The Impact Mechanism and Effect Evaluation of the National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone on the Resilience of Manufacturing Enterprises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

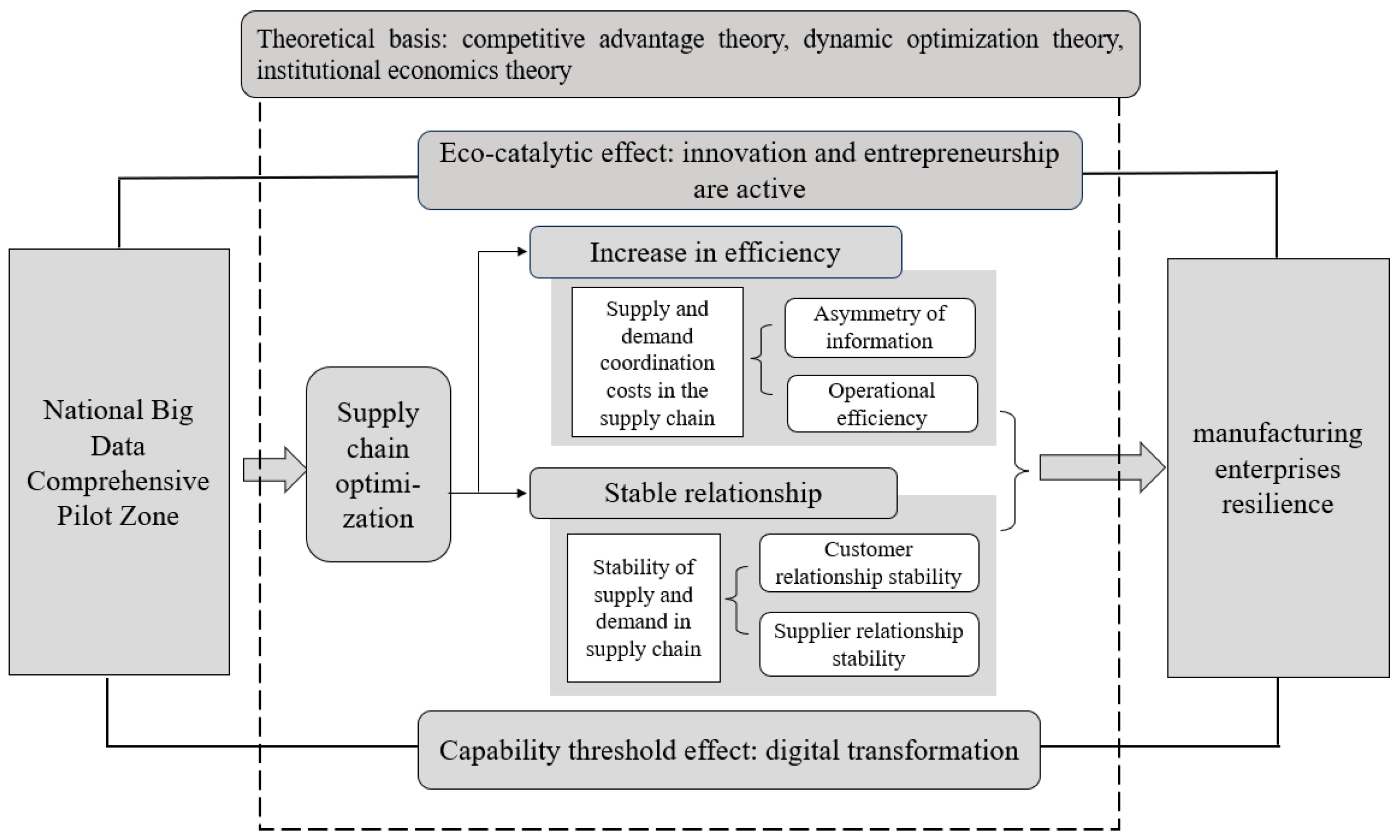

3. Theoretical Hypotheses

3.1. The Impact of NBDPZ on the Manufacturing Enterprises’ Resilience

3.2. The Moderating Effect of Enterprise Digital Transformation

3.3. The Moderating Effect of Regional Innovation and Entrepreneurship Activity

3.4. Channel Path Effect of Supply Chain Optimization

4. Data and Empirical Strategy

4.1. Data

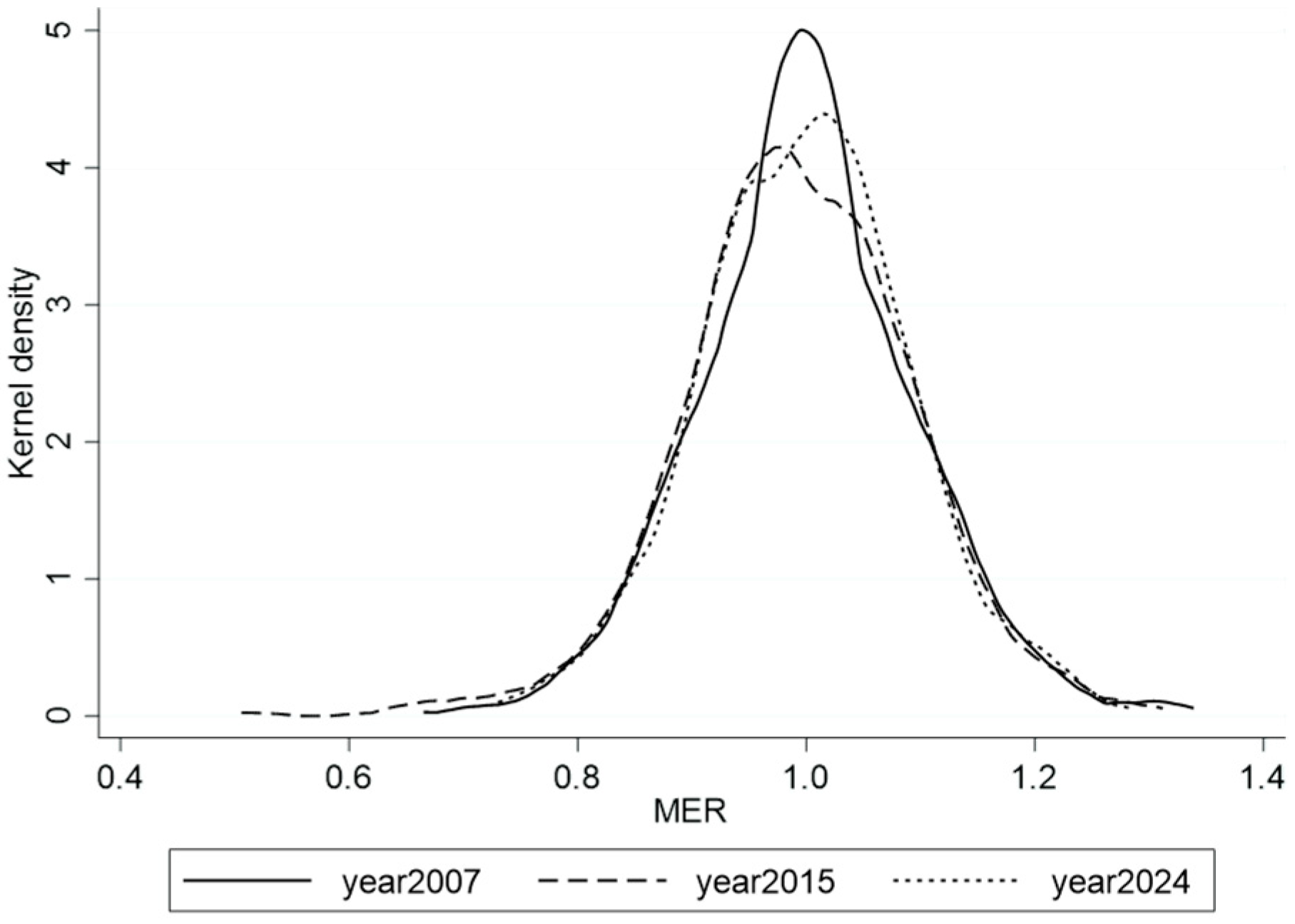

4.1.1. Variable Explained

4.1.2. Core Explanatory Variable

4.1.3. Control Variable

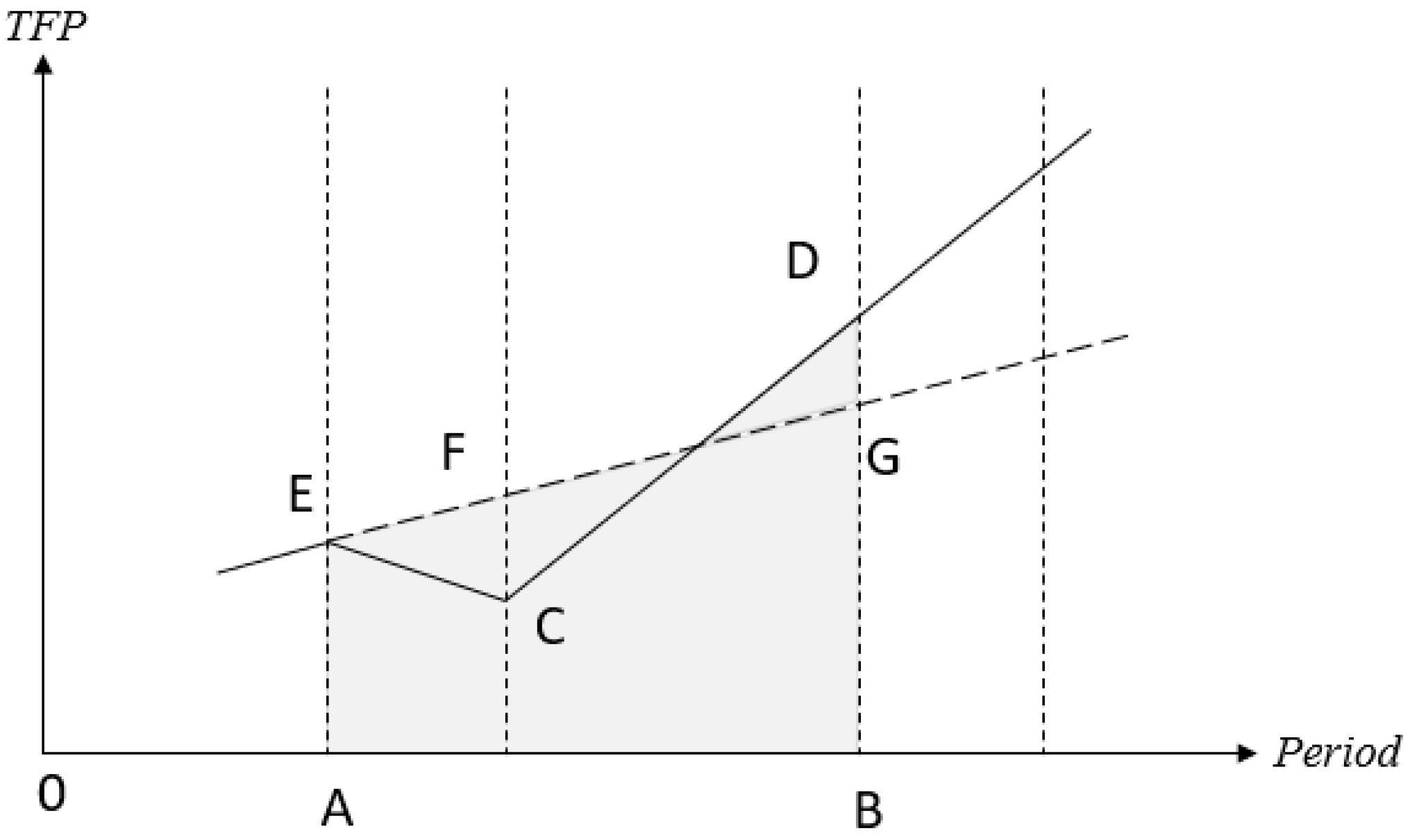

4.2. Empirical Strategy

5. Main Results Analysis

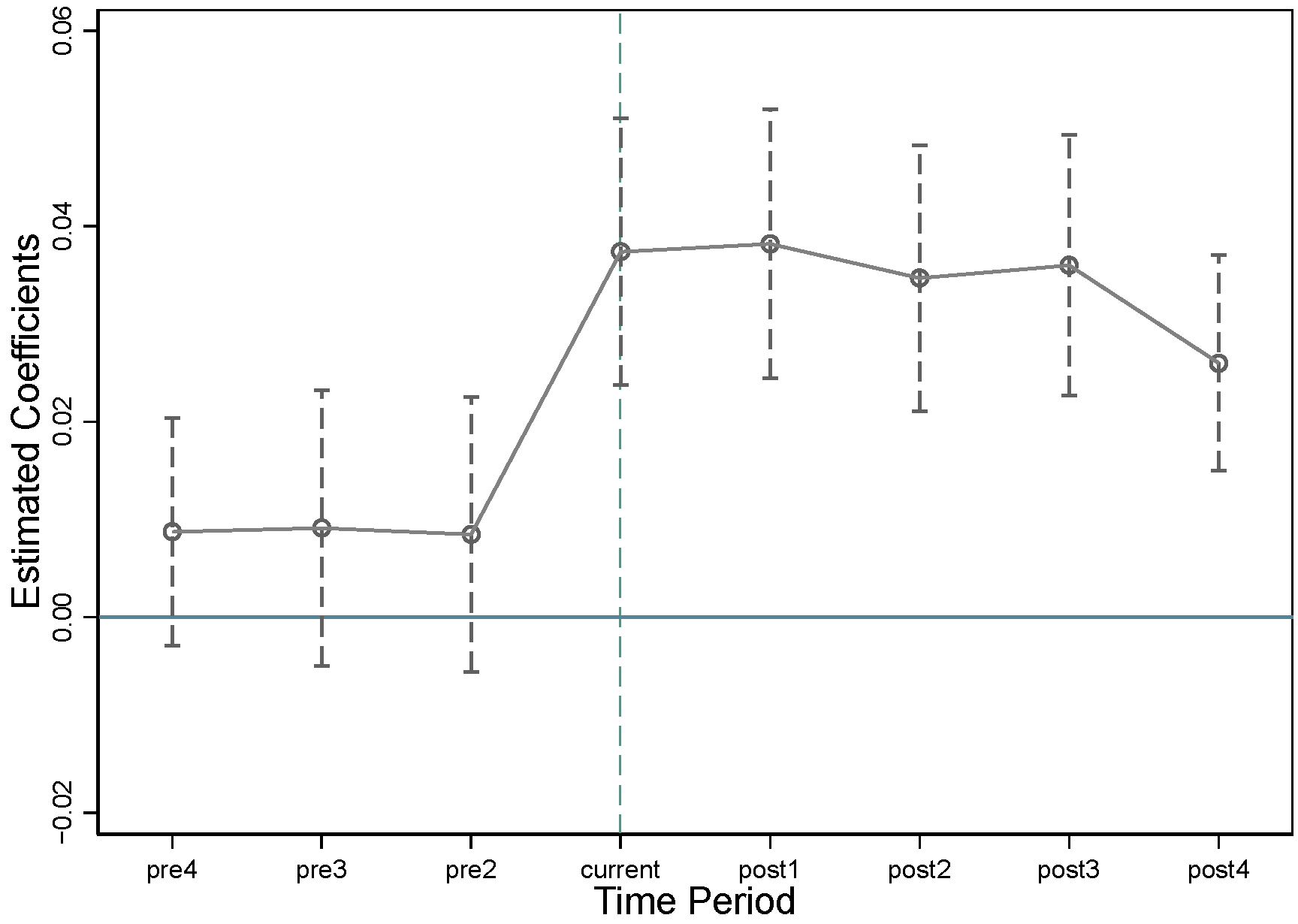

5.1. Parallel Trend Test

5.2. Benchmark Regression

5.3. Robustness Test

5.3.1. PSM-DID

5.3.2. Exclude the Influence of Similar Policies

5.3.3. Exclude the Impact of External Event Shocks

5.3.4. Endogeneity Test

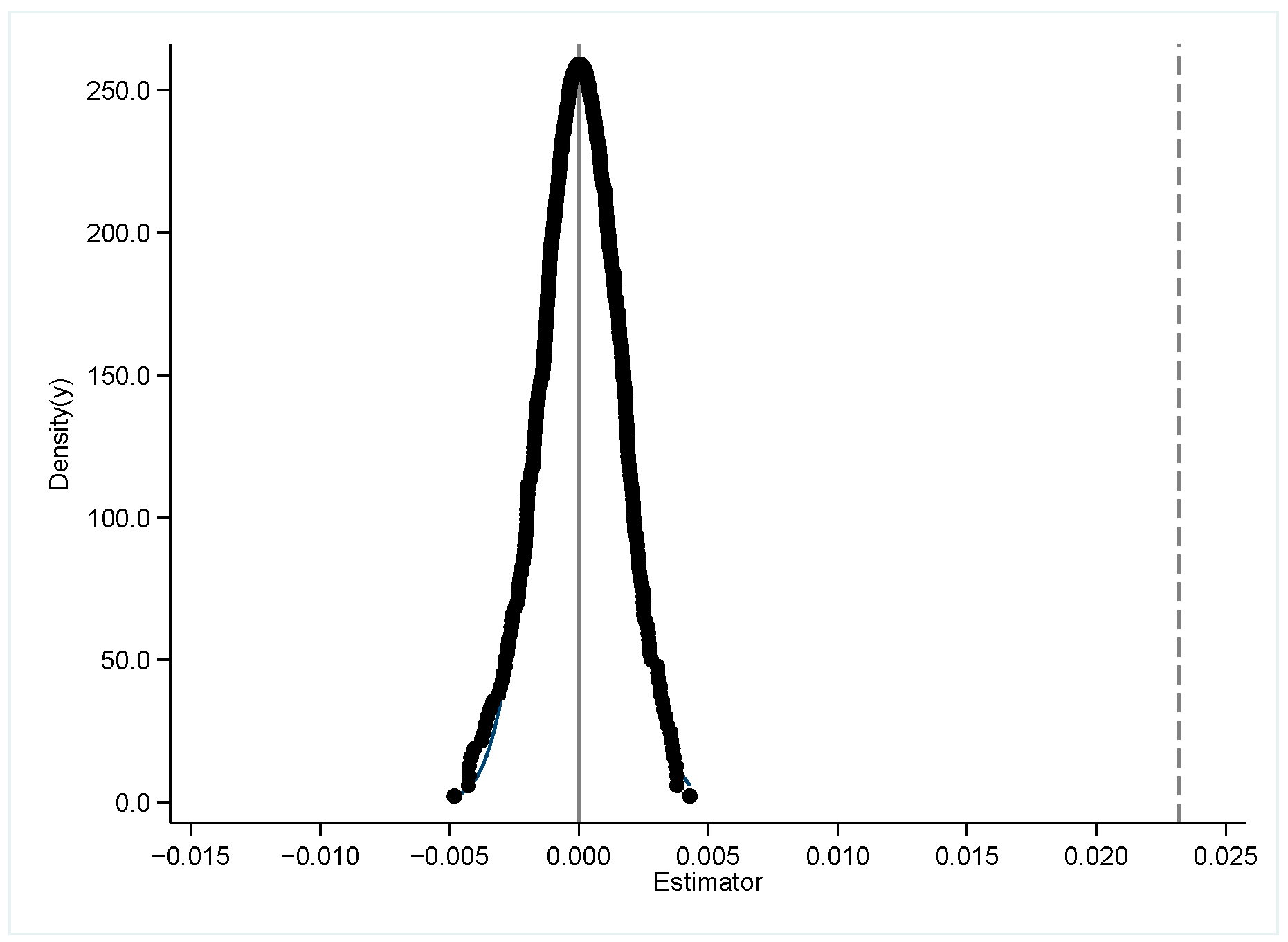

5.3.5. Placebo Test

5.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.4.1. Region and City Heterogeneity

5.4.2. Industry Heterogeneity

5.4.3. Enterprise Heterogeneity

6. Mechanism Analysis

6.1. Moderating Effect Analysis

6.1.1. Moderating Effect Model

6.1.2. Moderating Variable

6.1.3. Analysis of Moderating Effect Results

6.2. Channel Path Analysis

6.2.1. Channel Effect Model

6.2.2. Variable of Channel

6.2.3. Analysis of Channel Effect Results

6.3. Further Analysis: The Impact of the “Pan-National” Comprehensive Big Data Pilot Zone

7. Discussion

7.1. Dialogue with Existing Literature

7.2. Comparison with International Studies

8. Conclusions and Implications

8.1. Conclusions

8.2. Policy Implications

8.3. Managerial Implications

8.4. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | English Meaning |

| NBDPZ | China’s National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone |

| TFP | Total Factor Productivity |

| MER | manufacturing enterprises’ resilience |

| PSM-DID | Propensity Score Matching Difference-in-Differences |

| sz | digital transformation |

| cx | innovation and entrepreneurship activity |

| fxcx | attracting venture capital |

| xjcx | number of newly established enterprises |

| sbcx | number of trademark registrations |

References

- Gallopín, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, R.; Poler, R. Enterprise resilience assessment—A quantitative approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, D.; Bueno, A.; Godinho Filho, M.; Latan, H.; Ganga, G.M.D.; Frank, A.G.; Jabbour, C.J.C. The role of Industry 4.0 in developing resilience for manufacturing companies during COVID-19. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 256, 108728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Mao, N.; Lan, F.; Wang, L. Policy Empowerment, Digital Ecosystem and Enterprise Digital Transformation: A Quasi Natural Experiment Based on the National Big Data Comprehensive Experimental Zone. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 9, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhou, Y. Development of Digital Economy and Regional Total Factor Productivity: An Analysis Based on National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 47, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xu, H.; Jiang, C.; Deng, S.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z. Has the Digital Economy Improved the Urban Land Green Use Efficiency? Evidence from the National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone Policy. Land 2024, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, N. Digital Technology Development, Industries-Universities-Research Collaboration and Enterprise Innovation Capability: An Analysis Based on National Big Data Comprehensive Experimental Zone. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2022, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, X. Big data development and total factor productivity of enterprises:empirical analysis based on the national big data comprehensive pilot zone. Ind. Econ. Res. 2023, 2, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zhao, C. Big Data Policy Governing Enterprises′ “Shift from Real to Virtual”: A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the National-Level Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone. East China Econ. Manag. 2024, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z. How does the Development of Digital Economy Affect Manufacturing Enterprises to “Get Rid of Virtual Reality”: Evidence from National Big Data Comprehensive Test Area? Mod. Econ. Res. 2022, 7, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Hammond, J.; Obermeyer, W.; Raman, A. Configuring a supply chain to reduce the cost of demand uncertainty. Prod. Oper. Manag. 1997, 6, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H. Specialized supplier networks as a source of competitive advantage: Evidence from the auto industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost, F.; Fawcett, T. Data science and its relationship to big data and data-driven decision making. Big Data 2013, 1, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Pan, J.; Liu, S.; Feng, T. Impact of digital capability on firm resilience: The moderating role of coopetition behavior. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 2167–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiapa, M.; Batsiolas, I. Firm resilience in regions of Eastern Europe during the period 2007–2011. Post-Communist Econ. 2019, 31, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Song, X.; Guo, X. The Impact of Investor Protection on Corporate Resilience. Bus. Manag. J. 2020, 42, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlenbrach, R.; Rageth, K.; Stulz, R.M. How valuable is financial flexibility when revenue stops? Evidence from the COVID-19 crisis. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2021, 34, 5474–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yu, W.; Zhao, J.L. How signaling and search costs affect information asymmetry in P2P lending: The economics of big data. Financ. Innov. 2015, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y. Big data analysis adaptation and enterprises’ competitive advantages: The perspective of dynamic capability and resource-based theories. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumar, A.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Dutta, D.K. The potential link between corporate innovations and corporate competitiveness: Evidence from IT firms in the UK. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrogio, G.; Filice, L.; Longo, F.; Padovano, A. Workforce and supply chain disruption as a digital and technological innovation opportunity for resilient manufacturing systems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Deng, S. The Impact of Digital Transformation on Firm Resilience: Evidence From the COVID-19 Pandemic. Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Guo, H.; Ding, J. Digital Transformation Rhythm and Firm Performance: Based on Absorptive Capacity Theory. J. Syst. Manag. 2025, 34, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Liu, J.; Huang, H. Research on the Impact of New Infrastructure Construction on Regional Innovation and Entrepreneurship Activity. Chin. J. Manag. 2024, 21, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Li, P.; Ou, Z. Intellectual Property Protection, Digital Economy and Regional Entrepreneurial Activity. China Soft Sci. 2021, 10, 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Piplani, R.; Fu, Y. A coordination framework for supply chain inventory alignment. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2005, 16, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beveren, I. Total factor productivity estimation: A practical review. J. Econ. Surv. 2012, 26, 98–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Zhu, Z. Exploratory Innovation and Firm Resilience—Evidence from NEEQ Listed Companies. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 45, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Dubey, R.; Wamba, S.F.; Childe, S.J.; Hazen, B.; Akter, S. Big data and predictive analytics for supply chain and organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rubin, D.B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983, 70, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P. Increasing returns and economic geography. J. Political Econ. 1991, 99, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Suo, Q.; Yang, H. Which Economic Gap Is Bigger in China? North-South or East-West. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2021, 38, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The foundations of enterprise performance: Dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenstein, H. Allocative efficiency vs. “X-efficiency”. Am. Econ. Rev. 1966, 56, 392–415. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Nambisan, S.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Wright, M. Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Ren, X. Enterprise Digital Transformation and Capital Market Performance:Empirical Evidence from Stock Liquidity. J. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144+10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, W.; Li, X. How Does Digital Transformation Affect the Total Factor Productivity of Enterprises? Financ. Trade Econ. 2021, 42, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T. Mediating Effects and Moderating Effects in Causal Inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, K.B.; Singhal, V.R. Association between supply chain glitches and operating performance. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B. The network as knowledge: Generative rules and the emergence of structure. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Trajtenberg, M.; Henderson, R. Geographic localization of knowledge spillovers as evidenced by patent citations. Q. J. Econ. 1993, 108, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kallal, H.D.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Shleifer, A. Growth in cities. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 1126–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Wang, K. A Study on the Foreign Investment Promotion Effect of Overseas Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone Construction under the Belt and Road Initiative. Forum World Econ. Politics 2023, 4, 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Feldman, M.P. R&D spillovers and the geography of innovation and production. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 630–640. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Type | Variable | Obs | Mean | Std | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| variable explained | MER | 11,043 | 0.100 | 0.096 | 0.506 | 1.383 |

| core explanatory variable | NBDPZ | 11,043 | 0.158 | 0.365 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| control variable of | size of the board | 11,043 | 2.172 | 0.189 | 0.693 | 2.890 |

| total cash flow | 11,043 | 0.052 | 0.073 | −0.658 | 0.484 | |

| asset-liability ratio | 11,043 | 0.475 | 0.191 | 0.008 | 1.165 | |

| age | 11,043 | 2.705 | 0.538 | 0.000 | 3.555 | |

| nature of equity | 11,043 | 0.552 | 0.497 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| size | 11,043 | 22.427 | 1.325 | 17.641 | 27.638 | |

| return on equity | 11,043 | 0.050 | 0.347 | −16.851 | 2.379 |

| Var | MER (1) | MER (2) | MER (3) | MER (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| did | 0.029 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.007 | 0.023 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.002) | |

| control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| urban fixed effect | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| industry fixed effect | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | No | No | No | Yes |

| N | 11,043 | 11,043 | 11,043 | 11,043 |

| R2 | 0.458 | 0.562 | 0.635 | 0.652 |

| Var | PSM-DID (1) | Exclude the Influence of Similar Policies (2) | Exclude the Impact of External Event Shocks (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| did | 0.023 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.026 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Urban Brain Policy | −0.003 | ||

| (0.002) | |||

| control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| city/industry/year fix effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 11,028 | 11,043 | 7948 |

| R2 | 0.655 | 0.652 | 0.631 |

| Var | Phase 1 | Phase 2 |

|---|---|---|

| did | 0.077 ** | |

| (2.55) | ||

| IV | 0.000007 *** | |

| (9.21) | ||

| control variable | Yes | Yes |

| city/industry/year fix effect | Yes | Yes |

| F-statistics | 84.76 | |

| Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic | 115.083 (p = 0.0000) | |

| Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic | 84.758 | |

| Stock-Yogo weak ID test critical values | 16.38 | |

| N | 10903 | |

| Var | City Region | City Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | North | Central Prefecture-Level Cities | Non-Central Prefecture-Level Cities | |

| did | 0.023 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.028 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| city/industry/year fix effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 7050 | 3967 | 4420 | 6372 |

| R2 | 0.651 | 0.707 | 0.665 | 0.691 |

| Var | Industry Factor Characteristics | Industry Monopoly Degree | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Intensive | Capital Intensive | Labor Intensive | High Degree of Monopoly | Low Degree of Monopoly | |

| did | 0.017 *** | 0.028 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.025 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | |

| control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| city/industry/year fix effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 5757 | 2645 | 2629 | 4529 | 6514 |

| R2 | 0.699 | 0.713 | 0.762 | 0.732 | 0.641 |

| Var | Business Life Cycle | Nature of Enterprise Ownership | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Stage | Growth Stage | Maturity Stage | State-Owned Holding | Non-State-Owned Holding | |

| did | 0.023 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.012 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| city/industry/year fix effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4109 | 3582 | 3352 | 6094 | 4949 |

| R2 | 0.674 | 0.700 | 0.726 | 0.717 | 0.694 |

| Var | (1) Digital Transformation | (2) Innovation and Entrepreneurship Activity Index | (3) Attracting Venture Capital | (4) Number of New Enterprises | (5) Number of Registered Trademarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| did | 0.0216 *** | 0.0172 *** | 0.0174 *** | 0.0216 *** | 0.0118 ** |

| (0.0021) | (0.0029) | (0.0022) | (0.0025) | (0.0043) | |

| did × sz | 0.0005 *** | ||||

| (0.0002) | |||||

| sz | 0.0003 *** | ||||

| (0.0001) | |||||

| did × cx | 0.0011 *** | ||||

| (0.0004) | |||||

| cx | 0.0005 *** | ||||

| (0.0001) | |||||

| did × fxcx | 0.0012 *** | ||||

| (0.0003) | |||||

| fxcx | 0.0002 ** | ||||

| (0.0001) | |||||

| did × xjcx | 0.0008 ** | ||||

| (0.0003) | |||||

| xjcx | 0.0005 *** | ||||

| (0.0001) | |||||

| did × sbcx | 0.0018 *** | ||||

| (0.0043) | |||||

| sbcx | 0.0005 *** | ||||

| (0.0001) | |||||

| control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| city/industry/year fix effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 11,043 | 8405 | 8405 | 8405 | 8405 |

| R2 | 0.654 | 0.634 | 0.634 | 0.634 | 0.635 |

| Var | Supply and Demand Coordination Costs in the Supply Chain | Stability of Supply and Demand in the Supply Chain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Relationship Stability | Supplier Relationship Stability | ||

| did | −0.016 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.012 |

| (0.005) | (0.014) | (0.017) | |

| control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| city/industry/year fix effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 11,043 | 11,043 | 11,043 |

| R2 | 0.198 | 0.252 | 0.319 |

| Var | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fdid | 0.012 *** | 0.025 ** | 0.025 ** | 0.032 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.008) | |

| control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| urban fixed effect | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| industry fixed effect | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | No | No | No | Yes |

| N | 11,043 | 11,043 | 11,043 | 11,043 |

| R2 | 0.448 | 0.563 | 0.636 | 0.651 |

| Hypothesis | Content | Empirical Result | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | The manufacturing enterprises’ resilience in the region is bolstered by NBDPZ. | Significant positive coefficient (Table 2) | Supported |

| H2 | NBDPZ can interact with enterprises’ digital transformation to improve resilience. | Significant positive interaction (Table 8) | Supported |

| H3 | NBDPZ can interact with urban innovation and entrepreneurship activity to improve resilience. | Significant positive interaction (Table 8) | Supported |

| H4 | The NBDPZ can improve resilience through supply chain optimization (cost reduction and stability). | Significant mediating effect (Table 9) | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. The Impact Mechanism and Effect Evaluation of the National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone on the Resilience of Manufacturing Enterprises. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031505

Wang Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Liu J. The Impact Mechanism and Effect Evaluation of the National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone on the Resilience of Manufacturing Enterprises. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031505

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ye, Junnan Liu, Yafei Wang, and Jing Liu. 2026. "The Impact Mechanism and Effect Evaluation of the National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone on the Resilience of Manufacturing Enterprises" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031505

APA StyleWang, Y., Liu, J., Wang, Y., & Liu, J. (2026). The Impact Mechanism and Effect Evaluation of the National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone on the Resilience of Manufacturing Enterprises. Sustainability, 18(3), 1505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031505