Urban Villages as Hotspots of Road-Deposited Sediment: Implications for Sustainable Urban Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

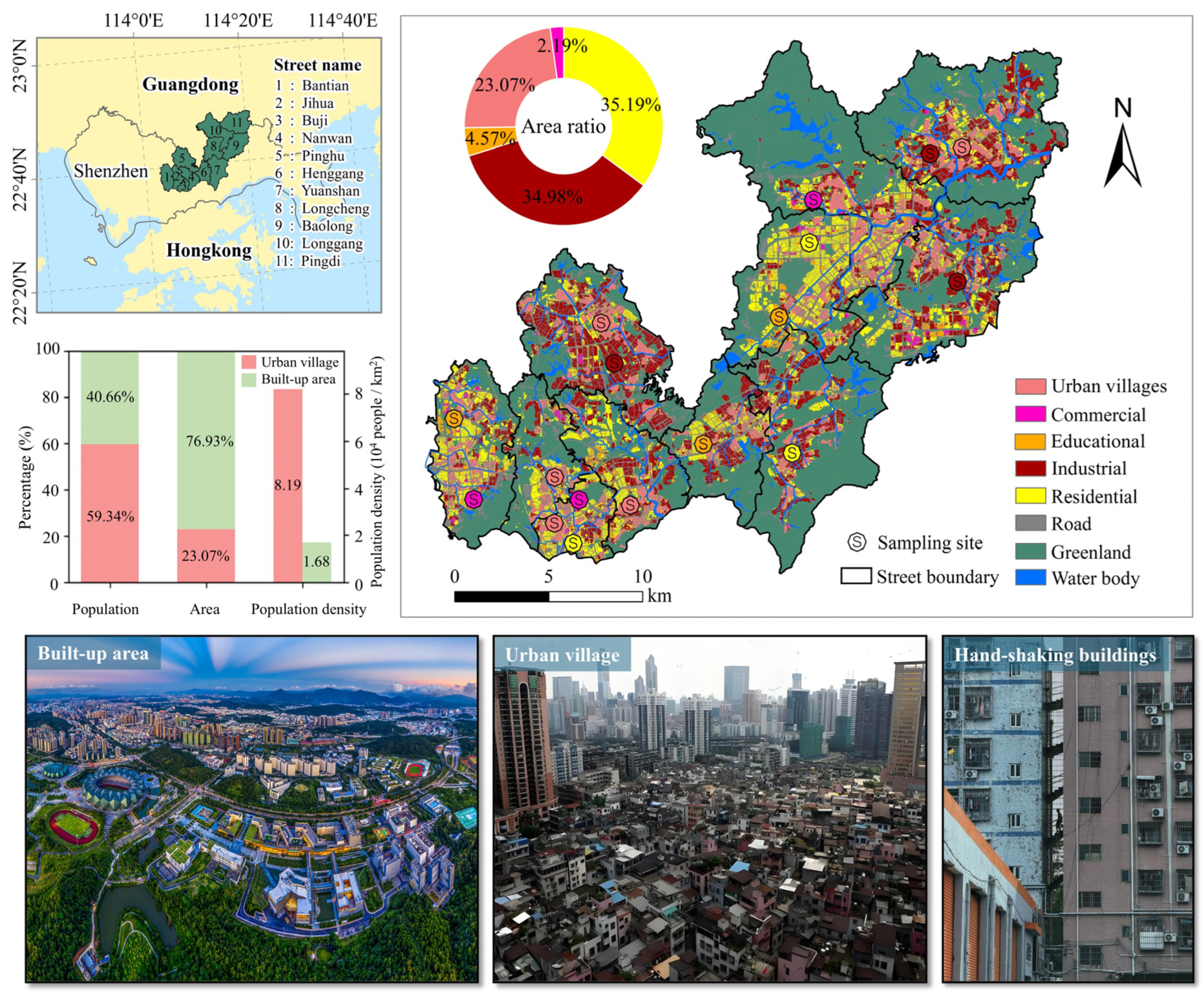

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Processing

2.2.1. RDS Sampling and Grouping

- Sampling design: Referring to Peking University’s Dataset of Major Urban Landscapes in China (http://geodata.pku.edu.cn, accessed on 2 January 2025), the study area was divided into 5 major functional zones: urban villages (UVs), commercial zone (CZ), educational zone (EZ), residential zone (RZ), and industrial zone (IZ) (Figure 1). On this basis, 17 sampling sites were set up in Longgang District, covering all functional zones. These involved sites were located at least 100 m away from garbage dumps or sewage outfalls to minimize anomalous pollution inputs, and sanitation frequencies of different functional zones are shown in Table S2.

- Sampling method: The sampling campaign was conducted in April 2025, a critical transition period representing the late dry season in Shenzhen. This timing is highly representative as it follows a prolonged antecedent dry period, allowing pollutants to undergo long-term accumulation and potentially reach a state of dynamic equilibrium or peak load before the onset of the wet season. In addition, RDS sampling was mainly conducted within 1 m of the roadside, and prior to RDS sampling, communication was carried out with the sanitation department to demarcate a sampling area free from artificial cleaning interference for each site (as indicated by the red markings in Figure S1). To preserve the particle size characteristics of accumulated RDS as accurately as possible, this study used a vacuum cleaner (Shark IF202CN) to collect RDS. Sampling lasted approximately two weeks (daily collection in the first week and once every two days thereafter), and RDS accumulation was determined to reach equilibrium when its increment was less than 5% for three consecutive days.

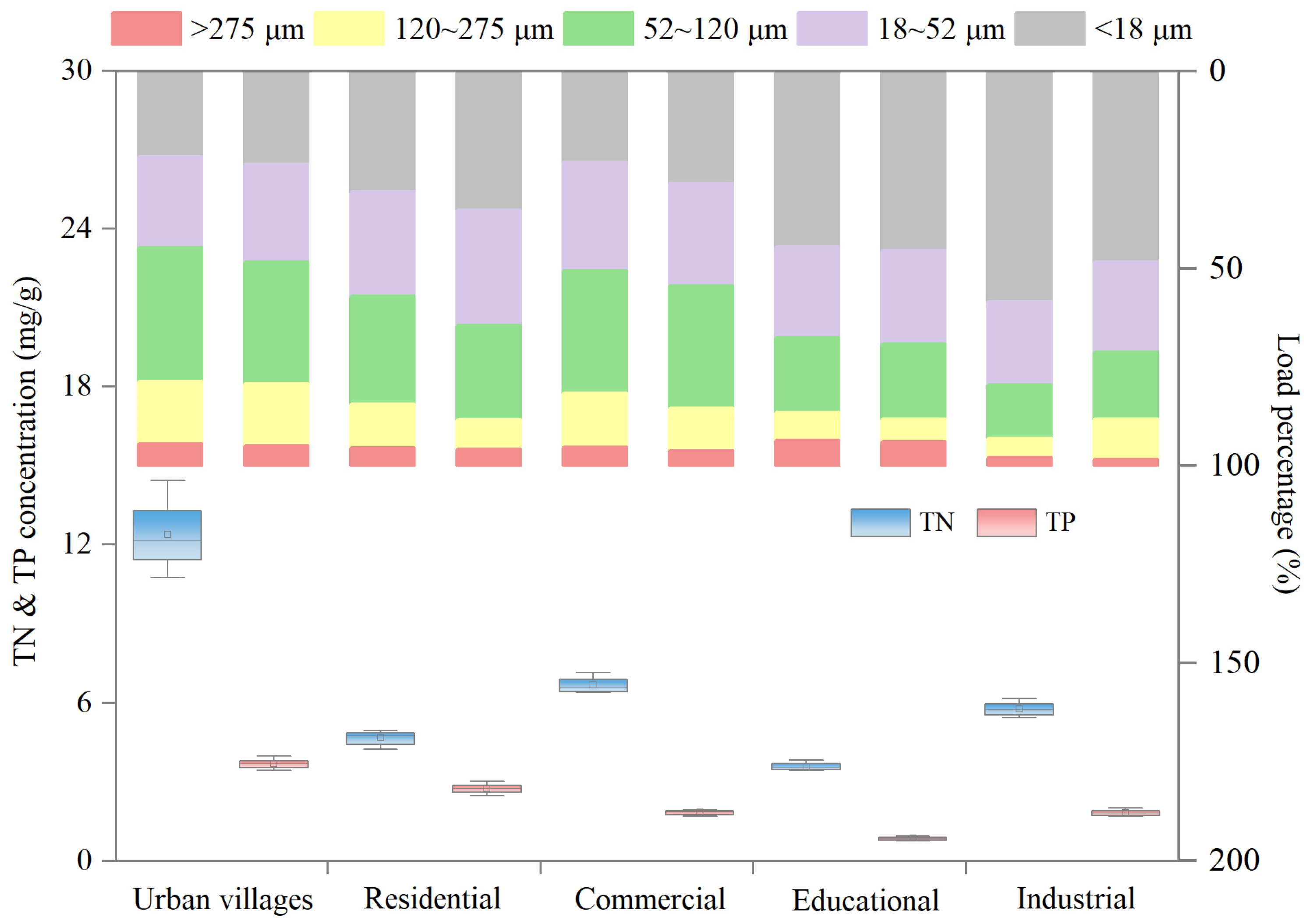

- Sample processing: Samples were dried, weighed after removing impurities through a 2 mm sieve, and their particle size distribution (0.02–2000 μm) was determined using a laser particle size analyzer (Master2000, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). Subsequently, RDS was evenly sieved into 5 particle size groups based on particle size distribution characteristics (0~d20, d20~d40, d40~d60, d60~d80, >d80), with the purpose of ensuring each fraction had equal mass. Incorporating the actual particle size detection results, the specific particle size ranges for the final grouping were confirmed as <18 μm, 18~52 μm, 52~120 μm, 120~275 μm, and >275 μm. For each RDS group, the total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) contents were measured using alkaline potassium persulfate digestion followed by spectrophotometry [31]. All chemical analyses were performed at the Water Environment Laboratory, Dangtu Scientific Experiment Base, Nanjing Hydraulic Research Institute (Ma’anshan, China). To ensure data reliability, strict quality assurance and quality control procedures were implemented. Replicate samples (n = 3) were analyzed for the total samples, yielding relative standard deviations (RSD) of less than 5% for both TN and TP. Procedural blanks indicated no detectable interference. Analytical accuracy was verified using standard reference materials (GSS series) and spiked samples, with recovery rates ranging from 90% to 110%. The method detection limits (MDL) were 10 mg/kg for TN and 5 mg/kg for TP.

2.2.2. Environmental Data Collection

2.3. Calculation of Pollution Intensity

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

- Mean particle size (Mz): Represents the central tendency of the RDS particle size distribution, reflecting the overall “coarseness or fineness” of the dust—for example, smaller Mz values indicate that RDS is dominated by fine particles, which are more likely to adsorb pollutants and have stronger mobility.

- Sorting coefficient (Sd): Characterizes the uniformity of particle size distribution; Sd < 1 indicates well-sorted dust (particle sizes are relatively concentrated), while Sd > 2 means poorly sorted dust (particle sizes vary widely), which is often associated with multiple sediment sources.

- Kurtosis (Ku): Describes the “sharpness” of the particle size distribution curve; Ku > 1.1 indicates a leptokurtic distribution (the curve has a sharp peak, meaning a high proportion of particles in the dominant size range), while Ku < 0.9 indicates a platykurtic distribution (the curve is flat, meaning particles are more evenly distributed across multiple size ranges).

3. Results

3.1. Accumulation Characteristics of RDS in Different Functional Zones

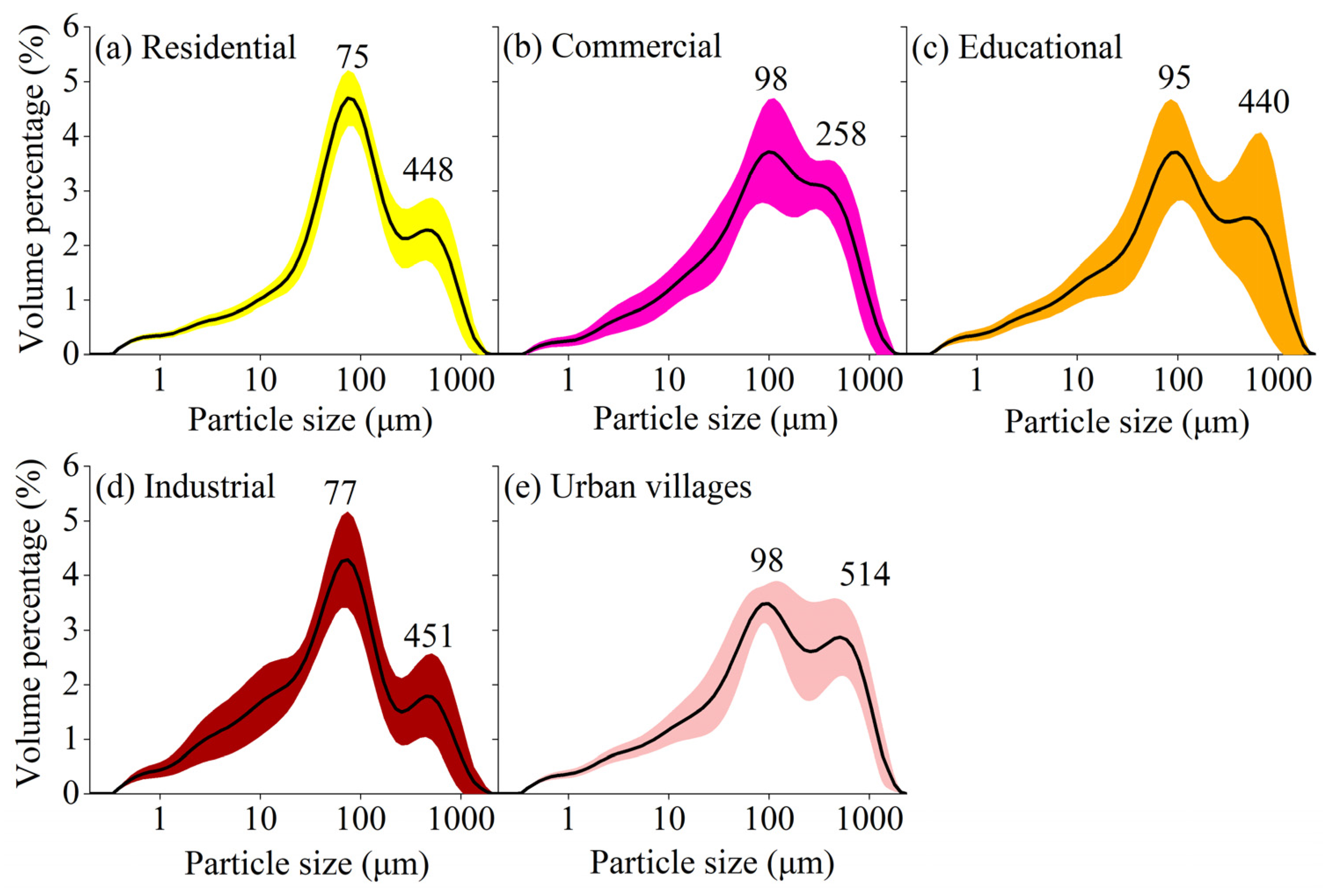

3.2. Particle Size Characteristics of RDS in Different Functional Zones

3.3. Spatial and Temporal Characteristics of N and P Pollution Intensity

3.4. Correlation Between RDS Pollution and Multiple Driving Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Pollutant Input–Output Imbalance in Urban Villages

4.2. Cross-Media Pollutant Transfer at the Air–Road Interface

4.3. Implications for Urban Planning Under Terrain Constraints

4.4. Advantages and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPS | Non-point source |

| RDS | Road-deposited sediment |

| UVs | Urban villages |

| CZ | Commercial zone |

| EZ | Educational zone |

| RZ | Residential zone |

| IZ | Industrial zone |

References

- Zeng, J.; Huang, G.; Luo, H.; Mai, Y.; Wu, H. First flush of non-point source pollution and hydrological effects of LID in a Guangzhou community. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Q.; Liu, Q.; Yue, W.; Xu, C.; Su, M. Optimal design of low impact development at a community scale considering urban non-point source pollution management under uncertainty. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, Q.Q.; Ding, H.J.; Song, Y.Q.; Pan, Q.X.; Deng, H.P.; Zeng, E.Y. Differences of microplastics and nanoplastics in urban waters: Environmental behaviors, hazards, and removal. Water Res. 2024, 260, 121895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Ding, C.; Hua, P. Traffic contribution to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in road dust: A source apportionment analysis under different antecedent dry-weather periods. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.Y.; Cui, D.L.; Yang, Z.Y.; Ma, J.Y.; Liu, J.J.; Yu, Y.X.; Huang, X.F.; Xiang, P. Health risk assessment of heavy metal(loid)s in road dust via dermal exposure pathway from a low latitude plateau provincial capital city: The importance of toxicological verification. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Tian, Z.; Zou, G.; Du, L.; Guo, X. Potential Risk Identification of Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution: A Case Study of Yichang City, Hubei Province. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.H.; Park, Y. Build-up and wash-off behavior of heavy metals in road-deposited sediments on asphalt surfaces: A grain-size-resolved modeling approach for urban runoff risk. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, V.; Krishnamurthy, R.R.; Bhuvaneswari, M.; Deepika, R.; Nathan, C.S.; Bharath, K.M.; Magesh, N.S.; Kalaivanan, R.; Ayyamperumal, R. Hazardous trace elemental contamination in urban river sediments: Distribution, source identification, and Environmental impacts. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrouz, M.S.; Sample, D.J.; Kisila, O.B.; Harrison, M.; Yazdi, M.N.; Garna, R.K. Parameterization of nutrients and sediment build-up/wash-off processes for simulating stormwater quality from specific land uses. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shi, A.; Zhang, X. Particle size distribution and characteristics of heavy metals in road-deposited sediments from Beijing Olympic Park. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 32, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, M.; Huang, T.; Tu, N.; Li, B. Particle size distribution and pollutant dissolution characteristics of road-deposited sediment in different land-use districts: A case study of Beijing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 38497–38505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hua, P.; Krebs, P. Influences of land use and antecedent dry-weather period on pollution level and ecological risk of heavy metals in road-deposited sediment. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 228, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.F.; Yu, J.; Gong, Y.; Wu, L.L.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Gao, R.; Liu, W.W. Pollution characteristics, sources and health risk of metals in urban dust from different functional areas in Nanjing, China. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 11607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dong, J.; Hong, N.; Tan, Q. Understanding phosphorus fractions and influential factors on urban road deposited sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 170624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, X. Risk assessment of metals in road-deposited sediment along an urban–rural gradient. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 174, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Chen, Y.S.; Dong, J.W.; Hong, N.; Tan, Q. Characterizing nitrogen deposited on urban road surfaces: Implication for stormwater runoff pollution control. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 952, 175692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhu, D.Z.; Loewen, M.R.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; van Duin, B.; Chen, L.; Mahmood, K. Particle size distribution of total suspended sediments in urban stormwater runoff: Effect of land uses, precipitation conditions, and seasonal variations. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.L.; Wu, L.; Ruan, B.N.; Xu, L.J.; Liu, S.; Guo, Z.J. Can the best management practices resist the combined effects of climate and land-use changes on non-point source pollution control? Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.P.; Cheng, G.; Xu, S.J.; Bi, Y.L.; Jiang, C.C.; Ma, S.L.; Wang, D.S.; Zhuang, X.L. Temporal and spatial changes of water quality in intensively developed urban rivers and water environment improvement: A case study of the Longgang River in Shenzhen, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 99454–99472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Zhang, Y.J.; Bing, H.J.; Peng, J.; Dong, F.F.; Gao, J.F.; Arhonditsis, G.B. Characterizing the river water quality in China: Recent progress and on-going challenges. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.P.; Zhou, Y.X.; Wang, H.Y.; Jiang, H.Z.; Yue, Z.W.; Zheng, K.; Wu, B.; Banahene, P. Characterization and sources apportionment of overflow pollution in urban separate stormwater systems inappropriately connected with sewage. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, P. Risk Assessment of Dynamic Diffusion of Urban Non-Point Source Pollution Under Extreme Rainfall. Toxics 2025, 13, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.X.; Xu, J.; Yin, H.L.; Jin, W.; Li, H.Z.; He, Z. Urban river pollution control in developing countries. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Hu, W.; Xia, X. Reshaping urban governance: Vertical adaptation of the integrated LRF model through urban village renewal in Hangzhou, China. J. Urban Manag. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Lai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, R.; Tang, X.; Li, X.; Ma, D.; Guo, R. Public attitudes toward state-led urban village rehabilitation in Shenzhen, China. Habitat Int. 2025, 160, 103404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations, U. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jnawali, S.S.; McBroom, M.; Zhang, Y.; Stafford, K.; Wang, Z.; Creech, D.; Cheng, Z. Effectiveness of Rain Gardens for Managing Non-Point Source Pollution from Urban Surface Storm Water Runoff in Eastern Texas, USA. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, A.; Oyebode, O.; Satterthwaite, D.; Chen, Y.-F.; Ndugwa, R.; Sartori, J.; Mberu, B.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Haregu, T.; Watson, S.I. The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. Lancet 2016, 389, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, P.; Sliuzas, R.; Geertman, S. The development and redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y. Evaluation of Renovation Projects of Urban Villages and Historic Buildings in Shenzhen. Commun. Humanit. Res. 2023, 6, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, D.; Martens, D.; Kingery, W. Nature of clay-humic complexes in an agricultural soil: I. Chemical, biochemical, and spectroscopic analyses. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, L. Dry deposition velocity of PM2.5 ammonium sulfate particles to a Norway spruce forest on the basis of S- and N-balance estimations. Atmos. Environ. 2003, 37, 4419–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, F.; Abbasi, Y.; Sohrabi, T.; Mirhashemi, S.H. Investigation of heavy metalloid pollutants in the south of Tehran using kriging method and HYDRUS model. Geosci. Lett. 2022, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blott, S.J.; Pye, K. GRADISTAT: A grain size distribution and statistics package for the analysis of unconsolidated sediments. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2001, 26, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.Q.; Yu, T.; Leng, W.J.; Zhang, X. Distribution and Fractal Characteristics of Outdoor Particles in High-Rise Buildings Based on Fractal Theory. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.E.; Jenks, R.; Auborg, D. An assessment of the availability of pollutant constituents on road surfaces. Sci. Total Environ. 1998, 209, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.H.; Yuan, Q.; Cai, H.L. Unravelling urban governance challenges: Objective assessment and expert insights on livability in Longgang District, Shenzhen. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.; Dickin, S.; Rosemarin, A. Towards “Sustainable” Sanitation: Challenges and Opportunities in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaze, J.; Chiew, F.H. Experimental study of pollutant accumulation on an urban road surface. Urban Water 2002, 4, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egodawatta, P.; Thomas, E.; Goonetilleke, A. Mathematical interpretation of pollutant wash-off from urban road surfaces using simulated rainfall. Water Res. 2007, 41, 3025–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botturi, A.; Ozbayram, E.G.; Tondera, K.; Gilbert, N.; Rouault, P.; Caradot, N.; Gutierrez, O.; Daneshgar, S.; Frison, N.; Akyol, Ç.; et al. Combined sewer overflows: A critical review on best practice and innovative solutions to mitigate impacts on environment and human health. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 51, 1585–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Wu, D.S.; Kuang, Q.; Wu, Q.Q.; Wei, L.S.; Huang, H.; Zhou, F.B. Strategy and consequence of intermittent segmented pulse-jet cleaning for long-box-shaped filter dust collector. Powder Technol. 2018, 340, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.Q.; Li, X.H.; Xing, Z.Q.; Kuang, Q.; Li, J.L.; Huang, S.; Huang, H.; Ma, Z.F.; Wu, D.S. Inhibition of Dust Re-Deposition for Filter Cleaning Using a Multi-Pulsing Jet. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, J.; Egodawatta, P.; Ayoko, G.A.; Goonetilleke, A. Atmospheric deposition as a source of heavy metals in urban stormwater. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 68, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardoulakis, S.; Fisher, B.E.; Pericleous, K.; Gonzalez-Flesca, N. Modelling air quality in street canyons: A review. Atmos. Environ. 2003, 37, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Yu, C.W. Impact factors on airflow and pollutant dispersion in urban street canyons and comprehensive simulations: A review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2020, 6, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. Street design and urban canopy layer climate. Energy Build. 1988, 11, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-X.; Liu, C.-H.; Leung, D.Y.; Lam, K.M. Recent progress in CFD modelling of wind field and pollutant transport in street canyons. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 5640–5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; You, Z.J.; Idrees, M.B.; Ali, S.; Buttar, N.A. Exploring urban runoff complexity: Road-deposited sediment wash-off mechanisms and dynamics of constraints. J. Hydroinform. 2024, 26, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Xie, W.; Li, X.; Yin, C. Influence of urban surface roughness on build-up and wash-off dynamics of road-deposited sediment. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Luan, B.; Zhang, T.T.; Liang, D.F.; Zhang, C. Experimental study of sediment wash-off process over urban road and its dependence on particle size distribution. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 86, 2732–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.K.; Guo, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W.J. Spatial and temporal evolution of the “source-sink” risk pattern of NPS pollution in the upper reaches of Erhai Lake Basin under land use changes in 2005–2020. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Khaledi Darvishan, A.; Bahramifar, N.; Alavi, S.J. Spatio-temporal suspended sediment fingerprinting under different land management practices. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2023, 38, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Li, C.L.; Qiao, J.M.; Hu, Y.M.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, J.B.; Slater, L. Meta-Analysis of Urban Non-Point Source Pollution From Road and Roof Runoff Across China. Earth Future 2025, 13, e2024EF005296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saby, L.; Herbst, R.S.; Goodall, J.L.; Nelson, J.D.; Culver, T.B.; Stephens, E.; Marquis, C.M.; Band, L.E. Assessing and improving the outcomes of nonpoint source water quality trading policies in urban areas: A case study in Virginia. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, G.W.C.; Zhang, X.Y.; Fu, Y.J.; Wang, J.Y.; Meng, X.Y.; Gao, S.H.; Ma, Y.K.; Shen, Z.Y.; Chen, L. Changes in the effectiveness of low impact development practices and their role in optimal design. J. Hydrol. 2025, 660, 133505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Dian, Y.; Guo, Z.Q.; Yao, C.H.; Wu, X.F. A Functional Zoning Method in Rural Landscape Based on High-Resolution Satellite Imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.A.; Heiden, U.; Lakes, T.; Feilhauer, H. Are urban material gradients transferable between areas? Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 100, 102332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, S.; Chatterjee, U.; Bhattacharya, S.; Paul, S.; Bindajam, A.A.; Mallick, J.; Abdo, H.G. Peri-urban dynamics: Assessing expansion patterns and influencing factors. Ecol. Process. 2024, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, A.A.; Rustiadi, E.; Fauzi, A.; Pravitasari, A.E.; Saizen, I.; Zenka, J. Understanding Industrial Land Development on Rural-Urban Land Transformation of Jakarta Megacity’s Outer Suburb. Land 2022, 11, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Variable Name | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-economic | population (Pop), population density (PD), and gross domestic product (GDP, billion CNY) | Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Longgang District, annual (2020–2023) |

| Geo-environmental | Functional types (UVs, CZ, EZ, RZ, IZ), construction land area (CLA, m2), proportion of construction land (PCL, %) | Geographic Data Sharing Infrastructure, College of Urban and Environmental Science, Peking University, http://geodata.pku.edu.cn (accessed on 2 January 2025) |

| Terrain slope (TS, °) | Derived from 30 m DEM data, Geospatial Data Cloud, https://www.gscloud.cn/ (accessed on 6 October 2025) | |

| Precipitation | Yearly precipitation (Prcp, mm) | China Meteorological Data Network, http://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 6 October 2025) |

| Dry deposition | Dry deposition flux (DDF, kg·day−1) | Shenzhen Ecological Environment Bureau, https://meeb.sz.gov.cn/, calculated using PM2.5 data |

| Functional Type | Particle Size Distribution (%) | Granularity Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤4 μm | 4~63 μm | 63~125 μm | ≤l00 μm | Mz (μm) | Sd | Ku | D | |

| UVs | 5.72 | 35.41 | 20.63 | 55.07 | 158.97 | 0.16 | 1.35 | 2.29 |

| RZ | 7.01 | 35.1 | 22.07 | 57.53 | 152.93 | 0.2 | 1.71 | 2.30 |

| CZ | 5.36 | 30.85 | 20.78 | 49.94 | 157.71 | 0.18 | 1.38 | 2.31 |

| EZ | 8.43 | 38.02 | 19.75 | 60.01 | 145.06 | 0.19 | 1.83 | 2.33 |

| IZ | 11.48 | 46.41 | 18.68 | 71.26 | 85.51 | 0.14 | 2.25 | 2.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, M.; Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y. Urban Villages as Hotspots of Road-Deposited Sediment: Implications for Sustainable Urban Management. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031543

He M, Chen C, Zhang J, Ma J, Liu Y. Urban Villages as Hotspots of Road-Deposited Sediment: Implications for Sustainable Urban Management. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031543

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Mengnan, Cheng Chen, Jianmin Zhang, Jinge Ma, and Yang Liu. 2026. "Urban Villages as Hotspots of Road-Deposited Sediment: Implications for Sustainable Urban Management" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031543

APA StyleHe, M., Chen, C., Zhang, J., Ma, J., & Liu, Y. (2026). Urban Villages as Hotspots of Road-Deposited Sediment: Implications for Sustainable Urban Management. Sustainability, 18(3), 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031543