM)-related information.

| | Ala Too | Bulak | Kara Tash | Total |

|---|

| Awareness of Pasture Law | | | | |

| No | 6 | 14 | 6 | 26 |

| Yes | 10 | 14 | 6 | 30 |

| Source of information | | | | |

| Paper | 1 | - | 1 | 2 |

| Radio | - | - | 2 | 2 |

| Television | 1 | 3 | - | 4 |

| Neighbor/family member | 7 | 7 | 1 | 15 |

| Municipality administration | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Municipality council | - | - | - | - |

| Meeting at the municipality/village level | - | 1 | - | 1 |

In all municipalities, information transfer was obviously not inclusive and did not aim to reach the broader community. The interviews indicated that relevant and consistent information reached either only those individuals or families who maintain a tight relationship with the municipality administration or local activists or those who were chosen for participation in the process of pasture committee establishment. The three respondents who were aware of the future role of the pasture committee were in fact relatives of the head of the administration or relatives of those who were designated pasture committee members, such as the father of a pasture committee member and a livestock expert, who the municipality administration had invited to become a member in the pasture committee, though he had not accepted.

The interviews showed that the information channels used completely circumvented families and individuals who were not part of the communication network of those who had been selected for participation in CBNRM implementation. A case that exemplifies the lack of trickling-down of information or the use of neutral information channels are two neighbors in the municipality of Ala Too: while the sister of the head of the administration was by far the best-informed interviewed non-office holder among all respondents, her neighbor, a forty-five-year-old male herder, was not aware of any legal changes in pasture management.

4.4. Working Rules for Resource User Mobilization

Low resource user involvement resulted from incomplete information transfer as a result of the simplification of the implementation tasks by both types of SLBs: the Community Development Officers and the municipality administrators.

4.5. Determinants of Working Rule Design

Due to time pressure and a lack of familiarity with the local conditions, Community Development Officers of the government-mandated implementing organization ARIS shifted the information campaign task to municipality administrators. Municipality administrators, however, ignored the prescribed public information campaign, which included public announcement of information meetings and distribution of information material specified by ARIS. Instead, municipality administrators selected pasture experts, honorable members of the community and their closer network and invited them for upcoming meetings and potential participation in the planned CBNRM self-governance organization, called the pasture committee.

While this might be considered a strategy for rent seeking, I propose a different explanation: The responsibility for the information campaign was shifted from Community Development Officers, who had received training on CBNRM and, therefore, knew the relevance of the resource user information campaign, to municipality administrators, who had only received implementation information from Community Development Officers, but lacked any further training on CBNRM principles. Hence, municipality administrators in charge of the information campaign held a different perception of the required information dissemination activities. By contacting only those members of the community who they deemed to possess the relevant expertise and influence, they followed a previously used, non-participatory, but rational strategy. They selected people who they considered qualified for self-governance. This has to be seen as an existing local governance practice. It meets (at least) administrators’ perceptions of adequate transparency and accountability, according to which primarily those who will effectively manage the pastures—the potential pasture committee members—qualify for information access. This working rule, however, led to task performance that was non-participatory and sometimes clandestine.

The shift of responsibility for the information campaign was not accompanied by adequate steering by Community Development Officers for a number of reasons: First, they lacked time to monitor and control the performance of the information campaign. Second, there was a lack of formal rules and a means for enforcing the execution of information activities to regulate the cooperation between municipality administrators—basically, members of the state administration—and Community Development Officers, who are employees of a government-mandated and donor-financed organization. Hence, municipality administrators are not formally accountable, neither to the Community Development Officers, nor to ARIS as an organization. Third, Community Development Officers’ motivation for improving the quality of the information campaign abated after they recognized that ARIS showed little interest in the campaign. As discussed in

Section 4.2.2, ARIS did not effectively support the proposed modification of rules for improving the outreach of the information campaign, as proposed by the Community Development Officers. Instead, ARIS encouraged them to meet the deadline for pasture committee formation in any case. My interpretation is that ARIS’ denial of the Community Development Officers’ request to adapt the dissemination strategy to municipality needs first made officers perceive their agency’s main interest to be the timely formation of pasture committees instead of municipality information and, second, led to some degree of frustration and, therefore, made officers prefer to invest their limited time in the establishment of pasture committees, as preferred by ARIS, instead of sharing information about CBNRM principles with resource users.

Community Development Officers therefore enforced those participation requirements for pasture committee membership that were easy to observe and control, such as the minimum number of members or the participation of municipality council members.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

I aimed to answer how and which information rules are designed for community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) during the implementation of a pasture management reform in Kyrgyzstan, and how they impact the distribution of CBNRM-related information. The research was motivated by an interest in filling a knowledge gap on the determinants of the distribution of CBNRM-related benefits at the resource user level, which has been linked to access to information and participation opportunities.

My data show that information working rules were designed by the staff of a policy implementing organization in cooperation with municipality-level administrators. In contrast with implementing agency regulations, which aimed at the participation of all pasture users in CBNRM (albeit, in different roles), the designed information rules limited information access on CBNRM participation opportunities to resource users hand-picked by municipality-level administrators.

My study found difficult working conditions for both the staff of the policy implementing organization and municipality administrators, who, to a large degree, were impacted by the governance structures to whom they reported. They had to cope with: (1) an initially uncoordinated implementation process; (2) unclear distribution of competencies; and (3) delayed provision of insufficiently tailored implementation rules, designed by the implementing organization, not its local staff. This has motivated the staff of the implementing agency to develop routines that aligned their own tasks with the available capacity and time and likewise satisfied the implementing organizations. These routines—the actual information working rules—however, did not contribute to resource users’ awareness of CBNRM participation opportunities. There are two reasons for this: (1) municipality administrators adopted information working rules that they considered most successful and that consisted of informing only a few instead of all resource users; (2) the staff of the implementing organization ignored their agency’s sub-goal of ensuring full resource user participation and largely accepted the working rules created by municipality administrators.

This article explains the information working rule design for the donor-initiated policy implementation transaction as an unintentional effect that emerged from lowest-level policy implementers bounded rational [

53] choice of routines to cope with difficulties and ambiguities in task prescriptions received from their agency. The developed routines serve to achieve satisfaction instead of optimization of decisions and processes. Satisficing led to the emergence of information rules that did not guarantee reaching the donors’ stated participation goals, but allowed to keep the timeline prescribed by the agency.

These findings pose theoretical implications. First, rule design motivated by satisficing leads to institutional persistence instead of institutional change. In the study case, the staff of the implementing agency (to which no formal accountability relationship existed, but to whom municipality administrators felt accountable due to the agency’s proximity to the central government and donors), in order to avoid difficult and time-consuming enforcement of agency rules, was satisfied with information working rules set by the municipality administrators. Municipality administrators, also in order to avoid time-consuming and potentially conflict-bearing full resource user involvement, employed non-participatory, non-inclusive information rules inherited from the Soviet period. In effect, in the study case, satisficing encourages institutional persistence (in other words, path dependency) and hinders institutional change.

Second, the findings are in contrast to the perceptions of institutional competition or rent seeking theory, according to which actors would intentionally design rules that exclude others in order to increase their individual benefits. In the study case, rent-seeking does not play a role. This is, however, not a surprise, as at the time of data collection—a very early phase of CBNRM implementation in the pasture sector—those in charge of working rule design could not anticipate the potential economic rents associated with participation or non-participation in CBNRM. In 2009, municipality administrators, on the one hand, had no information on rules for fee collection, resource access nor other potential economic implications of CBNRM for the pasture sector in Kyrgyzstan. On the other hand, Community Development Officers, as non-local external staff members of a non-local organization, did not entertain economic relationships with municipality residents and local pasture users. Rent seeking, however, might, under different circumstances, e.g., once the full potential of pasture committees is understood, become a motivation for rule design.

The analytical framework was well suited to structure the data collection and analysis. The specifications of the actor-governance relationship that I introduced with the concept of street-level bureaucracy helped to explore a very important relationship in rule design during policy implementation processes, which is often not explored. The framework is suited for studying a link between governance structures and working rule design, which has not been studied often. It offers an explanation for actors’ method of action selection, which is well accepted in public administration theory, but has to date not received much attention in institutional analysis. The study therefore revealed the impact that governance structures, via their procedural regulations and practices, have on working rule design. It helps to study those only implicit relationships and mechanisms by which governance structures impact actors’ behavior.

The application of the framework is nevertheless a challenge. Each of the framework’s elements requires extensive background research (legal reviews, exploring and mapping of actor networks, study of actor characteristics at different administrative levels, exploration of governance structures and the linkages between these elements), which is only possible by using in-depth case studies that use qualitative research methods combined with other data collection methods. Such a data collection strategy is time consuming and requires substantial funding. Besides, research on the characteristics of governance structures is risky, particularly in environments where governance structures are intentionally opaque. In such environments, rules of conduct are difficult to understand, and respondents might hesitate to reveal insights into ongoing governance practices. Hence, there is a risk that substantial data gaps might remain, which endanger the success of the research process.

This leads to a further limitation of the study. The present study reports on the first year after the proclamation of the Pasture Law, which was characterized by confusion about the adequate implementation on all administrative levels. Therefore, the study’s findings about very low levels of resource user information require careful interpretation, and it is very likely that different sorts of information transfer have occurred, which have greatly increased the awareness of the pasture management reform.

The study has practical implications for CBNRM implementation design. The findings emphasize that implementation and information transfer, in particular, as well as the goal of active resource user participation require a well-designed, time-consuming strategy. Strategies based on blueprint perceptions of simple, local, informal information transfer or an assumed automatism according to which information, once provided to a limited number of people, quickly spreads to all members of the resource user group, including minorities and vulnerable segments of the population, are insufficient. Similarly incorrect is the assumption that resource users are eager to participate in municipality-level activities. The local situation is, instead, that only a small group of actors with limited capacity, voluntarily or under pressure, assumes offices. Therefore, careful planning and full acknowledgement of local policy implementers’ roles, resources and perceptions of reward structures, as well as resource users’ capacities and interests are required to create effective implementation strategies. Implementation strategies must encompass trainings to ensure a complete understanding and acceptance of all objectives, including intermediary objectives, such as full resource user awareness of ongoing changes, among implementers at all hierarchy levels, but particularly among those working at the service frontline. The strategy must cover rules that are complementary to the working environment of local policy implementers. Designers of implementation strategies need an understanding of decision making among implementation actors. The study’s findings clearly point out the need to fully acknowledge implementation contexts. Therefore, the design of implementation strategies must be preceded by a review of the hierarchical relationships of CBNRM policy implementers, including those among different layers of the administrative system, in order to develop meaningful monitoring and enforcement mechanisms that go beyond command and control, but allow for a meaningful evaluation of participatory activities. There is, in addition, a need to review existing information channels by means of which different groups at the specific municipality level can be reached. Information on resource users’ time resources, availability and capacity for participation is also needed. It is obvious that local policy implementers play a key role as sources of information. However, they should also participate in designing meaningful rules and tools for CBNRM implementation.