A Referential Methodology for Education on Sustainable Tourism Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Education for Sustainable Tourism Development

- (1)

- Social responsibility is the perceived level of interdependence of and social concern for others, society and the environment. The sub-dimensions of social responsibility are listed as global justice and disparities, altruism and empathy and global interconnectedness and personal responsibility.

- (2)

- Global competence is having an open mind while actively seeking to understand others’ cultural norms and expectations and leveraging this knowledge to interact, communicate and work effectively outside one’s environment. The sub-dimensions of global competence are self-awareness, intercultural communication and global knowledge.

- (3)

- Global civic engagement is the demonstration of action and/or the predisposition toward recognizing local, state, national and global community issues and responding through actions, such as volunteerism, political activism and community participation. The sub-dimensions of global civic engagement are involvement in civic organizations’ political voice and glocal civic activism.

3. Background Information of the Educational Program

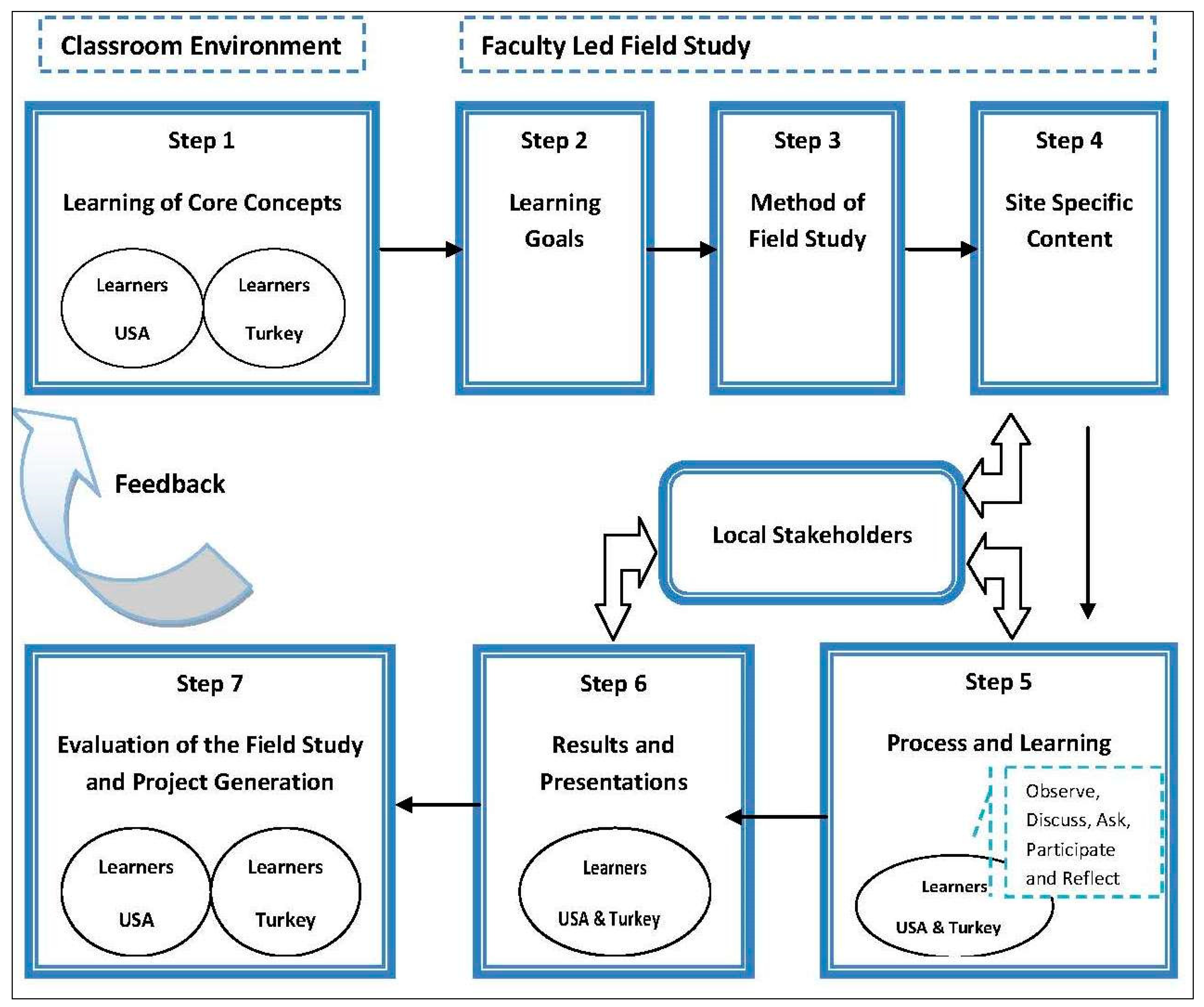

4. Design of the Educational Program

- (1)

- Define sustainable tourism,

- (2)

- Attain cross-cultural understanding and engage in bi-national collaborations,

- (3)

- Discuss and recommend how sustainable rural tourism development can aid the improvement of QoL at a destination.

- ecological vitality: quality of local and global environment with access to nature

- governance: confidence in each level of government and freedom from discrimination

- material wellbeing: satisfaction with financial situation and financial future

- psychological wellbeing: issues of self-esteem, autonomy and sense of purpose

- physical health: physical health and experience of disability or long-term illness.

- time and work-life balance: senses of stress, control over their lives and overwork

- social vitality and connection: interpersonal trust, social support and community participation

- education: participation in educational activities, discrimination

- cultural vitality: participation in arts and culture, sport and recreation activities

- Meet with Tasköprü Chamber of Agriculture and take part in the garlic harvest

- Lunch at a village house with the community

- A visit to the Municipality

- A visit to the archeological site at Pompeipolis, meeting with the archeologists and the site coordinator

- A visit to the Tasköprü Festival area (a local festival held after the garlic harvest)

- Dinner with the excavation team

- Observe local community traditions, food preparation, economic activities, religious practices and arts and folkloric dances

- Ask questions of stakeholders and community members

- Participate in a local festival and community service

- Discuss issues with group members

- Reflect alone

- (1)

- A brief overview of what each indicator means and how it connects to sustainability in the Kastamonu community.

- (2)

- To describe ways in which residents can achieve sustainability through tourism development in the Kastamonu community.

- (3)

- To list interesting sustainability-related facts in the Kastamonu community.

5. Evaluation of the Educational Program

6. Findings and Discussion

| All Students | Turkish Students | American Students | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paired Difference Mean | t-score | Significance (2-tailed) | Paired Difference Mean | t-score | Significance (2-tailed) | Paired Difference Mean | t-score | Significance (2-tailed) | |

| Social Responsibility: Global Justice and Disparities | |||||||||

| It is OK if some people in the world have more opportunities than others. | 0.250 | 1.760 | 0.090 | 0.385 | 1.806 | 0.096 | 0.133 | 0.695 | 0.499 |

| Global Competence: Intercultural Communication | |||||||||

| I often adapt my communication style to other people’s cultural background. | –0.393 | –2.645 | 0.013 | –0.462 | –1.585 | 0.139 | –0.333 | –2.646 | 0.019 |

| I am able to communicate in different ways with people from different cultures. | –0.357 | –2.423 | 0.022 | –0.154 | –1.477 | 0.165 | –0.667 | –2.870 | 0.012 |

| Global Competence: Global Knowledge | |||||||||

| I am informed of current issues that impact international relationships. | –0.222 | –2.280 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | –0.429 | –3.122 | 0.008 |

| I feel comfortable expressing my views regarding a pressing global problem in front of a group of people. | –0.593 | –3.309 | 0.003 | –0.615 | –2.309 | 0.040 | –0.571 | –2.280 | 0.040 |

| Global Civic Engagement: Involvement in Civic Organizations | |||||||||

| Over the next six months, I plan to do volunteer work to help individuals and communities abroad. | –0.357 | –2.173 | 0.039 | –0.462 | –2.144 | 0.053 | –0.267 | –1.075 | 0.301 |

| Global Civic Engagement: Political Voice | |||||||||

| Over the next six months, I will contact a newspaper or radio to express my concerns about global environmental, social or political problems. | –0.357 | –1.987 | 0.057 | –0.462 | –2.144 | 0.053 | –0.267 | –.939 | 0.364 |

| Over the next six months, I will display and/or wear badges/stickers/signs that promote a more just and equitable world. | –0.429 | –2.714 | 0.011 | –0.231 | –1.148 | 0.273 | –0.600 | –2.553 | 0.023 |

| Over the next six months, I will express my views about international politics on a website, blog or chat room. | –0.250 | –1.491 | 0.148 | –0.385 | –2.739 | 0.018 | –0.133 | –0.459 | 0.653 |

| Over the next six months, I will sign an e-mail or written petition seeking to help individuals or communities abroad. | –0.071 | –0.386 | 0.702 | –0.385 | –2.132 | 0.054 | 0.200 | 0.676 | 0.510 |

7. Conclusions

Appendix

| Statements | Mean | Standard Deviation | Paired Difference Mean | t-score | Significance (2-tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I think that most people around the world get what they are entitled to have. | pre- | 1.86 | 0.891 | 0.107 | 0.682 | 0.501 |

| post- | 1.75 | 0.887 | ||||

| It is OK if some people in the world have more opportunities than others | pre- | 2.25 | 0.752 | 0.250 | 1.760 | 0.090 * |

| post- | 2.00 | 0.943 | ||||

| I think that people around the world get the rewards and punishments they deserve. | pre- | 1.81 | 0.681 | −0.037 | −0.214 | 0.832 |

| post- | 1.85 | 0.770 | ||||

| In times of scarcity. it is sometimes necessary to use force against others to get what you need. | pre- | 1.86 | 0.970 | 0.214 | 1.362 | 0.184 |

| post- | 1.64 | 0.951 | ||||

| The world is generally a fair place. | pre- | 1.89 | 0.567 | 0.071 | 0.570 | 0.573 |

| post- | 1.82 | 0.548 | ||||

| No one country or group of people should dominate and exploit others in the world. | pre- | 4.25 | 1.143 | −0.036 | −0.126 | 0.901 |

| post- | 4.29 | 1.013 | ||||

| The needs of the worlds’ most fragile people are more pressing than my own. | pre- | 3.59 | 1.010 | −0.148 | −0.941 | 0.355 |

| post- | 3.74 | 0.764 | ||||

| I think that many people around the world are poor because they do not work hard enough. | pre- | 1.82 | 0.772 | −0.036 | −0.328 | 0.745 |

| post- | 1.86 | 0.803 | ||||

| I respect and am concerned with the rights of all people globally. | pre- | 4.30 | 0.724 | 0.148 | 1.072 | 0.294 |

| post- | 4.15 | 0.718 | ||||

| Developed/Developing nations have the obligation to make incomes around the world as equitable as possible | pre- | 3.43 | 0.879 | 0.107 | 0.550 | 0.587 |

| post- | 3.32 | 1.020 | ||||

| American/Turkish people should emulate the more sustainable and equitable behaviors of other developed/developing countries | pre- | 4.11 | 0.786 | −0.107 | −0.769 | 0.449 |

| post- | 4.21 | 0.738 | ||||

| I do not feel responsible for the world’s inequities and problems. | pre- | 2.64 | 1.062 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| post- | 2.64 | 1.193 | ||||

| I think in terms of giving back to the global society. | pre- | 3.71 | 0.937 | −0.036 | −0.238 | 0.813 |

| post- | 3.75 | 0.799 | ||||

| I am confident that I can thrive in any culture or country. | pre- | 3.61 | 1.066 | −0.214 | −0.902 | 0.375 |

| post- | 3.82 | 0.945 | ||||

| I know how to develop a place to help mitigate a global environmental or social problem. | pre- | 3.36 | 0.731 | −0.143 | −0.891 | 0.381 |

| post- | 3.50 | 0.745 | ||||

| I know several ways in which I can make a difference on some of this world’s most worrisome problems. | pre- | 3.43 | 0.920 | −0.107 | −0.682 | 0.501 |

| post- | 3.54 | 0.793 | ||||

| I am able to get other people to care about global problems that concern me. | pre- | 3.75 | 0.967 | −0.250 | −1.567 | 0.129 |

| post- | 4.00 | 0.609 | ||||

| I unconsciously adapt my behavior and mannerisms when I am interacting with people of other cultures. | pre- | 3.96 | 0.744 | −0.036 | −0.328 | 0.745 |

| post- | 4.00 | 0.720 | ||||

| I often adapt my communication style to other people’s cultural background | pre- | 3.71 | 0.763 | −0.393 | −2.645 | 0.013 ** |

| post- | 4.11 | 0.737 | ||||

| I am able to communicate in different ways with people from different cultures. | pre- | 3.79 | 0.630 | −0.429 | −3.057 | 0.005 *** |

| post- | 4.21 | 0.499 | ||||

| I am fluent in more than one language. | pre- | 2.71 | 1.410 | −0.179 | −1.307 | 0.202 |

| post- | 2.89 | 1.397 | ||||

| I welcome working with people who have different cultural values from me. | pre- | 4.52 | 0.580 | 0.148 | 1.162 | 0.256 |

| post- | 4.37 | 0.492 | ||||

| I am able to mediate interactions between people of different cultures by helping them understand each other’s values and practices. | pre- | 3.68 | 0.670 | −0.357 | −2.423 | 0.022 ** |

| post- | 4.04 | 0.508 | ||||

| I am informed of current issues that impact international relationships. | pre- | 3.59 | 0.797 | −0.222 | −2.280 | 0.031 ** |

| post- | 3.81 | 0.557 | ||||

| I feel comfortable expressing my views regarding a pressing global problem in front of a group of people. | pre- | 3.26 | 0.764 | −0.593 | −3.309 | 0.003 *** |

| post- | 3.85 | 0.770 | ||||

| I am able to write an opinion letter to a local media source expressing my concerns over global inequalities and issues. | pre- | 3.54 | 0.793 | −0.179 | −1.000 | 0.326 |

| post- | 3.71 | 0.810 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I plan to do volunteer work to help individuals and communities abroad. | pre- | 3.21 | 1.031 | −0.357 | −2.173 | 0.039 ** |

| post- | 3.57 | 0.920 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will participate in a walk, dance, run, or bike ride in support of a global cause. | pre- | 3.71 | 1.117 | −0.071 | −0.493 | 0.626 |

| post- | 3.79 | 0.995 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will volunteer my time working to help individuals or communities abroad. | pre- | 3.25 | 0.887 | −0.071 | −0.420 | 0.678 |

| post- | 3.32 | 0.945 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I plan to get involved with a global humanitarian organization or project. | pre- | 3.21 | 0.876 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| post- | 3.21 | 0.787 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I plan to help international people who are in difficulty. | pre- | 3.54 | 0.962 | 0.071 | 0.465 | 0.646 |

| post- | 3.46 | 0.881 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I plan to get involved in a program that addresses the global environmental crisis. | pre- | 3.46 | 0.999 | −0.036 | −0.238 | 0.813 |

| post- | 3.50 | 0.962 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will work informally with a group toward solving a global humanitarian problem. | pre- | 2.93 | 0.813 | −0.286 | −1.769 | 0.088 * |

| post- | 3.21 | 0.787 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will pay a membership or make a cash donation to a global charity. | pre- | 3.04 | 1.105 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| post- | 3.04 | 0.999 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will contact a newspaper or radio to express my concerns about global environmental, social, or political problems. | pre- | 2.32 | 0.819 | −0.357 | −1.987 | 0.057 * |

| post- | 2.68 | 0.945 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will express my views about international politics on a website, blog, or chat room. | pre- | 3.04 | 1.105 | −0.250 | −1.491 | 0.148 |

| post- | 3.29 | 0.937 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will sign an e-mail or written petition seeking to help individuals or communities abroad. | pre- | 3.29 | 1.049 | −0.071 | −0.386 | 0.702 |

| post- | 3.36 | 1.026 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will contact or visit someone in government to seek public action on global issues and concerns. | pre- | 2.43 | 0.836 | −0.143 | −1.000 | 0.326 |

| post- | 2.57 | 0.790 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will display and/or wear badges/stickers/signs that promote a more just and equitable world. | pre- | 3.14 | 1.044 | −0.429 | −2.714 | 0.011 ** |

| post- | 3.57 | 0.879 | ||||

| Over the next 6 months. I will participate in a campus forum. Live music or theater performance or other event where young people express their views about global problems. | pre- | 3.57 | 0.959 | −0.036 | −0.197 | 0.846 |

| post- | 3.61 | 0.832 | ||||

| If at all possible. I will always buy fair-trade or locally grown products and brands. | pre- | 4.07 | 0.858 | −0.036 | −0.273 | 0.787 |

| post- | 4.11 | 0.737 | ||||

| I will deliberately buy brands and products that are known to be good stewards of marginalized people and places. | pre- | 3.79 | 0.876 | 0.071 | 0.493 | 0.626 |

| post- | 3.71 | 0.854 | ||||

| I will boycott brands or products that are known to harm marginalized global people and places. | pre- | 3.71 | 0.854 | 0.107 | 0.648 | 0.523 |

| post- | 3.61 | 0.916 | ||||

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development 2005–2014. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001416/141629e.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2013).

- Oxfam. Education for Global Citizenship: A Guide for Schools. Available online: http://www.oxfam.org.uk/~/media/Files/Education/Global%20Citizenship/education_for_global_citizenship_a_guide_for_schools.ashx (accessed on 8 September 2013).

- Henry, A.D. The challenge of learning for sustainability: A prolegomenon to theory. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2009, 16, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, D.; Ogazon, A. The challenges of sustainability education. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2011, 3, 1947–2900. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, D.B.; Ogden, A.C. Initial development and validation of the Global Citizenship Scale. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2011, 15, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vann, J.; Pacheco, P.; Motloch, J. Cross-cultural education for sustainability: Development of an introduction to sustainability course. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Selby, D.; Sterling, S. Introduction. In Sustainability Education: Perspectives and Practice Across Higher Education; Jones, P., Selby, D., Sterling, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- The Scottish Government. Learning for Change: Scotland’s Action Plan for the Second Half of the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2010/05/20152453/2 (accessed on 8 September 2013).

- ARIES. Education for Sustainability. Macquire University. Available online: http://aries.mq.edu.au/publications/aries/efs_brochure/pdf/efs_brochure.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2013).

- Jones, P.; Trier, C.J.; Richards, J.P. Embedding education for sustainable development in higher education: A Case study examining common challenges and opportunities for undergraduate programmes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2008, 47, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Isacsson, A.; Matarrita, D.; Wainio, E. Teaching based on TEFI values: A case study. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2011, 11, 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chalkley, B.; Blumhof, J.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V. Geography earth and environmental sciences: A suitable home for ESD? In Sustainability Education: Perspectives and Practice Across Higher Education; Jones, P., Selby, D., Sterling, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tilbury, D. Higher education for sustainability: A global overview of commitment and progress. In Higher Education’s Commitment to Sustainability: From Understanding to Action; Global University Network for Innovation (GUNI), Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Eames, M.T. At the crossroads: Teaching sustainability at university. A comparison of experiences from Kingston and Olderburg Universities. In Developing Sustainability; Comby, J., Eames, K.A.T., Tirlani, V., Guihery, L., Gomez, J.M., Öktem, A.U., Eds.; Istanbul Bilgi University Press: Istanbul, Turkey, 2013; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Incorporation and institutionalization of SD into universities: Breaking through barriers to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidgren, A.; Rodhe, H.; Huisingh, D. A systemic approach to incorporate sustainability into university courses and curricula. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, D.; Winter, J. It’s not just bits of paper and light bulbs: A Review of sustainability pedagogies and their potential for use in higher education. In Sustainability Education: Perspectives and Practice Across Higher Education; Jones, P., Selby, D., Sterling, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.; Small, J. TEFI 6, June 28–30, 2012, Milan, Italy: Transformational leadership for tourism education. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2013, 13, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blottnitz, H.V. Promoting active learning in sustainable development: Experiences from a 4th year chemical engineering course. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Higher education, sustainability, and the role of systemic learning. In Higher Education and the Challenge of Sustainability: Problematics, Promise, and Practice; Corcoran, P.E., Wals, J., Arjen, E., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Hingham, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lugg, A. Developing sustainability-literate citizens through outdoor learning: Possibilities for outdoor education in Higher Education. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2007, 7, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism and sustainable development: Exploring the theoretical divide. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Sustainable performance index for tourism policy development. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canziani, B.F.; Sönmez, S.; Hsien, Y.; Byrd, E.T. A learning theory framework for sustainability education in tourism. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2012, 12, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Society of Sustainability Professionals (ISSP). The Sustainability Professional: 2010 Competency Survey Report 2010. Available online: http://www.sustainabilityprofessionals.org/sustainability-professional-2010-competency-survey-report (accessed on 8 October 2013).

- Sheldon, P.J.; Fesenmaier, D.R; Tribe, J. The tourism education futures initiative (TEFI): Activating change in tourism education. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2011, 11, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leihy, P.; Salazar, J. Education for Sustainability in University Curricula: Policies and Practice in Victoria; Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Teaching and Learning for a Sustainable FutureSustainable Tourism. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/education/tlsf/mods/theme_c/mod16.html (accessed on 8 September 2013).

- Junyent, M.; Geli de Ciurana, A.M. Education for sustainability in university studies: A model for reorienting the curriculum. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 34, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.; Fesenmaier, D.; Woeber, K.; Cooper, C.; Antonioli, M. Tourism education futures, 2010–2030: Building the capacity to lead. J. Teach. Tour. Travel 2008, 7, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Vogelaar, A.; Hale, B.W. Toward sustainable educational travel. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 22, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, L. Global citizenship, global health, and the internationalization of curriculum: A study of transformative potential. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2010, 14, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, B.; White, G.P.; Godbey, G.C. What does it mean to be globally competent? J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2006, 10, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braskamp, L.A. Developing global citizens. J. Coll. Character 2008, 10, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Paige, R.M.; Fry, G.W.; Stallman, E.M.; Josic, J.; Jon, J.-E. Study abroad for global engagement: The long-term impact of mobility experiences. Intercult. Educ. 2009, 20, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.; Rowe, A.L.; Thomas, G.; Klass, D. Weaving sustainability into business education. J. Asia Pac. Cent. Environ. Account. 2008, 14, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, G.R.; Kensbock, S.; Kachel, U. Enhancing “Education about and for sustainability” in a tourism studies enterprise management course: An action research approach. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2010, 10, 163–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deale, C.S.; Barber, N. How important is sustainability education to hospitality programs? J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2012, 12, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, M.A.; Rubin, D.L.; Stoner, L. The added value of study abroad: Fostering a global citizenry. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2014, 18, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, M.A.; Lyons, K.; Stoner, L.; Kyle, G.T.; Wearing, S.; Poudyal, N. Global citizenry, educational travel and sustainable tourism: Evidence from Australia and New Zealand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 22, 403–420. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of International Education. Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange. Available online: http://www.iiebooks.org/opdoreonined.html (accessed on 3 September 2013).

- Moscardo, G.; Murphy, L. There is no such thing as sustainable tourism: Re-conceptualising tourism as a tool for sustainability. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2538–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happiness Alliance. Happiness Report Card for Seattle. Available online: http://www.happycounts.org/wp-system/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2011/11/Seattle-Happiness_Report_Card-2011.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2013).

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Tourism Strategy of Turkey 2023. Available online: http://www.kulturturizm.gov.tr/genel/text/eng/TST2023.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2013).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). City of Safranbolu. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/614 (accessed on 3 October 2013).

- Padurean, L.; Maggi, R. TEFI values in tourism education: A comparative analysis. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2011, 11, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Zahra, A. A cultural encounter through volunteer tourism: Towards the ideals of sustainable tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hatipoglu, B.; Ertuna, B.; Sasidharan, V. A Referential Methodology for Education on Sustainable Tourism Development. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5029-5048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6085029

Hatipoglu B, Ertuna B, Sasidharan V. A Referential Methodology for Education on Sustainable Tourism Development. Sustainability. 2014; 6(8):5029-5048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6085029

Chicago/Turabian StyleHatipoglu, Burcin, Bengi Ertuna, and Vinod Sasidharan. 2014. "A Referential Methodology for Education on Sustainable Tourism Development" Sustainability 6, no. 8: 5029-5048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6085029

APA StyleHatipoglu, B., Ertuna, B., & Sasidharan, V. (2014). A Referential Methodology for Education on Sustainable Tourism Development. Sustainability, 6(8), 5029-5048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6085029