2.1. Aims and Methods: Case Study Profile

The BAT4MED project analyses the potential impact of the introduction of the IPPC approach in the Mediterranean Partner Countries (MPC) and, more specifically, if and how this can contribute to minimizing the negative impacts associated with the activities from key industrial sectors in the MPC in order to ensure a higher level of environmental protection in the region.

The project aims to help implement the EU Technologies Action Plan by supporting the transfer and uptake of environmental technologies in developing countries. To that aim, the possibilities for and impact of diffusion of the EU IPPC approach to the MPC will be assessed and the implementation of BAT in the national environmental programs will be promoted and supported.

Specific objectives of the project are as follows:

- –

To identify, assess and select the BAT for pollution prevention and control in key industrial sectors with the highest environmental potential benefit;

- –

To promote and spread the use of BAT through dissemination activities;

- –

To assess the possibility and the impact of disseminating the EU IPPC approach to the MPC;

- –

To achieve these objectives, the project relies on a concise working methodology and structure.

Firstly, the BAT4MED project analyzed the industrial context in the MPC to select the most promising sectors with the highest environmental benefit potential. This preliminary analysis includes a benchmarking exercise of national analysis reports that identify possible synergies and selects those sectors that can ensure the highest global impact in the region for further study. Through an in-depth analysis of the potential transferability of results, the two most promising industrial sectors with the highest environmental potential benefit selected were the textile sector and the food sector, specifically, the dairy sector. Though the industrial and economic situation may vary notably between the different MPCs, the analysis carried out reveals that most of the problems faced by the Mediterranean industries are common to the majority of countries, which will be the key to spread results and ensure their transferability.

Secondly, a methodology for the assessment of available environmentally friendly techniques, so-called candidate BAT, and the selection of BAT was developed. For each target sector, the BAT were selected accordingly, taking into account specific sector and local conditions in the participating MPC. The methodology assesses the candidate BAT at a sector level, with respect to their technical and economic viability and environmental benefit.

The methodology was used to assist the MPCs and the technical working groups (TWGs) in drafting national BAT sector reports. It provides not only a clear and transparent evaluation tool for candidate BAT, but also guidelines on the elaboration of BAT sector reports, e.g., it indicates that the data needs to be used to conduct a BAT analysis. In the future, the methodology will inevitable provide support to policy makers and permit writers, in general, in the selection of BAT.

During the process of writing the methodology and elaborating the BAT sector reports, an Expert Group (EG)—consisting of key experts in the field of IPPC at the European level—was called upon to help guarantee the scientific and technical quality of the project’s outcomes. This part of the project is further discussed in paragraph 2.2 on the elaboration of the national BAT sector reports.

Additionally, an analysis of the potential convergence of MPC policies with the EU approach is carried out in order to assess the potential for the future adaptation of the existing MPC, permitting procedures to integrate principles based on the IPPC approach. This stage aims at analyzing and benchmarking policy and legislative frameworks regarding IPPC in the MPC. In particular, the methodological approach for the analysis will help the MPC to collect the information and to ensure the comparability of project results in order to assess the possibility and the impact of diffusing the EU IPPC approach to the MPC and other Mediterranean countries. In addition, the conclusions of this analysis will provide policy recommendations to support the implementation of BAT in the MPC.

Though BAT4MED is tackled from the perspective of the two particular industrial sectors selected (textile and dairy), all tools and methodologies have been designed and implemented in a universal way, allowing the replication of the whole project in other countries and industrial sectors. To this end, particular efforts have been put into the development of each methodology, to ensure its applicability within the context of the project, but also beyond it.

2.2. Elaboration of National BAT Sector Reports.

The primary objective of determining BAT at a sector level is to provide support to policy makers and permit writers. For the elaboration of a BAT report, both a procedure on how to tackle this type of study, as well as a methodology for BAT evaluation is required. Since the concept of BAT and its application in a regulatory framework is mostly known and used in Europe, it is important to perform a consistency check with the situation and practices in the MPCs. A translation of the methods known and applied in Europe is therefore needed.

Generally, when performing a BAT evaluation, expert involvement is of high importance. Therefore, a sector technical working group (TWG) is called together on a regular basis. This TWG should consist of representatives from the sector (from companies or sector associations), public agencies and independent experts. All parties involved should preferably be represented in order for the results to be widely supported. The role of the TWG is to assist in the data collection and to present their view on the criteria to be evaluated in selecting the BAT. In total, three TWG meetings were organized in the course of the BAT4MED project, each focusing on specific parts of the BAT evaluation.

In the first phase of a BAT study, information collection is the focus point. In order to get a clear description and positioning of the sector for what economics and regulations are concerned, different types of information and data are gathered: general sector information, sector-related national and international legislation and sector-specific economic data. The general and economic information on the sector concerns mostly number and size of companies, yearly turnover values and other financial ratios. These data are grouped to assess the financial strength of the sector as a whole. Data on the number and type of suppliers, on the number and type of customers, on the threat of substitute products, the attractiveness of the market for new enterprises and on international competition are obtained, to be gathered in a Porter’s Five Forces evaluation to assess the competitiveness of the companies in the sector. All this information can be retrieved either from statistical agencies or reporting (similar to Europe) and/or from sector experts. Legislative information is, then again, mainly gathered from official agencies and is needed to clearly describe the framework in which the sector operates.

In order to come to a selection of BAT, first a list of candidate BAT must be compiled. Candidate BAT are all techniques with potential environmental advantages. Candidate BAT are found in the literature (BREFs, research articles…), observed during plant visits or proposed by sector experts. For each candidate BAT, a number of aspects are to be studied, such as the achieved environmental benefits, cross-media effects, the economics and example plants. More information on the necessary information can be found in the guidance document (2012/119/EU). There is an important role for the TWG in gathering this information, i.e., to clearly indicate the specific local conditions. These local issues, e.g., very low price of water and electricity, might have a decisive influence on the evaluation of candidate BAT.

To evaluate the candidate BAT, a stepwise methodology is followed. In the first step, the technical viability of the candidate BAT is evaluated. A good indicator for the technical viability is the application in the sector or under conditions that are considered relevant for the sector as a whole. A technique only tested on an experimental scale is, in principle, not technically viable. The technique may, when properly applying the appropriate security measures, not lead to an increased risk of fire, explosions or accidents in general and may not influence the quality of the end product. Secondly, the environmental performance of the candidate BAT is evaluated, either qualitatively or quantitatively. Finally, the economic viability (cost feasibility and effectiveness) of the candidate BAT is evaluated. A quantitative approach can supplement or replace a qualitative approach, but is highly dependent on the availability of data on investment and operational costs of the candidate BAT and the environmental effects/benefits. Based on the scoring of these three criteria, the BAT are selected. When only limited data are available and a solely qualitative approach is followed, conclusions are especially subjected to the expert judgment of the TWG members.

2.2.1. Dairy BAT Reports

The dairy sector in the three MPCs is characterized by a large number of very small dairy producers that produce their products in an artisan way. Besides these micro-, traditional dairy processing companies, there are mostly SME’s (Small and Medium Enterprises) and only a few large companies (on average > 150 employees). Companies above the IPPC size threshold (quantity of milk received daily is >200 tones, average on an annual basis) are rather rare or even nonexistent. In Egypt, for example, the dairy sector is quite important. It is responsible for about 15.9% of total manpower in Egypt and 9% of all production facilities. In Tunisia, the dairy sector has a strategic role in the food industry. It is responsible for about 8% of production volume and 5% of investments.

The scope of the BAT evaluation includes the production of all dairy products. Only for Tunisia, cheese and milk powder production are not included in the evaluation, due to the lack of data.

The TWGs in each MPCs were composed, taking the importance of diversity in members into account (see the previous section on methodology). For Morocco and Tunisia, this led to a TWG with an almost equal presence of sector representatives (companies, sector federations), independent experts (consultants and university professors) and public administration representatives. For Egypt, however, this was not the case. Only independent experts and one representative of a public administration constituted the TWG.

As was mentioned, data on the competitiveness, investments, turnover, employees, etc., forms an important basis in order to get a clear picture of the sector’s financial strength and resilience. This type of information was, however, quite hard to gather, especially when the data had a confidential character. Some information on the financials of companies in the dairy sector was provided in Egypt and Tunisia. However, these data were rather outdated. Expert judgment remained necessary to evaluate the relevance of these numbers. For Morocco, only very limited information was available. Overall, it was clear that this type of information is not reported as transparently as it is done in Europe. The confidential aspect towards competitors is the main obstacle. As far as the legislative framework in the MPCs is concerned, it is clear that this is quite different from the European legislative framework in the sense that emission limit values are general, no sector specific approach is applied and, in many cases, implementation of the legislation and control on compliance is inadequate and, therefore, often ineffective.

The candidate BAT were listed based on the European BAT reference document (BREF), Food, Drink and Milk, the Flemish BAT study for the dairy sector [

27] and input from the TWG members in the different MPCs. A list of, respectively, 56, 55 and 56 candidate BAT for the dairy sector in Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco was compiled (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of (candidate) Best Available Techniques (BAT) per Mediterranean Partner Countries (MPC) for dairy sector.

Table 1.

Number of (candidate) Best Available Techniques (BAT) per Mediterranean Partner Countries (MPC) for dairy sector.

| MPC | Candidate BAT | BAT | Conditional BAT | No BAT |

|---|

| Egypt | 56 | 48 | 6 | 2 |

| Tunisia | 55 | 46 | 8 | 1 |

| Morocco | 56 | 47 | 8 | 1 |

The techniques focus on the use of water and energy, the emission (discharge) of waste water and the generation of waste, plus a number of general techniques that are related to the plant level instead of the process level.

Although for each of these techniques, quite a bit of information is already available in the literature, specific information related to the circumstances in the MPCs is important in evaluating the techniques and selecting the BAT. Therefore, the TWG members were asked to provide data on the applicability, the environmental performance, economics (investment and operational costs), driving forces for implementation and example plants in the MPCs. Especially, qualitative aspects were known and made available in the course of the study. Quantitative information on environmental performance and the economics was hardly ever provided or even available to the TWG members.

The information provided by the TWG members on local issues was considered of great importance for the final results of the study. When evaluating the candidate BAT for dairy in the different MPCs, most of the techniques, however, were equally considered BAT or not, independent of the country. For some techniques, the information on local issues did in fact make a difference towards the final conclusions. For example, the use of self-neutralization to reduce the amount of waste water was considered BAT under certain conditions in Morocco, but was not considered BAT in Tunisia. This is due to the fact that the technique is not considered applicable in Tunisia today. No installations have the required pH variation for the technique to properly work. In Morocco, however, there are installations that can apply the technique, and therefore, it is considered BAT. Another example is the use of CHP (combined heat and power). In Egypt, current fuel prices make it hardly impossible for CHP to be economically viable for dairy companies, while in Tunisia, this is currently not the case. Of course, factors, such as fuel prices, vary over time and can make a difference in conclusions when changes occur. This, again, stresses the added value of quantitative information in a BAT evaluation. Economic viability can be evaluated more objectively and price fluctuations can be taken into account to determine the robustness of the BAT conclusion.

Due to the lack of quantitative data, several aspects of a typical BAT study could not be elaborated in detail in the reports. A good example is the final stage of the BAT studies as made in Europe: the setting of BAT-associated emission levels (BAT AELs). In order to make this possible, a clear picture of the environmental performance of the companies and the techniques is necessary. The BAT analysis eventually indicated 54 (Egypt and Tunisia) and 55 techniques (Morocco) to be BAT, however, with a number of techniques being limited in applicability or through economic viability (

Table 1).

For example, BAT to minimize waste water in the Egyptian dairy industry is to apply one or a combination of the following four techniques:

- –

Minimizing the use of EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid)

- –

Provision and use of catchpots over floor drains

- –

Minimize the blowdown of a boiler

- –

Maximize condensate return

Same account for the Moroccan and Tunisian dairy industry.

Overall, the BAT considered as a priority in Egypt were mainly good management practices (e.g., repair leaking valves), monitoring and control (e.g., of water) and energy conservation. For Tunisia, the priorities are mainly the reduction of water and energy consumption and raising good environmental practices to be implemented. The main focus there lies with the preventative measures due to cost constraints. In Morocco, the TWG members indicate good housekeeping, monitoring of water and energy consumption and training and awareness of employees to be top priority.

2.2.2. Textile BAT Reports

In Egypt, the textile and clothing industry plays a crucial role in the economic, social and political context of the country. In particular, the cotton sub-sector is very important in the economy, also for export. The textile and clothing sectors include 4,500 companies and employ around 700,000 direct workers. If indirect employment is considered, that number increases to over one million. In Egypt, there is still a strong presence of public textile companies. There are around 27, and they employ around 100,000 workers. The main textile products are apparel fabrics, terry towels, bed linen, furnishing fabrics, industrial/technical fabrics and non-woven fabrics. Furthermore, in Morocco, the textile sector is one of the most important ones. It plays a strategic role for the Moroccan economy. There are about 200,000 employees, corresponding to 40% of the national industrial employment. Despite a difficult world economic crisis, in 2012 and 2011, the textile exports of Morocco to European countries grew. In Tunisia, the textile sector is the largest one in the country in terms of exports, employment and added value. There are about 2,000 textile companies (with about 10 employees for each); most of them are small and medium enterprises. About 85% of the Tunisian textile companies are producing only for export. Most firms receive foreign direct investments: French companies are the leading foreign investors in the textile and clothing sector in Tunisia, followed by Italian companies.

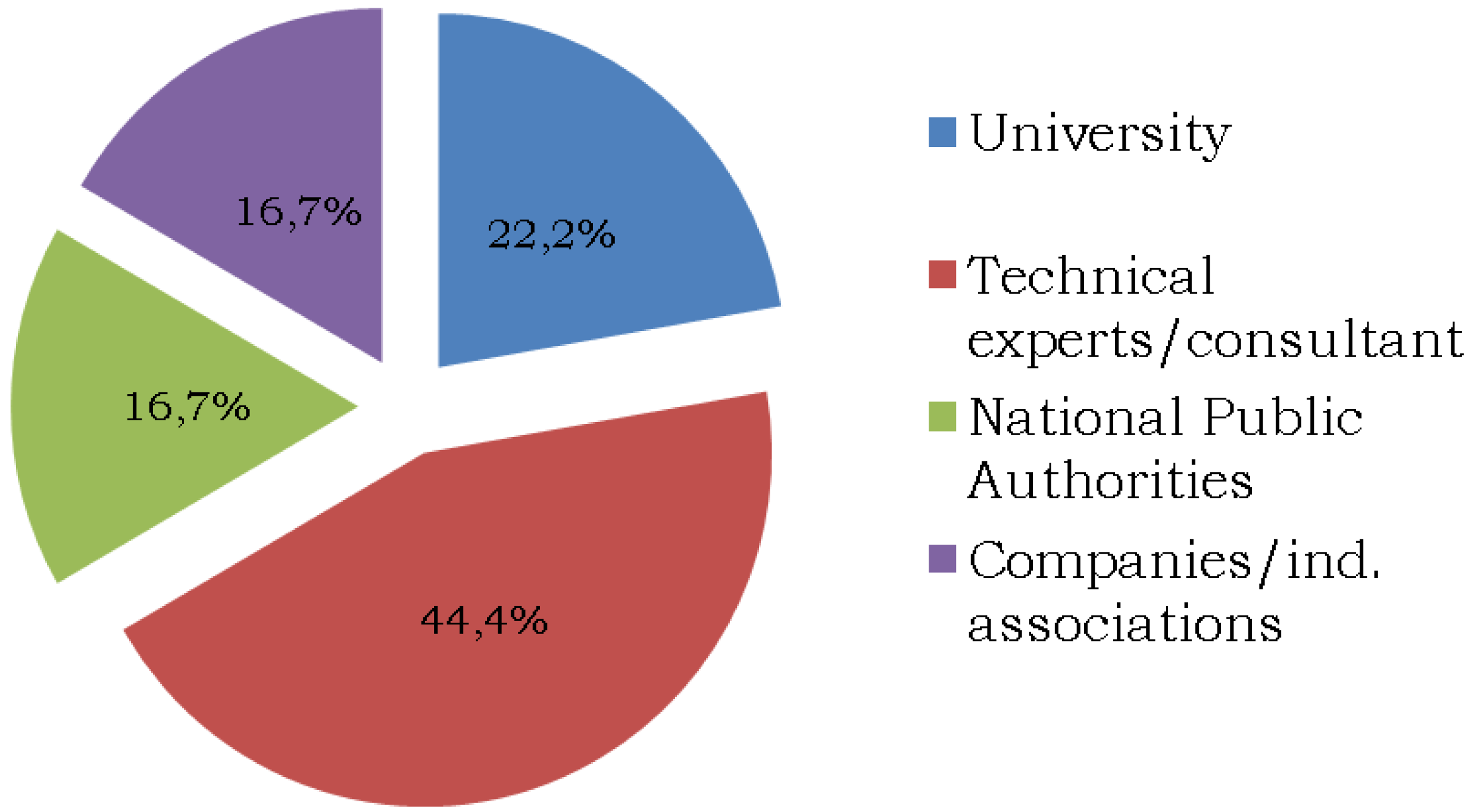

As described in the previous section, to support the selection of BAT and the elaboration of the reports, a key contribution was made by TWG members. The elaboration of reports aimed to valorize skills and knowledge on textile processes and characteristics of the TWG members and to include them in these documents. In

Figure 1, the representativeness of economic and public categories of TWG members is given.

Figure 1.

Technical working groups (TWGs) members for representative categories (for the three countries).

Figure 1.

Technical working groups (TWGs) members for representative categories (for the three countries).

For each of the three MPCs, some specific processes to which the BAT reports focus were selected. The selection was justified by two main reasons: the high environmental relevance of these processes and the large number of companies in each of the three countries that are focused on them. For Egypt, it was decided to focus on all processes for the production of cotton textile products. In particular, techniques belonging to pre-treatment, dyeing, printing, washing, drying, finishing, coating and laminating processes were included in the BAT report. In the case of Morocco, the processes considered were focused on pre-treatment and dyeing. They included all kind of fibers, such as cotton and other natural, artificial and synthetic fibers. Since wool is not a key fiber in the textile processes in Morocco, techniques referred to wool were excluded from the BAT report. In the BAT report of Tunisia, dyeing and finishing processes were considered.

In order to identify the candidate BAT, partners collected information about techniques through the consultation of a wide number of sources. Candidate BAT included in the BAT reports consist in both vertical techniques (e.g., techniques that can be applied only to textile sector) and horizontal techniques (e.g., techniques that can be applied to all IPPC sectors and also to the textile one). In the case of vertical candidate BATs, first of all, partners of the project consulted the European Best Reference Document (BREF) for the textile sector, (EC, 2003). Considering that the issuing date of the current version of BREF is the year 2003, partners know that the main challenge in this sense was to check other sources, where they can find results of recent researches on textile techniques. For this reason, other important considered sources were, for example, the Flemish BAT report for the textile sector (Flemish Institute for Technological Research, VITO, translated version, 2011); pollution prevention in the textile sector within the Mediterranean Region (Regional Activity Centre for Cleaner Production, CPRAC, 2002); technical reports of EU-funded projects on the textile sector (e.g., Funded through Life Programme); and many scientific and academic articles about technologies and techniques adopted and/or experimented upon in the textile sector.

The candidate BATs that were identified were classified according to specific classes and subclasses. For example, one of the identified classes is “end of pipe techniques” for abatement pollution techniques. Under this class, some subclasses were created (e.g., wastewater or air emissions abatement techniques), grouping the identified techniques through sources consultation. In total, for the textile sector, about 90 vertical candidate BATs were identified in the project.

One of the end of pipe techniques identified through a scientific article was named “removal of disperse dyes from textile wastewater using bio sludge”. The technique is characterized by the high adsorption capacity of bio sludge on dyes and organic matter in wastewater, allowing the reduction of some polluting parameters and dyes in wastewater.

All identified candidate BATs have been assessed according to the methodology elaborated earlier on in the project. A key aspect about the evaluation and the assessment of candidate BAT was the bottom-up approach; BAT were identified “on the field”, paying attention to local issues and aspects referring to specific conditions and characteristics of each MPC. A sample of textile installations was audited for each of the three countries. Two of the candidate BAT were identified internally to industrial processes of audited companies. One of these two candidate BAT was named “dry bleaching using ozone instead of wet washing using chlorine or hydrogen peroxide”. It consists of placing garments in a dry rotary washing machine (that is connected to an ozone generator). The technique is used, for example, to bleach the fabric lightly using ozone instead of wet washing using chlorine (or hydrogen peroxide). This technique does not imply the use of water and chemicals.

Moreover, also, the involvement and the active participation of TWG members guarantee the consideration of local aspects.

The results are presented on the following (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of (candidate) BAT per MPC for the textile sector.

Table 2.

Number of (candidate) BAT per MPC for the textile sector.

| MPC | Candidate BAT | BAT | Conditional BAT | No BAT |

|---|

| Egypt | 60 | 32 | 15 | 13 |

| Tunisia | 51 | 26 | 15 | 10 |

| Morocco | 59 | 32 | 9 | 18 |

The main reasons for which candidate BAT resulted as no BAT are linked with them being not economically or technically viable. In the first case, often, techniques require high investments or additional costs compared to the traditionally used methods, and the payback period related to the savings achievable was not always acceptable. In the second case, a negative assessment of technical viability criteria was related to the fact that some techniques (especially the ones collected from scientific articles) are not yet proven on an industrial scale, but only on a pilot scale. For this reason, this group of techniques can be considered as emerging techniques.

The identified BAT were related mainly to the main important environmental aspects for the textile industry: water consumption and water emissions. To improve water emissions, the techniques involve mainly the substitution of chemicals prioritizing preventive measures instead of end of pipe actions. The identification of BAT related to the substitution of chemical with other more environmental friendly techniques was also one of the topics requested by the textile companies that were involved. Many North-African companies are suppliers of European firms, and there has been increasing attention by the consumer on the health issues linked to textile products.

2.2.3. Discussion on the BAT Sector Reports

When elaborating a BAT sector study, data availability is always a key factor. This is true for Europe when elaborating a BREF, but the same can be concluded when transferring the approach to non-EU countries.

The experiences when drawing up the BAT sector reports shows that data availability, especially quantitative data, on all the aspects involved (financial data on the sector, environmental performance data, investment and operational cost data on techniques, etc.) was hard to come by. This, of course, greatly affects the results and the quality of the results.

When quantitative information on the financial strength and resilience of the sector is missing, it is hard to verify the economic viability of techniques. Of course, to do this, investment and cost information on the different candidate BAT is needed, as well. For most of the candidate BAT in the studies, information from the EU BREFs was used: no specific data were available for the supply of the techniques in the MPC markets. Data on the environmental performance of the sector is of great importance, since this creates the opportunity to identify the reduction potential and cost-effectiveness of the candidate BAT. Furthermore, when the BAT environmental reduction potential is known, BAT AELs can be determined. In the reports now, due to the lack of this type of information, no BAT AELs were determined.

During this phase of the project, the involvement of the TWG members was an important success factor. Although not each TWG had the perfect composition, this was not necessarily problematic for the outcome of the project. Since the principle of BAT and, therefore, the principle and role of a TWG is new in the MPCs, this first experience did indicate how environmental issues are valued amongst the people involved. A clear push towards more environmental awareness in industrial sectors was experienced.

An important factor when trying to raise environmental awareness and involvement in industrial sectors, still, is legislation. Each of the MPCs involved indicated that today, that their environmental legislation is a general one, not making any distinction between different activities when setting Emission Limit Values (ELVs). Besides this aspect, environmental permitting is tackled in a totally different way than is done in Europe. It is clear to say that the legislative approach is thus very different from the IPPC approach that we are trying to transfer to the BAT4MED project. The lack of monitoring and obligated reporting make it very hard to facilitate BAT evaluations: the lack of data is inevitable when monitoring is absent. Monitoring can be seen as one key element when trying to implement the IPPC approach: no monitoring means no available data and, therefore, no possibility to state BAT AELs and set ELVs. No monitoring (and reporting) also means that compliance with stated ELVs is very hard to check and, thus, legislation risks being ineffective.

From the experience of the authors, it is clear that there is still a significant legislative gap to be overcome before the IPPC approach and BAT principle can be transferred for real to the MPCs. In order to determine the real potential for future adaptation of the existing MPC legislative procedures and to permit the integration of the principles based on the IPPC approach, the project included an analysis on this matter.