Research on Variable Universe Fuzzy Adaptive PID Control System for Solar Panel Sun-Tracking

Abstract

1. Introduction

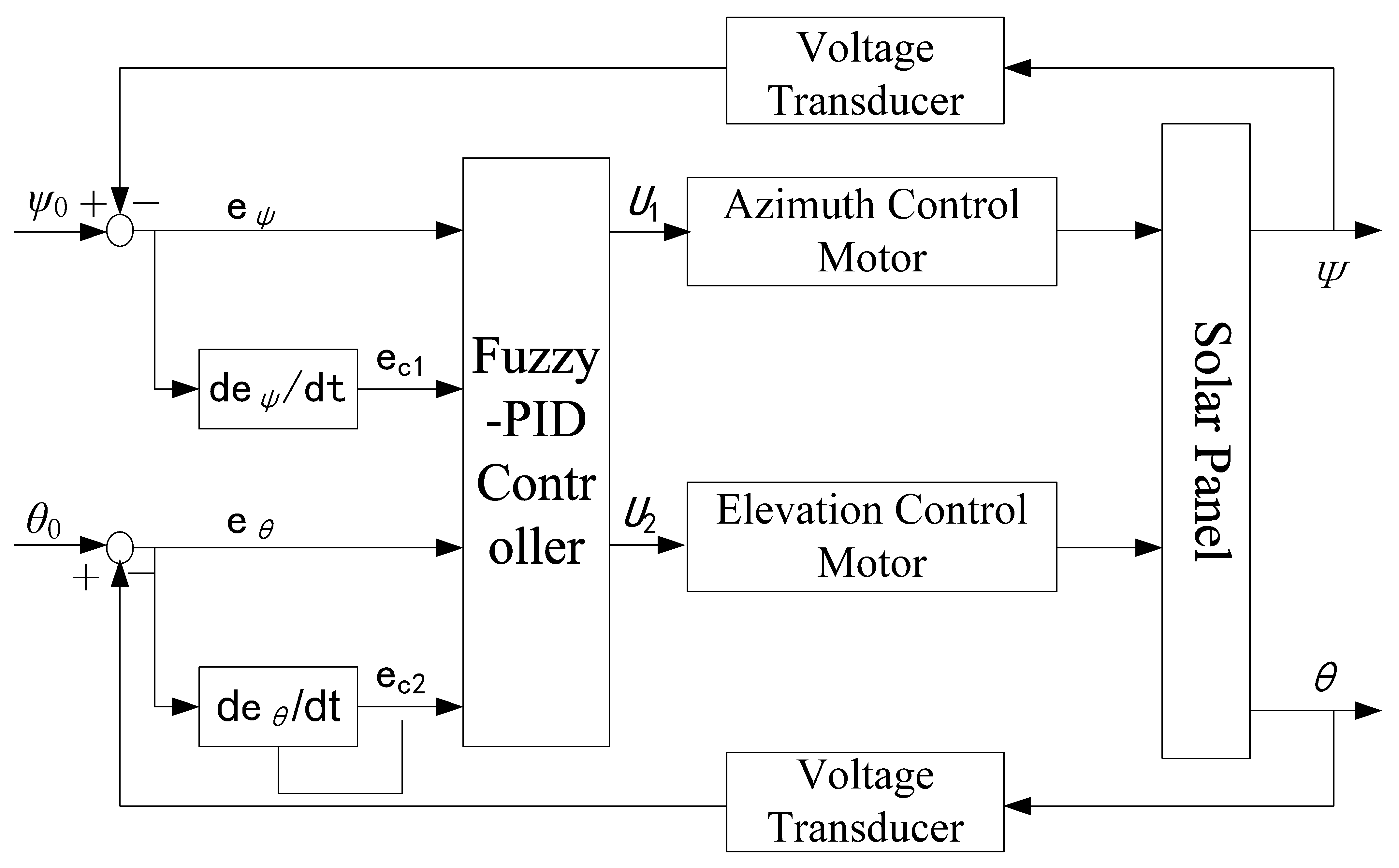

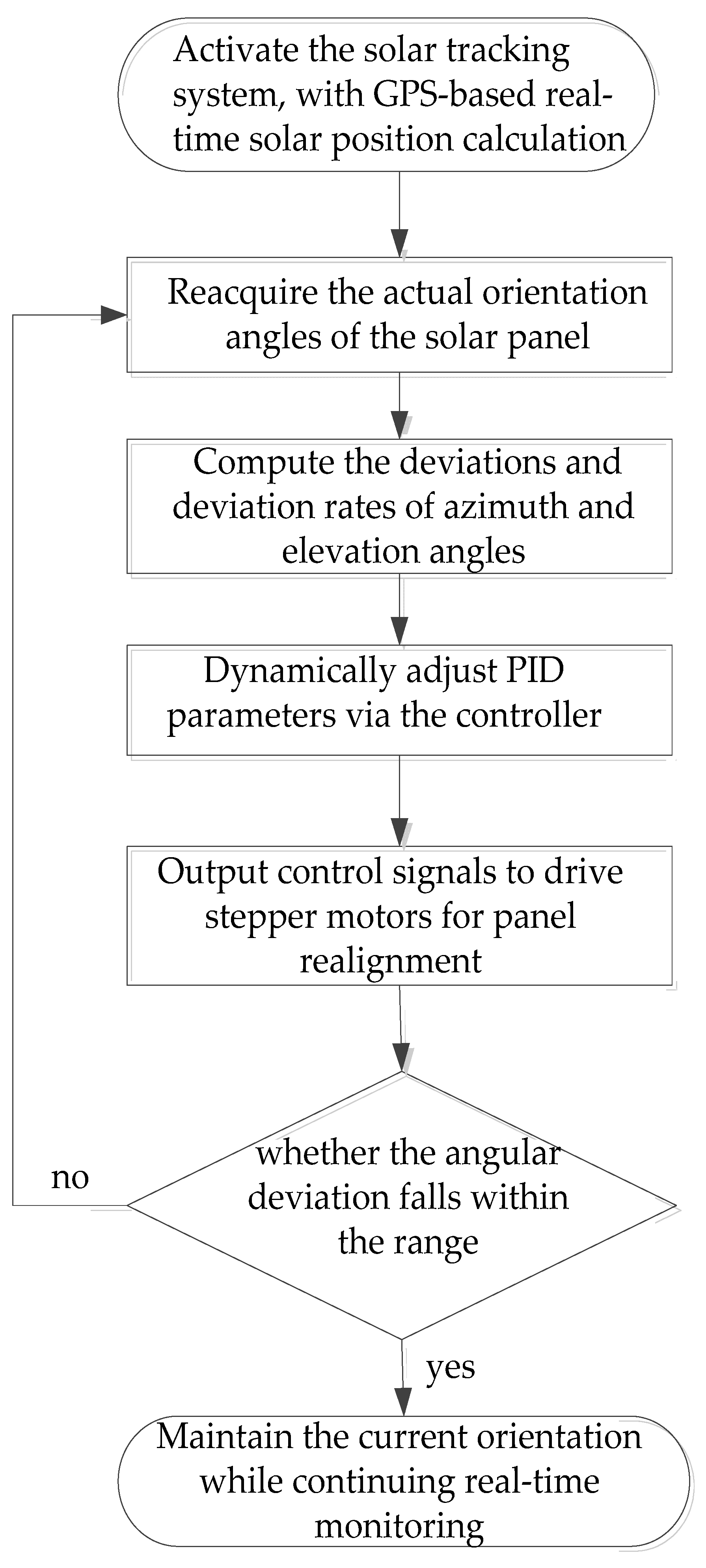

2. Solar Panel Tracking System

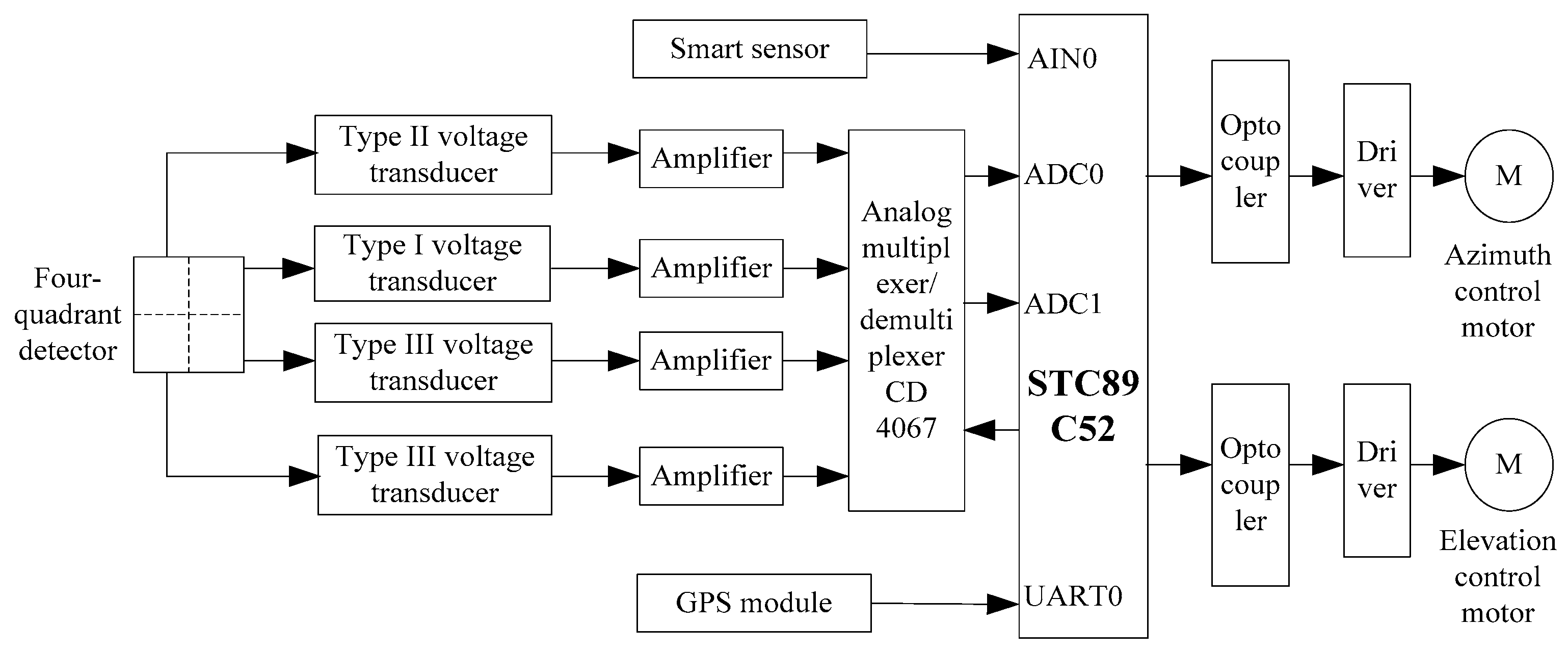

2.1. System Architecture Design

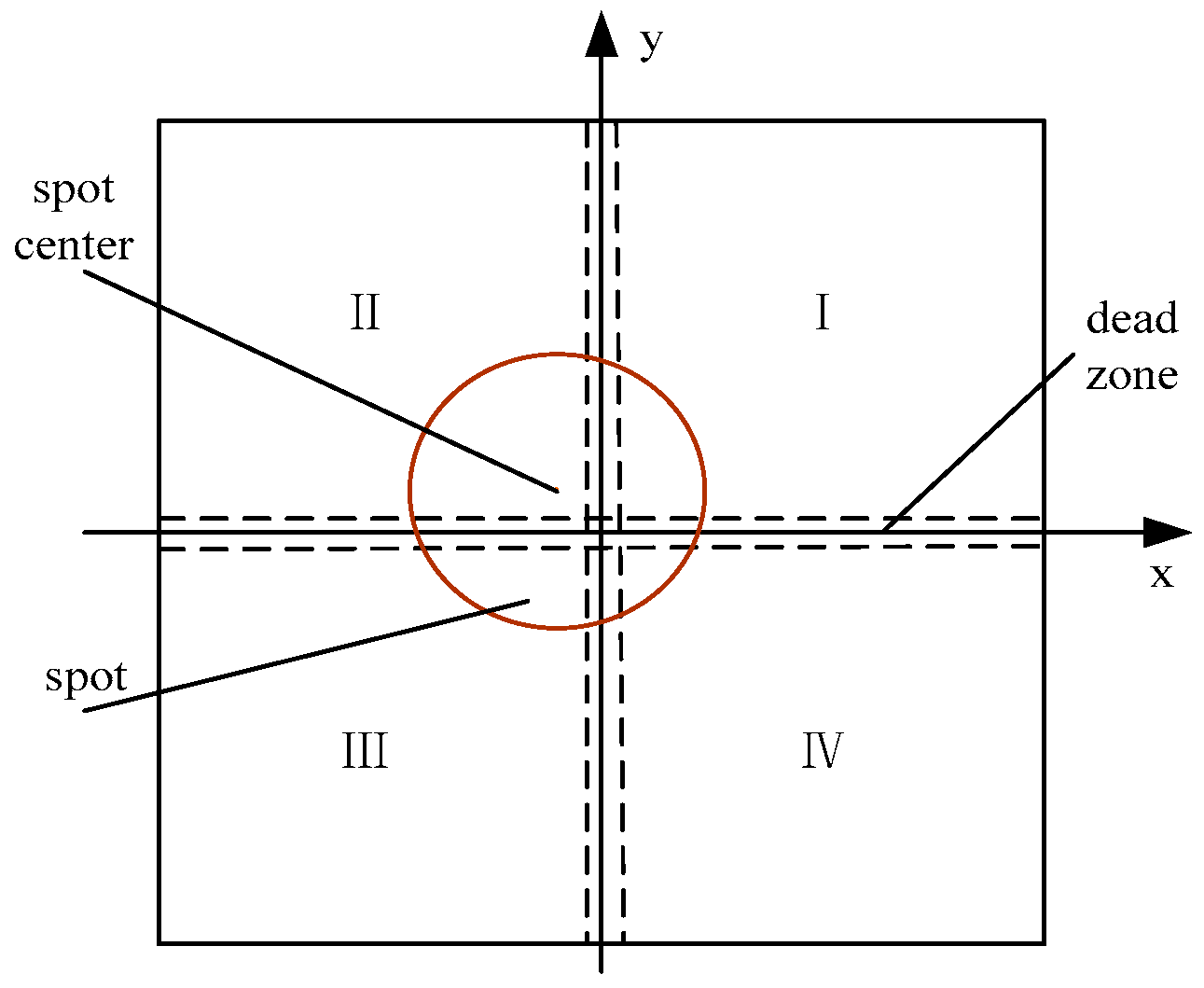

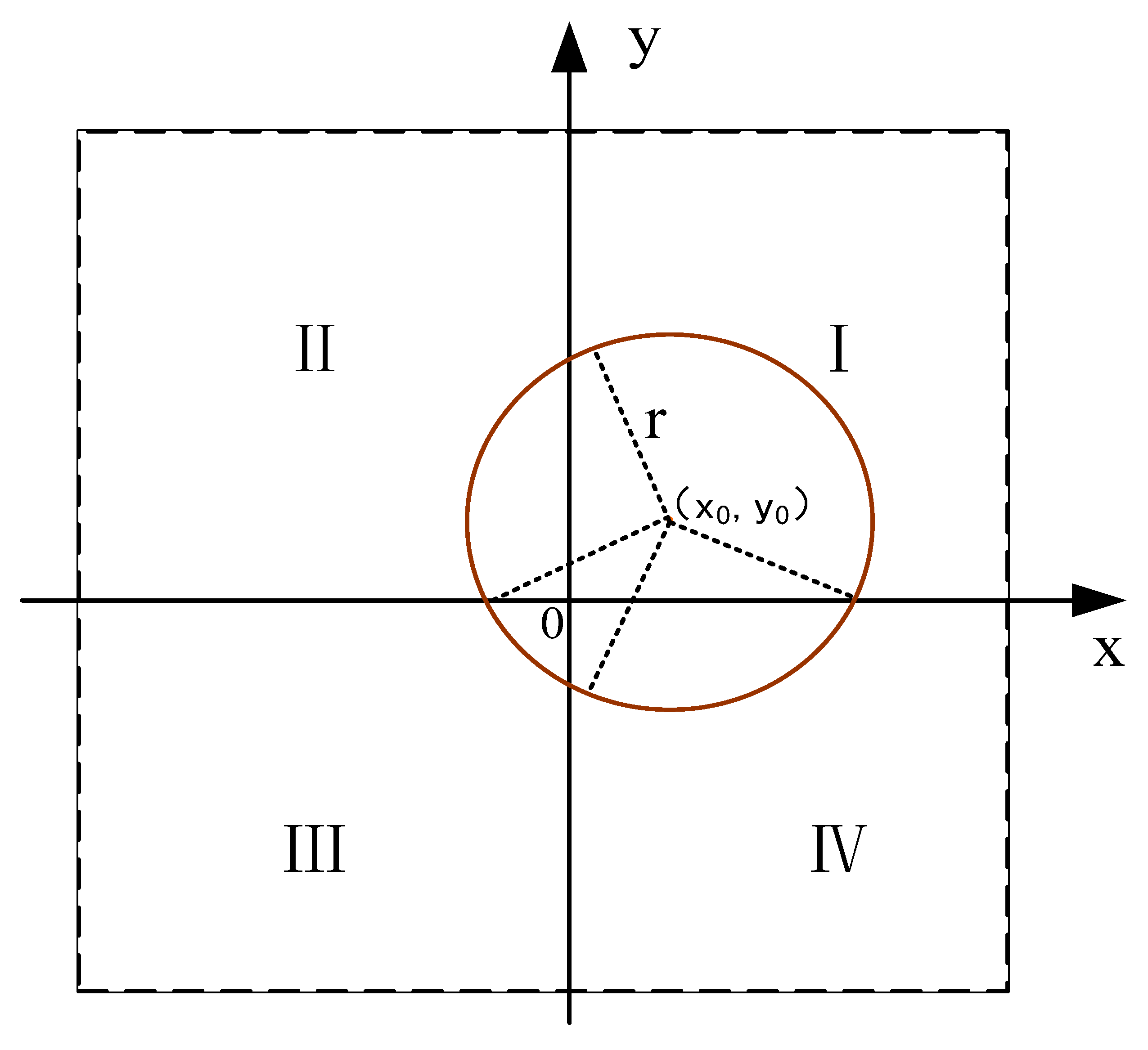

2.2. Light-Tracking Localization Algorithm

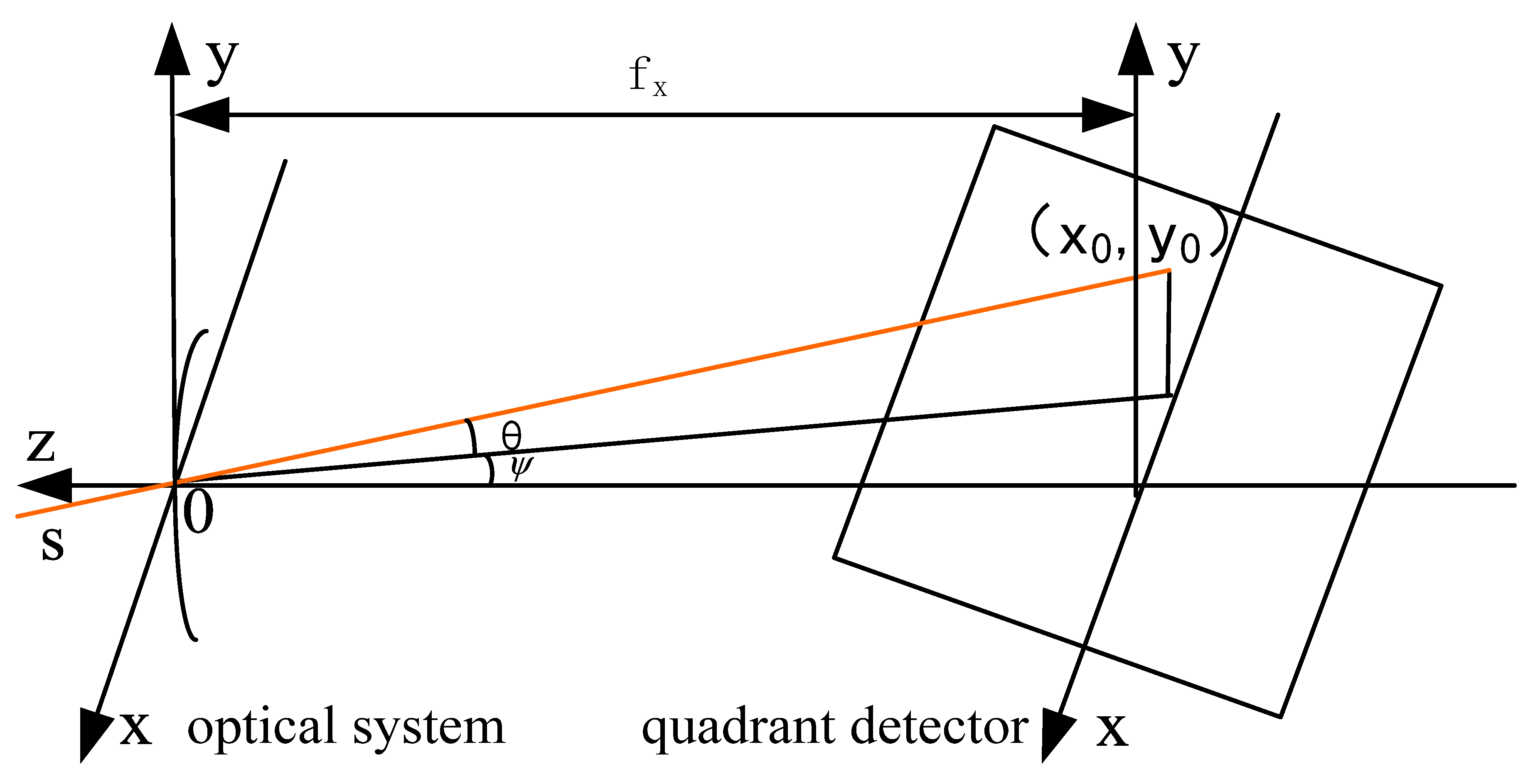

2.3. Calculation of Solar Ray Deflection Angle

3. Design of Solar Tracking Control System

3.1. Conventional PID Controller Design

3.2. Fuzzy PID Controller Design

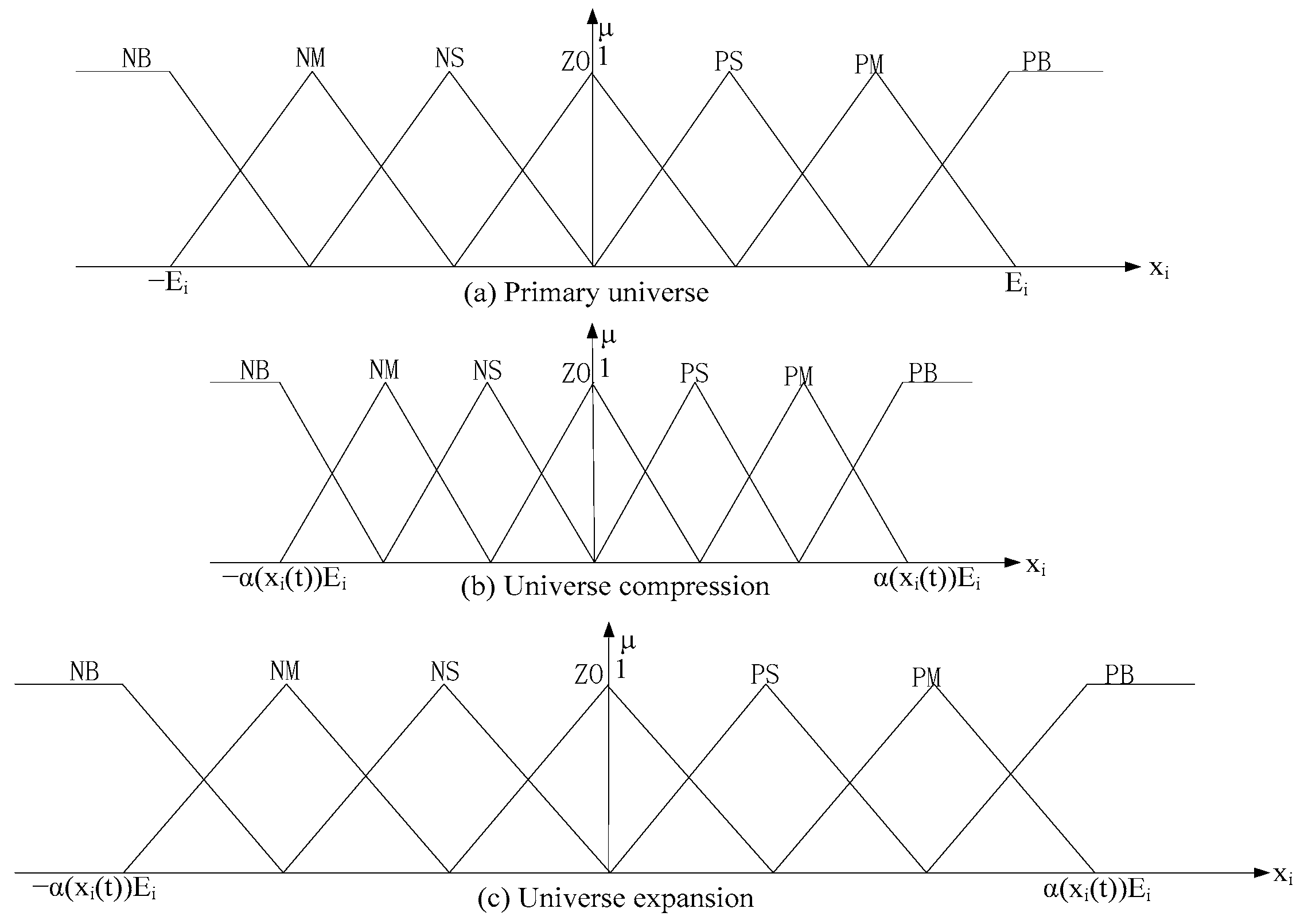

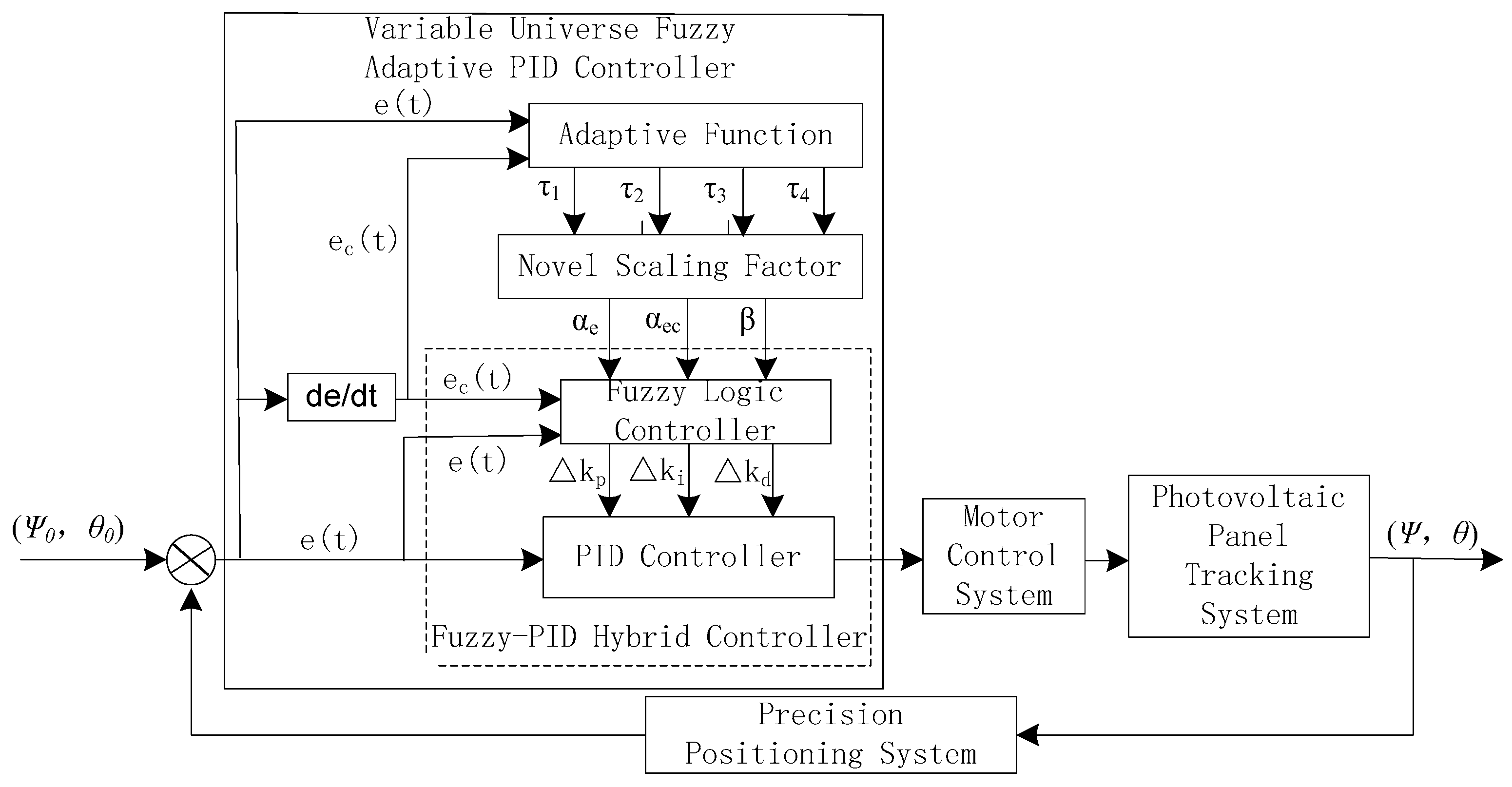

3.3. Design of Variable Universe Fuzzy Adaptive PID Controller

3.3.1. Variable Universe Fuzzy PID Control System

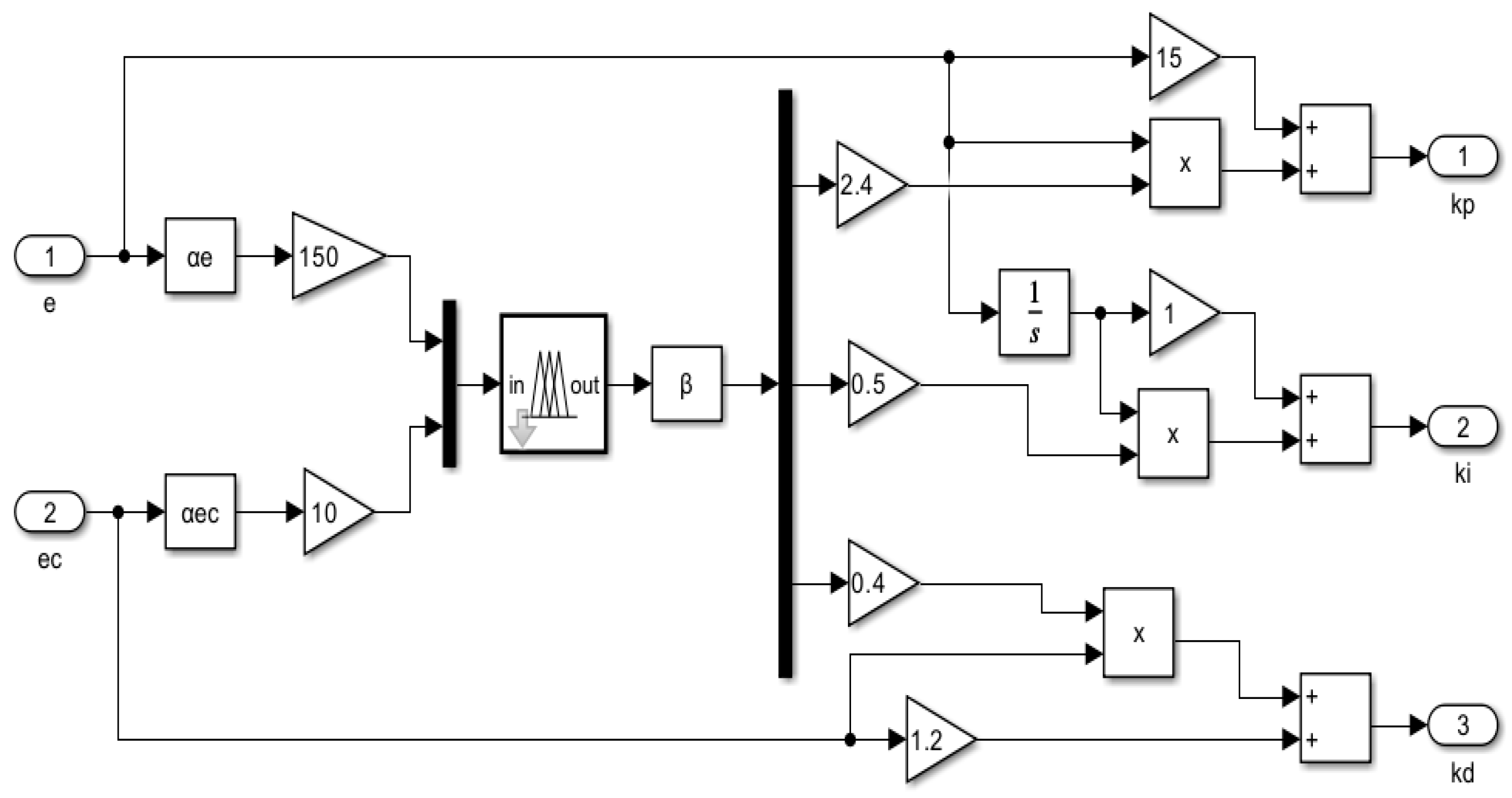

3.3.2. Variable Universe Fuzzy PID Control System with Self-Adaptive Scaling Factor Parameters

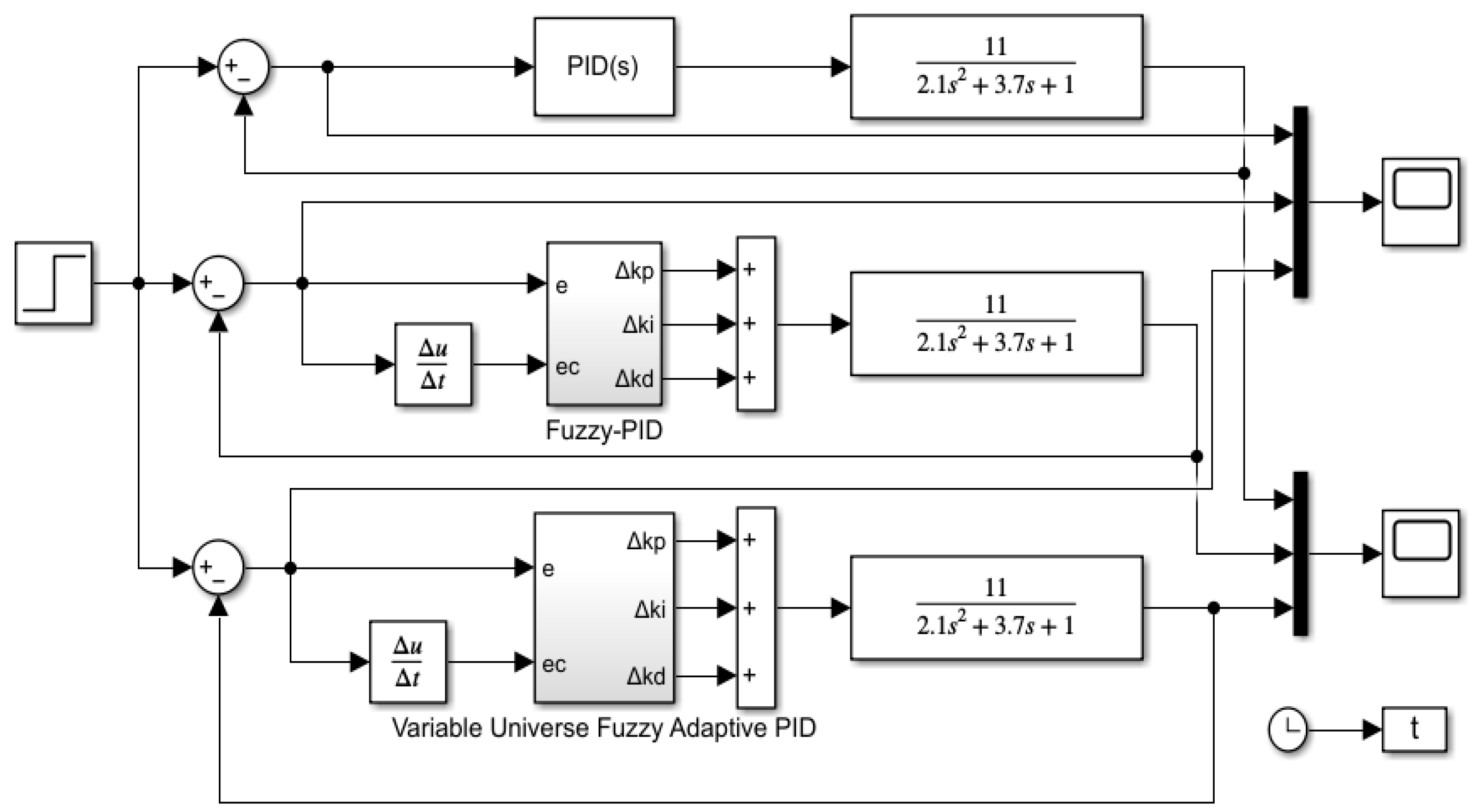

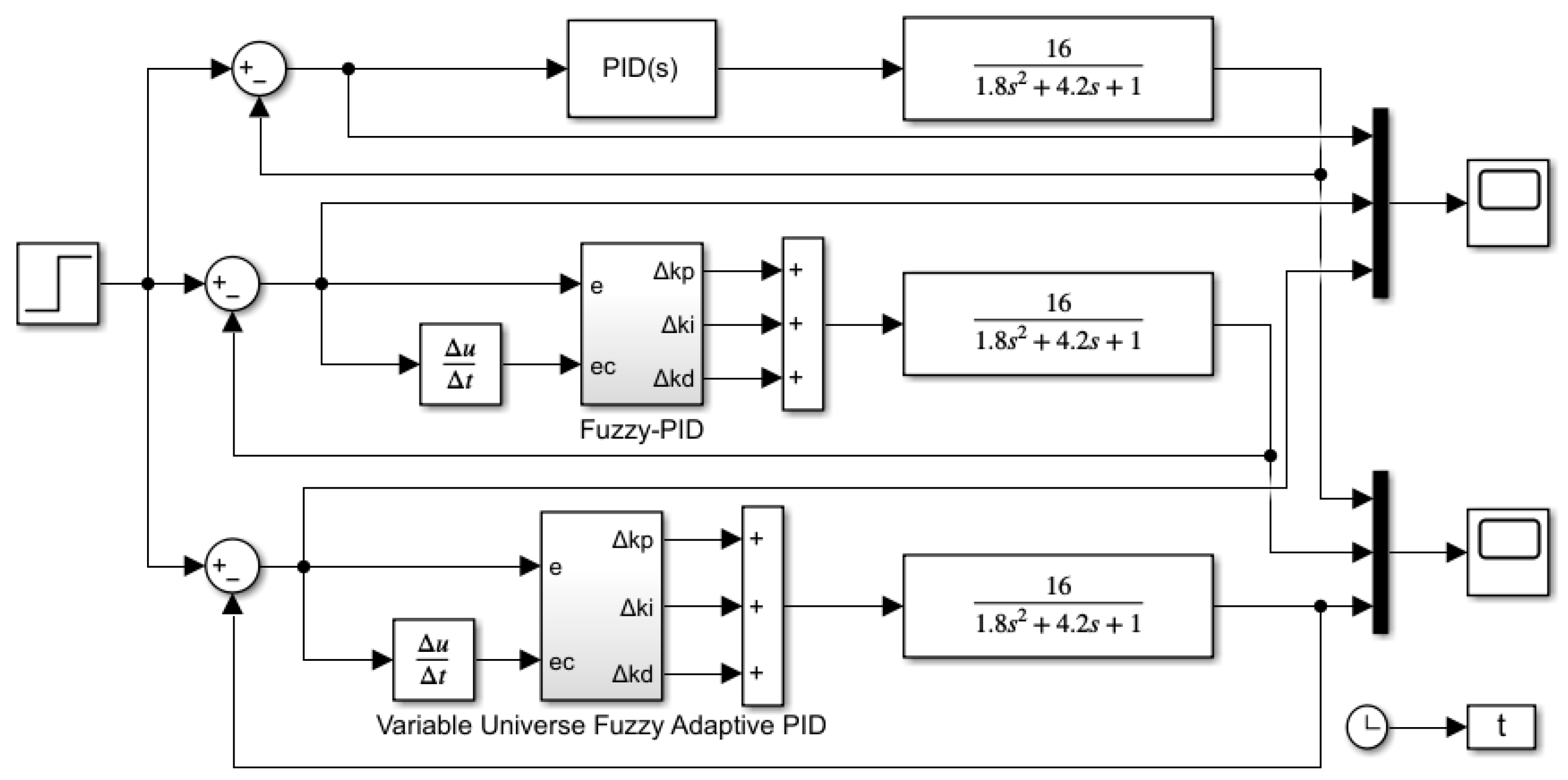

4. Performance Evaluation of Solar Tracking System

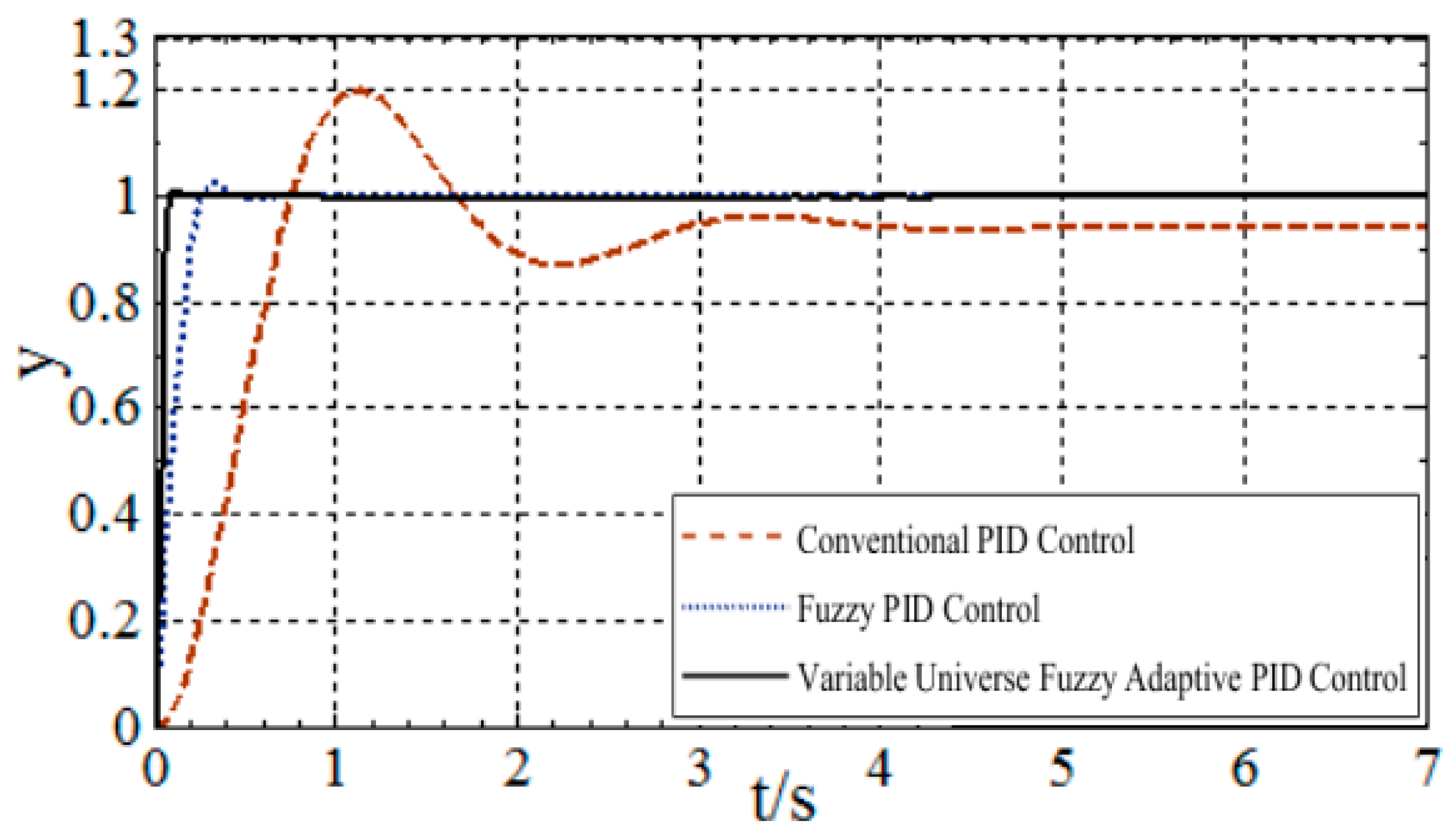

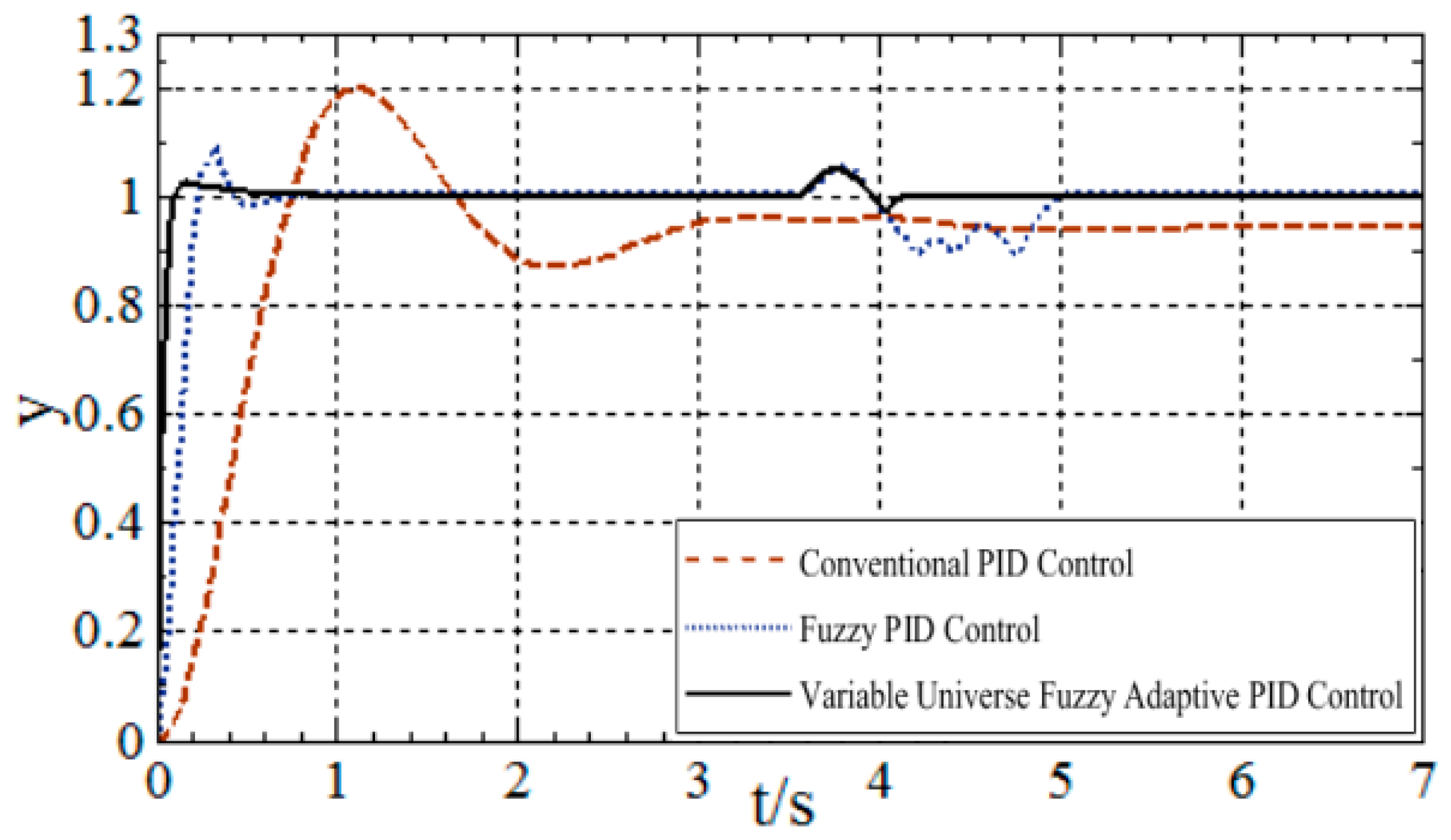

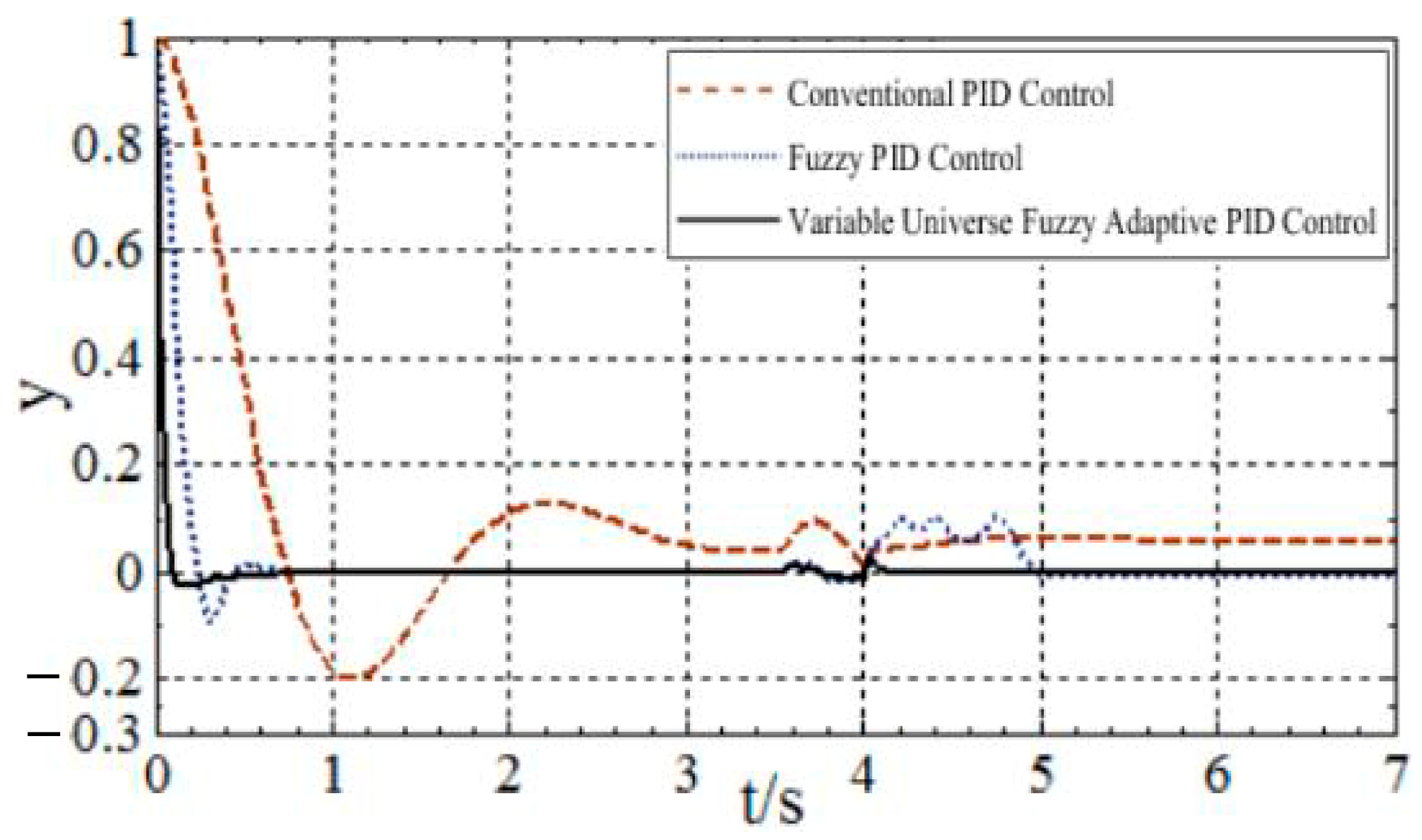

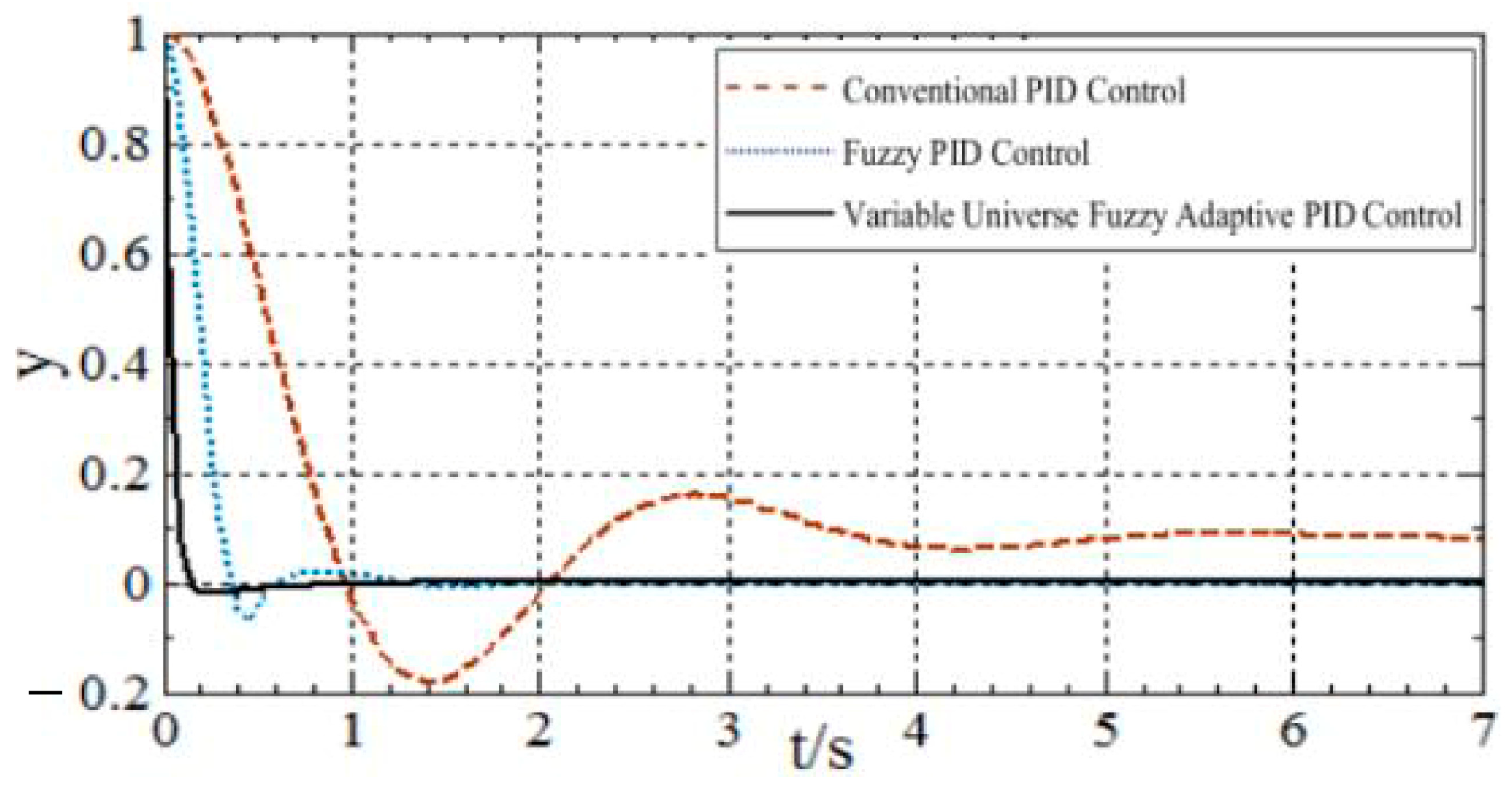

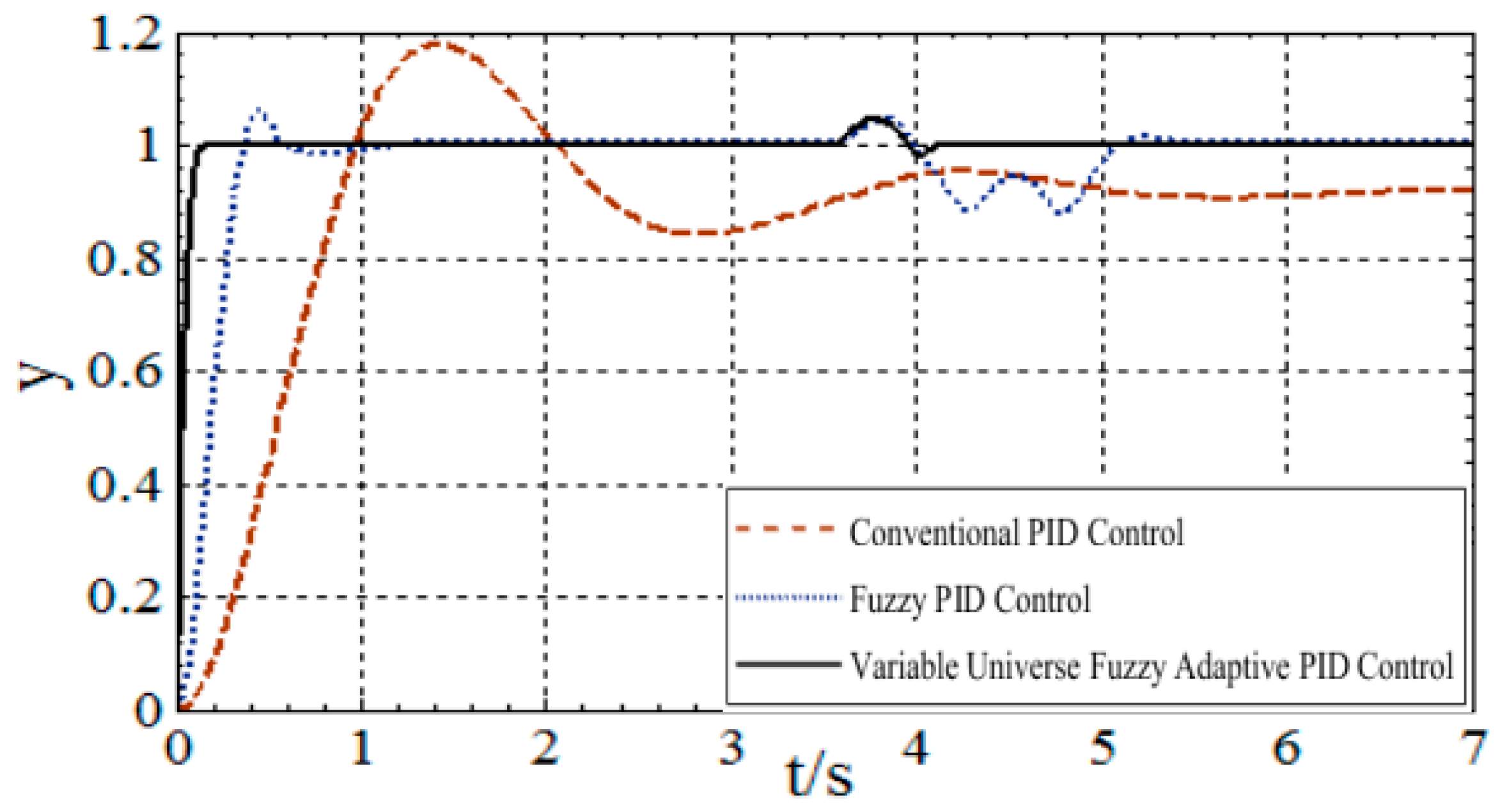

4.1. System Operation Under Ideal Conditions

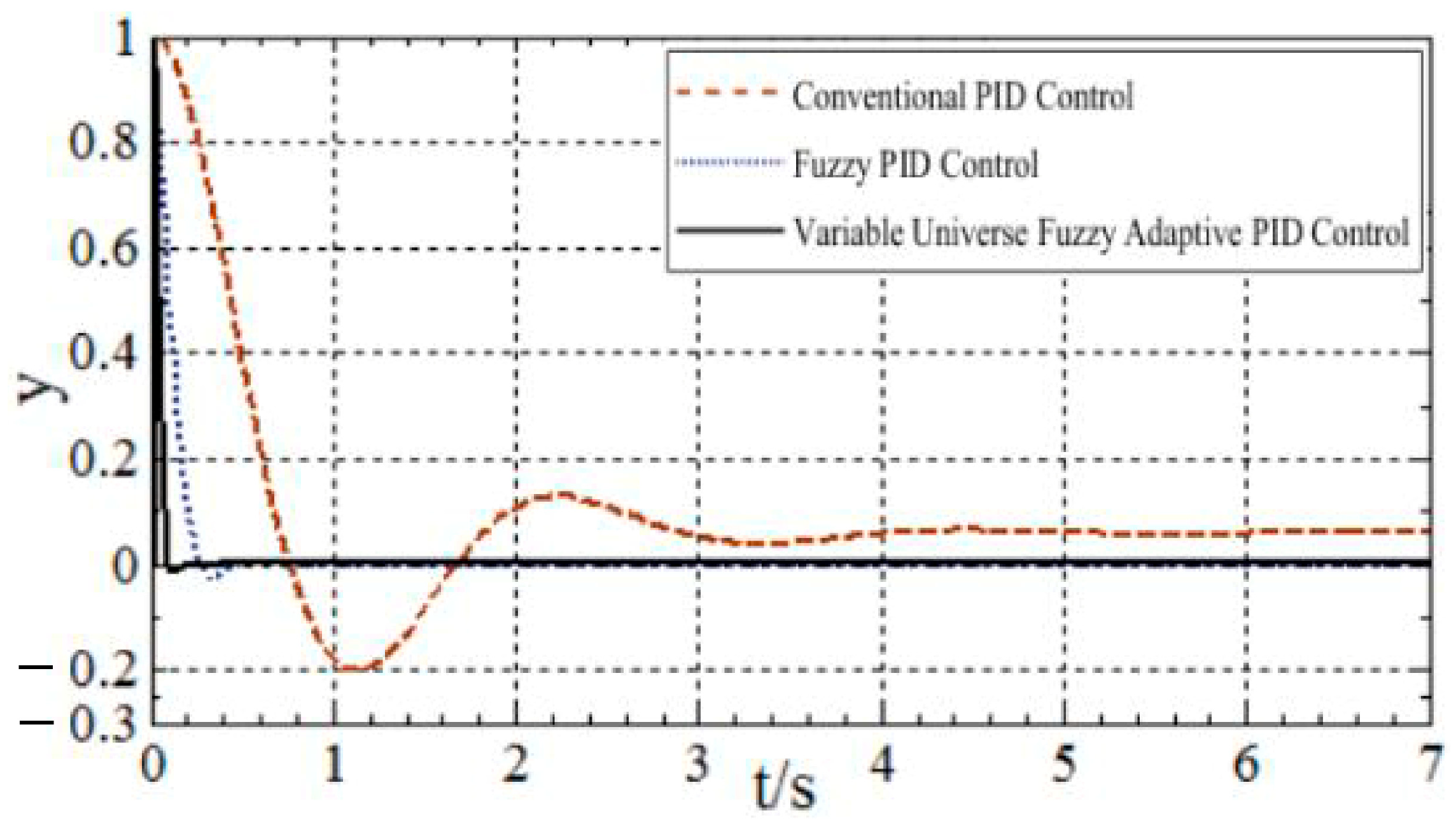

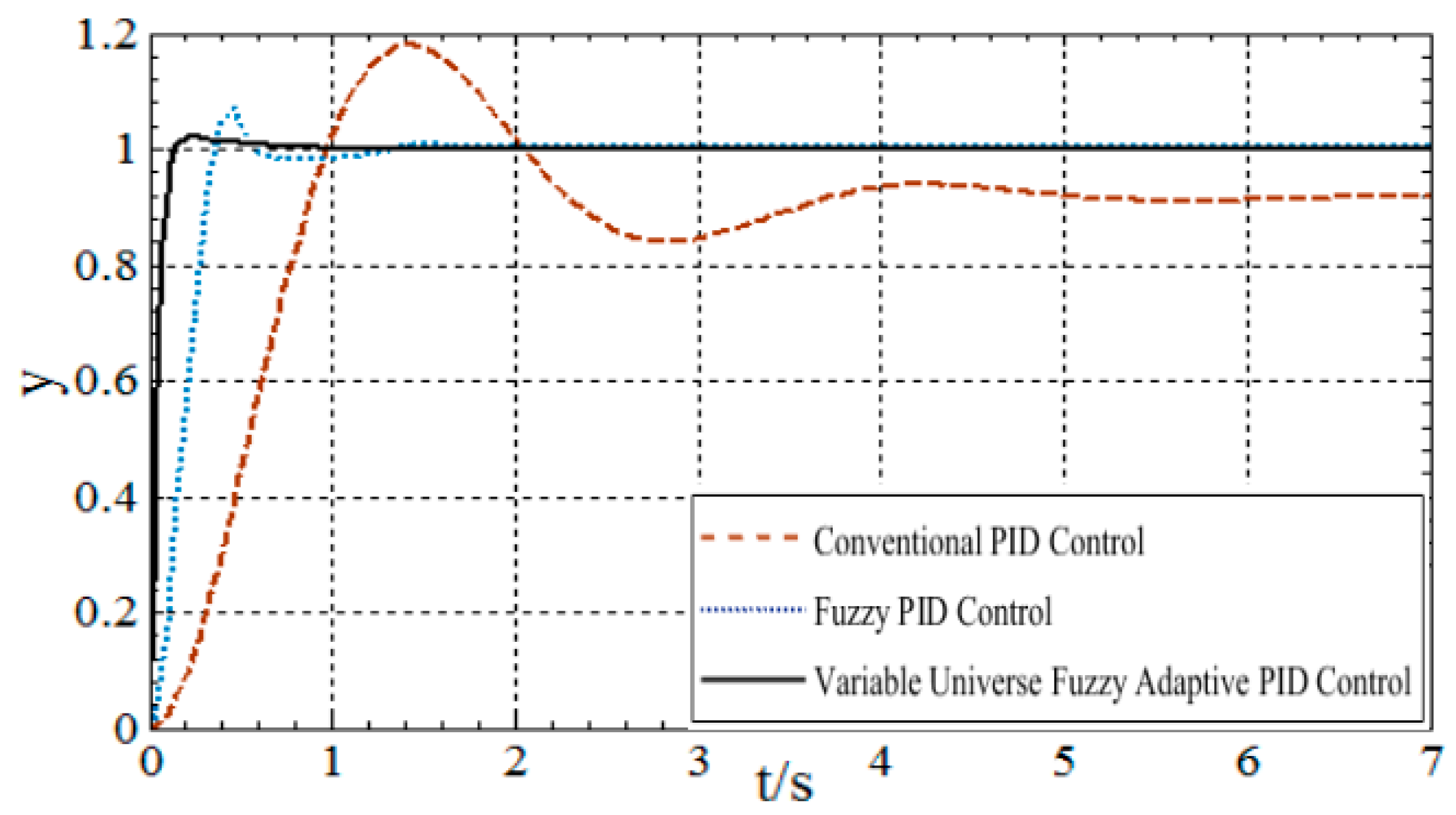

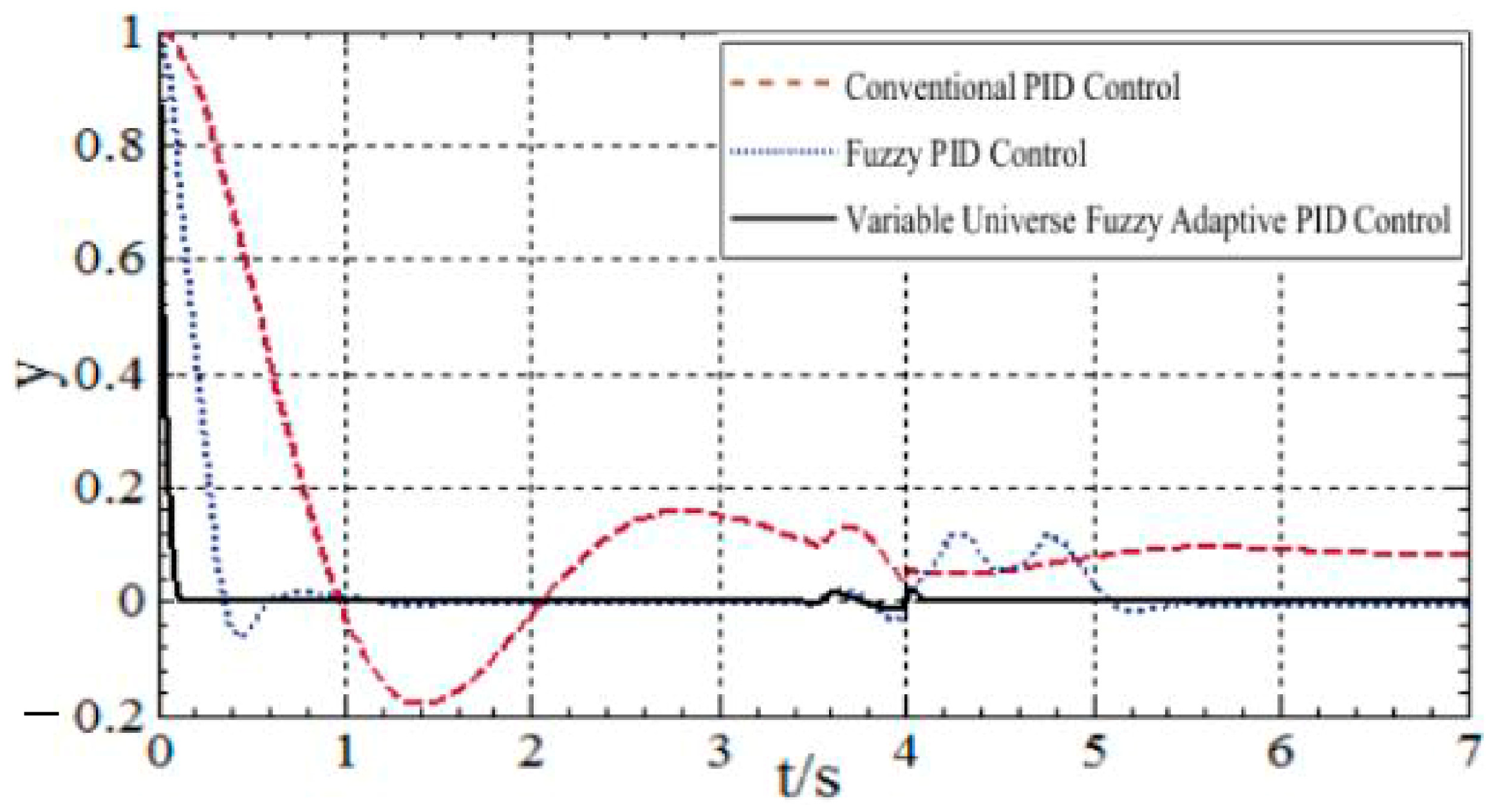

4.2. Complex Operating Environment of Solar Tracking Systems

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaouali, I.; Jebli, M.B.; Gam, I. An assessment of the influence of clean energy and service development on environmental degradation: Evidence for a non-linear ARDL approach for Tunisia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 80364–80377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, R.; Lin, Y. Dynamic role of clean energy and sustainable economic growth in coastal region: Novel observations from China. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukoba, K.; Yoro, K.O.; Eterigho-Ikelegbe, O.; Ibegbulam, C.; Jen, T.C. Adaptation of solar energy in the Global South: Prospects, challenges and opportunities. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wang, W. Potential of China’s national policies on reducing carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants in the period of the 14th Five-Year Plan. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamodiya, U.; Kishor, I.; Garine, R.; Ganguly, P.; Naik, N. Artificial intelligence based hybrid solar energy systems with smart materials and adaptive photovoltaics for sustainable power generation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsiborács, H.; Pintér, G.; Vincze, A.; Hegedűsné Baranyai, N. A Control Process for Active Solar-Tracking Systems for Photovoltaic Technology and the Circuit Layout Necessary for the Implementation of the Method. Sensors 2022, 22, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harazin, J.; Wróbel, A. Analysis and study of the potential increase in energy output generated by prototype solar tracking, roof mounted solar panels. F1000Research 2020, 9, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Ji, H.; Luo, R.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, T. All-Day Freshwater Harvesting Using Solar Auto-Tracking Assisted Selective Solar Absorption and Radiative Cooling. Materials 2025, 18, 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelas, A.; Velázquez, N.; Villa-Angulo, C.; Acuña, A.; Rosales, P.; Suastegui, J. A Solar Position Sensor Based on Image Vision. Sensors 2017, 17, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Uceda, F.J.; Ramirez-Faz, J.; Varo-Martinez, M.; Fernández-Ahumada, L.M. New Omnidirectional Sensor Based on Open-Source Software and Hardware for Tracking and Backtracking of Dual-Axis Solar Trackers in Photovoltaic Plants. Sensors 2021, 21, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayanan, R.; Chitraselvi, S.; Ramanujam, N. A novel development of hybrid maximum power point tracking controller for solar pv systems with wide voltage gain DC-DC converter. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gora, O.; Akkan, T. Development of a Novel Spherical Light-Based Positioning Sensor in Solar Tracking. Sensors 2023, 23, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y. Solar-Blind Ultraviolet Four-Quadrant Detector and Spot Positioning System Based on AlGaN Diodes. Sensors 2025, 25, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, K.; Liu, X.; Yao, Z.; Lu, W.; Yang, W. Improved calibration method of a four-quadrant detector based on Bayesian theory in a laser auto-collimation measurement system. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 5545–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ren, T.; Zhao, B.; Xu, D.; Yang, S.; Ren, D.; Yang, J.; Mo, X.; et al. Research on the simulation method of a BP neural network PID control for stellar spectrum. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 38879–38895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madebo, N.W. Hybrid adaptive PID control strategy for UAVs using combined neural networks and fuzzy logic. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0331036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, H.; Trent, M. Management of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Clinical Practice. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuscheva, A.; Becker, D.; Thompson-Fawcett, M. A 41-Year-Old Patient with a Rare Cause of Severe Abdominal Sepsis Misdiagnosed as PID. Case Rep. Surg. 2018, 2018, 9561798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkarim, N.; Mohamed, A.E.; El-Garhy, A.M.; Dorrah, H.T. A New Hybrid BFOA-PSO Optimization Technique for Decoupling and Robust Control of Two-Coupled Distillation Column Process. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2016, 2016, 8985425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; An, Y.; Xie, P.; Cui, D. Research on Trajectory-Tracking Control System of Tracked Wall-Climbing Robots. Sensors 2023, 24, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zargari, S.; Jarrah, A.; Baghbani, F. Fuzzy-based driver monitoring system to assess dangerous driving on roads. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2025, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Z.; Jia, W.; Ma, X.; Zou, B.; Lin, L. Neural-network-based method for improving measurement accuracy of four-quadrant detectors. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, F9–F14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, H.; Wu, H.; Luo, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, H.; Cui, Z.; Tang, J.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Rotary Wind-driven Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Self-Powered Airflow Temperature Monitoring of Industrial Equipment. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2307382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telle, J.-S.; Upadhaya, A.; Schönfeldt, P.; Steens, T.; Hanke, B.; von Maydell, K. Probabilistic net load forecasting framework for application in distributed integrated renewable energy systems. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 2535–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, L.; Wu, Z.; Wu, J.; Gao, S.; Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, S. High-Precision Log-Ratio Spot Position Detection Algorithm with a Quadrant Detector under Different SNR Environments. Sensors 2022, 22, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Sun, Q.; Xia, C.; Chen, Y.H. Improved Manta Ray Foraging Optimization for PID Control Parameter Tuning in Artillery Stabilization Systems. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euzébio, T.A.M.; Ramirez, M.A.P.; Reinecke, S.F.; Hampel, U. Energy price as an input to fuzzy wastewater level control in pump storage operation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 93701–93712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Das, D.K. A novel PID controller for pressure control of artificial ventilator using optimal rule based fuzzy inference system with RCTO algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, Y. Variable Universe Fuzzy-Proportional-Integral-Differential-Based Braking Force Control of Electro-Mechanical Brakes for Mine Underground Electric Trackless Rubber-Tired Vehicles. Sensors 2024, 24, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, M.; Yu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Qian, Z.; Xie, Z. Modeling and Regulation of Dynamic Temperature for Layer Houses Under Combined Positive- and Negative-Pressure Ventilation. Animals 2024, 14, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| e/ec | ΔKp/ΔKi/ΔKd | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | NM | NS | ZO | PS | PM | PB | |

| NB | PB/NB/PS | PB/NB/PS | PM/NM/NB | PM/NM/NB | PS/NS/NB | ZO/ZO/NM | ZO/ZO/PS |

| PM/PM/PB | |||||||

| NM | PB/NB/PS | PM/NM/PS | PM/NM/NB | PS/NS/NM | PS/NS/NM | ZO/ZO/NS | NS/ZO/ZO |

| ZO/PM/PM | |||||||

| NS | PM/NB/NS | PM/NM/NM | PS/NS/NM | PS/NS/NM | ZO/ZO/NS | NS/PS/NS | NS/PS/ZO |

| ZO/PB/PM | |||||||

| ZO | PM/NM/ZO | PS/NS/NS | PS/NS/NS | ZO/ZO/NM | NS/PS/NS | NM/PM/NS | NM/PM/ZO |

| NM/NB/PB | |||||||

| PS | PS/PS/ZO | PS/PS/ZO | ZO/ZO/ZO | NS/NS/ZO | NS/NS/ZO | NM/PM/ZO | NM/NM/NS |

| PS/NS/NS | |||||||

| PM | PS/NS/PB | ZO/ZO/NS | NS/PS/PS | NM/PM/PS | NM/PM/PS | NB/PB/PS | NB/PB/NM |

| NM/NS/PM | |||||||

| PB | Z0/ZO/PB | ZO/ZO/PM | NM/PS/PM | NM/PM/PM | NM/PM/PS | NB/PB/PM | NB/PB/PB |

| PS/NS/NS | |||||||

| e/ec | α(e(t))/α(ec(t))/β | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB | CM | CS | ZO | ES | EM | EB | |

| CB | EB/CB/ES | EB/CB/ES | EM/CM/CB | EM/CM/CB | ES/CS/CB | ZO/ZO/CM | ZO/ZO/ES |

| EM/EM/EB | |||||||

| CM | EB/CB/ES | EM/CM/ES | EM/CM/CB | ES/CS/CM | ES/CS/CM | ZO/ZO/CS | CS/ZO/ZO |

| ZO/EM/EM | |||||||

| CS | EM/CB/CS | EM/CM/CM | ES/CS/CM | ES/CS/CM | ZO/ZO/CS | CS/ES/CS | CS/ES/ZO |

| ZO/EB/EM | |||||||

| ZO | EM/CM/ZO | ES/CS/CS | ES/CS/CS | ZO/ZO/CM | CS/ES/CS | CM/EM/CS | CM/EM/ZO |

| CM/CB/EB | |||||||

| ES | ES/ES/ZO | ES/ES/ZO | ZO/ZO/ZO | CS/CS/ZO | CS/CS/ZO | CM/EM/ZO | CM/CM/CS |

| ES/CS/CS | |||||||

| EM | ES/CS/EB | ZO/ZO/CS | CS/ES/ES | CM/EM/ES | CM/EM/ES | CB/EB/ES | CB/EB/CM |

| CM/CS/EM | |||||||

| EB | Z0/ZO/EB | ZO/ZO/EM | CM/ES/EM | CM/EM/EM | CM/EM/ES | CB/EB/EM | CB/EB/EB |

| ES/CS/CS | |||||||

| Parameter Category | Symbol | Value/Setting | Basis/Derivation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Controller Values | Initial PID parameters Kp0, Ki0, Kd0 | 8.0, 0.5, 0.1 | Determined based on standard tuning criteria. |

| Initial Universe of Discourse Boundaries | Error (e) initial universe | [−15°, 15°] | Determined based on standard tuning criteria. |

| Error change rate (ec) initial universe | [−10°/s, 10°/s] | Determined based on standard tuning criteria. | |

| Output ΔKp, ΔKi, ΔKd initial universe | [−2, 2], [−0.5, 0.5], [−0.1, 0.1] | Calculated from the basic universe of discourse and scaling factors. | |

| Scaling Factor Parameters | Constant ε | 0.0001 | Refer to Equation (19). |

| Constant δ | 0.01 | Refer to Equation (18). |

| Control Algorithm | Steady-State Error (±°) | Settling Time (s) | Rise Time (s) | Overshoot (%) | Disturbance Recovery Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional PID | 4~5 | 5–6 | 0.7 | 20 | 2 |

| Fuzzy PID | 1~2 | 0.6–1 | 0.18 | 2–10 | 1.5 |

| Variable Universe Fuzzy Adaptive PID | 0.1~0.5 | 0.2–0.6 | 0.1 | 1–2 | 0.7 |

| Interference Combination | Validation Set RMSE (RLS) | Conventional Least Squares (LS) RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| Cloud Cover + Wind Disturbance | 7.2% | 14.8% |

| Temperature Drift + Panel Dust Accumulation | 6.5% | 13.3% |

| Multi-Interference Overlap (Cover + Wind + Temperature) | 8.1% | 16.2% |

| Control Algorithm | Steady-State Error (±°) | Settling Time (s) | Rise Time (s) | Overshoot (%) | Disturbance Recovery Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional PID | 4~6 | 6–6.6 | 0.85 | 19 | 2.2 |

| Fuzzy PID | 1~3 | 1.6–2.4 | 0.28 | 8–10 | 2 |

| Variable Universe Fuzzy Adaptive PID | 0.1~0.8 | 0.4–0.6 | 0.15 | 0–1.5 | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ding, Z.; Yao, Y.; Gao, S.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Ren, J.; Dong, J.; Wu, J.; Ma, F.; Liu, X. Research on Variable Universe Fuzzy Adaptive PID Control System for Solar Panel Sun-Tracking. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031503

Ding Z, Yao Y, Gao S, Yang X, Li C, Ren J, Dong J, Wu J, Ma F, Liu X. Research on Variable Universe Fuzzy Adaptive PID Control System for Solar Panel Sun-Tracking. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031503

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Zhiqiang, Yanlin Yao, Shiyan Gao, Xiyuan Yang, Caixiong Li, Jifeng Ren, Jing Dong, Junhui Wu, Fuliang Ma, and Xiaoming Liu. 2026. "Research on Variable Universe Fuzzy Adaptive PID Control System for Solar Panel Sun-Tracking" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031503

APA StyleDing, Z., Yao, Y., Gao, S., Yang, X., Li, C., Ren, J., Dong, J., Wu, J., Ma, F., & Liu, X. (2026). Research on Variable Universe Fuzzy Adaptive PID Control System for Solar Panel Sun-Tracking. Sustainability, 18(3), 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031503