Conservation in Context: A Comparison of Conservation Perspectives in a Mexican Protected Area

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Case and Methods

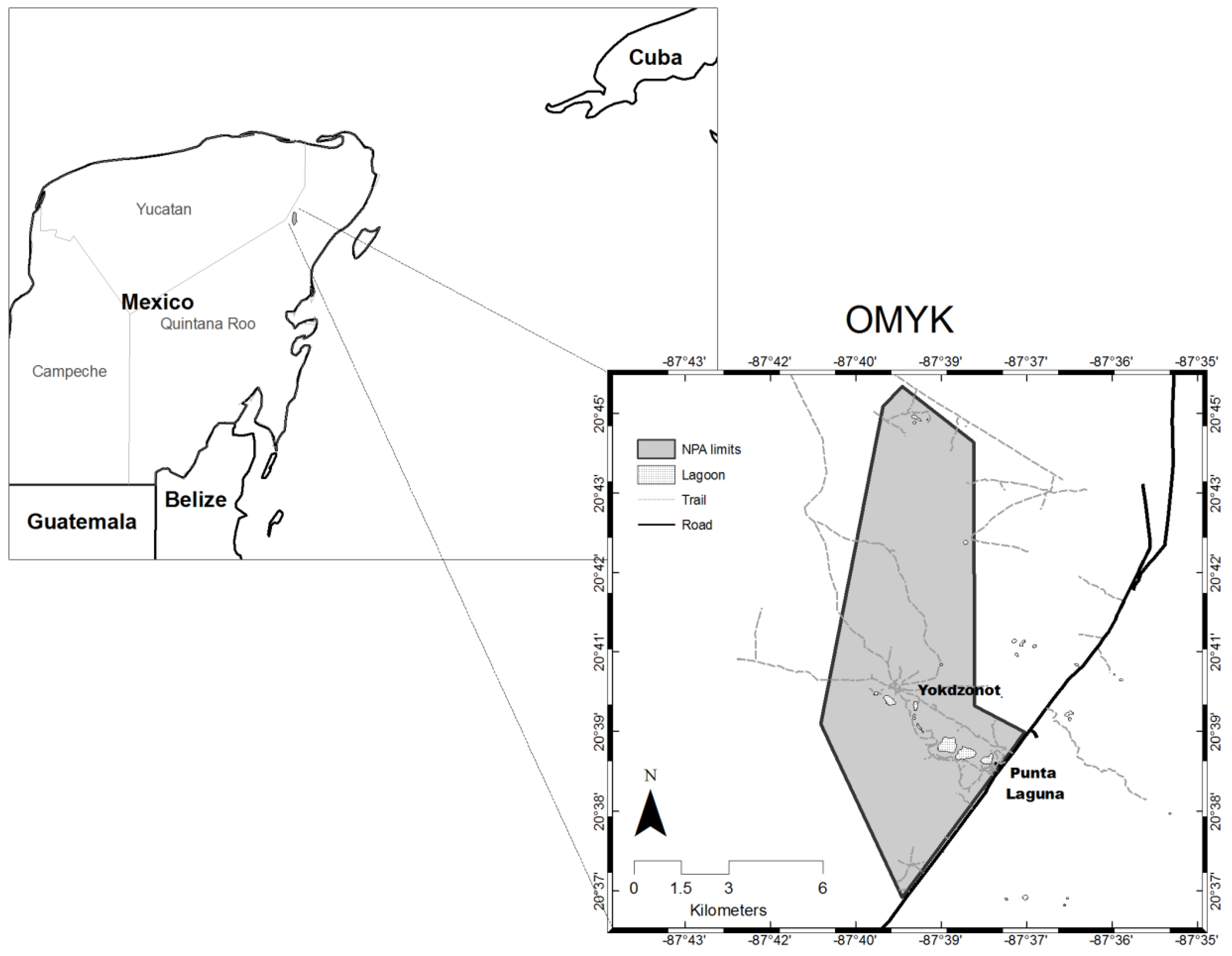

2.1. Study Case: The Social Context of the Otoch Ma’ax Yetel Kooh Protected Area

2.2. Stakeholder Selection

- • Government Agency (GA)—The GA was represented by the CONANP regional office, which supervises all the reserves within the Yucatan Peninsula (Campeche, Quintana Roo, and Yucatan). The CONANP is the agency in charge of the reserves’ management at the local, state, and federal levels, it is responsible for designing and detailing the management plans. In 2005, García-Frapolli interviewed CONANP local staff and reported that the agency originally did not have any interest in designating OMYK as a federal PA because the area did not represent a large regional extension (only 0.4% of the total land protected in the Yucatan Peninsula) [37]. In fact, a field technician was assigned after three years following the PA designation; however since then, the CONANP has had continued presence in the area. Interviews were conducted with all the staff involved in OMYK’s management.

- • Local People (LP)—The LP were represented by individuals living or conducting activities within the OMYK boundaries. All local people were Yucatec Mayas and their activities were based on two broad categories: 1) individuals employed as tourist guides or field assistants for scientific research, and 2) individuals whose livelihoods depended on traditional subsistence activities. At the time of the interviews, some local residents had combined these activities with alternative projects generated by CONANP, such as honey production and queen bee commercialization, road clearing, or handcrafts, all serving as opportunities to generate additional income. All respondents were key representatives of the two communities settled in the PA (Punta Laguna and Yokdzonot).

- • Scientific Researchers (SR)—The SRs were represented by a group of researchers conducting primatologist studies in the reserve. This group had been present in the area for at least a decade previous to its designation as a PA. Respondents included two professors with long-term projects in the area and three graduate students who spend long periods in the field conducting research. These respondents covered the majority of representatives within this group.

- • Non-Governmental Organization (NGO)—This group was represented by Pronatura-Peninsula de Yucatan (PPY), the main organization working with communities residing within the PA limits. According to previous interviews with PPY members [36], the agency’s primary goal was to conserve local biodiversity and promote local development. In addition, the NGO also facilitated the interaction between local communities and other stakeholders. As in the case of the GA, respondents in this group included all the representatives involved with the reserve at various levels.

- • Tourist agencies (TA)—TAs are a growing business in the region and represent an important component of regional economy. TAs do not have direct influence on the management or conservation of resources; however, they provide local economic opportunities, which indirectly influence the use of resources. LP have worked with several TAs over the years, and by the end of the study period the community had signed an agreement with one of the most important TA in the region. According to their web page, the mission of the agency is “to provide tourists with amazing and unforgettable experiences through our natural-cultural and adventure expeditions”, and “to be distinguished internationally as both the best alternative for adventure expeditions […], and an example of sustainable recreational tourism” [44]. The only respondent of this group was the regional manager.

| Group | Role | Activity | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government Agency (GA) | Regional director | In charge of supervising all the PAs in the Yucatan Peninsula. | 1 |

| Reserve director | In charge of the management of the PA. | 1 | |

| Field technician | In charge of field projects. | 1 | |

| Local People (LP) | Yokdzonot | Community living far from roads. They still rely on slash and burn agriculture as their main subsistence activity. The four respondents all represent working men from the community. | 4 |

| Punta Laguna | Community living next to the main road. The community is transitioning from subsistence to economic activities where they work on tourist-related activities or as “field assistants” for scientific studies. One of the respondents was the president of the cooperative, who is in charge of administrating revenues from tourism. The other respondent was the representative for local tourist guides. | 2 | |

| Scientific Researches (SR) | Principal researchers | Have long-term projects in the area. They started working in the area in the late 1990s. | 2 |

| Graduate students | Spend long periods of time (> one year) in the field carrying out their research. | 3 | |

| Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) | Executive director | In charge of supervising all the projects the NGO has in the Yucatan Peninsula. | 1 |

| Advisor | Involved with the NGO and the PA for over a decade. The advisor has to coordinate alternative projects, with particular emphasis to those targeting women, and advises the board committee regarding communities in the PA. | 1 | |

| Projects assistants | In charge of field projects in two communities. | 2 | |

| Tourist Agency (TA) | Regional coordinator | Supervises the regional agency activities. Is in charge of tour crews and negotiations with local people. | 1 |

| 19 | |||

2.3. Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Priority Goals

| Most important goal | % |

|---|---|

| Improve local livelihoods | 89.5 |

| Conserve biodiversity | 84.2 |

| Promote regional development | 42.1 |

| Preserve cultural traditions | 21.0 |

| Use and extraction of nat. resources | 15.8 |

| Scientific research | 15.8 |

| Goal | Goal equivalent in the management plan | Government (3) | Local (6) | Researchers (5) | NGO (4) | Tourist Agency (1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biodiversity Conservation | 1) Protect, conserve, and recover the natural environment, and maintain the equilibrium and continuity of ecological processes through the appropriate management and sustainable use of natural resources, including the participation of all relevant actors.; 2) Conserve the diversity and integrity of ecosystems, species, and germplasm, as well as the ecological processes associated with them. | 100 | 100 | 60 | 100 | 0 | |

| Preserve cultural traditions | Conserve and protect cultural, archeological, and historical heritage, protecting the landscape and scenery beauty. | 0 | 17 | 20 | 50 | 0 | |

| Scientific Research | Promote scientific research important for the use and protection of important species; assist environmental and social issues, and provide elements for the monitoring and evaluation of the use of natural resources. | 0 | 33 | 0 | 25 | 0 | |

| Improvement of local livelihoods | Promote the development of sustainable activities based on scientific information, improve local activities, and as consequence, improve the quality of life of local communities. | 67 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 100 | |

| Recover and restore endangered or deteriorated areas important for local species and ecosystems. | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

3.2. Forest Conservation: Challenges and Opportunities

3.3. Local Wellbeing: Challenges and Opportunities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Weber, R.; Butler, J.; Larson, P. Indigenous People and Conservation Organizations: Experiences in Collaboration; World Wildlife Fund (USA): Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Guha, R.; Martinez-Alier, J. Varieties of Environmentalism; Earthscan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, A.G.; Gullison, R.E.; Rice, R.E.; Fonseca, G.A.B.d. Effectiveness of parks in protecting tropical biodiversity. Science 2001, 291, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.; Sanchez-Cordero, V. Effectiveness of natural protected areas to prevent land use and land cover change in Mexico. Biodiv. Conserv. 2008, 17, 3223–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J.M.; Adams, W.M.; Murombedzi, J.C. Back to the barriers? Changing narratives in biodiversity conservation. Forum Dev. Stud. 2005, 2, 341–370. [Google Scholar]

- Young, E. Local people and conservation in Mexico’s El Vizcaino biosphere reserve. Geogr. Rev. 1999, 89, 364–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Rethinking community-based conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Cuesta, R.M.; Martínez-Vilalta, J. Effectiveness of protected areas in mitigating fire within their boundaries: Case study of Chiapas, Mexico. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter-Bolland, L.; Ellis, E.A.; Guariguata, M.R.; Ruiz-Mallen, I.; Negrete-Yankelevich, S.; Reyes-Garcia, V. Community managed forests and forest protected areas: An assessment of their conservation effectiveness across the tropics. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2012, 268, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, M. A challenge to conservationists. World Watch 2004, 17, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Waltner-Toews, D.; Kay, J.J.; Neudoerffer, C.; Gitau, T. Perspective changes everything: Managing ecosystems from the inside out. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Peralvo, M. Coupling community heterogeneity and perceptions of conservation in rural South Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 38, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, L.; Lazos, E. The local perception of tropical deforestation and its relation to conservation policies in Los Tuxtlas biosphere reserve, Mexico. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.E. The role of science in ngo mediated conservation: Insights from a biodiversity hotspots in Mexico. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2006, 9, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenn, N. The power of environmental knowledge: Ethnoecology and environmental conflicts in mexican conservation. Human Ecology 1999, 27, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Contreras, J.; Dickinson, F.; Castillo-Burguete, T. Community member viewpoints on the Ría Celestún biosphere reserve, Yucatan, Mexico: Suggestions for improving the community/natural protected area relationship. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujadas, A.; Castillo, A. Social participation in conservation efforts: A case study of a biosphere reserve on private lands in Mexico. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 20, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H. Local and extra-local perceptions of national parks and protected areas. Landsc. Urban Plann. 1986, 13, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lele, S.; Wilshusen, P.; Brockington, D.; Seidler, R.; Bawa, K. Beyond exclusion: Alternative approaches to biodiversity conservation in the developing tropics. Curr. Opinion Environ. Sust. 2010, 2, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFries, R.; Hansen, A.; Turner, B.L.; Redi, R.; Liu, J. Land use change around protected areas: Management to balance human needs and ecological function. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannigel, E. Integrating parks and people: How does participation work in protected area management? Soc. Nat. Resour. 2008, 21, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Espinosa de los Monteros, R. Evaluating ecotourism in natural protected areas of La Paz Bay, Baja California Sur, México: Ecotourism or nature-based tourism? Biodi. Conserv. 2002, 11, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boege, E. El Patrimonio Biocultural de los Pueblos Indígenas de México: Hacia la Conservación in situde la Biodiversidad y Agrodiversidad en los Territorios Indígenas; INAH: Mexico City, Mexico, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smardon, R.C.; Faust, B.B. Introduction: International policy in the biosphere reserves of Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2006, 74, 160–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A. Ecological information system: Analyzing the communication and utilization of scientific information in Mexico. Environ. Manag. 2000, 25, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiallo, E.A.; Jacobson, S.K. Local communities and protected areas: Attitudes of rural residents towards conservation and Machalilla national park, Ecuador. Environ. Conserv. 1995, 22, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeroy, R.; Parks, J.; Watson, L. How is your MPA Doing?: A Guidebook of Natural and Social Indicators for Evaluating Marine Protected Area Management Effectiveness; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, T.D.; Sarukhán, J. Árboles Tropicales de México: Manual para la Identificación de las Principales Especies, 3rd ed; UNAM,FCE: Mexico City, Mexico, 2005; p. 523. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla Moheno, M. Forest recovery and management options in the Yucatan peninsula, Mexico. PhD Dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Fernandez, G. Vocal communication in a fission-fusion society: Do spider monkeys stay in touch with close associates? Int. J. Primatol. 2005, 26, 1077–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fernandez, G.; Pinacho-Guendulain, B.; Miranda-Perez, A.; Boyer, D. No evidence of coordination between different subgroups in the fission-fusion society of spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi). Int. J. Primatol. 2011, 32, 1367–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fernandez, G.; Boyer, D.; Aureli, F.; Vick, L.G. Association networks in spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2009, 63, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fernandez, G.; Vick, L.G.; Aureli, F.; Schaffner, C.; Taub, D.M. Use of secondary forest by spider monkeys. Folia Primatol. 2004, 75, 406–407. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Frapolli, E.; Ayala-Orozco, B.; Bonilla-Moheno, M.; Espadas-Manrique, C.; Ramos-Fernandez, G. Biodiversity conservation, traditional agriculture and ecotourism: Land cover/land use change projections for a natural protected area in the northeastern Yucatan peninsula, Mexico. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2007, 83, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Frapolli, E. Conservation from Below: Socioecological Systems in Natural Protected Areas of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- García-Frapolli, E.; Ramos-Fernández, G.; Galicia, E.; Serrano, A. The complex reality of biodiversity conservation through natural protected area policy: Three cases from the Yucatan peninsula, Mexico. Land Use Pol. 2009, 26, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Frapolli, E.; Toledo, V.M.; Martinez-Alier, J. Adaptations of a Yucatec Maya multiple-use ecological management strategy to ecotourism. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Fernandez, G.; Ayala-Orozco, B.; Bonilla-Moheno, M.; García-Frapolli, E. Conservacion Comunitaria en Punta Laguna: Fortalecimiento de Instituciones Locales para el Desarrollo Sostenible. In Memorias 1er. Congreso Internacional de Casos Exitosos de Desarrollo Sostenible del Tropico, Boca del Río, Veracruz, Mexico, 2005; Universidad Veracruzana, Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales: Boca del Río, Veracruz, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Moheno, M. Damage and recovery of forest structure and composition after two subsequent hurricanes in the yucatan peninsula. Caribb. J. Sci. 2012, 46, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Moheno, M.; Holl, K.D. Direct seeding to restore mature-forest species in areas of slash and burn agriculture. Restor. Ecol. 2010, 18, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONANP, Programa de Manejo-Area de Protección de Flora y Fauna Otoch Ma'ax Yetel Kooh; SEMARNAT: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006; p. 149.

- García-Frapolli, E. Exclusión en áreas naturales protegidas: Una aproximación desde los planes de manejo. In La Naturaleza en Contexto: Hacia una Ecología Política Mexicana; Durand, L., Figueroa, F., Guzmán, M., Eds.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Méxic: Mexico City, Mexico, in press.

- Alltournative. Who we are? Available online: http://www.alltournative.com/who-we-are/mission-and-vision.asp (accessed on 28 June 2012).

- Axford, J.C.; Hockings, M.T.; Carter, R.W. What constitutes success in pacific island community conserved areas? Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Gossling, S. Ecotourism: A means to safeguard biodiversity and ecosystem functions? Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Ecotourism and economic incentives-An empirical approach. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmford, A.; Beresford, J.; Green, J.; Naidoo, R.; Walpole, M.; Manica, A. A global perspective on trends in nature-based tourism. PLoS Biology 2009, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, O. The role of ecotourism in conservation: Panacea or pandora’s box? Biodiv. Conserv. 2005, 14, 579–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONANP, Programa Nacional de Areas Naturales Protegidas (2007-2012). Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas; SEMARNAT/CONANP: Mexico, Mexico City, 2007; p. 50.

- La Jornada. Apoyarán turismo en áreas naturales protegidas. La Jornada, 4 June 2007.

- Bruyere, B.L.; Beh, A.W.; Lelengula, G. Differences in perceptions of communication, tourism benefits, and management issues in a protected area of rural Kenya. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.; Wall, G. Ecotourism and community development: Case studies from Hainan, China. Environ. Manag. 2004, 33, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A. Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tourism Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, B.B. Maya environmental successes and failures in the yucatan peninsula. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2001, 4, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, B.B.; Bilsborrow, R. Maya culture, population, and the environment on the Yucatán peninsula. In Population, Development, and Environment on the Yucatán Peninsula: From Ancient Maya to 2030; Lutz, W., Prieto, L., Sanderson, W., Eds.; International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis: Vienna, Austria, 2000; pp. 73–107. [Google Scholar]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and people: The social impact of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carte, L.; McWatters, M.; Daley, E.; Torres, R. Experiencing agricultural failure: Internal migration, tourism and local perceptions of regional change in the Yucatan. Geoforum 2010, 41, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, J.G. The “Yucatan Sydrome”: Its relevance to biological conservation and anthropological activities. In Rights, Resources, Culture,and Conservation in the Land of the Maya; Faust, B.B., Anderson, E.N., Fraizer, J.G., Eds.; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera-Bassols, N.; Toledo, V.M. Ethnoecology of the Yucatec Maya: Symbolism, knowledge and management of natural resources. J. Lat. Am. Geogr. 2005, 4, 9–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle, S.P.; Blois, S.D. Shorter fallow cycles affect the availability of noncrop plant resources in a shifting cultivation system. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Andreson, E.N.; Faust, B.B.; Frazier, J.G. An environmental and cultural history of Maya communities in the Yucatan peninsula. In Rights,Resources, Culture, and Conservation in the land of the Maya; Faust, B.B., Anderson, E.N., Fraizer, J.G., Eds.; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 2004; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, P.; Jeanrenaud, S. Biodiversity and human welfare. In Social Change and Conservation; Ghimire, K.B., Pimbert, M.P., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 46–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimowitz, D.; Sheil, D. Conserving what and for whom? Why conservation should help meet basic human needs in the tropics. Biotropica 2007, 39, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redford, K.H.; Coppolillo, P.; Sanderson, E.W.; Da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Dinerstein, E.; Groves, C.; Mace, G.; Maginnis, S.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Noss, R.; et al. Mapping the conservation landscape. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonilla-Moheno, M.; García-Frapolli, E. Conservation in Context: A Comparison of Conservation Perspectives in a Mexican Protected Area. Sustainability 2012, 4, 2317-2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4092317

Bonilla-Moheno M, García-Frapolli E. Conservation in Context: A Comparison of Conservation Perspectives in a Mexican Protected Area. Sustainability. 2012; 4(9):2317-2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4092317

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonilla-Moheno, Martha, and Eduardo García-Frapolli. 2012. "Conservation in Context: A Comparison of Conservation Perspectives in a Mexican Protected Area" Sustainability 4, no. 9: 2317-2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4092317

APA StyleBonilla-Moheno, M., & García-Frapolli, E. (2012). Conservation in Context: A Comparison of Conservation Perspectives in a Mexican Protected Area. Sustainability, 4(9), 2317-2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4092317