1. Introduction

The very purpose of student evaluations of teaching (SET) is to provide colleges with basic information to improve the quality of education [

1] as well as for the instructor to improve in their teaching discipline. Hence, it can be argued that students’ indifference to teaching evaluations results in a lack of fair assessments of the instructors’ productivity, which perhaps undermines the sustainability of the educational evaluation system (When a semester is completed, every student has the opportunity to evaluate whether the original syllabus in all classes was correctly completed, if the instructor was suitably prepared for classes, or if any improvements could be made. This evaluation can be reported as part of the instructor’s achievement evaluations, and could be useful for generating information for registration in the next semester). Students’ thinking patterns, behavior, and lifestyle can be negatively affected if the students adopt a careless or indifferent attitude toward the evaluation. For example, monotonic response (MR) patterns, which are typical examples of student indifference to teaching evaluation, are shown to be the result of an uncooperative attitude (noncooperation), surpassing the cost-benefit level of the individual, for the purpose of presenting an objective evaluation to other students who will take the class or the instructor; therefore, this incurs costs for organizations while the students reduce their time costs. This behavior by students may be penalized in the labor market by lower employability. If students recognize this penalty in advance, then their incentive to be indifferent is weakened, and hence the soundness of the SET system may be maintained.

There has always been a degree of asymmetric information between employers and potential employees that is lost in job marketing signaling because certain hidden characteristics of college graduates are not included in their “specs” (In South Korea, “specs” is an abbreviation for “specifications”, and is used as a word that sums up education, including GPA, language scores, and qualifications, among those seeking employment) [

2]. Although specs could be representative of the potential job ability of employees, it has many limitations as a proxy variable for the important factors that influence actual job achievements when performing at work, such as personal characteristics of personality, interests, and human nature, which cannot be converted into values and records. As a result, firms have been modifying job interviews to screen for their applicants’ hidden characteristics through the utilization of various personality assessment models (e.g., the Big Five personality traits) for managing employees (The Big Five personality traits refer to five broad dimensions used to describe human personality. The five factors have been labelled: extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience, which is a summary of the common features shown by the most socially successful people in specific working environments. The big five personality traits incorporate results from various groups, including different cultures, and are explained by various tools and theoretical frames [

3,

4,

5,

6]). However, there has been criticism regarding whether the screening process is properly performed [

7].

Previous studies have analyzed the effects of curriculum and non-curriculum activities on employment. Through analysis of the effects on salary after university graduates gain employment in the USA, Arcidiacono [

8] explained that SAT scores and GPA are the main factors that determine future achievements in the labor market, while Lassibille

et al. [

9] reported that students in college who attended irregular academic programs for employment had reduced periods of unemployment. However, limited research has been conducted on how the use of employment prestige is affected by students’ unseen personality traits, revealed through campus life habits, such as behavioral patterns in teaching evaluations, because of the difficulty of collecting data on those personality factors.

Even with a great deal of sources, there are few variables that account for personal behaviors, personalities, and psychological characteristics. Accordingly, studies dealing with personal tendencies and psychology are mostly dependent on surveys that measure potential factors of personal traits; however, behavior in real environments can provide representative information about personality [

10]. Mischel [

11] mentioned that personal traits are manifested completely under specific circumstances, and that these traits can be identified through personal behaviors in specific situations during college, such as in responses on student evaluations of teaching (SET). The validity of the items in the SET is considered to be reasonably good, as the items have been verified by experts for several years and similar items are widely used in Korean universities. Also, a number of studies have analyzed and confirmed the validity of SET. SET constitutes measurements of teaching effectiveness [

12], and illustrates the relationships between ratings of teaching effectiveness and other variables related to different dimensions or factors of students’ evaluations [

13,

14]. The studies on SET explore the validity and reliability of student opinions and offer suggestions aimed at improving instruction.

Thus, this study uses the students’ responses to educational assessments as a proxy variable for personality. To encourage students to participate in SET, most universities allow only those students who have completed the SET to check their grades and raise objections during grade announcements. However, some students choose the same answers to every question in the SET. This pattern of identical answers to all questions on the SET is called the monotonic response (MR). This study substantially provides the link between MR and personality traits, and how a student’s personality, which is reflected in their behavioral patterns in SET, influences employability.

This paper is organized as follows. The next section describes the theoretical framework for this analysis.

Section 3 contains a literature review of MR and the five-factor model of personality and employability.

Section 4 provides a summary of the data used herein, and the empirical models. The results are reported in

Section 5, followed by the conclusion in

Section 6.

2. Theoretical Framework

What reasons or incentives motivate students to engage in MR? First, those that select the same number for all of the questions in SET, rather than carefully reading each question before responding, can reduce the time cost required to check their grades, which is beneficial. Especially, if students have a high time cost opportunity, they could answer all items equally on the evaluation and save time in order to invest it in other valuable ventures. This behavior may correspond with what is considered a kind of cost-benefit rationality in economics. In a similar vein, Choi and Kim [

15] explained that selecting the same numbers for each response does not necessarily indicate insincerity by the student.

MR could also be due to insincere responses made without understanding the purpose of individual questions, and without reading the questions carefully. This could have a negative effect when the focus is on organizations and contributions to teamwork. As a result, it can be considered a negative factor for demonstrating productivity in the labor market.

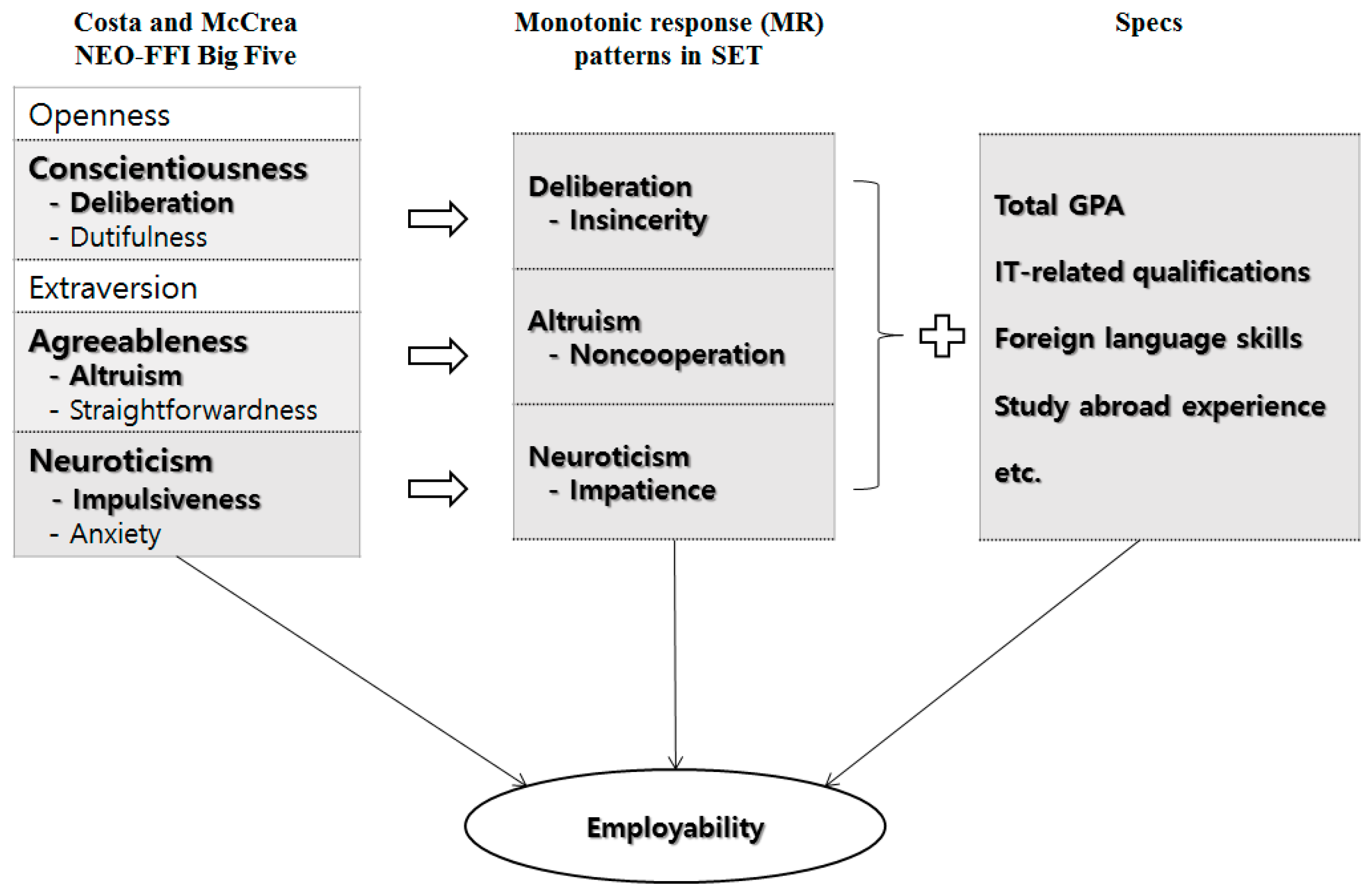

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework for the impact of students’ personality in SET and their specs on employability. The image relates the personal traits derived from MR to the big five personality traits (Big Five), which are well known as the most comprehensive and confidential analysis frame for recruits and HR management [

16].

The Big Five personality model in

Figure 1 shows five items for recruiting preferable candidates, and corresponds to the traditional norms of HR management [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Costa and McCrae [

18] and John and Srivastava [

21] presented evidence that most of the variables used to assess personality in the field of personality psychology can be mapped to one or more of the dimensions of the Big Five. In this study, we hypothesized that three personality constructs, “conscientiousness”, “agreeableness”, and “neuroticism”, would be related to MR.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for the impact of students’ personality in SET (student evaluations of teaching) and specs on employability.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for the impact of students’ personality in SET (student evaluations of teaching) and specs on employability.

The Big Five describes conscientiousness as a sense of responsibility, orderliness, dutifulness, self-discipline, and deliberation. In this respect, MR could be an indicator of a sense of responsibility to faithfully respond as students, even though responding to the student evaluation is not mandatory. Also, MR measures whether individuals themselves participate as members of an organization by providing the right information to other students or the instructor. SET aims to improve the quality of education through an objective assessment of students’ classes or instructors. Conscientiousness, which has most consistently emerged as the Big Five construct related to performance across jobs [

22,

23], is related to deliberation by an individual. The Big Five suggests that a sincere person who performs given tasks responsibly due to “conscientiousness” also has the property of deliberation and dutifulness.

Altruism and straightforwardness are sub-properties of “agreeableness” [

18]. Agreeable persons are also cooperative (caring of others), representing the agreeableness factor in the Big Five. MR shows a tendency toward more non-cooperative and selfish behavior, which falls agreeableness in the Big Five. If MR is considered to be a disabling act to reduce the cost opportunity for time in the respect of evaluation systems to improve the education quality in college, then this indicates the opposite of altruism, meaning

noncooperation with organization regulations. Also, by reflecting the student’s desire to view their grades after providing quick evaluations, it signals the

insincerity property which goes against deliberation. The other factors from the Big Five, such as dutifulness or straightforwardness, can also be found indirectly through the linkage of MR.

Neuroticism in the Big Five is also related to MR. According to Costa and McCrae [

18], the neuroticism dimension assesses adjustment or emotional stability

versus maladjustment or neuroticism. Impatience is explained as a characteristic of neuroticism in addition to impulsiveness and anxiety [

24]. The act of providing a quick evaluation by answering all items equally could be described as impatience. A few studies have found negative associations between impatience and labor market outcomes [

25,

26]. This relation has been most often interpreted in terms of the debilitating effects of anxiety [

27], and impatient individuals are thought to experience anxiety, impairing their performance.

Thus, MR is hypothesized to be a good measure of graduates’ personalities. In the analysis, we also consider spec-related variables, which reflect the graduates’ academic abilities or human capital such as total GPA, IT-related qualifications, foreign language skills, study abroad experience, etc.

It is still under theoretical dispute whether MR can have a positive or negative effect on the employability of students in the labor market, but this study attempted to measure which influences are stronger through substantial analysis. If either the positive or negative elements have a significant influence, then it will provide important evidence that recruiters should not be dependent solely on specs like GPA [

3]. Accordingly, by applying various models for the substantial analysis, such as Logit, Multinomial Logit, and Tobit, this study sought to determine whether MR frequency during the college years may influence employability and employment prestige in a specific period.

5. Main Results

The results of analysis of the Logit and Multinomial Logit models, regarding the employability of the college graduates are presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Model 1 of

Table 4 presents the results of Logit analysis, with the employee encoded as the dummy variable 1. Model 2 and

Table 5 indicate the results of Multinomial Logit after categorizing the orders based on the sales, net profits of the year, and average annual wages of the firms. Logit analysis revealed that the ratio of MR had a negative effect on employment. In addition,

Table 4 and

Table 5 show that once other variables were controlled, the ratio of MR has a significantly negative effect on the probability of work in top 50, middle, or low ranked firms. The Multinomial Logit indicated that the marginal effect of the MR variable on employees in the top 50 firms was

exp(−0.503) = 0.605. This means that the probability of employment in the top 50 firms was estimated to decrease by 60.5%, compared with non-employees, when the ratio of MR increased by one unit. In addition, the probability of being employed in the low-ranked firms decreased to 71.3%.

Therefore, those with higher MR on the SET for each course were less likely to be employed than those who did not. In addition, they were more likely to start work at firms whose sales, net profits, and average annual wages were lower. Barrick and Mount [

17] claim that conscientiousness was significantly related to job performance, and the validity of agreeableness was also negatively correlated. In addition, some studies demonstrate that impatience is negatively related to labor market outcomes [

25,

26]. Consistent with our assumption about the association with MR, these previous studies support the validity of our results. Although MR does not necessarily indicate the student’s insincerity, it has a negative effect, highlighting parameters like

insincerity, noncooperation, and

impatience within the personality traits related to MR. Furthermore, most firms recognize that leadership, an upright personality, and patience play an important role in facilitating a good team environment and job performance. So, they tend to use personality tests for personnel selection before and after hiring people. Personality traits, such as deliberation, straightforwardness, altruism, and impatience, which are revealed through the response patterns of individuals while completing the course evaluations, can be described using the big five personality traits. The results of the analysis demonstrated that those personality traits influence employability.

Table 4.

Logit and Multinomial Logit estimates of employment and employment prestige.

Table 4.

Logit and Multinomial Logit estimates of employment and employment prestige.

| | Model 1 (Employed = 1) | Model 2 (Sales of the Firms) |

|---|

| | | Top 50 Firms | Middle Rank | Low Rank |

|---|

| Graduates’ personality | | | | |

| Ratio of MR | −0.311 *** | −0.503 ** | −0.194 | −0.338 ** |

| (0.091) | (0.159) | (0.121) | (0.113) |

| Graduates’ characteristics | | | | |

| Female student | −0.277 *** | −0.066 | −0.331 *** | −0.310 *** |

| (0.057) | (0.107) | (0.079) | (0.069) |

| Student’s age | 0.067 *** | 0.019 | 0.083 *** | 0.071 *** |

| (0.014) | (0.030) | (0.019) | (0.016) |

| Specialized high school | 0.157 | 0.386 ** | 0.076 | 0.121 |

| (0.111) | (0.193) | (0.155) | (0.132) |

| Seoul | 0.014 | −0.156 | 0.052 | 0.051 |

| (0.053) | (0.096) | (0.072) | (0.065) |

| Metropolitan | 0.196 ** | 0.084 | 0.173* | 0.268 ** |

| (0.073) | (0.119) | (0.097) | (0.091) |

| Special admission | 0.245 *** | 0.271 ** | 0.367 *** | 0.148 * |

| (0.062) | (0.105) | (0.082) | (0.076) |

| Graduates’ spec | | | | |

| Total GPA | 0.162 ** | 0.352 ** | 0.181 ** | 0.107 |

| (0.065) | (0.120) | (0.090) | (0.079) |

| Study abroad participation | 0.777 *** | 0.505 ** | 0.987 *** | 0.659 ** |

| (0.164) | (0.246) | (0.191) | (0.201) |

| IT master certification | 0.290 *** | 0.344 *** | 0.370 *** | 0.218 *** |

| (0.050) | (0.086) | (0.067) | (0.061) |

| Advanced foreign language certification | 0.454 *** | 0.475 *** | 0.698 *** | 0.296 *** |

| (0.068) | (0.123) | (0.088) | (0.081) |

| Double major | 0.241 *** | 0.020 | 0.255 ** | 0.267 *** |

| (0.069) | (0.167) | (0.099) | (0.078) |

| Field of study | | | | |

| Business/Economics | 0.106 | −0.926 *** | −0.308 ** | 0.898 *** |

| (0.080) | (0.148) | (0.101) | (0.098) |

| Humanities/Education | −0.695 *** | −2.244 *** | −1.284 *** | 0.250 ** |

| (0.082) | (0.194) | (0.114) | (0.101) |

| Social science | −1.047 *** | −2.626 *** | −1.821 *** | −0.035 |

| (0.082) | (0.226) | (0.126) | (0.101) |

| Science/Bioengineering | −1.429 *** | −2.297 *** | −1.838 *** | −0.652 *** |

| (0.093) | (0.207) | (0.137) | (0.120) |

| Information | −0.040 | 0.611 *** | −0.406 *** | −0.374 ** |

| (0.081) | (0.105) | (0.103) | (0.125) |

| Year of graduation | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.168 *** | 0.149 *** |

| Observations | 9,083 | 9,083 |

Table 5.

Multinomial Logit estimates of employment and employment prestige.

Table 5.

Multinomial Logit estimates of employment and employment prestige.

| | Model 3 (Net Profits) | Model 4 (Average Annual Wages) |

|---|

| | Top 50 | Middle | Low | Top 50 | Middle | Low |

|---|

| Ratio of MR | −0.451 ** | −0.249 | −0.296 ** | −0.431 ** | −0.297 ** | −0.286 ** |

| (0.156) | (0.156) | (0.101) | (0.164) | (0.128) | (0.108) |

| Total GPA | 0.475 *** | 0.382 ** | 0.041 | 0.543 *** | −0.027 | 0.168 ** |

| (0.118) | (0.117) | (0.072) | (0.129) | (0.096) | (0.075) |

| Study abroad participation | 0.609 ** | 1.002 *** | 0.729 *** | 0.493 * | 0.878 *** | 0.756 *** |

| (0.238) | (0.224) | (0.179) | (0.278) | (0.199) | (0.183) |

| IT master certification | 0.313 *** | 0.317 *** | 0.280 *** | 0.399 *** | 0.398 *** | 0.219 *** |

| (0.085) | (0.085) | (0.055) | (0.093) | (0.071) | (0.058) |

| Advanced language certification | 0.580 *** | 0.666 *** | 0.377 *** | 0.493 *** | 0.540 *** | 0.414 *** |

| (0.117) | (0.109) | (0.075) | (0.137) | (0.098) | (0.075) |

| Business/Economics | −0.817 *** | −0.312 ** | 0.500 *** | −0.195 | −0.580 *** | 0.674 *** |

| (0.140) | (0.127) | (0.088) | (0.141) | (0.110) | (0.093) |

| Humanities/Education | −2.165 *** | −1.236 *** | −0.210 ** | −1.626 *** | −1.612 *** | −0.027 |

| (0.188) | (0.146) | (0.091) | (0.221) | (0.130) | (0.094) |

| Social science | −2.575 *** | −1.676 *** | −0.548 *** | −2.043 *** | −2.061 *** | −0.309 ** |

| (0.218) | (0.161) | (0.091) | (0.220) | (0.142) | (0.096) |

| Science/Bioengineering | −2.155 *** | −2.057 *** | −1.014 *** | −2.348 *** | −2.062 *** | −0.794 *** |

| (0.191) | (0.196) | (0.106) | (0.264) | (0.154) | (0.110) |

| Information | 0.429 *** | −0.434 *** | −0.220 ** | 0.388 *** | −0.103 | −0.401 *** |

| (0.105) | (0.131) | (0.098) | (0.116) | (0.099) | (0.117) |

| Year of graduation | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.138 *** | 0.178 *** |

| Observations | 9083 | 9083 |

Those who had higher IT and language skills were more likely to work for firms with higher sales, net profits, and annual average wages, compared with the unemployed. Participation in programs or student exchange experience also showed a positive effect on employability. In general, grades, as well as foreign language and IT-related certifications, are representative of important specs for employment. In addition, globalization and an IT-based business environment have made foreign language and IT related certifications more important for employment.

Total GPA was not found to affect employment in the group of low-ranked firms based on sales and net profit, or middle-ranked firms based on the average annual wage, compared with non-employment (

Table 4 and

Table 5). However, total GPA was highly correlated with employment and getting a job in the top 50 firms (Model 3 of

Table 5). GPA is a proxy variable for the ability to perform duties or obtain student achievements during college. However, several studies determined that when students with a high GPA had low interest in participating in additional career research activities, GPA had a reverse effect on employment [

37]. Cho

et al. [

38] also revealed that while GPA might be a parameter affecting employment, its influence is decreasing and GPA may instead have a negative effect. However, Jung and Lee [

39] reported that GPA was a very important factor for getting a job at large companies. Thus, since students with lower GPAs were employed based on their grades, it becomes a very important parameter to get jobs at large companies, or to gain good opportunities.

Students’ gender and major also significantly affect employment. Graduates with engineering majors get jobs in the top 50 and middle ranked firms, compared to students that major in business and economics, humanities and education, and science and bioengineering (

Table 4). Kim and Kim [

40] explained that engineering majors are more likely to have “good occupations” during the early career stages. In addition, most of the top 50 firms based on sales, net profits, and average annual wage are enterprises in the manufacturing sector, such as Samsung, Hyundai, LG,

etc., which naturally means that there is high demand for graduates with engineering majors. Especially, the probability of getting a job in the top 50 firms for graduates with information and communication engineering majors is higher than for those with engineering majors. The undergraduate program for information and communication engineering at Sungkyunkwan University covers broad areas of electronics, electrical and computer engineering which integrates information technology, nano-technology and bio-technology and places a great deal of emphasis on meeting requirements from the industry as exemplified by major companies such as Samsung Electronics.

When we look at the influence of the MR on employment according to the field of study, graduates in business and economics (see

Table A1), humanities and education, science and bioengineering, and engineering with a higher ratio of MR are less likely to be employed. These results show that conscientiousness in graduates reflected by dutifulness, responsibility, and sincerity, or agreeableness reflected by straightforwardness and altruism are important determinants of employment in most fields of study. Total GPA has a significantly positive effect on employment in the field of humanities and social sciences including business and economics, but has a negative effect in the field of natural sciences. This observation reflects the reality that graduates with science and engineering majors are highly in demand, even those with lower total GPA (The annual employment rate of graduates with engineering majors is more than 60%. Specifically, the employment rate of graduates majoring in humanities, social sciences, education, engineering, and natural sciences, are 48.4%, 54.4%, 49.0%, 67.5%, 52.2%, respectively [

41]).

Female students experienced a negative effect on employment and the probability of employment in top 50, middle ranked, and low ranked firms compared with male students. Some studies determined that the non-economically active population more than doubled for women compared to men, and women were also more likely to be employed in the relatively weak peripheral labor market in South Korea [

42,

43]. Thus, the empirical results in this study reflect the phenomenon explained by previous studies.

We also used the Tobit model, because sales, net profits, and average annual wages, which are dependent variables related to employment prestige, are usually zero if there are no data disclosed by companies. The Tobit estimates were also consistent with the results in

Table 4 and

Table 5 (see

Table A2).

6. Conclusions

This study analyzed the effects of graduates’ personalities, as indicated by monotonic responses (MR) to all the questions in a SET, on their employability by using Career-SET matched data for South Korean college graduates from 2008–2012. In this study, the response patterns in SET performed continually during the college years were examined to construct a variable for personality. The reasons for MR could be categorized according to a hypothesis of cost-benefit rationality from economics, with an aspect of increasing personal gains by selecting the same number for all questions in order to save time. MR may also be a negative factor in the labor market, as a reflection of insincerity, noncooperation, and impatience. The results of empirical analysis in this study suggest the latter case, the hypothesis that insincerity, noncooperation, impatience, etc. are more persuasive than the former.

The results from various estimation models, including Logit, Multinomial Logit, and Tobit, consistently indicated that those with a higher ratio of MR in SET are less likely to be employed or hired in lower prestige firms than the other comparison groups. More specifically, the results indicated that those who have a greater MR rate to all questions on the SET for every course are less likely to be employed than those who have a lower MR rate. In addition, the probability of gaining employment in the top 50, middle ranked or low ranked firms, as classified by yearly sales, net profits, and annual average wages, was lower. Other spec-related variables that influence employment, such as advanced IT and foreign language certification, and participation in programs abroad or student exchange, displayed positive influences on employability. In the case of total GPA, a positive impact on employment in the top 50 firms was observed.

Overall, we attempted to measure individual personality traits that are reflected by MR and explain them using the Big Five. The results indicate that graduates’ personalities, including deliberation, altruism, or impatience as well as their specs have significant effects on employability. This means that unlike the current practice in which firms rely simply on specs to hire employees, applicants’ invisible characteristics, such as personality, can also be screened by job interviewers. This suggests that the personnel management process still struggles to overcome the hurdle of insufficient information regarding students’ hidden and productive traits.

In this study, we demonstrated that MR has a negative correlation with employability using empirical results. This study provides useful information to identify students’ personality traits that are reflected by MR, and suggest that their attitude and personality are important factors in addition to specs in the labor market.