Strengthening Sovereignty: Security and Sustainability in an Era of Climate Change

Abstract

: Using Pakistan and the Arctic as examples, this article examines security challenges arising from climate change. Pakistan is in crisis, and climate change, a transnational phenomenon perhaps better characterized as radical enviro-transformation, is an important reason. Its survival as a state may depend to great extent on how it responds to 2010's devastating floods. In the Arctic, the ice cap is melting faster than predicted, as temperatures there rise faster than in almost any other region. Unmanaged, a complex interplay of climate-related conditions, including large-scale “ecomigration”, may turn resource competition into resource conflict. Radical enviro-transformation has repeatedly overborne the resilience of societies. War is not an inevitable by-product of such transformation, but in the 21st Century climate-related instability, from resource scarcity and “ecomigration”, will likely create increasingly undesirable conditions of insecurity. Weak and failing states are one of today's greatest security challenges. The pace of radical enviro-transformation, unprecedented in human history, is accelerating, especially in the Arctic, where a new, open, rich, and accessible maritime environment is coming into being. The international community must work together to enhance security and stability, promote sustainability, and strengthen sovereignty. Radical enviro-transformation provides ample reason and plentiful opportunity for preventative, collaborative solutions focused broadly on adaptation to climate change, most particularly the effects of “ecomigration”. Nations must work together across the whole of government and with all instruments of national power to create conditions for human transformation—social, political, and economic—to occur stably and sustainably, so as to avoid or lessen the prospects for and consequences of conflict. Collaborative international solutions to environmental issues, i.e., solutions that mobilize and share technology and resources, will build nations and build peace. The military, through “preventative engagement” will play a more and more important role. Further research and analysis is needed to determine what changes in law and policy should be made to facilitate stable and secure “ecomigration” on an international scale, over a long timeline.1. Introduction

Of the socio-political impacts of climate change, its security implications are significant and growing. Among the most significant may be the impact of climate-related migration. As this century becomes the next, a great migration may begin, born of the push and pull among climate change winners and climate change losers. This could trigger or aggravate armed conflict, causing vulnerable places to tip from marginal to unsustainable to collapse. Places with moderating conditions, by opening themselves to exploration and exploitation, could prove irresistibly attractive and likewise trigger or aggravate armed conflict. The scope, scale, and duration of these phenomena may have weighty consequences for the resilience of states and the stability and security of a sustainable state system.

While a prodigious amount of scientific research on climate change itself is occurring, the effects of climate change—direct, indirect, and cumulative—in all spheres—social, political, and economic—and what they mean for human security and national security, are more difficult to assess and predict. At present perhaps the only way to assess and predict these effects, and to extrapolate trends, is by using the recent past as a laboratory of sorts. For that purpose Pakistan and the Arctic stand out as instructive examples of the two main countervailing forces in climate change: injurious and ameliorative, respectively.

This paper makes three key findings. One, climate change is slow- and fast-moving with impacts that are short- and long-lived. Observed changes are outpacing predictions in several regions, such as the Arctic. Some of climate change, in fact a growing part, is therefore better understood as radical enviro-transformation. The main implication of this fact for human security and national security is that climate change is more likely than many now believe to influence armed conflict, international and non-international.

Two, ecomigration could be the most significant by-product of climate change, especially if radical enviro-transformation causes hundreds of millions or even a billion or more persons to move across international borders with no reasonable prospect of return. This is because ecomigration is likely to cause or aggravate armed conflict. The main implication of this fact for human security and national security is that ecomigration on a heretofore unprecedented scale will pose a direct challenge to the resilience and sovereignty of states, which at high enough levels could impact the security and sustainability of the international system itself.

Three, all instruments of national power—diplomatic, informational, military, and economic—must be used to build and implement sustainable solutions to radical enviro-transformation, resource scarcity, and environmental degradation. Stability and security are essential to sustainability; they are likewise fundamental to managing ecomigration. The main implication of this fact for human security and national security is that whole-of-government approaches, with a prominent and expanding military role, will be indispensible to reducing friction and lessening the prospects for armed conflict.

The main body of the paper is divided into five sections. First, we will examine the strategic context being created and likely to be profoundly re-shaped by climate change. Then we will explore how Pakistan and the Arctic quite differently and unevenly illustrate its two main cross-currents. Pakistan and the Arctic make good examples because of their contrasts (one is a push and the other a pull), and because in both cases the strategic consequences of destabilization and conflict are appreciable, and the dangers easy to portend. Other places, such as Bangladesh, due to population density and impoverishment, may be more likely spots for climate change-driven conflict to ignite, but from a geo-strategic perspective either the collapse of nuclear-armed Pakistan or a large-scale resource war in the Arctic would be orders of magnitude more impactful [1]. Next we will consider ecomigration and its likely influence on armed conflict, and last we will delve into approaches to address the potential effect of climate change on state resilience and sovereignty in the 21st Century.

Security, sustainability, and sovereignty are linked as never before, and climate change is changing everything. The International Institute for Sustainable Development says: “No longer is climate change just an environmental problem or an energy challenge. In recent years, it has been recognized as a core development challenge that carries potentially serious implications for international peace and security [2].” The pace, scale, and uncertainty surrounding climate change are already altering security and sustainability paradigms, and the future looks more variable, less predictable, and by many measures in more places, increasingly dire [3]. The challenge to the resilience of individual states and the international system is mounting [4].

Ranked, strategically speaking, someplace between “a” trend and “the” trend, climate change will certainly be challenging and may be dangerous.

Climate change undermines human security in the present day, and will increasingly do so in the future. It does this by reducing people's access to natural resources that are important to sustain their livelihoods. Climate change is also likely to undermine the capacity of states to provide the opportunities and services that help people to sustain their livelihoods, and which help to maintain and build peace. In certain circumstances, these direct and indirect impacts of climate change on human security and the state may in turn increase the risk of violent conflict [3].

Some states appear destined to fail; others to actually disappear, beneath deepening seas, for example [5]. Once-frozen frontiers are opening to exploration and exploitation; more will follow. New economies will be born; old ones will die. States will shrink, states will grow, and new rivalries and alliances will likely form. The question is how much of this will result from, or be exacerbated by, armed conflict instigated or aggravated by climate change.

Climate change of an adverse nature, that is, climate change that decreases the availability of habitable land and natural resources, will amplify the challenges facing seemingly all states, failing and failed states especially. Implosion of unsustainable states may increase the number and size of ungoverned territories and force relocation of large numbers of people, some rendered stateless, all of which will create friction and instability internally and externally. This could make armed conflict more likely.

Climate change of a moderating nature, that is, climate change that increases the availability of habitable land and natural resources, may strengthen states, but no state is certain to derive only benefit from climate change. Competition for resources will likely increase and intensify. The benefits of moderating influences may be offset, in large countries particularly, by debilitating influences. Never before seen levels of migration, internal and external, may intensify threats and exacerbate vulnerabilities. This, too, could make armed conflict more likely.

As the impacts of climate change compound, and especially if they accelerate, the modern state system, now little more than 400 years old, will face mounting pressures, pressures that may spur armed conflict. Of these, unforeseen numbers of environmentally dispossessed persons may be the most challenging. Uncontrolled mass migration is anathema to state sovereignty and national security. Ways and means to manage it must be found, and soon.

For sovereignty to remain strong and resilient, security—maintaining a stable, peaceful international system—and sustainability—living within the Earth's carrying capacity—must adapt to climate change proactively, not reactively. Security and sustainability in an era of climate change will require unified effort around the globe [6]. Curiously, but fortuitously, the dangerous, divisive potentiality of climate change is also a unifying factor, as national interests find common cause in strengthening sovereignty internally and internationally.

Unified action must come in many forms, using all instrument of national power, and must address both mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change, but especially adaptation, will require enormous capability and capacity, some taking forms and methods heretofore unimagined. And given the interdependence of sovereignty, sustainability, and security, the military instrument of national power will play an increasingly important role, likewise in new and different ways.

Preserving sovereignty in an era of climate change will make more adaptive use of the military, across its full spectrum of capability and perhaps beyond, an essential ingredient of security and stability. But the military instrument of national power, like all others, will not be immune from the constraints and limitations that climate change will impose. Sustainability, some have recognized, has already become as important to armed forces as to every other element of society and government. Sustainable, capable, and adaptable military power will be in constant demand even if climate change advances on the low end of the more modest current predictions.

The recent floods in Pakistan and the thinning, shrinking Arctic ice cap illustrate well, by contrast, the trends and challenges derived from climate change. Pakistan presents what may be the destructive effects of climate change on sovereignty and stability in the context of a state that might be characterized as highly stressed, possibly failing. The Arctic presages what at first may appear to be an up-side of climate change, the opening of a new frontier for resource exploitation and new sea lanes of communication and commerce.

Pakistan's floods suggest how a climate change induced shock, most importantly the resulting social, economic, and political stresses, may be beginning to test the resiliency of national sovereignty, with internal, regional, and international implications including its volatile relations with India, the growth of terrorism, and the vulnerability of its nuclear arsenal. The Arctic is different. Here climate change is perceived to offer opportunity, especially to the Arctic states: the United States, Canada, Denmark, Norway, and Russia [7]. But non-Arctic states, e.g., China, Germany, and Japan, are very much interested—and increasingly present—in these northern reaches [8,9].

The Arctic has oil and natural gas, and other valuable commodities, and the unparalleled-in-modern-times environmental make-over occurring there has already started a scramble for petroleum, protein, and position. Also significant is the prospect for seasonal, and perhaps one day continual, circumnavigation of Arctic waters via new maritime superhighways at the top of the world. Competition is not confrontation, and does not necessarily lead to conflict, but a still heavily carbon dependent world in 2050 or beyond may be so stressed by climate change that the rate and extent of geophysical, geopolitical, and geostrategic re-ordering will overwhelm current constraints and offer irresistible inducements, especially in the resource-rich Arctic. The Arctic also demonstrates well why the term “climate change” is inadequate to describe what is really happening there and elsewhere.

2. Climate Change: The Strategic Context

The security implications of climate change are significant and growing. This is because climate change has a strategic dimension. The effects of climate change will be felt globally, across all elements of society—social, political, and economic—and will last indefinitely. In combination with resource scarcity and environmental degradation, climate change must be examined closely for its affect on stability, security, and sovereignty.

The view of things to come is as through a glass, darkly; we know only that our journey to an uncertain future has begun, but how far we will go, and how fast we do not know [10]. The planet is on track, all but unavoidably now it seems, and irreversibly, to warm by at least 3° Celsius this century and perhaps by as much or more than 4° Celsius, bringing it ominously close to the temperature swings that extinguished the dinosaurs and moved Earth in and out of the last Ice Ages [11]. Nothing of this magnitude climatologically has occurred during we humans’ relatively short time in being [12].

Island states apprehend inundation by rising seas. The Sudan and other African states have long been plagued by worsening environmental and climatological conditions. Several places, from the Americas to Asia have been hit by extreme weather disasters attributed to climate change. China worries about creeping desertification and the United States is concerned with the impact of rising temperatures and rising seas, and with the impact of unsustainable irrigation on its major food growing regions. Between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn many unwelcome changes are occurring round the world. To the north and south of the Equatorial band, climate change may be progressing even faster, but in contrast to the middle latitudes where climate change may be making more places less habitable, in higher latitudes more places will likely become habitable. Witness the greening of Greenland, for example.

One thing is certain: “climate change” is not a good or sufficient way to characterize what is happening. The term “climate change” suggests a benign, even welcome switch in latitude, as from Boston to Miami in February. To be sure, some aspects of climate change will be ameliorative in some places and in some ways, for at least a time (and perhaps for a long time, as may occur in Siberia, for example). In that sense there will be climate change “winners” but there will also be climate change “losers”, and likely more of the latter than the former.

This fact alone, that there will be foreseeable winners and losers, may ultimately pose a significant threat to global stability and sovereignty [13]. The apocalyptic but thought-provoking scenarios journalist Gwynne Dyer depicts in Climate Wars may be fanciful, but underlying these visions of climate war is a prophetic possibility—that aspects of climate change, as aggravating factors, could eventually convulse states, regions, and continents violently, with unpredictable results. Like many, Dyer looks to global warming for causes and solutions.

Climate change is not just about temperature, however. It is about chemical changes to the atmosphere and oceans, and sea level rise, severe weather fluctuations, and much more. Imagine, for example, the vast difference in a world where so many live along the coasts, between the eight-inch sea level rise in the 20th Century and a three- to six-foot sea level rise that current conditions could cause to occur this century [14]. All of these things have complex impacts—direct, indirect, and cumulative—on plants, animals, and people, with first-, second-, and third-order social, economic, and political consequences. Moreover, from a sustainability perspective the impact of climate change is additive; resource depletion and pollution were long ago identified as stern challenges to sustainability.

By 1992, according to Limits to Growth, The 30-Year Update, human consumption had already overshot the limits of the Earth's sustainment capacity [15]. Unsustainable economic and population growth, the authors argued, are already on course to cause collapse. Climate change, by further upsetting the equilibrium on which sustainability depends, compounds the difficulty we face, and in ways with which we're only beginning to come to grips.

Perhaps “epochal climate conversion”, “radical environmental state-change”, or “global ecological transformation” (hereafter collectively referred to as “radical enviro-transformation”) would better characterize the events now in motion. Prognoses that were extreme in 2010 may be modest in 2050 and obsolete by 2100. Climate change, it appears, brings with it a new set of tipping points, which like the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back, could initiate dramatic environmental alteration from individually inconsequential burdens. According to the National Science Foundation:

Our challenge is not simply that things are changing fast; there is large uncertainty as to how fast and to what consequences. Human impacts have created a situation without precedent on this planet. Neither current nor past rates of change are dependable guides to what may occur in the future. Feedbacks among environmental processes may accelerate rates of change. Of greater concern is that we may reach critical transition points—tipping points—beyond which abrupt, possibly irreversible changes will ensue [12].

Another critical consideration is humankind itself. A body of literature of which the books Collapse and Questioning Collapse are two leading examples, addresses human aptitude for and resilience to environmental stress, particularly in the intriguing case of Easter Island [16,17]. Collapse theorizes that environmental stresses from deforestation produced social, economic, and political collapse. At the risk of gross oversimplification, Collapse attributes the primary cause of deforestation to human activity, while Questioning Collapse attributes the loss of forest, in the main, to rats.

More accurate as Questioning Collapse may be, it overlooks or under emphasizes an anthropogenic cause: the rats that ate the seeds, without which the palm forests could not regenerate, were an invasive species ostensibly transported to Easter Island by its Polynesian colonizers. Humans may not have consciously denuded the forests essential to survival, but the inhabitants did set in motion a chain of events they did not understand and could not reverse. Against this backdrop, population growth led to increased resource exploitation, which eventually spurred conflict over the rapidly degrading resource base [18].

Easter Island is not the only relevant example of un-sustainability arguably leading to collapse, but it is a stark illustration of the heaviness of the human footprint on a world whose environmental complexities and subtleties remain elusive. It may also illustrate a fallacy in the idea that technological progress will necessarily perpetuate sustainable development, preserve sovereignty, and promote a viable international system [19]. This may have implications for the advocates of geo-engineering who propose to work around various aspects of radical enviro-transformation [20,21].

An even more fierce debate than that which occurred over Easter Island is still raging over the question whether global warming has an anthropogenic cause (viz., human-produced CO2 and other “greenhouse gas” emissions, as per the “Keeling Curve”) [22]. Modern societies are far better equipped to identify and solve environmental problems than were the Easter Islanders, but even modern scientific knowledge is incomplete, and humans seem no less disposed to disregard it for political, religious, and other invidious reasons. As Boston University professor Andrew Bacevich observed: “The trustful acceptance of false solutions for our perplexing problems, Niebuhr wrote a half century ago, adds a touch of pathos to the tragedy of our age [23]”.

One might conclude that the failure to bring the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to fruition is tangible evidence of that fact.

Rather than bold, clarion calls to action, the 15th (Copenhagen) and 16th (Cancun) conferences of the UNFCCC parties produced little [24]. UNFCCC, which sensibly enough is based on the precautionary principle, entered into force in 1994, and though the work is vital, the effort to establish legally binding global emissions limits, through the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and subsequent efforts, encountered familiar nemeses and insurmountable obstacles: politics and money. The United States ratified UNFCCC but not the Kyoto Protocol. Growth-fixated America, not unlike a number of others, is unready to do the heavy cutting, that limiting emissions necessarily entails.

Regardless of the reason(s) UNFCCC has not come to fruition, the fact that it has not and in the foreseeable future will not, most likely means that a more than 2° Celsius increase in global temperature is certain. This, it is widely predicted, will push Earth over the threshold the UNFCCC parties and many climate scientists deem reasonably safe. On a far, far greater scale, all humankind must now wrestle with the issue the Easter Islanders faced in microcosm, namely what to do when environmental transformation can no longer be avoided or mitigated. That is not to suggest that reason no longer exists to mitigate radical enviro-transformation; rather, the emphasis must shift to adaptation. The benefits of mitigation may now be too far removed and too speculative to be realized directly or substantially in the 21st or 22nd Centuries. Such a shift in emphasis from mitigation to adaptation was notable at the May 2010 National Climate Adaptation Summit held in Washington, DC [25].

This, then, is the strategic context for radical enviro-transformation in the 21st Century: climate change of an epochal nature is underway nearly everywhere and is in several regions accelerating, while the international community is not taking and has no plans to take action sufficient to mitigate the transformation in any appreciable way. Some of the transformation is seen in some places as harmful and threatening, while in other places it is seen as positive and welcome. An unfortunate curiosity of climate change is that both circumstances may stimulate ecomigration and thereby increase the likelihood of armed conflict. Climate change is showing itself to be more likely to influence armed conflict, international and non-international, than many now believe.

In the next section we will look at Pakistan, a place where climate change has been and most probably will continue to be harmful and destabilizing.

3. Pakistan: The Impact of Climate Change on a State in Crisis

By the next century a great migration may begin, born of the push and pull among climate change winners and climate change losers. Pakistan, a prospective climate change loser, may push ecomigration. It stands out as an example of the propensity of climate change to be injurious, exacerbating unsustainable conditions and threatening stability, security, and sovereignty. Pakistan's case may be a fight for national survival which, if lost, may generate large-scale out-migration.

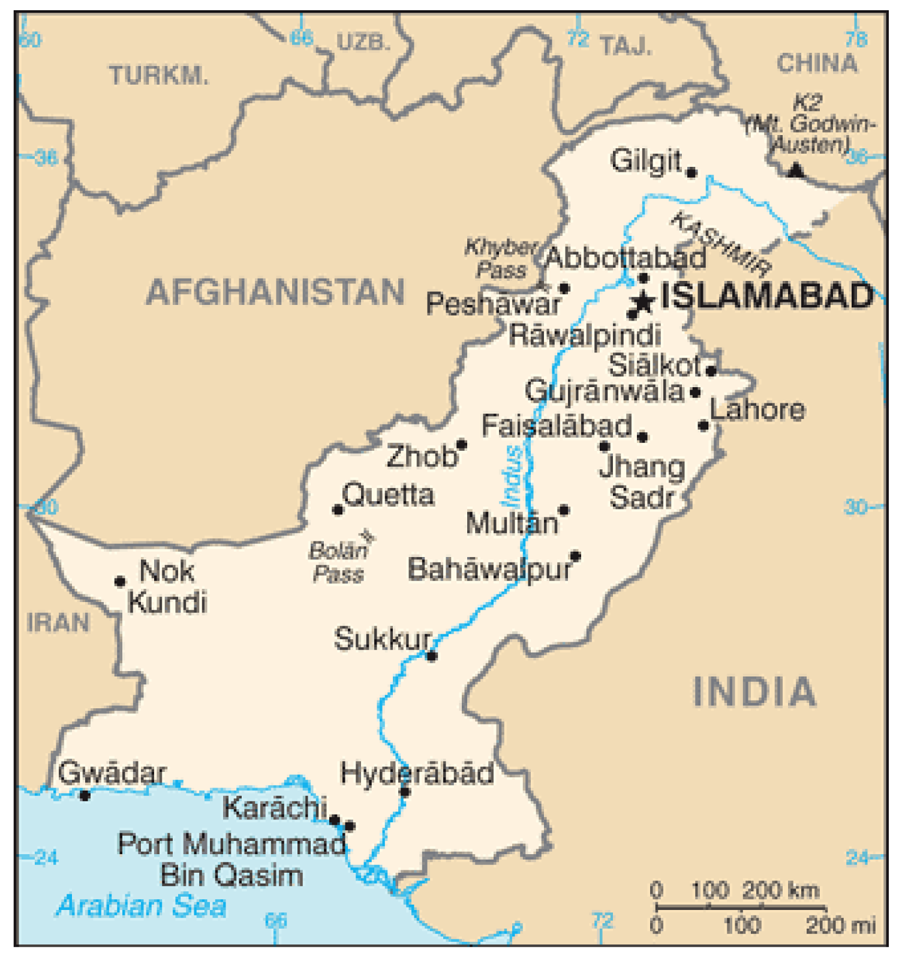

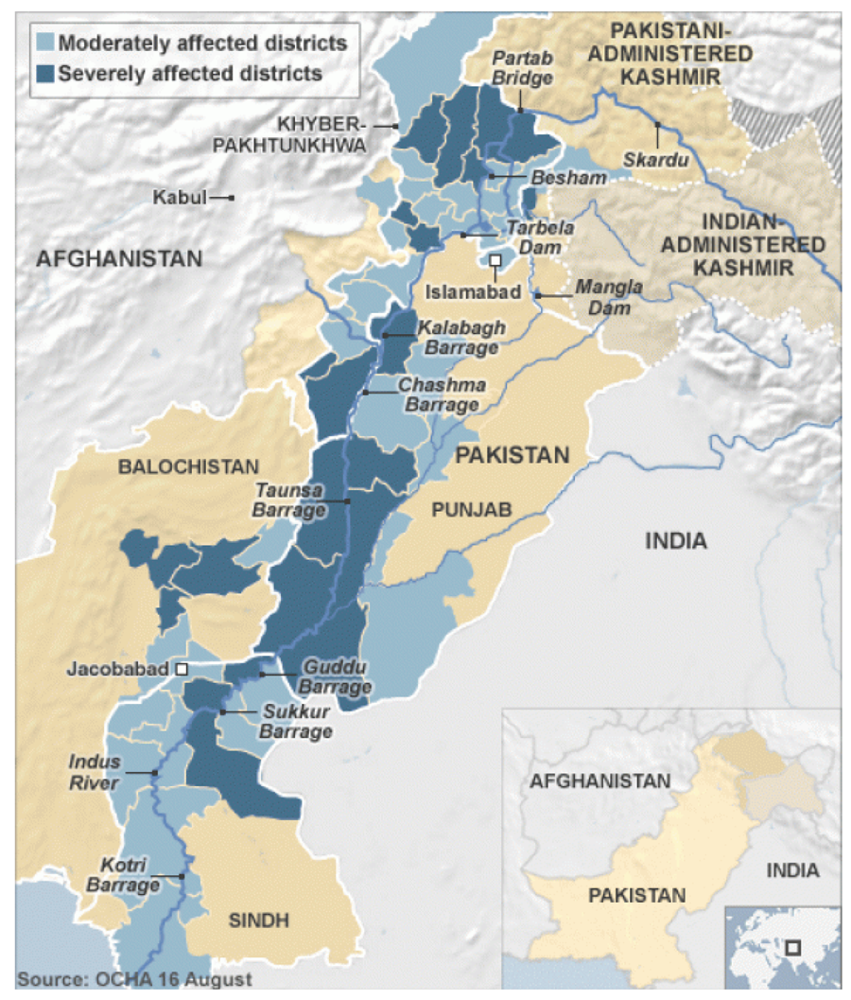

July 2010 was not a good month for Pakistan (Figure 1). According to United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, Pakistan suffered the worst natural disaster ever [26]. A perfect storm resulting from a combination of climate change-related factors—Rossby waves in the upper atmosphere, slowed by global warming, thereby affecting the jet streams and “trapping the weather beneath them”—which were also tied to record heat and wild fires in Russia and to flooding and mudslides in western China, gathered and exploded over a normally dry mountainous part of northwest Pakistan [27-29]. “There's no doubt that clearly the climate change is contributing, a major contributing factor”, World Climate Research Program director Ghassem Asrar asserted [30]. The monsoon-fed, jet stream-steered deluge flooded approximately one-fifth of the country, an area larger than England. Extending from north to south in a widening swath along the Indus River and its tributaries—along which most of Pakistan's peoples reside—flood waters inundated upwards of 7 million hectares of agricultural land in the height of the growing season (Figure 2). In Pakistan, the agricultural sector reportedly counts for more that 21 per cent of gross domestic product and employs as much as 45 per cent of the labor market [31]. The $1 billion or more crop loss, it has been predicted, will have severe impacts on the availability and cost of food [32]. In January 2011, the American Red Cross reported that “more than 4 million people remain in a desperate situation without adequate shelter, and huge areas of land in the southern province of Sindh are still engulfed by floodwaters” [33]. UNICEF contemporaneously reported cases of acute malnutrition in Sindh and other provinces which were aggravated, not caused by the floods [34].

An estimated 20 million people, about the population of New York State, were directly affected; 7–8 million may have been rendered homeless and aid dependent, joining the estimated 36 million around the world who are counted as internally displaced due to natural disaster [31,35]. Electric power generating capacity was hard hit, and by one estimate more than 5,000 miles of roads and railroads were washed out, along with 7,000 schools and 400 health care facilities [31,36]. Damage to irrigation systems will likely protract the adverse impact on agriculture well into 2011 and beyond; a continuing fear of unrest lingers, as Pakistan continues to be in great need of aid [37-39]. In all, according to a Ball State University-University of Tennessee estimate, $7.1 billion is the flood damage price tag, an amount nearly one-fifth of Pakistan's annual budget [36]. Rather than be used for other intended purposes, the 5-year, $7.5 billion U.S. aid package passed by Congress in 2009 may now be consumed just to bring Pakistan back to pre-flood conditions, unless it is judiciously used not only to restore but to modernize and expand critical infrastructure [36].

Pakistan is flood-prone and a great many of its people, especially in the flood-affected region, eke out marginal existences. Poor people, poor land management practices, and poor governmental organization and resources are endemic conditions of dysfunction that weather-borne natural disasters hurriedly and sharply amplify. Internal armed conflict, such as in the Swat Valley where every bridge was lost, is another critical factor, one that placed additional stress on the environment and infrastructure, and displaced large numbers (perhaps millions) of persons even before the rains began [36].

The Pakistani government's response to the floods was slow and on the whole insubstantial. Neither the United Nations nor individual donors all heavily taxed by natural disasters in Haiti and elsewhere, fulfilled all of the remaining need for humanitarian assistance. Interestingly, the initially quickest and most effective internal response was in the areas where the Pakistani army was present in force, due to its military operations against the Taliban going back to 2008 [35]. Foreign militaries, the United States in particular, also played very important rescue, relief, and rebuilding roles, underscoring just how critical military capability and capacity are and will be to aid states in crisis, while preserving security and stability [40].

Pakistan is important to the United States for several reasons, resulting in as much as $15 billion in American security assistance to that country since 2001 [41]. None of the aid, however, was for combating climate vulnerability [35]. The floods portend much about the effects such a mega-sized natural disaster may have on a range of security considerations. Chief among these may be destabilization of social, economic, and political institutions. What will be needed in Pakistan and elsewhere are multinational approaches and solutions, solutions that include military partnerships, humanitarian relief, and long-term development assistance [42].

Beset by a wide and daunting range of security threats and political and economic challenges to its sovereignty and survival besides radical enviro-transformation, Pakistan has entered, or soon will enter, the group of nations whose need to adapt to climate vulnerability is manifest. Worse, its need exceeds its capability and capacity. Pakistan must marshal its resources and unify its effort in ways it has never done. And, it cannot go it alone. Pakistan needs help.

America and others must provide leadership and assistance. Citing work done by the German Advisory Council on Global Change, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) lists Pakistan among the states most vulnerable to climate-related conflict [4]. The White House Council on Environmental Quality's Interagency Climate Change Adaptation Task Force advocates a whole-of-government approach to climate change adaptation [43]. An important component of that approach belongs to USAID whose disaster risk reduction and foreign disaster assistance programs should gear up to address climate change for what it is: radical enviro-transformation. A first-ever Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR) was released by Secretary of State Clinton in December 2010, in which climate change was listed as one of USAID's six focus areas [44].

Another important component of a whole-of-government approach belongs to the military, the “defense” element of the “three D's”: diplomacy, development, and defense. Tsunamis, earthquakes, floods, and other mega-disasters have brought into sharp focus the need for militaries to be proficient in HA/DR (humanitarian assistance and disaster relief), but HA/DR is not enough. Adapting to radical enviro-transformation demands more—in time and resources, in capability and capacity—than HA/DR.

Weather shocks may be the most virulent event now associated with climate change, but despite their devastating impact, as events in Pakistan surely attest, weather shocks are merely a proverbial tip of the climate change iceberg [45]. At full effect radical enviro-transformation is predicted to push large regions into unsustainable conditions, on what in human terms would be considered a permanent basis. For the military this means significant changes to strategy, force structure, and operations, beginning with military-to-military engagement and expanding to broader collective security cooperation.

So what, if anything, do Pakistan's floods teach about resilience? Pakistan is not recovered, but the floods did not, or have not yet, brought down the Pakistani government. Disease has not become epidemic. Broader and more destructive internal conflict has not broken out. Would this have been the case without international humanitarian assistance? Described by The Economist, in October 2010, as no better than “hobbling along”, the Pakistani government faces a monumental rebuilding task [46]. Much of what will or will not happen in the devastated region will likely occur opportunistically with only “feeble” assistance from the provincial or federal governments [46].

Nature abhors a vacuum, and a devastated region with negligible governmental aid or assistance is a vacuum into which groups like the Taliban and al Qaeda, already present in Pakistan, have elsewhere pored and taken firm root. These conditions, which “could set Pakistan back many years (if not decades)”, are ripe for destitute and disaffected persons to become radicalized [31,47]. Natural disaster mishandled can reap a recruiting bonanza for violent causes. Alleged terrorist groups, including Jamaat-ud-Dawa, a religious-based entity linked to the 2008 Mumbai bombing, were among the relief organizations busily and prominently providing aid and organization in the stricken region.

The European Union's Foreign Affairs chief, Catherine Ashton, noted the importance of long-term recovery to Pakistan's prosperity, stability, and security, all of which, she underscored, are “immensely, strategically significant” to the EU and to “the international community as a whole” [31]. Floods, however, may only be the beginning for Pakistan. Himalayan glacier melt and excessive monsoons may continue to give this part of Pakistan much more water than it wants (periodically and somewhat unpredictably), after which, a relatively short-lived period, the region may grow increasingly arid. Soon thereafter it could cease to be agriculturally productive.

The floods greatly compounded the severity of Pakistan's precarious situation but did not bring it to a tipping point. The point of collapse, if there is one, is still somewhere down the road and it remains too uncertain to say whether environmental or other causes will necessarily push Pakistan to that brink. What is certain is that the floods have burdened Pakistan beyond its organic capability and capacity. Were such floods to recur in 2011 or 2012, the prospects for collapse would be greatly magnified. A weakened Pakistan will also be at greater risk if other future environmental conditions get worse, as they more than likely will.

If Pakistan surrenders its sovereignty to radical enviro-transformation, what will be the result? A feral state more hospitable to transnational crime and terrorism? An increasingly infertile land from which all must eventually flee? One thing is certain: environmental conditions are now a major issue and a growing concern for Pakistan, and likely will be indefinitely. Radical enviro-transformation is neither a simple phenomenon nor one to which it will be easy to adapt. The strategies needed to address too much water are not those needed for too little. If coping with the one is already beyond Pakistan's capability, coping with two in succession, with an ill-defined and vexing transition, will be a near certain impossibility without heavy—and sustained—aid and assistance of all kinds. But aid and assistance are not limitless, and the willingness to give them depends on many factors. The question that will surely arise in more and more capitols, as more and more countries are hit harder and harder by radical enviro-transformation, is: “Where, that is, on whom do we spend our time and money?” And if these situations are exacerbated by internal and international armed conflict, the question will become even harder to answer. Radical enviro-transformation may come to impose its own form of natural selection on states. State failure is an ultimate expression of the demise of sovereignty.

Perhaps the most telling question on sovereignty that Pakistan poses to the world today is: “How do we minimize the greatest number of such cases from reaching unmanageable proportions?” Looking around the globe just between the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer, the area first likely to be hit hardest by radical enviro-transformation, a large number of countries are at considerable risk. Many of these would be considered fragile, failing, or failed. And in many, particularly in Africa, armed conflict is occurring or recurring. But even China, Russia, and the United States are experiencing or are set to experience a variety of heavily burdensome impacts, such as sea level rise and desertification. These impacts, alone and in combination with resource scarcity, such as energy insecurity, and environmental degradation, such as from excessive ground water consumption, soil depletion, and unsustainable resource consumption, could affect even powerful states' ability to respond to or to influence world events.

The more these and other majors powers become occupied with their own environmental sustainability and security issues, the less available they will be to aid and assist other states in crisis. This could initiate a downward spiral that might be unrecoverable. It may not be inevitable, but time must surely be growing very short.

Pakistan's floods suggest, but have not proven, that it will be a climate change loser. Nonetheless, the floods have placed Pakistan in a precarious position, making it even more susceptible to instability and hastening its journey to a possible tipping point. Of particular interest will be whether, and if so how fast, monsoonal flooding and Himalayan glacier melt will further upset Pakistan's climate woes and touch off ecomigration which, considering its neighbors—Iran, Afghanistan, China, and India— presents a host of problems even if it does not actually spill across one or more of these borders.

Countries like Pakistan that are already heavily dependent on foreign aid will need more than HA/DR to sustain them. They must adapt themselves to new climatological realities as well as to radical enviro-transformation's foreseeable trends. And while the international community should work together to mitigate and adapt to climate change, the resources available to assist Pakistan may decrease, not increase.

In the next section we will look at climate change from a very different perspective, that of a region—the Arctic—that is poised to become a climate change winner. Climate change is opening the Arctic to exploration and exploitation. Not only does the Arctic contain a resource bonanza, it stands to become the most important East-West/West-East thoroughfare, with a single vital chokepoint—the Bering Strait. Additionally, the northern reaches of the eight Arctic states may become prime real estate coveted not only by internal ecomigrants but by other environmentally dispossessed persons with no better recourse.

4. The Arctic: The New Frontier of Climate Change

The Arctic, a region in which climate conditions are moderating rapidly, may not only prove to be a place where states compete vigorously for badly needed resources, it may pull ecomigrants dispossessed by deteriorating, unsustainable conditions at lower latitudes. Both of these phenomena, but especially in combination, could trigger or aggravate armed conflict. If great migrations occur on the North American or Eurasian continents, the Arctic is where they will—where they must—go.

The Arctic is the region within the Arctic Circle, centered on the 5-million-square-mile Arctic Ocean (Figure 3). It may hold upwards of one quarter of the world's undiscovered oil and gas reserves, a likely remnant of its 55-million-year-old subtropical past [48,49]. It is anything but a forgotten ice barren; rather, it is a hot bed of activity and interest, a frontier that is opening, and quickly. With hundreds of billions of barrels of crude oil and tens of trillions of cubic meters of natural gas (not to mention potentially larger supplies of gas in methane hydrates), the Arctic is vast storehouse of hydrocarbon energy [50]. Besides oil and gas, the Arctic seabed may contain significant deposits of gold, silver, copper, iron, lead, manganese, nickel, platinum, tin, zinc, and diamonds [50]. The key that unlocks these troves is ownership of outer continental shelf [50]. An interactive feature posted on The Guardian website on 5 July 2011 illustrates how much of the Arctic is already involved in industrial activity from fishing to oil and gas extraction and more [51].

In moves reminiscent of imperial powers last seen in the 19th Century, Canada, Russia, and Denmark have planted flags symbolizing new territorial claims. The only notable result thus far was a short-lived diplomatic tiff between Canada and Denmark over the Danish flag planted on Hans Island, which Canada removed and returned [52,53].

Flag-waving nationalistic fervor is not the issue, however. The planting of flags is merely emblematic of the real issue: jockeying for position to make geography-based legal claims to natural resources on the outer continental shelf and to sovereignty-based claims to expand exclusive economic zones into rich fishing grounds [54]. But making claims is one thing, and exploiting them is another. Exploitation demands presence, and the level of worldwide interest in the Arctic is way up, and increasing, as is the level of activity by internal and external actors.

The Arctic could soon become a “zone of conflict”, NATO's supreme commander remarked, in October 2010, in comments urging global leaders to maintain the region as a zone of cooperation [55]. “This”, Admiral James Stavridis said of the fast-changing Arctic, “is the largest environmental state-change on Earth and it brings potential economic, political, and cultural instabilities as well as opportunities that have regional and global implications” [55].

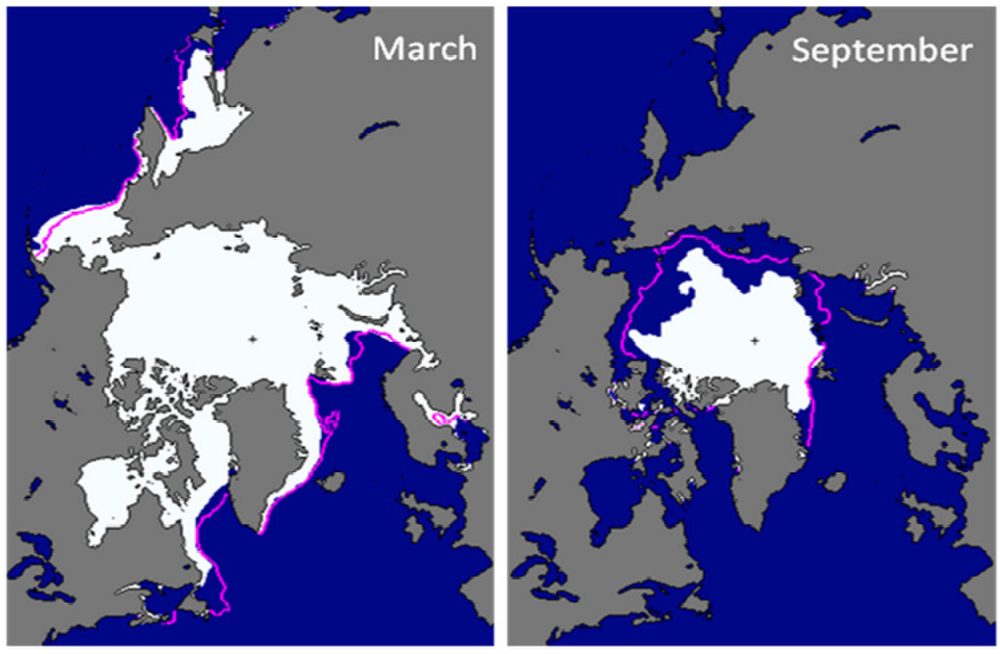

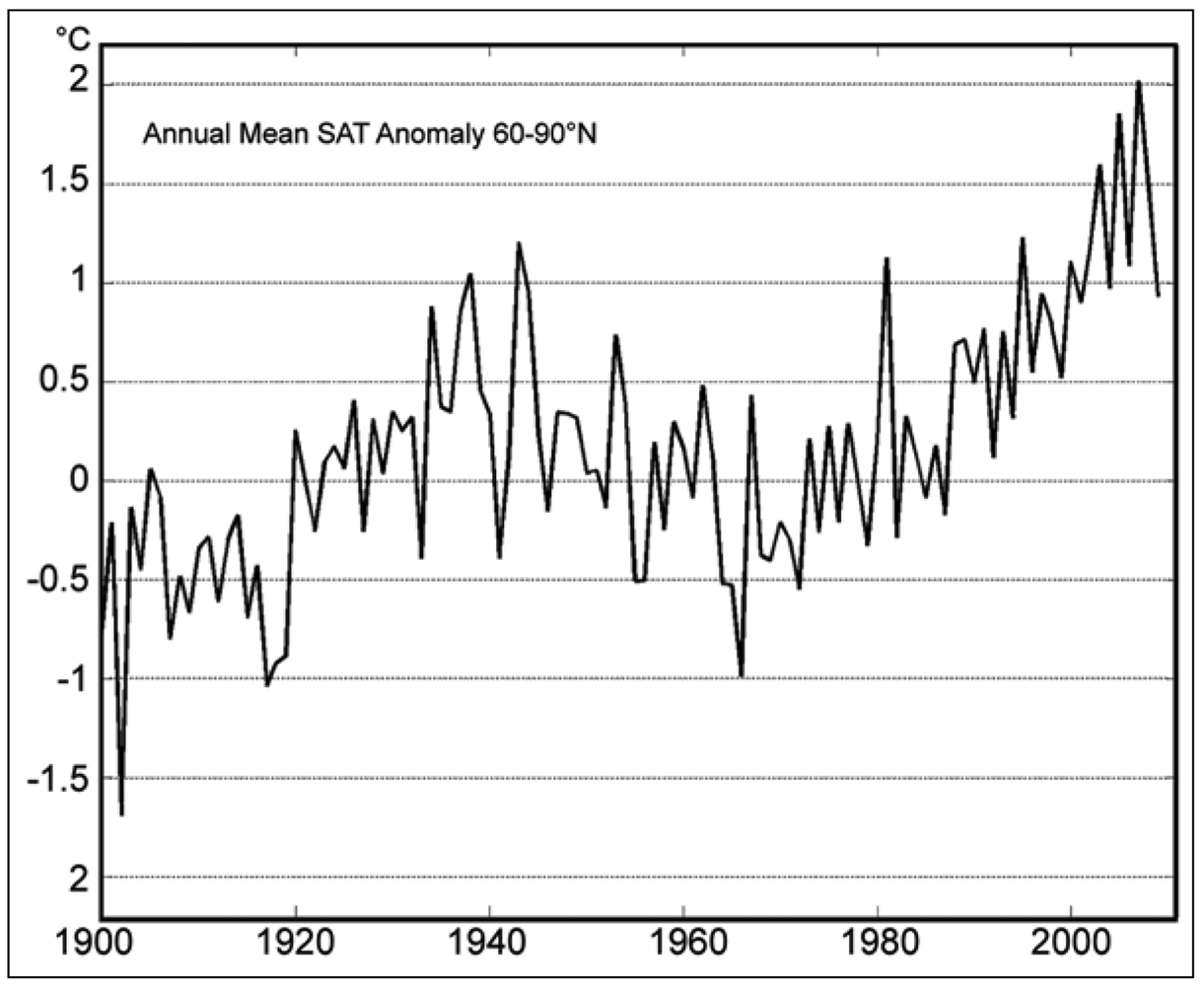

The Arctic is indeed changing fast (Figure 4), and many have taken note [56]. In fact, it may be the place where radical enviro-transformation is moving fastest [12]. A prime cause is an increase in surface temperature more than 0.4° Celsius per decade, e.g., due to deposition of black carbon from the atmosphere that enhances heat absorption and hastens glacier melt [57,58]. The once impenetrable Northwest Passage (Canada-Alaska) and Northern Sea Route (Russia)—sea lanes that could shave thousands of miles from existing Atlantic-Pacific transit routes—became seasonably navigable in the summer of 2008 [59].

The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), on its Arctic Change website, describes the Arctic this way:

The Arctic is a vast, ice-covered ocean that is surrounded by tree-less, frozen land, which is often covered with snow and ice. The rigors of this harsh environment are a challenge to living, working and performing research in the Arctic. None the less, the Arctic is an ecosystem that teems with life including organisms living in the ice, fish and marine mammals living in the sea, birds, land animals such as wolves, caribou and polar bears, and human societies.

The Arctic has been changing in the last 30 years, as noted throughout this website. Some of the clearest indicators of this change are shown below: the warming of spring temperatures in Alaska, the warming of winter temperatures (sic) in N Europe, the loss of sea ice area in the central Arctic, and the conversion of tundra to wetlands and shrub lands in E. Siberia and NW Canada and Alaska. These changes in physical conditions also have impacted marine and terrestrial ecosystems [60].

NOAA's “Arctic Report Card” for 2010 relates that record temperatures, part of a “prolonged and amplified warming trend” (Figure 5), are causing widespread and dramatic impacts on the ice cap, glaciers, and snow covering [61]. Although variable from year-to-year, the ice cap has decreased since 1980 by more than a million square kilometers, according to data tabulated by the U.S. Navy's Task Force Climate Change for its Arctic Roadmap [62,63]. Think California and Texas combined. The effects on native species and native peoples of melting ice and melting permafrost have been dramatic and well chronicled [64].

Russia dominates the Arctic geographically, by size and proximity; it has over 4,000 miles of Arctic coastline, while the U.S. has just over 1,000 [65]. The Cold War-era D.E.W. (defense early warning) line reminds us that distances between countries over the pole are much shorter than distances east to west (or vice versa) in lower latitudes. For example, Canada's Ellsmere Island outpost is closer to Moscow than to Ottawa [66].

Canadian Vice Admiral Dean McFadden, Chief of the Maritime Staff and Commander of the Navy, is famously reported to have quipped that the first thing he'd do if someone invaded Canada from the north is rescue them, but Ottawa is more than a little leery of Moscow's intentions, especially if Siberian and Arctic resources build Russian economic and military power, and fuel Russian aggressiveness [66]. McFadden's American counterpart, Admiral Gary Roughead, Chief of Naval Operations, who established the U.S. Navy's Task Force Climate Change in 2009, is a leading proponent of a long view toward Arctic transformation and its implications for the United States. Both the U.S. and Canada see need for their navies and coast guards to play larger roles in Arctic waters [67,68].

The February 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), which mentions the Arctic and the U.S. Navy's and U.S. Coast Guard's shortcomings there, advocates “cooperative engagement” to build “balanced … human and environmental security” [69]. Commenting on the QDR, Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Michèle Flournoy underscored America's interest in peaceful global commons, of which the Arctic Ocean, as it becomes more heavily trafficked, will become a more significant part [70]. But it is not merely the defense establishment that is interested in climate change; the intelligence community is, too [71].

Thanks in great measure to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and bodies such as the Arctic Council, a creation of the 1996 Ottawa Declaration, the opening of the Arctic frontier, so rich in oil, gas, minerals, and fish, has thus far been decidedly unlike the “Wild West” of American lore. Indeed, the Arctic Council states are pledged to cooperation [72]. But in 30, 40, 50, or more years time, radical enviro-transformation may spawn greater tension in the Arctic and elsewhere around the world, as states compete and then struggle to define, claim, and defend vast areas of resource rich continental shelf [73].

By mid-century Arctic waters could well become a proof-of-concept laboratory for the ideas on sea power of naval theorist Alfred Thayer Mahan. Not since the opening of the Panama Canal, an enlargement of which will be completed in 2012, has a new strategic sea route come into being. Much in naval warfare has changed since Mahan's time, but maritime commerce continues to be an essential ingredient of global prosperity, and thus of sovereignty. It is a strong bet that many nations will want to assert and protect interests, for example, the right to transit the Northern Sea Route despite (or in derogation of) Russian territorial waters claims, as quickly and as broadly as the Arctic transforms. Naval presence and power projection will almost assuredly be one important way the Arctic states will hedge against uncertainty and check overzealousness or aggression.

The U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard are beginning, albeit from positions of marginal preparedness, to envision the capability and capacity needed to assert and defend American interests in what in the next century, if not sooner, may become the most strategically and commercially significant ocean area [52,74,75]. Others will follow suit. Still others, like Russia, may already be ahead [76]. Russian strategy imagines that Arctic resources will be the key to a new military balance of power in the world, and foresees resource-driven conflict in the near future [66]. Prophesies of conflict have many times proven to be self-fulfilling.

Radical enviro-transformation may usher in a new era in which the importance of sea power is resurgent in ways not seen since World War II and not expected since the end of the Cold War. And while a new naval arms race seems implausible at present, the rationale for one may grow increasingly appealing in the second half of this century, particularly if large-scale northward migrations erupt from radical enviro-transformation in the middle latitudes. The early “winners” and “losers” in radical enviro-transformation, some seeking to expand and dominate, others to survive, and perhaps others to push north to find new homes may clash above the Arctic Circle. The great unknown is how violently.

Radical enviro-transformation in the Arctic is quickly transforming this largely inaccessible and inhospitable region into a key strategic crossroads (with a vital chokepoint). Aggressive territorial sea claims by Canada and Russia, once of little import, have taken center stage in the Arctic states' jockeying to enhance their resource wealth and control others' access. Opinion is still divided as to whether resource competition alone will spark armed conflict, but the more commerce expands, the more navies will be present. The more vital the Arctic's resources become, the more likely it will be that navies will be used to assert and defend national interests.

Against this backdrop the pressures of ecomigration may also be at work, that is, if the compound effects of radical enviro-transformation, resource scarcity, and environmental degradation create conditions in lower latitudes that push ecomigration toward a newly inviting Arctic. Territorial integrity and the concomitant right to inviolable borders are fundamental elements of sovereignty and basic premises of national defense. The Arctic states, Russia, for example, may have no desire to allow large numbers of ecomigrants, Chinese, for example, to occupy such prime real estate, Siberia, for example. The international system was not designed for ecomigration to occur on such a grand scale, especially if the migrants are precluded by climate change from returning. Armed conflict would seem all but inevitable under such circumstances, where one state, fearing for its survival, takes aim at territory and resources it feels it must have.

In the next section we will explore the phenomenon of ecomigration and what it might mean if hundreds of millions or even a billion or more persons moved across international borders with no reasonable prospect of ever being able to return.

5. The Principal By-Product of Climate Change: “Ecomigration”

The scope, scale, and duration of ecomigration may have significant consequences for the resilience of states and the stability and security of a sustainable state system. As noted, sovereignty and national security are built on the right of states under international law to maintain their independence and integrity by excluding others. Radical enviro-transformation, if it generates hundreds of millions or even a billion ecomigrants, will sternly challenge a system that not only makes no allowance for ecomigration, but rather is constructed to preclude it [77]. In this way ecomigration is more likely than many now believe to influence armed conflict. Inviolable state borders may hinder peaceful adaptation to climate change.

Charles Darwin, it should be remembered, predicted survival not of the fittest, as such, but rather of the most adaptable [78]. Radical enviro-transformation is pushing adaptation to center-stage. A major component, perhaps the major component, strategically speaking, will likely be exodus, intra- and inter-state, but most significantly the latter, forced on peoples in many places by downward spirals of un-inhabitability and un-sustainability. Mass migration on a planet with 10 billion people is a much different proposition than mass migration even as recently as the 17th Century's Little Ice Age, which spread chaos, crisis, and conflict around the world [66,79]. The more people who must move, the fewer the places they can go, and the more people who will be waiting for them when they get there.

Exodus is not a stable partner to sustainability. It will strain sovereignty severely. The international system based on a construct of states whose sovereign right to defend territorial integrity and control immigration is nearly absolute, is unready. An incalculable amount of time and effort will be required to make it ready given the cardinal changes that must be made in law, policy, and attitude. Witness the fear, anger, and re-crimination generated by ongoing immigration pressures from Africa to Europe and Latin America to the United States, pressures that are merely a drop in the bucket compared to the scope, scale, and duration of ecomigration that radical enviro-transformation may generate.

Looking a half-century or more into the future the greatest danger of conflict arising from radical enviro-transformation will not likely be from implosion of failed states, nor does it appear likely that large-scale intra-state or inter-state conflict will arise over resources, although neither of these can yet be ruled out. Rather, the greatest danger may lie in the allision of peoples. Big, rich, and powerful developed states may be able to accommodate large-scale movements away from coastal regions, along with the enormous infrastructure cost that would result, and may be able for some time to prop-up unsustainable regions that otherwise would fail. Undeveloped failing or failed states, many of which lie in the Equatorial arc of instability, may lack capability or capacity to do the same without massive assistance [80]. Unhappily, the availability of massive assistance may dry up as the number of places that require it increase. If radical enviro-transformation overwhelms the international system's resilience, fights for national survival are foreseeable, probable even.

Resource limits constrain population and growth in what is known as a “Malthusian trap” [81]. Resource degradation, concomitantly, has already been shown to stimulate extensive out-migration, what Indiana University professor Rafael Reuveny dubbed “ecomigration”. Ecomigration, in turn, may lead to conflict at its destination(s) and along the way. This will be especially true in underdeveloped, failing, or failed states [82].

However styled, climate change or radical enviro-transformation is a process, and much like any manufacturing process, it will generate by-products, some of which will be toxic to the environment (viz., the international system). Left untreated, how toxic will ecomigration be? That, and how can the toxic effects of ecomigration be abated, are two vitally important questions.

Conflict arising in this context is likely to be of high intensity [83]. Indeed, the bigger and faster the migration, the greater the potential for conflict [83]. Ecomigration is more likely to originate in underdeveloped, failing, and failed states, i.e., the ones most vulnerable to radical enviro-transformation in the first place [83]. In other words, the effects of ecomigration could be quite toxic, and in spreading out across the international system, will aggravate some of the system's existing insecurities.

A compounding factor is that states with poor economies that depend disproportionately on the environment for sustainment (e.g., agriculture) are especially conflict prone [82]. Scarcity and prospects for decline and starvation are observable causes of conflict and state collapse, as reflected in Environment, Scarcity, and Violence (1999), the signal work of University of Toronto professor Thomas Homer-Dixon [84]. Anticipating the aggravating effect of radical enviro-transformation on environmental scarcity, Homer-Dixon articulated the complex interaction among and compounding effects of environmental factors on social, economic, and political stability [84]. Of Pakistan, its neighbors China and India, and Mexico as well as South Africa, Homer-Dixon wrote: “Some of the countries worst affected by internal environmental scarcity are pivotal; in other words, their stability and well-being profoundly affect broader regional and world security (emphasis in original)” [84].

The symbiotic interaction among climate change, resource scarcity, and environmental degradation will be pernicious. A recent issue of Foreign Policy lists fourteen states as being in critical states of collapse, among them Afghanistan, Haiti, and Pakistan [85]. Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sudan, in turn, are three leading examples of the damaging impacts of radical enviro-transformation on stability and sovereignty. Underdeveloped, failing, and failed states, many of which are already beset with ethnic, religious, and socio-economic animosities, lack capability and capacity, that is, they lack resilience, to adapt to or redress radical enviro-transformation [82]. In failing states, feral cities, and other locales where a growing divide between haves and have-nots is exploitable, hostility and conflict deriving from ecomigration may also produce even more fertile ground for recruiting religiously-motivated terrorists [82].

In sum, ecomigration will most likely commence from an unsustainable location, and if it proceeds to a location that is or becomes unsustainable, intense conflict is predictable, even if the ecomigration remains internal, due to the influence on sustainability on both sides of the border. A sharp upturn in weather-related natural disasters, from 232 in the 1950s, to 1498 in the 1980s, and 3217 from 2000 to 2008, is making things even worse [86]. These disasters are having an increasingly adverse effect on trade, which is forecast, derivatively, to weaken the resilience of the world economy, which may then contribute to intra-state and inter-state violence [86]. From this emerges a sort of unhappy syllogism: as climate disasters increase, political risk increases and trade decreases, thereby decreasing state resilience, which may further increase political risk and decrease trade, and make the state even more vulnerable to the next climate disaster.

In Pakistan ecomigration is at present an internal phenomenon. Conditions have not worsened to a point that out-migration is either sufficiently attractive (to those who have means to do so) or become a survival imperative (to those who would have no choice other than starvation and death). Though it is as of now just an internal phenomenon, the scale is significant. The number of internally displaced persons remains high, and the process of rebuilding and resettlement is slow. Foreign aid and assistance may be the only reason that collapse, partial or total, has not yet come.

In the Arctic today, ecomigration is a marginal issue affecting relatively small numbers of peoples, principally native peoples whose hunting and fishing patterns are being disturbed and in some cases, whose coastal villages have become more vulnerable to tides and storms. But in fast-melting Siberia, Greenland, and Canada, ecomigration could take off. Russia, Denmark (or Greenland itself, if it achieves full independence), and Canada, and to a lesser extent the United States, will in one hundred years or less see ever larger tracts of northern territory become some of the most desirable, productive, and resource-rich real estate on the planet. And other major powers, China, for example, could exert significant influence in this part of the world [8].

One could speculate with concern what path toward conflict might be created if China, having heavily invested itself there, declared a national interest in the flow of oil out of Greenland in the manner that the United States declared a national interest in the flow of oil out of the Middle East. China's need for oil imports is well known and growing. And China faces many climate challenges of its own, making its need for imported oil even greater and more strategically significant.

Viewed objectively—outside the prism of national interest and national security—ecomigration is a logical and likely effective method of adapting to climate change. Were legal means and political will available to do it, ecomigration would make sense. Managed for sustainability, ecomigration, internal and external, could reduce pressures, strengthen states, and alleviate conflict. All of this, by building trust and confidence, well managed ecomigration could do, and some states would see good reason to adopt such a cooperative approach. Many states may not.

Radical enviro-transformation will not respect (i.e., be halted by) international borders. The changes that will come will trespass across the geopolitical landscape with impunity. Ecomigrants, on the other hand, can—and likely will—be stopped or forced out. Their presence will likely be viewed as unwelcome, and without proper management may indeed be harmful and undesirable. With or without state sponsorship, but especially with it, ecomigration may also be perceived as aggression in violation of the U.N. Charter, spurring the aggrieved state to invoke its right to self defense. In any case, ecomigration, internal or external, may cause or contribute to armed conflict, international but more likely non-international.

In the next section we will explore how sovereignty may be strengthened by addressing the security implications of climate change. We will consider how all instruments of national power—diplomatic, informational, military, and economic—must be used to build resilience. To this end, whole-of-government approaches, with a prominent and expanding military role, will be indispensible to reducing friction and lessening the prospects for armed conflict.

6. Strengthening Sovereignty

In the preceding sections we have assessed how the scope, scale, and duration of radical enviro-transformation and ecomigration may have appreciable consequences for the resilience of states and the stability and security of a sustainable state system. In this section we will focus on the strengthening of individual states and the state system, to reduce friction and lessen the likelihood of armed conflict from radical enviro-transformation and ecomigration.

6.1. Climate Change Viewed as a Strategic Trend

From a security perspective, too much and too little can be made of the human and geopolitical implications and environmental, political, and economic consequences of radical enviro-transformation [87]. The amount of attention being paid to these implications and consequences has grown exponentially in the last two years, but, fortunately, the overall level of stridency in the literature has come down measurably, as speculation gives way to analysis. The uncertainties inhering in radical enviro-transformation are reason enough for unease, but a wise consensus appears to be emerging that the nascent strategic trend and its portents for armed conflict should be monitored carefully but approached judiciously, with purposeful urgency but not alarm or aggression.

There is no reason to declare war on climate change, but the magnitude of the challenge radical enviro-transformation presents will require sustained application of all instruments of national power across the entire international system. Typical of environmental issues, solutions to which seem to require instigating crises, the unfulfilled ambitions of UNFCCC to mitigate global warming are testament to the difficulty underlying establishment of international consensus, so long as national interest predominates over collective good. Pakistan and the Arctic, each in their own way, offer insight into ways sovereignty and sustainability may be enhanced by collaborative effort, through what some are now calling “climate security” or “natural security” [88,89].

Transnational phenomena, not conquering states, are increasingly predicted to be the greatest source of insecurity [90]. And of these phenomena climate change, or what we are here calling radical enviro-transformation, is gaining more attention. Among other things, but perhaps most aptly, the phenomenon has been called a strategic trend. But what kind of a trend is it? By affecting where people can live and what resources will be available to them, radical enviro-transformation will escalate and intensify unsustainable practices. This could hasten more extensive and perhaps even more radical enviro-transformation, worsen the fact of and problems associated with resource scarcity, and with great likelihood, if survival is implicated, hurtle peoples and forces into violent confrontation.

The May 2010 National Security Strategy mentions climate change twenty-eight times [91]. It states:

The danger from climate change is real, urgent, and severe. The change wrought by a warming planet will lead to new conflicts over refugees and resources; new suffering from drought and famine; catastrophic natural disasters; and the degradation of land across the globe. The United States will therefore confront climate change based upon clear guidance from the science, and in cooperation with all nations—for there is no effective solution to climate change that does not depend upon all nations taking responsibility for their own actions and for the planet we will leave behind.

A clear call for unified action, the National Security Strategy is echoed only faintly in the out-of-sync 2008 National Defense Strategy, which mentions climate change only indirectly and but twice [92]. It reads:

Current defense policy must account for these areas of uncertainty. As we plan, we must take account of the implications of demographic trends, particularly population growth in much of the developing world and the population deficit in much of the developed world. The interaction of these changes with existing and future resource, environmental, and climate pressures may generate new security challenges. Furthermore, as the relative balance of economic and military power between states shifts, some propelled forward by economic development and resource endowment, others held back by physical pressures or economic and political stagnation, new fears and insecurities will arise, presenting new risks for the international community (emphasis added).

More reflective of the National Security Strategy, the 2010 QDR advocates a more deliberate and sustained strategic approach. It says this:

Climate change will affect DoD in two broad ways. First, climate change will shape the operating environment, roles, and missions that we undertake. The U.S. Global Change Research Program, composed of 13 federal agencies, reported in 2009 that climate-related changes are already being observed in every region of the world, including the United States and its coastal waters.

…

Assessments conducted by the intelligence community indicate that climate change could have significant geopolitical impacts around the world, contributing to poverty, environmental degradation, and the further weakening of fragile governments. Climate change will contribute to food and water scarcity, will increase the spread of disease, and may spur or exacerbate mass migration. While climate change alone does not cause conflict, it may act as an accelerant of instability or conflict, placing a burden to respond on civilian institutions and militaries around the world [93].

The QDR articulates a rationale for re-balancing the U.S. Armed Forces, so that their capabilities and capacities will be optimized to perform effectively across a broad spectrum. Vice Admiral Sam Locklear, as Director, Navy Staff, put it this way: “Our core responsibility is to protect this country. But we are learning how to use our forces in a dual-purpose way that allows us to expand our reach and influence in a good way for the future of society” [94]. And retired Vice Admiral Dennis McGinn, a member of the CNA Corporation Military Advisory Board which produced the paradigm-altering 2007 report National Security and the Threat of Climate Change, said this: “Climate change, energy security, and national security are inextricably linked” [94]. The military, despite its primacy, is not the sole instrument of national power relevant to national security. The closer and more comprehensively we examine transnational phenomena like radical enviro-transformation, the clearer this becomes.

6.2. Smart Power Solutions

The security challenge radical enviro-transformation presents is not a traditional security threat. In most of its phases and aspects it is not solely or pre-dominantly a threat of war of a state-on-state variety. Rather, this non-traditional challenge is ripe for a new approach, a sustainable approach that engages each of the “three D's”. To strike the right balance, the State Department and USAID (as reflected in the QDDR) must continue to move toward solutions that more effectively and more collaboratively enhance security (the defense “D”). Meanwhile, the Defense Department (as reflected in the QDR) must continue to move toward solutions that more effectively and more collaboratively enhance sustainability (the development “D”), all within a framework that strengthens sovereignty and the international system (the diplomacy “D”).

The groundbreaking first QDDR espouses a “smart power” approach in which the civilian and military components of government are equal partners. Sustainable peace, the QDDR theorizes, is built by enhancing other states' ability to address their own challenges, promote development, protect human rights, and provide for their peoples' welfare. Call it nation-building or peace-building, the “three D's” are activities to be shared among the State Department, USAID, and the Defense Department, along with other important contributors such as the Department of Justice, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Commerce.

Reconstruction, as the re-building of sovereignty has long been characterized in defense circles, was traditionally seen by the military almost exclusively as a post-conflict activity. Nation-building, on the other hand, is receiving greater emphasis outside the peer-on-peer context, before, during, and after conflict. This has generated substantial controversy over the potential that such a shift in emphasis will dangerously erode combat power and proficiency. Nonetheless, a blend of kinetic and non-kinetic methods for achieving stability and strengthening sovereignty is growing in significance, relative to combat, in the portfolio of military operations [95].

The call from many quarters is for greater cooperation and greater engagement, domestically and internationally, toward peaceful and sustainable solutions. Another way of putting it, in the parlance of transnational security threats, could be this: pre-emption that works. The application of “smart power” to radical enviro-transformation, from across the whole of government, will build stability and strengthen sovereignty. Water, a critically important resource, is a good example.

Water is the new oil, as water, not oil may become a more likely cause of war [85]. Radical enviro-transformation, it is predicted, will exacerbate food and water shortages. Population growth, consumption (viz., economic growth), environmental pollution, and perhaps most importantly of all “ecomigration”, will further intensify competition over these resources. Shortage-provoked stresses of these and other kinds may significantly affect stability. Water, a historic, if infrequent, cause of conflict, may take center stage [89].

In modern times it is widely considered government's job, directly or indirectly, to deliver or provide access to water, food, and other basic necessities. Radical enviro-transformation, in most of its manifestations, such as in Pakistan, will make it harder, especially for fragile states, to guarantee these critical commodities, weakening it and undercutting its legitimacy [96]. Coincidentally, population growth and increased demand for resources may further foment, exacerbate, and re-ignite armed conflict, making the two—radical enviro-transformation and resource scarcity—a potent one-two combination. If struck too hard or too often, the combination could be a body blow that may stagger the international system. The United Nations (UN) already recognizes this and the importance of natural resources to peace-building [97].

Not everyone agrees that resource wars (i.e., wars over natural resources) have occurred or will materialize; U.S. Naval War College professor Derek Reveron is one [52]. Others, like Amherst College professor Michael Klare, see resource competition as having become the primary organizing principle for and most important purpose of the military instrument of national power [98]. Resource wars, he assesses, will most likely flare up in the Equatorial band, in undeveloped or developing countries with weak or corrupt governments [98]. The similarity is notable between Klare's assessment of the potential for resource wars to occur and others' predictions that conflict will come from radical enviro-transformation.

Resource wars, in the main, are (or would be) a product of the combined effects of unsustainable development and environmental degradation. And if so, the conclusion seems inescapable that radical enviro-transformation will exacerbate the causes, intensity, and consequences of such conflicts. Radical enviro-transformation may cause resource conflict to occur sooner and more frequently, last longer, and impact more, directly and derivatively. Water may indeed become a fighting word. No one, not even the most thrifty, conservation-minded society, can do without it. Past the tipping point, the fight for water may move quickly from the courtroom to the battlefield. And as developments in the Arctic may portend, fights for other resources may also devolve into shooting wars.

It is, of course, not a foregone conclusion that radical enviro-transformation will cause war; indeed, many continue to believe that it will not, except in peculiar circumstances that are few in number and limited in scope (viz., non-international armed conflict). We must use caution, eschewing overly simplistic cause-and-effect explanations for conflicts of this type [99,100]. But as conditions in Bangladesh hint, first as to the effects of sea level rise and then as to the effects of flooding (from Himalayan glacier melt) followed by drought (when glacier-fed rivers dry up), the significance of radical enviro-transformation as a cause of conflict is increasing relative to other conflict stimuli [101]. The too much and then too little water problem is Pakistan's issue as well, although more places seem likely to go straight to too little water, as some of the great irrigators—India, the United States, and China—are on path to experience.

USAID is among those who recognize a significant linkage among climate change, ecomigration, and conflict; it also advocates peace-building [4]. Adaptation to climate change should be conflict-sensitive, USAID advocates [4]. Solutions must lessen the prospects for conflict by strengthening, not weakening, states [4,89]. Pakistan and a growing number of other states need strategies and tools to chart and steer a stable, sustainable course within their own territory and among neighbors. These strategies and tools must be sufficient in number and be wielded in sufficient time to keep radical enviro-transformation from reaching tipping points. Otherwise, social, religious, economic, political, military, and other forces will be unleashed that will threaten its sovereignty. The collision will be felt throughout the region and beyond.

The Environmental Security Initiative of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the UN, and others is a good example of how environmental considerations can be incorporated into conflict avoidance projects for Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sudan, and elsewhere. Intended to enhance adaptability and strengthen sovereignty, the projects build trust among states that might otherwise descend or barge their way into conflict [102]. The Initiative provides a useful framework for understanding the centrality of state resilience (i.e., capability and capacity for adaptation) to the goals of reducing vulnerability to radical enviro-transformation and abating the risk of conflict [3]. Maximizing state capability and capacity—individually (intra-state) and collectively (inter-state)—is key, especially as regards ecomigration.

Because environmental decline owing to radical enviro-transformation could be greater in scope and scale than that which has already induced ecomigration, the prime challenge will be to create stable conditions at the places to which peoples must go, if and when radical enviro-transformation puts them in motion. Incentivizing and orderly preparation for stable and sustainable ecomigration will most enhance the chances for avoiding conflict. The idea that ecomigration can be prevented or stopped by increasing prosperity (i.e., economic growth), is unworkable.

The world cannot simply grow its way out of the ecomigration problem by turning under-developed countries into developed ones [103]. The wheels of radical enviro-transformation are already turning, and some areas are destined for irreversible alteration. The costs of stemming this tide of un-sustainability may prove too great for the places that need it most, and in any event, several of the means for doing so could produce second-order effects (e.g., increased CO2 emissions resulting from fossil fuel guzzling economic growth) that, perversely, will aggravate radical enviro-transformation.