Food Waste in Hospitals: Determining Factors and Sustainable Strategies for Mitigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Narrative Review

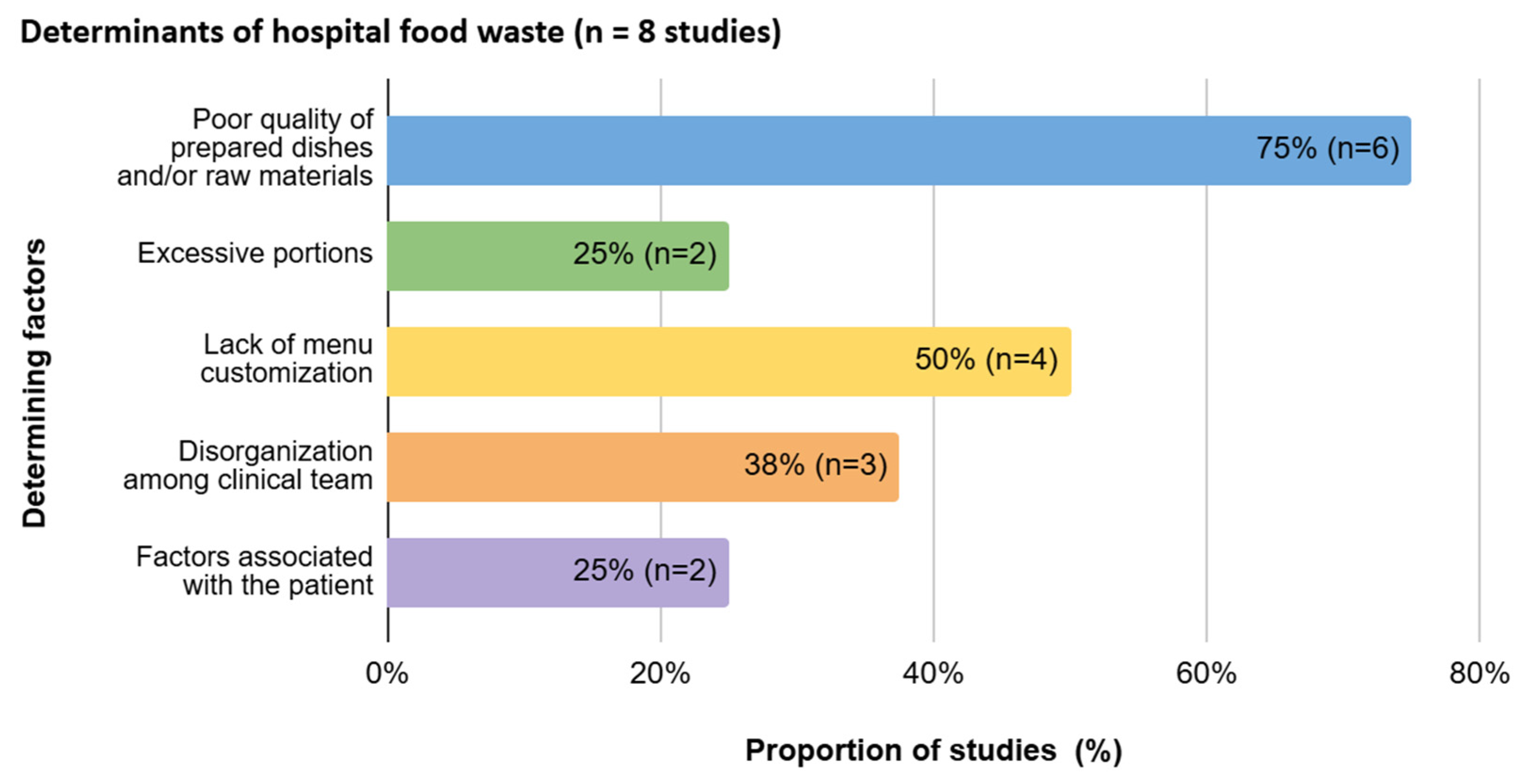

3.1.1. Determinants of Hospital Food Waste

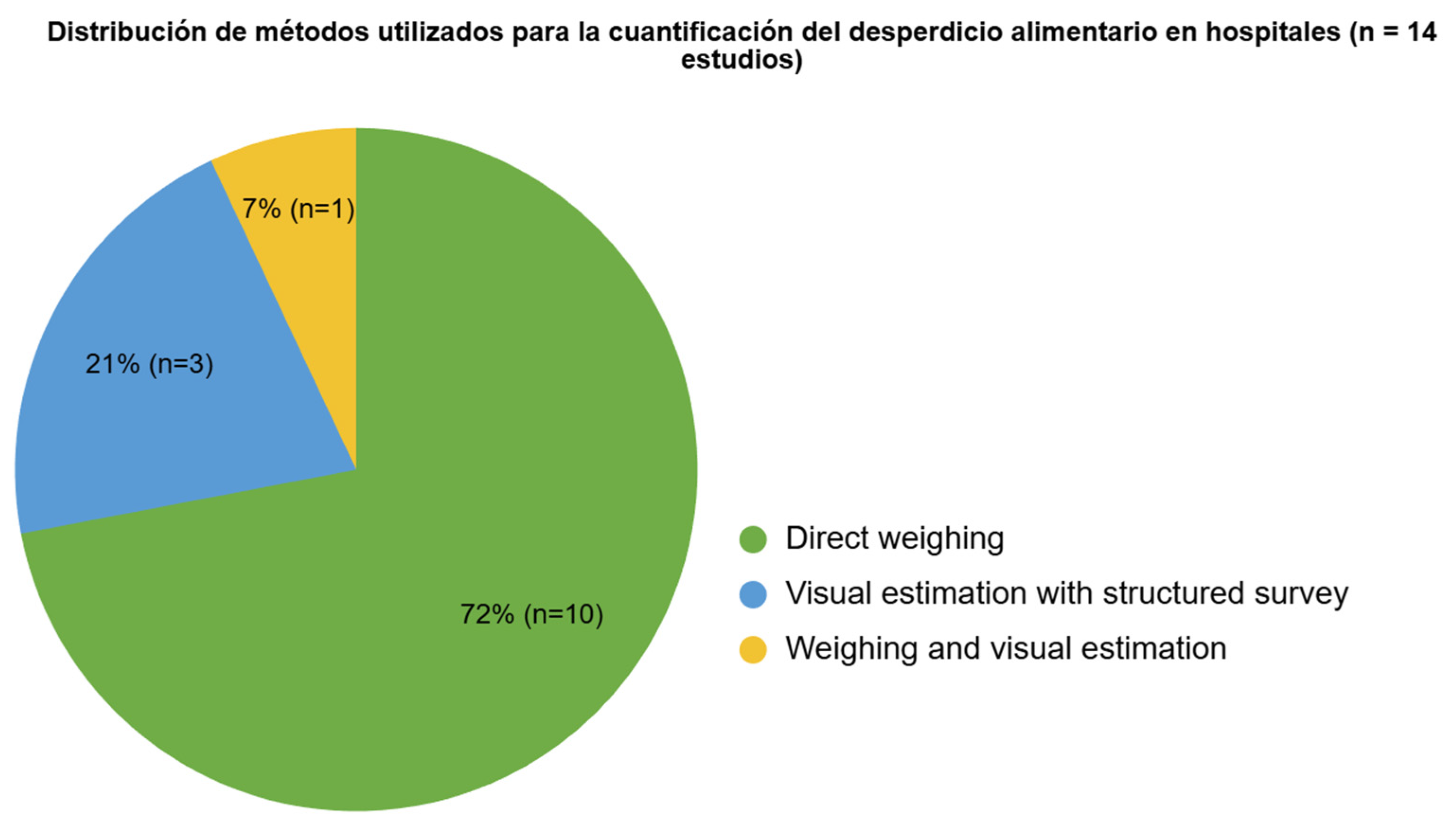

3.1.2. Methods for Quantifying Hospital Food Waste

3.1.3. Mitigation Strategies for Reducing Hospital Food Waste

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis

3.2.1. Temporal Evolution of Publications Based on Keywords

3.2.2. Scientific Article Publications by Country and International Collaborations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FLW | Food loss and waste |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| MCP | International collaborations |

| PCFW | Post-consumer food waste |

| SCP | National collaborations |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme |

References

- FAO. Food Losses and Waste in the World: Scope, Causes and Prevention. 2012. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/i2697s/i2697s00.htm (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition. 2023. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2023_Spanish.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Coudard, A.; Sun, Z.; Behrens, P.; Mogollón, J.M. The Global Environmental Benefits of Halving Avoidable Consumer Food Waste. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13707–13716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Srivastava, S.; Gupta, A.; Singh, G. Food wastage and consumerism in circular economy: A review and research directions. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 2561–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzby, J.C.; Hodan, F. The Estimated Amount, Value, and Calories of Postharvest Food Losses at the Retail and Consumer Levels in the United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 2014. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details?pubid=43836 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Bhattacharya, S.; Chatterjee, S.M.; Sachdev, B.K.; Seth, A. Food waste management: A roadmap to reduce food poverty and food loss with the rise in climate change and poverty. Galaxy Int. Interdiscip. Res. J. 2021, 9, 536–543. Available online: https://internationaljournals.co.in/index.php/giirj/article/view/392 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Durán-Sandoval, D.; Durán-Romero, G.; López, A.M. Assessing Food Loss and Waste in Chile: Insights for Policy and Sustainable Development Goals. Resource 2024, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredes, C.; Moya, J.L.; Jara, M.; Reyes-Jara, A. Reduction, reuse, and recycling: A critical review of scientific knowledge on food loss and waste in Chile. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2023, 50, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/es/resources/informe/indice-de-desperdicio-de-alimentos-2021 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Williams, P.; Walton, K. Plate waste in hospitals and strategies for change. e-SPEN Eur. E J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 6, e235–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.; Goodwin, D.; Porter, J.; Collins, J. Food and food-related waste management strategies in hospital food services: A systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 80, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bakel, S.I.J.; Moonen, B.; Mertens, H.; Havermans, R.C.; Schols, A.M.W.J. Personalization in mitigating food waste and costs in hospitalization. Clin Nutr. 2024, 43, 2215–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoteit, M.; Antar, E.; Malli, D.; Fattouh, F.; Khattar, M.; Baderddine, N.; El Cheikh, J.; Chalak, A.; Abiad, M.G.; Hassan, H.F. A review on hospital food waste quantification, management and assessment strategies in the eastern Mediterranean region. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsería-Rodríguez, L.; Bejarano-Roncancio, J.; Medina-Parra, J.; Merchán-Chaverra, R.; Cuéllar-Fernández, Y. Tools to identify consumption and waste of the hospital diet. Systematic Review. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2022, 49, 268–282. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-75182022000200268&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en (accessed on 10 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.; Porter, J. Quantifying waste and its costs in hospital foodservices. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 80, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu’awanah, H.; Ulfa, M.; Rajikan, R.; Saygili, M.; Akca, N. Hospital Food Waste Trends: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Health Sci. Med. Res. 2024, 43, 20241069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.; Collins, J. A Qualitative Study Exploring Hospital Food Waste from the Patient Perspective. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bux, C.; Zizzo, G.; Amicarelli, V. A combined evaluation of energy efficiency, customer satisfaction and food waste in the healthcare sector by comparing cook-hold and cook-chill catering. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anari, R.; Amini, M.; Nikooyeh, B.; Ghodsi, D.; Neyestani, T. Why patients discard their food? A qualitative study in Iranian hospitals. Int. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2023, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carino, S.; Collins, J.; Malekpour, S.; Porter, J. Environmentally sustainable hospital foodservices: Drawing on staff perspectives to guide change. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, S.; Pelullo, C.; Attena, F. Patient evaluation of food waste in three hospitals in southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuleihan, K.; Stillman, K.; Hakimian, J.; Sarkar, K.; Ballesteros, J.; Almario, C.; Shirazipour, C. Identifying solutions to minimize meal tray waste: A mixed-method approach. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2024, 62, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, B.; Robinson, E.; Gordon, R. Investigating food waste generation at long-term care facilities in Ontario. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 2902–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemah, T.; Nur Adilah, Z.; Sabaianah, B.; Zurinawati, M.; Aslinda Mohd, S. Plate Waste in Public Hospitals Foodservice Management in Selangor, Malaysia. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriz-Jorquiera, M.; Acuna, J.; Rodríguez-Carbó, M.; Zayas-Castro, J. Hospital food management: A multi-objective approach to reduce waste and costs. Waste Manag. 2024, 175, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liwinski, T.; Bocek, I.; Schmidt, A.; Kowalinski, E.; Dechent, F.; Rabenschlag, F.; Moeller, J.; Sarlon, J.; Brühl, A.; Nienaber, A.; et al. Sustainability initiatives in inpatient psychiatry: Tackling food waste. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1374788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Saraiva, C.; Esteves, A.; Gonçalves, C. Evaluation of hospital food waste—A case study in Portugal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.; Qattan, M.; Alhaji, J. Towards sustainable food services in hospitals: Expanding the concept of “plate waste” to “tray waste”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Malefors, C.; Bergström, P.; Eriksson, E.; Osowski, C. Quantities and Quantification Methodologies of Food Waste in Swedish Hospitals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, L.; Hernández, C.; Santos, D.; Garayoa, R.; García, L.; Urdangarín, C.; Vitas, A. Hospital Plate Waste Assessment after Modifications in Specific Dishes of Flexible and Inflexible Food Ordering Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, C.; Park, S.; Musicus, A.; Agins, J.; Gan, J.; Held, J.; Horrocks, A.; Bragg, M. Waste generation and carbon emissions of a hospital kitchen in the US: Potential for waste diversion and carbon reductions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D. Food Waste: A Healthcare Study. Pūhau Ana Te Rā Tailwinds 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yona, O.; Goldsmith, R.; Endevelt, R. Improved meals service and reduced food waste and costs in medical institutions resulting from employment of a food service dietitian—A case study. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2020, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Dora, M.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Iacovidou, E. Opportunities, challenges and trade-offs with decreasing avoidable food waste in the UK. Waste Manag. Res. 2021, 39, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Maccauro, V.; Cintoni, M.; Cambieri, A.; Fiore, A.; Zega, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M. Hospital Services to Improve Nutritional Intake and Reduce Food Waste: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manimaran, S.; Razalli, N.; Abdul Manaf, Z.; Mat Ludin, A.; Shahar, S. Strategies to Reduce the Rate of Plate Waste in Hospitalized Patients: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzipavlou, M.; Karayiannis, D.; Chaloulakou, S.; Georgakopoulou, E.; Poulia, K. Implementation of sustainable food service systems in hospitals to achieve current sustainability goals: A scoping review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 61, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, C.; Lipinski, B.; Robertson, K.; Dias, D.; Gavilan, I.; Gréverath, P.; Ritter, S.; Fonseca, J.; van Otterdijk, R.; Timmermans, T.; et al. Food Loss and Waste Accounting and Reporting Standard. 2016. Available online: https://flwprotocol.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/FLW_Standard_final_2016.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies that focused on:

|

| Determining Factors | Description | Main Results | Population or Sample | Country | Type of Study | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of appetite and interest in food on the part of the patient. Poor quality of raw materials and excessive quantity of food. Lack of personalization of menus. | Low appetite or lack of interest in food due to medical conditions or personal preferences. Includes aspects such as taste, esthetics, lack of variety, and excessive portions. Standardized menus. | Reduced appetite, food quality and quantity, and lack of personalization were identified as contributing factors to food waste. | n = 40 hospitalized patients. | Australia | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | Porter and Collins [17] |

| Poor quality of raw materials and poor patient perception of food. | Bad smell, bland taste, and inadequate texture affect food acceptance. | 22.63% indicated that the food had a bad smell, 19.26% rated it as tasteless, and 17.23% considered it overcooked. | n = 984 hospitalized patients. | Italy | Quantitative (measurements and satisfaction surveys) | Bux et al. [18] |

| Disease-specific factors. Poor quality of prepared meals. Excessive portion sizes. | Acute and chronic diseases limit adequate food intake. Poor taste of food, presentation, and cooking method. Excessive portions. | Anorexia, nausea, and personal dietary restrictions were identified as causes of waste. Hospital food was not appropriate according to patients’ perceptions. More food is delivered than necessary, as indicated by directors. | n = 12 hospitalized patients n = 9 nurses n = 3 hospital directors n = 3 food suppliers n = 8 nutritionists n = 13 kitchen staff | Iran | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | Anari et al. [19] |

| Lack of menu customization and anticipation of requests. Disorganization among clinical staff. | Standardized menus and requests made by dietitians 24 h in advance. Inefficient coordination between the clinical team and food services, generating extra tray requests. | The time between ordering food and delivery, as well as the variety of food options, were identified as factors contributing to food waste. Poor communication between the ward and food service staff about a patient’s low consumption often resulted in food waste. | n = 8 nurses n = 2 hospital directors n = 6 food suppliers n = 9 nutritionists n = 8 production staff | Australia | Generic qualitative (open-ended questions) | Carino et al. [20] |

| Poor quality of prepared meals. Lack of menu customization | Poor quality of food served and raw materials used. Lack of menu variety according to patients’ individual preferences | 56.4% of reasons for food rejection. | n = 713 hospitalized patients | Italy | Quantitative cross-sectional study | Schiavone et al. [21] |

| Disorganization among clinical staff. Lack of menu customization and inflexible schedules. Poor quality of prepared meals. | Inefficient coordination between the clinical team and food services, leading to extra tray requests. Standard menus versus patient preferences. Poor taste of meals. | “Patient discharge” accounts for 43% of total food tray waste. Flexibility in schedules and adaptation to patient preferences at mealtimes minimizes food waste. Patients do not like the taste or aroma of the food. like the food, its taste, or its aroma. | n = 16 hospitalized patients n = 6 nurses n = 2 hospital directors n = 2 nutritionists n = 2 kitchen staff n = 10 experts in the field | United States | Sequential explanatory mixed-methods design. Quantitative and qualitative methods (semi-structured interviews) | Fuleihan et al. [22] |

| Disorganization among clinical staff. | Overproduction of meals for patients. | The researchers determined that this was the largest source of food waste, accounting for 45.5% of the total sent. | Observation of n = 336 patient meal trays | Canada | Exploratory study. Quantitative methods and field observations | McAdams et al. [23] |

| Poor quality of prepared meals. | Poor taste and temperature of meals. | Researchers concluded that temperature and taste directly influence food waste, p < 0.05 | n = 256 hospitalized patients | Malaysia | Quantitative study (structured questionnaire) | Chemah et al. [24] |

| Quantification Method | Description | Main Results | Identification of Main Sources of Waste | Population or Sample | Country | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct weighing. | Direct quantification of the weight of food waste generated by dishes not consumed by patients. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were counted. | An average of 81 g of food waste per meal served, equivalent to an average waste per plate of between approximately 12% and 21%. | Lunch is the meal that generates the most waste. | n = 4362 meals for adult inpatients | Netherlands | van Bakel et al. [12] |

| Visual estimation with structured survey | Meals categorized using a circle divided into four equal segments. Average weights of dishes served are used. Lunch and dinner were evaluated. | 141 g of food waste per meal served on average, equivalent to an average waste per dish of between approximately 11 and 29%. | Dinner was identified as the meal that generates the most waste. | n = 984 hospitalized patients. | Italy | Bux et al. [18] |

| Direct weighing. | Direct quantification of the weight of food waste generated by dishes not consumed by patients. | Patients in the pediatric ward generate an average of 200 g of food waste per day, which is equivalent to 35.43% of their meals. Adult patients generate an average of 160 to 190 g of waste per day. | The research mentions the vegetarian diet as the one that generated the most waste. | n = 1 hospital with a capacity of 1000 beds | United States | Arriz-Jorquiera et al. [25] |

| Direct weighing. | Direct quantification of the weight of food waste generated by patients in a psychiatric hospital. | A total of 4089 kg of waste was determined from the total sample, where 818 kg, or 20% of the waste, was equivalent to meals that were not “touched” by patients. | “Untouched” meals, lunch, and dinner constitute the meal times with the most waste. | n = 25,540 meals served in a psychiatric center with 277 beds | Switzerland | Liwinski et al. [26] |

| Direct weighing and visual estimation. | Direct quantification of the weight of solid food waste and visual inspection of liquid waste (soups). | On average, total food waste from the plate served was 56.4%. Only the lunch service was evaluated. | Pediatric service had the highest percentage of food waste per plate (67.1%). Vegetables were the least consumed category in this group (65%). The highest waste occurred on the day of hospital admission in adults and pediatrics. | n = 321 meals from pediatric and adult inpatients | Portugal | Gomes et al. [27] |

| Direct weighing. | Direct quantification of the weight of food waste generated by dishes not consumed by patients. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were counted. | The average daily food waste per patient was 410 g. | Dinner was identified as the meal that generated the most food waste, with an average of 160 g per day. | n = 939 meal trays for hospitalized adult patients (solid diets only) | Saudi Arabia | Alharbi et al. [28] |

| Visual estimation with structured survey. | Main question: What percentage of your meals did you consume? A 5-point Likert scale was used. | The average daily food waste per patient was 41.6% of the food served. Women wasted more food than men (59.1% vs. 38.2%). | Vegetables and potatoes were the foods with the highest waste, accounting for 55.0% of the total served. | n = 713 hospitalized patients | Italy | Schiavone et al. [21] |

| Direct weighing | Quantification of waste weight in three categories: food waste, service waste, and kitchen waste. | The average waste was 111 g per person per meal, distributed as 42% food waste, 36% service waste, and 22% kitchen waste. | Most waste is generated at lunch and dinner. | n = 17 hospitals | Sweden | Eriksson et al. [29] |

| Direct weighing. | Direct quantification of the weight of food waste generated by dishes not consumed by patients. | On average, 29.5% of the food served was discarded, with chicken and fish being the most critical. | Milk, chicken, and fish at lunch generated more than 25% of food waste and were classified as critical dishes, with the à la carte menu having the lowest waste percentages. | n = 4641 meals | Spain | Paiva et al. [30] |

| Direct weighing. | Quantification of total waste weight in three categories: food waste on plates, undelivered trays, and packaging. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner were counted. | On average, 502.1 kg/day of food waste was generated, with 45% coming from plates (food not consumed by patients), 20% from trays (not delivered), and 35% from packaging. | Lunch is the meal that generates the most waste, with 95.3 kg/day of food waste. The average number of unused trays per day in these hospitals is 171. | n = 3 hospitals n = 198 breakfasts n = 294 lunches n = 98 dinners | Australia | Collins and Porter [15] |

| Direct weighing. | Direct quantification of the weight of food waste generated by dishes not consumed by patients. Separation by category: organic, recyclable, plastic, and metal. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner. | 1515.2 kg of waste was generated in one day, of which 230 g corresponded to food served and not consumed per day. | Dinner generates the most waste. | n = 1 hospital with 750 beds n = 2010 patient meals | United States | Thiel et al. [31] |

| Direct weighing. | Direct quantification of the weight of food waste generated on plates by patients and waste generated during production. | The average food waste rate from plates was 22.66%. | Total waste was higher during dinners. | n = 366 meals for patients | Canada | McAdams et al. [23] |

| Direct weighing. | Direct quantification of the weight of food waste generated by meals not consumed by patients. | The average food waste generated per plate per patient was 383 g/day. This value includes waste generated at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. | Vegetables were the most discarded item at dinner, followed by milk and yogurt at breakfast. | n = 260 meals from hospitalized patients | New Zealand | Lawrence [32] |

| Visual estimation with structured survey. | Visual observation and categorization of food waste on plates divided into carbohydrates, proteins, vegetables, and fruits. Only lunches were measured. | Waste generated in relation to the portion served consisted of vegetables and proteins (86.7%), followed by carbohydrates (84.8%) and fruits (73.4%). | The highest waste was protein and vegetables at lunch. | n = 246 hospitalized patients | Malaysia | Chemah et al. [24] |

| Mitigation Strategy | Description of the Strategy | Main Results | Population or Sample | Country | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation of a digital ration request system. | Transition from a traditional paper-based system to a digitized and personalized system with options such as on-demand ordering. | Significant reduction in food waste per meal served (from 81 to 33–49 g). Decrease in food waste costs by 32–56%. Estimated annual savings of €38,291 to €77,228. | n = 4362 traditional meals n = 7815 personalized digital meals | The Netherlands | van Bakel et al. [12] |

| Change in the food production system (cook-hold vs. cook-chill). | Comparison between two food preparation and distribution systems: cook-hold (traditional method) and cook-chill (pre-cooked and refrigerated). The aim was to improve the organoleptic quality of the food served. | 85% reduction in food waste when using the cook-hold method. Greater patient satisfaction with cook-hold (97.88%) compared to cook-chill (86.21%). The cook-hold method also resulted in lower energy and diesel consumption. | n = 984 hospitalized patients | Italy | Bux et al. [18] |

| Implementation of a mixed digital mathematical model. | Mixed digital programming models for meal planning, minimizing waste and costs while meeting dietary and nutritional requirements. | Reduction in waste by 22.53% and costs by 32.66%. Projected annual reduction: 5.66 tons of waste and $132,372.24. | n = 1 hospital with a capacity of 1000 beds | United States | Arriz-Jorquiera et al. [25] |

| Integration of more nutritionists into clinical and food services. | Comprehensive nutritional supervision through menu analysis, training, and communication between clinical units and food service. | 25% reduction in total portions wasted; improvement in food safety and patient satisfaction. | n = 18 hospitals (9 with intervention, 9 control) n = 305 meals per day | Israel | Yona et al. [33] |

| Implementation of protocols/audits for quantifying food waste. | Implementation of standardized procedures to measure food waste in hospitals, focusing on waste per serving. | Reduction in waste through temporal analysis. 39% reduction in food waste between 2013 and 2019, from 149 g/patient/meal to 90 g/patient/meal. | n = 17 hospitals | Sweden | Eriksson et al. [29] |

| Modifications in the planning of critical dishes with higher food waste. | Adjustments to recipes and variety of dishes (new chicken recipes and greater variety of fish); reduction in portion sizes. | Significant reduction in waste for chicken (35.7% to 7.2%) and fish (29.5% to 12.8%). | n = 695 trays (second phase of the study) | Spain | Paiva et al. [30] |

| Timely coordination between clinical staff and food services. | Encourage communication and constant updates on changes in patient status (e.g., discharge, diet changes). | Waste related to the delivery of incorrect and extra trays was reduced due to timely real-time communication and direct collaboration between teams. | n = 16 hospitalized patients n = 6 nurses n = 2 hospital directors n = 2 nutritionists n = 2 kitchen staff n = 10 experts in the field | United States | Fuleihan et al. [22] |

| Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles | 3 | 11 | 18 | 15 | 28 | 44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Burgoa Sánchez, C.; de Camargo, A.C. Food Waste in Hospitals: Determining Factors and Sustainable Strategies for Mitigation. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031458

Burgoa Sánchez C, de Camargo AC. Food Waste in Hospitals: Determining Factors and Sustainable Strategies for Mitigation. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031458

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurgoa Sánchez, Camila, and Adriano Costa de Camargo. 2026. "Food Waste in Hospitals: Determining Factors and Sustainable Strategies for Mitigation" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031458

APA StyleBurgoa Sánchez, C., & de Camargo, A. C. (2026). Food Waste in Hospitals: Determining Factors and Sustainable Strategies for Mitigation. Sustainability, 18(3), 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031458