Avoiding the Limits to Growth: Gross National Happiness in Bhutan as a Model for Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

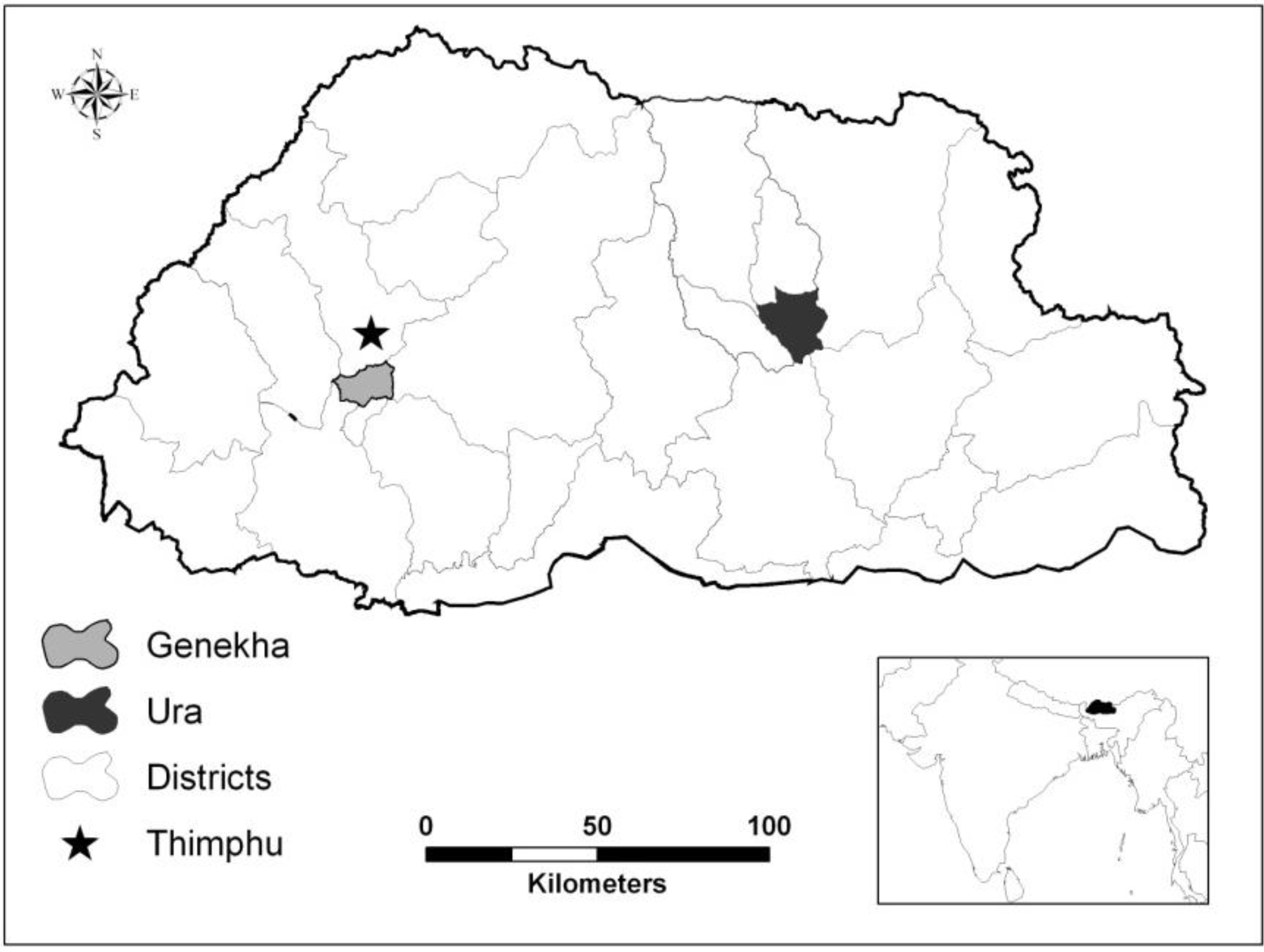

2. The 30-Year Update to Limits to Growth—Recommendations for Moving towards Sustainability

3. Study Site and Methods

4. How Can the System Be Changed?

4.1. New Perspectives on Development

“…a sustainable society would be interested in qualitative development, not physical expansion. It would use material growth as a considered tool, not a perpetual mandate. Neither for nor against growth, it would begin to discriminate among kinds of growth and purposes for growth…it would ask what the growth is for, and who would benefit…and whether the growth could be accommodated by the sources and sinks of the earth.”([1], p. 255)

Gross National Happiness in Bhutan

“…achieve a balance between the spiritual and material aspects of life, between peljor gomphel (economic development) and gakid (happiness and peace). When tensions were observed between them, we have deliberately chosen to give preference to happiness and peace, even at the expense of economic growth, which we have regarded not as an end in itself, but as a means to achieve improvements in the well-being and welfare of the people.”([39], p. 19)

| Indicator | Prior level (year) | Current level & projections |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of underweight children under 5 yrs | 17% (1999) | 12.7% (2010) projected 9% in 2012 |

| Proportion of population living below minimum level of dietary energy consumption | 3.8% (2003) | 5.9% (2007) projected 1.9% in 2012 |

| Proportion of population living below poverty line | 31.7% (2003) | 23.2% (2007) projected 15% in 2012 |

| Income inequality (Gini) | 0.416 (2003) | 0.352 (2007) |

| Unemployment | 1.9% (2001) | 3.1% (2011) |

| Percentage of households with electricity | 54% (2007) | 73% (2011) projected 100% in 2013 |

| Percentage of women in Civil Service | 21.2% (2000) | 31.62% (2010) |

| Maternal mortality rate (per 100,000 live births) | 255 (2000) | 140 (2012) |

| Percentage of births covered by skilled attendants | 24% (2000) | 64.5% (2010) projected 90% in 2012 |

| Total fertility rate | 4.7 (2000) | 2.6 (2010) |

| Infant mortality rate (per 1,000 live births) | 70.7 (1999) | 47 (2010) projected 25 in 2012 |

| Number of doctors (per 1000 of population)A | 0.13 (2005) | 0.26 (2010) |

| Percentage of population with access to safe drinking water | 68 (2001) | 96 (2010) projected 100% in 2012 |

| Percentage of population with access to sanitation | 88 (2000) | 93 (2010) projected 95% in 2012 |

| Net primary school enrollment | 62% (2000) | 93.7% (2010) projected 100% in 2012 |

| Gender parity in primary education | 82% (2000) | 99.4% (2010) |

| Gender parity in secondary education | 78% (2000) | 103.5% (2010) |

| Adult literacy rate | 52.8% (2005) | Projected 65% in 2012 |

4.2. New Metrics for Development

“…sustainable society is one that has in place informational, social, and institutional mechanisms to keep in check the positive feedback loops that cause exponential population and capital growth.”([1], p. 254)

“Learn about and monitor both the real welfare of the human population, and the real impact on the world ecosystem of human activity. Inform governments and the public as continuously and promptly about environmental and social conditions as about economic conditions. Include environmental and social costs in economic prices; recast economic indicators such as the GDP, so that they do not confuse costs with benefits or throughput with welfare or the deterioration of natural capital with income”.([1], p. 259)

Gross National Happiness Index

“… coordinate the formulation of all policies, plans and programmes in the country and ensure that GNH is mainstreamed into the planning, policy making and implementation process by evaluating their relevance to the GNH framework.”[65]

| Domains | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Education |

|

| Health |

|

| Ecological diversity and resilience |

|

| Good governance |

|

| Time Use |

|

| Cultural diversity and resilience |

|

| Community Vitality |

|

| Psychological well-being |

|

| Living standards |

|

4.3. Changes in Social Structures

“The emergence of Bhutan as a nation state has been dependent upon the articulation of a distinct Bhutanese identity, founded upon our Buddhist beliefs and values... This identity, manifest in the concept of ‘one nation, one people’, has engendered in us the will to survive as a nation state… It is a unity that binds us all together and enables us to share a common sense of identity.”([39], p. 1)

“There are more religious people these days because there is more awareness of the teachings and preachings. Now there are more shedras (monk school of the Nyingmapa tradition of Buddhism) which are increasing the awareness of the community.”[81]

“Compared to the past, there are more religious people now because the teachings are more common. People are more aware now because they can hear teachings through the media [radio and newspapers].”[82]

“Religious people have increased over the years because nowadays there are a lot of great saints and lamas that are coming and giving preachings. The current Je Khempo (Chief Abbot of the Central Monastic Body of Bhutan) is giving more teachings in rural areas now, so people are more aware. Even small kids are aware of good and bad deeds.”[83]

“Nowadays religion has increased because everyone goes to school and they are educated. Religion is incorporated into the curriculum and they teach values also. People are learning and there are 10 Geylongs (lay monks) now here whereas in the past there weren’t any.”[84]

5. The Challenges ahead for Bhutan

“It depends on the person and the way he thinks. If he’s kind enough, he’s happy when people get better off. But some, they are competitive. When one family does better, their neighbors feel like they need to do better.”[89]

When asked whether people desire things more now that in the past, one woman responded that people:“In the past, people were more cooled down. Now that the country is developing, people’s hearts are getting harder. Now with development, there is a chance for wealth and people have to fight for wealth so they are that way now.”[90]

Another participant in a focus group meeting in a village in central Bhutan stated:“…don’t feel jealous when people get new equipment, but what they think is that I would also be happy if I could buy such things. It doesn’t make them unhappy, but they wish they could also buy things, so if they can afford to buy it, they will.”[91]

“now people are starting to wear fashionable ghos and kiras (traditional male and female dress) and their kids want expensive things. Before everything was simple.”[84]

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Meadows, D.H.; Randers, J.; Meadows, D. Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update; Chelsea Green Publishing Co.: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Macgregor, J.A.; Camfield, L.; Woodcock, A. Needs, wants and goals: wellbeing, quality of life and public policy. App. Res. Qual. Life 2009, 4, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max-Neef, M.; Elizalde, A.; Hopenhayn, M.; Herrea, F.; Zemelman, H.; Jatoba, J.; Weinstein, L. Human scale development: An option for the future. Dev. Dialogue 1989, 1, 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, G.M. A comparison of The Limits to Growth with 30 years of reality. Global Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, M.C.; Hall, C.A.S.; O’Connor, P.; Cleveland, C.J. A New Long Term Assessment of Energy Return on Investment (EROI) for U.S. Oil and Gas Discovery and Production. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1866–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, I. The end of Peak Oil? Why this topic is still relevant despite recent denials. Energ. Policy 2013, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lenton, T.M.; Held, H.; Krieger, E.; Hall, J.W.; Lucht, W.; Rahmstorf, S.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. General Electric Investing Billions to Improve Oil and Gas Drilling. Los Angeles Times. 28 May 2013. Available online: http://articles.latimes.com/2013/may/28/business/la-fi-mo-general-electric-fracking-20130528 (accessed on 4 August 2013).

- Howarth, R.; Ingraffea, A. Should fracking stop? Yes, it’s too high risk. Nature 2011, 477, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J. New technology propels “old energy” boom. R&D Magazine. 6 May 2013. Available online: http://www.rdmag.com/news/2013/05/new-technology-propels-%E2%80%9Cold-energy%E2%80%9D-boom (accessed on 2 August 2013).

- Jenkins, J.; Norhaus, T.; Shellenberger, M. “Energy Emergence: Rebound and Backfire as Emergent Phenomena”—Report Overview. The Breakthrough Institute 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Societal transformations for a sustainable economy. Nat. Resour. Forum 2011, 35, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Risk Governance Council, The Rebound Effect: Implications of Consumer Behaviour for Robust Energy Policies; International Risk Governance Council: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2013.

- Myers, N.; Kent, J. The New Consumers: The Influence of Affluence on the Environment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, C.L. Rising consumption of meat and milk in developing countries has created a new food revolution. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3907S–3910S. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.E. Economics in a full world. Sci. Amer. 2005, 293, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speth, J.G. The Bridge at the End of the World: Capitalism, the Environment, and Crossing from Crisis to Sustainability; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity Without Growth: Economics For a Finite Planet; Earthscan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deiner, E.; Seligman, M.E.P. Beyond money: toward an economy of well-being. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2004, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Census Commissioner, Results of Population and Housing Census of Bhutan 2005; Kuensel Corporation: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2005.

- Mathou, T. The politics of Bhutan: change in continuity. J. Bhutan Stud. 2000, 2, 250–262. [Google Scholar]

- B Brunet, S.; Bauer, J.; de Lacy, T.; Tshering, K. Tourism development in Bhutan: tensions between tradition and modernity. J. Sustain. Tourism 2001, 9, 242–263. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S. Developing Bhutan's economy: limited options, sensible choices. Asian Surv. 1989, 29, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangyal, T. Ensuring social sustainability: can Bhutan’s education system ensure intergenerational transmission of values? J. Bhutan Stud. 2001, 3, 106–131. [Google Scholar]

- Priesner, S. Bhutan in 1997: striving for sustainability. Asian Surv. 1998, 38, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.S. Buddhism, economics, and environmental values: A multilevel analysis of sustainable development efforts in Bhutan. Soc. Natur. Resour. 2011, 24, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.S. Economic and social dimensions of environmental behavior: balancing conservation and development in Bhutan. Conse. Biol. 2010, 24, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S. Human Development: Definitions, Critiques, and Related Concepts: Background Paper for the 2010 Human Development Report; Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. The GDP paradox. J. Econ. Psych. 2009, 30, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.K. Development as Capability Expansion. In Human Development and the International Development Strategy for the 1990s; Knight, G.A., Ed.; MacMillan: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Soubbotina, T.P.; Sheram, K.A. Beyond Economic Growth: Meeting the Challenges of Global Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.A. Visions of Development: A Study of Human Values; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A.K. Development as Freedom; Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, G. Invoking the Spirit: Religion and Spirituality in the Quest for a Sustainable World; Worldwatch Institute Paper 164; WorldWatch Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Planning Commission Secretariat, Bhutan 2020: A Vision for Peace, Prosperity, and Happiness Part II; Royal Government of Bhutan: Thipmhu, Bhutan, 1999.

- Ura, K.; Alkire, S.; Zangmo, T. Gross National Happiness and the GNH Index. In World Happiness Report; Helliwell, J., Layard, E., Sachs, J., Eds.; Earth Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gross National Happiness Commission. Five Year Plan. Available online: http://www.gnhc.gov.bt/five-year-plan/ (accessed on 12 June 2013).

- Rinzin, C. On the Middle Path: The Social Basis for Sustainable Development in Bhutan; Labor Grafimedia b.v.: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 352. [Google Scholar]

- Planning Commission Secretariat, Bhutan 2020: A Vision for Peace, Prosperity, and Happiness Part I; Royal Government of Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 1999.

- National Environment Comission, Bhutan Environment Outlook; National Environment Commission Secretariat, Royal Government of Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2008.

- Harnessing Hydropower. Available online: http://gofar.sg/bhutan/2012/11/harnessing-hydropower (accessed on 27 June 2013).

- Duba, S.; Ghimiray, M.; Gurung, T.R. Promoting Organic Farming in Bhutan: A Review of Policy, Implementation and Constraints; Council for Renewable Natural Resource Research Bhutan, Ministry of Agriculture, Royal Government of Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2008.

- Vidal, J.; Kelly, A. Bhutan set to plough lone furrow as world’s first wholly organic country. The Guardian-Poverty Matters Blog. 11 February 2013. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2013/feb/11/bhutan-first-wholly-organic-country (accessed on 20 June 2013).

- Clark, L.; Choegyal, L. Bhutan National Ecotourism Strategy; Keen Publishing Co., Ltd: Bangkok, Thailand, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forests. Department of Forests and Park Services. Available online: http://www.moaf.gov.bt/moaf/?page_id=83 (accessed on 2 June 2013).

- Walcott, S. Urbanization in Bhutabn. Geogr. Rev. 2009, 99, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Community-Based Natural Resource Management in Bhutan: A Framework; Department of Research and Development, Royal Government of Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2002; pp. 1–93.

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, J.S.; Tshering, D. A respected central government and other obstacles to community-based management of the matsutake mushroom in Bhutan. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross National Happiness Commission, SAARC Development Goals Mid-Term Review Report; Gross National Happiness Commission, Royal Government of Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2011.

- United Nations Environment Programme, Environmental Indicators South Asia; United Nations Environment Programme: Pathutmhani, Thailand, 2004.

- Australia Agency for International Development. South Asia Regional, India, Maldives and Bhutan Annual Program Performace Report 2011. Available online: http://www.ausaid.gov.au/Publications/Documents/south-asia-appr.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2013).

- United Nations Development Programme, Decentralisation: Bringing Governance Closer to the People; United Nations Development Programme in Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2002.

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. Happiness, Economy, and Institutions. Eco. J. 2000, 110, 918–938. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Foa, R.; Peterson, C.H.; Welzel, C. Development, freedom, and rising happines. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 3, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Hart, M.; Posner, S.; Talberth, J. Beyond GDP: The Need for New Measures of Progress; Boston University: The Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.K.; Fitoussi, J.P. Report of the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Available online: http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/en/index.htm (accessed on 4 June 2013).

- Pickett, K.; Wilkinson, R. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger; Bloomsbury Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T.; Michaelis, L. Policies for Sustainable Consumption; Sustainable Development Commission: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.A.; Vandenberg, M.P. Consumption, Happiness, and Climate Change; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R.A.; McVey, L.A.; Switek, M.; Sawangfa, O.; Zweig, J.S. The happiness-income paradox revisited. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 107, 22463–22468. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, C.; Schwarz, N.; Deiner, E.; Kahneman, D. Zeroing in on the dark side of the American dream: A closer look at the negative consequences of the goal financial success. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 14, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T. The High Price of Materialism; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Offer, A. The Challenge of Affluence: Self-control and Well-being in the United States and Brittain since 1950; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gross National Happiness Commission. Available online: http://www.gnhc.gov.bt/mandate/ (accessed on 27 December 2012).

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social influence: compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S. Learning to live in a global commons: socioeconomic challenges for a sustainable environment. Ecol. Res. 2006, 21, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddoe, R.; Costanza, R.; Farley, J.; Garza, E.; Kent, J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Martinez, L.; McCowen, T.; Murphy, K.; Myers, N.; et al. Overcoming systemic roadblocks to sustainability: the evolutionary redesign of worldviews, institutions, and technologies. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2483–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzig, A.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Alston, L.J.; Arrow, K.; Barrett, S.; Buchman, T.G.; Daily, G.C.; Levin, B.; Levin, S.; Oppenheimer, M.; et al. Social norms and global environmental challenges: the complex interaction of behaviors, values, and policy. Bioscience 2013, 63, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Levin, S. The evolution of norms. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, 943–948. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, R.; Richerson, P.J. The Origin and Evoluiton of Cultures; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D.J.; Hironaka, A.; Schofer, E. The nation-state and the natural environment over the twentieth century. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, R. Toward a Buddhist Environmental Ethic. J. Am. Acad. Relig. 1997, 65, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, D.R. Healing Ecology. J. Buddh. Ethics 2010, 17, 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, K.; Colman, R. Educating for GNH. Proceedings of the Educating for Gross National Happiness Workshop, Thimphu, Bhutan, 7–12 December 2009; Available online: http://www.gpiatlantic.org/pdf/educatingforgnh/educating_for_gnh_proceedings.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2013).

- Kuensel Home Page. Available online: http://www.kuenselonline.com (accessed on 18 June 2013).

- National Environment Commission, The Middle Path: National Environment Strategy for Bhutan; Keen Publishing Co., Ltd.: Bangkok, Thailand, 1998.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Biodiversity Action Plan for Bhutan; Keen Publishing Co. Ltd.: Bangkok, Thailand, 2002.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Biodiversity Action Plan 2009; Royal Government of Bhutan: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2009.

- Inglehart, R. Public support for environmental protection: objective problems and subjective values in 43 societies. Polit. Sci. Politics 1995, 28, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bama Village, Thimphu Dzongkhag. Quote from focus group meeting, 2006

- Tshochekha Village, Thimphu Dzongkhag. Quote from focus group meeting, 2006

- Zanglakha Village, Thimphu Dzongkhag. Quote from focus group meeting, 2006

- Shingnyeer Village, Bumthang Dzongkhag. Quote from focus group meeting, 2006

- New Economics Foundation, The Un-Happy Planet Index 2.0: Why Good Lives Don’t Have to Cost the Earth; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2009.

- Gross National Happiness Commission, Eleventh Round Table Meeting: Turning Vision into Reality: The Development Challenges Confronting Bhutan; Gross National Happiness Commission: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2011.

- Frame, B. Bhutan: A review of its approach to sustainable development. Dev. Pract. 2005, 15, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Bureau; Asian Development Bank. Bhutan Living Standards Survey 2012 Report; Thimphu, Bhutan, 2013.

- Gene and Tsocheckha Villages, Thimphu Dzongkhag. Quote from focus group meeting, 2006

- Ura Doshey Village, Bumthang Dzongkhag. Quote from focus group meeting, 2006

- Gene Village, Thimphu Dzongkhag. Quote from focus group meeting, 2006

- Amiel, M.H.; Godefroy, P.; Lollivier, O. Quality of Life and Well-Being often Go Hand in Hand; National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE): Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Self, A.; Thomas, J.; Randall, C. Measuring National Well-being: Life in the UK in 2012; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2012.

- Kroll, C.; Meditz, H. Scientific Research Survey: “Well-Being of Parents and Children”; Ministry for Family Affairs, SeniorCitizens, Women and Youth: Berlin, Germany, 2009.

- Canadian Index of Wellbeing, How Are Canadians Really Doing? The 2012 CIW Report; Canadian Index of Wellbeing and University of Waterloo: Waterloo, Canada, 2012.

- Don’t worry, be happy. Available online: http://www.economist.com/node/18388884 (accessed on 25 June 2013).

- McDonald, R. Towards a new conceptualization of Gross National Happiness and its foundations. J. Bhutan Stud. 2005, 12, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R. Selling desire and dissatisfaction: Why advertising should be banned from Bhutanese television. In Media and the Public Culture, Proceedings of the Second International Seminar on Bhutan Studies, Thimphu, Bhutan, 2006; Centre for Bhutan Studies: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Government of Bhutan, The Report of the High-Level Meeting on Wellbeing and Happiness: Defining a New Economic Paradigm; The Permanent Mission of the Kingdom of Bhutan to the United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- United Nations General Assembly. Happiness: Towards a holistic approach to development. Available online: http://www.earth.columbia.edu/bhutan-conference2011/sitefiles/UN%20Resolution%20on%20Happiness.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2013).

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Brooks, J.S. Avoiding the Limits to Growth: Gross National Happiness in Bhutan as a Model for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3640-3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5093640

Brooks JS. Avoiding the Limits to Growth: Gross National Happiness in Bhutan as a Model for Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2013; 5(9):3640-3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5093640

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrooks, Jeremy S. 2013. "Avoiding the Limits to Growth: Gross National Happiness in Bhutan as a Model for Sustainable Development" Sustainability 5, no. 9: 3640-3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5093640

APA StyleBrooks, J. S. (2013). Avoiding the Limits to Growth: Gross National Happiness in Bhutan as a Model for Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 5(9), 3640-3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5093640