Investment Efficiency–Risk Mismatch and Its Impact on Supply-Chain Upgrading: Evidence from China’s Grain Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Theoretical Basis and Measurement Methods of Enterprise Investment Efficiency

2.2. Multi-Dimensional Construction and Comprehensive Assessment of Enterprise Investment Risks

2.3. The Driving Mechanism for the Upgrading of the Grain Supply Chain

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Method

3.1.1. Three-Stage DEA Method

3.1.2. PCA Method

3.1.3. Efficiency–Risk Quadrant Classification

3.2. Variable Definition and Source

3.2.1. Sample Selection

3.2.2. Variable Definitions

- Selection of Input and Output Variables

- Environmental Variable

- Investment Risk Variable

3.2.3. Descriptive Statistics

4. Data Analysis and Empirical Results

4.1. Investment Efficiency Analysis

4.1.1. Stage I: Initial BCC Efficiency Estimation

4.1.2. Stage II: SFA Regression on Input Slacks

4.1.3. Stage III: Adjusted Efficiency After External Factor Correction

4.2. Investment Risk Analysis

4.2.1. Principal Component Risk Structure and Enterprise Risk Distribution Characteristics

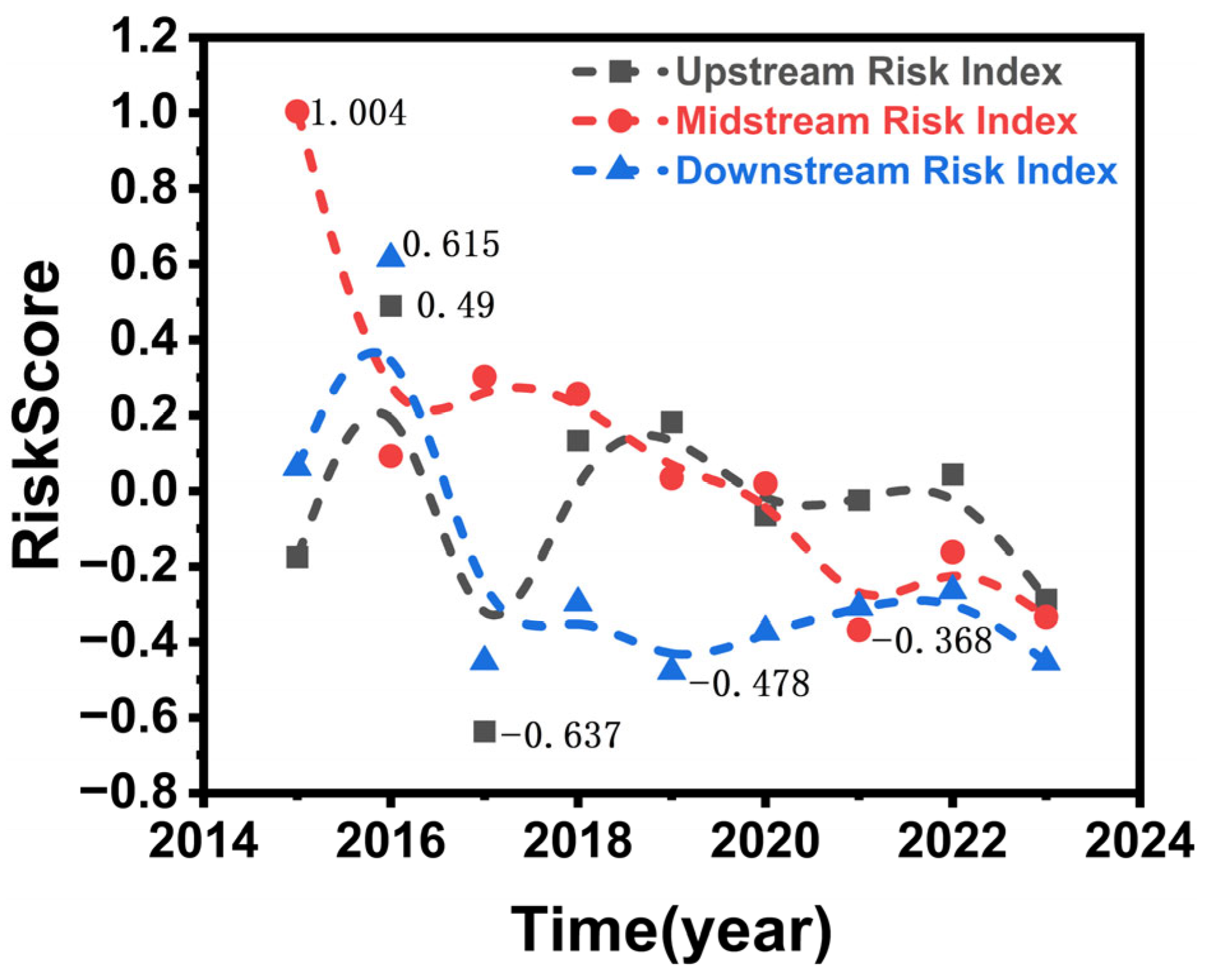

4.2.2. Investment Risk Evolution and Segment-Specific Risk Profiles

4.3. Joint Impact Analysis

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion of Main Findings

5.2. Theoretical Significance

5.3. Practical Significance

5.3.1. Upstream Segment

5.3.2. Midstream Segment

5.3.3. Downstream Segment

5.4. Limitations and Prospects

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DEA | Data Envelopment Analysis |

| SFA | Stochastic Frontier Analysis |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| GVC | Global Value Chain |

| SO | Scale Output |

| CPA | Capital Input |

| OC | Operating Cost Input |

| PE | Period Expenses Input |

| LAB | Labor Input |

| SIZE | Firm Size |

| AGE | Firm Age (Years Since Listing) |

| PGDP | Per Capita Gross Domestic Product |

| OWNC | Ownership Concentration |

| HHI | Herfindahl–Hirschman Index |

| Lev | Leverage Ratio (Total Liabilities/Total Assets) |

| EM | Equity Multiplier |

| Liquid | Current Ratio |

| CashFlow | Cash Flow Ratio |

| ROE | Return on Equity |

| ROA | Return on Assets |

| NPG | Net Profit Growth Rate |

| Rec | Accounts Receivable Ratio |

| Inv | Inventory Ratio |

| crete | Comprehensive Investment Efficiency |

| vrete | Pure Technical Efficiency |

| scale | Scale Efficiency |

| LR | Likelihood Ratio |

| NBS | National Bureau of Statistics of China |

| MIIT | Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China |

| CSMAR | China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database |

| WIND | Wind Financial Database |

References

- Gereffi, G. Global value chains and international development policy: Bringing firms, networks and policy-engaged scholarship back in. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2019, 2, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Subramanian, N.; Singh, R.K.; Venkatesh, M. Digital capabilities to manage agri-food supply chain uncertainties and build supply chain resilience during compounding geopolitical disruptions. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 44, 1914–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, T.J. Upgrading strategies for industrial value chains: Firm decisions and structural constraints. Ind. Corp. Change 2021, 30, 343–367. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, N. The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica 2009, 77, 623–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, T.J.; Prasada Rao, D.S.; O’donnell, C.J.; Battese, G.E. An Introduction to Efficiency and Productivity Analysis; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bozoğlu, M.; Ceyhan, V. Measuring the technical efficiency and exploring the inefficiency determinants of vegetable farms in Samsun province, Turkey. Agric. Syst. 2007, 94, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Su, X.; Wang, R. Exploring the measurement of regional forestry eco-efficiency and influencing factors in China based on the super-efficient DEA-tobit two stage model. Forests 2023, 14, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.H.; Azhari, A. The performance and corporate risk-taking of firms: Evidence from Malaysian agricultural firms. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 12, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Shi, P. Regional rural and structural transformations and farmer’s income in the past four decades in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 13, 278–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, W. Agricultural production networks and upgrading from a global–local perspective: A review. Land 2022, 11, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.J. The measurement of productive efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1957, 120, 253–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Son, J.; Kim, C.; Chung, K. Efficiency measurement using data envelopment analysis (DEA) in public healthcare: Research trends from 2017 to 2022. Processes 2023, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 130, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, K.; Song, D.W.; Wang, T. The application of mathematical programming approaches to estimating container port production efficiency. J. Product. Anal. 2005, 24, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrouznejad, A.; Yang, G. A survey and analysis of the first 40 years of scholarly literature in DEA: 1978–2016. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2018, 61, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, H.O.; Lovell, C.A.K.; Schmidt, S.S.; Yaisawarng, S. Accounting for environmental effects and statistical noise in data envelopment analysis. J. Product. Anal. 2002, 17, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, D.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H. Regional ecological efficiency and future sustainable development of marine ranch in China: An empirical research using DEA and system dynamics. Aquaculture 2021, 534, 736339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, V.; Vale, J.; Bertuzi, R.; Bandeira, A.M.; Palhares, J. A two-stage DEA model to evaluate the performance of Iberian Banks. Economies 2021, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wan, K.; Wang, D. Evaluation of green transformation efficiency in Chinese mineral resource-based cities based on a three-stage DEA method. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, J. Does the digital economy enhance green total factor productivity in China? The evidence from a national big data comprehensive pilot zone. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2024, 69, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismailov, T.; Honcharova, I.; Radukanov, S.; Kabakchieva, T. Digital Technology Management and Resource Efficiency in Agricultural Production. Econ. Ecol. Socium 2025, 9, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, S.M.; Mousavi Shiri, M. The role of corporate governance in investment efficiency and financial information disclosure risk in companies listed on the Tehran stock exchange. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.M.; Tran, Q.T. Corruption and corporate investment efficiency around the world. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 31, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.; Lu, Y. Corporate Sustainability Performance and Liquidity: International Evidence. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.F.; Zhang, X.F. Analyze agricultural efficiency and influencing factors base on the three-stage DEA model and Malmquist index. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1633859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Chen, X. The impact of data factor-driven industry on the green total factor productivity: Evidence from the China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y. China’s agricultural green total factor productivity based on carbon emission: An analysis of evolution trend and influencing factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Yang, M.; Wu, X.; Pu, J.; Izui, K. Evaluating and analyzing the efficiency and influencing factors of cold chain logistics in China’s major urban agglomerations under carbon constraints. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Liu, T. Impact of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency on Contract Farming Coverage and Regional Differences: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Lee, J. Economic and social upgrading in global value chains and industrial clusters: Why governance matters. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wen, X.; Sun, Y.; Xiong, Y. Impact of agricultural product brands and agricultural industry agglomeration on agricultural carbon emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Yan, J.; Mohsin, M.; Mehak, A. Supply chain risks in agri-food systems: A comprehensive review of economic vulnerabilities and mitigation approaches. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1649834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfaoui, R.; Goodell, J.W.; Mefteh-Wali, S.; Chishti, M.Z.; Gozgor, G. Impact of climate risk shocks on global food and agricultural markets: A multiscale and tail connectedness analysis. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 93, 103206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, C.; Raineau, Y.; Raynal, M.; Pasquier, N. Multiple agricultural risks and insurance—Issues, perspectives, and illustration for wine-growing. Rev. Agric. Food Environ. Stud. 2024, 105, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihrete, T.B.; Mihretu, F.B. Crop diversification for ensuring sustainable agriculture, risk management and food security. Glob. Chall. 2025, 9, 2400267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, W.H.; McNichols, M.F.; Rhie, J.W. Have financial statements become less informative? Evidence from the ability of financial ratios to predict bankruptcy. Rev. Account. Stud. 2005, 10, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Wong, E.Y.C.; Sun, M.; Wang, Z. Multidimensional financial metrics for corporate financial risk assessment and early warning mechanisms. J. Organ. End User Comput. (JOEUC) 2024, 36, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, V.V.; Pedersen, L.H.; Philippon, T.; Philippon, T. Measuring systemic risk. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2017, 30, 2–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I. Principal component analysis. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 1094–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.; Cui, J.; Jo, H. Corporate environmental responsibility and firm risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 563–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiong, J.; Sun, M.; Wang, J. Risk assessment for cropland abandonment in mountainous area based on AHP and PCA—Take Yunnan Province in China as an example. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fu, Y. Prediction of supply chain financial credit risk based on PCA-GA-SVM model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporin, M.; Garcia-Jorcano, L.; Jimenez-Martin, J.A. Early warnings of systemic risk using one-minute high-frequency data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhrohtun, Z.; Salim, M.Z.; Sunaryo, K.; Astuti, S. Returns co-movement and interconnectedness: Evidence from Indonesia banking system. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2023, 11, 2226903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G. International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. J. Int. Econ. 1999, 48, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Humphrey, J.; Sturgeon, T. The governance of global value chains. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2005, 12, 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.; Schmitz, H. How does insertion in global value chains affect upgrading in industrial clusters? Reg. Stud. 2002, 36, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G. Economic upgrading in global value chains. In Handbook on Global Value Chains; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Zhang, R.; Di, D.; Li, G. Does digital transformation promote global value chain upgrading? Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Econ. Model. 2024, 139, 106810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q. The impact of global value chain embedding on the upgrading of China’s manufacturing industry. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1256317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, Z. The impact of agricultural global value chain participation on agricultural total factor productivity. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Harman, O. Climbing Up Global Value Chains: Leveraging FDI for Economic Development; Hinrich Foundation: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kergroach, S. National innovation policies for technology upgrading through GVCs: A cross-country comparison. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 145, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Abdullah, M.A. Impact of Industrial Agglomeration on the Upgrading of China’s Automobile Industry: The Threshold Effect of Human Capital and Moderating Effect of Government. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, L.; Tsang, E.W.K.; Yeung, H.W. Global value chains: A review of the multi-disciplinary literature. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2020, 51, 577–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melitz, M.J. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 2003, 71, 1695–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.B.; Jensen, J.B.; Redding, S.J.; Schott, P.K. The empirics of firm heterogeneity and international trade. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2012, 4, 283–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Shi, H.; Luo, W.; Liu, B. Productivity, financial constraints, and firms’ global value chain participation: Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2018, 73, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Saeidi, P.; Raj Mishra, A. Assessment of the agriculture supply chain risks for investments of agricultural small and mediumsized enterprises (SMEs) using the decision support model. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2023, 36, 2126991. [Google Scholar]

- Imbiri, S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Chileshe, N.; Statsenko, L. A novel taxonomy for risks in agribusiness supply chains: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honcharuk, I.; Chikov, I.; Okhota, Y.; Biletska, N. Strategic Management and ESG Impact Assessment in Sustainable Agribusiness Development Model. Econ. Ecol. Socium 2025, 9, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Ramanujam, V. Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Becchetti, L.; Bedoya, D.A.L.; Paganetto, L. ICT investment, productivity and efficiency: Evidence at firm level using a stochastic frontier approach. J. Product. Anal. 2003, 20, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camanho, A.S.; Silva, M.C.; Piran, F.S.; Lacerda, D.P. A literature review of economic efficiency assessments using Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 315, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, O.; Frýd, L. DEA efficiency in agriculture: Measurement unit issues. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 86, 101497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Tang, D.; Kong, H.; He, J. An analysis of agricultural production efficiency of Yangtze river economic belt based on a three-stage DEA Malmquist model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Loecker, J.; Van Biesebroeck, J. Effect of International Competition on Firm Productivity and Market Power; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Ma, H.; Huang, J.; Hu, R.; Rozelle, S. Productivity, efficiency and technical change: Measuring the performance of China’s transforming agriculture. J. Product. Anal. 2010, 33, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Yao, P. Can development of large scale agricultural business entities improve agricultural total factor productivity in China? An empirical analysis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1281328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, S.; Pedersen, T. Ownership structure and economic performance in the largest European companies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olalere, O.E.; Mukuddem-Petersen, J. Product market competition, corporate investment, and firm value: Scrutinizing the role of economic policy uncertainty. Economies 2023, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Xu, J.F.; Fareed, Z.; Wan, G.; Ma, L. Financial leverage and corporate innovation in Chinese public-listed firms. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seretidou, D.; Billios, D.; Stavropoulos, A. Integrative Analysis of Traditional and Cash Flow Financial Ratios: Insights from a Systematic Comparative Review. Risks 2025, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Le, T.D.Q. The interrelationships between bank profitability, bank stability and loan growth in Southeast Asia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2084977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzala, R.W.; Obokoh, L. The effects of working capital management on the financial performance of commercial and service firms listed on the Nairobi Securities Exchange in Kenya. Risks 2024, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Huang, G. Measuring systemic risk contribution: A higher-order moment augmented approach. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 59, 104833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Timmer, C.P. The economics of the food system revolution. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2012, 4, 225–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinnen, J.; Kuijpers, R. Value chain innovations for technology transfer in developing and emerging economies: Conceptual issues, typology, and policy implications. Food Policy 2019, 83, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, S.; Baek, Y. Impacts of firm’s GVC participation on productivity: A case of Japanese firms. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2022, 66, 101232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, S. Impact of economic policy uncertainty on corporate investment efficiency: Moderating roles of financing constraints and financialisation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J. The role of associated risk in predicting financial distress: A case study of listed agricultural companies in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 77, 107125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, N.E.; Fuglie, K.O. New perspectives on farm size and productivity. Food Policy 2019, 84, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, A. The Effect of Land Fragmentation on Risk and Technical Efficiency of Austrian Crop Farms. J. Agric. Econ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F.; Bloem, J.R. Does contract farming improve welfare? A review. World Dev. 2018, 112, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable Name | Symbol | Variable Description | Unit | Mean | Sd | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input Variables | Capital Investment | CPA | Net fixed assets + capital expenditures | 100 million CNY | 19.203 | 26.009 | 0.875 | 164.014 |

| Operating Cost Investment | OC | Operating revenue × (1 − gross profit margin) | 100 million CNY | 282.152 | 890.018 | 0.902 | 5266.734 | |

| Period Cost Investment | PE | Operating revenue × (operating expense ratio + management expense ratio) | 100 million CNY | 10.370 | 39.094 | 0.001 | 253.652 | |

| Labor Investment | LAB | ln(number of employees) | - | 7.761 | 1.160 | 4.615 | 10.566 | |

| Output Variables | Scale Output | SO | Operating revenue + operating profit | 100 million CNY | 301.003 | 916.158 | −2.202 | 5429.613 |

| Environmental Variables | Firm Size | SIZE | ln(total assets) | - | 22.426 | 1.110 | 20.725 | 25.589 |

| Listing Year | AGE | Current year − year of establishment + 1 | Years | 18.840 | 6.243 | 4.000 | 32.000 | |

| Per Capita GDP | PGDP | Annual per capita GDP of the region | 10,000 CNY | 6.812 | 3.307 | 2.595 | 20.028 | |

| Ownership Concentration | OWNC | Shareholding ratio of the largest shareholder | % | 33.788 | 15.951 | 9.131 | 64.143 | |

| Market Competition Level | HHI | Herfindahl–Hirschman Index of the industry | - | 0.174 | 0.167 | 0.016 | 1.000 | |

| Leverage Risk | Asset–Liability Ratio | Lev | Total debt/total assets | % | 0.481 | 0.214 | 0.059 | 1.290 |

| Equity Multiplier | EM | Total assets/total equity | - | 3.538 | 13.353 | 1.063 | 187.114 | |

| Liquidity Risk | Current Ratio | Liquid | Current assets/current liabilities | - | 1.832 | 1.296 | 0.285 | 9.978 |

| Cash Flow Ratio | CashFlow | Cash equivalents/current liabilities | - | 0.072 | 0.069 | 0.000 | 0.528 | |

| Profitability and Volatility Risk | Return on Equity | ROE | Net profit/shareholder equity | % | 0.318 | 3.034 | 0.001 | 45.551 |

| Net Profit Growth Rate | NPG | (Current period net profit − previous period net profit)/previous period net profit | % | 1.836 | 4.896 | 0.004 | 48.322 | |

| Return on Assets | ROA | Net profit/total assets | % | 0.049 | 0.045 | 0.001 | 0.301 | |

| Operational Risk | Accounts Receivable Ratio | Rec | Accounts receivable/operating revenue | % | 0.054 | 0.036 | 0.001 | 0.182 |

| Inventory Ratio | Inv | Inventory/operating revenue | % | 0.207 | 0.112 | 0.022 | 0.484 |

| Supply-Chain Segment | Indicator | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream | crete | 0.262 | 0.297 | 0.319 | 0.296 | 0.030 | 0.285 | 0.395 | 0.448 | 0.500 | 0.315 |

| vrete | 0.824 | 0.837 | 0.837 | 0.786 | 0.065 | 0.780 | 0.810 | 0.816 | 0.845 | 0.733 | |

| scale | 0.315 | 0.357 | 0.382 | 0.375 | 0.041 | 0.372 | 0.482 | 0.537 | 0.589 | 0.383 | |

| Midstream | crete | 0.302 | 0.356 | 0.401 | 0.482 | 0.528 | 0.570 | 0.608 | 0.569 | 0.553 | 0.485 |

| vrete | 0.789 | 0.789 | 0.801 | 0.779 | 0.736 | 0.790 | 0.814 | 0.785 | 0.802 | 0.787 | |

| scale | 0.362 | 0.434 | 0.482 | 0.573 | 0.652 | 0.663 | 0.701 | 0.672 | 0.633 | 0.575 | |

| Downstream | crete | 0.739 | 0.865 | 0.879 | 0.655 | 0.649 | 0.684 | 0.766 | 0.814 | 0.797 | 0.761 |

| vrete | 1.000 | 0.996 | 0.945 | 0.865 | 0.824 | 0.864 | 0.907 | 0.922 | 0.935 | 0.918 | |

| scale | 0.739 | 0.867 | 0.915 | 0.716 | 0.732 | 0.754 | 0.814 | 0.853 | 0.819 | 0.801 | |

| Overall Mean | crete | 0.434 | 0.506 | 0.533 | 0.478 | 0.402 | 0.513 | 0.590 | 0.610 | 0.617 | 0.520 |

| vrete | 0.472 | 0.553 | 0.593 | 0.555 | 0.475 | 0.596 | 0.666 | 0.687 | 0.680 | 0.586 | |

| scale | 0.871 | 0.874 | 0.861 | 0.810 | 0.542 | 0.811 | 0.844 | 0.841 | 0.861 | 0.813 |

| Variables | Input(CPA) Slack | Input(OC) Slack | Input(PE) Slack | Input(LAB) Slack |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −86.507 *** (−4.86) | −54.918 * (−1.670) | −0.248 (−0.359) | −0.407 (−0.208) |

| Env(SIZE) | 3.700 *** (4.447) | 2.502 (1.523) | −0.014 (0.404) | 0.035 (0.365) |

| Env(AGE) | 0.363 ** (2.4853) | 0.412 (1.4489) | −0.004 (−0.6732) | 0.060 *** (3.7277) |

| Env(PGDP) | −0.000 *** (−5.476) | −0.000 *** (−2.696) | −0.001 * (−1.808) | −0.000 *** (−5.211) |

| Env(OWNC) | 26.148 *** (5.901) | 18.669 * (1.923) | 0.442 ** (2.342) | 1.996 *** (3.351) |

| Env(HHI) | −3.003 (−0.892) | −5.124 (−0.608) | −0.123 (−0.703) | 0.031 (0.065) |

| 432.309 *** (3.057) | 24,810.371 *** (52.056) | 34.640 *** (3.559) | 5.076 *** (3.291) | |

| 0.962 *** (71.687) | 0.991 *** (1068.488) | 0.997 *** (1232.763) | 0.933 *** (44.309) | |

| Log | −681.153 *** | −996.982 *** | −127.645 *** | −237.825 *** |

| LR | 304.022 *** | 748.355 *** | 860.574 *** | 259.669 *** |

| Supply- Chain Segment | Indicator | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Mean | Change Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream | crete | 0.102 | 0.108 | 0.275 | 0.093 | 0.108 | 0.100 | 0.107 | 0.121 | 0.146 | 0.129 | −59.05 |

| vrete | 0.960 | 0.968 | 0.870 | 0.948 | 0.934 | 0.934 | 0.930 | 0.929 | 0.917 | 0.932 | 27.15 | |

| scale | 0.106 | 0.113 | 0.291 | 0.093 | 0.115 | 0.107 | 0.118 | 0.134 | 0.168 | 0.138 | −63.97 | |

| Midstream | crete | 0.228 | 0.255 | 0.277 | 0.328 | 0.344 | 0.349 | 0.349 | 0.325 | 0.316 | 0.308 | −36.49 |

| vrete | 0.939 | 0.933 | 0.930 | 0.909 | 0.904 | 0.901 | 0.895 | 0.894 | 0.892 | 0.911 | 15.76 | |

| scale | 0.236 | 0.266 | 0.288 | 0.348 | 0.368 | 0.371 | 0.372 | 0.348 | 0.336 | 0.326 | −43.30 | |

| Downstream | crete | 0.525 | 0.552 | 0.635 | 0.633 | 0.642 | 0.655 | 0.682 | 0.698 | 0.676 | 0.633 | −16.82 |

| vrete | 0.993 | 1.000 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 0.987 | 0.985 | 0.988 | 0.988 | 0.992 | 8.06 | |

| scale | 0.526 | 0.552 | 0.636 | 0.633 | 0.643 | 0.657 | 0.685 | 0.700 | 0.678 | 0.634 | −20.85 | |

| Overall Mean | crete | 0.285 | 0.305 | 0.396 | 0.351 | 0.365 | 0.368 | 0.379 | 0.381 | 0.379 | 0.357 | −37.45 |

| vrete | 0.964 | 0.967 | 0.931 | 0.952 | 0.943 | 0.941 | 0.937 | 0.937 | 0.932 | 0.945 | 16.99 | |

| scale | 0.289 | 0.310 | 0.405 | 0.358 | 0.375 | 0.378 | 0.392 | 0.394 | 0.394 | 0.366 | −42.71 |

| Variable | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lev | 0.762 | −0.542 | −0.064 | 0.063 | 0.074 |

| EM | 0.581 | −0.236 | 0.212 | −0.481 | −0.462 |

| Liquid | −0.608 | 0.526 | 0.203 | −0.071 | −0.312 |

| CashFlow | 0.079 | 0.189 | −0.627 | −0.513 | 0.431 |

| ROE | 0.846 | 0.325 | 0.056 | −0.038 | −0.135 |

| NetProfitGrowth | 0.492 | 0.497 | 0.038 | 0.372 | 0.118 |

| ROA | 0.438 | 0.751 | −0.048 | 0.224 | 0.028 |

| Rec | 0.052 | −0.198 | 0.764 | 0.025 | 0.498 |

| Inv | −0.036 | −0.475 | −0.375 | 0.591 | −0.161 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.448 | 1.844 | 1.215 | 1.044 | 0.808 |

| Variance Explained (%) | 27.198 | 20.487 | 13.501 | 11.605 | 8.979 |

| Cumulative Variance Explained (%) | 27.198 | 47.685 | 61.186 | 72.790 | 81.769 |

| Key Empirical Result | Identified Bottleneck | Segment-Specific Measure | Expected Mechanism | Primary Target Audience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream firms exhibit persistently low investment efficiency, mainly driven by scale inefficiency rather than pure technical inefficiency (Table 4; three-stage DEA results). | Structural scale inefficiency combined with high-risk exposure discourages long-term factor inflows. | Promote scale-enhancing land consolidation, cooperative/contract farming, and scale-oriented service platforms, combined with risk-buffer instruments. | Improve scale organization and reduce efficiency–risk mismatch, thereby restoring incentives for sustained capital, labor, and technology investment. | Policy makers; upstream producers; agricultural service providers |

| Midstream firms show improving efficiency but pronounced risk volatility over time (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7), limiting the sustainability of efficiency gains. | Efficiency–risk mismatch caused by unstable risk expectations. | Develop risk-stabilizing supply-chain finance, inventory and warehouse-receipt financing, and digitally enabled contract coordination. | Stabilize risk expectations, allowing efficiency gains to translate into long-horizon upgrading investments. | Financial institutions; midstream processors; supply-chain managers |

| Downstream firms consistently operate in a high-efficiency and low-risk regime and cluster in favorable efficiency–risk configurations (Table 4; Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). | Stability is not effectively transmitted upstream and midstream. | Leverage downstream lead firms through market-based coordination mechanisms (long-term procurement contracts, quality standards, and data-sharing incentives). | Transmit stability upstream, reduce system-wide efficiency–risk mismatch, and promote coordinated upgrading along the supply chain. | Lead firms; regulators; platform operators |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Meng, F.; Li, B.; Li, Y. Investment Efficiency–Risk Mismatch and Its Impact on Supply-Chain Upgrading: Evidence from China’s Grain Industry. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031293

Liu Z, Meng F, Li B, Li Y. Investment Efficiency–Risk Mismatch and Its Impact on Supply-Chain Upgrading: Evidence from China’s Grain Industry. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031293

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zihang, Fanlin Meng, Bingjun Li, and Yishuai Li. 2026. "Investment Efficiency–Risk Mismatch and Its Impact on Supply-Chain Upgrading: Evidence from China’s Grain Industry" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031293

APA StyleLiu, Z., Meng, F., Li, B., & Li, Y. (2026). Investment Efficiency–Risk Mismatch and Its Impact on Supply-Chain Upgrading: Evidence from China’s Grain Industry. Sustainability, 18(3), 1293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031293