1. Introduction: Establishing the Modeling Paradox

Urban sustainability is increasingly defined not only by resource efficiency but also by the resilience of the built environment against anthropogenic and natural hazards. In this context, the integration of Human-Centric Digital Twins offers a novel paradigm for quantifying ‘spatial sustainability’. While Hillier has established spatial configuration as a fundamental driver of urban sustainability [

1] and Marcus and Colding have linked spatial morphology directly to the resilience of urban systems [

2], the operational limits of these forms under acute stress remain underexplored. Building on Dempsey et al.’s definition of the social dimension of sustainability, which emphasizes the role of urban form in community identity [

3], we define spatial sustainability in this study as the capacity of an urban form to support life safety without compromising its morphological identity. By utilizing procedural Virtual Reality (VR) as a calibration tool for evacuation modeling, this study addresses this socio-technical gap. It provides a methodological framework to measure how specific spatial configurations perform under stress, ensuring that the preservation of urban identity in complex settlements can coexist with rigorous safety standards. Consequently, this approach supports the development of evidence-based policies for resilient urban management, aligning with the broader goals of measuring and monitoring sustainable urban systems.

1.1. The Problem: A Paradox in Urban Disaster Modeling

Contemporary urban resilience studies increasingly use agent-based modeling (ABM) to simulate evacuations, mainly because of its ability to handle the spatial and systemic complexities of urban settings [

4]. ABM’s key benefit is its bottom-up approach, where large-scale patterns like congestion and bottlenecks arise from the interactions of individual agents. This enables precise representation of various urban forms and infrastructure networks [

5]. Nevertheless, this methodological strength reveals a significant epistemic limitation rooted in the behavioral core of most implementations. Although spatial modeling has become more advanced, behavioral modeling remains limited due to an ongoing “data scarcity crisis” [

6]. Without detailed empirical data on human choices in extreme situations, modelers often make simplified assumptions, viewing agents as rational entities with almost complete knowledge of their environment [

4]. However, empirical research consistently shows a gap between these rational assumptions and actual evacuation behavior. Real evacuations feature high variability, nonlinear decision-making, and heuristics driven by stress, rather than optimization [

7,

8]. As a result, there is a significant discrepancy between ABM assumptions and human responses, raising concerns about the accuracy of simulations used for policy-making in critical scenarios.

1.2. Related Work: Urban Heterogeneity and the Limits of Generalization

Calibration challenges are amplified by the significant morphological heterogeneity of urban fabrics. Although standardized ABM frameworks perform adequately in orthogonal, grid-based environments where spatial legibility is high, their predictive capacity deteriorates markedly in organic or historic urban tissues [

9]. In such settings, non-hierarchical street networks and fragmented visibility undermine the plausibility of simplified behavioral rules.

Systematic reviews show that most evacuation studies concentrate on well-organized indoor spaces or standardized outdoor areas like campuses, thus systematically underestimating the complexity of diverse urban environments [

4,

10]. This creates a dual problem: current models do not accurately capture the cognitive disorientation experienced in complex settings, and obtaining the empirical data required to improve these models is extremely challenging. This issue is especially prominent in informal settlements and areas with a long history of urban development, where spatial complexity is a key feature [

11,

12].

1.3. The Proposed Solution: A Calibration Framework

The main challenge in resolving this paradox is the lack of detailed behavioral data across different morphological conditions [

4,

13]. Traditional approaches like evacuation drills or retrospective studies are frequently limited by ethical concerns or logistical difficulties when trying to determine the causal impact of urban form [

14,

15].

This study presents a methodological synthesis that combines two technologies: procedural environment generation and immersive VR. Procedural generation allows for the rule-based creation of diverse urban forms without relying on site-specific data. At the same time, VR serves as a “behavioral wind tunnel” [

7], a controlled environment where human performance can be tested under psychologically meaningful stress [

16]. Procedural generation functions as a morphological engine capable of producing an unlimited variety of urban configurations. Together, these methods support a calibration paradigm that moves beyond context-specific assumptions to develop a generalizable and empirically grounded understanding of human behavior.

1.4. Aim and Contribution

The main goal of this research is not to validate a model for a particular site but to develop a generalizable methodological framework for deriving behavioral parameters from procedurally generated environments. Its contribution is explicitly methodological. Rather than creating outputs tied to specific contexts, this work introduces a reproducible protocol for extracting context-sensitive locomotion rules from controlled VR experiments.

To illustrate this framework, we compare two distinct urban archetypes: a standard orthogonal grid (Type B) and an irregular, organic layout (Type A). By experimentally changing visibility conditions within these forms, the study shows that the framework can detect differences in locomotion patterns based on morphology. This confirms that the approach effectively captures behavioral variations influenced by spatial structure, providing a reliable alternative to assumptions that ignore morphology.

To address the behavioral gaps in current evacuation modeling, this study is grounded in the ‘Configurational Primacy’ hypothesis. We posit that while distinct urban morphologies may yield comparable navigation performance under optimal conditions, the underlying spatial configuration becomes the dominant predictor of evacuation efficiency as environmental stress increases and sensory information degrades. Accordingly, this research aims to answer the following question: To what extent does urban morphology dictate wayfinding behavior when agents are subjected to sensory deprivation constraints typical of disaster scenarios?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 outlines the theoretical framework, discussing the limitations of current ABM calibration and the potential of VR as a behavioral measurement tool.

Section 3 details the methodological pipeline, including the procedural generation of urban archetypes and the VR experimental protocol.

Section 4 presents the results, highlighting the behavioral divergence observed between orthogonal and organic morphologies.

Section 5 discusses the implications of ‘structural legibility’ for urban resilience and redefines panic as a spatial variable. Finally,

Section 6 addresses the study’s limitations, and

Section 7 offers concluding remarks on integrating these findings into algorithmic parameterization.

2. Theoretical Framework and Justification

2.1. The Calibration Crisis in Agent-Based Evacuation Modeling

Systematic reviews consistently show that most published ABM studies depend on behavioral parameters based on normative assumptions, generalized findings, or expert judgment rather than direct empirical data [

4,

17]. This dependence is due to structural limitations, as obtaining suitable calibration data through usual methods is often difficult due to ethical or logistical reasons. Conventional approaches face specific limitations. Evacuation drills, though ecologically valid, are restricted by ethical concerns against causing real fear and typically involve small, non-representative groups [

15,

18].

Additionally, they do not allow for systematic changes to environmental factors like visibility or spatial layout. Likewise, analyzing real-world evacuation videos yields genuine behavioral data but is retrospective and opportunistic, influenced by unique contextual conditions that hinder controlled comparisons [

19]. This data scarcity has implications that go beyond mere statistical uncertainty. Without empirically based inputs, modelers often rely on simplified decision rules that presume ideal performance, such as shortest-path routing and perfect situational awareness [

20]. Such assumptions tend to bias simulation results by underestimating evacuation times and hiding hesitation or maladaptive responses typical of human behavior under stress [

4]. As a result, many evacuation models, despite their advanced spatial features, lack realistic behavioral dynamics, undermining their reliability for evidence-based emergency planning.

2.2. Virtual Reality as Behavioral Measurement Infrastructure

The advancement of immersive VR provides a significant solution to this empirical gap. Evidence from systematic reviews shows that well-crafted VR experiments trigger behavioral responses that closely match real-world evacuation actions, especially in exit choice and route selection [

7,

21,

22]. VR is not just a substitute for reality but a practical experimental tool built on three key strengths: ecological validity, experimental control, and ethical acceptability.

Regarding ecological validity, modern VR systems have reached a level of immersive fidelity sufficient to evoke psychologically meaningful stress responses and cognitive load, closely simulating real evacuation scenarios [

8,

23]. Although stress levels induced by VR are still lower than in actual disasters, empirical evidence shows that key behavioral patterns, such as hesitation during decision-making and speed adjustments, show acceptable statistical correlation when proper calibration is used [

7,

21].

Regarding experimental control, VR significantly surpasses real-world methods by enabling systematic manipulation of individual environmental variables while holding others constant [

22,

24]. This advantage overcomes the limitations of observational data, where spatial and situational factors are often intertwined. In contrast, VR allows for factorial designs that explicitly test causal links between environmental structure and behavioral responses.

Finally, VR overcomes the ethical challenges in evacuation research by enabling the simulation of high-stress scenarios, such as darkness and structural ambiguity, that would be unethical to replicate in real life [

8,

23]. This broadens the scope of data collection, allowing researchers to study decision-making in environments of high uncertainty, where traditional ABM assumptions tend to be less reliable.

2.3. Synthesis: The ABM-VR Integration as Methodological Infrastructure

The integration of ABM and VR highlights a key complementarity between two analytical systems functioning at interconnected scales. VR facilitates detailed observation of individual decision-making in controlled settings, providing micro-level evidence that is otherwise difficult to access. Meanwhile, ABM offers a scalable structure to incorporate these individual behaviors into complex spatial environments, enabling the projection of these rules to larger population dynamics [

4]. In this context, the integrated VR-to-ABM framework formalizes the connection: behavioral parameters obtained from VR are directly translated into ABM inputs, replacing assumption-based specifications with evidence-driven calibration.

This synthesis tackles the “generalization problem” in evacuation modeling, where parameters calibrated for one type of morphology do not transfer well to others. Instead of assuming behavior is always the same, the framework considers it as dependent on environmental structure. By integrating procedural generation with VR, we develop conditional behavioral rules, functions that define how locomotion, decision-making speed, and route selection change with spatial arrangements.

The result is not a single, specific model for one site, but a set of parameterized rules that can be applied to a wide range of urban layouts. At the core of this integration is a conceptual shift of VR from merely a training tool to a precise tool for measuring behavior [

25,

26]. It functions as a “behavioral wind tunnel,” providing experimental infrastructure akin to engineering test facilities. In evacuation modeling, this positions VR as the primary empirical basis for calibrating behavior, strengthening the connection between real human performance and computational models.

3. Methodology: The Proposed Framework

This section outlines the methodological architecture developed to address the calibration gap identified in

Section 2. While the construction of this framework constitutes a primary output of this research, it functions here as the operational protocol for the experimental validation detailed in the subsequent subsections. Specifically, this section bridges the theoretical requirements established in

Section 2 with the empirical application analyzed in

Section 4, detailing how procedural generation and VR are synthesized to create a controlled testing environment.

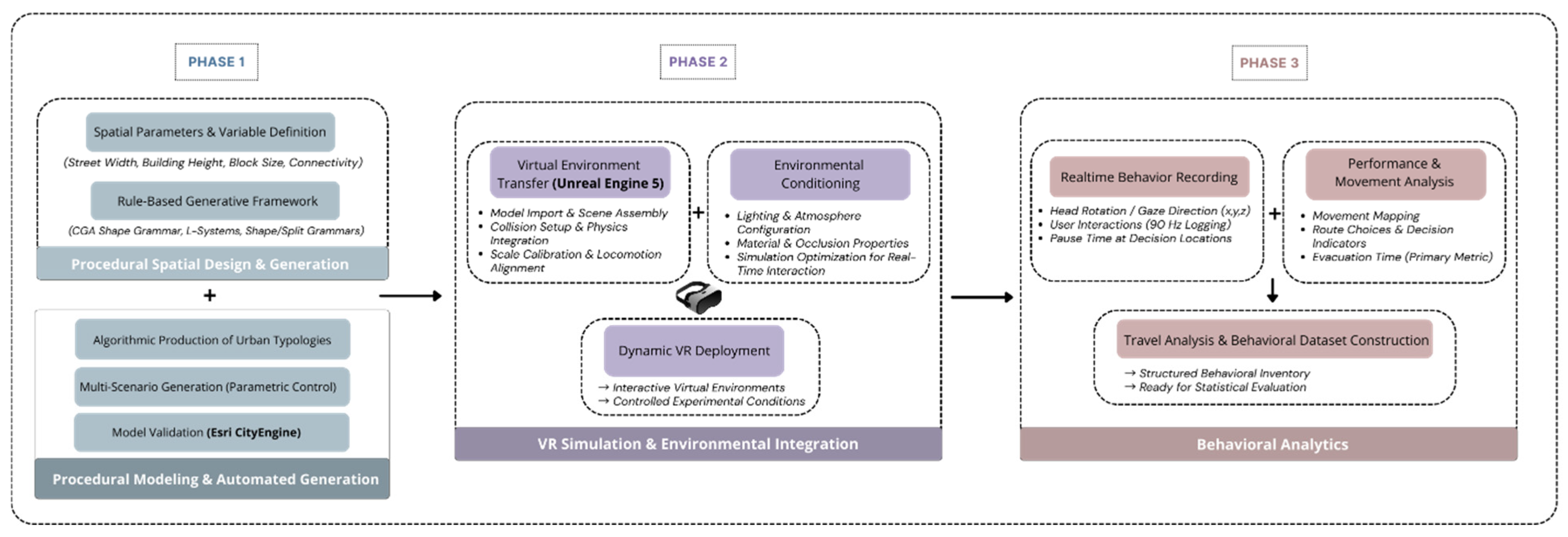

3.1. Framework Architecture and Operational Logic

The proposed framework combines procedural generation, VR experiments, and ABM via a structured data transformation pipeline that converts abstract spatial descriptions into empirically based behavioral rules. Its architecture is composed of five consecutive stages:

Parametric Specification: Urban morphological features, such as connectivity, enclosure, and angular variability, are characterized using numerical parameters.

Procedural Instantiation: These parameters are algorithmically converted into three-dimensional virtual environments that reflect specific spatial properties without replicating any real-world location.

Immersive VR Experimentation: The created environments serve as controlled stimuli in experiments where human navigation behaviors are monitored under different stress levels.

Behavioral Data Mining: Trajectory data collected at high frequency are analyzed to uncover consistent movement patterns and decision-making processes.

Rule Translation: Behavioral patterns identified are formalized into agent-level rules suitable for ABM simulation.

The framework is built on two main design principles: context-independence and reproducibility. Context-independence means the methodology works with abstract morphological parameters instead of location-specific data. Using a limited set of geometric descriptors like street-width distributions or intersection variance, the framework can be applied even in data-scarce settings, such as informal settlements, conflict areas, or unbuilt zones.

Reproducibility is ensured by developing the full workflow as an open-source computational pipeline (see

Figure 1). Every transformation phase is controlled by clear, inspectable algorithms, allowing others to verify, replicate, and build upon the work. This transparency directly tackles long-standing issues related to the “black box” nature of ABM implementations, where behavioral rules are frequently unclear or poorly documented [

4,

5].

3.2. Procedural Environment Generation: From Parameters to Instantiation

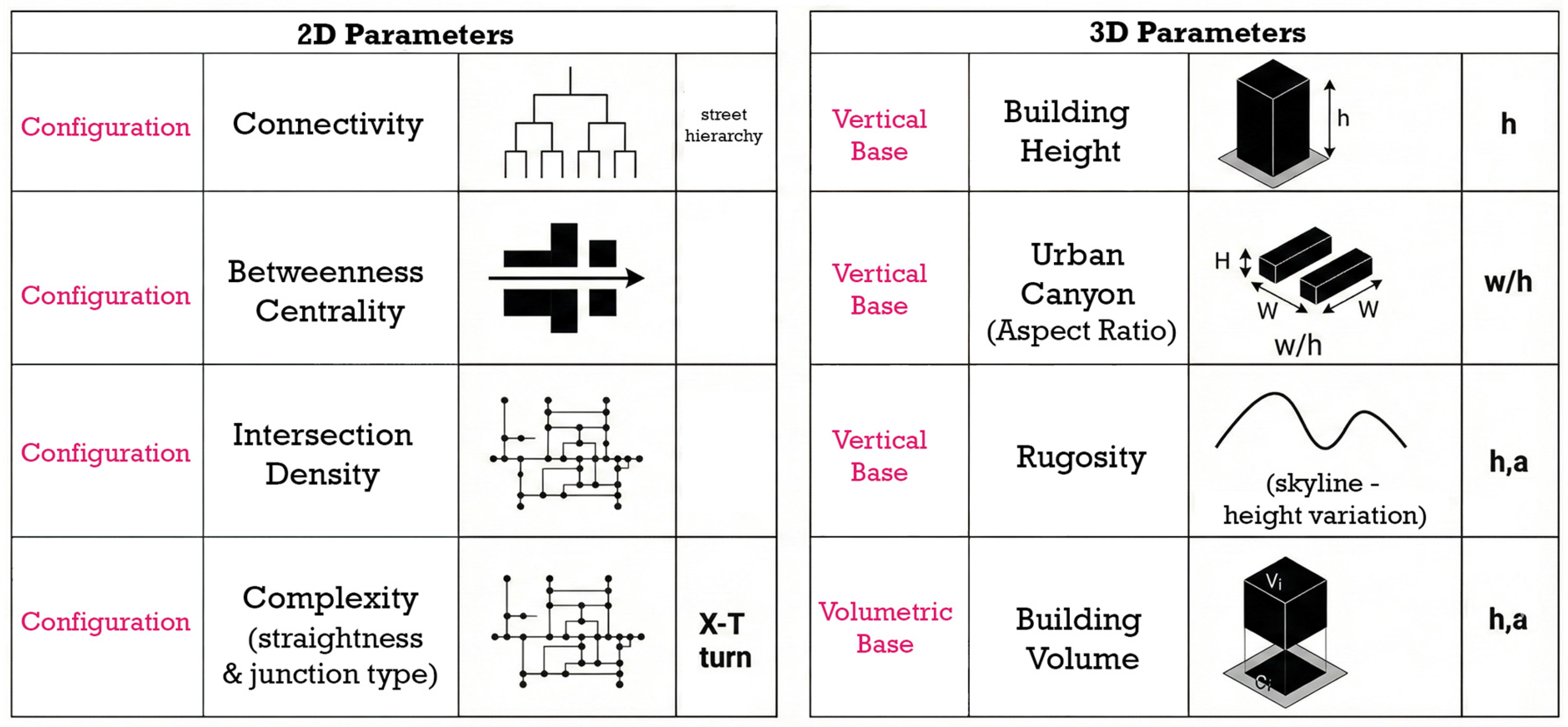

The procedural generation component utilizes constraint-based algorithms to translate abstract morphological parameters into fully navigable, three-dimensional virtual environments. To ensure valid experimental contrasts, the parameter space was rigorously defined through a systematic literature review focusing on disaster resilience and wayfinding, identifying critical morphological determinants. The generation process is driven by two distinct variable sets to measure volumetric impact on decision-making (see

Figure 2):

Two-dimensional Configuration (Planar): Operationalized through Connectivity, Betweenness Centrality, and Intersection Topology. Specifically, the frequency of X-type (crossing) vs. T-type (decision) intersections and the calculation of turn penalties were prioritized as primary variables affecting route complexity.

Three-dimensional Volumetric (Vertical): To measure the impact of the built environment on cognitive load, we introduced Building Height (h), Building Volume, Urban Canyon Ratio (W/H), and Rugosity (R). Rugosity defines the “roughness” or irregularity of the street edge (setbacks and protrusions), which impacts visual scanning and isovist properties.

By isolating these variables, the framework aims to measure how specific 3D attributes (e.g., a towering narrow canyon vs. a low-rise wide street) influence route choice when 2D connectivity remains constant.

Figure 2.

Configurational parameters for urban archetypes. Note. Adopted from the author’s unpublished doctoral dissertation (Author, in preparation).

Figure 2.

Configurational parameters for urban archetypes. Note. Adopted from the author’s unpublished doctoral dissertation (Author, in preparation).

The procedural generation component uses constraint-based algorithms to convert abstract morphological parameters into fully navigable, three-dimensional virtual environments. Building on proven techniques from computer graphics and urban morphology, this method allows the creation of spatial configurations that are structurally unique but still parametrically controlled. The generation process relies on a set of variables that are supported by both empirical data and theoretical understanding, and these variables are directly related to wayfinding performance:

Street Network Connectivity: Measured by intersection density and average node degree, which determine how accessible the network is in terms of topology.

Geometric Regularity: Assessed using angular deviation from orthogonality, which affects how easy the layout is to understand.

Spatial Enclosure: Defined by the ratio of building height to street width, influencing how users perceive density and their visual range.

Visual Complexity: Indicated by the density of façade details and landmark features, which impact cognitive load.

During the sample area generation phase, a stochastic constraint synthesis method was employed. Environments were created as potential layouts that satisfied the defined parameter ranges. Since this process is probabilistic, it enables comparison of multiple spatial configurations that are structurally similar (isomorphic in core directions) but differ in composition. This allows researchers to speculate on the systematic effects of urban morphological parameters on behavior across different urban fabrics that share the same parameters, by examining human behavior in different urban forms with comparable parametric characteristics, rather than analyzing a single settlement plan.

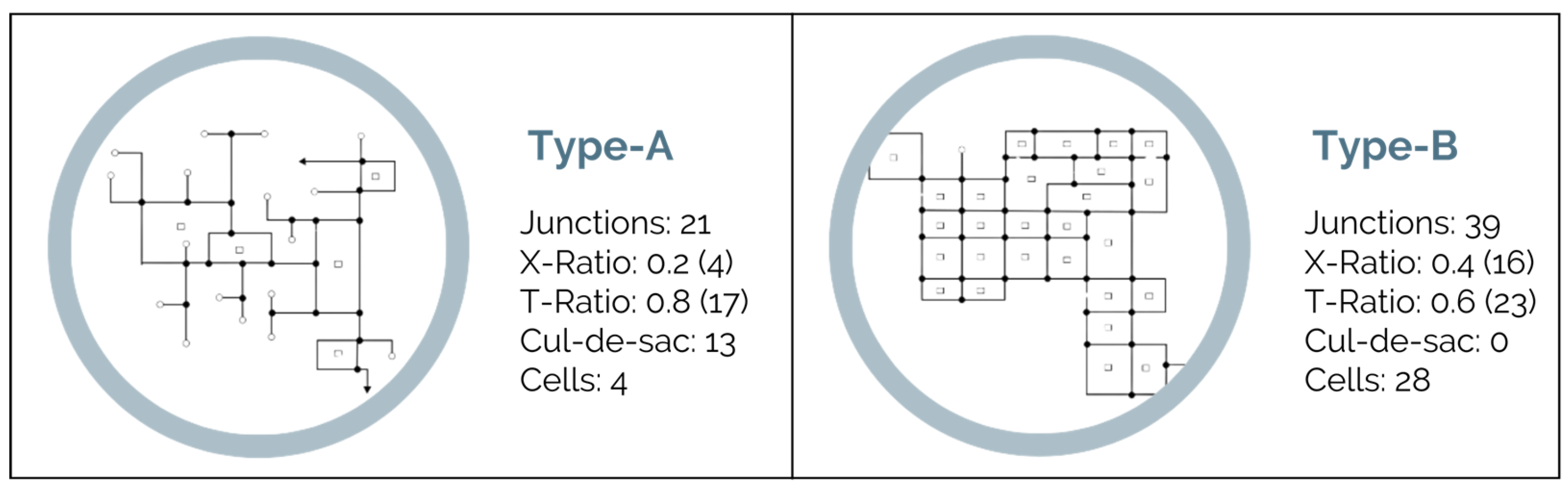

3.3. Methodological Operationalization: The Archetypal Contrast

To empirically validate the framework’s sensitivity, a proof-of-concept study was conducted using two morphologically contrasting urban archetypes derived from Marshall’s [

27] discussion on

Streets and Patterns. These archetypes were generated as typological extremes to test the Configurational Primacy hypothesis.

3.3.1. Exclusion of Confounding Variables

To ensure that observed behavioral divergence originates solely from physical morphology, a strict isolation protocol was applied. The experimental environments were intentionally maintained as static abstractions. We deliberately excluded dynamic elements such as crowd simulation, vehicular traffic, or changing hazards. While real-world evacuations are inherently social, introducing these variables at this stage would introduce confounding factors (e.g., herding behavior or collision avoidance) that obscure the specific impact of spatial configuration. This abstract geometric fidelity approach (see

Figure 3) ensures that navigation relies exclusively on the affordances of the built form (e.g., street width, junction angles, building bulk) rather than on social cues.

3.3.2. Archetype A: The Organic Configuration

Archetype A operationalizes the morphological properties of historic urban cores or organically evolved districts.

Composition: Characterized by high angular variability, irregular street widths (W1/W2), and significant rugosity (R).

Network Statistics: The layout features 21 junctions with a dominant T-ratio of 0.8 (17 T-junctions vs. 4 X-junctions) and 13 cul-de-sacs.

Syntactic Properties: In Space Syntax terms, this layout exhibits high topological depth and low global integration. The scarcity of long axial lines (L1) and fragmented sightlines restricts anticipatory perception, intentionally elevating cognitive load to simulate the disorientation found in complex informal settlements.

3.3.3. Archetype B: The Orthogonal Configuration

Archetype B represents the rational, planned urban grid.

Composition: Characterized by consistent street widths, orthogonal intersections (90°), and low rugosity.

Network Statistics: The layout features 39 junctions with a significantly higher X-ratio of 0.4 (16 X-junctions vs. 23 T-junctions) and zero cul-de-sacs, maximizing permeability.

Syntactic Properties: This configuration exhibits high connectivity and intelligibility. The prevalence of X-junctions and long linear corridors (L2) creates “visual tunnels” that serve as cognitive anchors, allowing participants to infer global structure from local cues.

3.3.4. Scenario Distribution

To prevent learning effects and ensure statistical robustness, morphological parameters (e.g., High/Low Building Height, Wide/Narrow Street) were distributed stochastically across the intersection points. The experimental design ensured that each participant encountered a balanced distribution of these parameter combinations (approx. 5 encounters per parameter type) during the navigation task. The deliberate juxtaposition of these two archetypes is methodologically strategic rather than illustrative. By positioning the experimental environments at opposing ends of the configurational spectrum, the framework subjects itself to a stringent test of sensitivity to spatial integration and intelligibility. This design directly operationalizes the Configurational Primacy hypothesis: if statistically significant behavioral differences emerge between these layouts, they can be attributed to configurational properties rather than incidental geometric variation.

To ensure this distinction, the environments were generated using Esri CityEngine 2023 with a Weighted Distribution strategy rather than unconstrained randomness. This approach preserved the configurational logic distinguishing Type-A and Type-B morphologies while controlling the frequency and distribution of specific spatial features, such as street width variation and intersection types. Consequently, participants encountered structurally comparable levels of environmental complexity across conditions, allowing observed behavioral divergence to be robustly interpreted as a function of spatial configuration rather than idiosyncratic design artifacts.

3.4. Experimental Design: Stress, Cognitive Load, and Visual Depth

The experimental protocol uses a within-subjects factorial design (2 Morphologies × 2 Visibility Conditions). This setup enables direct comparison of behavioral responses across different spatial configurations while accounting for individual differences in navigational ability.

3.4.1. Stress Manipulation via Affordance Restriction

Cognitive load and stress were operationalized through a controlled manipulation of visibility, grounded in Gibson’s theory of affordances [

25] and in empirical evidence linking stress to disruptions in hippocampal-dependent spatial learning.

Daylight Condition (Baseline): The daylight condition serves as the control setting, maximizing visual depth and isovist properties. This allows participants to use distal landmarks and the global spatial structure for anticipatory route planning (

Figure 4).

Night Condition (Stress Induction): In contrast, the night condition mimics an emergency by limiting visibility to a 15 m radius, simulating scenarios like power outages or poor lighting. This significant narrowing of the isovist field blocks access to distant cues, forcing participants to depend only on nearby environmental features such as local junction layouts and immediate path widths/lengths. The underlying idea is that this reduction in perceptual information causes stress, promotes reliance on automatic, stimulus–response strategies for navigation, and hampers the ability to learn spatial relationships (

Figure 5).

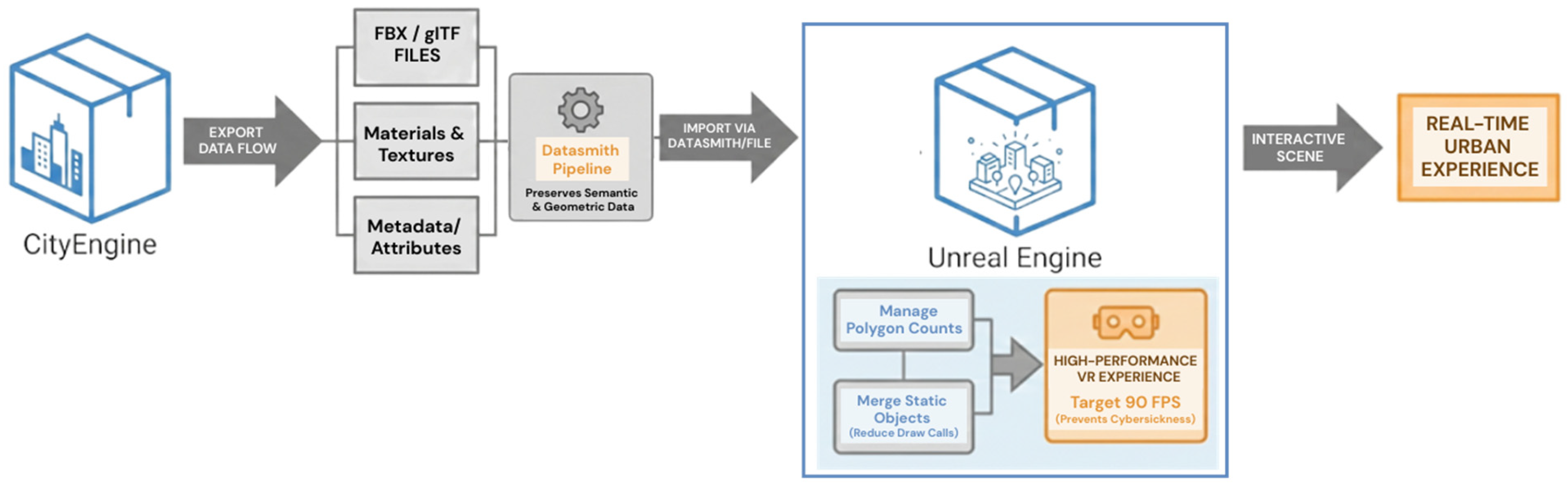

3.4.2. VR Integration and Technical Implementation

The procedurally generated environments were incorporated into Unreal Engine 5 (UE5) using the Datasmith workflow (see

Figure 6). To ensure that behavioral metrics accurately represented spatial cognition instead of technical latency, extensive optimization, such as polygon reduction and draw call minimization, was implemented to sustain a steady 90 fps performance.

For the night condition, stress was reinforced through a high-fidelity lighting simulation using UE5’s Lumen dynamic global illumination system:

Atmospheric Configuration: The BP_Sky_Sphere blueprint was set to night mode (Sun Height: −0.5), providing star and moon visibility.

Lighting Parameters: A Directional Light actor was configured as a moonlight source (main lighting source) with a Rotation of −40° (X-axis) and a low Intensity of 0.1 lux.

Volumetric Effects: Volumetric Scattering Intensity was set to 1.0 with Cast Shadows enabled to create realistic areas of total darkness and ambiguous depth. This lighting strategy was designed to deliberately fragment visual continuity, ensuring that observed hesitations or errors were direct consequences of the interaction between the morphology and the limited perceptual field.

3.4.3. Locomotion Interface Optimization: From Physical Treading to Teleportation

Following the pilot phase, a substantial methodological refinement was introduced to the locomotion interface. The experiment initially evaluated an omni-directional treadmill (Cyberith Virtualizer), which enabled continuous physical walking within a constrained area. However, usability tests revealed a pronounced cognitive interference: participants devoted significant effort to understanding the device’s motor mechanics, effectively “re-learning” how to walk, rather than engaging in environmental scanning and spatial decision-making. This physical adaptation period also prolonged the experiment and introduced fatigue as a confounding variable, ultimately undermining internal validity.

To eliminate these confounds, the locomotion mechanic was standardized to a teleportation-based navigation system. Although teleportation offers lower physical immersion than continuous treadmill walking and produces a more discrete movement flow, it substantially reduced motion sickness, minimized interface-related cognitive load, and removed physical fatigue from the behavioral data. This adjustment ensured that hesitation, errors, and navigational strategies could be attributed to morphological configuration and spatial intelligibility rather than the complexities of the locomotion hardware. In short, the decision traded a degree of physical realism for cleaner cognitive signals, thereby improving the interpretability and validity of the results.

3.5. Participants and Evaluation Metrics

3.5.1. Participant Selection and Criteria

The study sample consisted of 37 participants, recruited through a stratified volunteer sampling method to ensure balanced representation. The final cohort comprised 19 females (51.4%) and 18 males (48.6%), with ages ranging from 21 to 45 years (Mean = 28.3, SD = 5.7). The group consisted of volunteers from the university community, ensuring a balanced gender distribution and covering diverse age intervals to prevent clustering. This demographic profile reflects a young-adult to middle-aged urban population with high digital literacy. To ensure physiological suitability for VR, strict inclusion criteria were enforced: (1) normal or corrected-to-normal vision; (2) no self-reported history of vestibular disorders, epilepsy, or susceptibility to motion sickness; and (3) no prior exposure to the specific experimental environments. Prior to the study, all participants provided written informed consent regarding data privacy and safety procedures.

3.5.2. Justification of Sample Size: From Headcount to Decision Points

While the unique participant count was

N = 37, the study utilized a within-subjects repeated measures design, where participants navigated multiple scenarios (Type A, Type B, and Night conditions). After excluding incomplete trials due to physiological attrition, the final dataset comprises 85 valid experimental runs. For Agent-Based Model (ABM) calibration, the primary statistical power derives not from the number of agents, but from the quantity of behavioral interaction events. Across these 85 trials, the telemetry system recorded a total of 3907 discrete wayfinding decision points (ranging from 7 to 157 decisions per trial). This high-density behavioral dataset provides robust granular data for deriving algorithmic probability functions, aligning with contemporary standards in VR-based behavioral analytics [

7,

28].

3.5.3. Assessment Tools and Metrics

Behavioral performance was quantified using high-frequency log data exported directly from Unreal Engine 5. The classification of results was based on the following structured metrics:

Total Evacuation Time (TET): The primary metric measuring the duration (in seconds) from the start signal to the arrival at the designated safe zone.

Trajectory Length: The total distance traveled, used to calculate the ‘wayfinding efficiency index’ (distance traveled/shortest path).

Velocity Profile: Instantaneous speed recorded at 0.1s intervals. Sudden drops in velocity were flagged as ‘hesitation events’ or ‘orientation pauses’.

4. Results: Validating Configurational Primacy Through Behavioral Divergence

The results reveal a clear pattern of behavioral divergence across morphological configurations, indicating that spatial configuration is a critical determinant of navigational resilience, particularly under sensory deprivation. Analysis of time-to-completion and trajectory volatility shows that although both archetypes remain broadly navigable under optimal perceptual conditions, their performance diverges sharply when visibility is degraded. This divergence confirms a strong interaction between urban morphology and environmental stress.

4.1. The Interaction of Morphology and Visibility

Under daylight conditions, the performance gap between the organic (Type A) and orthogonal (Type B) archetypes was present but limited (see

Table 1). Statistical analysis indicates that this difference did not reach conventional significance thresholds (

p = 0.063). This suggests that when visual depth and global landmarks are perceptually accessible, participants can compensate for configurational complexity using survey knowledge and visual anticipation. In such conditions, deficits associated with irregular street layouts are partially mitigated by extended sightlines and the availability of distal cues, allowing wayfinding strategies to remain relatively stable across morphologies.

However, this equilibrium collapses under low-visibility nighttime conditions. A pronounced interaction between morphology and visibility was observed (F(1,59) = 47.3, p < 0.001), confirming that spatial configuration becomes the dominant predictor of evacuation performance when perceptual access is constrained.

Orthogonal Resilience: In the grid layout, participants maintained relatively efficient navigation despite restricted visibility, with a mean completion time of 2.03 min and a comparatively stable standard deviation (SD ± 1.33). This resilience reflects a “cognitive anchor effect”: the predictable linearity and consistent junction geometry of the grid preserved navigational logic even without global visual cues. Local spatial regularities provided sufficient information for anticipatory movement, enabling participants to infer direction and maintain orientation under stress.

Organic Deterioration: By contrast, performance in the organic configuration deteriorated substantially under identical conditions. Mean completion time increased to 2.85 min, accompanied by the highest behavioral volatility observed in the study (SD ± 2.08). The disproportionate expansion of variance signals extreme behavioral unpredictability; some participants experienced acute disorientation, while others became trapped in locally coherent but globally inefficient loops.

Quantitatively, egress time in the organic archetype degraded by 67%, compared to only a 15% increase in the orthogonal configuration. This sharp contrast provides robust empirical support for the concept of configurational primacy: as sensory information decreases, the structural logic of the street network increasingly dictates survival outcomes.

4.2. Location-Specific Behavioral Signatures

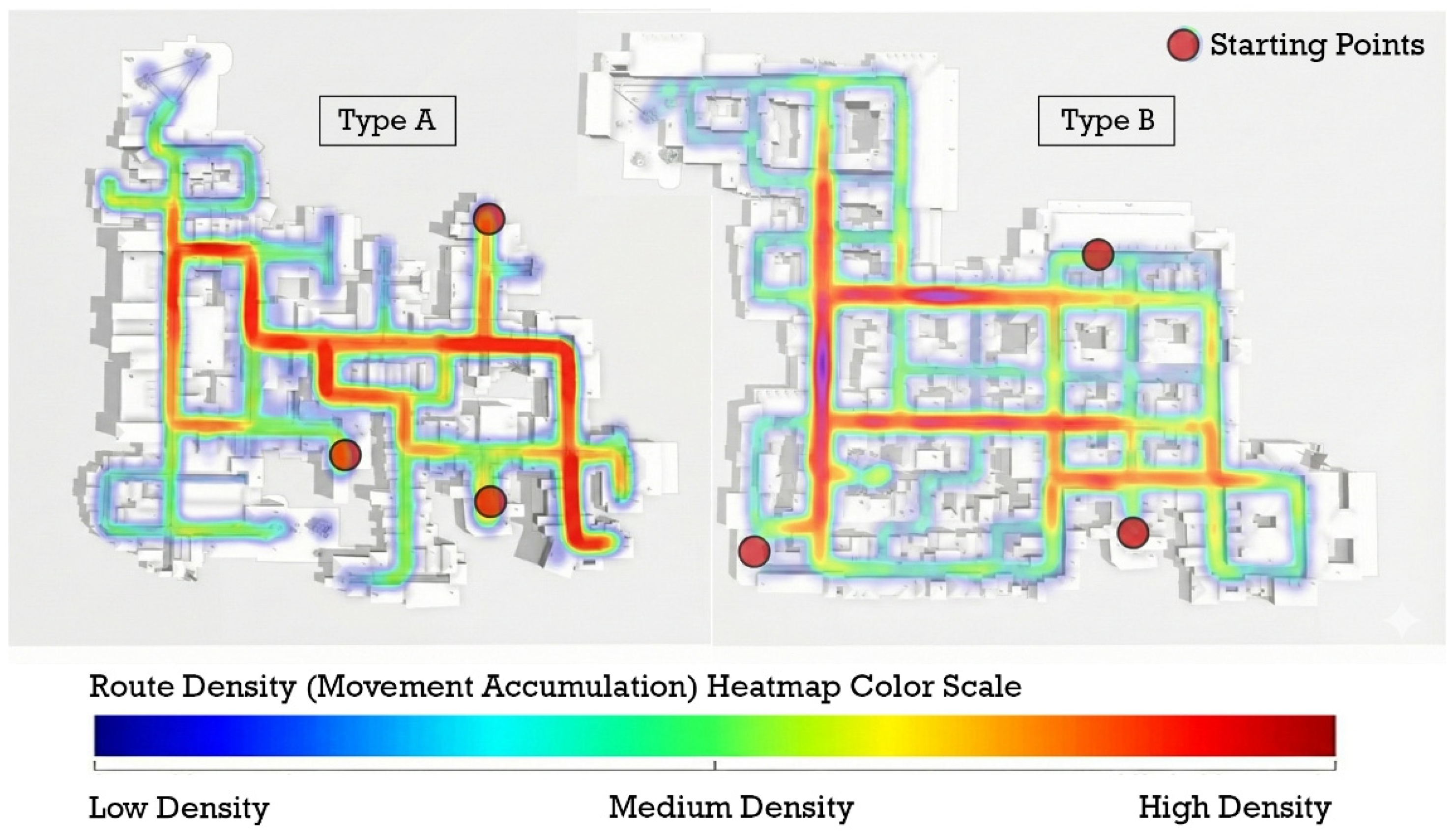

Spatially explicit behavioral analysis reinforces the causal link between morphological parameters and navigation performance. To visualize the aggregate impact of urban morphology on wayfinding strategies, participant locomotion data were aggregated into density heatmaps (see

Figure 7). These visualizations reveal a fundamental divergence in how movement flows through the two archetypes.

4.2.1. Trajectory Divergence: Linear vs. Reactive Flow

The heatmap for the Orthogonal Configuration (Type B) exhibits high axial linearity. Movement patterns are sharply defined and concentrated along the longest lines of sight, confirming that participants utilized the grid’s “visual corridors” to accelerate decision-making. The lack of scattered trajectories outside the main axes suggests a high degree of navigational certainty; participants identified the optimal path early and adhered to it. This supports the “Cognitive Anchor” effect, where geometric regularity acts as a navigational rail.

In contrast, the Organic Configuration (Type A) reveals a trajectory pattern strictly constrained by local geometry. Movement flows are forced into sinuous paths dictated by building envelopes rather than chosen lines of sight. Unlike the grid, where movement is “projective” (moving toward a distant goal), movement in the organic layout appears “reactive” (responding to the immediate wall or turn).

4.2.2. Morphological Determinants: Topology and Volumetrics

While the red markers in the visualizations indicate fixed starting points, the density of the trajectories (represented by the spectral heat gradient along the paths) and the underlying telemetry data reveal how morphology dictated movement.

Impact of Junction Topology: Behavioral telemetry (specifically velocity drops) reveals that hesitation events were not randomly distributed but correlated with junction geometry. In Archetype A, the high frequency of T-junctions (T-ratio: 0.8) forced participants to make sharp 90-degree reorientations without visual preview. The trajectory heatmaps show that movement at these nodes is constrained and reactive. Conversely, the prevalence of X-junctions (X-ratio: 0.4) in Archetype B provided visual continuity, allowing participants to scan upcoming segments before arriving at the decision point, resulting in more fluid and linear trajectory traces.

Volumetric Influence: Furthermore, trajectory volatility was most pronounced in street segments characterized by high vertical rugosity (varying building setbacks and heights). Participants were observed slowing down in these “canyon-like” segments, likely attempting to derive orientation cues from the complex building fabric when global sightlines were unavailable.

4.2.3. Heuristic Failure

The analysis also highlights morphology-dependent variations in heuristic utility. The “direction-of-destination” heuristic, which relies on Euclidean alignment toward a perceived goal, proved effective in the orthogonal configuration because of the strong correspondence between local directionality and the global network structure. In the organic layout, however, this same heuristic systematically produced wrong turns, as the Euclidean direction frequently diverged from the topologically shortest path.

This divergence highlights a critical insight for ABM calibration: the same decision heuristics lead to radically different outcomes depending on the configuration. Consequently, the inability of the Type-A network to maintain consistent local-to-global logic caused cascading navigational errors, emphasizing the need for behavior models that account for morphological differences.

5. Discussion: Toward a Theory of Resilient Morphology

5.1. Structural Legibility as a Core Determinant of Resilience

This study demonstrates that structural legibility is not a secondary aesthetic attribute but a fundamental determinant of disaster resilience. The orthogonal grid did more than enable faster evacuation; it consistently suppressed behavioral variance, producing navigation patterns that were stable, predictable, and therefore manageable under stress. This stability can be directly attributed to the prevalence of X-junctions (as observed in Archetype B), which allowed participants to visually scan upcoming path segments before commitment. In contrast, the organic configuration exhibited a sharp loss of behavioral coherence under degraded visibility, revealing a latent vulnerability typical of historic urban cores when global perceptual cues collapse. The high frequency of T-junctions and significant vertical rugosity in Archetype A acted as ‘cognitive barriers,’ forcing participants to rely on reactive navigation rather than anticipatory planning. These results indicate that risk in such environments is not simply a function of population density or exit width, but of how reliably local spatial cues support orientation when cognitive resources are constrained.

By coupling immersive VR experimentation with data-driven ABM, the proposed pipeline moves beyond static, compliance-based evaluations toward the dynamic “stress testing” of urban form. Rather than assuming idealized user behavior, the framework assesses whether a spatial configuration remains legible when visibility collapses or users operate under heightened cognitive load. This shift reframes evacuation performance as an emergent property of spatial structure interacting with human perception, rather than as a purely operational or procedural problem.

5.2. Reframing Panic: Stress as a Spatial Variable

A key theoretical contribution of this study is redefining navigational failure. The results clarify that what is commonly called “panic” during evacuation modeling is not just a psychological response; instead, it is a spatially triggered condition caused by low intelligibility combined with physiological stress. The pronounced velocity drops recorded in the telemetry, and visualized as high-density segments in the heatmaps (

Section 4.2), provide empirical proof of this phenomenon: ‘panic’ manifested physically as freezing behavior specifically at nodes with ambiguous local affordances. In this context, stress acts as a spatial variable, modulated by configuration, visibility, and junction geometry. Agent rules from this framework are grounded in actual human responses observed in controlled, realistic settings, making them different from purely theoretical social-force assumptions. This clear behavioral specification guarantees that irrational behaviors like looping or freezing are not simply arbitrary parameters but validated results of particular physical conditions. As a result, the framework helps researchers improve urban design for more reliable human behavior, pinpointing specific spatial changes to prevent disorientation before a disaster occurs.

5.3. From Empirical Data to Algorithmic Parameterization

The detailed resolution of VR-derived behavioral data enables a significant move from assumption-based agent specifications to truly data-driven agent-based modeling. Instead of relying on generic heuristics or fixed hesitation constants, the observed locomotion trajectories and stress-related navigation patterns offer an empirical foundation for directly inferring agent decision logic from human behavior.

These metrics enable modeling confusion, hesitation, and route instability as conditional phenomena that arise under specific combinations of spatial complexity and perceptual constraints. The agents not only navigate networks efficiently but also exhibit characteristic irrationalities, pauses, and maladaptive behaviors typical of complex urban environments during low-visibility evacuations. Because these behaviors are parameterized using universal morphological measures, such as connectivity, integration, and isovist properties, rather than site-specific features, the framework is highly transferable. It offers a scalable tool for pre-disaster resilience assessments applicable in a wide range of urban settings, from informal settlements to planned developments.

6. Limitations and Methodological Constraints

While this study effectively establishes a framework connecting urban morphology with behavioral analytics, it also has certain limitations in experimental design and sampling. These restrictions represent intentional trade-offs, prioritizing internal validity and controlled experiments over wider ecological applicability.

6.1. Sample Size and Physiological Attrition

A total of 37 participants completed the baseline Day condition trials (Type A and Type B). The Night condition, involving sensory deprivation, was conducted following strict ethical guidelines that allow participants to withdraw at any time. As a result, only 17 participants took part in this phase. These participants were evenly distributed across different morphological conditions to maintain balance, though minor variations occurred due to physiological attrition. Data from individuals who experienced cybersickness or chose to stop the session early were excluded to ensure reliable behavioral measurements. The remaining resilient participants imply that the observed performance declines are conservative; the actual effects on the broader population might be even greater.

6.2. Sensory Attenuation and Ecological Validity

While the VR environment offers high visual accuracy, it cannot fully replicate the multisensory experience of a disaster. Essential physical stressors such as smoke/dust inhalation, heat, or physical exertion were intentionally omitted in this study due to ethical concerns. Consequently, stress induction was primarily cognitive and sensory, structured through a countdown ticking sound to induce a sense of panic, leading to confusion rather than instinctive fear. This reduction suggests that the observed decrease in wayfinding performance may underestimate real-world implications. In actual emergencies, increased physiological stress likely increases hesitation and errors, indicating that the behavioral metrics presented here are conservative lower bound estimates.

6.3. Demographic Scope

The participant pool mainly consists predominantly of a university community with high digital literacy and cognitive ability. Although suitable for proof-of-concept tests, this group does not reflect the full range of vulnerability found in the general population. Behavioral responses may vary significantly for children, seniors, or those with mobility issues. Broadening demographic diversity is essential to make these insights applicable for inclusive policy-making.

6.4. Morphological Idealization

This study used two urban archetypes, Type A and Type B, as idealized extremes to create clear experimental contrast. In reality, urban fabrics often show hybrid or transitional forms that blur these distinctions. While employing such extremes was essential for testing the framework’s sensitivity and isolating configurational effects, applying these behavioral rules to actual cities will need additional adjustment to accommodate intermediate and mixed morphologies.

7. Conclusions

This study addresses the critical data scarcity in agent-based evacuation models by proposing a reproducible framework that combines procedural environment creation with VR-based behavior calibration. By considering urban morphology as an independent variable, the study shows that spatial configuration is more than just a static container for movement; it actively influences resilience, especially under degraded sensory conditions.

The results support the Configurational Primacy hypothesis: in daylight, navigation relies on global visual cues that conceal the dangers of irregular layouts. However, in low-visibility situations, this compensation fails, and the street network’s underlying structure determines performance. Crucially, the study identifies that specific morphological traits, namely, high T-junction ratios and vertical rugosity, serve as primary predictors of navigational failure. The organic and irregular morphology led to a 67% longer evacuation time and greater behavioral variability compared to the orthogonal grid, confirming that “intelligibility” is not abstract, but functionally dependent on measurable morphological ratios such as intersection topology (X vs. T) and visual connectivity.

Future Directions

Future research will prioritize three key axes of expansion:

Demographic Inclusivity: Expanding the protocol to include diverse user groups such as the elderly and individuals with mobility impairments to better understand different vulnerabilities and develop more inclusive evacuation strategies.

Social Integration: Adding multi-agent interactions and non-player characters (NPCs) in the VR setup to explore how spatial comprehension influences social behaviors like herding or following a leader.

Visual Attention Analysis (Eye-Tracking): While this study successfully correlated morphological configuration with locomotion performance, the specific influence of 3D volumetric parameters (e.g., building height, aspect ratio, and façade porosity) on visual attention remains to be quantified. Future iterations will integrate eye-tracking telemetry to map gaze fixations. This will allow researchers to determine whether participants under stress prioritize vertical cues (e.g., skyline contrast) or horizontal affordances (e.g., street corners) during wayfinding, thereby validating the impact of the volumetric parameters defined in this framework.

Algorithmic Implementation: The goal is to convert these empirical data into a structured “Behavioral Library” for ABM platforms like GAMA, Anylogic or NetLogo. By incorporating morphology-sensitive hesitation and error functions into simulation agents, we aim to develop evacuation models that are both spatially precise and behaviorally realistic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K., S.K. and F.A.; methodology, D.K.; software, D.K.; validation, D.K. and S.K.; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, D.K.; resources and data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K.; visualization, D.K.; supervision, S.K., F.A. and C.J.v.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK), 2214-A (International Research Fellowship Programme for PhD Students), grant number 1059B142300024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Social and Humanities Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Istanbul Technical University (protocol code 535 and date of approval 15 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participant(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions regarding participant telemetry logs.

Acknowledgments

The authors declare that this work is part of a doctoral thesis project carried out at Istanbul Technical University and developed in collaboration with the Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (ITC) and the Faculty of Behavioural, Management and Social Sciences (BMS) at the University of Twente, through the TÜBİTAK 2214-A scholarship. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Large Language Models (LLMs) for translation, editing, and language refinement purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| UE5 | Unreal Engine 5 |

| CGA | Computer Generated Architecture |

| LOD | Level of Detail |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| HISM | Hierarchical Instanced Static Mesh |

| PCG | Procedural Content Generation |

| ABM | Agent-Based Model |

| HITL | Human-in-the-Loop |

References

- Hillier, B. Spatial Sustainability in Cities: Organic Patterns and Sustainable Forms. In Proceedings of the 7th International Space Syntax Symposium; Royal Institute of Technology (KTH): Stockholm, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, L.; Colding, J. Toward an Integrated Theory of Spatial Morphology and Resilient Urban Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defining Urban Social Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, G.P.D.P.; Kieu, M.; Zou, Y.; Dirks, K. Agent-Based Simulation for Pedestrian Evacuation: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 111, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Grimm, V.; Bai, Y.; Sullivan, A.; Turner, B.L.; Malleson, N.; Heppenstall, A.; Vincenot, C.; Robinson, D.; Ye, X.; et al. Modeling Agent Decision and Behavior in the Light of Data Science and Artificial Intelligence. Environ. Model. Softw. 2023, 166, 105713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppenstall, A.; Crooks, A.; Malleson, N.; Manley, E.; Ge, J.; Batty, M. Future Developments in Geographical Agent-Based Models: Challenges and Opportunities. Geogr. Anal. 2021, 53, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juřík, V.; Uhlík, O.; Snopková, D.; Kvarda, O.; Apeltauer, T.; Apeltauer, J. Analysis of the Use of Behavioral Data from Virtual Reality for Calibration of Agent-Based Evacuation Models. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, R.; Rebelo, F.; Vilar, E.; Noriega, P. Human Interaction with Virtual Reality: Investigating Pre-Evacuation Efficiency in Building Emergency. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irsyad, H.A.W.; Hitoshi, N. Flood Disaster Evacuation Route Choice in Indonesian Urban Riverbank Kampong: Exploring the Role of Individual Characteristics, Path Risk Elements, and Path Network Configuration. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 81, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Mo, Y.; Kalasapudi, V.S. Status Quo and Challenges and Future Development of Fire Emergency Evacuation Research and Application in Built Environment. ITcon 2022, 27, 781–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, O.; Dawson, R.J. Flood Evacuation in Informal Settlements: Application of an Agent-Based Model to Kibera Using Open Data. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienfuegos, R.; Álvarez, G.; León, J.; Urrutia, A.; Castro, S. Analysis of the Effects of Urban Micro-Scale Vulnerabilities on Tsunami Evacuation Using an Agent-Based Model—Case Study in the City of Iquique, Chile. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 24, 1485–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, B.; Dunn, S.; Pearson, C.; Wilkinson, S. Improving Human Behaviour in Macroscale City Evacuation Agent-Based Simulation. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 60, 102289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, A.; Gwynne, S.M.V. The Collection and Compilation of School Evacuation Data for Model Use. Saf. Sci. 2016, 84, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahouti, A.; Lovreglio, R.; Dias, C.; Kuligowski, E.; Gai, G.; La Mendola, S. Investigating Office Buildings Evacuations Using Unannounced Fire Drills: The Case Study of CERN, Switzerland. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 125, 103403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ling, W.; Cheng, F.; Deng, X.; Wei, X.; Wang, H.; Song, J.; Wei, S. Multi-Spatial-Parametric Evacuation Modeling for Data Mining of Route Selection in University Libraries: An Immersive VR-Based Approach. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2026, 69, 103922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahlawi, R.Y.; Akbari, V.; Lawson, G. A Systematic Review of Methodologies for Human Behavior Modelling and Routing Optimization in Large-Scale Evacuation Planning. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 110, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Lu, W.; Wang, L. Experimental Study on Evacuation Behaviour of Children in a Three-Storey Kindergarten. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lovreglio, R.; Nilsson, D. Modelling and Interpreting Pre-Evacuation Decision-Making Using Machine Learning. Autom. Constr. 2020, 113, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaioli, G.; Domingos, T.; Teixeira, R.F.M. A Framework for Data-Driven Agent-Based Modelling of Agricultural Land Use. Land 2023, 12, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lei, J.; Xiu, C.; Li, J.; Bai, L.; Zhong, Y. Analysis of Spatial Scale Effect on Urban Resilience: A Case Study of Shenyang, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovreglio, R.; Dillies, E.; Kuligowski, E.; Rahouti, A.; Haghani, M. Exit Choice in Built Environment Evacuation Combining Immersive Virtual Reality and Discrete Choice Modelling. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Rebelo, F.; He, R.; Noriega, P.; Vilar, E.; Wang, Z. Using Virtual Reality to Explore the Effect of Multimodal Alarms on Human Emergency Evacuation Behaviors. Virtual Real. 2025, 29, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dang, P.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, W.; Hu, Y.; You, J. The Impact of Spatial Scale on Layout Learning and Individual Evacuation Behavior in Indoor Fires: Single-Scale Learning Perspectives. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 38, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, H.; Mortimer, M.; Horan, B. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Virtual Reality for Safety-Relevant Training: A Systematic Review. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 2839–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y. Virtual Reality Simulation for Disaster Preparedness Training in Hospitals: Integrated Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e30600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S. Streets & Patterns, 1st ed.; Spon Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-203-58939-7. [Google Scholar]

- Moussaïd, M.; Kapadia, M.; Thrash, T.; Sumner, R.W.; Gross, M.; Helbing, D.; Hölscher, C. Crowd Behaviour during High-Stress Evacuations in an Immersive Virtual Environment. J. R. Soc. Interface 2016, 13, 20160414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |