1. Introduction

Cultural heritage has increasingly emerged as a driver of local economic development, shaping tourism dynamics, creative industries, community livelihoods, place identity, and urban regeneration across historic towns and regions. As government and international organizations position heritage as a strategic asset for sustainable development, understanding the economic behaviour of heritage systems has gained growing relevance. The cultural heritage economy is inherently multidimensional, encompassing the conservation and management of heritage assets, visitor behaviour, local business performance, dissemination of cultural value, and interactions with broader urban and regional economies [

1]. These components operate through complex direct, indirect, induced, and intangible linkages, making heritage-led development both an opportunity and a planning challenge. Yet, compared to other domains of urban and regional analysis, the heritage economy remains less systematically modelled.

A persistent challenge relates to anticipating how heritage resources translate into economic outcomes over time. Heritage planning has traditionally relied on descriptive assessments, qualitative evaluations, and conservation-oriented frameworks that prioritize cultural values, while offering limited insight into evolving economic dynamics. In parallel, mainstream urban economic studies have tended to understate the role of heritage and socio-cultural processes in shaping development trajectories. Although tourism forecasting and economic impact models such as Input–Output (I-O), Computable General Equilibrium (CGE), and Tourism Satellite Accounts (TSAs) [

2,

3] have been applied in heritage contexts, their focus is often confined to visitor volumes or aggregate impacts. Similarly, heritage management frameworks such as UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach and culture-led regeneration models provide valuable conceptual guidance [

4] but are not designed to support predictive economic analysis. As a result, heritage towns often navigate socio-economic decision-making without integrated tools capable of capturing the dynamic interplay between heritage assets, economic processes, and spatial development patterns.

Within this context, predictive modelling offers a complementary approach for understanding and managing the cultural heritage economy. Heritage towns increasingly engage with fluctuating visitation, conservation expenditure, entrepreneurial activity, community expectations, and long-term economic sustainability under conditions of uncertainty. Predictive modelling enables structured, evidence-based exploration of how heritage-related variables interact with social, physical, and economic systems over time, supporting more informed planning and policy decisions. In the absence of such anticipatory approaches, heritage-led development risks becoming reactive, fragmented, or unsustainable, with implications for both cultural integrity and economic resilience.

Existing modelling efforts in heritage and culture-led development have largely focused on isolated components, such as tourism impact assessment, heritage valuation indices, or indicator-based evaluation frameworks. While these approaches provide valuable insights into economic effects, they typically do not integrate heritage attributes, social processes, physical infrastructure, and economic conditions within a single predictive structure. This emphasizes the lack of integrated or widely recognized predictive models for the cultural heritage economy, as existing approaches address isolated components rather than the system as a whole. Current modelling techniques remain fragmented across tourism forecasting, economic assessment, heritage management and spatial planning, with limited frameworks capable of integrating behavioural, economic, cultural and spatial variables dynamically. Heritage-specific drivers, such as conservation quality, authenticity perception, cultural significance, and community participation, are seldom incorporated into forecasting tools, and most studies rely on descriptive or static analyses with minimal predictive validation. As a result, planners lack robust decision-support mechanisms to test scenarios and anticipate the economic implications of heritage interventions. The present study extends this body of work by proposing and empirically validating a system-oriented model that evaluates predictive relevance across interconnected dimensions of the cultural heritage economy. These gaps motivate the research questions guiding this study:

How can the cultural heritage economy be conceptualized as a dynamic system with interlinked economic, cultural, behavioural, and spatial components?

What key variables and indicators meaningfully predict the economic performance and development trajectories of heritage towns?

How can a predictive modelling framework integrate these variables to support evidence-based heritage planning and promote sustainable urban development?

The motivation for this research arises from the growing emphasis on heritage-led development and the increasing need for analytical tools that can anticipate economic outcomes in heritage towns. While existing studies offer valuable insights through tourism forecasting, economic impact assessment, and heritage management frameworks, these approaches typically address isolated aspects of the heritage economy. Given the complex interactions between cultural value, visitor behaviour, local enterprises and spatial conditions, planners require modelling approaches that synthesize these dimensions into a coherent predictive structure. This study responds to that need by advancing an integrative predictive model tailored to the unique dynamics of cultural heritage economies. The aim of this study is to develop a comprehensive and integrative predictive modelling framework for the cultural heritage economy, enabling the systematic analysis and forecasting of economic performance, development trajectories, and heritage-driven urban dynamics. The objectives of this study are as follows:

To identify key variables and indicators that characterize and predict the functioning of the cultural heritage economy.

To develop the construct operationalization framework that organizes these variables into measurable and interpretable components.

To formulate an integrative predictive modelling framework that applies these operationalized constructs to support evidence-based heritage planning and sustainable urban development.

The envisioned outcome of this study is a theoretically grounded, reproducible, and analytically robust predictive model tailored to the cultural heritage economy. The model is developed and validated using expert-elicited data, with the objective of establishing a theory-building, predictive structural framework for heritage-led local economic development that can subsequently be operationalized with town-level data in applied planning contexts. The model is expected to provide planners, policymakers and researchers with a decision-support tool capable of forecasting economic trends, evaluating development scenarios, and guiding sustainable heritage-led urban planning.

In practical terms, the proposed model can be applied as a decision-support framework in heritage planning contexts characterized by competing development pressures. For example, it can be used to assess whether investments in tourism infrastructure without parallel social activation are likely to yield economic returns, to evaluate the anticipated economic implications of culture–tourism integration projects, or to identify leverage points for enhancing community participation in heritage-led development. By revealing the sequential pathways through which heritage resources translate into revenue generation, the model supports more informed coordination between conservation priorities, infrastructure provision, and local economic strategies. Ultimately, it seeks to enhance the understanding of how cultural heritage functions as a driver of local economic development and to support more proactive, evidence-informed management of heritage towns.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides the background and reviews existing literature on cultural heritage economies, tourism-based economic assessment, and the role of modelling in heritage planning. This is followed by an articulation of the knowledge gaps, research questions, and theoretical contributions of the study.

Section 3 presents the methodological design, model components, and development process, followed by discussion of conceptual model development in

Section 4 and statistical validation of the model in

Section 5.

Section 6 highlights the implications of this research in a theoretical, managerial, and research perspective.

Section 7 concludes with the theoretical contribution of this model for planning practice and highlights the limitations and scope for future research.

2. Review of Literature

Understanding how cultural heritage generates economic value requires a multidisciplinary theoretical foundation that spans across cultural economics, tourism studies, behavioural science, urban development and regeneration theory. Cultural heritage does not merely function as preserved artifacts but also plays an active economic resource embedded in social, cultural, and spatial systems. Its value arises through multiple channels, such as inflow of tourism, local enterprise development, creative industries, community participation, identity formation, and place-based competitiveness. These channels are underpinned by diverse theoretical perspectives that explain how individuals perceive, engage with, and derive meaning from heritage; how heritage assets stimulate market and non-market economic benefits; and how cultural environments shape urban development trajectories. Collectively, the theories provide the conceptual basis for identifying the core components of the cultural heritage economy, as discussed in

Section 2.1, and thereby are used to define the constructs that can be operationalized to develop the predictive modelling framework (

Section 4 and

Section 5).

2.1. Theoretical Perspectives on How Cultural Heritage Generates Economic Value

Cultural economics theory conceptualizes heritage as a form of cultural capital, a public asset that generates both market and non-market value. Cultural assets generate quantifiable economic benefits through tourism, employment, and local enterprise development, while also creating intangible value involving place-identity, symbolic meaning, and social cohesion [

5]. David Throsby’s cultural capital framework identified heritage as a durable asset that delivers long-term flows of cultural and economic value, making it a critical component of regional development strategies. The heritage value framework developed by R. Mason distinguishes between use value (tourism, creative consumption), non-use value (existence, perception value), and socio-cultural value (identity, meaning, memory, and association). This approach [

6] argues that heritage value is multi-dimensional and embedded in social processes, influencing how communities and visitors engage with heritage assets, and it established that this plurality of values shapes spending behaviour, willingness to pay, and the distribution of economic benefits in heritage towns. The tourism-led growth theory (TLGH) postulates that tourism stimulates broader economic development through income generation, employment, and foreign exchange earnings, and can have a rippling effect on multidimensional sectors such as commerce, transportation, utility, and hospitality and creative industries [

7]. In this case, on the basis of this theory, it can be inferred that heritage tourism often generates higher economic multipliers because visitors typically spend more and stay longer.

In 1998, Pine and Gilmore proposed the Experience Economy Theory, which hypothesizes that economic value increasingly derives from experiences rather than products and services [

8]. This pattern can be observed in heritage destinations, which deliver experiential value through authenticity, immersion, cultural narratives, and emotional engagements. With respect to heritage economies, this theory explains visitor decision-making, satisfaction, and spending patterns, which eventually predict the economic outputs. Another theory focusing on the authenticity of experiences was put forth by Mac Cannell in 1973, who introduced the idea of staged authenticity, suggesting that tourists seek genuine cultural experiences but often encounter curated representations [

9]. It was established that perceived authenticity influences destination image, visitor motivation, willingness to pay, and ultimately economic performance [

10].

Community participation theories emphasize that heritage-led development is more sustainable and equitable when local communities play active roles in planning, decision-making, and cultural production. High levels of participation enhance local ownership, build social capital, and stimulate community-based enterprises [

11]. This contributes significantly to local economic resilience. At the same time, the place-based development theory argues that unique territorial assets, such as heritage, landscape, culture, and identity, form the foundation for endogenous economic growth [

12]. Heritage towns must leverage these assets to differentiate themselves, attract visitors, and develop distinctive local economies. In addition to these, the culture-led regeneration views heritage and cultural assets as catalysts for revitalizing urban areas, attracting investment, stimulating creative industries, enhancing liveability, and improving socio-economic conditions [

13].

The cultural heritage economy is thus shaped by a wide spectrum of interrelated factors that extend far beyond heritage assets alone. Its drivers include social dynamics, physical and infrastructural conditions, creative and economic activities, governance support, and the wide-ranging market environment that surrounds heritage sites. These dimensions interact in complex ways to influence how heritage contributes to local development, revenue generation, community well-being, and long-term sustainability. To capture this multi-layered structure, the cultural heritage economy can be understood through a comprehensive set of indicators, as listed in

Table 1, that range from intrinsic heritage attributes to socio-economic outcomes and enabling economic conditions.

When looking at these strands of literature, together, they suggest that heritage-led development operates as a system rather than through isolated mechanisms. Cultural capital and heritage value frameworks establish the foundational significance of heritage resources, while tourism and experience-economy perspectives explain how heritage is mobilized through social interaction and consumption. Community participation highlights the mediating role of social processes in activating heritage value, and urban systems theory emphasizes the importance of physical and economic infrastructures in enabling these processes to translate into measurable development outcomes. However, existing studies tend to examine these dimensions independently. This fragmentation motivates this study’s integrative approach, which conceptualizes the cultural heritage economy as a system linking heritage resources, social by-products, physical by-products, and economic conditions to revenue generation. Building on these interrelated theoretical perspectives,

Table 1 synthesizes the dimensions and parameters of the cultural heritage economy identified from the literature. These parameters have not been assigned fixed causal roles at this stage, as their functional position (e.g., enabling condition, mediating process, or outcome) may vary across analytical contexts and is subsequently specified through construct development and structural modelling.

While the parameters listed in

Table 1 span multiple dimensions of the cultural heritage economy, their relevance lies not in isolated effects but in their expected interdependencies. Heritage resources provide the foundational cultural capital of a place, but their influence on development outcomes is mediated through social processes such as participation, cultural activity, and tourism engagement. These social by-products, in turn, generate demand for physical infrastructure and services, which enable the translation of heritage value into economic conditions such as employment, entrepreneurship, and investment. Accordingly, the hypothesized relationships are derived from a sequential logic in which social and physical dimensions act as enabling mechanisms linking heritage resources to economic outcomes, rather than as independent drivers. The functional positioning of these parameters as antecedents, mediators, or outcomes is analytically refined through expert validation, dimensionalization, and hypothesis development in

Section 3 and

Section 4.

2.2. Predictive Modelling in Urban Planning and Development

Predictive modelling in urban planning is grounded in a rich theoretical tradition that attempts to understand how cities evolve and develop through interactions between spatial, economic, demographic, and behavioural systems. These models differ from descriptive or assessment approaches because they explicitly aim to forecast future scenario of urban systems and assess the impacts of planning interventions. The following theories form the conceptual basis for predictive modelling in planning and also offer methodological insights relevant for cultural heritage economies.

Urban systems theory conceptualizes cities as complex, adaptive systems composed of interconnected subsystems such as population, economy, transportation, land use, and governance [

40]. Changes within one subsystem generate feedback effects across others, producing non-linear and emergent outcomes. This perspective underscores the need for predictive approaches that capture dynamic interdependencies rather than treating urban components in isolation, supporting the use of system-based and scenario-oriented modelling frameworks in urban analysis.

The Land-Use and Transportation Interaction (LUTI) theory provides a foundational basis for predictive modelling in planning by conceptualizing land use and transportation as mutually reinforcing systems. Land use patterns shape travel behaviour, while accessibility conditions influence location choices, land values, and development intensity, producing reciprocal dynamics over time [

41]. LUTI-based models demonstrate how economic activity, spatial accessibility, and development processes can be integrated within a coherent predictive framework, supporting system-oriented approaches to urban analysis [

42].

Agent-Based Modelling (ABM) is rooted in complex adaptive systems theory and micro-level behavioural decision-making, simulating interactions among autonomous agents such as households, firms, tourists, and institutions. System-level patterns emerge from these micro-level interactions as agents operate under heterogeneous preferences, bounded rationality, and adaptive behaviour [

43]. In urban contexts, ABM has been widely applied to examine land use change, mobility patterns, and local economic responses, making it particularly suitable for modelling behavioural dynamics and spatial-economic interactions [

44].

The System Dynamics (SD) theory, introduced by Forrester, conceptualizes cities as feedback-driven systems governed by interacting stocks such as population, jobs, housing supply, etc., and flows including migration, investment, and consumption. SD models are particularly valuable for predicting long-term trends, thresholds, and non-linear behaviours, including sustainability, capacity limits, and resource depletion [

45].

Spatial interaction theory explains flows, primarily of people, goods, and services, between origins and destinations based on attractiveness and distance impedance. For predictive modelling, these theories help understand how accessibility and spatial structure influence behaviour [

46].

Modern predictive modelling builds on statistical learning theory, which provides the foundation for algorithms that detect patterns in data and make forecasts. Techniques such as regression, ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average), neural networks, random forests, gradient boosting, and deep learning enable prediction of complex, non-linear phenomena in urban systems [

47]. The concept of machine learning (ML) is theoretically grounded in function approximation, pattern recognition, error minimization, and generalization under uncertainty [

48]. In urban planning, these models predict land use change, real estate values, mobility trends, and visitor demand and sustainable urban management.

An approach of scenario planning and anticipatory governance has come into play recently, grounded in future studies and anticipatory governance that argue that decision makers and planners must prepare for multiple plausible futures rather than rely on individual deterministic forecast and planning [

49,

50]. Scenario-based predictive modelling allows the evaluation of policy interventions, infrastructure changes, conservation investments, shocks (pandemics, environmental events), and market fluctuations.

2.3. Significant Learning and Research Gaps

These studies demonstrate that the cultural heritage economy is multidimensional, shaped by interactions among heritage assets, visitor behaviour, community engagement, spatial and infrastructural conditions, and wider economic systems. Cultural economics and heritage value theories highlight the coexistence of market and non-market benefits, while experiential and authenticity theories emphasize behavioural drivers that influence spending and destination choice. Spatial theories emphasize the role of accessibility and built form in shaping flows, and development theories position heritage as a catalyst for local economic growth. Predictive modelling approaches such as LUTI, ABM, System Dynamics, and machine learning reveal the potential for forecasting complex urban processes. However, they have been seldom applied holistically to heritage contexts. Despite these insights, the following gaps persist:

Fragmented analytical approaches: existing studies examine tourism, heritage value, spatial factors, or economic impacts in isolation, with limited integration across domains.

Need for dynamic predictive frameworks, as there is no comprehensive model that captures social, cultural, infrastructural, economic, and governance interactions to forecast heritage-driven economic outcomes.

Underrepresentation of heritage-specific variables: Indicators such as authenticity, conservation quality, cultural significance, and community participation are rarely operationalized within economic predictive models.

Insufficient decision-support tools for planners, limiting assessing the future implications of conservation strategies, mobility improvements, or investments, using scenario-based models.

These gaps collectively justify the need for a comprehensive, integrative predictive modelling framework for the cultural heritage economy, enabling systematic analysis and forecasting of economic performance, development trajectories, and heritage-driven urban dynamics. The next section outlines the methodological steps used for the conceptual development of the measurement model.

3. Research Methodology

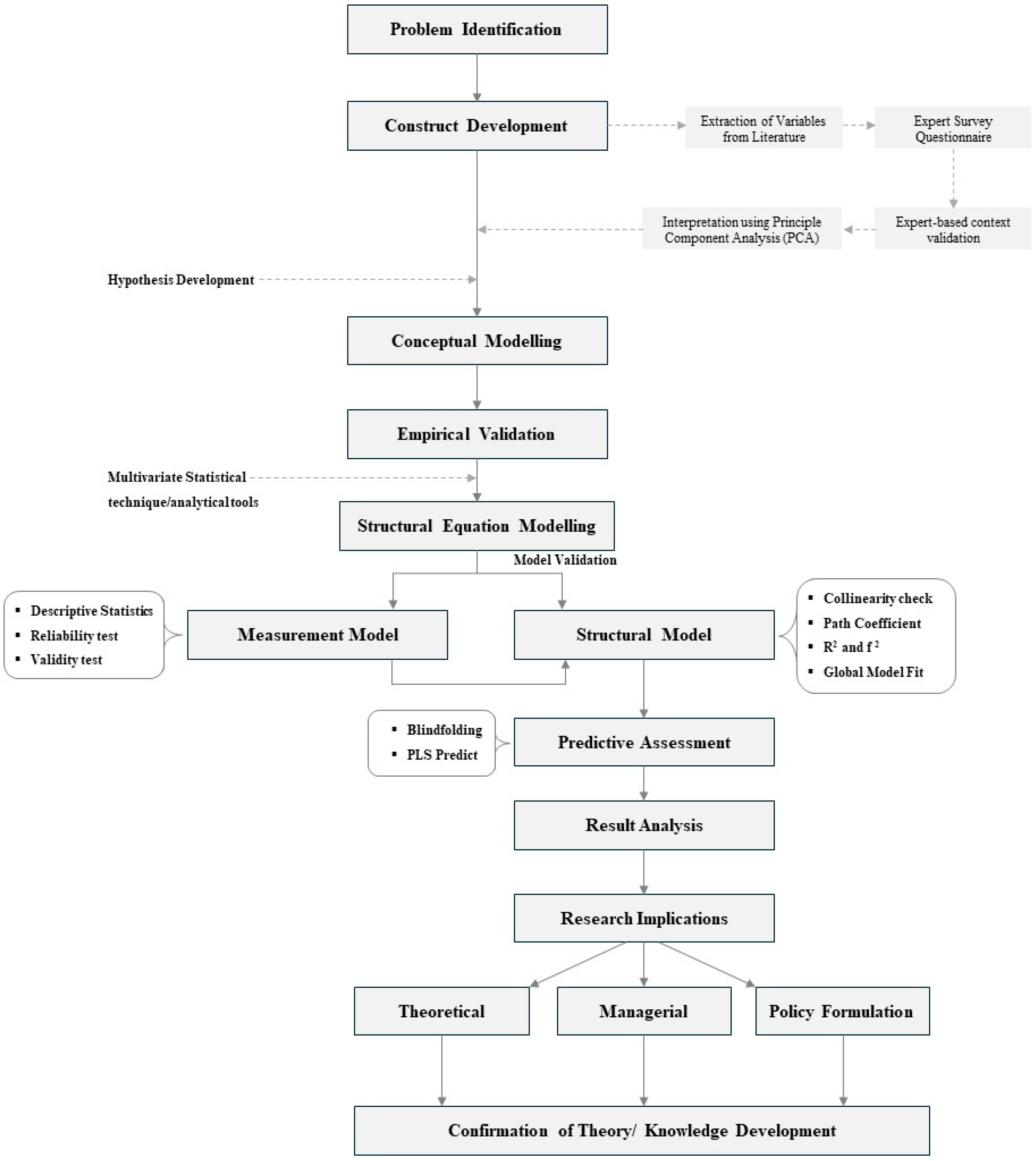

The methodological design adopted in this study follows a structured, sequential process that moves from conceptual development to empirical validation, culminating in predictive assessment and research implications, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.1. Problem Identification

The process begins with problem identification, through which the need for an integrative predictive framework for the cultural heritage economy is established, on the basis of an extensive literature review.

3.2. Construct Development and Expert Validation

This is followed by construct development, where 33 relevant parameters and indicators are extracted from an extensive literature review (as shown in

Table S1), which is then refined and validated using expert surveys. The use of expert opinion provides content validity and ensures that constructs reflect domain-specific relevance. A three staged Delphi technique has been used for this indicator-based study, having a structured multistage framework (

Figure S1). This technique enables anonymous expert consultation and controlled feedback to achieve consensus, offering advantages in structured decision-making and reduced individual bias. PCA was subsequently applied to validate the latent structure of the refined parameters, eliminate redundancy, and empirically support dimensions of Cultural Heritage Economy [

51]. The combined expert-driven and data-driven approach enhances methodological robustness, reliability, and contextual relevance for heritage towns [

51].

Experts were selected based on education and professional experience, having a minimum undergraduate degree and five years of practice in heritage, planning, architecture, economics, or academia. The survey questionnaire was distributed to 80 professionals with clear information on research aims, with voluntary participation. Informed consent was obtained from all experts prior to participation. Participation was entirely voluntary, with the option to withdraw at any stage, and no personally identifiable or sensitive data were collected as part of the survey. A three-staged Delphi technique was conducted, having (a) Stage 1 (parameter elimination; 61 responses, 76.25%), (b) Stage 2 (revised parameter rating using Saaty’s scale [

52]; 49 responses, 80.32%), and (c) Stage 3 (final parameter rating; 45 responses, 91.83%). The professional composition of the respondents was found to be diverse—Heritage Experts (10.81%), Economists (8.10%), Urban Planners (24.32%), Architects (29.18%), and Academicians/Researchers (17.56%). Nearly 45% held postgraduate degrees, 30% were doctoral-level experts, and the rest possessed significant professional experience [

51].

Consensus thresholds were defined prior to analysis to guide parameter retention and refinement across Delphi rounds. Parameters demonstrating consistently high central tendency (median ≥ 4 on a five-point scale) and acceptable dispersion were retained, while parameters showing persistent disagreement or conceptual overlap were either merged or excluded following expert feedback. Disagreement between rounds was addressed through controlled feedback, allowing experts to reconsider their ratings in light of anonymized group responses, consistent with established Delphi practice.

Parameters exhibiting relatively higher dispersion or lower initial agreement were not automatically excluded; instead, they were retained for subsequent rounds where experts were provided with anonymized group feedback and invited to reassess their ratings. This iterative process allowed convergence to be evaluated across rounds, with final inclusion based on conceptual relevance and stabilization of expert judgement rather than single-round thresholds. The detailed overview of the respondents is represented in

Figure S2. The varied academic, technical, and practice-based perspectives ensured a comprehensive outcome of the Delphi process.

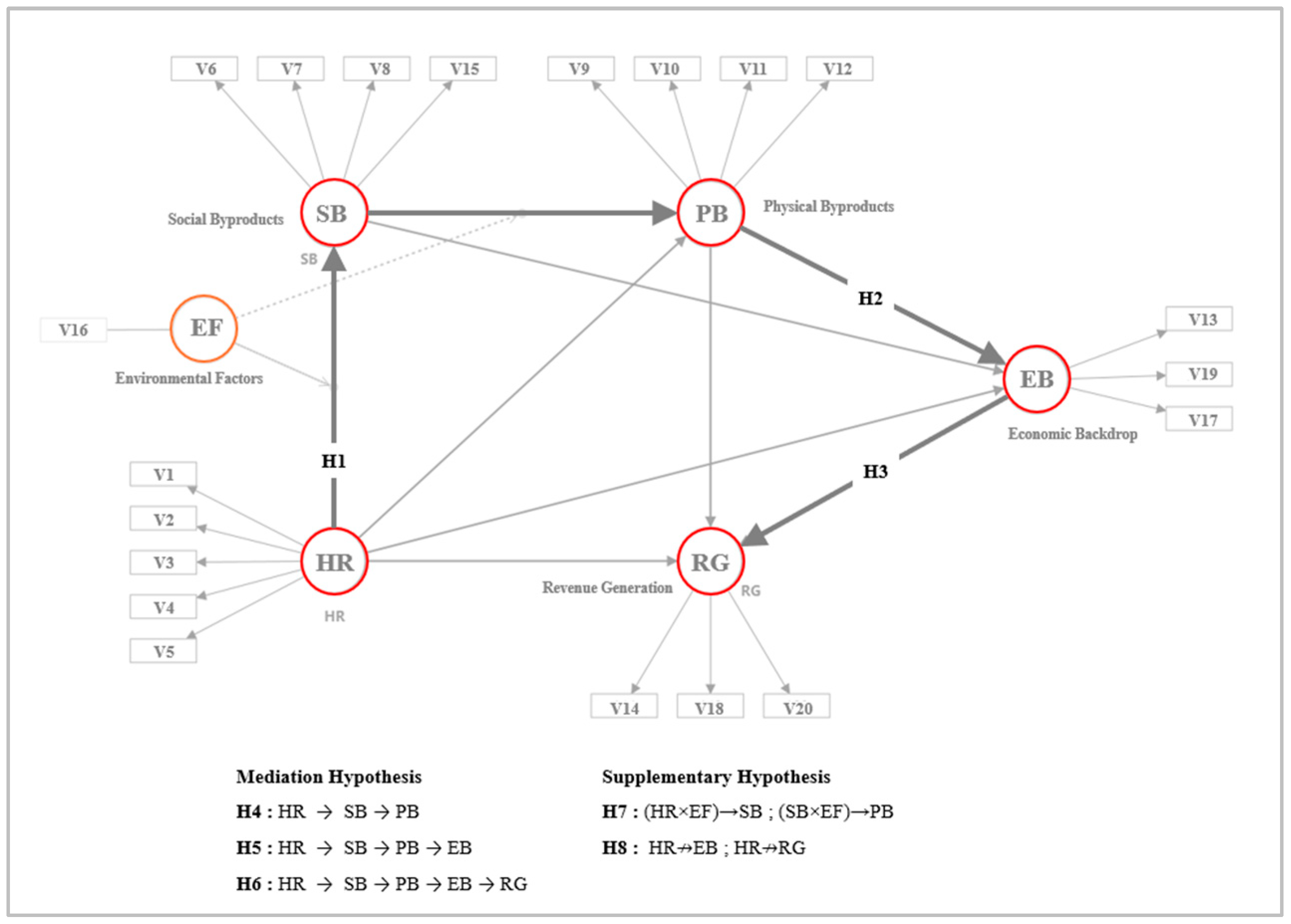

3.3. Conceptual Modelling

The insights inferred from the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) form the basis for strengthened empirical grounding of the constructs, enabling the interpretation of factor structures and reduced dimensionality. Building on these validated constructs, the next stage involves conceptual modelling, where theoretical linkages among constructs are articulated and hypotheses are developed to explain the proposed relationships, as explained in

Section 4.

3.4. Empirical Validation

Accordingly, the empirical validation of the proposed model is based on construct development and expert-elicited data, consistent with the objective of theory development and structural prediction rather than town-specific economic forecasting.

This conceptual foundation transitions into empirical validation, where multivariate statistical methods are employed to test the measurement and structural components of the model. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), specifically PLS-SEM, is selected due to its suitability for exploratory research, its flexibility in handling complex models with formative and reflective constructs, robustness with small-to-medium sample sizes, which are common in heritage-focused research contexts, and its prediction-oriented modelling character. Within SEM, the assessment initiates with the measurement model, which evaluates indicator reliability, internal consistency, convergent validity and discriminant validity. This step ensures that each construct is measured accurately before testing causal relationships. The structural model is then assessed to examine collinearity, path coefficients, explained variance (R2), effect sizes (f2), and overall model fit, steps that collectively determine the strength and significance of the proposed relationships. To evaluate the model’s forecasting ability, a predictive assessment is conducted using blindfolding and the PLSpredict algorithm, enabling the estimation of cross-validated redundancy and out-of-sample predictive accuracy.

3.5. Proposed Research Implications

Model validation and results interpretation provide a basis for deriving research implications across theoretical, managerial, and policy domains. These findings contribute to theory development and knowledge advancement, demonstrating how the proposed predictive framework advances understanding of heritage-driven economic systems and offers comprehensive practical tools for planning and policy formulation.

5. Analysis and Results

This section presents and discusses the empirical results obtained from the Structural Equation Modelling (SEM-PLS) analysis using SmartPLS 4, Latest Version (v4.0.9.9). Following the two-step approach as discussed in

Section 3, the measurement model is first evaluated to establish reliability and validity, followed by an assessment of the structural model to test the hypothesized relationships, mediation effects, and predictive performance. The findings interpret the significant relationships and lead to the proposed Cultural Heritage Economy Model.

5.1. Measurement Model

The measurement model was evaluated to ensure the adequacy of the constructs prior to testing the structural relationships. This assessment involved descriptive analysis, reliability testing, and validity testing in accordance with established SEM-PLS guidelines [

58].

5.1.1. Descriptive Analysis

At first, the descriptive statistics are examined to understand the distributional properties of the indicators associated with each construct, including Heritage Resources (HR), Social By-products (SB), Physical By-products (PB), Economic Backdrop (EB), Environmental Factors (EF) and Revenue Generation (RG). Measures of central tendency and dispersion are used to assess response consistency and overall data quality.

As shown in

Table 2, the mean values across indicators range from 3.73 to 4.78, indicating generally high expert agreement on the relevance of the selected parameters, while the standard deviation values are consistently below 1.10, which falls well within acceptable limits for Likert-scale expert data and reflects low dispersion and strong response consistency. Methodologically, standard deviation values below 1.50 are considered indicative of stable measurement in perception-based studies, particularly those relying on expert judgement [

58]. Skewness values across indicators are predominantly negative, with most falling within the recommended range of ±3 in social science studies, and they are also tolerated in PLS-SEM. The negative skewness, as observed in

Table 2, indicates a concentration of responses toward the higher end of the scale, which can be expected in expert validated studies where parameters have already been screened through literature review and Delphi consensus. Kurtosis values largely remain within acceptable bounds, well below the conservative threshold of ±7, indicating the absence of extreme peaked-ness or heavy-tailed distributions [

59]. Altogether, the skewness and kurtosis statistics do not indicate problematic non-normality. Moreover, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) does not require strict adherence to multivariate normality assumptions, unlike covariance-based SEM. PLS-SEM is explicitly suited for expert-driven, ordinal-scale data and remains robust under conditions of moderate skewness and kurtosis. The examination of descriptive distributional properties indicates that the data meet accepted criteria for subsequent PLS-SEM analysis.

5.1.2. Reliability Tests

Internal consistency reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (ρc), which assess the degree to which indicators consistently represent their underlying latent constructs. Cronbach’s alpha reflects the lower-bound estimate of reliability based on inter-item correlations, while composite reliability accounts for the standardized loadings of individual indicators and is therefore considered more suitable for PLS-SEM applications [

58]. An initial assessment of construct reliability included Environmental Factors (EF) based on theoretical relevance. However, EFs did not satisfy minimum reliability thresholds, indicating insufficient internal consistency, as shown in

Table 4. Consequently, EF was excluded from subsequent structural model estimation to ensure robustness of the final model.

As presented in

Table 5, all constructs in the final model exceed the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating satisfactory reliability. Heritage Resources and Economic Backdrop exhibit very high reliability values, reflecting the strong internal coherence of their indicators. This indicates that while item intercorrelations are moderate, the construct exhibits adequate reliability once indicator loadings are considered. Constructs including Heritage Resources (HR) and Economic Backdrop (EB) display Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values of 1.000. Such values reflect near-perfect inter-item consistency and are typically observed in constructs comprising a small number of highly correlated, expert-validated indicators. The exclusion of Environmental Factors (EF) in the final mode reflects measurement limitations rather than a dismissal of their conceptual importance.

In PLS-SEM, particularly within expert-based and composite-oriented models, these values do not indicate redundancy or estimation problems but rather reflect strong conceptual coherence within the construct. Overall, all retained constructs meet or exceed recommended reliability criteria, confirming that the measurement model exhibits sufficient internal consistency to support subsequent convergent validity assessment and structural model estimation.

5.1.3. Validity Tests

Convergent Validity

Convergent validity was assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) criterion, which evaluates the extent to which a latent construct explains the variance of its indicators relative to measurement error. An AVE value of 0.50 or higher indicates adequate convergent validity, signifying that the construct captures more than half of the variance in its observed measures [

60].

As presented in

Table 6, all retained constructs exceed the recommended AVE threshold. Heritage Resources (HR) exhibit an AVE of 0.998, indicating exceptionally strong convergence between the construct and its indicators. This reflects the high conceptual coherence of heritage-related indicators derived from expert validation and literature synthesis. Economic Backdrop (EB) records an AVE of 1.000, suggesting near-perfect alignment between its indicators and the underlying construct, a result commonly observed in expert-based models with a limited number of highly correlated economic indicators [

60]. Social By-products (SB) and Physical By-products (PB) report AVE values of 0.877 and 0.885, respectively, demonstrating strong convergent validity while preserving meaningful heterogeneity within social and physical dimensions. These values indicate that the constructs effectively capture the variance associated with socio-cultural engagement and infrastructural attributes in heritage contexts. Revenue Generation (RG) also achieves a high AVE value of 0.863, confirming that its indicators adequately represent the underlying revenue construct.

Overall, the AVE results confirm that all constructs retained in the final model exhibit robust convergent validity, providing strong empirical support for the adequacy of the measurement model and justifying progression to discriminant validity assessment and structural model evaluation.

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity has been assessed using both the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) and the Fornell–Larcker criterion, in line with current best practices for PLS-SEM. The HTMT ratio evaluates discriminant validity by comparing correlations across constructs, with values below 0.85 (or more conservatively, 0.90) indicating adequate discriminant validity [

58]. As shown in

Table 7, all HTMT values in the model range between 0.151 and 0.608, well below the recommended threshold. Specifically, relationships involving Heritage Resources (HR) with other constructs exhibit low HTMT values (e.g., HR–EB = 0.151, HR–SB = 0.402, HR–PB = 0.512, HR–RG = 0.428), indicating that heritage attributes are empirically distinct from social, physical, and economic dimensions.

Similarly, Social By-products (SB) and Physical By-products (PB) demonstrate moderate HTMT values (SB–PB = 0.460), suggesting related but non-overlapping constructs. The HTMT values associated with Revenue Generation (RG) remain comfortably below threshold (e.g., RG–EB = 0.608, RG–PB = 0.483, RG–SB = 0.281), confirming that revenue outcomes are empirically separable from upstream system components. Overall, the HTMT results provide strong evidence of discriminant validity across all construct pairs, and the HTMT values were well below both the conservative (0.85) and liberal (0.90) thresholds, confirming discriminant validity.

The discriminant validity is further examined using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which requires that the square root of a construct’s AVE exceed its correlations with all other constructs [

59]. As shown in

Table 8, this condition is satisfied for all constructs in the model. The diagonal elements, representing the square roots of AVE, are 1.000 for EB, 0.999 for HR, 0.828 for PB, 0.823 for SB, and 0.603 for RG, each of which exceeds the corresponding inter-construct correlations. For example, the square root of AVE for Physical By-products (PB) (0.828) is higher than its correlations with HR (0.473), EB (0.546), SB (0.408), and RG (0.568). These results confirm that each construct shares more variance with its own indicators than with other constructs in the model.

The HTMT and Fornell–Larcker results consistently indicate that the constructs in the final model are empirically distinct. The measurement model therefore demonstrates robust discriminant validity, supporting the conceptual separation of Heritage Resources, Social By-products, Physical By-products, Economic Backdrop and Revenue Generation within the Cultural Heritage Economy Model.

5.2. Structural Model

After establishing the adequacy of the measurement model, the structural model was evaluated to test the hypothesized relationships among constructs and to assess the explanatory power of the proposed Cultural Heritage Economy Model. The evaluation focused on the significance of path coefficients, hypothesis testing, mediation effects, and the overall performance of the model in explaining revenue generation. Bootstrapping with an appropriate number of resamples was employed to assess the statistical significance of the structural paths, using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), as discussed in

Section 4, with the aid of SmartPLS 4, Latest Version (v4.0.9.9).

5.2.1. Hypothesis Testing

Path coefficients (β), along with their corresponding t-values and

p-values of the hypothesized relationships of the structural model, were estimated using a bootstrapping procedure to evaluate the magnitude, direction, and statistical significance of direct, mediating, and supplementary effects. While β values indicate the strength and direction of relationships between constructs, the associated t- and

p-values, derived from resampled distributions, establish the significance of these relationships [

61]. The significance of the structural relationships was assessed using a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure. The PLS-SEM algorithm was executed using standardized results with a maximum of 3000 iterations, and bootstrapping was performed with 3000 subsamples using a two-tailed test at a 5% significance level, applying the percentile bootstrap confidence interval method. Parallel processing and a fixed random seed were employed to ensure computational efficiency and result reproducibility. This approach enables robust estimation of path coefficients, t-values, and

p-values without imposing distributional assumptions. The hypothesis testing results are presented and interpreted according to three categories, as discussed in

Section 3: direct effects, mediating effects, and supplementary effects (moderation and robustness tests).

Direct Effects

Direct effects examine the primary causal relationships proposed between the latent constructs forming the core structure of the Cultural Heritage Economy Model.

H1: Heritage Resources have a significant positive effect on Social By-products.

The path coefficient from HR to SB was found to be statistically significant, supporting H1. This result indicates that heritage attributes, such as cultural significance, conservation condition, and interpretive value, play a critical role in activating socio-cultural processes, including community participation, awareness, and social engagement. The finding confirms that heritage resources function as a social catalyst, reinforcing the theoretical positioning of heritage as a socio-cultural asset embedded within broader urban systems.

H2: Physical By-products have a significant positive effect on the Economic Backdrop.

H2 was supported, demonstrating that improvements in physical infrastructure such as accessibility, connectivity, and service facilities significantly strengthen and pave the way for an enhanced local economic environment. This result highlights the role of physical systems as enabling mechanisms through which heritage-related activities translate into economic capacity, including business activity, employment opportunities, and investment readiness.

H3: Economic Backdrop has a significant positive effect on Revenue Generation.

The relationship between EB and RG was found to be positive and statistically significant, providing support for H3. This finding confirms that revenue outcomes in heritage contexts are primarily driven by the strength of the local economic environment rather than by heritage assets in isolation. The result reinforces the model’s premise that economic structures act as the final conduit through which upstream social and physical processes yield measurable fiscal outcomes.

Supplementary Effects (Moderation and Robustness Tests)

Supplementary hypotheses were tested to examine contextual moderation effects and to assess the robustness of theoretically expected null relationships.

H7: Environmental Factors moderate (a) the relationship between Heritage Resources and Social By-products, and (b) the relationship between Social By-products and Physical By-products.

H7 was not supported, as the interaction effects (EF × HR → SB and EF × SB → PB) were statistically insignificant. This indicates that environmental conditions do not significantly influence how heritage resources activate social processes or how social engagement translates into physical improvements. The lack of significant moderation effects suggests that the core structural relationships operate consistently across environmental contexts, within the scope of this study.

H8: Heritage Resources have no significant direct effect on Economic Backdrop or Revenue Generation.

The robustness tests proposed in H8 were confirmed. The direct paths from HR to EB and from HR to RG were found to be statistically insignificant, validating the theoretical assumption that heritage resources alone do not generate economic outcomes without intermediary mechanisms. This result strengthens the conceptual integrity of the model by empirically ruling out direct effects and reinforcing the dominance of indirect, system-based pathways.

The results of the structural model and hypothesis testing are summarized in

Table 9. The findings indicate strong support for the proposed direct and mediating relationships, while the supplementary moderation and robustness hypotheses were not supported. Accordingly, effect sizes (f

2) are reported for direct structural relationships, while mediation effects are assessed using bootstrapped indirect path coefficients.

The structural model results indicate that all retained direct paths are statistically significant at the 5% level, with bootstrapped t-values exceeding the critical threshold of 1.96. The strongest effect is observed between the Economic Backdrop (EB) and Revenue Generation (RG) (t = 10.116, p < 0.001), highlighting the central role of economic conditions in driving revenue outcomes. Heritage Resources (HR) exert a significant influence on Social By-products (SB) (t = 3.347, p = 0.001), while Physical By-products (PB) significantly strengthen the Economic Backdrop (EB) (t = 3.376, p = 0.001). The relationship between Social and Physical By-products (SB and PB), though comparatively moderate, remains statistically significant (t = 2.490, p = 0.013), supporting the sequential structure of the model.

Overall, the hypothesis testing results validate the proposed sequential structure of the Cultural Heritage Economy Model. Direct effects confirm the importance of social, physical, and economic linkages; mediating effects establish the layered transmission of heritage value; while the supplementary tests reinforce the robustness of the final model. Altogether, these findings demonstrate that heritage-led Revenue Generation emerges from interconnected socio-cultural, infrastructural, and economic processes rather than from heritage resources in isolation.

5.2.2. Model Performance

Beyond hypothesis testing, the performance of the structural model is evaluated to assess its explanatory power and the relative contribution of exogenous constructs. Model performance was examined using the coefficient of determination (R2) and effect size (f2), following established PLS-SEM evaluation guidelines.

Explanatory Power (R2)

The coefficient of determination (R

2) was used to evaluate the proportion of variance explained in each endogenous construct by its respective predictors. In PLS-SEM, R

2 values of approximately 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 are commonly interpreted as weak, moderate and substantial explanatory power, respectively [

58].

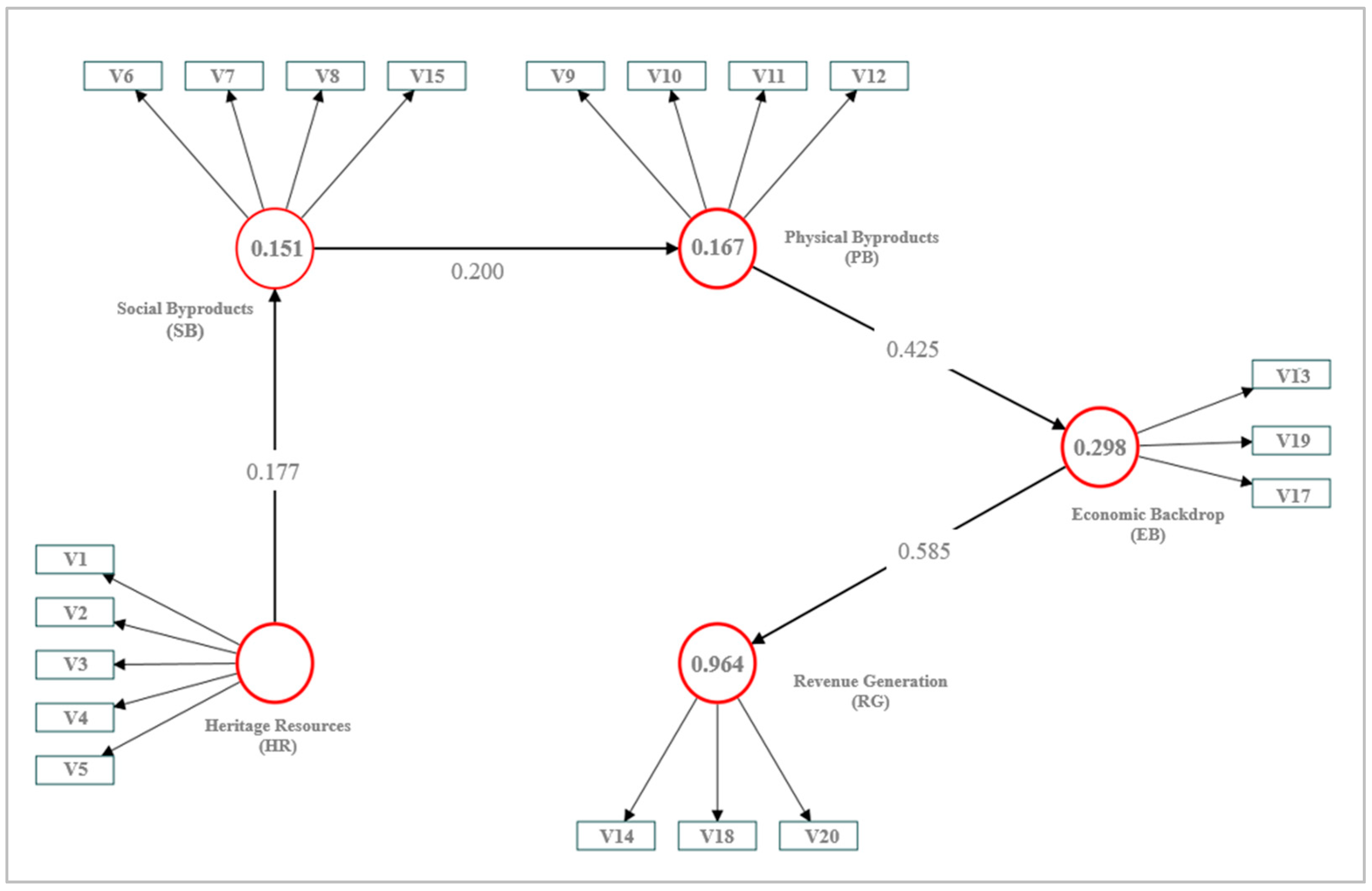

Table 10 presents the coefficient of determination (R

2) values for the endogenous constructs, indicating the explanatory power of the structural model. Social By-products (R

2 = 0.151) and Physical By-products (R

2 = 0.167) exhibit weak-to-moderate explanatory power, reflecting the complex and multi-factor processes involved in translating heritage resources into social and physical outcomes.

The Economic Backdrop shows moderate explanatory power (R2 = 0.298), suggesting that socio-cultural activation and infrastructure improvements contribute meaningfully to local economic conditions. In contrast, Revenue Generation demonstrates substantial explanatory power (R2 = 0.964), confirming that the proposed sequential heritage economy framework effectively explains revenue outcomes. Overall, the R2 pattern supports the cumulative and system-based logic of the model, with explanatory strength increasing along the heritage value chain.

5.2.3. Effect Size (f2)

Effect size (f

2) is examined to assess the relative impact of each exogenous construct on the endogenous variables. The f

2 statistic evaluates how strongly an exogenous construct contributes to the explained variance of an endogenous construct when included in the model. According to established guidelines [

58], f

2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicate small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

Table 11 reports the effect sizes (f

2) of key structural paths, indicating the relative contribution of each predictor to the explanatory power of the endogenous constructs. Heritage Resources exert a medium effect on Social By-products (f

2 = 0.177), while Social By-products show a medium effect on Physical By-products (f

2 = 0.200), highlighting the importance of social activation in translating heritage value into tangible outcomes. The effect of Physical By-products on the Economic Backdrop is large (f

2 = 0.425), underscoring the central role of infrastructure and physical amenities in strengthening local economic conditions. The strongest effect is observed for the relationship between the Economic Backdrop and Revenue Generation (f

2 = 0.585), confirming that economic context is the most influential driver of revenue outcomes within the proposed heritage economy framework.

Overall, the model performance assessment indicates that the proposed Cultural Heritage Economy Model exhibits satisfactory explanatory power and well-distributed effect sizes across its structural paths. The f2 results also indicate that downstream economic pathways exert stronger explanatory influence on the model, with Physical By-products and the Economic Backdrop playing dominant roles in shaping economic outcomes. The results confirm that the sequential configuration of social, physical, and economic mechanisms is not only statistically significant but also substantively meaningful in explaining revenue generation within heritage contexts.

5.2.4. Predictive Relevance

In addition to explanatory power, the predictive capability of the structural model was evaluated to assess its suitability for forward-looking analysis. Predictive relevance was examined using the Stone–Geisser Q

2 statistic obtained through the blindfolding procedure, where Q

2 values greater than zero [

58] indicate meaningful predictive relevance in PLS-SEM.

As shown in

Table 12, all endogenous constructs, Social By-products (Q

2 = 0.756), Physical By-products (Q

2 = 0.805), Economic Backdrop (Q

2 = 0.837), and Revenue Generation (Q

2 = 0.854) exhibit strong positive Q

2 values [

59], confirming the model’s predictive relevance. These results indicate that the structural relationships not only explain observed variance but also possess the capacity to predict unseen observations within the heritage–economy system. The findings support the use of the proposed framework for forward-looking estimation and policy-oriented planning, particularly in contexts where anticipating heritage-driven economic outcomes is essential. Overall, the predictive relevance and PLSpredict results confirm that the Cultural Heritage Economy Model exhibits both in-sample explanatory adequacy and out-of-sample predictive capability. This dual strength supports the use of the model as a robust analytical framework for understanding and anticipating economic outcomes in heritage contexts.

5.3. Interpretation of Validation Findings

The combined results of the measurement and structural model assessments provide strong empirical support for the proposed Cultural Heritage Economy Model. The measurement model confirms that all retained constructs are reliably operationalized and exhibit adequate convergent and discriminant validity, while the structural model establishes a statistically robust system of relationships linking heritage, social, physical, and economic dimensions.

The structural results reveal a clear sequential mechanism through which Heritage Resources contribute to Revenue Generation. Heritage Resources (HRs) significantly influence Social By-products (SBs), highlighting their role in activating community participation, cultural engagement and tourism-related social processes. These social dynamics facilitate the development of Physical By-products (PBs), indicating that infrastructural and built-environment improvements are socially mediated rather than direct outcomes of heritage assets. Physical By-products (PBs), in turn, exert a strong influence on the Economic Backdrop (EB), underscoring the importance of infrastructure quality and functional capacity in strengthening local economic conditions. The Economic Backdrop emerges as the most immediate determinant of Revenue Generation (RG), confirming that revenue outcomes are governed by downstream economic structures rather than heritage attributes alone, as depicted in

Figure 3.

Mediation analysis further strengthens this interpretation by demonstrating full sequential mediation from Heritage Resources to Revenue Generation through Social By-products, Physical By-products, and the Economic Backdrop. The absence of statistically significant direct effects from Heritage Resources to economic or revenue outcomes empirically confirms that heritage value is realized only through layered socio-cultural and infrastructural mechanisms, supporting a system-based understanding of heritage economies and challenging simplified heritage–revenue assumptions. Supplementary analyses provide additional insights into model robustness. The confirmation of null direct effects from Heritage Resources to the Economic Backdrop and Revenue Generation strengthens the internal consistency of the framework by empirically ruling out unsupported causal shortcut effects.

Figure 3 presents the final validated model, illustrating the refined sequential structure following the removal of insignificant paths. From a performance perspective, the model demonstrates satisfactory explanatory power, with R

2 values increasing along the heritage value chain and reaching a substantial level for Revenue Generation. Effect size and predictive relevance assessments further confirm that downstream economic pathways exert the strongest influence and that the model possesses meaningful predictive capability.

Overall, the validation findings confirm that the Cultural Heritage Economy Model offers a robust, empirically grounded framework for explaining how heritage resources translate into economic outcomes through interconnected social, physical, and economic mechanisms. By integrating reliability, validity, explanatory strength, and predictive relevance, the framework advances heritage research beyond descriptive valuation and provides a systematic basis for evidence-based planning and policy formulation in heritage-rich urban contexts.

The statistical results indicate that the economic background construct exerts the strongest direct influence on revenue generation, underscoring the role of enabling economic conditions, such as employment capacity, ease of doing business, and investment support in translating heritage-led activities into measurable financial outcomes. This finding aligns with prior heritage and urban development studies that emphasize the importance of institutional and economic readiness in realizing the benefits of cultural assets. The sequential mediation results further suggest that heritage resources influence revenue generation indirectly, operating through social activation and physical infrastructure provision rather than through direct monetization.

The non-significance of environmental factors as moderators does not imply their irrelevance, but rather points to challenges in operationalizing environmental dimensions within expert-driven structural models. Environmental conditions may function as background constraints or long-term sustainability thresholds rather than as immediate determinants of economic relationships. Additionally, relatively lower R2 values for certain upstream constructs reflect the complexity and context-specific nature of social and cultural processes, which are influenced by factors beyond the scope of the present model. In contrast, higher explanatory power in downstream economic constructs indicates stronger model performance where institutional and economic mechanisms are more clearly defined

6. Implications

This empirically validated model demonstrates how heritage resources translate into economic outcomes through interconnected social, physical, and economic mechanisms; the findings inform conceptual advancement in heritage economics and guide managerial and policy decision-making. The theoretical, managerial and policy, and research implications are discussed in this section.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The study makes several contributions to heritage and urban development theory. First, it advances the conceptualization of cultural heritage economies by moving beyond asset-centric or tourism-focused approaches toward a multidimensional, system-oriented framework. By explicitly modelling Social and Physical By-products as mediating mechanisms, the research demonstrates how heritage value is socially constructed and institutionally realized rather than inherently monetized. Second, the confirmation of full sequential mediation and the rejection of direct heritage–revenue pathways provide empirical evidence against simplified assumptions that heritage assets automatically generate economic returns. This finding strengthens theoretical arguments that heritage economies operate through layered socio-economic processes and reinforces the need to analyse heritage within broader urban systems. Finally, the integration of explanatory and predictive validation positions the model at the intersection of theory-building and applied modelling, contributing to methodological advances in heritage economics and evidence-based planning research. One of the key contributions of this study lies in offering one of the first empirically validated, prediction-oriented structural frameworks that explains heritage-led Revenue Generation as a sequential socio–physical–economic process rather than a direct asset-based outcome.

6.2. Managerial and Policy Implications for Heritage Planning

Heritage-led development is frequently characterized by tensions between conservation objectives and economic growth imperatives, uneven distribution of benefits among local stakeholders, and concerns regarding long-term sustainability. The proposed model does not treat these challenges as isolated trade-offs but frames them as outcomes of how social, physical, and economic mechanisms are coordinated. By revealing the sequential pathways through which heritage resources translate into Revenue Generation, the model provides a structured basis for managing these tensions through integrated planning and policy interventions.

The validated Cultural Heritage Economy Model offers concrete guidance for designing integrated heritage planning and management interventions. Rather than treating heritage conservation, tourism development, and economic growth as separate domains, the model demonstrates how coordinated action across social, physical, and economic dimensions can generate sustained revenue outcomes. At the Heritage Resource (HR) level, planning and heritage management authorities can prioritize conservation and management initiatives that enhance the quality, accessibility, and interpretive value of heritage assets. Conservation-led adaptive reuse, such as converting heritage buildings into cultural centres, co-working spaces, or creative hubs, can preserve cultural value while activating social participation and economic use. At the Social By-product (SB) level, managerial strategies that promote community participation, cultural programming, and experiential tourism become critical. Initiatives such as heritage walks, festivals, craft markets, and storytelling platforms can strengthen visitor engagement while generating employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for local communities. The Physical By-product (PB) dimension highlights the importance of infrastructure-oriented decision-making. Investments in connectivity, pedestrianization, utilities, tourism facilities, and public spaces directly enhance the functional and economic performance of heritage precincts, encouraging longer visitor stays and private-sector participation. At the Economic Backdrop (EB) level, policy instruments such as simplified regulatory approvals, heritage-sensitive zoning, tax incentives, and ease-of-doing-business reforms can translate heritage-led activity into measurable economic gains. Cultural entrepreneurship programmes, creative industry incubators, and heritage-based MSMEs can further reinforce employment generation and investment inflows.

Collectively, these implications reposition heritage areas as managed cultural–economic districts, rather than static conservation enclaves, supporting both fiscal sustainability and long-term heritage protection. The following stakeholder-specific implications outline how different actors can operationalize these system-level insights:

For planning authorities, the model highlights that heritage-led revenue generation cannot be achieved through asset conservation or infrastructure investment alone. The sequential structure demonstrates that social activation and economic enabling conditions are critical intermediaries, suggesting that policies focusing solely on physical upgrading without community engagement or economic facilitation may yield limited returns. The framework can therefore support integrated decision-making across conservation, mobility, tourism, and local economic policy;

For local communities, the findings emphasize the central role of participation and social engagement in translating heritage value into economic outcomes. Community-based cultural activities, local stewardship, and participatory planning processes emerge as essential mechanisms rather than peripheral considerations. The model thus provides an analytical basis for strengthening community participation strategies as a means of enhancing both economic benefits and heritage sustainability;

For enterprises and cultural entrepreneurs, the model clarifies how supportive economic conditions, such as ease of doing business, investment access, and employment generation, mediate the transition from cultural activity to revenue creation. This insight can inform targeted support measures, including heritage-sensitive business incentives and incubation of cultural enterprises aligned with local heritage identities;

From a tourism perspective, the framework suggests that visitor spending and economic impact are shaped not only by heritage assets but by the quality of social experiences, physical accessibility, and local economic ecosystems. This supports a shift from volume-driven tourism strategies toward experience-oriented and locally embedded tourism development.

6.3. Research Implications

This study offers significant research implications by directly addressing the conceptual and methodological gaps identified in the literature on heritage economics and heritage-led development. Existing research has largely examined heritage valuation, tourism impacts, infrastructure provision, and local economic outcomes in isolation [

47], resulting in fragmented empirical evidence and limited explanatory coherence. By integrating Heritage Resources, Social By-products, Physical By-products, Economic Backdrop, and Revenue Generation within a single validated framework, this research responds to calls for multidimensional and system-based approaches to analysing heritage economies.

Methodologically, the study demonstrates the suitability of PLS-SEM for modelling complex heritage systems characterized by latent constructs, mediated relationships, and non-linear value creation processes, an area where conventional econometric and impact-assessment models have shown limitations. The combined use of construct operationalization, mediation analysis, and predictive assessment (Q2 and PLSpredict) advances heritage–economy research beyond descriptive or post hoc evaluation toward theory-driven, predictive modelling.

The findings also provide empirical clarification to an unresolved debate in the literature regarding whether heritage assets generate direct economic returns. By establishing that heritage influences revenue generation only through social activation, infrastructural development and economic enabling conditions, the study refines existing theoretical assumptions and offers a more precise explanation of heritage-led value creation mechanisms. The validated framework creates a foundation for comparative, longitudinal, and spatially explicit research on heritage economies. Future studies can extend this model to test contextual variations across different types of heritage towns, governance regimes, and development stages, thereby contributing to cumulative theory building and more robust evidence for heritage planning and policy research.

7. Conclusions

This study developed and empirically validated a Cultural Heritage Economy Model that explains how heritage resources translate into economic outcomes through interconnected social, physical, and economic mechanisms. Drawing on systematic literature synthesis, expert-based construct operationalization, and PLS-SEM analysis, the model integrates Heritage Resources (HR), Social By-products (SB), Physical By-products (PB), and the Economic Backdrop (EB) to explain Revenue Generation (RG).

The results demonstrate that heritage-driven economic value does not arise directly from heritage assets alone. Instead, heritage resources act as upstream enablers that activate social participation, support physical and infrastructural transformation, and strengthen local economic conditions, culminating in revenue outcomes. Importantly, validated sequential structure (HR → SB → PB → EB → RG), and the absence of significant direct effects from heritage resources to economic and revenue outcomes, confirms that heritage-led development is inherently indirect and system-dependent rather than asset-driven and cumulative. The validated model is found to have strong reliability, validity, explanatory power and predictive relevance, as observed in

Section 5.

Beyond economic outcomes, the model contributes to broader discussions on sustainable and resilient urban development. By framing heritage as a catalyst within a socio–physical–economic system, the study aligns heritage planning with principles of sustainability, circular economy, and inclusive growth. Most importantly, the model also supports a circular and regenerative interpretation of heritage-led development, where revenue generated through heritage-related tourism, cultural enterprises, and local economic activity can be strategically reinvested into conservation initiatives, community programmes, and physical infrastructure upgrading. Such reinvestment strengthens the condition and functionality of heritage resources, enhances social engagement, and improves infrastructural capacity, thereby reinforcing the very mechanisms that enable sustained revenue generation. Conversely, neglect of social or infrastructural dimensions may weaken these feedbacks, limiting long-term sustainability.

7.1. Novelty and Original Contribution

This study presents a novel approach towards empirically validated efforts to develop a predictive, system-oriented cultural heritage economy model, with the aid of PLS-SEM. Unlike conventional heritage valuation or tourism impact approaches, the proposed framework integrates social, physical, and economic dimensions within a single explanatory and predictive structure. The novelty lies not only in construct integration but also in demonstrating that heritage-led economic outcomes are inherently mediated and sequential, rather than direct, offering a fundamentally different lens for heritage planning and policy.

7.2. Scope Considerations, Limitations, and Future Directions

While the study makes a substantive methodological and conceptual contribution, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations that also indicate directions for future research. First, the model was validated using expert-driven and pilot-level data, which was appropriate for theory building and model development. However, empirical application at the town or regional scale requires heritage contexts with well-documented, reliable, and disaggregated data across social, physical, and economic dimensions. In many heritage towns, particularly in developing-country contexts, such comprehensive datasets are fragmented, inconsistent, or unavailable, posing practical challenges for large-scale implementation. Future research can extend the framework through town-level applications, leading to direct channelization towards specific policy formations and operational structures. Secondly, as discussed in the measurement model assessment, some constructs exhibited very high reliability values, reflecting strong expert consensus, which affects measurement generalizability but does not compromise internal validity or structural estimation. Further, although Environmental Factors were theoretically relevant, they did not demonstrate sufficient internal consistency for inclusion in the final structural model. This suggests that environmental conditions may operate as broader contextual constraints rather than as directly measurable or moderating mechanisms within the heritage-led economic system examined here. The finding highlights the need for alternative or more granular operationalizations of environmental dimensions, such as carrying capacity thresholds, climate risk exposure, or ecological stress indicators, in future empirical applications.

While

Section 6 focuses on practical and policy implications, future research should build on the present framework to advance empirical, methodological, and theoretical understanding of heritage-led economic systems. Longitudinal studies can extend the model to examine temporal dynamics and feedback processes, such as the reciprocal relationships between revenue generation, conservation investment, and social outcomes. Methodologically, future research may integrate the framework with spatial analysis, scenario modelling, and decision-support tools to better capture place-specific dynamics and planning trade-offs. Further extensions could involve empirical calibration and validation across different spatial scales, from heritage towns to cities and regions, thereby testing the robustness of the sequential mechanisms identified in this study. Such cross-scale and interdisciplinary applications would strengthen the model’s explanatory and predictive utility while enhancing its relevance for evidence-based heritage and urban planning research.

Overall, this study offers a robust, empirically validated framework for understanding cultural heritage economies as integrated socio–spatial–economic systems. By moving beyond isolated heritage valuation and demonstrating the sequential mechanisms through which heritage resources contribute to revenue generation, the research advances both theory and practice in heritage planning and urban development. The proposed model is scalable, adaptable, and predictive-ready, making it suitable for application across diverse heritage contexts, subject to data availability and contextual calibration. Importantly, the framework supports a shift toward more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient approaches to heritage-led urban development, where economic gains reinforce conservation, social well-being, and infrastructural quality. In doing so, the study positions cultural heritage not as a static or extractive resource, but as a dynamic catalyst for long-term socio-economic transformation within sustainable urban systems.