Cultural Resources as Sustainability Enablers: Towards a Community-Based Cultural Heritage Resources Management (COBACHREM) Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainability

“…to adopt a general policy which aims to give the cultural and natural heritage a function in the life of the community and to integrate the protection of that heritage into comprehensive planning programs” is one component that is targeted through the COBACHREM.

| Competency | Examples of possible titles for curriculum development within COBACHREM | Examples of possible outcomes for learner members of community |

|---|---|---|

| A. Core |

|

|

| B. Support |

|

|

| C. General |

|

|

2. Conceptualizing Community Participation: Social Agency as a Cultural Reproduction Process

“Social intentionality is necessary if social life is to occur. Agency must adapt to and promulgate social patterns. Otherwise, there would be no common, stable, or predictable social life. Qualitative social change is possible, however only if individuals are socially oriented to cooperate in mass movements to transform the social organization of activities and associated cultural concepts ...” emphasizing the relevance of a collective community (community participation) in cultural production and reproduction.

3. Results and Discussion

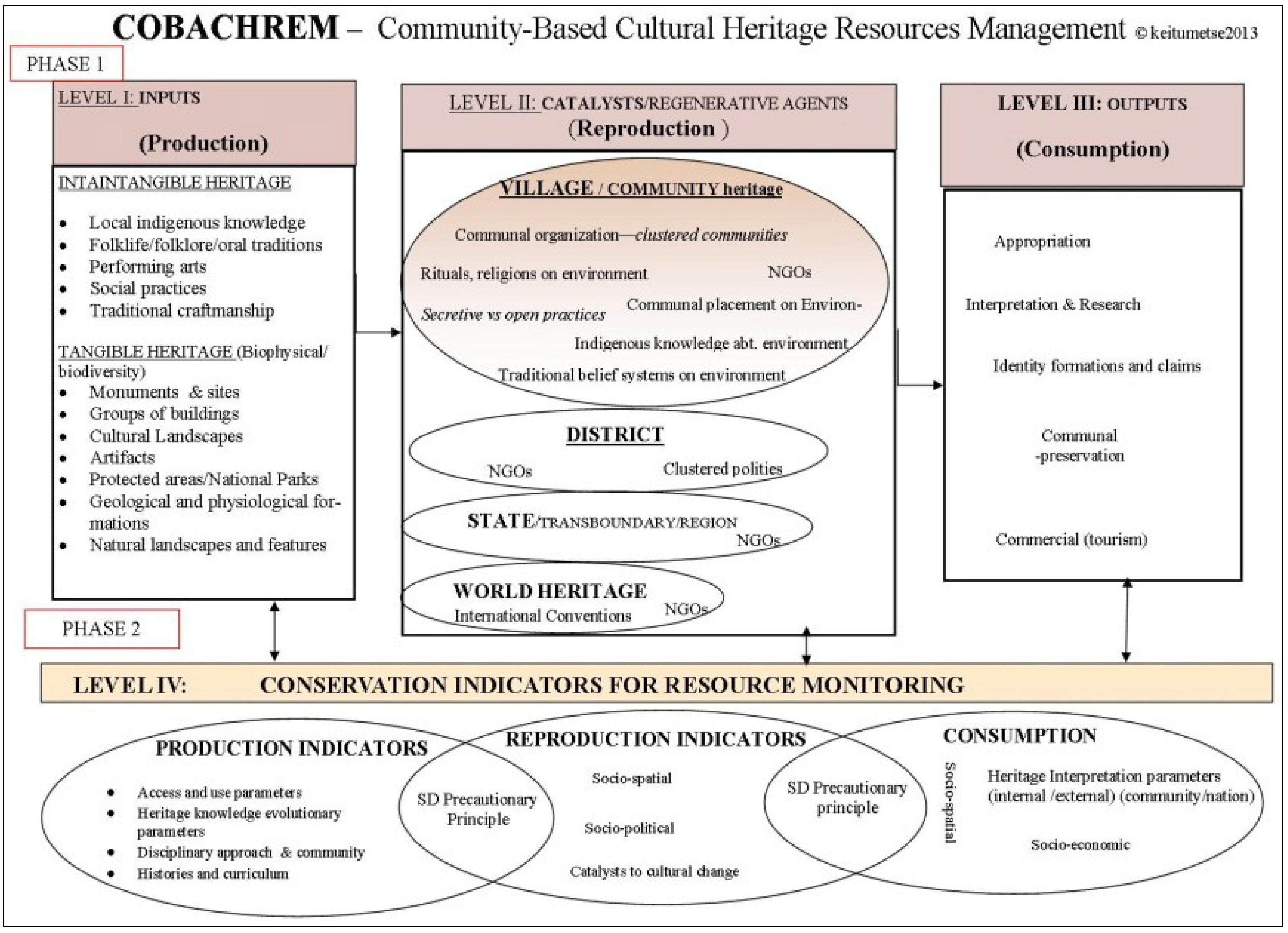

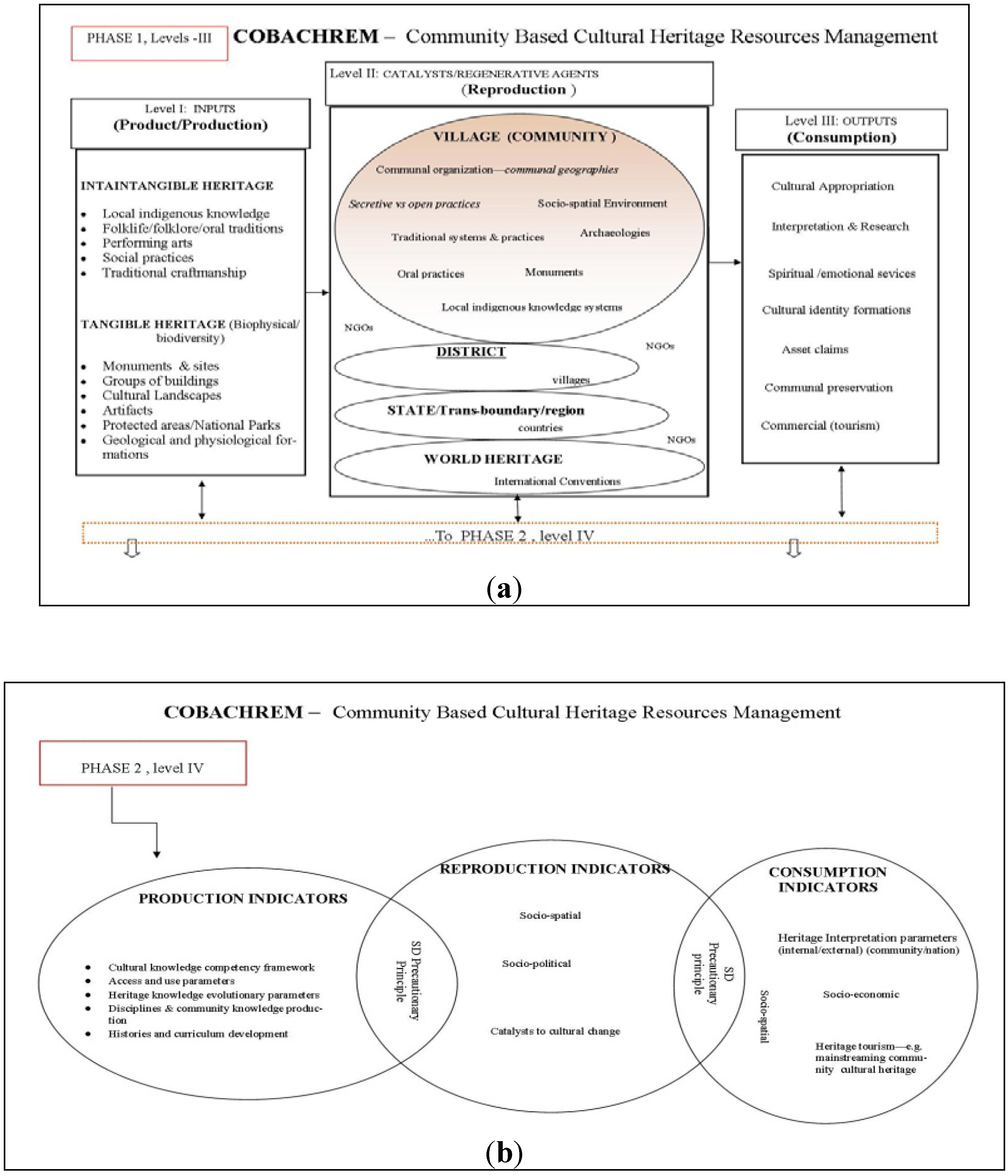

3.1. COBACHREM: The Model and Descriptions of Levels of Operation

- Phase 1: Devises a 6 community-based cultural heritage resources management (COBACHREM) framework that isolates and outlines production (inputs), reproduction (regeneration) and consumption (outputs) indicators specific to cultural and heritage resources as a process that enables efficient monitoring of activities that affect the use and re-use of cultural resources at community levels. This process will also facilitate development of monitoring strategies specific to cultural and heritage resources—e.g., example of phase 2 below.

- Phase 2: The development of operational guidelines (indicators) from the isolated parameters in phase 1 of the model necessitates monitoring approaches and tools for activities in levels I–III. In this article, two examples of monitoring tools provided are (i) a development of competency-based education training using people’s cultural competency; and (ii) mainstreaming of community cultural competency into an already existing eco-certification process.

- Level I (Product/production): identifies the foundation upon which cultural heritage resources exist and are contained, i.e., environment as container and cultural environment as a product. Borrowing from Soja ([20], p. 209) we will call this “... space per se, or contextual space ...”. The Main divergent categories of cultural resources are identified and isolated into distinct categories such as tangible and intangible cultural heritage to enable distinct separation of conservation indicators going forward.

- Level II (Reproduction/Regeneration): identifies stakeholders that interact with cultural heritage, including grassroots communities. The stakeholders represent reproductive/regenerative agents or socio-spatial catalysts that interact with cultural heritage resources and give them meaning. Issues of whose heritage, who uses heritage, for what and why are common here. A socio-spatial placement and representation of cultural heritage within sectors and regions is considered. Local heritage transformation to world heritage in what can be termed the geographical transfer of value [20] is prevalent at this stage, where community interaction with cultural resources is redefined. Setting catalytic limits is necessary here to maintain resource authenticity; and benchmark the scale (catalytic stretch) at which inputs are influenced by various stakeholders for monitoring in the future. This is equivalent to limits of acceptable change concept in natural resources management [21]. It is here where communities are faced with competition for use of their cultural heritage knowledge and where cultural bearers require sensitization and empowerment through new strategies such as COBACHREM to give them a competitive advantage through their cultural competency.

- Level III—Consumption—Again borrowing from Soja [20] we will call this the “... socially-based spatiality, the created space of social organization and production”, where appropriation of cultural resources through various uses by regenerative agents in level II is at its highest. Consumption of heritage takes the form of identity affiliation, use in claims to resources such as land; traditional practices, ritual practices, religious practice, use in cultural heritage tourism, to mention but a few.

- Level IV—Monitoring is where conservation indicators for each of levels I–III are developed based on identified characteristics of cultural resources that require various conservation approaches. For example in level II, indicators that will maintain product authenticity are key; while for level III indicators that limit catalysis to acceptable standards of resource use are encouraged. Finally for level IV, indicators that will maintain a sustainable consumption of cultural resources are sought.

3.2. Examples of Identity Formation Concepts for COBACHREM Model: Indigenity and Autochthony Case Studies

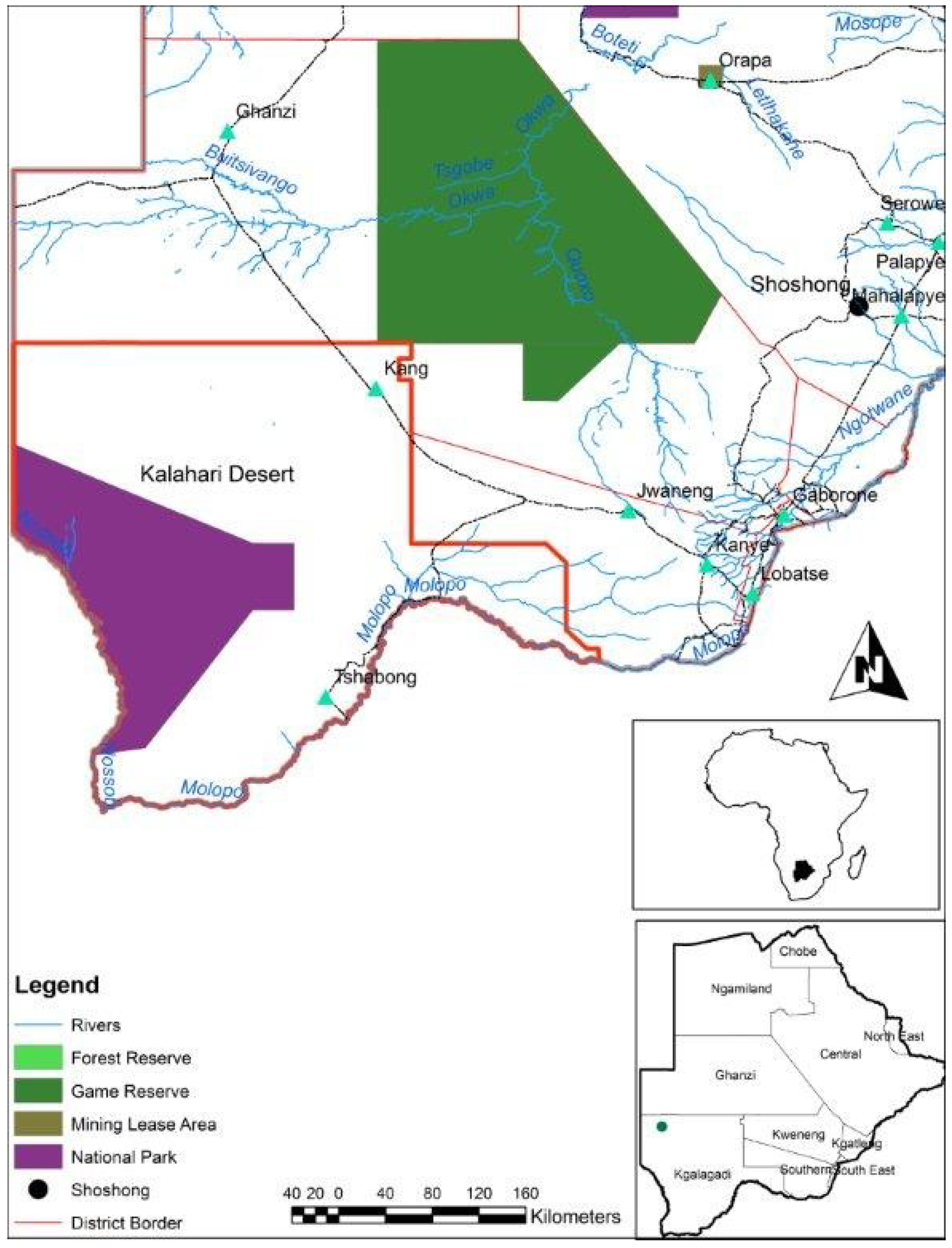

3.2.1. Indigenity Concept: Kgalagadi Desert People, Botswana

“Tribal peoples in independent countries whose social, cultural and economic conditions distinguish them from other sections of the national community, and whose status is regulated wholly or partially by their own customs or traditions or by special laws or regulation”.[22]

- Level I (production)—physical environment (locality) or “… contextual space” as characterized by Soja [20]—within Botswana San/Bushmen being commonly Kgalagadi desert areas (Figure 3), which by virtue of its distinctiveness determines the constitution of tangible and intangible cultural heritage of the community in question. This comes from the fact that a community work on what it has in terms of environment, not necessarily on the fact that the environment determines what becomes heritage about a community because some skills that are brought to an environment have been innovated outside that environment but ultimately alters it to a particular heritage context.

- Level II (reproduction)—identification of stakeholders that interact with indigenous cultures and communities, in order to assess evolutionary direction of a community heritage resulting from the interaction. Considering indigenous communities as “… first inhabitants of a given territory, or at least to have occupied it prior to successive waves of settlers” [18], stakeholders in a country such as Botswana can be traced to kingdom/chiefdom status, European explorers, missionaries, to mention but a few. Events that will have brought more stakeholders and influenced the shape of indigenous communities’ cultures may include pre-colonial regional wars such as Mfecane [23] which will have pushed them into environmental frontiers that prompted a revised cultural context, modifying cultural identities from the authentic ones. Many other events will follow including colonial period, nation-state building period, and current democracy model, all of which bring along different stakeholders that require identification in order to determine factors that influenced change in authentic cultural context and its resuscitation where necessary. In addition, identification of stakeholders also enables a temporal tracking of their influence on indigenous communities’ cultural consumption in step III. The outcome of the identification of stakeholders and/or events process is later used to benchmark the degree of dilution of cultural context as a step towards a more representative cultural component for the community.

- Level III (Consumption)—With some of the characteristics of indegenity being native occupation of land and marginalization, examples of the catalytic stretches of cultural heritage may include the degree/scale of contact with identified stakeholders in II, while catalytic limits can be drawn from temporal parameters of the before-after contact. In instances where catalytic limits may already have been exceeded, intangible heritage from memory and archaeological data become necessary to determine the boundaries of cultural identity resuscitation, reconstruction and restoration.

- Level IV—Monitoring of catalytic limits identified through steps II-III takes places at this stage as a sustainable conservation approach. An example within indigenous concept include implementing sustainable cultural consumption methods such as keeping sacred knowledge sacred, slowing the scale of extinction of varying cultural domains such as hunting songs, to mention but a few.

3.2.2. Autochthony Concept: Shoshong Village People, Botswana

- Level I (production)—village settlement history discerned with a focus on various historical locations and events characterizing the existing multiple communal identities.

- Level II (reproduction)—reproductive agents of cultural heritage are first traced through historical origins, political and economic history. Communal mapping becomes a pre-requisite at this stage. Many other events will follow including colonial period, nation-state building period, and current democracy model, all of which bring along different stakeholders that require identification in order to determine factors that influenced change in authentic cultural context and its resuscitation where necessary. Village to state level stakeholders are crucial.

- Level III (Consumption)—identification of heritage that is common and neutral to the two communities that have physical presence in the landscape followed by the community with a virtual presence on the landscape. Communities that are “living the environment” possess a sense of place to the landscape and that should be prioritized.

- Level IV (Monitoring indicators)—conservation indicators are developed for historical processes and events identified in steps I–III to sustain communal and social cultural democracy.

3.3. Examples of Phase 2, Level IV: Monitoring Initiatives derived from Production, Reproduction and Consumption Levels in Figure 2

| Example of ecotourism and eco-certification attributes Botswana Eco-certification (2010) principles | Select examples of community cultural competency that can be tapped through COBACHREM approach |

|---|---|

| 1. Policies relating to conservation of both wilderness and wildlife resources |

|

| 2. Physical design and operations |

|

| 3. Visitor experience, impact |

|

| 4. Maximizing local community and districts benefits |

|

| 5. Conservation |

|

| 6. Ecotours (nature interpretation) |

|

4. Conclusions

- Advance planned use of cultural and heritage resources in poverty alleviation strategies to add value to existing conservation initiatives within natural resources.

- Use cultural resources management process (COBACHREM) to diversify communal resource uses in a way that curb competition, and subsequently conflicts, surrounding the use of natural resources in poverty stricken environments such as African wetlands like the Okavango Delta area of Botswana.

- Facilitate the building of sustainable communities in rural landscapes by using cultural resources to connect people to their historic and natural environments in a spiritual, emotional and economic manner expedited through recognition of cultural competency. The approach reduces pressure from overuse of wilderness and wildlife resources.

- Provide cultural resources as alternative resources to curb communal poverty in rural areas of developing countries.

- Merge the technical (model) and academic (concepts indigenity, autochthony) aspects of cultural resources use to come up with sustainable management approaches.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agenda 21 and the UNCED Proceedings; Third Series: International Protection of the Environment; Volume 6, Robinson, N.A.; Hassan, P.; Burhenne-Guilmin, F. (Eds.) Oceana: New York, NY, USA, 1993.

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Laplante, B.; Meisner, C.; Wang, H. Environment as Cultural Heritage: The Armenian Diaspora’s Willingness to Pay to Protect Armenia’s Lake Sevan; Working Paper 3520; World Bank Policy Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 3520. [Google Scholar]

- Hammani, F. Culture and planning for change and continuity in Botswana. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2012, 32, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitumetse, S.O. Sustainable development and cultural heritage management in Botswana: Towards sustainable communities. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 19, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitumetse, S.O. Sustainable Development and Archaeological Heritage Management: Local Community Participation and Monument Tourism in Botswana. Ph.D. Thesis, Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage. the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Meeting, Paris, France, 16 November 1972; Available online: http://whc.unesco.org (accessed on 10 September 2013).

- UNESCO 2003. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Meeting, Paris, France, 17 October 2003; Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/ (accessed on 10 September 2013).

- UNESCO 1989. On Technical and Vocational Education. the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Meeting, Paris, France, 10 November 1989; Available online: http://www.unesco.org/education/nfsunesco/pdf/TECVOC (accessed on 10 September 2013).

- Keitumetse, S. Celebrating or Marketing the Indigenous? International Rights Organisations, National Governments and Tourism Creation. In Tourism and Politics: Global Frameworks and Local Realities; Burns, M., Novelli, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelands, L.; Clair, L.S. Toward an empirical concept of group. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 1993, 23, 423–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfali, B. Active minorities and social representations: Two theories, one epistemology. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2002, 32, 396–412. [Google Scholar]

- Ratner, C. Agency and culture. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2000, 30, 413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Ramahobo, N. Minority Tribes in Botswana: The Politics of Recognition; Minority Rights Group International: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the Indigenous and Tribal People Convention, 1989 (No. 169)—Handbook for ILO Tripartite Constituents. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/standards/subjects-covered-by-international-labour-standards/indigenous-and-tribal-peoples/WCMS_205225/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 29 November 2013).

- Midgley, J. Community Participation: History, Concepts and Controversies. In Community Participation, Social Development and the State; Midgley, J., Ed.; Methuen: London, UK, 1986; pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, R. Ecology and Economics: An Approach to Sustainable Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gausset, Q.; Kenrick, J.; Gibb, R. Indigeneity and autochthony: A couple of false twins? Soc. Anthropol. 2011, 19, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgers, M. Autochthony as capital in a global age. Theory Cult. Soc. 2011, 28, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. The socio-spatial dialectic. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1980, 70, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankey, G.H.; Cole, D.N.; Lucas, R.C.; Peterson, M.E.; Frissel, S.S. Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) System for Wilderness Planning; General Technical Report INT-176; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Available online: http://www.ilo.org (accessed on 10 September 2013).

- Eldredge, E. Sources of conflicts in Southern Africa, c. 1800–30: The “mfecane”. J. Afr. Hist. 1992, 33, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vubo, E.Y. Niveaux de conscience historique. Development de l’identite ethnicite au Cameroun. Cahiers d’Etudes Africaines 2003, 43, 591–628. (in French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebanne, A.M.; Monaka, K.C. Mapping shekgalagari in Southern Africa: A socio-historical and linguistic study. Hist. Afr. 2008, 35, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncongco, L. Origins of the Tswana. Pula: Botswana J. Afr. Stud. 2003, 1, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Botswana Training Authority (BOTA). Manual for Development of Botswana National Vocational Qualifications Framework (BNVQF) Unit Standards; BOTA: Gaborone, Botswana, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NQA). Guidance and Examples for NQF Unit Standards; NQA: Wellington, New Zealand, 2004.

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Keitumetse, S.O. Cultural Resources as Sustainability Enablers: Towards a Community-Based Cultural Heritage Resources Management (COBACHREM) Model. Sustainability 2014, 6, 70-85. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6010070

Keitumetse SO. Cultural Resources as Sustainability Enablers: Towards a Community-Based Cultural Heritage Resources Management (COBACHREM) Model. Sustainability. 2014; 6(1):70-85. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6010070

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeitumetse, Susan O. 2014. "Cultural Resources as Sustainability Enablers: Towards a Community-Based Cultural Heritage Resources Management (COBACHREM) Model" Sustainability 6, no. 1: 70-85. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6010070

APA StyleKeitumetse, S. O. (2014). Cultural Resources as Sustainability Enablers: Towards a Community-Based Cultural Heritage Resources Management (COBACHREM) Model. Sustainability, 6(1), 70-85. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6010070