1. Introduction

Orange production is among the world’s most important fruit-based cropping systems due to its economic, social, and nutritional relevance; similarly, at the national level, citriculture constitutes a significant sector of the economy [

1]. In recent years, vegetation indices derived from multispectral and satellite imagery, particularly the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), have transformed precision agriculture by enabling dynamic and spatially explicit assessments of plant health and vigor [

2,

3]. NDVI has been widely validated as a proxy for chlorophyll content and green biomass, providing an effective decision-support tool for agronomic management [

3]. However, most studies have focused on periods of active vegetative growth and fruit development, while the immediate post-harvest interval—a critical phase during which plants must replenish reserves and repair tissues—has received comparatively less attention [

4].

In parallel, agricultural biostimulants have gained increasing interest due to their potential to enhance plant resilience and optimize physiological processes. Organic products formulated from fishery and livestock/agro-industrial residues have been associated with improved enzymatic activity, chlorophyll synthesis, and photosynthetic efficiency. Nevertheless, evidence linking biostimulant application to the temporal behavior of vegetation indices during post-harvest recovery remains limited. For citrus crops in particular, studies integrating NDVI measurements before and after harvest together with biostimulant applications are still scarce [

4,

5]. This knowledge gap constrains the development of agronomic strategies aimed at accelerating canopy vigor recovery after harvest and supporting more sustainable production cycles.

Within this context, the present study addresses the need for scientific evidence on the relationship between the application of a biostimulant derived from fishery and agro-livestock residues and NDVI variability as an indirect indicator of plant vigor, providing pre- and post-harvest assessments in orange orchards to support more efficient and sustainable post-harvest management.

In the district of La Yarada Los Palos, located in the Tacna region of southern Peru, citrus production—particularly orange cultivation—faces constraints that undermine competitiveness and long-term sustainability. Despite a 265.84% increase in cultivated land between 2000 and 2020 [

6], local growers continue to experience limitations in managing post-harvest stress, which compromises fruit quality and shelf life and reduces market value, regardless of other structural challenges such as limited water availability [

7].

Post-harvest stress in citrus is manifested through loss of turgor, changes in firmness and peel color, and increased susceptibility to disease. In La Yarada Los Palos, extreme climatic conditions, especially high temperatures and low relative humidity, intensified by climate change, exacerbate these effects [

8], while water scarcity and aquifer overexploitation further restrict post-harvest recovery [

9].

A persistent limitation is the low availability and adoption of advanced technologies for monitoring post-harvest stress. Although multispectral remote sensing and UAV platforms offer effective tools for early detection of canopy stress [

10], their local implementation remains constrained by economic barriers and insufficient technical training [

11]. In parallel, biostimulants derived from fish proteins and agricultural residues have shown potential to enhance post-harvest recovery by stimulating key physiological processes [

12,

13], yet evidence of their application in citrus orchards in La Yarada Los Palos remains scarce [

14].

Overall, the central local problem is the lack of integrated technological tools for managing post-harvest stress in citrus production. Combining remote monitoring approaches with biostimulant-based management represents a key opportunity to improve fruit quality and strengthen the sustainability of agricultural production in the region.

In the La Yarada Los Palos district (Tacna, Peru), physiological crop monitoring systems such as drone-based multispectral remote sensing have not yet been formally implemented. Current practices rely mainly on pressurized irrigation and occasional soil testing, while NDVI-based assessments of post-harvest vegetative vigor in citrus orchards are not routinely applied. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI), Tacna is characterized by a desert climate with high solar radiation, temperatures between 12 and 30 °C, very low annual rainfall (~200 mm), and saline-affected soils, underscoring the need for monitoring canopy recovery after harvest [

15].

At the national level, the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (MINAGRI) and the National Institute for Agricultural Innovation (INIA) have promoted the use of UAVs and multispectral sensors in horticultural crops such as tomato and potato, consolidating NDVI-based approaches for estimating water and nutritional stress [

16]. However, these initiatives have largely focused on active production stages and annual crops, without addressing post-harvest dynamics in perennial fruit systems such as orange, resulting in methodological gaps.

Internationally, organic biostimulants derived from animal sources have been associated with enhanced photosynthesis, improved nutrient uptake, and increased tolerance to abiotic stress [

17]. Nevertheless, evidence integrating biostimulant applications with NDVI monitoring in citrus remains limited, revealing both a technological gap related to local implementation of remote sensing and a methodological gap linked to the validation of biostimulant effects using objective indicators.

This study addresses these gaps by integrating multispectral remote sensing with an organic biostimulant adapted to the agroclimatic conditions of Tacna, contributing to the development of a precision agriculture framework for perennial fruit crops in arid environments.

Orange is one of the most important fruit crops worldwide, nationally, and locally. Brazil and the United States are among the leading global producers, while in Peru, orange cultivation is particularly relevant in regions such as Junín and Tacna, where cultivars such as Valencia and Navel are widely grown. Orange production plays a key role in food security and economic stability, generating employment throughout the entire value chain [

1,

15,

18]. In Peru, post-harvest quality is critical to maintaining competitiveness and ensuring that fruit reaches consumers with acceptable nutritional and sensory attributes. However, significant post-harvest losses have been reported, mainly associated with mechanical damage, microbial contamination, and inadequate handling during transport and storage [

8,

18,

19].

To mitigate these losses, Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs), including those recommended by SENASA, have been implemented to improve post-harvest management from harvest to storage and distribution, supporting product quality and compliance with international export standards [

20]. Despite these efforts, post-harvest stress remains a major challenge in citrus production, driven by dehydration, unsuitable temperatures, and oxidative stress, leading to firmness loss, reduced quality, and increased susceptibility to disease [

8]. Water loss after harvest further exacerbates pulp softening and quality deterioration, particularly under low relative humidity [

19], and when post-harvest handling is inadequate, losses may be substantial [

8,

18].

Biostimulants are natural substances that enhance plant growth, productivity, and tolerance to abiotic stress by stimulating metabolic processes rather than directly supplying nutrients. Their application has been associated with improved nutrient-use efficiency, enhanced water retention, and increased resilience to drought, salinity, and temperature extremes [

5,

12,

17]. Biostimulants derived from fishery and agro-livestock residues, typically obtained through enzymatic hydrolysis, contain bioactive compounds such as amino acids, peptides, and minerals that can promote root development, chlorophyll synthesis, and water conservation, thereby supporting plant performance under water-limited conditions [

17,

21,

22,

23]. Their use may also reduce dependence on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, contributing to more sustainable agricultural practices [

24].

Within this context, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) has become a cornerstone indicator for assessing plant physiological status. Computed from red (R) and near-infrared (NIR) spectral bands, the NDVI reflects chlorophyll absorption and vegetation structure, with higher values indicating dense, healthy canopies and lower values reflecting stressed or sparse vegetation. The NDVI is strongly associated with photosynthetic activity and has proven effective for detecting stress related to drought, pests, and nutrient deficiencies, often before visual symptoms appear [

2,

3]. Its integration with complementary monitoring technologies such as thermography and spectroscopy has further improved crop diagnostics and sustainability outcomes in resource-limited regions [

25,

26].

Multispectral monitoring supported by UAV and satellite platforms enables detailed, non-invasive assessment of crop status with high spatial and temporal resolution, supporting timely decision-making and improved yield forecasting while reducing the environmental footprint of agricultural activities [

2,

27,

28,

29]. When integrated with geographic information systems (GISs) and artificial intelligence, NDVI-based analyses enhance the early detection of nutrient deficiencies, pest pressure, and plant diseases, strengthening farmers’ capacity to respond to emerging constraints [

28,

30].

Today, PA is widely recognized as a key approach for addressing global challenges including climate change, water scarcity, and the need to increase agricultural productivity in a sustainable manner [

31,

32,

33]. The incorporation of emerging technologies has strengthened data-driven decision-making, allowing the optimization of water, nutrient, and input management while reducing environmental impacts and improving crop performance, particularly through precision irrigation and water-saving strategies under changing climatic conditions [

32,

33].

The agricultural sector faces increasing pressure to adopt sustainable practices that safeguard productivity while reducing reliance on synthetic inputs. In this context, organic biostimulants have emerged as effective tools for enhancing plant metabolism, post-harvest vigor, and climate resilience [

30,

34,

35]. In particular, the reuse of fishery and agro-livestock residues to produce bioinputs aligns with circular economy principles and waste reduction strategies supported by public policies and international sustainability frameworks [

36].

In citrus crops such as orange (Citrus sinensis), post-harvest vigor monitoring is critical because it directly influences canopy development and yield potential in the subsequent growing season [

37,

38]. The NDVI is a widely adopted, non-destructive, and cost-effective indicator of plant physiological status, applicable across multiple spatial scales using satellite sensors, UAV platforms, or ground-based systems [

39,

40].

Accordingly, this study is justified by the need to generate scientific evidence integrating remote sensing-based monitoring tools with agroecological practices to support more efficient, sustainable, and adaptable citrus production systems. Specifically, the study quantifies post-harvest canopy recovery in a commercial ‘Washington Navel’ orange orchard under hyper-arid coastal conditions using UAV-derived NDVI products and evaluates the contribution of an on-farm, residue-based organic biostimulant by comparing treated and control plots across three UAV flights within a randomized complete block design.

Despite the growing use of UAV-based vegetation indices in citrus orchards, most existing studies have focused on active growth stages, yield estimation, or long-term canopy development, with limited attention to the immediate post-harvest period, a phenological phase characterized by physiological stress and canopy recovery dynamics. In particular, the quantitative characterization of post-harvest canopy recovery using the NDVI, especially under hyper-arid conditions and in response to organic biostimulant applications, remains largely unexplored. This knowledge gap is agronomically and environmentally significant, as post-harvest stress can strongly influence subsequent canopy vigor, orchard resilience, and resource-use efficiency in water-limited citrus production systems.

Previous UAV-based studies in citrus orchards have primarily employed vegetation indices such as the NDVI to support canopy vigor characterization, disease detection, and yield estimation during active growth phases [

25,

28,

41,

42,

43,

44]. For example, the UAV-derived NDVI has been used to describe canopy structure and vigor related to productivity metrics [

42,

44], and multispectral UAV imagery has been applied to detect citrus greening disease and spectral differences between healthy and stressed trees [

28,

41,

43]. Although these studies demonstrate the utility of UAV-based vegetation indices for orchard monitoring, they remain largely focused on productive or vegetative stages. In contrast, the present study advances current UAV applications by targeting the immediate post-harvest period. Moreover, by integrating UAV-derived NDVI monitoring with the evaluation of an on-farm, residue-based organic biostimulant, this work extends the use of UAV tools from diagnostic monitoring toward the assessment of adaptive, sustainability-oriented management practices under hyper-arid conditions.

From a sustainability perspective, this research contributes to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 (Zero Hunger) by supporting resilient citrus production systems, to SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) through the valorization of locally available agricultural and fishery residues within a circular economy framework, and to SDG 13 (Climate Action) by promoting adaptive, data-driven agricultural practices in regions increasingly affected by climate variability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Experimental Orchard

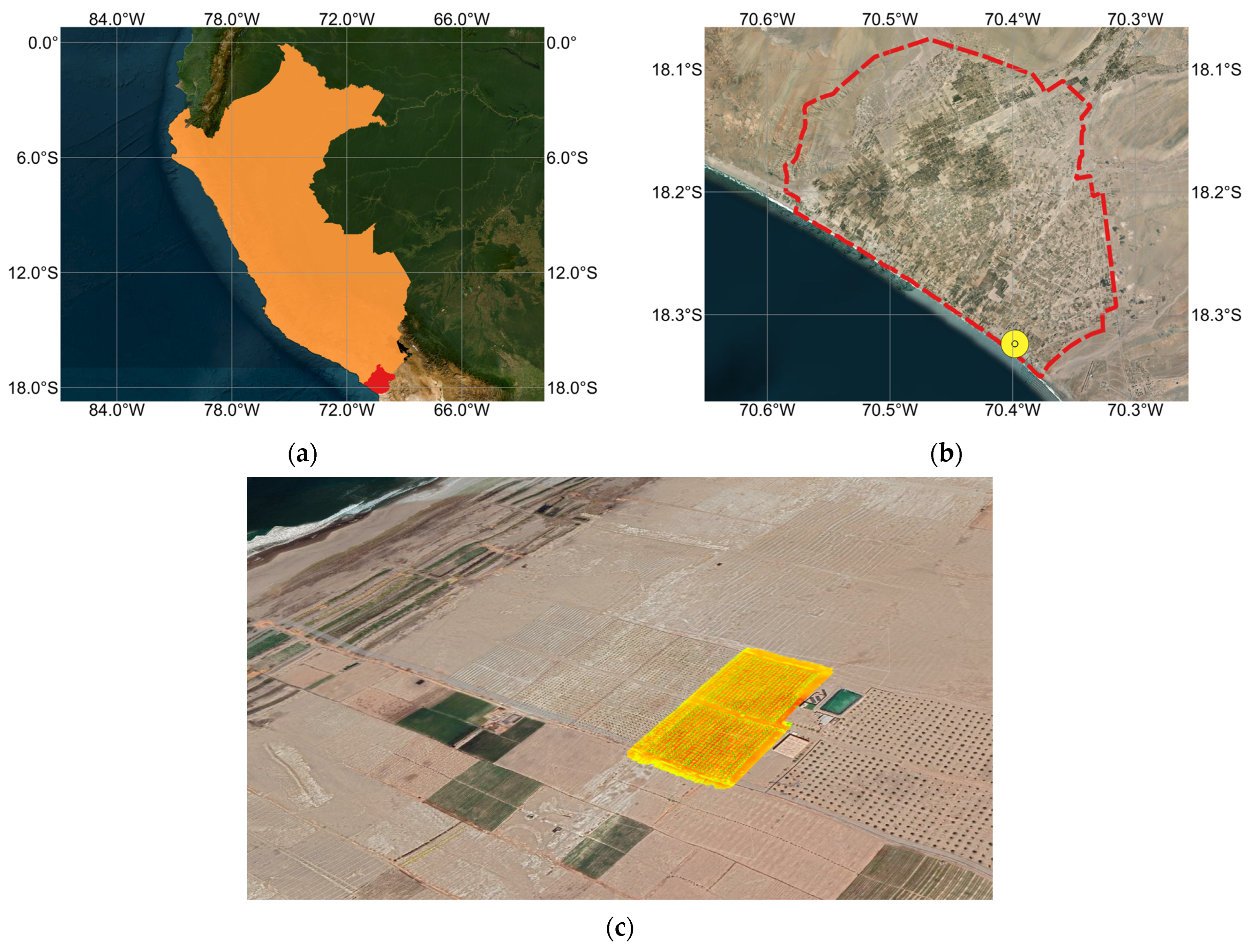

This study was carried out in the La Yarada Los Palos district, Tacna Region, in the southern coastal plain of Peru near the border with Chile (

Figure 1). This area forms part of a hyper-arid coastal desert where annual rainfall is very low and most precipitation occurs as occasional winter drizzle rather than effective rain [

45]. Crop production depends almost entirely on groundwater extracted from the coastal aquifer, conveyed through pressurized irrigation systems [

46]. High evaporative demand, intense solar radiation, and persistent winds, together with the presence of shallow groundwater of variable salinity, make irrigated agriculture particularly sensitive to both water-quality and irrigation-management decisions [

6,

9,

47].

La Yarada Los Palos is characterized by intensively managed irrigated agriculture established on predominantly alluvial and colluvial soils. The landscape is occupied by a mosaic of perennial and annual crops, including olives, citrus, grapevine and other fruit trees, as well as vegetables and forage species. These systems are typically organized in medium- to small-scale farms that rely on drip or sprinkler irrigation and combine soil fertilization with fertigation to sustain yields under water-limited conditions. Sweet orange has become one of the flagship crops in the district, reflecting both the favorable climatic conditions for citrus cultivation and strong local and regional demand for fresh fruit. Orange orchards in the area are commonly managed via high-frequency drip irrigation, with careful nutrient management implemented to maintain canopy vigor and fruit quality despite the underlying constraints of aridity and groundwater salinity.

Within this broader agricultural setting, the present experiment focused on a commercial orange orchard representative of the local production systems and water-management constraints present in La Yarada Los Palos. The orchard is supplied exclusively by groundwater and managed using standard commercial practices, making it a suitable case study for evaluating whether an on-farm, residue-based biostimulant can measurably enhance canopy vigor under real-world conditions. The flat topography and regular planting pattern also provide favorable conditions for performing UAV-based monitoring of canopy status using vegetation indices such as the NDVI.

2.2. Experimental Design and Treatments

This study was established in a commercial ‘Washington Navel’ sweet orange orchard (local “Huando”-type) managed via drip irrigation. The trees were five years old at the start of the monitoring period and planted with 4 m × 4.5 m spacing, corresponding to a density of 555 trees ha−1 (18 m2 per tree). Within a relatively homogeneous block of the orchard, sixteen multi-tree plots were delineated for UAV-based monitoring and treatment comparison. Each plot consisted of a fixed group of neighboring trees within the same planting geometry, with no missing trees or severe canopy damage, to minimize edge effects and small-scale variability in canopy structure.

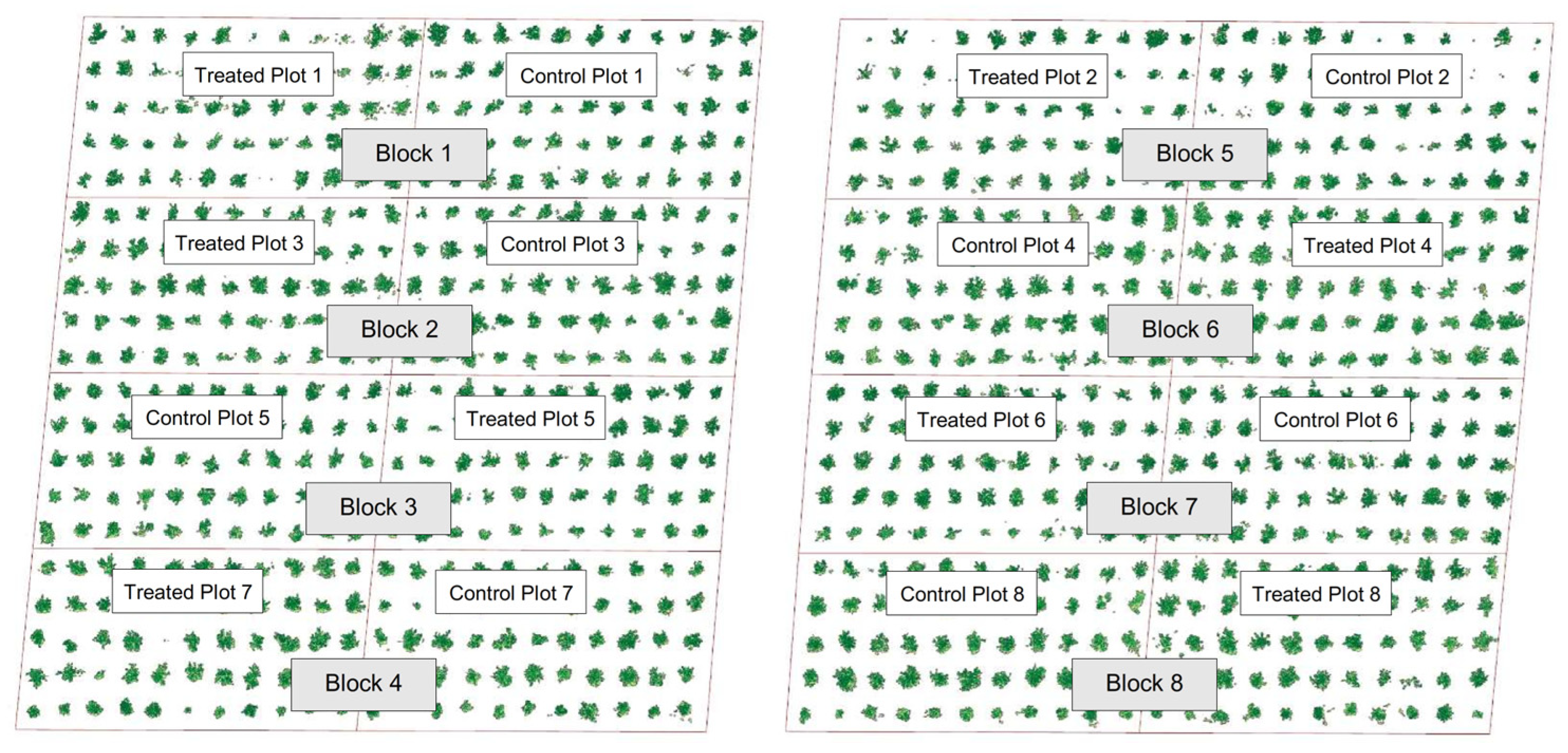

The experiment followed a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with eight spatial blocks (

Figure 2). Each block comprised two adjacent multi-tree plots with comparable canopy condition, with one plot assigned to the biostimulant and the other serving as an untreated control. The treatment allocation within each block was randomized using a random-number generator to reduce potential bias from local field gradients [

15,

48].

The sixteen plots were assigned to two treatments: eight control plots and eight plots receiving a residue-based biostimulant. Plot assignment was carried out within the selected block to ensure that tree age, planting pattern, and baseline management was as similar as possible between treatments. All plots were subjected to the same agronomic management approach, including drip irrigation with groundwater, basal soil fertilization with potassium sulfate (500 g tree−1) and diammonium phosphate (DAP, 100 g tree−1), fertigation with ammonium nitrate and calcium nitrate during fruit growth and soluble potassium sulfate during fruit filling, and foliar applications of a commercial micronutrient blend containing Zn, Fe, and Mn (1 L ha−1) at the pre-flowering and post-fruit set stages. Weed control, pest management, and any pruning followed the grower’s routine practices and were kept identical across treatments. The only deliberate difference between the control and treated plots was the application of an on-farm, residue-based biostimulant.

Canopy status was monitored via UAV on three key dates. Flight 1 (29 April 2025) and Flight 2 (29 June 2025) were conducted before any application of the residue-based biostimulant and jointly represent the pre-treatment period. Between Flight 2 and Flight 3, the biostimulant was applied only to the eight treated plots through a short series of fertigation events, while the eight control plots did not receive any biostimulant. Four applications were carried out on 1, 8, 15 and 22 August 2025, and Flight 3 (29 August 2025) was conducted as a post-treatment flight, ensuring that we had a consistent set of two pre-treatment and one post-treatment observations for each of the sixteen plots.

The commercial harvest took place on 24 July 2025, so Flight 3 captured canopy status during the early post-harvest recovery period.

2.3. Residue-Based Biostimulant and Application Protocol

The treated plots received an on-farm, residue-based organic biostimulant prepared from locally available waste streams generated within the production unit and its immediate surroundings. The formulation combined orchard plant residues (spoiled/over-ripe fruit culls, dried leaves and leaf litter, chopped pruning material, and chopped leguminous foliage), animal manures (cattle, hen, and rabbit manures), and locally sourced organic and mineral inputs (fish processing residues from the nearby coastal zone, milk surplus, cane molasses, wood ash, and agricultural lime) [

23,

49]. This mixture was co-developed by the research team and the orchard manager as a low-cost, circular economy strategy to recycle nutrients and organic matter into a liquid amendment with potential biostimulant effects on citrus canopies rather than as a standardized commercial product. The ingredient composition and nominal amounts used in the study batch are reported in

Table 1.

All components were mixed with water in a cylindrical plastic tank (total capacity: 3500 L) installed within the orchard. The tank was mounted on a simple wooden structure to facilitate manual stirring and safe access and equipped with a bottom valve connected directly to the drip irrigation system. During the preparation period, the mixture was periodically homogenized to promote the decomposition and solubilization of organic components [

16,

23,

49,

50]. Field operators used basic personal protective equipment (laboratory coat, gloves, helmet, and mask) during handling and stirring. A single batch of approximately 3500 L was produced via a consistent on-farm protocol, and water was added as needed to reach the target final volume.

Application was carried out exclusively in the eight treated plots via fertigation through the existing pressurized drip irrigation system, ensuring the delivery of the biostimulant to the root zone at the base of each tree. The outlet valve of the 3500 L tank was connected to the drip lines to provide uniform distribution and a controlled dose per tree. Four applications were performed between Flight 2 and Flight 3 (1, 8, 15, and 22 August 2025), each delivering approximately 1 L/tree−1 (cumulative dose: ~4 L/tree−1). The timing and duration of these fertigation events were identical across treated plots, and no biostimulant was applied to the control plots. All other aspects of irrigation, fertilization, and pest and weed management were kept comparable between treatments, so that differences in the canopy NDVI and high-vigor canopy fraction could be attributed to the residue-based biostimulant rather than to changes in baseline agronomic practices.

It should be noted that the residue-based organic biostimulant formulation described in this study is context-specific and reflects the availability of organic residues within the study area. Rather than constituting a fixed or universal recipe, the selected inputs represent functional categories based on their primary roles within the formulation, including organic nitrogen sources, carbon-rich substrates supporting microbial activity, amino acid- and protein-rich residues, structural plant biomass, and mineral buffering inputs. These functional categories and their corresponding roles are summarized in

Table 2, together with examples of locally adaptable materials.

Accordingly, the methodological approach is designed to be adaptable, allowing functionally equivalent residue streams available in other production contexts to be substituted, provided that comparable functional roles are preserved and basic operational conditions (e.g., adequate mixing, avoidance of anaerobic blockage, and delivery through fertigation-compatible systems) are respected. Replicability is therefore grounded in maintaining these functional characteristics and in applying a consistent preparation and application process (aqueous co-mixing, periodic homogenization, and fertigation-based delivery), rather than in reproducing exact ingredient types or quantities. This framework supports contextual reproducibility across different agroecosystems, while acknowledging that future efforts aimed at defining minimum compositional criteria, processing guidelines, and quality control benchmarks would further enhance standardization and inter-site comparability.

2.4. UAV Platform, Sensors and Flight Planning

Canopy monitoring was carried out via a DJI Mavic 3 Multispectral (M3M; DJI, Shenzhen, China), a rotary-wing UAV integrating an RGB camera and a multispectral sensor array. The multispectral module acquires narrowband imagery in the green, red, red-edge and near-infrared (NIR) regions of the spectrum, enabling the computation of standard vegetation indices such as the NDVI from the red and NIR bands. The platform also includes an integrated GNSS receiver with RTK capability that records the position of each image and supports georeferenced orthomosaic generation at plot scale.

Three UAV flights were conducted over the experimental orange orchard during the 2025 growing season on 29 April (Flight 1), 29 June (Flight 2) and 29 August (Flight 3). All missions were flown under stable weather conditions at around solar noon and with clear or only slightly cloudy skies, minimizing cast shadows and directional illumination effects on the canopy reflectance. For each date, a single flight was planned to cover the orchard and a small surrounding buffer in a regular “lawn-mower” pattern.

All flights were carried out at a nominal altitude of 15 m above ground level. To ensure complete coverage of the experimental area and high-quality orthomosaics, the flight plans specified 80% forward overlap and 70% side overlap between successive images. These parameters are critical for producing geometrically accurate and radiometrically consistent orthomosaics and for reducing noise in the derived reflectance products. Under these conditions, the average spatial resolution of the multispectral imagery was approximately 0.67 cm pixel−1, which is sufficient to resolve fine-scale variability in the vigor of individual Citrus sinensis canopies.

Flight plans were created in the manufacturer’s mission-planning software (DJI Pilot 2 v2.5.1), using the same altitude, overlap, and camera orientation across the three dates to ensure comparable ground sampling distance and viewing geometry. The high forward and side overlap between images, together with the onboard GNSS geotagging of each exposure, provided the basis for accurate georeferencing and radiometrically consistent orthomosaics. Subsequent photogrammetric processing and NDVI map generation are described in

Section 2.5.

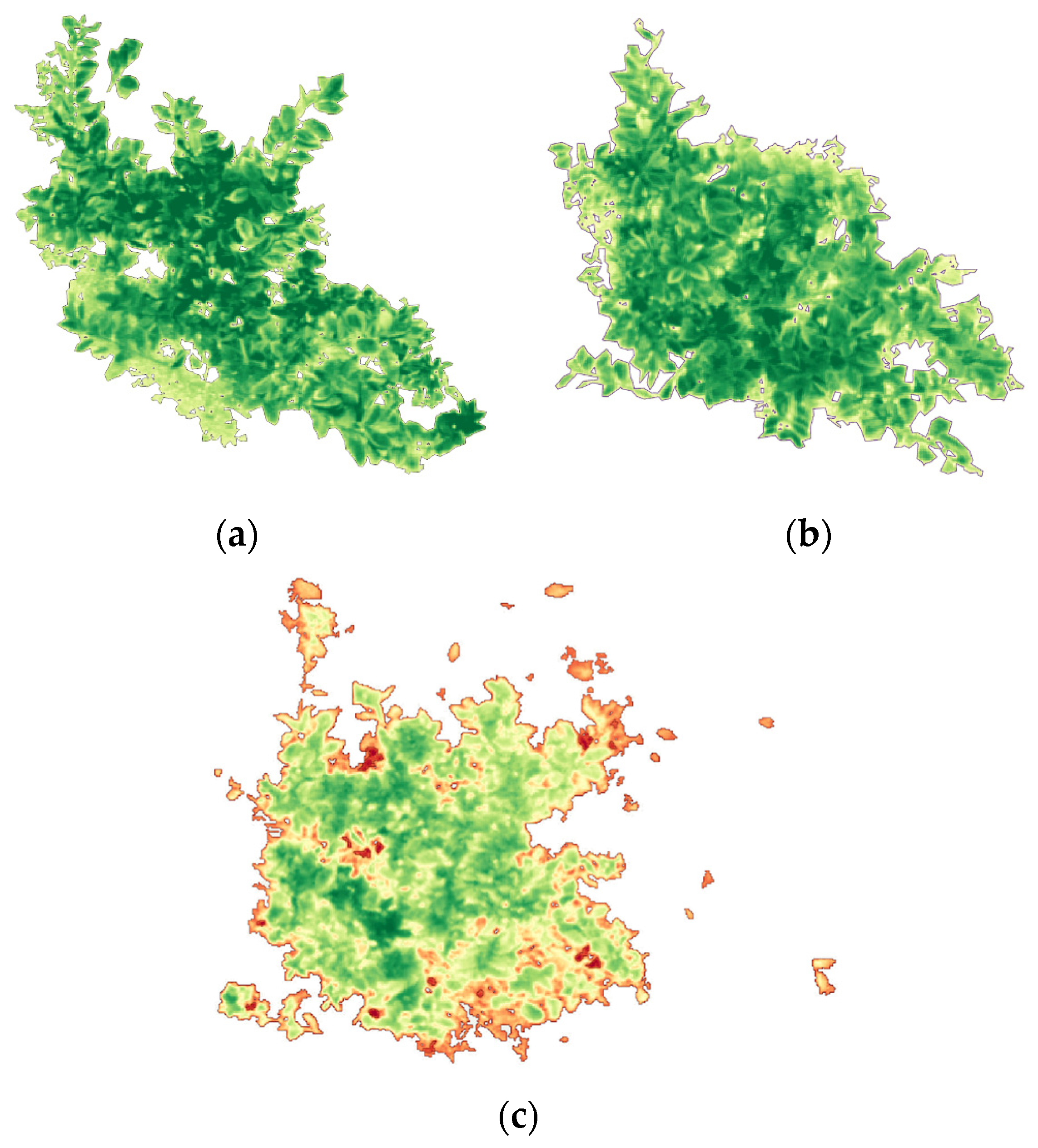

2.5. Image Processing and NDVI Computation

Multispectral images from each UAV flight were processed via Agisoft Metashape Professional, v2.2.3 using the standard multispectral workflow. For each date, all raw images from the Mavic 3 Multispectral were imported, grouped by flight, and aligned using the GNSS image positions recorded onboard. Georeferenced orthomosaics were then generated separately for each flight, using identical processing parameters across dates to ensure comparability. The final multispectral orthomosaics were exported at a native ground resolution of approximately 0.67 cm pixel−1 in a UTM coordinate system referenced to WGS 84.

The exported orthomosaics were subsequently handled using ArcGIS Pro 3.5.0. For each flight, the red and near-infrared (NIR) bands were used to compute the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) on a per-pixel basis according to

where NIR represents the reflectance value in the near-infrared band and Red represents the reflectance value in the red band, both extracted from the multispectral orthomosaics on a per-pixel basis. NDVI values theoretically range from −1 to +1, with higher positive values indicating denser and healthier vegetation.

NDVI rasters were clipped to the extent of the experimental orchard and checked visually to identify and remove obvious artifacts near image borders or in non-vegetated areas not relevant to this study. All NDVI products from the three flights were kept at the same spatial resolution and projection, providing a consistent basis for the subsequent extraction of plot-level canopy metrics described in

Section 2.6.

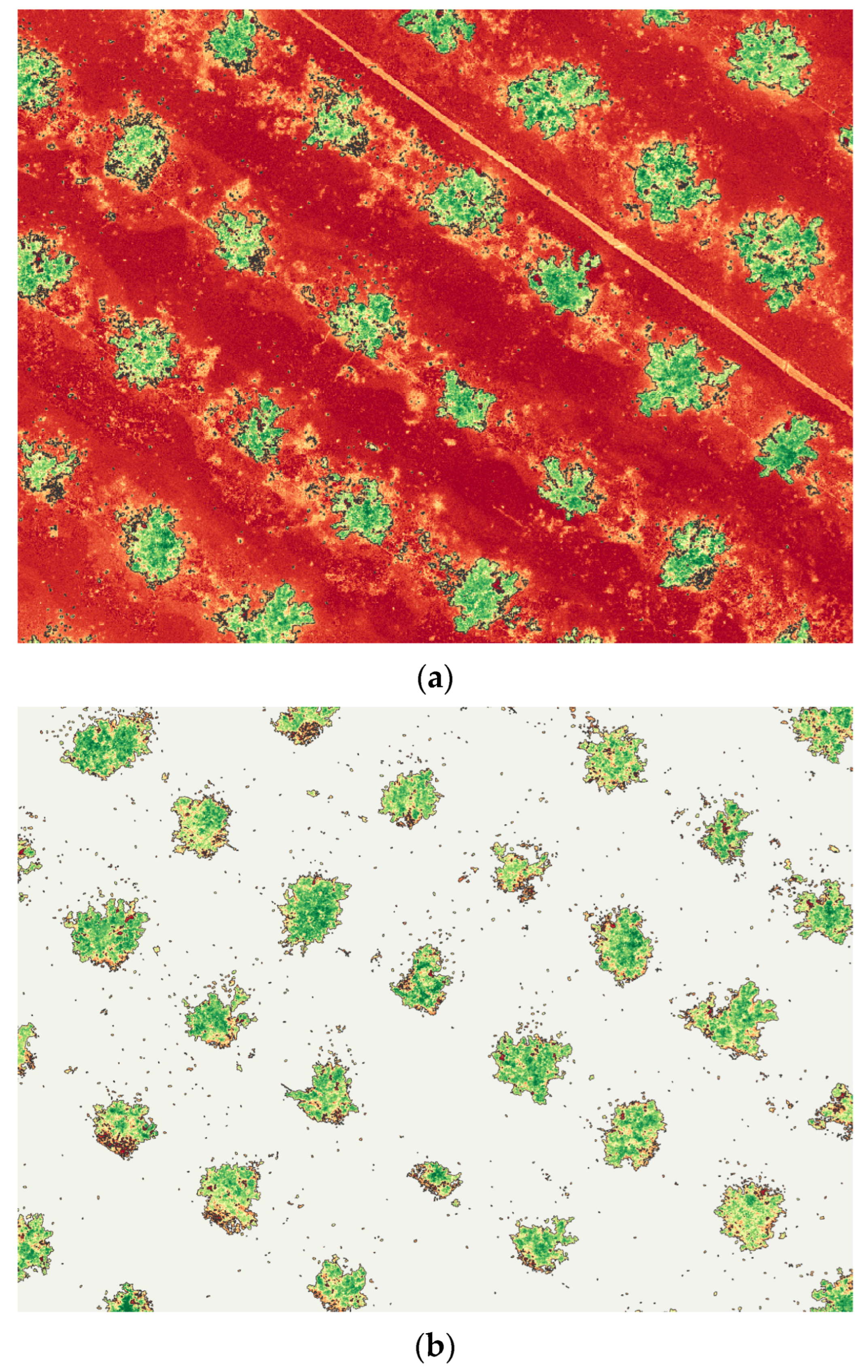

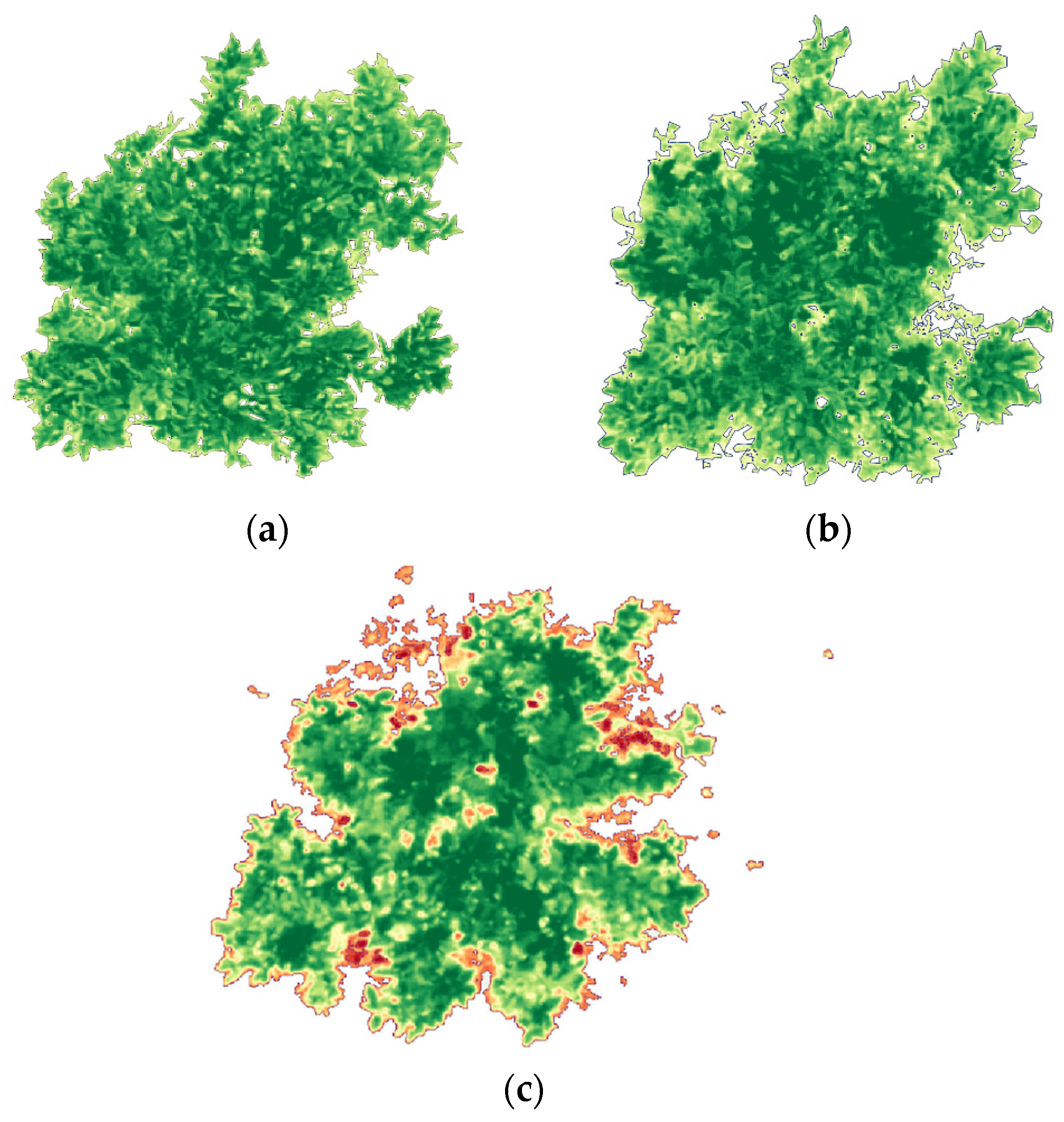

A canopy mask was applied to isolate citrus crowns and exclude non-canopy pixels (bare soil, inter-row areas, access tracks, and mixed edge pixels) that can bias NDVI values and inflate within-plot variability (

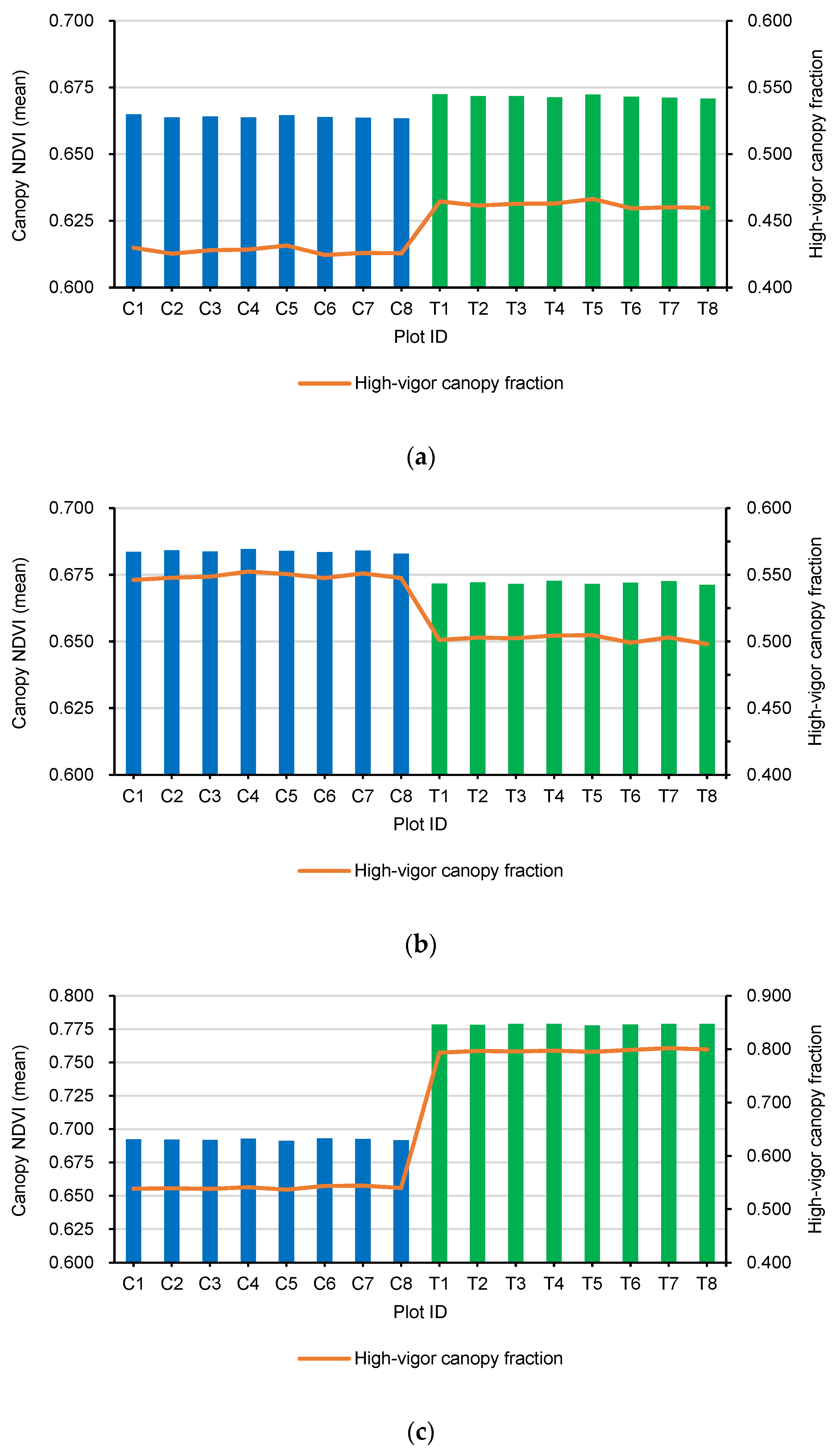

Figure 3). This step is particularly important in orchards with discontinuous canopy cover, where soil background and shadow effects can dominate the signal if the full scene is analyzed. By restricting calculations to canopy-only pixels using the same masking approach across flights, we ensured that plot-level NDVI metrics reflected the true canopy conditions and remained comparable over time.

The UAV-based analysis was intentionally focused on the NDVI as a robust, widely validated indicator of canopy greenness, structural integrity, and overall vigor, suitable for capturing spatial and temporal patterns of post-harvest canopy recovery at orchard scale. The study objective was not to resolve specific physiological or hydric mechanisms at the leaf or plant level, but rather to quantify treatment-related differences in canopy recovery dynamics following harvest under operational field conditions. Consequently, additional indices associated with chlorophyll concentration or plant water status (e.g., EVI, GNDVI, NDMI, MSI) were not included in the present analysis. While such indices can provide valuable insights into underlying physiological processes, their integration requires dedicated experimental designs and ancillary measurements beyond the scope of this study.

2.6. Plot Delineation and Canopy Masking

The sixteen experimental plots (eight control plots, and eight treated plots) were arranged in the orchard following a block layout (blocks B1–B8; see

Section 2.2). This field layout was first digitized as a vector map using ArcGIS Pro, drawing one polygon for each plot based on the orchard map and the UAV orthomosaics and ensuring that plot boundaries followed the tree rows while excluding border trees that could be influenced by adjacent management. The same set of 16 polygons was then used to clip the NDVI rasters from Flights 1, 2, and 3 so that identical ground areas were analyzed on all dates.

To isolate only the citrus canopy within each plot, an NDVI-based mask was applied. Visual inspection of the multispectral orthomosaics and NDVI histograms showed that bare soil, shadows, and inter-row spaces consistently exhibited low NDVI values, whereas Citrus sinensis canopies had clearly higher NDVI values [

31,

51]. On this basis, a minimum NDVI threshold was defined and applied uniformly across all flights to retain only pixels dominated by live canopy and to exclude soil and non-vegetated areas. The resulting binary canopy mask was intersected with the plot polygons, yielding for each flight and plot a cloud of NDVI pixels representing only the tree canopy.

These per-plot canopy pixel sets formed the basis for computing the plot-level canopy NDVI statistics and high-vigor canopy fractions described in

Section 2.7.

2.7. Canopy Metrics: Mean NDVI and High-Vigor Canopy Fraction

For each flight, the NDVI orthomosaics were intersected with the plot polygons and the canopy mask described in

Section 2.6, yielding a cloud of canopy pixels for every plot (8 control and 8 treated plots per date) [

30,

32]. Within each plot, the canopy NDVI (mean) was defined as the arithmetic mean of the NDVI across all canopy pixels:

where

n is the total number of canopy pixels within the plot after masking, and NDVI

i is the NDVI value of the

i-th canopy pixel [

52].

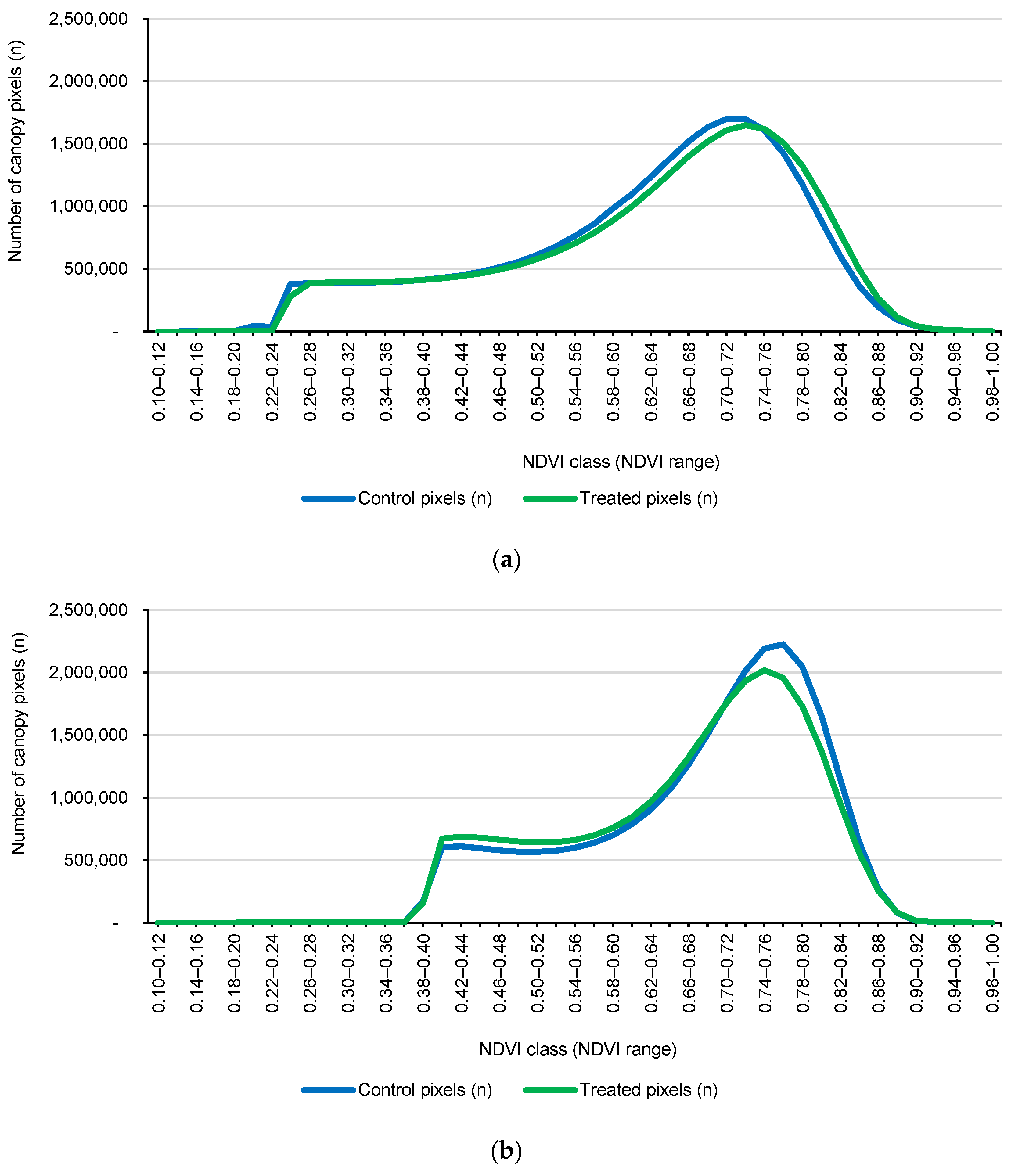

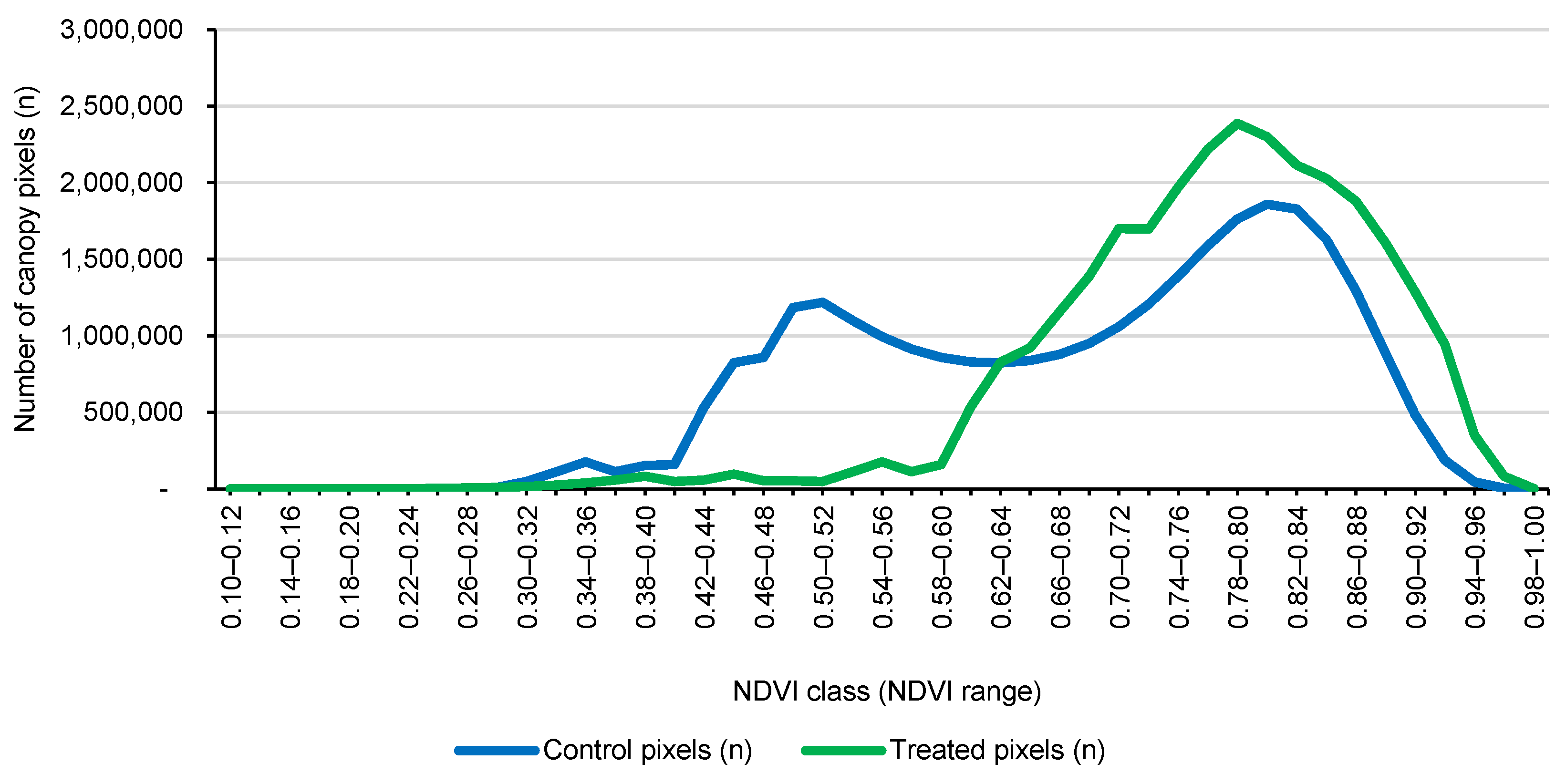

To quantify the proportion of highly vigorous foliage, we defined a high-vigor canopy fraction based on a fixed NDVI threshold. Visual inspection of NDVI histograms for the orange canopy and prior experience with citrus orchards in the study area indicated that NDVI values above approximately 0.70 correspond to the densest, healthiest canopy. We therefore classified all canopy pixels with an NDVI ≥ 0.70 as “high-vigor”. For each plot and flight, the high-vigor canopy fraction was computed as

where

nNDVI ≥ 0.70 is the number of canopy pixels with NDVI values equal to or greater than the threshold of 0.70, and

ncanopy is the total number of canopy pixels within the plot.

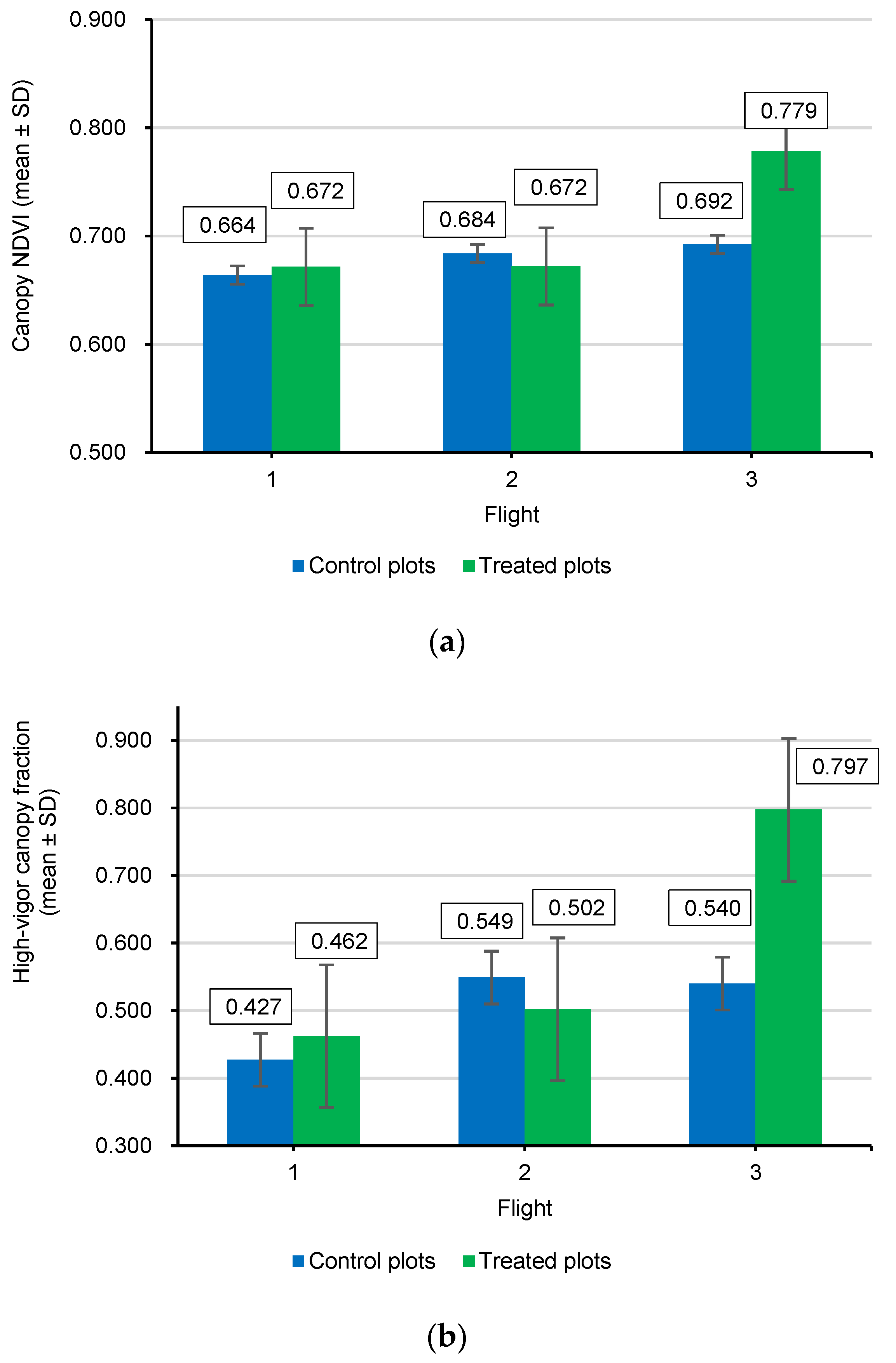

Both metrics (canopy NDVI mean and high-vigor canopy fraction) were calculated independently for each of the 16 plots and for each of the 3 flights. These plot-level values were then summarized by treatment (control vs. biostimulant-treated) and flight as mean ± standard deviation and subsequently used to derive the pre- and post-treatment contrasts described in

Section 2.8.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The experimental unit for all analyses was the plot (

n = 8 control and

n = 8 biostimulant-treated plots). For each flight and treatment, the plot-level values of canopy NDVI (mean) and high-vigor canopy fraction were first computed as described in

Section 2.7 and then summarized across plots as mean ± standard deviation (SD). These flight- and treatment-specific means form the basis for all contrasts.

Let

ȲT,f and

ȲC,f denote the mean response (canopy NDVI or high-vigor fraction) for the treated and control plots, respectively, at flight

f (

f = 1, 2, 3). For each flight, the instantaneous treatment contrast was defined as

The pre-treatment contrast was calculated as the average of Flights 1 and 2:

whereas the post-treatment contrast corresponded to Flight 3,

The net biostimulant effect in absolute units was then

For each flight, the percentage difference between treated and control was computed relative to the control mean as

The pre- and post-treatment percentage contrasts were obtained as

and the net percentage effect was

where

ȲT,f and

ȲC,f are the mean plot-level responses of the treated and control plots at flight

f, respectively; Δ

f represents the treatment contrast for flight

f; Δ

pre is the average contrast across the two pre-application flights (Flights 1 and 2); and Δ

post corresponds to the post-application contrast (Flight 3). Percentage contrasts represent relative differences between treated and control plots normalized by the control mean.

To formally test whether the biostimulant produced a detectable canopy response after application, two-sided, two-sample t-tests were performed for comparing control and treated plots in Flight 3 for each response variable. The significance level was set at α = 0.05. All analyses were performed in R (R Core Team).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of a residue-based organic biostimulant in enhancing citrus canopy vigor, particularly during the early post-harvest recovery period. Using a high-resolution UAV-based NDVI, combined with a robust experimental design, allowed us to capture meaningful treatment effects and observe the impact of biostimulant application on canopy vigor, leaf health, and canopy structure over time.

4.1. Biostimulant Effects on Canopy Vigor and Recovery

The data presented here highlight that trees receiving the residue-based biostimulant exhibited significantly higher canopy vigor compared to control trees. While control plots showed a noticeable decline in vigor following harvest (as expected during the post-harvest recovery phase), the trees in the treated plots maintained a stronger canopy response, as indicated by the higher NDVI values and greater high-vigor canopy fraction observed during Flight 3. This response is particularly important because post-harvest stress often leads to reduced tree health, with potential implications for fruit quality and overall productivity [

20,

54]. By the end of the monitoring period (Flight 3), treated trees exhibited a marked shift in the NDVI towards higher values (approximately +12.5%), translating to healthier foliage and a greater proportion of the canopy being classified as high vigor (an increase of +47.6%).

The observed increase in canopy vigor in the treated plots is temporally associated with the application of the residue-based organic biostimulant, which is composed of organic residues including fish-processing wastes, agro-industrial by-products, and plant-based residues. These components are known to contain nutrients, amino acids, and bioactive compounds that can support plant metabolic activity and recovery following stress. Consistent with previous studies reporting positive effects of biostimulants on plant resilience to abiotic stresses such as nutrient limitation and drought [

13,

16], treated trees in this study showed a faster and more pronounced recovery signal compared to untreated controls.

The magnitude and direction of the canopy vigor response observed in this study are consistent with previous UAV-based investigations in citrus orchards that reported NDVI as a sensitive indicator of canopy condition and stress status during active growth phases. For example, Chang et al. demonstrated that the UAV-derived NDVI effectively discriminates between healthy and stressed citrus canopies, showing systematic reductions in NDVI associated with physiological impairment and disease presence [

28]. Similarly, Bakas et al. reported strong associations between NDVI-based canopy metrics and citrus tree productivity and structural vigor, confirming the suitability of the NDVI for plot-level canopy assessment using high-resolution UAV imagery [

43].

However, most previous UAV-based citrus studies have focused on yield estimation, disease detection, or canopy characterization during productive or vegetative growth stages [

28,

30,

43,

44], whereas quantitative analyses of the immediate post-harvest recovery period remain scarce. In this context, the relative increases observed in the present study—approximately +12.5% in the mean canopy NDVI and +47.6% in the high-vigor canopy fraction following biostimulant application—are notable, as they fall within or exceed the range of NDVI contrasts qualitatively reported between stressed and non-stressed citrus canopies under field conditions [

28,

44].

From a biostimulant perspective, the observed response aligns with experimental evidence showing that protein hydrolysates and residue-derived biostimulants can enhance photosynthetic performance, nutrient-use efficiency, and stress tolerance in horticultural crops [

12,

13,

17]. Reviews by Rodrigues et al. and Malécange et al. indicate that such biostimulants frequently induce measurable improvements in leaf greenness and canopy development, particularly under abiotic stress conditions, although most studies rely on ground-based physiological measurements rather than remote sensing indicators [

12,

17]. Domínguez et al. further emphasized that fish-derived hydrolysates can promote plant metabolic recovery and water-use efficiency, supporting their suitability for integration into sustainable, circular-economy-oriented agricultural systems [

23].

Compared with these studies, the present work extends existing knowledge by quantitatively linking UAV-derived NDVI metrics with post-harvest canopy recovery in citrus under hyper-arid coastal conditions and by explicitly evaluating the contribution of an on-farm, residue-based organic biostimulant. This integration of high-resolution remote sensing with biostimulant-based management represents a methodological advance over previous citrus studies, which have rarely combined objective UAV indicators with adaptive post-harvest interventions in perennial fruit systems.

While the observed increases in NDVI and related canopy vigor metrics are consistent with improved canopy conditions during the post-harvest recovery period, it is important to note that the NDVI represents a proxy of canopy greenness and structure rather than a direct measurement of underlying physiological processes. In this study, nutrient uptake, chlorophyll concentration, and plant water status were not measured directly; therefore, mechanistic interpretation is presented cautiously. The enhanced canopy recovery observed in treated trees may reflect a faster restoration of photosynthetically active foliage and overall canopy function following harvest, potentially supported by the nutrient and bioactive composition of the residue-based biostimulant. However, confirming the specific physiological pathways involved requires dedicated measurements, such as leaf nutrient analysis, chlorophyll-related indices or fluorescence, and plant water status indicators, which should be addressed in future research.

4.2. Temporal Changes in Canopy Condition and Treatment Effects

During the pre-treatment period (Flights 1 and 2), treated and control plots showed broadly comparable canopy NDVI distributions and summary metrics, confirming that the two groups were effectively balanced before any intervention. This baseline similarity was expected because the residue-based biostimulant was not applied until after Flight 2; therefore, Flights 1–2 captured orchard dynamics under identical commercial management conditions, without the influence of treatment. Between Flight 2 and Flight 3, the biostimulant was applied exclusively to the eight treated plots via fertigation through the pressurized drip irrigation system (four applications on 1, 8, 15, and 22 August 2025; ~1 L tree−1 per application; ~4 L per tree−1 cumulative), while control plots received no biostimulant and all other agronomic practices remained unchanged.

Against the backdrop of this design, the strong separation observed at Flight 3 is best interpreted as a treatment-driven response rather than a continuation of pre-existing differences [

22,

55]. Specifically, after harvest (24 July 2025), the control plots displayed a lower vigor signal, consistent with post-harvest recovery demands, whereas the treated plots exhibited a clear rightward shift in NDVI and a markedly larger high-vigor canopy fraction. Taken together, these patterns indicate that the residue-based biostimulant conferred a measurable advantage during the early post-harvest recovery phase, likely supporting canopy reactivation and accelerating the return to high-vigor NDVI classes, while minimizing the decline observed in untreated trees [

56,

57].

4.3. Statistical Strength and Design Features Supporting Inference

The statistical significance of the treatment effects was robust, with two-sided tests for Flight 3 yielding

p-values < 0.0001 for both the canopy NDVI and high-vigor canopy fraction [

19,

58]. These results are further supported by the experimental design, which employed a randomized complete block design (RCBD) to minimize the influence of environmental gradients and ensure the reliable attribution of observed treatment effects, as widely recommended in modern experimental design frameworks [

59]. In addition, the application of NDVI-based canopy masks allowed the isolation of canopy pixels from soil, inter-row areas, and shaded zones, thereby reducing the potential bias associated with mixed pixels and edge effects. Previous UAV-based studies in perennial cropping systems have demonstrated that canopy masking and pixel-level aggregation substantially improve the sensitivity and reliability of vegetation indices when evaluating treatment-induced differences in canopy vigor [

52]. Together, these methodological features enhance confidence in the observed treatment effects and support the conclusion that the detected differences were primarily driven by the biostimulant application.

4.4. Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Despite the strong findings, several limitations should be considered. While the NDVI is a powerful metric for assessing canopy vigor, it can saturate at high canopy densities, which may reduce sensitivity to additional gains once the canopy reaches very high vigor [

34,

60]. Future studies should, therefore, consider complementary vegetation indices less prone to saturation (e.g., red-edge-based indices, when available) to strengthen physiological interpretation [

34,

60,

61]. In addition, the monitoring design included a limited number of UAV acquisitions and a single post-treatment observation; extending the time series would help to determine whether treatment effects persist, intensify, or diminish beyond the early post-harvest recovery window.

In addition, it should be acknowledged that NDVI and related canopy vigor metrics represent indirect proxies of canopy condition rather than direct measurements of plant physiological processes. In this study, parameters such as nutrient uptake, chlorophyll concentration, and plant water status were not measured directly; therefore, mechanistic interpretation of the observed canopy recovery patterns is necessarily limited. While the NDVI-based response observed in treated trees is consistent with improved canopy function during the post-harvest recovery period, confirming the underlying physiological mechanisms would require dedicated measurements, including leaf nutrient analyses, chlorophyll-related metrics, and indicators of plant water status. In this context, the inclusion of complementary spectral indices such as the EVI, GNDVI, NDMI, or MSI would allow future studies to disentangle chlorophyll-related dynamics and plant water status during post-harvest recovery.

Moreover, this study focused on remotely sensing the canopy condition, and further research is needed to determine whether the observed increases in canopy NDVI and high-vigor fraction translate into measurable improvements in yield, fruit quality, and marketability. Although canopy vigor is often considered a useful predictor of tree performance, direct agronomic and post-harvest measurements are required to confirm production-level outcomes.

Importantly, fruit quality parameters—including fruit size, firmness, soluble solid content, and external or internal quality attributes—were not evaluated in this study. Consequently, any potential effects of the observed post-harvest canopy recovery on fruit quality cannot be inferred from the present data and should be addressed explicitly in future research.

Practical constraints of the on-farm, residue-based biostimulant include insect attraction during preparation and application, which may hinder routine farm-scale use. Future implementations should optimize handling conditions (e.g., hermetic containers and controlled fermentation) to reduce odors and insect activity. In addition, the variable availability of farm-derived inputs across seasons may limit scalability and standardization unless sourcing and formulation are more tightly controlled [

60,

62].

4.5. Implications and Future Research Directions

Future research directions emerging from this study highlight the need to expand UAV-based assessments of post-harvest citrus recovery beyond single-index approaches. Building upon the present findings, future work should integrate multi-index UAV frameworks that combine structural indicators of canopy recovery (e.g., NDVI) with complementary spectral indices sensitive to chlorophyll dynamics and plant water status (e.g., EVI, GNDVI, NDMI, MSI). In addition, the incorporation of red-edge-based vegetation indices should be considered in future studies to overcome the known saturation limitations of the NDVI at high canopy densities and to improve sensitivity to subtle post-harvest canopy changes. Such an integrated approach would allow a more comprehensive interpretation of post-harvest recovery processes, facilitating the distinction between structural canopy reactivation and underlying physiological and hydric responses. Moreover, coupling multi-index UAV monitoring with ground-based measurements of leaf nutrient status, chlorophyll-related traits, and plant water status would strengthen mechanistic understanding and improve the evaluation of biostimulant-driven recovery under hyper-arid, water-limited citrus production systems.

The findings of this study have important implications for citrus growers, particularly in regions with arid or semi-arid climates such as La Yarada Los Palos. Using an organic biostimulant offers a low-cost, sustainable solution to enhance post-harvest recovery, improve canopy health, and potentially increase fruit yield and quality. Given the increasing pressures on agriculture to adopt sustainable practices, biostimulants represent a promising tool to reduce dependency on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides while promoting plant health.

Future research should extend these findings by monitoring the long-term effects of biostimulants on citrus trees, particularly in terms of yield and fruit quality. Additional studies should also investigate the optimal timing and frequency of biostimulant applications to maximize efficacy. Furthermore, integrating biostimulants with other precision agriculture technologies, such as soil moisture sensors and automated irrigation systems, could offer synergistic benefits for sustainable citrus production in water-limited environments.

From a sustainability perspective, the observed post-harvest canopy recovery patterns reinforce the role of UAV-based monitoring as a decision-support tool for strengthening the resilience of citrus production systems under water-limited conditions, directly contributing to SDG 2 (Zero Hunger). The use of an on-farm, residue-based organic biostimulant aligns with SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by promoting the valorization of locally available agricultural and fishery residues within a circular economy framework, with clear implications for low-cost and locally adaptable management strategies. Furthermore, the integration of data-driven crop monitoring under hyper-arid conditions contributes to SDG 13 (Climate Action) by enabling adaptive management approaches and providing a scalable foundation for future research aimed at improving climate resilience in citrus agroecosystems.