Abstract

The present study aims to make a contribution to the analysis of costs and benefits of adopting sustainable practices. The paper reports the results of an exploratory study into wineries’ perceived mix of economic costs and benefits and environmental benefits provided by participating in the Certified California Sustainable Winegrowing scheme. A total of 14 wineries, representing more than 50% of the entire wine production of California certified wine (and 25% of all certified wineries), participated in the study. Based on the information detected through face-to-face semi-structured interviews with winery managers and owners, performing a descriptive analysis and a logit model, we reveal that overall economic benefits, resulting from the sustainable practices introduced by the certification scheme, outweigh the additional costs. In particular, older wineries (>15 years) and those located in Sonoma Valley or onmultiple sites are more keen to assign a positive economic viability tosustainable practices. Furthermore, sustainable vineyard practices are highly rated by respondents in terms of both perceived environmental and economic benefits. Outcomes should foster similar studies exploring other specific sustainability programs and certification schemes, and eventually encourage cross-cultural investigations.

1. Introduction

Sustainability is generally referred to as the triple bottom line as it involves the integration of environmental and social responsibilities with economic goals to create value for a company as well as for society [1]. The winegrowing sector has a long history of commitment to promoting a more sustainable development and several initiatives are underway worldwide. First, it is worth making a reference to the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV) definition, as an international framework. Sustainable vitiviniculture is a “global strategy on the scale of the grape production and processing systems, incorporating at the same time the economic sustainability of structures and territories, producing quality products, considering requirements of precision in sustainable viticulture, risks to the environment, products safety and consumer health and valuing of heritage, historical, cultural, ecological and landscape aspects” [2]. The key idea is that the above-mentioned triple bottom line should be promoted through the implementation of appropriate environmental sustainability programs, and applied to production, transformation, warehousing, and packaging.

A number of ways of implementing sustainability in the wine industry have been developed and used during the past 20 years, based on voluntary environmental and social standards andcertifications. Furthermore, many different sustainable winegrowing programs, developed through collaborative efforts driven by national institutions and associations, arecurrently underway in so-called New World wine-producing countries (Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, USA, and recently Chile). Whereas the initiatives carried out in the core European producing countries, on the other hand, primarily concern single winegrowing areas or limited groups of winegrowers [3,4].

Two recent literature reviews [5,6] have highlighted that several authors have analyzed the drivers that could explain voluntary adoption of sustainable practices, focusing on the cost and the benefits perceived by producers.

Nowadays, there seems to be a broad consensus that internal drivers play a much larger role than external motivations. Indeed, managerial attitudes, concern about environmental impacts and employee safety, company culture, protection of land, and social responsibility appear to be the key drivers for sustainability [7,8,9]. Among the many external drivers, the most cited by researchers are: compliance with regulations, especially pre-emption of future regulations, core requirements for export (especially in the more export-oriented countries, such as New Zealand and South Africa), and pressure from large retailers.

While taking into account the evaluation of the benefits and costs of embracing sustainable practices, the empirical evidence is quite conflicting. Ideally, sustainable practices provide environmental and social benefits, and should at the same time reduce input costs and increase economic returns to producers. However, previous research from the wine industry reports mixed results in terms of the costs and benefits relating to the adoption of sustainable practices (e.g., [10]). Some research has highlighted, among the main benefits, an enhanced reputation, image, and working environment [11,12,13], improved product quality [8], lower legal and regulatory risks, and greater operational efficiency. In addition, for wineries that have implemented a formal environmental management system, cost benefits deriving from supply chain optimization [14] have also been identified. Overall, economic and marketing benefits, in terms of price and loyalty, are actually constrained mainly by low consumer knowledge about sustainable wine and its logos [13,15,16]. Nevertheless, some recent research reports increasing consumer interest in environmentally friendly or socially responsible wines [17,18,19,20,21,22].

Moreover, other potential barriers to the adoption of sustainable practices have been identified, namely high costs and an administrative burden related to the certification process and the lack of knowledge/information/skills [23,24]. In particular, while there are some sustainable practices for which winegrowers have enough information and clearly state that the economic benefits exceed the costs, for others they perceive a high level of uncertainty about their effectiveness and benefits. Thus, to promote a greater spread of sustainable practices among winemakers, it is a priority to bridge the still substantial knowledge gaps in terms of perceived environmental benefits, economic benefits, and costs.

While there is a growing body of research examining the profitability of wine businesses engaging in sustainable development, to the best of our knowledge, no study has specifically focused on the members of a specific certification program.

In this context, the present study aims to make a contribution to the analysis of costs and benefits of adopting sustainable practices. In particular, the paper explores wineries’ perceived mix of economic costs and benefits and environmental benefits derived from participating in the Certified California Sustainable Winegrowing (CCSW) scheme. This group of firms has been chosen because the CCSW scheme is recognized worldwide as being the pioneer in wine sustainability and the focus on education and training of producers as part of their continuous improvement is a main strength of this program [25].

2. Certified California Sustainable Winegrowing Scheme

California’s wine industry (the wineries of which account, on average, for 90% of the total US wine production and acreage) has made extensive progress since the Wine Institute’s initial work on its sustainability code back in 2002. This progress fostered, in 2003, the establishment of the California Sustainable Winegrowing Alliance (CSWA—a non-profit organization), a collaboration between the Wine Institute and the California Association of Winegrape Growers (CAWG). The Sustainable Winegrowing Program is designed to stimulate a “cycle of continuous improvement” among growers and vintners by enabling them to evaluate their operations, learn about new approaches and innovations, develop action plans for improvements, and implement changes to increase their adoption of sustainable practices. The CSWA, drawing on previous experiences, based on voluntary initiatives by firms, local communities, and by national trade associations, such as the Lodi Winegrape Commission, the Central Coast Vineyard Team, and the Napa Valley Grape Growers Association [25], introduced Certified California Sustainable Winegrowingin 2010. Certified California Sustainable Winegrowing is a voluntary, third-party certification program for California vineyards and wineries that is based on the California Code of Sustainable Winegrowing Workbook. In brief, the main requirements for the certification are: (1) an annual self-assessment on the 138 vineyard and 103 winery best practices using the California Code of Sustainable Winegrowing Workbook (during a regularly scheduled third-party audit); (2) embracing all prerequisite criteria (50 vineyard prerequisites and 32 winery prerequisites) by scoring 2 or higher for each specific criteria; (3) demonstration of a process for identifying the key sustainability issues for the company, prioritizing areas for improvement, and establishing action plans that are implemented and updated every year; (4) the ability to demonstrate practices that maintain or improve Sustainable Winegrowing Program (SWP) criteria and methods to correct any items identified internally or by an auditor as inconsistent with SWP self-assessment categories; (5) demonstration ofcontinuous improvement over time.

Currently, the total acres of CCSW-certified vineyards represent around 12% of the entire California wine acreage, and 212 million wine cases are produced by CCSW-certified wineries (around 50% of all the cases produced in California).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Constructs and Sources

Given the limited secondary data available to satisfy the research objectives, primary data collection was required. Data were collected on the opinions, views, and perceptions of wineries (and, where available, supporting secondary data) regarding the costs and benefits of their current sustainability practices and programs implemented to achieve the certification standards. After conducting a systematic review of the relevant literature, and a discussion with managers of the CSWA and the Wine Institute (who can be considered key informants), the main findings were used as the basis for face-to-face semi-structured interviews with certified winery representatives. Direct interviews were preferred to a questionnaire to allow the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data and to permit the researcher to personally observe the sustainability efforts of interviewees. Final items were drawn and adapted from Lubell and colleagues [23] for sustainable vineyard practices, and from Marshall et al. [7,10] and Szolnoki [26] for general sustainability information. Together with key informants, a common understanding was found on how sustainability practices impact the cost structure and value of the supply and, consequently, how costs and benefits can occur. Consensus was established around the idea that fixed costs usually increase (as technical investments, information acquisition, new procedure implementation and monitoring systems) while variable costs are expected to decrease, and that potential competitive advantages (in terms of product pricing) may occur. Such a pattern was therefore proposed to interviewees when they were requested to provide an overall costs/benefits assessment of the adoption of sustainable practices. Moreover, together with key informants and on the basisof relevant literature, the complex set of critical activities for sustainability was classified in 11 core categories of sustainable practices. For the vineyards the eight final categories were: pest management, disease management, weed management, water management, soil management, vine management, alternative energy, and business management. For the wineries the three categories were: recycling practices, reducing practices and planning, and monitoring goals and results.

3.2. Questionnaire Structure

The questionnaire was pretested with the advice of agribusiness professionals and local academics in June 2013. Several adjustments were made to some questions to increase clarity and understanding. The final questionnaire used for face-to-face semi-structured interviews was composed by 35 questions (open-ended and close-ended), grouped in four sections. The first section, named winery descriptive information, included 6 questions collecting data on annual production, turnover, export, the price range of wines, and the age of winery. The second group of questions analyzed general sustainability information (adapted from Szolnoki [26] and Marshall et al. [7,10]); specifically, 5 questions regarding sustainability views of interviewee, sustainability-related data collection and processing, and motivations to participate in the CCSW were gathered. These questions were all open-ended to allow participants to freely express themselves, exceptfor one that adopted a Likert scale (agreement ranging from 1 to 7, with endpoints 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree). The third section included 15 questions, defined as sustainability practices impact, which investigated the interviewee’s perception of specific sustainability practices in terms of costs and benefits (adapted from Lubell et al. [23]). To achieve reliable information, these questions were all close-ended and the order was randomized. For each practice, the interviewee was asked to rate the related economic benefits, economic costs, and environmental benefits on a scale from 1 to 9 (from low to high). Reversed items were also used to minimize the potential for response bias. The general assessment of economic benefits versus economic costs of sustainability practices in the vineyard, in the winery, and overall was collected with dichotomous questions (i.e., overall economic benefits of sustainability practices introduced in the vineyard overweigh economic costs?). The fourth section of the questionnaire, on CCSW certification overall perception, included nine items in which participants were asked to rate overall effects of CCSW certification on wine quality and vineyard health (the scale ranged from −3 = very negative to +3 = very positive, with 0 = no effect). The “Do not know” responses were common and were recorded as missing values rather than as singular scores as they did not follow the logical sequence of the responses. For a complete overview of the questionnaire-building process and rationale, please see Vecchio [27].

3.3. Sample

Fromthe wineries participating in the CCSW scheme, 54 in all were invited to participate in the survey. After initial contact by mail and phone, appointments were made with wineries that agreed to participate. Over an approximate two-month period (July–August 2013) one of the authors conducted a total of 14interviews with key managers or owners. A total of 14 wineries, representing more than 50% of the entire wine production of California certified wine (and 25% of all certified wineries), participated in the study. Care was taken to ensure a representative variety of certified Californian wineries across the main wine-producing areas, including different firm sizes, ages, and (main) price categoriesof wines sold. Indeed, the interviewees represented wineries that were diverse in terms of size, location, and market segment served. It is also important to point out that, before investigating wineries’ perceived benefits and costs, we asked all respondents whether reliable quantitative data were currently available on the economic performance of all implemented sustainable practices. None of the interviewees had precise information (or an ongoing information-gathering process) on the topic.

3.4. Data Processing

After performing a descriptive analysis, a multivariate technique was applied to investigate the differences in individual winery perception of the overall assessment of total economic costs and benefits. In particular, a logit model was performed, in which the explanatory variable vector is made up of a group of dichotomous variables associated with the individual characteristics of the winery, while the dependent variable is binary (i.e., y takes the value one when the overall assessment of the costs/benefits ratio of sustainability is positive and zero if otherwise; in addition, it is assumed that the error is independent of the independent variables and that it follows a standard logistic distribution). An ordered specification, taking into account uncertain respondents, was not selected, as it seemed excessively rigid. The multinomial model specification was also tested as an appropriate model; however, the obtained results in the estimate suggest that the model was not efficient. The results of the evaluation of the goodness-of-fit statistics of the logit and probit models suggested that the logit model had a greater degree of efficiency.

4. Results

The annual number of wine bottles produced in the respondents’ wineries ranged from less than 5000 to more than one million cases. Fifty percent of the wineries produce between 25,001 and onemillion cases, 22% between 5000 and 10,000, and 14% over one million. Six wineries were established over 25 years ago, four were between 10 and 24 years old, andtwo started operating less than 10years ago. The interviewees were primarily owners, members of the executive management or of other prominent levels of management. Considering location, about 36% of the firms are located in Sonoma Valley, another 36% only in Napa Valley, and the remaining 28% are located in multiple areas. The profiles of the responding wineries are summarized in Table 1, complete with location, interviewee’s position, winery size, and the main wine price category sold.

Table 1.

Descriptive information of sampled wineries.

| Winery Code | Location | Interviewee | Size (Average Number of Cases Produced Annually) | Predominant Category of Wine Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SON 1 | Only Sonoma Valley | Executive manager | 25,001–1 million | Super premium |

| SON 2 | Only Sonoma Valley | Owner | <5000 | Luxury |

| SON 3 | Only Sonoma Valley | Owner | 5001–10,000 | Ultra premium |

| SON 4 | Only Sonoma Valley | Owner | 5001–10,000 | Ultra premium |

| SON 5 | Only Sonoma Valley | Executive manager | 25,001–1 million | Super premium |

| MUL 1 | Napa, Sonoma Valley and other California | Sustainable manager | >1 million | Popular premium |

| MUL 2 | Napa, Sonoma Valley and other California | Executive manager | 25,001–1 million | Super premium |

| MUL 3 | Napa, Sonoma Valley and other California | Executive manager | 25,001–1 million | Super premium |

| MUL 4 | Napa, Sonoma Valley and other California | Sustainable manager | >1 million | Super premium |

| NAP 1 | Only Napa Valley | Executive manager | 25,001–1 million | Popular premium |

| NAP 2 | Only Napa Valley | Owner | 5001–10,000 | Luxury |

| NAP 3 | Only Napa Valley | Executive manager | 25,001–1 million | Ultra premium |

| NAP 4 | Only Napa Valley | Owner | 10,001–25,000 | Ultra premium |

| NAP 5 | Only Napa Valley | Sustainable manager | 25,001–1 million | Ultra premium |

Note: category of wine prices per 0.75 liter bottle are respectively: Popular premium ($3–7), Super premium ($8–14), Ultra premium ($15–25), and Luxury (over $26).

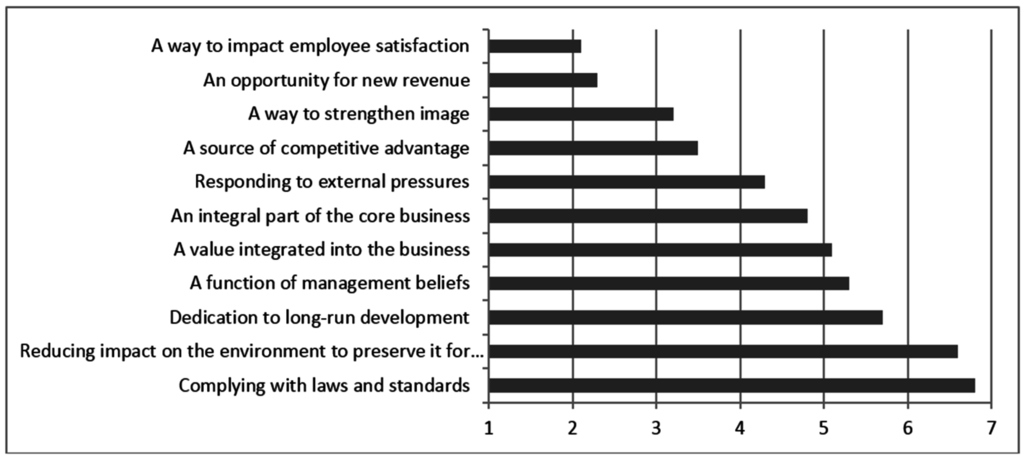

To better comprehend interviewees’ general attitude towards sustainable development issues, a preliminary question elicited sustainability views, i.e., the main reasons to achieve superior sustainable performances. Figure 1 shows respondents’ mean scores for all analyzed constructs. Complying with laws and standards ranks first, with a mean score of 6.8, followed by reducing impact on the environment to preserve it for the future, and dedication to long-run development, with a mean score, respectively, of 6.6 and 5.7. Less importance is assigned to sustainability as a way to affect employee satisfaction, with an average score of 2.1; sustainability as an opportunity for new revenues received an average score of 2.3. A further point to highlight is that respondents do not see sustainability as a way to strengthen image, or as a source of competitive advantage.

Figure 1.

Mean scores of respondents’ sustainability views. Note: Rating scale is 1–7 (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree).

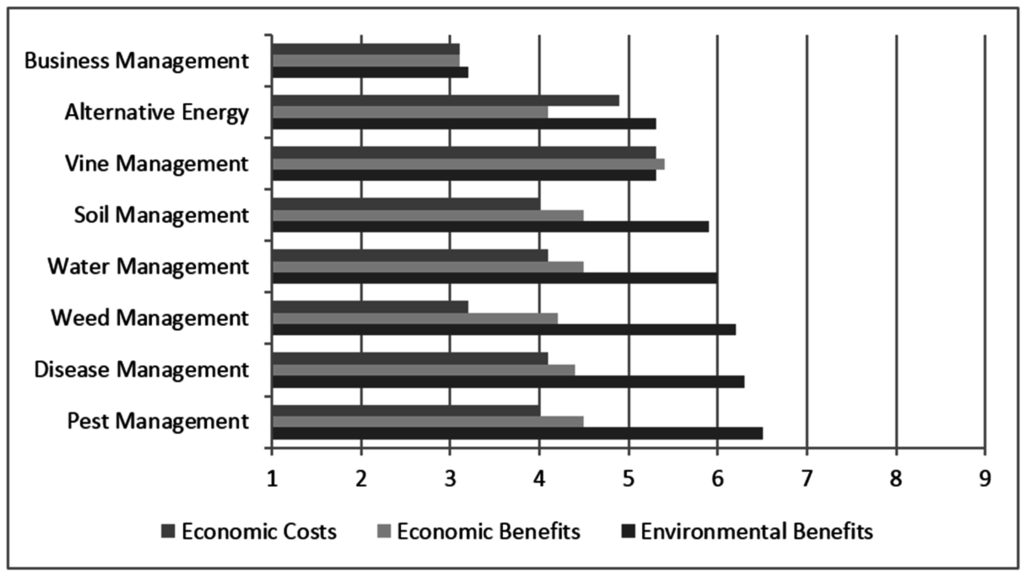

As depicted in Figure 2, sustainable viticulture practices vary in their perceived benefits and costs.

Figure 2.

Mean scores of economic benefits, economic costs, and environmental benefits of selected sustainable vineyard practices. Note: Scale is 1–9 (1 = very low; 9 = very high).

If we consider only the perceived costs, the practices that are perceived to be more costly are alternative energy and vine management.

However, the economic benefits are viewed as exceeding the costs for the majority of practices considered, with the notable exception of alternative energy and vine management. Incontrast, for business management, economic costs and benefits were almost equal. Environmental benefits were strongly connected to pest management, disease management, weed management, and water management.

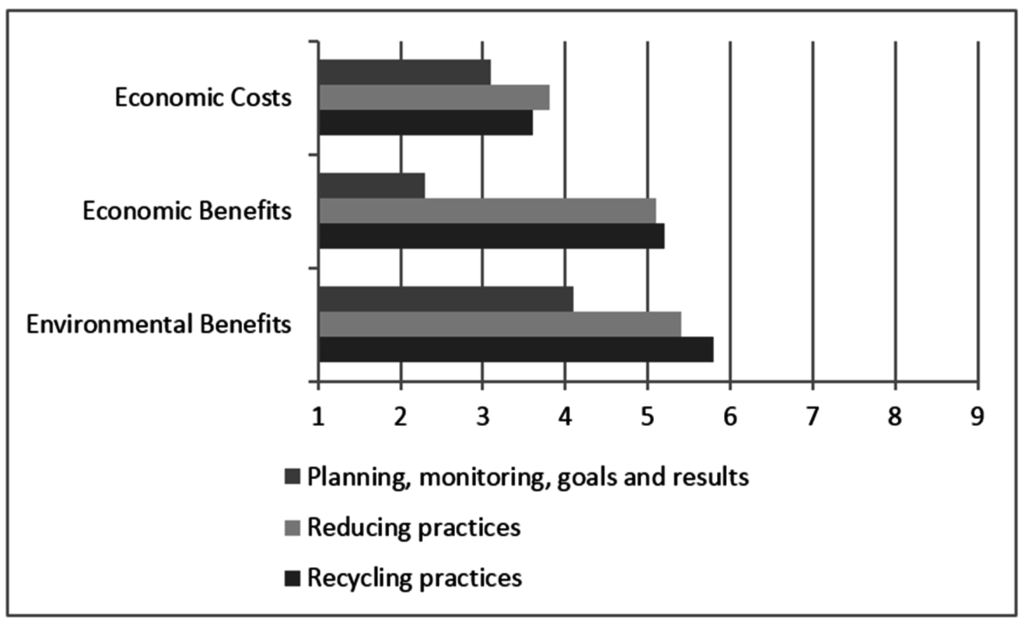

Similarly, in order to evaluate respondents’ perceptions of sustainable winery practices, we asked them to rate the environmental benefits, economic costs, and benefits of the three previously identified macro-categories (i.e., recycling practices, reducing practices—which include reducing toxic chemicals, reducing water use, reducing energy use, and reducing solid waste—and planning, monitoring goals, and results). Figure 3 represents the mean scores obtained. Planning and monitoring goals and results (in the winery) is perceived by respondents as the only practice in which economic costs outweigh the economic benefits. Furthermore, it is considered in absolute terms as the practice fostering fewer environmental benefits.

Figure 3.

Mean scores of economic benefits, economic costs, and environmental benefits of selected winery sustainable practices. Note: Scale is 1–9 (1 = very low; 9 = very high).

Recycling practices (such as recycling pomace and lees, glass, pallets, etc.) are considered among the three most effective in terms of positive environmental impacts, and they are perceived as practices with higher economic benefits compensating economic costs.

Likewise, participants assign a similar delta in terms of the difference between economic benefits and economic coststo reducing practices.

To arrive at a general picture of respondents’ perceived economic impact of the practices implemented to obtain the Certified California Sustainable Winegrowing scheme, a question on overall assessment of total economic costs and benefits was formulated.

Eight interviewees (67% of the sample) considered overall benefits higher than costs; four respondents perceived the opposite; and two were unable to value total costs and benefits precisely.

Table 2 shows the logit regression results, estimated via the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method.

The sign of Location is negative and significant at the 5% level. This finding suggests that the wineries located in Napa Valley are less convinced of the economic advantage of participating in the sustainable wine program. Conversely, the sign ofage of winery is positive and significant at the 10% level, suggesting that older wineries have a better perception of the economic viability of sustainability. Other variables considered in the model are not statistically significant. Nevertheless, signs suggest that larger wineries and those more oriented towards lower-priced wines are more keen to consider the benefits of sustainability practices as higher than theircosts.

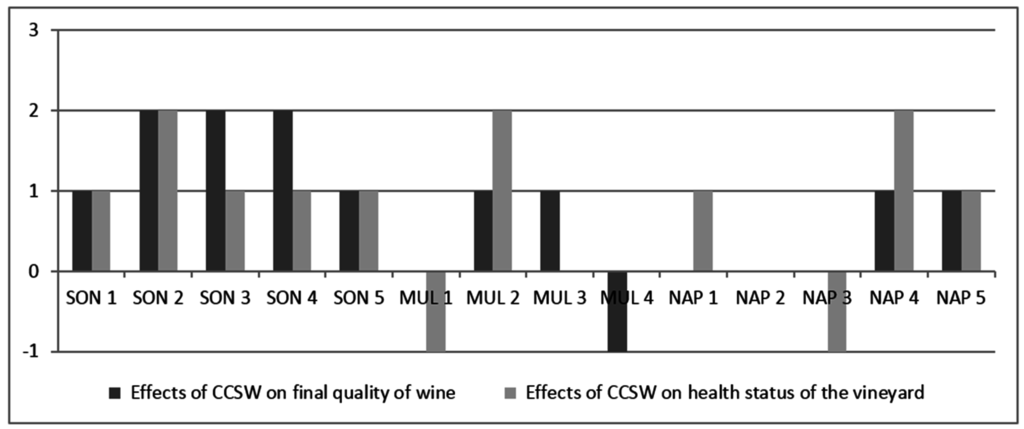

Finally, we investigated wineries’ overall perceptions of the effects of the certification scheme practices on general wine quality and vineyard health. Sample means are, respectively, 0.75 (SD 0.96) and 0.67 (SD 1.07). Figure 4 clearly shows that wineries strongly differ in their evaluations of the sign of overall impacts, as all the companies located in Sonoma Valley positively rate the effects of certification practices on wine quality and vineyard health, while firms in Napa Valley and in several areas of California expressed contrasting values.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates of the logit model.

| Regressors | |

|---|---|

| Constant | 1.878 (1.25) |

| Location | −3.412 ** |

| (1 = Located in Napa Valley, 0 = otherwise) | (−2.209) |

| Interviewee | |

| (1 = Owner, 0 = otherwise) | |

| 1.131 (1.106) | |

| Size | 2.034 |

| (1 = Average number of cases produced annually over 25,000, 0 = otherwise) | (1.992) |

| Predominant category of wine price | 2.328 |

| (1 = Popular and Super premium, 0 = otherwise) | (2.195) |

| Share of export | 1.789 |

| (1 = Over 15%, 0 = otherwise) | (1.653) |

| Age of winey | 2.803 * |

| (1 = Over 15 years, 0 = otherwise) | (2.206) |

Note: The dependent variable is the binary variable of overall sustainability benefits exceeding costs (yes/no). * Significant at the 10% level, ** significant at the 5% level, *** significant at the 1% level.

Figure 4.

Wineries’ ratings of overall effects of CCSW certification on wine quality and vineyard health. Note: Scale is −3 (very negative) to +3 (very positive). 0 = no effect.

5. Concluding Discussion

Sustainability is a core goal for policy-makers and private companies; however, environmental and social benefits of different sustainable practices should always be balanced against overall profitability, and this of course holds in the wine production sector as well. Nowadays, there is a growing body of academic and professional literature on sustainability in the wine sector; moreover, several of these papers are focused on California in particular. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, none of these has specifically focused on empirical evidence from participants of the Certified California Sustainable Winegrowing program, or other officially recognized protocols for sustainable production. The case of the CCSW scheme is particularly interesting as an important group of wineries—both in terms of production volumes and marketing power—have voluntarily decided to adopt a sustainability pathway embracing necessary innovations and managerial changes. Exploring these wineries’ perceptions of overall and specific environmental benefits, economic costs, and economic benefits of sustainable vineyard and winery practices provides useful data for stakeholders and policy-makers interested in enhancing the overall sustainability of the wine industry.

Findings of current research prove that the majority of respondents perceive that the overall economic benefits, resulting from the sustainable practices introduced by the certification scheme, outweigh the costs. Specifically, almost all investigated vineyard and winery practices received quite high scores in terms of both perceived overall environmental benefits and economic benefits. However, respondents evaluated only three practices as more cost-generating (two vineyard practices, vine management and alternative energy management, and one winery practice, planning and monitoring sustainability goals and results). Moreover, most of the wineries recognize beneficial effects for wine quality and vineyard health. It should be highlighted that positive results are obtained in very different situations in terms of winery size, location, and production orientation. The categories of practices with a negative balance between benefits and costs deserve some additional comments. Concerning alternative energy to sustain vineyard operations, the low cost of energy from fossil sources in the US makes such sources competitive compared to farm self-produced energy. Interesting is the case of costs and benefits originating from the planning of resource use and monitoring of results compared to specific performance parameters. As already noted, such activities are key aspects of the sustainable production paradigm and are considered useful to reach important goals in the short and medium run. Nevertheless, interviewees appear unable to perceive such benefits and do not recognize a direct connection between good results related to single aspects of production and planning/monitoring activities. A possible interpretation of such a contradiction can be found in the motivation pushing Californian wineries to massively adhere to CCSW, which is the desire to comply with law and standard. Indeed, the political and social environment of California is very pressing toward sustainability, mostly fostering environmental care, determining a decisive stimulus to join the sustainability scheme even without a profound acquisition of principles of sustainable production. Nevertheless, an incomplete awareness of technical and economic aspects of the continuous process of enhancement of sustainability was quite evident during interviews, and it is possible to conclude that a better understanding of specific sustainable practices—which still have uncertain economic costs (or benefits) but clearly produce major environmental or social benefits—may improve the overall satisfaction of adopting sustainable practices. Finally, the discreet selection model (logit) identified that a firm’s individual characteristics have a limited influence on the probability of perceiving the benefits of sustainability as higher than the costs, highlighting that older wineries (>15 years) and those located in Sonoma Valley or in multiple sites are more keen to assign a positive economic viability of sustainable practices. This could probably be explained by the fact that older wineries might be more equipped, and experienced, to effectively handle the fine-tuning of production techniques required by sustainability improvements compared to their younger counterparts. On the other hand, it might be due to the fact that itmay take time to achieve economic benefits gained from sustainability practices. In addition, the geographical positioning of wineries’ impact on the cost/benefit evaluation of sustainability could be related to possible differences in the local organization of the entire supply chain or to climatic conditions which could relevantly increase the ease of managing sustainable practices (i.e., less susceptible to fungal diseases).

Analyzing the current literature, there is no clear picture of the economic advantage of sustainable wine production [28,29,30]. Our findings confirm previous results [24] that reveal an improvement of overall wine quality and vineyard health, which are benefits that can easily be seen as economically beneficial in the long term. Indeed, as suggested elsewhere [23], research should focus on some of the practices where there are still substantial knowledge gaps in terms of overall environmental benefits and economic benefits/costs. This is because such knowledge gaps pose a substantial barrier to adopting practices and, in general, there is a loss aversion effect that induces people to inflate cost expectations and discount benefits.

Our study has several limitations. First, as the topic is extremely complex and wide-ranging, several simplifications were made to generate a general portrayal of the current state-of-the-art. Secondly, our research had an exploratory nature, while in-depth quantitative analyses of wineries’sustainability practices (counting for specific business characteristics) would provide further insights on the exact rationale of a positive or negative overall evaluation of the costs/benefit ratio. In addition, no specific care was taken to control for the differences between the views of the individual respondent completing the survey and the views of the company that he or she represented, whereas individual interpretations are known to influence how a company is portrayed. Nevertheless, the current research should encourage similar studies to isolate and compare specific viticulture regions in order to identify the unique place-based factors influencing overall benefits and costs, and provide key insights into the impact of regional/national sustainable viticulture programs. Indeed, data collection could be extended to wineries in other countries as a way to compare sustainability practices on a global scale, even if, as Szolnoki [26] effectively points out, it is still very difficult to define the term “sustainability” because not only every country but also every entrepreneur has a different understanding of sustainability in the wine industry. Inregards to the focus of future research, attempts could be made to identify the stages of the production process or environmental conditions which are highly critical in terms of economic costs. New research avenues could also compare costs and benefits of sustainable practices in the wine industry with other important agricultural sectors. Finally, further research should carefully analyze the interesting possibilities offered by linking wineries’ (in California and elsewhere) management systems, environmental declarations, life cycle assessments and similar aspects using a product-oriented environmental management system (POEMS), as the POEMS offers an approach to address both policy sustainability goals and growing consumer interest in sustainable productions [31,32,33].

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge a grant from the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV) assigned to Riccardo Vecchio, entitled “Economic impact of Sustainable Viti-viniculture best practices”.

Author Contributions

Current research was designed together by the three authors, data gathering was performed by Riccardo Vecchio. Data analysis was performed jointly by all authors. All authors wrote, read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Elkington, J. Enter the Triple Bottom Line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does it All Add Up? Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV). Resolution CST 1/2008. OIV Guidelines for Sustainable Vitiviniculture: Production, Processing and Packaging of Products. Available online: http://www.oiv.int/oiv/cms/index (accessed on 1 October 2012).

- Klohr, B.; Fleuchaus, R.; Theuvsen, L. Sustainability: Implementation programs and communication in the leading wine producing countries. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research (AWBR), St. Catharines, ON, Canada, 12–15 June 2013.

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R.; Verneau, F. A future of sustainable wine? A reasoned review and discussion of ongoing programs around the world. Calitatea 2014, 15 (S1), 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casini, L. Sustainability in the wine industry: Key questions and research trends. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, A.; Vastola, A. Sustainable winegrowing: Current perspectives. Int. J. Wine Res. 2015, 7, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.S.; Cordano, M.; Silverman, M. Exploring individual and institutional drivers of proactive environmentalism in the US wine industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabzdylova, B.; Raffensperger, J.F.; Castka, P. Sustainability in the New Zealand wine industry: Drivers, stakeholders and practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghoef, N.; Dodds, R. Determinants of interest in Eco-labeling in the Ontario wine industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.S.; Akoorie, M.E.M.; Hamann, R.; Sinha, K. Environmental practices in the wine industry: An empirical application of the theory of reasoned action and stakeholder theory in the United States and New Zealand. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullman, M.E.; Maloni, M.J.; Dillard, J. Sustainability practices in food supply chains: How is wine different? J. Wine Res. 2010, 21, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Graci, S.; Ko, S.; Walker, L. What drives environmental sustainability in the New Zealand wine industry? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2013, 25, 64–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Grant, L.E. Eco-labeling strategies and price-premium: The wine industry puzzle. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 6–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, T.; Gilinsky, A., Jr.; Newton, S.K. Environmental strategy: Does it lead to competitive advantage in the US wine industry? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2012, 24, 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, N.; Taylor, C.; Strick, S. Wine consumers’ environmental knowledge and attitudes: Influence on willingness to purchase. Int. J. Wine Res. 2009, 1, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginon, E.; Ares, G.; Laboissière, L.H.E.D.S.; Brouard, J.; Issanchou, S.; Deliza, R. Logos indicating environmental sustainability in wine production: An exploratory study on how do Burgundy wine consumers perceive them. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghoef, N.; Dodds, R. Potential for sustainability eco-labeling in Ontario’s wine industry. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2011, 23, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klohr, B.; Fleuchaus, R.; Theuvsen, L. Who is buying sustainable wine? A lifestyle segmentation of German wine consumers. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research, Geisenheim, Germany, 28–30 June 2014.

- Lopes, P.; Sagala, R.; Dood, T. Extrinsic wine attributes importance on Canadian consumers purchase decisions for environmentally sustainable wines. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research, Geisenheim, Germany, 28–30 June 2014.

- Mueller, S.; Remaud, H. Impact of corporate social responsibility claims on consumer food choice: A cross-cultural comparison. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 142–166. [Google Scholar]

- Pomarici, E.; Vecchio, R. Millennial generation attitudes to sustainable wine: An exploratory study on Italian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R. Determinants of willingness-to-pay for sustainable wine: Evidence from experimental auctions. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M.; Hillis, V.; Hoffman, M. Innovation, cooperation, and the perceived benefits and costs of sustainable agriculture practices. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16. Article 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M.; Hillis, V.; Hoffman, M. The Perceived Benefits and Costs of Sustainability Practices in California Viticulture; Research Brief; Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior: Davis, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cordano, M.; Marshall, R.S.; Silverman, M. How do Small and Medium Enterprises Go “Green”? A Study of Environmental Management Programs in the U.S. Wine Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G. A cross-national comparison of sustainability in the wine industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R. Vitiviniculture best practices. Bull.I'OIV 2014, 87, 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, S.L.; Cullen, R.; Grout, R. Adoption of environmental innovations: Analysis from the Waipara wine industry. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L.; de Silva, T.A. Analysis of environmental management systems in New Zealand wineries. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2012, 24, 98–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tee, E.; Boland, A.M.; Medhurst, A. Voluntary adoption of Environmental Management Systems in the Australian wine and grape industry depends on understanding stakeholder objectives and drivers. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2007, 47, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, P.; Ioppolo, G. From Theory to Practice: Enhancing the Potential Policy Impact of Industrial Ecology. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2259–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattara, C.; Raggi, A.; Cichelli, A. Life cycle assessment and carbon footprint in the wine supply-chain. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Point, E.; Tyedmers, P.; Naugler, C. Life cycle environmental impacts of wine production and consumption in Nova Scotia, Canada. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 27, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).