1. Introduction

Inadequate air quality has well-documented adverse impacts on human health and the environment [

1]. Major pollutants such as PM

2.5, PM

10, O

3, CO, NO

2, and SO

2 in urban areas pose significant risks, so accurate prediction and precise short-term forecasting of their concentrations can support early warning and mitigation.

Recent advances in air-quality modelling, prediction and forecasting combine rich observational datasets with powerful machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) methods to improve prediction and forecasting accuracy and interpretability. Most of them highlight a trend towards hybrid, multivariate, and ensemble models that improve prediction accuracy and interpretability.

Table 1 summarises key advanced approaches:

However, in most cases, high-quality pre-processing is very important for these models. All data should be standardised and normalised, missing entries should be removed or imputed (e.g., using linear interpolation or time-series imputation), and outliers and anomalies should be identified and removed. Multicollinearity can be decreased using correlation analysis and methods such as PCA [

12]. Temperature, wind, and humidity, for example, are critical in influencing the dispersion of air pollutants, and their inclusion significantly enhances the accuracy of AI-based models, according to previous research, which emphasises the need for careful integration of meteorological factors [

11]. For instance, ozone (O

3) production is strongly influenced by high temperatures and sunlight [

13], whereas PM may be washed away by precipitation [

14]. Wind speed and direction, as well as rainfall, may also directly affect the precursors of air pollutants. The most pertinent predictors can be found using feature-selection algorithms, such as El Mghouchi’s GEO-based FS [

14]. Building on the framework outlined in [

14], this study aims to deepen understanding of the complex interactions among major air pollutants and various atmospheric and meteorological variables.

The specific objectives are as follows:

Data Pre-processing: Implement robust pre-processing procedures, including advanced imputation methods for short missingness intervals (MICE and KNN), anomaly detection (OCSVM and autoencoders), and frequency-domain denoising (Singular Spectrum Analysis), to ensure high data quality and reliability. The result for this analysis is provided in

Appendix A (

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3 and

Figure A4).

Trend and Temporal Variability Analysis: Investigate the temporal patterns and long-term trends of six key air pollutants—PM2.5, PM10, O3, CO, NO2, and SO2 and the Air Quality Index (AQI). Each pollutant exhibits distinct temporal behaviours influenced by emission sources, atmospheric chemistry, and meteorological dynamics.

Correlation and Relationship Assessment: Examine the interrelations between the six pollutants and meteorological variables through regression and cross-correlation analyses to quantify their mutual dependencies and influence mechanisms.

Causality Analysis: Apply the Granger causality test to identify potential directional relationships between meteorological parameters and pollutant concentrations, determining whether past values of one variable can reliably predict future values of another.

AI-based prediction models: Our approach involved implementing 23 ML and DL algorithms, optimising parameters via Randomised Search CV, Grid Search and Adam Optimizer (

Table A1 and

Table A2 in the

Appendix A). We combined the best-performing model with feature selection strategies to create a high-precision hybrid AI model for air pollutant prediction.

Feature Selection (FS): We employed statistical and machine learning-based feature selection methods to identify the most informative predictors, improving model interpretability and forecasting accuracy while reducing model complexity.

Model Development: We developed and compared multi-step predicting models for the six pollutants using advanced AI algorithms such as XGBoost, Random Forest, CNN, and LSTM to determine the most effective approach for each pollutant.

Hybrid Architecture Exploration: We designed and evaluated hybrid AI frameworks capable of simultaneously capturing temporal dependencies and spatial correlations in pollutant data.

Model Evaluation: We assessed model performance using key statistical metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and mean absolute error (MAE) on unseen test data.

Model Explainability: We applied SHAP value analysis to interpret model predictions, identify dominant features influencing pollutant levels, and strengthen the scientific and policy relevance of the results.

Forecasting Horizon Assessment: We conducted both short-term (one hour) and long-term (several hours ahead) forecasts to evaluate the robustness and generalisation capability of the proposed Deep-NARMAX model under varying temporal scales.

This article is organised as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of the study area and the dataset, detailing the data pre-processing steps, including the identification and treatment of anomalies, outliers, and missing values; and the temporal variability of air pollutants; and describes the AI-Based models; the study framework; and the evaluation criteria adopted by the study.

Section 3 presents and discusses the findings, including the cross-correlation analysis between the six targeted pollutants and the predictors considered; the Granger Causality tests, the Shapley Additive Explanations; the feature selection analysis; the identification of the most effective AI-based models for predicting and forecasting the six air pollutants; and temporal evolution analysis of the Air Quality Index (AQI). Finally,

Section 4 summarises the main conclusions of the study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Sources

This work concentrates on Craiova, the most developed city in southwestern Romania (

Figure 1), using local monitoring data. With sub-Mediterranean influences, Craiova features a transitional temperate continental climate. During summer, temperatures range from 25 °C to 37 °C, with values exceeding 37 °C during heatwaves. Five urban heat islands have been identified in the city centre. The city faces air pollution issues, but it possesses features that could help address this. In general, during winter, the weather is cold, with frost, snow, and occasionally fog. January is recorded as the coldest month of the year (from −8 °C to 3 °C). Cold snaps occur periodically and can bring temperatures below −15 °C.

This study aims to combine air pollutant measurements (e.g., PM, NO

x, CO, VOCs, SO

2, benzene, toluene, xylenes, etc.) with meteorological parameters (solar brightness, temperature, relative humidity, precipitation, wind speed/direction) to forecast pollution levels. Prior Craiova studies have used five-year datasets (2020–2024) comprising around 20 pollution and weather variables from multiple stations [

14]. Built on this dataset, this new approach will help develop deep learning models that integrate atmospheric conditions and pollutant precursors for multi-step forecasting.

The primary data is publicly available and sourced from all four air quality monitoring stations (IDs: DJ1, DJ2, DJ3, and DJ5) in Craiova. They belong to the National Environmental Protection Agency (

https://www.calitateaer.ro/, accessed on 29 April 2025). The data include hourly concentrations of key pollutants—PM

2.5, PM

10, O

3, NO, NO

2, NO

x, CO, SO

2, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, m-/p-/o-xylene—as well as meteorological parameters (solar brightness, temperature, RH, precipitation, wind speed and direction) [

11,

14] (see

Table 2). One example dataset for Craiova consists of approximately 20 variables collected from four monitoring stations over five years [

14]. As a mid-sized industrial city, the air quality in Craiova is affected by local traffic, the centralised heating system, industry, residential complex construction, and weather; for instance, seasonal studies show that ozone accumulation on sunny days is driven by VOC and NO

x precursors and by strong sunlight [

14]. Data pre-processing (e.g., missing value imputation, outlier filtering, and interpolation) will be necessary to clean the multi-year time series. Exploratory analysis (correlation and principal component analysis) will reveal how variables relate; for example, ozone often shows a strong positive correlation with temperature and sunshine and a negative correlation with humidity [

13].

Figure 2 illustrates the temporal distribution of air pollutants and meteorological variables from January 2020 to September 2024, while

Figure 3 shows the percentage of missing values by variables. The dataset includes six target pollutants (O

3, PM

2.5, PM

10, CO, NO

2, and SO

2) along with a set of predictor variables such as nitrogen oxides (NO, NO

x), volatile organic compounds (benzene, ethylbenzene, xylenes, and toluene), and meteorological parameters (precipitation, relative humidity, solar brightness, temperature, wind velocity, and wind direction). Several discontinuities are observed in the time series, indicating periods of missing data, likely due to sensor downtime or data-acquisition interruptions. Despite these gaps, the time series displays consistent temporal and seasonal behaviour, demonstrating the overall reliability of the monitoring network.

To address missing data, the rmmissing function available in MATLAB 2024a was employed. This function automatically removes entries with missing values from an array or table. Specifically, when applied to a vector, it eliminates any element containing missing data; when applied to a matrix or table, it removes any row that includes missing values.

Clear seasonal and interannual patterns are visible across most pollutants. Ozone concentrations exhibit a distinct annual cycle, with higher levels during summer months, reflecting the role of solar radiation and temperature in photochemical ozone formation. In contrast, PM2.5 and PM10 show irregular peaks, typically associated with episodic pollution events such as dust intrusions, traffic-related emissions, or biomass burning. Combustion-related pollutants, including CO and NO2, tend to increase during colder months, reflecting higher fuel consumption and reduced atmospheric dispersion. SO2 concentrations remain generally low, punctuated by occasional spikes that may indicate localised industrial or heating activities.

The synchronous fluctuations of NO and NO2 (NOx) highlight their common origin from vehicular and combustion sources. Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as benzene, xylenes, and toluene exhibit similar episodic increases, often aligning with NOx peaks. This alignment provides strong confirmation of their co-emission from traffic or industrial activities, providing a reliable basis for further research and policy decisions. Conversely, ozone tends to vary inversely with NOx and VOC levels, consistent with the photochemical titration processes that govern ozone dynamics in urban and suburban environments.

Meteorological parameters also display clear periodic behaviours. Relative humidity (RH) and temperature (T) exhibit inverse seasonal trends, with high RH during cooler months and elevated temperatures in summer. Solar brightness follows the expected annual solar cycle and coincides with the observed ozone peaks, emphasising the importance of radiation in ozone formation. Wind velocity and direction show marked short-term variability, reflecting their role in pollutant dispersion and transport. Sporadic precipitation events are associated with temporary decreases in particulate matter concentrations, suggesting wet deposition and atmospheric cleansing effects.

2.2. AI-Based Modelling Framework

The AI-based modelling framework used to analyse the six major air pollutants builds on the foundation established in our previous study [

14]. The methodological approach integrates Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) algorithms explicitly designed for prediction, feature engineering, dimensionality reduction, and time-series forecasting.

For predictive modelling, 23 ML and DL algorithms were implemented, optimised, and compared to determine the most accurate model for each pollutant. The evaluated models include: Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Decision Tree (DT), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Extreme Learning Machine (ELM), Gradient Boosting Machine (GBoost), Extreme Gradient Boosting (xGBoost), Random Forest (RF), Tree Bagger (TreeBag), Generalised Linear Regression (GLR), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Linear Regression (LR), Generalised Additive Model (GAM), Kernelised Ridge Regression (KRR), K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN), Linear Ridge Regression (LRR), Bayesian Linear Regression (BayesLR), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Feedforward Neural Network (FNN), Deep Neural Network (DNN), Residual Neural Network (ResNet), Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and LSTM-based Recurrent Neural Network (LSTM-RNN).

The best-performing model from this prediction stage was further integrated with Feature Selection (FS) and SHAP value analysis to identify the most influential predictors, enhancing model interpretability and forecasting accuracy. As detailed in [

14], 50 feature selection techniques were compared to identify the most effective variable reduction strategies.

In the final stage, future pollutant concentrations were forecasted using advanced statistical and AI-based time-series models. A Deep Nonlinear Autoregressive Moving Average (Deep-NARMAX) model with Exogenous inputs was implemented to capture nonlinear dependencies between pollutants and meteorological variables, providing a robust framework for multi-step air quality forecasting.

To ensure reproducibility, the forecasting setup is defined as follows:

- –

Input Layer: The models utilise a look-back window of past hours of meteorological and pollutant data to capture relationships between them and the target variable. Each target studied here is forecasted alone.

- –

Forecasting Horizon: The study evaluates two horizons: one-step (1 h ahead) and multi-step ahead.

- –

Multi-step Strategy: The Deep-NARMAX model employs a sliding-window approach, using input data at times (t, t − 1, t − 2, …, t − n) to forecast a horizon of (t + 1) hours for single-step forecasting. For multi-step forecasting, the forecast is extended iteratively to (t + 2) hours and beyond. A recursive strategy is adopted for this purpose, whereby the prediction at (t + 1) is fed back as an input to generate the prediction at (t + 2), and so forth.

2.3. Framework and Evaluation Criteria

2.3.1. Study Framework

Below is the operational framework followed in this study:

Data ingestion: Import raw data, timestamp normalisation, flag missing values;

Pre-processing: Remove anomaly and suspect values, gap imputation, outlier handling, resampling;

Exploratory analysis: Analyse trend, distributions, diurnal/seasonal plots, cross-correlation & causality;

Data splitting: Divided data into Train/Test subsets (0.7/0.3) using blocked rolling CV + final chronological holdout;

Prediction Model development: Find candidate models (XGBoost, RF, CNN, LSTM…) → hyperparameter optimisation;

Feature engineering: Find the best predictors for each air pollutant using various FS techniques, permutation importance, and partial dependence;

Evaluation and diagnostics: Compute statistical metrics;

Explainability: Computing SHAP value;

Forecasting Model development: Find the best formula for each pollutant using Deep-NARMAX architecture;

Reporting and deployment: produce standardised plots (diurnal/seasonal, heatmaps, SHAP), store models and scalers, prepare for real-time inference.

2.3.2. Evaluation Criteria and Statistical Indices

In this study, a composite statistical evaluation approach based on a performance score (

φ) was developed and described to assess the effectiveness of various prediction models—Equation (1). This performance score serves as an integrated metric for ranking and comparing regression models, providing a unified framework for quantifying their predictive accuracy and robustness.

where MBE (Mean Bias Error), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), standard deviation σ and TS (Test Statistic) are known as indicators of dispersion (indicators of error), while R

2 (Coefficient of Determination), WIA (Willmott’s Index of Agreement) and SBF (Slope of Best-Fit line) are known as indicators of overall performance. Collectively, these metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of each model’s precision, consistency, and reliability in both prediction and forecasting tasks [

15].

Expressions for these metrics are given below:

where K is the total number of observations;

,

and

are the ith predicted value, ith measured value and mean value, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Temporal Variability of Air Pollutants

Figure 4 presents the diurnal, monthly, and seasonal variations in PM

2.5, PM

10, and O

3 concentrations, together with their hourly distribution profiles. Distinct temporal patterns are evident for each pollutant, reflecting differences in emission sources, atmospheric processes, and meteorological influences.

The diurnal variation in PM2.5 exhibits two pronounced peaks: one during the early morning hours and another at night, with a minimum in the afternoon. Traffic emissions, domestic heating, and limited atmospheric dispersion during stable nocturnal conditions primarily drive this behaviour. The afternoon minimum corresponds to enhanced mixing and dilution due to solar heating and stronger winds. Similarly, PM10 shows a bimodal diurnal pattern, consistent with the accumulation of coarse particles from traffic, resuspension, and local emissions during morning and evening rush hours.

On a monthly and seasonal scale, both PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations are highest during winter and fall and lowest during summer. This seasonal pattern can be attributed to the combined effects of increased combustion sources in colder months, weaker vertical mixing, and frequent temperature inversions that trap pollutants near the surface. Conversely, higher summer temperatures and stronger atmospheric circulation promote particle dispersion and removal, resulting in lower particulate matter levels.

In contrast, ozone (O3) exhibits an inverse temporal behaviour. The diurnal variation shows a typical photochemical pattern, with low concentrations in the early morning and a clear peak in the afternoon (around 14:00–16:00), coinciding with maximum solar radiation and photochemical activity. Ozone levels decrease again in the evening due to titration with nitrogen oxides and reduced photochemical production. On a seasonal basis, ozone reaches its maximum during spring and summer, reflecting enhanced sunlight intensity, higher temperatures, and favourable photochemical conditions for ozone formation, whereas winter values remain significantly lower.

The hourly boxplots further highlight variability in pollutant levels, showing greater dispersion and occasional high outliers at night for PM2.5 and PM10, and in the afternoon for ozone. These outliers represent pollution episodes likely driven by local emission peaks or specific meteorological conditions.

Figure 5 illustrates the diurnal, monthly, and seasonal variations of carbon monoxide (CO), sulphur dioxide (SO

2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO

2) concentrations, along with their hourly distributions. These pollutants are strongly linked to combustion sources such as vehicular traffic, industrial activities, and domestic heating, as reflected in their temporal patterns.

The diurnal variation in CO shows an early-morning minimum, followed by a steady increase throughout the day, peaking in the late evening. This pattern suggests that CO accumulation is influenced by both rush-hour traffic and reduced atmospheric dispersion during nighttime. The monthly and seasonal analyses indicate that CO levels peak in spring, with markedly lower concentrations in summer. Springtime enhancement could be linked to a combination of residual heating emissions, local meteorological stagnation, and potential long-range transport episodes.

For SO2, the diurnal pattern exhibits a pronounced daytime peak around midday, following a nighttime minimum. This increase coincides with the onset of industrial and domestic activities and with vertical mixing of pollutants after sunrise. Monthly, SO2 concentrations remain relatively stable, showing only slight increases during colder months. Seasonally, the pollutant maintains high and nearly constant levels across winter, spring, and fall, which may indicate continuous background emissions from traffic, industrial, or residential combustion sources.

The NO2 time series displays a classic bimodal diurnal structure, characterised by morning and evening peaks, coinciding with peak vehicular traffic, and a distinct midday trough associated with photochemical reactions that convert NO2 into ozone under intense sunlight. Monthly and seasonal trends show elevated NO2 levels in winter and fall, with levels declining in spring and reaching minimum values in summer. These variations result from increased heating and transport emissions, reduced atmospheric mixing in cold months, and enhanced photochemical removal during warm, sunny periods.

The hourly boxplots further emphasise the variability of each pollutant, showing larger ranges and more pronounced outliers during the morning and evening hours for NO2 and CO, while SO2 displays occasional extreme values that may be linked to short-term industrial or emission spikes.

Figure 6 presents the hourly and monthly mean concentrations of the six key pollutants—PM

2.5, PM

10, O

3, CO, NO

2 and SO

2—highlighting their distinct temporal signatures across different months and times of day.

The ozone distribution shows a pronounced daytime maximum, peaking around midday to early afternoon (11:00–16:00), especially during late spring and summer months (May–August). This pattern aligns with enhanced photochemical production under intense solar radiation and higher temperatures. Conversely, nighttime ozone levels remain low due to titration with nitrogen oxides. Both PM2.5 and PM10 exhibit elevated concentrations during winter and early spring, with notable peaks in December–March and reduced levels in summer. Their diurnal cycles are relatively stable but tend to rise during morning and evening hours, reflecting local emission sources (traffic, domestic heating) and limited boundary-layer mixing under colder conditions. CO shows evident seasonal variability, with high concentrations in spring and winter and low levels in summer. Its diurnal profile shows late-evening maxima, consistent with traffic activity and reduced nighttime dispersion. NO2 displays a typical bimodal pattern, characterised by peaks during morning and evening rush hours and minima around midday when photochemical conversion to ozone is strongest. Higher values during winter and fall confirm the strong dependence of NO2 on combustion emissions and atmospheric stability. Finally, SO2 concentrations remain relatively moderate throughout the year but show slight increases during winter and fall, likely associated with domestic heating and lower atmospheric mixing heights. Diurnal variation is modest, with minor increases at midday linked to industrial and traffic-related emissions.

3.2. Cross-Correlation Analysis

Cross-correlation analysis measures the similarity between two time series as a function of their relative displacement. This method assesses the direction and strength of linear correlations between the air pollutants under study and the influencing variables, as well as the time lags at which these relationships are strongest [

16].

Figure 7 illustrates the Pearson correlation coefficients among the pollutants (PM

2.5, PM

10, O

3, CO, NO

2, SO

2) and the set of meteorological and gaseous predictor variables. Several notable patterns emerge, revealing both direct and inverse dependencies that highlight the interplay between primary emissions, secondary formation, and meteorological influence. The ozone (O

3) concentration shows strong negative correlations with NO

2 (r = −0.62), NO

x (r = −0.56), and CO (r = −0.45), indicating that high levels of primary pollutants coincide with reduced ozone due to titration reactions and limited photochemical production. This inverse relationship is consistent with the NO titration effect observed in high-traffic urban environments, where fresh nitric oxide (NO) emissions scavenge ozone (NO + O

3 → NO

2 + O

2), particularly during periods of low solar radiation or high vehicle activity. Conversely, ozone is positively correlated with solar brightness (r = 0.52) and temperature (r = 0.49), confirming the role of photochemical activity under intense solar radiation and warm conditions. Particulate matter (PM

2.5 and PM

10) exhibits a strong mutual correlation (r = 0.81), confirming their shared sources and atmospheric behaviour. Both pollutants correlate highly with CO (r = 0.80 and 0.61), NO

2 (r = 0.59 and 0.55), suggesting that they originate from traffic and combustion emissions. Additionally, PM

2.5 exhibits a robust correlation with benzene (r = 0.82) and other aromatic hydrocarbons, suggesting that fine particulate pollution is linked to volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions. The relationship between CO and NO

2 is also strong (r = 0.65), consistent with their common vehicular source. Meanwhile, SO

2 shows only weak to moderate correlations with most pollutants (maximum r = 0.24 with NO

2), implying distinct or more sporadic emission sources, such as industrial and domestic fuel combustion. Meteorological variables show expected influences: relative humidity (RH) is inversely correlated with ozone (r = −0.48) and temperature (r = −0.67), whereas solar brightness is positively associated with temperature (r = 0.42) and inversely with PM

2.5 and PM

10. These relationships highlight how meteorological conditions regulate pollutant dispersion and secondary formation processes.

3.3. Granger Causality Tests

A statistical hypothesis test called Granger causality is used to determine if one time series can accurately predict another [

17]. To determine whether historical values of meteorological and other air variables can significantly predict future pollution, and vice versa, this study will employ Granger causality tests. This test helps identify directional relationships between variables, providing insights into potential causal influences.

Figure 8 and

Table 3 present the results of the Granger causality test among the pollutants studied and their predictor variables, expressed as F-statistic and

p-value heatmaps. This analysis identifies potential directional (causal) influences between pollutants and influencing factors, revealing both short-term and lagged interdependencies that go beyond simple correlation.

The F-statistic heatmap (top panel) highlights several statistically significant causal relationships. Among the pollutants, NO2 appears to exert a strong causal effect on ozone (F = 73.58, p < 0.001), reflecting the well-known photochemical titration effect, in which NO2 and NO participate in ozone formation and depletion cycles. Similarly, NO2 has significant effects on CO (F = 44.87) and PM2.5 (F = 34.75), suggesting that vehicular and combustion emissions contribute simultaneously to both particulate and gaseous pollutants.

Meteorological variables also show significant causal effects on pollutant levels. Solar brightness and temperature strongly influence ozone (F = 113.55 and 65.88, both with p < 0.001), underscoring the role of photochemical activity and thermal enhancement in ozone formation. Conversely, relative humidity (RH) exerts a negative causal influence on ozone (F = 55.37, p < 0.001), suggesting that it reduces photochemical efficiency by increasing cloud cover and moisture.

The p-value heatmap (bottom panel) confirms these relationships, indicating that most causal links between pollutants and meteorological variables are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (p < 0.05). Notably, insignificant relationships (p > 0.05) are observed between ozone and precipitation, or between ozone and toluene, indicating weaker short-term dynamic links with these variables.

Overall, the Granger causality analysis reveals that ozone dynamics are primarily governed by NO2, solar brightness, and temperature, while NO2-related traffic emissions mainly influence PM and CO concentrations. These findings reinforce the conclusion that photochemical and combustion processes jointly drive the temporal evolution of air pollutants, validating their inclusion as predictors in subsequent modelling and forecasting frameworks.

3.4. Temporal Evolution of the Air Quality Index (AQI)

In this subsection, air quality is analysed using the computed Air Quality Index (AQI) for the six major pollutants. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines, the overall air quality level is determined by the maximum AQI value among pollutants, which serves as a representative indicator of the general air quality.

While this approach is widely adopted, it inherently overlooks pollutant-specific health impacts. We argue that air quality should ideally be assessed individually for each pollutant, as the dominant pollutant may not always reflect the cumulative or differential exposure risks. This perspective might be further explored in future studies.

In the present work, however, we adhere to the WHO-recommended methodology by first computing the AQI for each pollutant and then identifying the maximum index value to categorise air quality into the standard classes: Good, Moderate, Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups, Unhealthy, Very Unhealthy, and Hazardous. The detailed classification thresholds and pollutant-specific requirements are summarised in

Table 4.

The upper panel (

Figure 9) illustrates the evolution of the total AQI, the maximum AQI among the six pollutants, from January 2020 to September 2024, highlighting the dominant pollutant at each point in time. Overall, the AQI fluctuates within low to moderate levels for most of the study period, suggesting generally acceptable air quality with occasional pollution peaks. A notable spike is observed during mid-2022, where AQI values exceeded 1000, primarily driven by CO, indicating an episode of severe air pollution likely associated with either a local emission event (e.g., combustion, traffic congestion, or industrial release) or meteorological stagnation. Periods dominated by SO

2 and PM

10 are recurrent, especially during winter and spring, when atmospheric conditions typically favour pollutant accumulation.

The lower-left panel presents the frequency of dominance among the six major pollutants. The analysis reveals that SO2 overwhelmingly dominates the AQI contribution, accounting for the highest frequency of exceedances, followed by PM10 and NO2. This pattern suggests that industrial emissions and vehicular exhaust remain the primary drivers of air quality degradation in the region. The lower frequencies of CO, O3, and PM2.5 indicate that these pollutants, while important, play a secondary role in determining daily AQI dominance.

The pie chart on the lower right quantifies the relative contributions of the primary pollutants to the total AQI. SO2 is the leading contributor, accounting for more than half of the total AQI burden. PM10 and NO2 follow with moderate shares, reflecting the combined effects of vehicular traffic, industrial activities, and resuspended dust. In contrast, CO and PM2.5 contribute minimally, and O3 plays a relatively minor role during the analysed period. This distribution indicates that primary pollutants—particularly those directly emitted from combustion sources—dominate over secondary pollutants such as ozone.

Collectively,

Figure 9 underscores that the air quality in the study area is primarily influenced by SO

2, PM

10, and NO

2, with occasional severe pollution episodes linked to CO spikes. The dominance of these pollutants underscores the need for targeted emission control strategies focused on fuel quality, industrial desulphurisation, and particulate matter abatement. Moreover, the observed temporal variations highlight the influence of seasonal meteorology and anthropogenic activities on pollutant dynamics.

3.5. Best AI-Based Predicting Models

Table 5 summarises the statistical performance of the best-performing AI-based models for each pollutant during training and testing. The results demonstrate the high predictive accuracy and generalisation capability of the selected models across all pollutants, albeit with varying degrees of robustness.

For PM2.5 and PM10, the XGBoost model achieved outstanding performance during training (R2 = 0.99 and 0.99, respectively) and maintained high accuracy during testing (R2 = 0.90 for PM2.5; R2 = 0.79 for PM10). Despite slight performance degradation during testing, the results confirm the model’s strong ability to capture particulate dynamics driven by complex nonlinear interactions among VOCs and meteorological variables.

Ozone (O3) and sulphur dioxide (SO2) were best predicted by Random Forest models, achieving R2 = 0.96 and 0.87 during training, and 0.89 and 0.41 during testing, respectively. The relatively lower testing correlation for SO2 reflects its more episodic and source-dependent nature, which can limit model generalisation.

Carbon monoxide (CO) prediction using XGBoost yielded R2 = 0.95 on training and 0.64 in testing, suggesting that CO variability is influenced by highly transient emission patterns, such as traffic intensity.

Finally, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), modelled using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), showed exceptional predictive stability with R2 values above 0.99 for both phases and minimal errors (RMSE < 0.7 µg/m3), highlighting the CNN’s capability to learn spatiotemporal features effectively.

Overall, these findings confirm that ensemble-based (XGBoost, Random Forest) and deep learning (CNN) architectures outperform conventional models, demonstrating their suitability for nonlinear air quality prediction tasks and providing a robust foundation for further deployment in real-time forecasting systems.

Table 6 summarises performance comparison with recent multivariate air pollution prediction studies between 2020 and 2025.

3.6. Shapley Additive Explanations

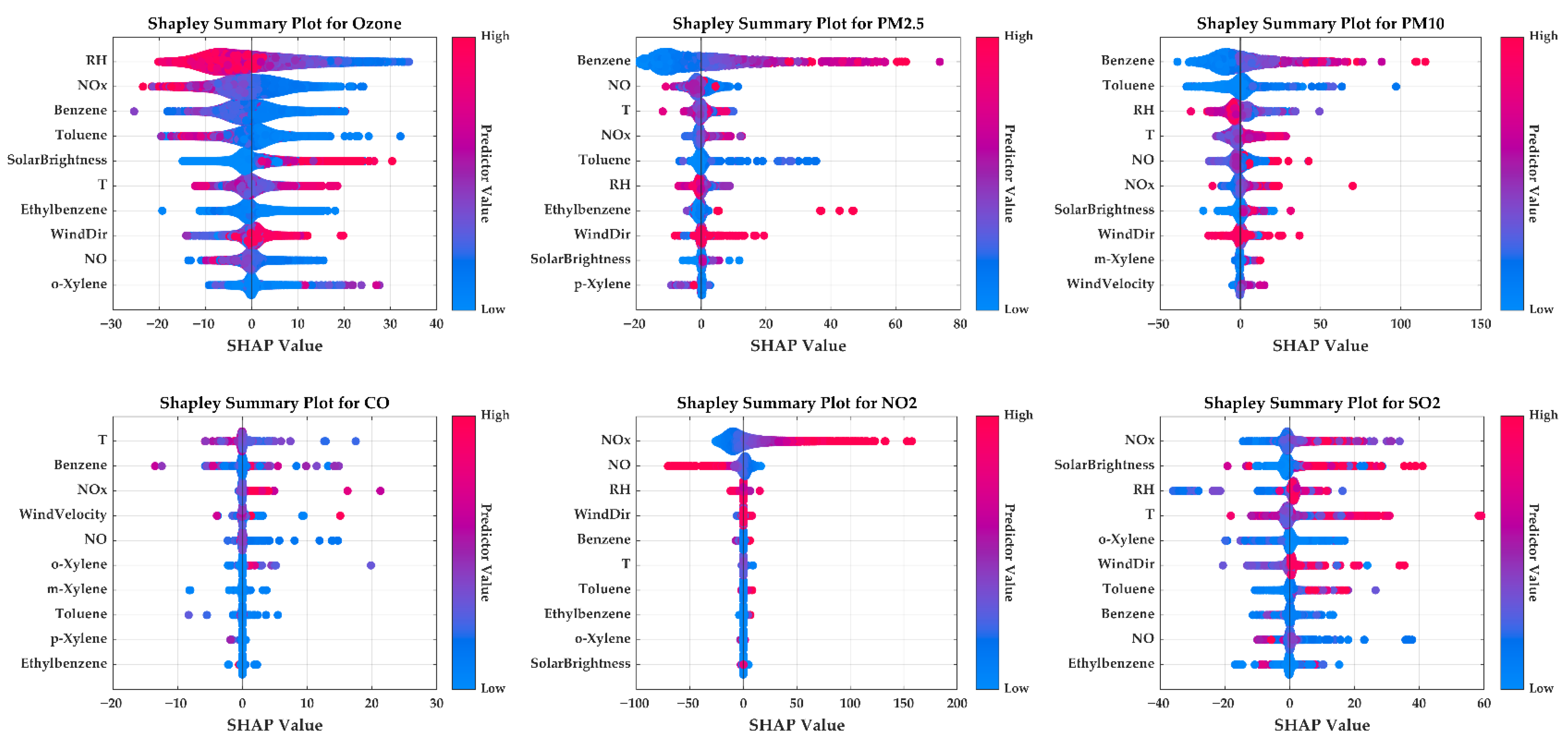

Figure 10 illustrates the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) results for the six pollutants, highlighting the most influential meteorological and chemical predictors affecting their concentrations. For ozone (O

3), relative humidity (RH), NO

x, solar brightness, and temperature are the dominant variables. High RH and NO

x exhibit negative SHAP values, indicating ozone suppression under humid or NO-rich conditions, whereas intense solar radiation and elevated temperatures enhance photochemical ozone formation.

For PM2.5 and PM10, benzene, toluene, NO2 and NO are the main predictors, reflecting the role of combustion-related VOCs and nitrogen oxides in secondary particle formation. High VOC levels contribute positively to particulate accumulation, while humidity has a moderate positive effect, especially on PM10, due to hygroscopic growth. In the case of carbon monoxide (CO), temperature, benzene, and NOx exert the most significant influence, indicating a strong link between CO levels and vehicular emissions. For nitrogen dioxide (NO2), NO dominates, reflecting direct chemical coupling, whereas RH reduces NO2 through wet deposition. For sulphur dioxide (SO2), the most influential variables are NOx, solar brightness, RH, and temperature: dry, sunny conditions enhance concentrations, whereas high humidity promotes SO2 removal.

Overall, SHAP results confirm that NOx, VOCs (benzene, toluene, xylenes), and key meteorological factors (RH, temperature, solar brightness) consistently drive pollutant behaviour, underscoring the intertwined effects of emission sources and atmospheric processes on air quality dynamics.

3.7. Feature Selection

Figure 11 summarises the best features selected by each of the fifty-feature section (FS) methods.

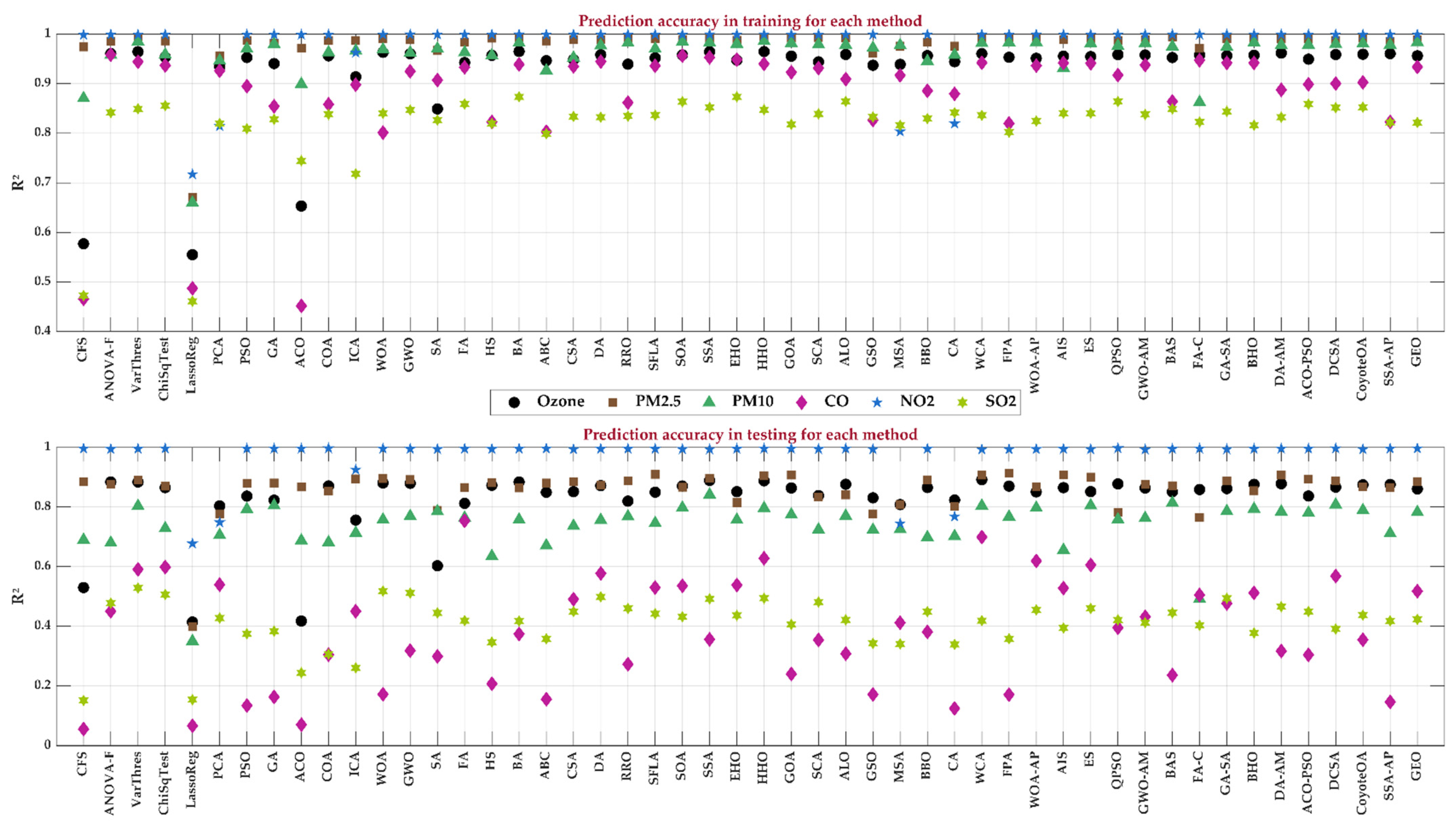

Figure 12 presents a comprehensive statistical comparison of the prediction accuracy achieved by the hybrid AI-based FS framework across all evaluated methods for the six pollutants. This is performed for both training and testing stages.

The figure displays the R2 values for both training and testing phases, allowing a clear assessment of the robustness, generalisation, and stability of each FS technique when coupled with the predicting model. The results highlight substantial variability in predictive performance across methods, confirming that FS directly and significantly influences model prediction accuracy.

During the training phase, most FS techniques yield strong predictive behaviour for O3, PM2.5, PM10, CO, and NO2, with R2 values generally exceeding 0.85. This result indicates that the hybrid AI–FS architecture successfully captures the intrinsic structure and nonlinear relationships within the high-dimensional dataset. Some traditional methods, such as CFS, ANOVA-F, Chi-square Test, and LassoReg, show moderate performance, while most bio-inspired and swarm-intelligence-based optimisers—such as PSO, GA, GWO, HHO, and SSA—achieve consistently higher R2 values, often approaching or exceeding 0.95 for specific pollutants. The elevated clustering of points near the top of the training plot reflects the ability of these optimisers to search the feature space and efficiently identify informative subsets.

In contrast, the testing phase (bottom panel) reveals greater variability across methods, providing more insight into their generalisation capability and susceptibility to overfitting. While pollutants such as O3, PM2.5, and NO2 maintain high predictive quality—with many methods sustaining R2 values above 0.80—the performance for CO, PM10, and especially SO2 shows more dispersed patterns. This behaviour highlights the increased difficulty of modelling pollutants with irregular emissions or episodic fluctuations. Notably, some FS techniques that perform well during training (e.g., ACO, BA, and CSA) show a clear drop in testing accuracy, suggesting potential overfitting. Conversely, methods such as PSO, GA, GWO-AM, and several adaptive or hybrid metaheuristics demonstrate superior stability, preserving high R2 values during testing across pollutants.

A recurring trend is the comparatively lower accuracy for SO2 across nearly all FS methods, with many testing R2 values falling between 0.20 and 0.50. This finding aligns with the pollutant-specific results from the prediction analysis. It reinforces the notion that SO2 exhibits highly irregular, source-dependent behaviour that is less predictable through data-driven approaches alone. On the other hand, the consistently high performance for NO2, with many FS techniques achieving R2 ≈ 1 during both training and testing, illustrates a strong and stable relationship between NO2 variability and the selected explanatory variables.

Table 7 summarises the statistical analysis of the best hybrid AI-based FS model across all FS methods studied for predicting each of the six pollutants.

3.8. Deep-NARMAX Models

Table 8 summarises the best-performing Deep-NARMAX models for forecasting the concentrations of the six pollutants included in this study, along with the statistical analysis and the model formulas, highlighting the most commonly employed features.

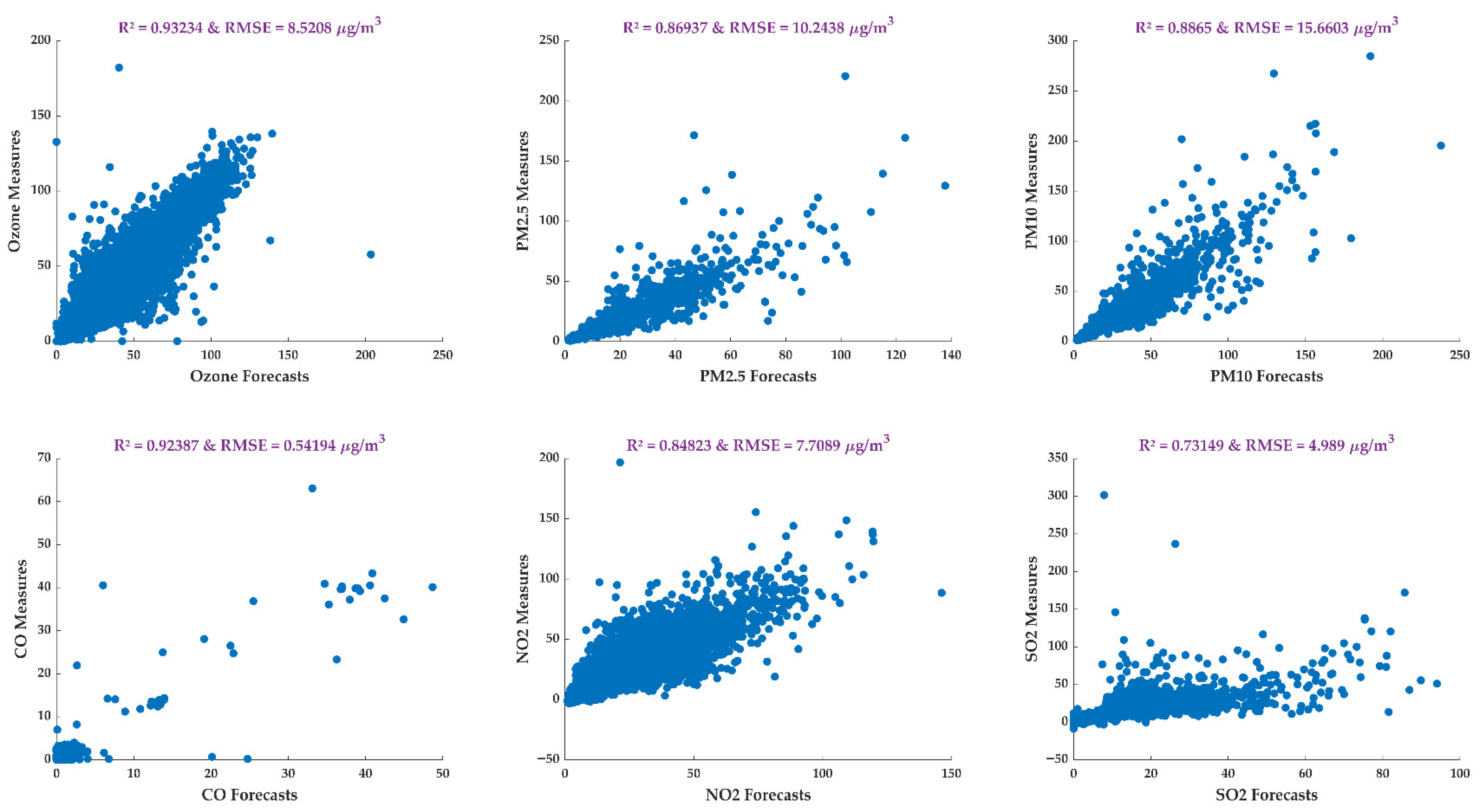

Figure 13 illustrates the corresponding scatter plots. Each subplot compares the observed and predicted values and reports the corresponding R

2 and RMSE metrics.

For ozone, the Deep-NARMAX model achieves the highest predictive accuracy among all pollutants, with an R2 of 0.93. The figure shows a tight alignment between observed and forecast values, especially in the moderate concentration range, indicating that the model effectively learns the photochemical processes driving ozone formation. Deviations are most pronounced at high concentrations, where nonlinear atmospheric chemistry and meteorological interactions become more complex. Even so, forecast performance remains excellent.

The models for PM2.5 and PM10 also show strong predictive capability, achieving R2 values of 0.87 and 0.89, respectively. Both scatter plots show a clear linear trend, though a wider spread is observed at higher concentrations. PM10 shows slightly greater dispersion than PM2.5, which can be attributed to coarse particles generated by dust events and mechanical processes, which are more challenging to model deterministically. Nevertheless, the results confirm that Deep-NARMAX can reliably reproduce temporal fluctuations in particulate pollutants.

For CO, the model achieves R2 = 0.92, with a compact cluster of points near the identity line. The model demonstrates high accuracy in capturing both baseline and peak concentrations. In contrast, the results for NO2 show a moderate increase in dispersion, particularly at concentrations above 100 µg/m3. With R2 = 0.85, the Deep-NARMAX model still performs well, but the increased scatter reflects the complexity of the coupled NO–NO2–O3 chemical system. Rapid titration effects and dependence on solar radiation introduce significant variability, challenging short-term forecasting models.

Among the six pollutants, SO2 is the most difficult, yielding the lowest performance (R2 = 0.73). The scatter plot displays higher vertical dispersion, indicating both underestimation and overestimation across a broad concentration range. This reduced accuracy is consistent with the episodic nature of SO2 emissions, typically driven by industrial combustion sources and abrupt short-lived events, which are harder for data-driven models to learn from limited historical patterns. Despite this, the model still reasonably well captures the general temporal behaviour of SO2.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive, fully integrated AI-driven framework for understanding, predicting, and forecasting the complex dynamics of air pollution from multivariate environmental and atmospheric data. By combining correlation analysis, Granger causality, feature selection, model interpretability, and deep nonlinear forecasting models, the framework ensures both statistical robustness and physical transparency in interpreting pollutant behaviour.

The results highlight the effectiveness of advanced machine learning and deep learning techniques in capturing the nonlinear interactions between pollutants and meteorological variables. Ensemble learning models such as XGBoost and Random Forest, as well as deep neural architectures such as CNNs, consistently outperformed traditional methods on prediction tasks. Feature selection experiments—spanning fifty techniques—showed that metaheuristic and swarm-intelligence-based optimisers provide the most accurate and stable predictor subsets. These methods yielded higher and more reliable R2 scores for O3, PM2.5, PM10, NO2, and CO, whereas SO2 proved the most challenging to model due to its episodic and source-dependent nature.

SHAP-based interpretability analysis confirmed the dominant role of meteorological conditions, especially relative humidity, temperature, wind patterns, and solar radiation, in shaping pollutant concentrations. The NO2–NO–O3 photochemical triad also emerged as a central driver of ozone dynamics, while SO2 and PM10 were frequently identified as the main contributors to deteriorating air quality. These insights bridge the gap between data-driven modelling and atmospheric science by linking model behaviour to known chemical and physical processes.

Forecasting experiments using the Deep-NARMAX framework demonstrated a strong alignment between predicted and observed concentrations, with R2 values ranging from 0.73 to 0.93 and low dispersion indicators across pollutants. Ozone, PM2.5, PM10, and NO2 showed particularly robust forecast performance, confirming the suitability of nonlinear dynamic models for short-term air quality forecasting. Although the forecasting accuracy for CO and SO2 was comparatively lower, the results remain satisfactory given the inherent irregularity and noise in these pollutants.

The Air Quality Index (AQI) assessment provided additional insights into temporal patterns of air quality under WHO and EPA guidelines. While current AQI standards rely solely on the maximum pollutant sub-index, our findings suggest that pollutant-specific AQI assessments offer a more informative and nuanced understanding of exposure risks. This approach highlights the importance of revisiting multi-pollutant AQI formulations in future research.

In summary, the proposed hybrid AI framework shows high predictive accuracy, interpretability, and generalisability, providing a powerful tool for real-time air quality prediction and forecasting, as well as for evidence-based environmental policy planning. Future work will focus on expanding the framework to spatiotemporal modelling using real-time sensor networks, incorporating uncertainty quantification, and developing improved multi-pollutant AQI metrics that more accurately reflect actual health risks.