Eco-Physiological Vulnerability of Quararibea funebris in Peri-Urban Landscapes: Integrating Gender and Nature-Based Solutions in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Geographic Context and Hydrological Importance

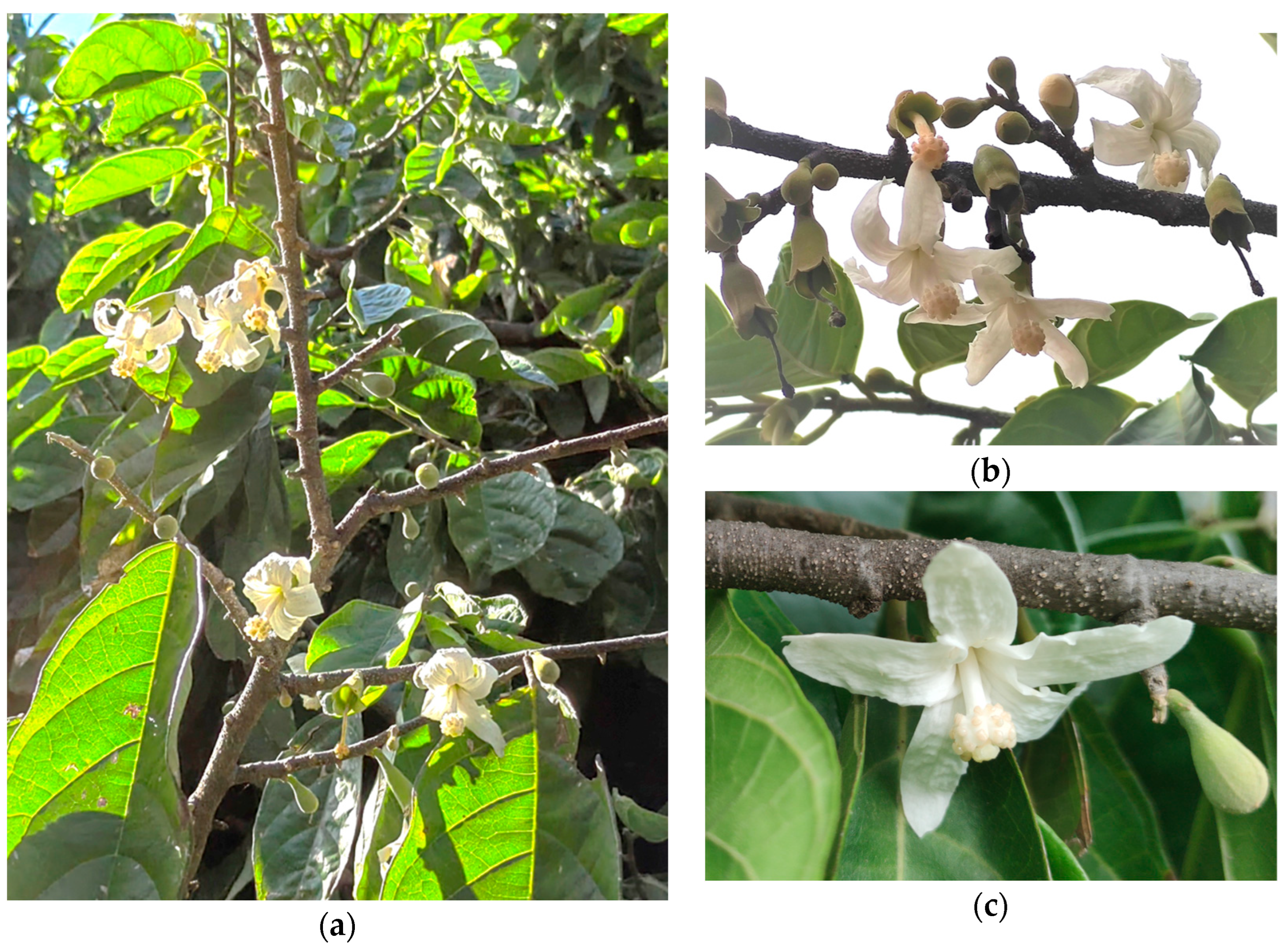

2.2. The Rosital Tree: Study System and Biological Characteristics

2.3. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Landscape Transformation

2.4. Ethnographic Approach and Biocultural Triangulation

3. Results

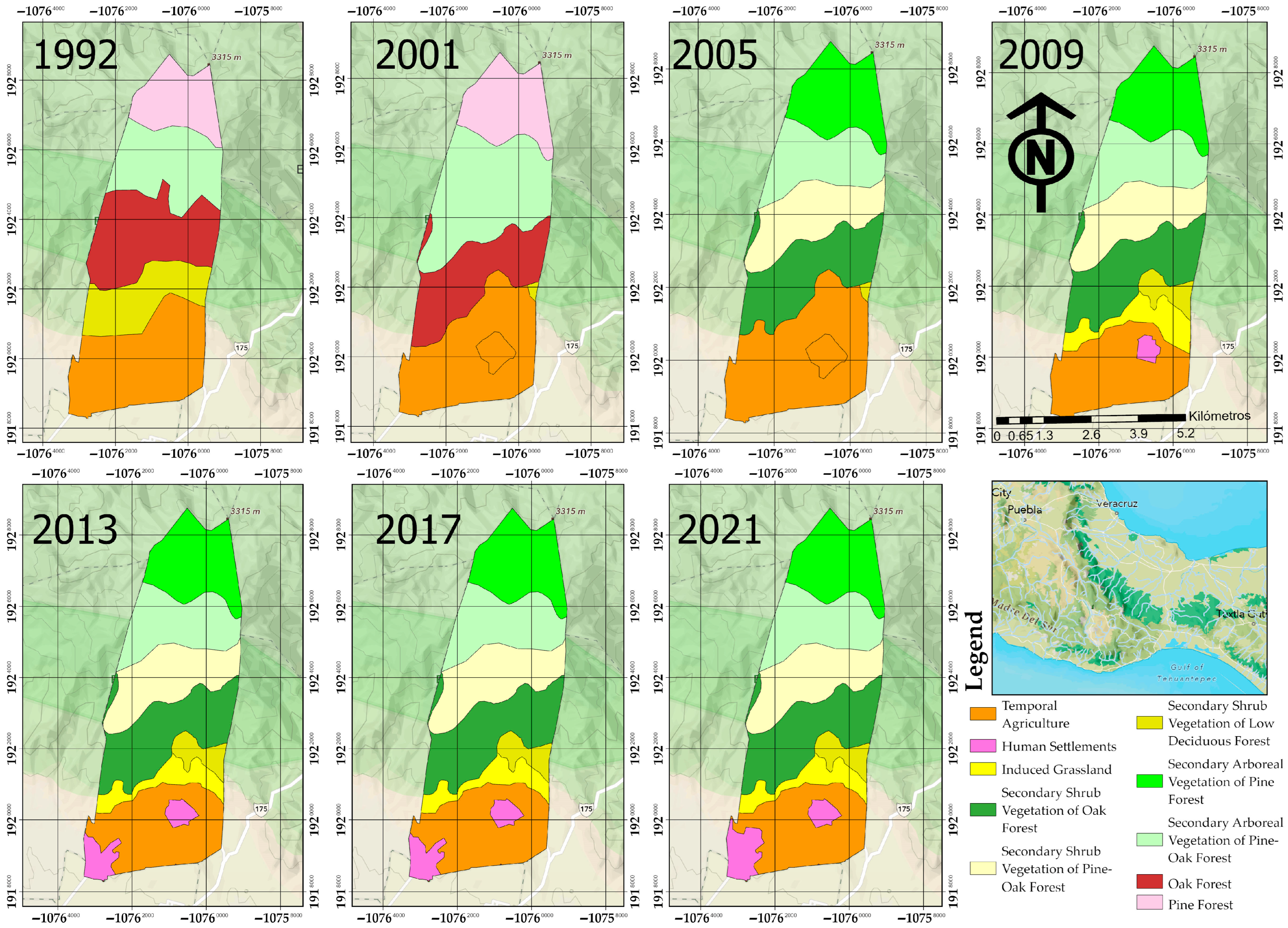

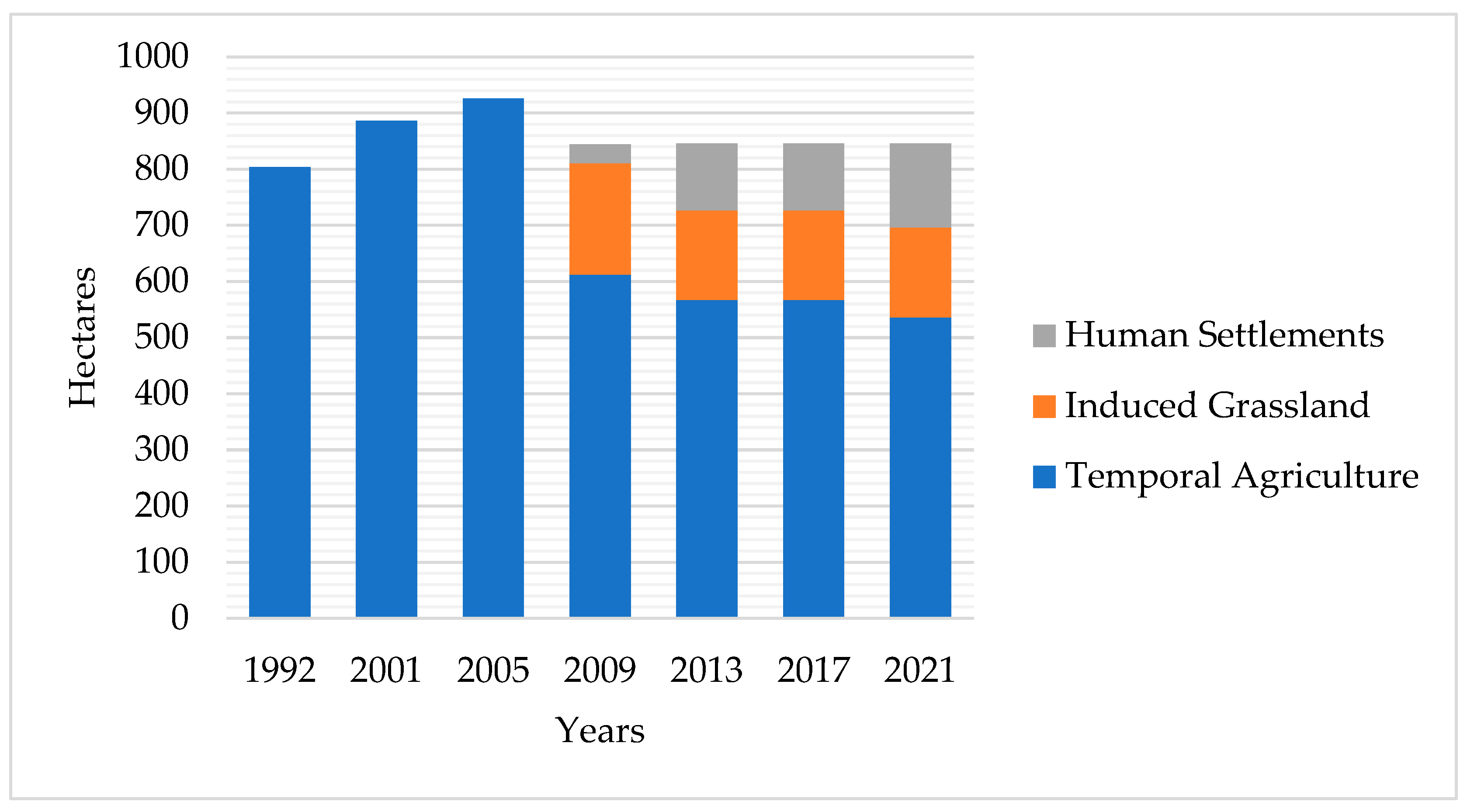

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Landscape Dynamics (1992–2021)

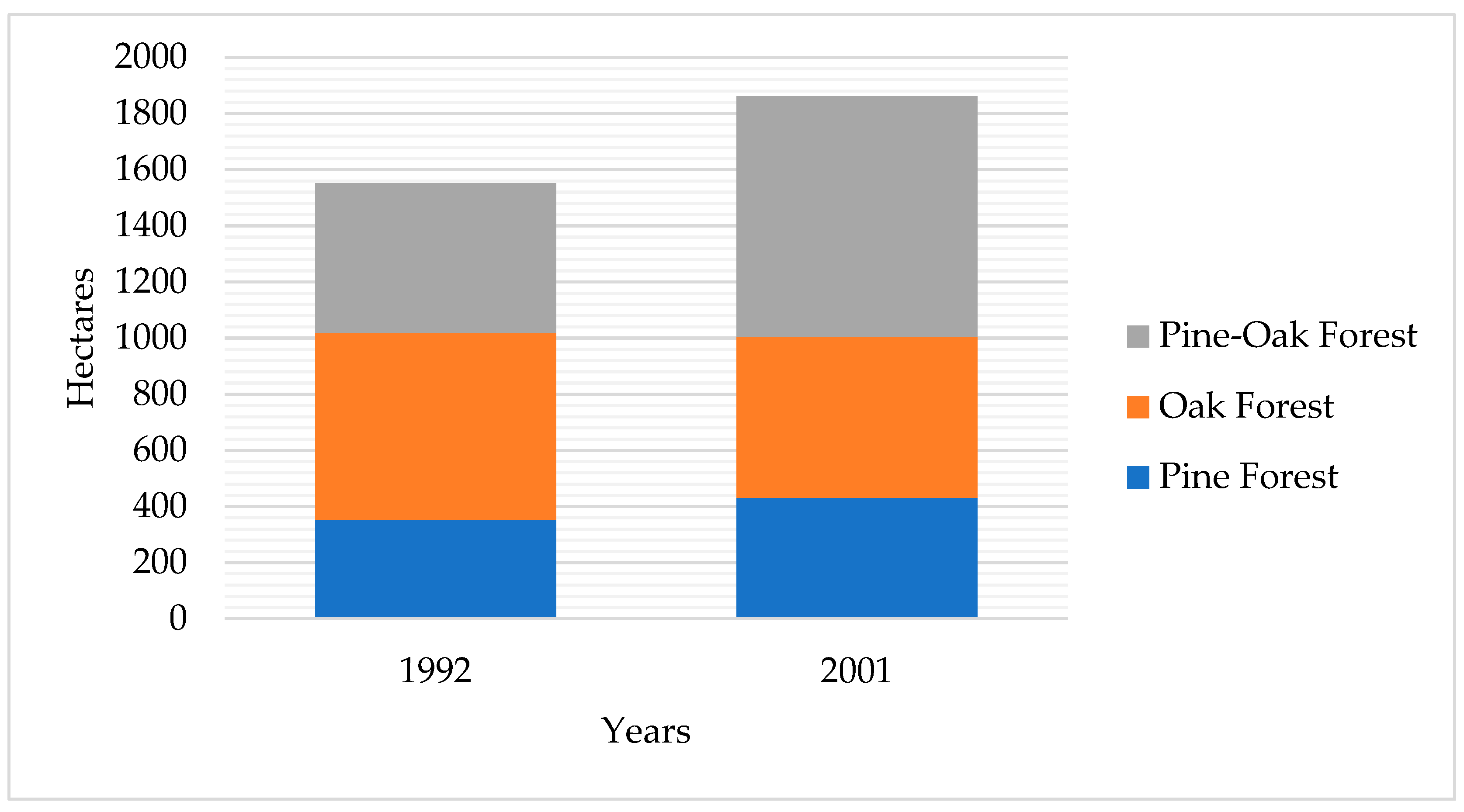

3.1.1. Reconfiguration and Successional Recovery (1992–2001)

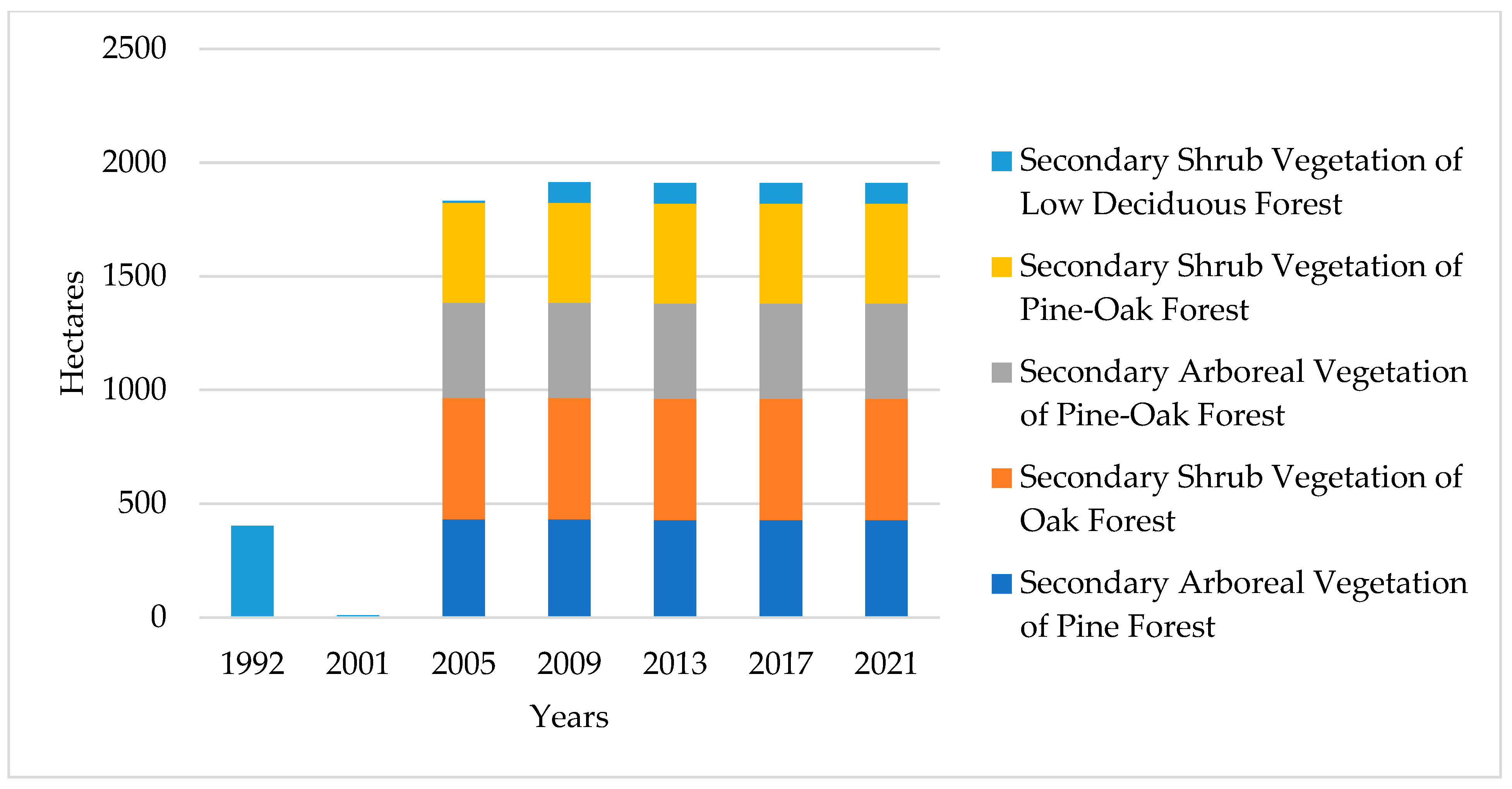

3.1.2. Structural Collapse and Successional Transition (2001–2005)

3.1.3. Urban Consolidation and Fragmentation (2009–2021)

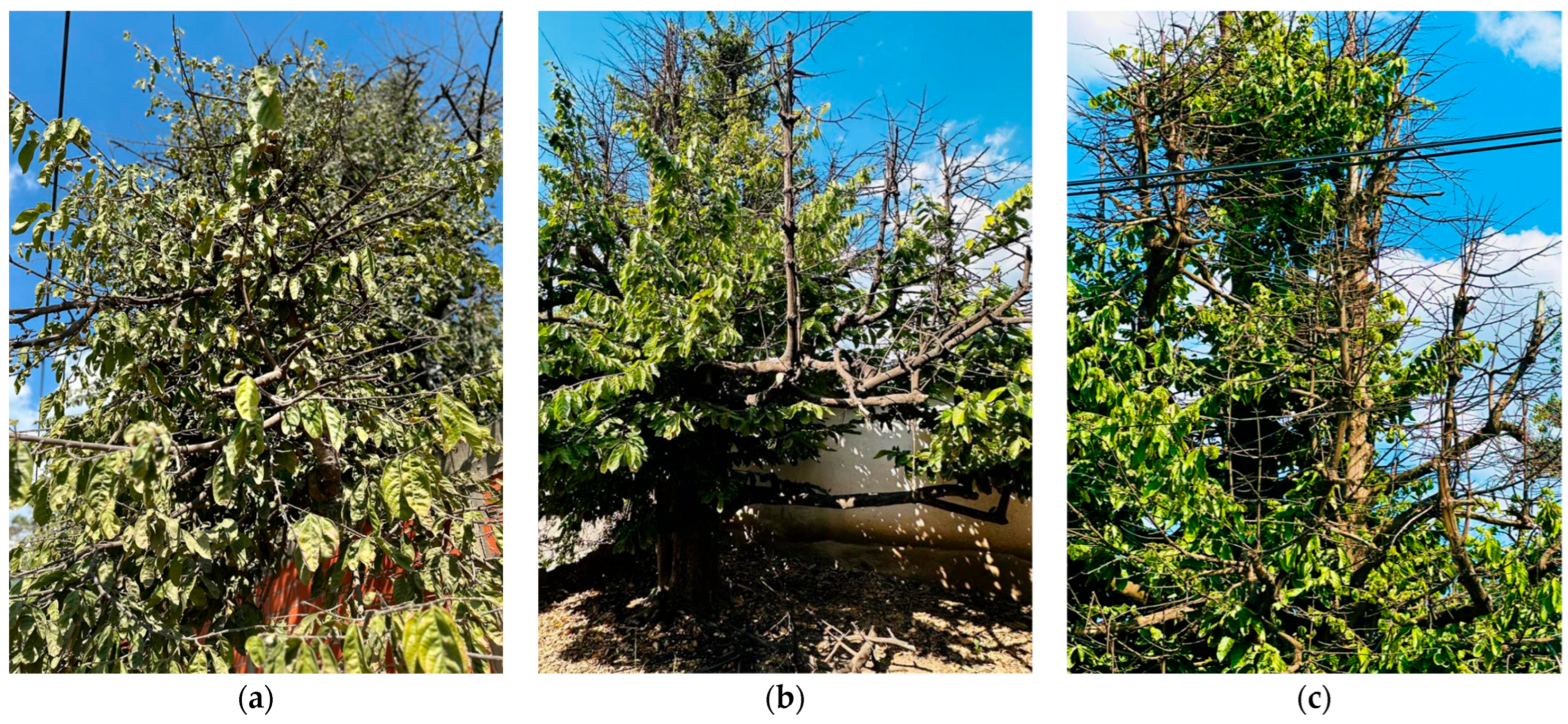

3.2. Eco-Physiological Stress and Structural Vulnerability

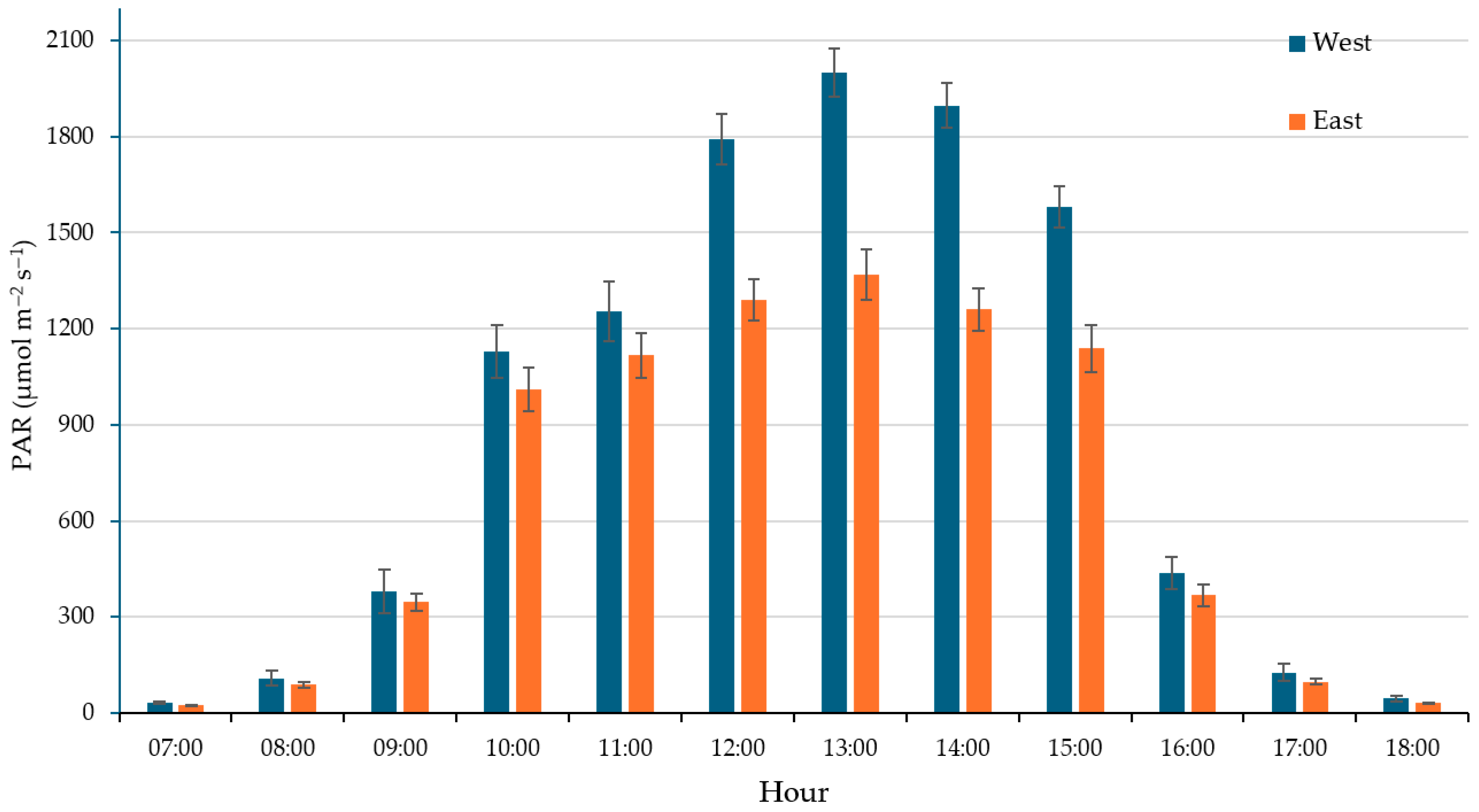

3.2.1. Biometric Stunting and Radiative Stress

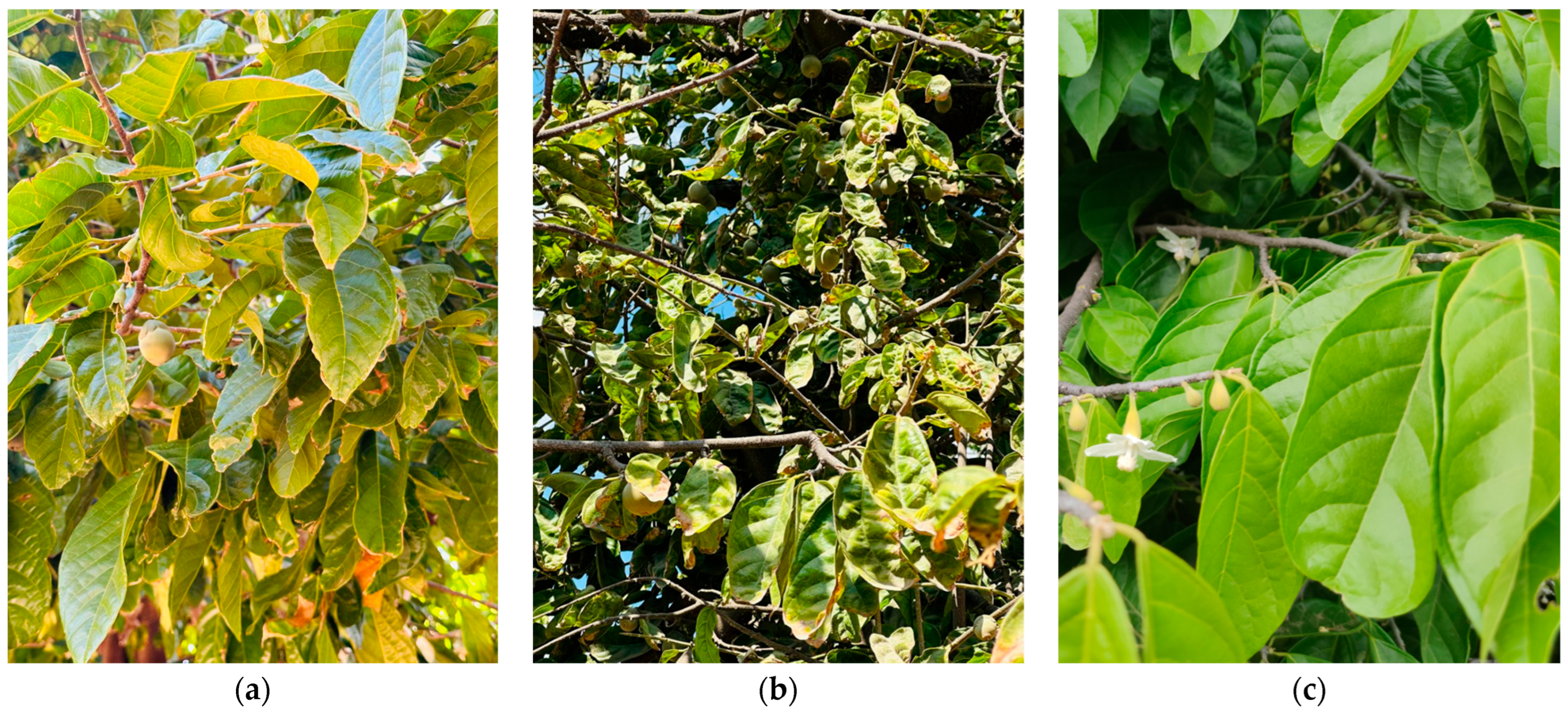

3.2.2. Phenological Dynamics and Productive Yield

3.3. Reproductive Biology and Seed Recalcitrance

3.4. Gender-Based Management and Local Ecological Knowledge (TEK)

3.4.1. Management Intensity and Environmental Subsidy

3.4.2. Harvest Dynamics and Economic Valorization

3.4.3. Post-Harvest Technology and Perception

4. Discussion

4.1. Landscape Transformation and the Mechanism of the Ecological Trap

4.2. Biometric Constraints and Physiological Stress Impact

4.3. Reproductive Vulnerability and the Impossibility of Ex Situ Conservation

4.4. The Gendered Environmental Subsidy

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NbS | Nature-based Solutions |

| DLI | Daily Light Integral |

| PAR | Photosynthetically Active Radiation |

| TEK | Traditional Ecological Knowledge |

Appendix A

References

- Dunlop, T.; Khojasteh, D.; Cohen-Shacham, E.; Glamore, W.; Haghani, M.; van den Bosch, M.; Rizzi, D.; Greve, P.; Felder, S. The evolution and future of research on Nature-based Solutions to address societal challenges. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Blanchard, L.; Anderson, C.; Badgley, G.; Cullenward, D.; Gao, P.; Goulden, M.L.; Haya, B.; Holm, J.A.; Hurteau, M.D.; et al. Towards more effective nature-based climate solutions in global forests. Nature 2025, 643, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivadese, M. Rethinking Nature-Based Solutions: Unintended Consequences, Ancient Wisdom, and the Limits of Nature. Land 2025, 14, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauleit, S.; Zölch, T.; Hansen, R.; Randrup, T.B.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. Nature-Based Solutions and Climate Change—Four Shades of Green. In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages Between Science, Policy and Practice; Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B.; García, J. What are Nature-based solutions (NBS)? Setting core ideas for concept clarification. Nat.-Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, L.; Chua, C.; Kirkwood, N.; Keesstra, S.; Veraart, J.; Verhagen, J.; Visser, S.; Kragt, M.; Linderhof, V.; Appelman, W.; et al. Nature-based solutions as building blocks for the transition towards sustainable climate-resilient food systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, T.D.; Sarukhán, J. Arboles Tropicales de México: Manual para la Identificación de las Principales Especies; Universidad Autónoma de México, Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2005; p. 523. [Google Scholar]

- Alverson, W.S. Matisia and Quararibea (Bombacaceae) should be retained as separete genera. TAXON 1989, 38, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, L. Tejate, Oaxaca’s Favorite Drink Then and Now—Culinary Backstreets. Available online: https://culinarybackstreets.com/stories/oaxaca/liquid-assets-tejate-oaxacas-drink-of-the-gods (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Soleri, D.; Cleveland, D.A.; Aragón Cuevas, F.; Jimenez, V.; Wang, M.C. Traditional Foods, Globalization, Migration, and Public and Planetary Health: The Case of Tejate, a Maize and Cacao Beverage in Oaxacalifornia. Challenges 2023, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Fernández, M.; Juárez Trujillo, N.; Mendoza, M.; Monribot-Villanueva, J.; Guerrero-Analco, J. Nutraceutical potential, and antioxidant and antibacterial properties of Quararibea funebris flowers. Food Chem. 2023, 411, 135529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Manríquez, G.; Cornejo-Tenorio, G. Tree fruit traits diversity in the tropical rain forest of Mexico. Acta Bot. Mex. 2010, 90, 51–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, G.; Winter, K.; Matsubara, S.; Krause, B.; Jahns, P.; Virgo, A.; Aranda, J.; Garcia, M. Photosynthesis, photoprotection, and growth of shade-tolerant tropical tree seedlings under full sunlight. Photosynth. Res. 2012, 113, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, J.; Holcombe, V.; Rajapakse, N.; Layne, D. The Effect of Daily Light Integral on Bedding Plant Growth and Flowering. HortScience 2005, 40, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Alderson, P.G.; Wright, C.J. Solar irradiance level alters the growth of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and its content of volatile oils. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 63, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, J.; Prathibha, M.D.; Singh, P.; Choyal, P.; Mishra, U.N.; Saha, D.; Kumar, R.; Anuragi, H.; Pandey, S.; Bose, B.; et al. Plant photosynthesis under abiotic stresses: Damages, adaptive, and signaling mechanisms. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SADER. Orgullo Oaxaca. Tejate: La Bebida de Los Dioses. Available online: https://www.oaxaca.gob.mx/sedeco/orgullo-oaxaca/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Wang, Z.; Fu, B.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Lu, N. Escaping social–ecological traps through ecological restoration and socioeconomic development in China’s Loess Plateau. People Nat. 2023, 5, 1364–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuñiga-Palacios, J.; Zuria, I.; Castellanos, I.; Lara, C.; Sánchez-Rojas, G. What do we know (and need to know) about the role of urban habitats as ecological traps? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colléony, A.; Shwartz, A. Beyond Assuming Co-Benefits in Nature-Based Solutions: A Human-Centered Approach to Optimize Social and Ecological Outcomes for Advancing Sustainable Urban Planning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.G. The growth paradox, sustainable development, and business strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3079–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, G.M. Whose conservation? Science 2014, 345, 1558–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R. Las Guardianas del Tejate. Available online: https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/articulo/menu/2017/03/7/las-guardianas-del-tejate/ (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- SISPLADE. Sistema de Planeación para el Desarrollo—San Andrés Huayápam. Available online: https://sisplade.oaxaca.gob.mx/sisplade/smPublicacionesMunicipio.aspx?idMunicipio=91#divPlanesT (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Vázquez-Negrín, I.; Castillo-Acosta, O.; Valdez-Hernández, J. Estructura y composición florística de la selva alta perennifolia en el ejido Niños Héroes Tenosique, Tabasco, México. Polibotánica 2011, 32, 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Boutreux, T.; Bourgeois, M.; Bellec, A.; Commeaux, F.; Kaufmann, B. Addressing the sustainable urbanism paradox: Tipping points for the operational reconciliation of dense and green morphologies. npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevochtchikova, M.; Hernández Flores, J. How can social-ecological system trajectories be understood? An investigation of conceptualization through a systematic literature review. Estud. Demográficos Urbanos 2025, 40, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-García, C.A.; Orantes-García, C.; Moreno-Moreno, R.A.; Farrera-Sarmiento, Ó. Efecto del almacenamiento sobre la viabilidad y germinación de dos especies arbóreas tropicales. Ecosistemas Recur. Agropecu. 2018, 5, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEIE. Análisis Municipal. Consulta de Información Municipal. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/san-andres-huayapam (accessed on 2 February 2026).

- Miranda, F. Tejate, Sabores, Conocimiento y Una Forma de Vida Que se Hereda Entre Mujeres de Oaxaca. Available online: https://oaxaca.eluniversal.com.mx/mas-de-oaxaca/tejate-sabores-conocimiento-y-una-forma-de-vida-que-se-hereda-entre-mujeres-de-oaxaca/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Mulato, A. El Tejate, Detrás de la Bebida Mexicana Que Mantiene Vivo el Mundo Prehispánico en Cada Sorbo. Available online: https://www.trtespanol.com/article/ebce73060577 (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- PMD. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo 2020–2022. San Andrés Huayapam. Available online: https://sisplade.oaxaca.gob.mx/bm_sim_services/PlanesMunicipales/2020_2022_/091.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- PMD. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo 2023–2025. San Andrés Huayapam. Available online: https://huayapam.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/PMD-HUAYAPAM-06.MAY_.25.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- PMD. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo 2011–2013. San Andrés Huayapam. Available online: https://sisplade.oaxaca.gob.mx/bm_sim_services/PlanesMunicipales/2011_2013/091.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Congreso de Oaxaca Dictamen Num. 56. Tejate como Patrimonio Cultural del Estado de Oaxaca. Available online: https://www.congresooaxaca.gob.mx/docs65.congresooaxaca.gob.mx/dictamen/1186.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2026).

- Korczynski, P.C.; Logan, J.; Faust, J.E. Mapping Monthly Distribution of Daily Light Integrals across the Contiguous United States. HortTechnology 2001, 12, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT Software, 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2023.

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie I. Continuo Nacional. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007020 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie II. Continuo Nacional. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007021 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie III. Continuo Nacional. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007022 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie IV. Conjunto Nacional. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007023 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie V. Conjunto Nacional. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825007024 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie VI. Conjunto Nacional. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463598459 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- INEGI. Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de la Carta de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. Escala 1:250 000. Serie VII. Conjunto Nacional. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463842781 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- ESRI. ArcGIS PRO, 3.5.4; Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI): Redlands, CA, USA, 2025.

- INEGI. Diccionario de Datos de Uso del Suelo y Vegetación. (Vectorial) Escala 1:250 000, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, INEGI.: Mexico City, Mexico, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Servicio Meteorológico Nacional. CONAGUA. Normales Climatológica por Estado. Available online: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/tools/RESOURCES/Normales_Climatologicas/Normales9120/oax/nor9120_20079.txt (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Foster, L.; Sloan, L.; Clark, T.; Bryman, A. Bryman’s Social Research Methods, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M. What Is Qualitative Research? An Overview and Guidelines. Australas. Mark. J. 2025, 33, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport, F. Combining methodological approaches in research: Ethnography and interpretive phenomenology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coordinación de Comunicación Social. Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca. Recibe Certificación Hecho en Oaxaca la Unión de Productores de Tejate Sabor a Huayápam A.C. Available online: https://www.oaxaca.gob.mx/comunicacion/recibe-certificacion-hecho-en-oaxaca-la-union-de-productores-de-tejate-sabor-a-huayapam-a-c/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Arias-Valencia, M.M. Principles, Scope, and Limitations of the Methodological Triangulation. Investig. Educ. Enfermería 2022, 40, e03. [Google Scholar]

- López-Sánchez, M.P.; Alberich, T.; Aviñó, D.; Francés García, F.; Ruiz-Azarola, A.; Villasante, T. Herramientas y métodos participativos para la acción comunitaria. Informe SESPAS 2018. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, D.R.A.; Stark, S.C.; Valbuena, R.; Broadbent, E.N.; Silva, T.S.F.; de Resende, A.F.; Ferreira, M.P.; Cardil, A.; Silva, C.A.; Amazonas, N.; et al. A new era in forest restoration monitoring. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, T. Monitoring Forest Biodiversity: Improving Conservation Through Ecologically Responsible Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 1–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perz, S.G.; Arteaga, M.; Baudoin Farah, A.; Brown, I.F.; Mendoza, E.R.H.; De Paula, Y.A.P.; Perales Yabar, L.M.; Pimentel, A.D.S.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Rioja-Ballivián, G.; et al. Participatory action research for conservation and development: Experiences from the amazon. Sustainability 2021, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E. Análisis del turismo en huayapam, desde la perspectiva de género y en el contexto de pandemia. In Innovación, Turismo y Perspectiva de Genero en el Desarrollo Regional; Rózga-Luter, R.E., Serrano-Oswald, S.E., Mota-Flores, V.E., Eds.; Recuperación transformadora de los territorios con equidad y sostenibilidad; UNAM-AMECIDER: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 2021; Volume V, pp. 517–534. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco-Murguía, A.; Medina, E.; Garcia, R.; Bray, D. Cambios en la cobertura arbolada de comunidades indígenas con y sin iniciativas de conservación, en Oaxaca, México. Investig. Geográficas 2014, 22, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wolff, N.H.; Masuda, Y.J.; Meijaard, E.; Wells, J.A.; Game, E.T. Impacts of tropical deforestation on local temperature and human well-being perceptions. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 52, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, H.J.; Lambin, E.F. Proximate Causes and Underlying Driving Forces of Tropical Deforestation: Tropical forests are disappearing as the result of many pressures, both local and regional, acting in various combinations in different geographical locations. BioScience 2002, 52, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenov, D.; Borišev, M.; Nikolić, N.; Horak, R.; Pajević, S. Physiological and Biochemical Indicators of Urban Environmental Stress in Tilia, Celtis, and Platanus: A Functional Trait-Based Approach. Plants 2025, 14, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaja, M.; Kołton, A.; Muras, P. The Complex Issue of Urban Trees—Stress Factor Accumulation and Ecological Service Possibilities. Forests 2020, 11, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Toledo, L.; Martínez, M.; van Breugel, M.; Sterck, F.J. Soil and light effects on the sapling performance of the shade-tolerant species Brosimum alicastrum (Moraceae) in a Mexican tropical rain forest. J. Trop. Ecol. 2008, 24, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, R.; Kumar, A.; Masu, M.M.; Kanade, N.; Pant, D. Alternate Bearing in Fruit Crops: Causes and Control Measures. Asian J. Agric. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, B.W.T.; van Zyl, L. The Environmental Light Characteristics of Forest Under Different Logging Regimes. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas-Deyá, A.; González-Anduaga, G.M.; Medina-Torres, L.; Balderas-López, J.L.; Sandoval-Flores, S.D.; Gutiérrez-Rodelo, C.; Manero, O.; Navarrete, A. Fundamental understanding of Quararibea funebris flowers mucilage: An evaluation of chemical composition, rheological properties, and cytotoxic estimation. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 167, 111431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ramírez, I.F.; Cariño-Sarabia, A.; Castaño-Tostado, E.; Vázquez-Landaverde, P.A.; Ramos-Gómez, M.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Amaya-Llano, S.L. Chemical and sensorial characterization of Tejate, a Mexican traditional maize-cocoa beverage, and improvement of its nutritional value by protein addition. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 3548–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelo, A.; Soleri, D.; Wacher, C.; Sánchez-Chinchillas, A.; Argote, R.M. Chemical and nutritional composition of tejate, a traditional maize and cacao beverage from the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2012, 67, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundathil, A.; Varga, Z.; Szalay, K.; Sipos, L.; Jung, A. Daily Light Integral (DLI) Mapping Challenges in a Central European Country (Slovakia). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; Martínez-Tomás, S.H.; Tavera-Cortés, M.E. Nature-Based Solutions for Conservation and Food Sovereignty in Indigenous Communities of Oaxaca. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico Oaxaca. La Unión de Productores de Tejate “Sabor a Huayapam A.C.” Presentó su Marca Colectiva. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lf3J4_ttBAI (accessed on 5 December 2025).

| Standardized Category | Original INEGI Labels (as Identified in Series I to VII) | Functional Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Forest | Pine Forest, Oak Forest, and Pine-Oak Forest | Mature forest ecosystems with closed canopy and high microclimatic buffering |

| Secondary Vegetation | Secondary Arboreal and Shrub Vegetation of Pine, Oak, Pine-Oak, and Low Deciduous Forest. | Successional stages resulting from disturbance; fragmented cover with reduced capacity to regulate irradiance. |

| Agriculture & Grassland | Rainfed Agriculture and Induced Grassland. | Areas of complete canopy removal and high soil exposure, forcing dependency on manual irrigation. |

| Human Settlements | Human Settlements. | Urban expansion and soil sealing that creates urban heat islands. |

| Land Type Use | 1992 | 2001 | 2005 | 2009 | 2013 | 2017 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine Forest | 353 | 432 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Secondary Arboreal Vegetation of Pine Forest | 0 | 0 | 432 | 432 | 429 | 429 | 429 |

| Oak Forest | 665 | 572 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Secondary Shrub Vegetation of Oak Forest | 0 | 0 | 533 | 533 | 533 | 533 | 533 |

| Pine-Oak Forest | 534 | 858 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Secondary Arboreal Vegetation of Pine-Oak Forest | 0 | 0 | 419 | 419 | 419 | 419 | 419 |

| Secondary Shrub Vegetation of Pine-Oak Forest | 0 | 0 | 439 | 439 | 439 | 439 | 439 |

| Agriculture | 804 | 886 | 926 | 612 | 567 | 567 | 536 |

| Secondary Shrub Vegetation of Low Deciduous Forest | 402 | 9 | 9 | 91 | 91 | 91 | 91 |

| Induced Grassland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 199 | 160 | 160 | 160 |

| Human Settlements | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 119 | 119 | 150 |

| Normal Climate Parameter | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Annual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Temperature (°C) | 19.6 | 21.4 | 23.5 | 25.4 | 25.3 | 23.7 | 23.0 | 23.0 | 22.6 | 21.9 | 20.6 | 20.0 | 22.5 |

| Maximum Temperature (°C) | 28.9 | 31.1 | 33.3 | 34.9 | 33.8 | 30.9 | 30.1 | 30.0 | 29.1 | 29.3 | 29.0 | 28.9 | 30.8 |

| Minimum Temperature (°C) | 10.3 | 11.6 | 13.6 | 15.8 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 15.9 | 15.9 | 16.1 | 14.5 | 12.3 | 11.0 | 14.2 |

| Precipitation (mm) | 2.4 | 4.6 | 17.6 | 47.3 | 97.9 | 188.3 | 118.6 | 131.8 | 163.6 | 63.1 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 853.3 |

| Location | DLI (mol m−2 d−1) | Temperature (°C) | Relative Humidity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| East | 29.33 ± 0.83 b | 28.26 ± 0.38 b | 30.31 ± 1.36 a |

| West | 38.81 ± 0.77 a | 31.19 ± 0.26 a | 31.52 ± 1.45 a |

| Category | Parameter | Quantitative Value | Condition/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reproductive Cycle | Anthesis development | 45–65 days | From bud appearance to full opening (in situ) |

| Fruit set duration | 60–75 days | From petal fall to “jarrito” stage (immature fruit) | |

| Post-Harvest Dynamics | Biomass loss rate | 94% reduction | Total weight loss (Fresh to Dry) |

| Drying time (Traditional) | 5 days | Shade drying on petate/metal | |

| Drying time (Accelerated) | 2 days | Direct solar exposure | |

| Productive Yield | Annual harvest estimate | 10–12 kg (dry weight) | Mature trees (>50 years) with supplementary irrigation |

| Category | Indicator/Practice | Consensus Result |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Tenure | Access Regime | 100% Domestic/Private (Backyards). No communal forest extraction reported. |

| Gender Role | Women control harvest, processing, and sale. Men assist in pruning and planting. | |

| Water Management | Irrigation Frequency (Dry Season) | Daily (Trees > 50 years); 2–3 times/week (Young trees). |

| Water Source | Potable municipal network and private wells. | |

| Post-harvest Handling | Harvesting Technique | Manual collection with “carrizo” (reed) poles to avoid damaging buds. |

| Drying Method | Dual practice: Shade drying (5 days) for quality vs. Sun drying on metal (2 days) for speed. | |

| Ecological Perception | Threat Identification | 90% identify “Heat/Drought” as the main threat. |

| Replacement Strategy | 60% have planted replacement saplings but report high mortality rates. | |

| Economic Value | Market Price | High value: ~91.48 USD/kg (Dry) driving intensive care. |

| Rainy Season Constraint | Immediate harvest is required to prevent fungal decay/staining. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ortiz-Hernández, Y.D.; Acevedo-Ortiz, M.A.; Lugo-Espinosa, G.; Ortiz-Hernández, F.E.; García-Sánchez, E.; Velasco-Pérez, S. Eco-Physiological Vulnerability of Quararibea funebris in Peri-Urban Landscapes: Integrating Gender and Nature-Based Solutions in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1630. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031630

Ortiz-Hernández YD, Acevedo-Ortiz MA, Lugo-Espinosa G, Ortiz-Hernández FE, García-Sánchez E, Velasco-Pérez S. Eco-Physiological Vulnerability of Quararibea funebris in Peri-Urban Landscapes: Integrating Gender and Nature-Based Solutions in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1630. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031630

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtiz-Hernández, Yolanda Donají, Marco Aurelio Acevedo-Ortiz, Gema Lugo-Espinosa, Fernando Elí Ortiz-Hernández, Edgar García-Sánchez, and Salatiel Velasco-Pérez. 2026. "Eco-Physiological Vulnerability of Quararibea funebris in Peri-Urban Landscapes: Integrating Gender and Nature-Based Solutions in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1630. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031630

APA StyleOrtiz-Hernández, Y. D., Acevedo-Ortiz, M. A., Lugo-Espinosa, G., Ortiz-Hernández, F. E., García-Sánchez, E., & Velasco-Pérez, S. (2026). Eco-Physiological Vulnerability of Quararibea funebris in Peri-Urban Landscapes: Integrating Gender and Nature-Based Solutions in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico. Sustainability, 18(3), 1630. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031630