1. Introduction

Globally, climate change is intensifying the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events [

1]. Recent assessments from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warn that climate change-induced disasters such as cyclones and floods are occurring with increased frequency and greater magnitude [

2]. Each time these events occur, they result in enormous human and socio-economic losses. While they can strike anywhere and affect anyone, their adverse consequences are particularly disproportionate and acute in countries with limited adaptive capacities [

3]. Among these impacts, infrastructure systems, including critical assets such as hospitals, housing, transport corridors, and energy grids, are the most vulnerable to destruction and loss [

4]. These disasters disrupt essential services, economic continuity, and livelihoods.

Infrastructure damage and loss due to a climate-induced disaster are particularly acute in developing countries such as India. For instance, urban floods in India have damaged and destroyed several infrastructure systems including roads, bridges, railway and metro lines, houses, and sewage networks [

5]. Empirical evidence shows that Mumbai’s infrastructure is paralysed during the annual monsoons that hit the city [

6]. Similarly, cyclones have affected ports, coastal roads, power transmission, and hospitals in India. Cyclone Tauktae, considered to be a manifestation of climate change [

7], damaged 1576 houses in Maharashtra and caused significant transportation disruptions for several hours [

8].

The infrastructure loss resulting from extreme weather events, as illustrated above, is more significant in India due to the country’s current position at the intersection of rapid development and environmental risk [

9]. Multiple global sources rank India as one of the most disaster-prone and affected countries in the world [

10,

11]. A recent Germanwatch Global Climate Risk Index Report [

12] ranked India as the ninth most extreme-weather-affected country over the last three decades. The same report found that between 1994 and 2024, India witnessed nearly 430 weather events, ranging from deadly heatwaves to monsoons and cyclones, resulting in deaths and billions of USD in economic losses. At the same time, it is predicted that more than 40% of India’s population will live in urban areas by 2030 [

13]. Much of this is expected to happen against the backdrop of climate change-induced extreme weather events.

To meet the demands of urbanisation, economic growth, and the high levels of mobility, India is undertaking large-scale infrastructure development. However, due to India’s growing climate and disaster risks, it is important to build stronger and more climate-resilient infrastructure [

14]. Climate-resilient infrastructure refers to infrastructure that can anticipate, accommodate, and protect against climate and related risks and stressors [

15]. An example of such infrastructure is Copenhagen’s permeable streets, which have the capacity to absorb rain. The Climate Tile, or ‘Klimafisen’ in Danish, was installed in Copenhagen to prevent street flooding; it can also reportedly produce green energy [

16]. Another example is earthquake-resilient buildings designed with seismic-resistant structures and base isolators.

In addition to strengthening physical infrastructure against climate and disaster risks, climate-resilient infrastructure development must also account for the safety and inclusivity of users [

17]. For example, large-scale road infrastructure projects, while essential for economic growth and mobility, can exacerbate safety risks for non-motorised users if road-safety considerations are not adequately integrated at the planning and design stage. Previous research has highlighted the significance of incorporating cyclist safety and spatial risk assessments into infrastructure planning, for example, road-incident mapping and data-driven analysis [

18]. Integrating such road-safety considerations within climate-resilient infrastructure planning is thus essential to ensuring that infrastructure development is climate-adaptive, socially inclusive, and aligned with broader public safety objectives.

Recent climate-related infrastructure failures and disruptions in India (such as the significant infrastructure damage following the 2025 floods and landslides in Dharali, Himachal Pradesh [

19], and the 2024 Wayanad landslides in Kerala [

20]) highlight the urgency of ensuring that infrastructure is planned, designed, constructed, and maintained with climate risks in mind [

21]. If India is to truly strengthen its resilience to climate-induced risks including natural disasters, the development and implementation of climate-resilient infrastructure must become an immediate, national priority [

22] in law, policy, and implementation.

1.1. Study Rationale

Recent analysis by the World Bank reinforces the urgent need to build climate-resilient infrastructure in India [

23]. The World Bank projects that India needs to invest over USD 2.4 trillion by 2050 to build climate-resilient urban infrastructure as its rapidly expanding cities face growing challenges from events linked to climate change. Climate-resilient infrastructure can reduce direct and indirect losses due to extreme weather events, safeguard livelihoods, and support the continuity of essential services during disasters [

24]. Despite this urgency, systematic legal and policy analyses of India’s climate-resilient infrastructure remain limited [

25]. There is limited research on how the legislative and regulatory frameworks in India can promote the integration of climate risk considerations into the country’s infrastructure development.

As international legal developments adopt preventive-risk-based approaches to reduce the impact from climate-induced events, it becomes important to evaluate how the Indian legal framework performs in this context. This is crucial since India is a signatory to several international agreements on this subject such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (Sendai Framework) [

26] and the Paris Agreement on Climate Change 2016 (Paris Agreement) [

27].

Furthermore, a very recent report from the National Institute for Transforming India (NITI Aayog) observed that India lacks systematic consideration and integration of climate resilience and risks in its infrastructure planning and policy initiatives [

28]. Additionally, it was also reported that while Indian infrastructure is increasingly integrating climate thinking, significant gaps and uneven coverage continue to hinder a complete integration [

29]. Thus, in this study, in addition to international legal standards, best practices from Japan were also used to evaluate where the Japanese and Indian frameworks align or differ. This facilitated a more informed evaluation of the Indian framework.

The increasing threat from climate-induced weather events and their consequent infrastructure loss warrant an analysis of the Indian legal framework to identify the strengths, gaps, and opportunities for centre-staging climate resilience in infrastructure planning and governance in India.

1.2. Aims of the Study

The main aim of this study was to analyse the legal and policy trajectories that have shaped and continue to shape climate-resilient infrastructure in India. The study addresses the relative paucity of legal and policy research on climate-resilient infrastructure in India by examining how climate risk considerations are incorporated into the Indian legislative framework and evaluating their efficacy against established international standards and select best practices that were identified through a comparison with the framework in Japan. Consequently, the study contributes to our understanding of a pressing issue, and the findings could have ramifications for climate change strategies, resilience, and sustainable development in other climate-vulnerable regions.

1.3. Research Questions

This study was guided by a core set of research questions aimed at evaluating the efficacy of the legal and policy dimensions of climate-resilient infrastructure in India. First, does the existing Indian legal framework integrate climate risk considerations into infrastructure planning and development? Second, how adequate are these frameworks when compared to established international standards and best practices? Lastly, what impact do the extant provisions have in practice, and what constraints hinder their implementation?

To address these questions, the study used an analytical, comparative, and evaluative lens to critically assess the effectiveness of the climate-resilient infrastructure framework in India. Thus, this study contributes to an urgent global issue and will likely have valuable lessons for developing countries and regions sitting at the crossroads of climate-related risks and development goals.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the materials and methods while

Section 3 outlines the conceptual and analytical frameworks that form the foundation for climate-resilient infrastructure governance.

Section 4 discusses India’s climate risk and infrastructure environment.

Section 5 provides a critical examination of India’s legislative and policy frameworks that govern climate-resilient infrastructure while

Section 6 describes the case studies of the Mumbai Coastal Road and Chandigarh–Manali Highway projects that were used to assess the on-the-ground operationalisation of the legislative and policy frameworks in India.

Section 7 and

Section 8 present the results and discussion, respectively, while the conclusions are detailed in

Section 9.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a qualitative and comparative analysis approach to examine and evaluate the efficacy of India’s legal and policy landscape in integrating climate resilience into its infrastructure planning and development sector. An analytical, comparative, and evaluative research design was adopted. Established principles in public international law and best practices from Japan were identified and compared to the Indian framework. Japan is one of the most affected countries from natural disasters [

30], yet it is a global leader in disaster risk governance through mainstreaming of risk strategies into its infrastructure sector [

31], among other policies, making it a suitable comparator for the present study.

The analysis draws on doctrinal primary and secondary data sources including primary legal and policy instruments, regulatory guidelines and policies, and judicial decisions. International legal instruments and relevant reports from international agencies, research papers, and newspaper articles were also reviewed.

Additionally, case studies on the Mumbai Coastal Road and Chandigarh–Manali Highway projects were also performed to illustrate how climate-resilient infrastructural considerations operate in practice in India and to contextualise the policy landscape with real-world situations. These case studies were selected using a purposive sampling approach [

32] based on multiple criteria. First, they are representative of large-scale, climate-exposed infrastructure projects [

33] in India that are critical to the country’s economic development and service delivery. This allowed for an assessment of how mainstream climate risk considerations are integrated into infrastructure governance in India.

Second, the selected projects are exposed to distinct and contrasting climate risks, including coastal flooding, sea level rise, landslides, and extreme rainfall [

34,

35]. This enabled an evaluation of how different hazard profiles are addressed within the existing legal and policy framework. Third, the projects are also geographically diverse and are situated in different ecological contexts in India, enabling a diverse analysis of the operation of the framework.

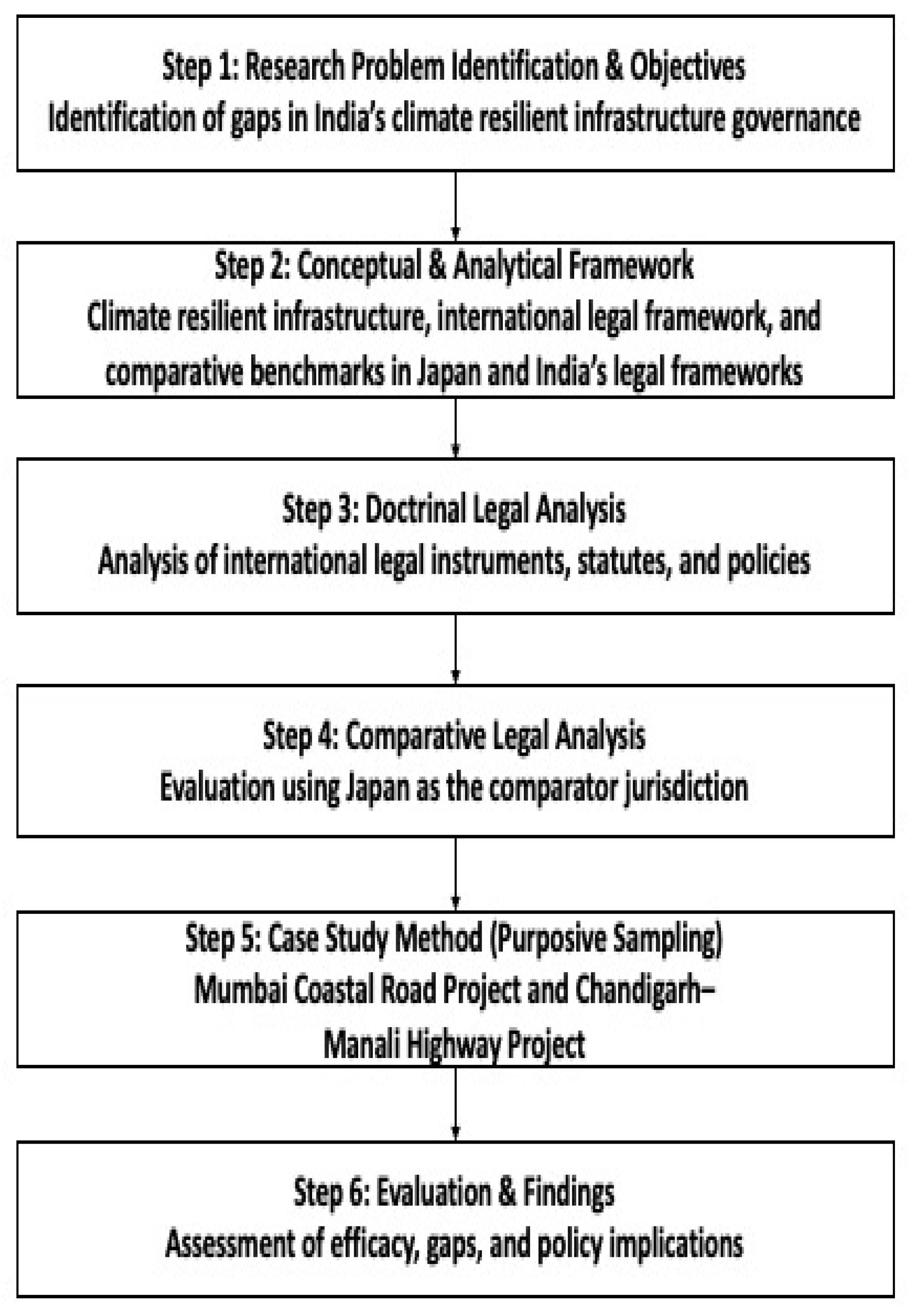

Figure 1 below presents the step-by-step research methodology used in the present study. The research design proceeds from the identification of the research problem to the development of a conceptual framework, to doctrinal and comparative legal analyses, followed by selected case studies.

Collectively, this methodology enhanced the analytical depth of the case studies (delineated in

Section 6) and support broader inferences regarding the operationalisation of climate-resilient infrastructure laws and policies in India. Altogether, the approaches used in this study enabled a comprehensive understanding of the strengths, gaps, and trajectory of climate resilience integration in India’s infrastructure sector.

3. Conceptual and Analytical Frameworks

Climate-resilient infrastructure is grounded in the broader frameworks of climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and resilience planning and development [

36]. These frameworks recognise infrastructure systems as critical enablers of socio-economic stability and service continuity while simultaneously acknowledging their heightened exposure to climate-induced hazards [

37]. Consequently, climate resilience in infrastructure is not restricted to structural robustness but also extends to the capacity of systems to anticipate, absorb, adapt to, and recover from climate-related shocks over their life cycle [

37].

In addition to “climate resilience” and “climate-resilient infrastructure”, this paper also uses the term “risk-informed infrastructure”. While these terms convey different meanings, they are intricately related to each other. Climate resilience refers to the capacity of systems to anticipate, absorb, and recover from climate-induced shocks, while climate-resilient infrastructure refers to infrastructure systems possessing this capacity [

38]. In this study, climate-resilient infrastructure is an outcome-oriented concept that operationalises climate resilience through risk-informed planning, ecosystem-based approaches, and adaptive governance in infrastructure development.

This section outlines the conceptual foundations and analytical framework that informed the analysis of the efficacy of the Indian legal and policy framework in integrating climate risk mitigation strategies into the infrastructure sector. The conceptual framework was informed by the standards for disaster risk governance, resilience, and adaptive climate governance from international policy instruments [

26] and contemporary scholarship on the subject [

39]. These approaches emphasise anticipatory risk reduction, integration of climate considerations into development planning, and the role of legal and institutional frameworks in enhancing resilience [

40].

Taken together, these approaches operate as analytical lenses through which the study evaluated the extent to which the legal and policy instruments operationalise climate resilience in the infrastructure planning, implementation, operation, and maintenance stages.

Figure 2 below describes the thematic areas of conceptual and analytical frameworks used in the present study.

Figure 2 broadly outlines the key concepts that were analysed in this study: (i) climate-resilient infrastructure, (ii) international legal frameworks that integrate climate risk into infrastructure planning, (iii) best practices from the frameworks in Japan, and (iv) an evaluation of the Indian legal and policy framework.

3.1. Climate-Resilient Infrastructure

Resilience has, in many ways, become a “buzzword” in the discourse on climate change-induced extreme weather events and disasters. However, it is important to ensure that the word does not lose its meaning [

41]. Coined by Buzz Holding, resilience refers to the ability of ecosystems to recover after shocks [

42]. In this context, climate-resilient infrastructure refers to infrastructure that is planned, designed, constructed, and maintained with climate change impacts in mind. Resilient infrastructure systems must not only anticipate and withstand climate change stresses but should also be able to recover from them [

43].

Achieving resilience therefore requires moving beyond reliance on conventional physical infrastructure and towards the systematic integration of green infrastructure (such as mangroves and wetlands) into built/physical environments. While physical infrastructure such as energy systems, transport networks, and drainage systems is critical for economic development service delivery, green or ecosystem-based infrastructure plays a complementary role by acting as natural buffers against extreme weather events.

Therefore, from a legal and governance perspective, climate-resilient infrastructure requires regulatory frameworks that mandate climate risk-informed planning, integrate ecosystem-based approaches, and ensure enforceable standards across the infrastructure life cycle—from planning, siting, and design to operation and maintenance [

26]. The absence of such legally embedded risk considerations often results in infrastructure that is unable to withstand the test of climate-induced threats.

3.2. International Frameworks for Climate and Natural Disaster Risks to Infrastructure

To systematically evaluate India’s policy trends, this study employed an analytical framework based on established principles of climate-resilient infrastructure governance under public international law for managing climate risks including natural disaster risks. These include the Sendai Framework [

26], the Paris Agreement, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2015–2030 (SDGs) [

44].

The Sendai Framework contains several provisions that govern the integration of climate risk into infrastructure. Priority 4, for instance, calls for measures to enhance disaster preparedness for effective responses and to “build back better” during recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. At the national and local levels, nations are called upon to “promote the resilience of new and existing critical infrastructure, including water, transportation and telecommunications infrastructure, educational facilities, hospitals and other health facilities, to ensure they remain safe, effective and operational during and after disasters in order to provide live-saving and essential services”. Another measure calls for relocation of critical infrastructure to areas outside of the high-risk region.

Likewise, SDG 9 calls upon nations to develop “quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all”. Furthermore, SDGs 11 and 13 concern smart cities and climate action. SDG 11 specifically calls for sustainable cities and communities through building cities and communities resilient to disasters, which is in alignment with the provisions in the Sendai Framework. Together, these frameworks encourage mainstreaming of climate risk considerations in the infrastructure sector. However, it is pertinent to note that these international law provisions for climate risk and resilient infrastructure are soft laws and are non-binding. Despite this limitation, the literature shows that soft laws can play a critical role in guiding state conduct [

45].

In this study, India’s legal policy framework was benchmarked against international frameworks using indicators such as risk prevention, resilience of critical infrastructure, and integration of climate considerations into developmental planning. This enabled the researchers to not only analyse the framework in India but also evaluate its efficacy compared with established international standards in a meaningful and informed way.

3.3. Comparative Benchmarks in Japan

Japan is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world. At the same time, Japan is considered to be a world leader in the management of disasters. Given the advanced disaster management systems and approaches in Japan [

46], this study identified the best legal practices for the integration of climate resilience into the infrastructure sector in Japan. These best practices were used as comparative benchmarks against which the Indian legal framework was evaluated. Japan’s Climate Change Adaptation Act of 2018 promoted adaptation, development of information infrastructure, and resilience [

47]. Other laws such as the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act 1961 [

48], and the Basic Act for National Resilience 2018 [

49], also address climate-resilient infrastructure. After the Climate Change Adaptation Act, the Climate Change Action Plan 2021, was notified [

50].

This study examined Japan’s legal framework using several parameters, including legal enforceability of provisions on green infrastructure, institutional coordination mechanisms, integration of climate risk into infrastructure planning, and use of ecosystem-based approaches. These parameters were subsequently adopted to analyse the Indian legal and policy framework and in the case studies.

3.4. India’s Legal and Policy Framework on Climate-Resilient Infrastructure

India’s legal and policy landscape frames climate-resilient infrastructure through key provisions:

- (a)

The Disaster Management Act, 2005 [

51], was proposed to manage disasters. It was recently amended through the Disaster Management (Amendment) Act, 2025 [

52];

- (b)

The National Action Plan on Climate Change 2008 (NAPCC) [

53], emphasises climate-resilient infrastructure through specific missions;

- (c)

The National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP), the PM Gati Shakti Mission’s National Master Plan for World Class Modern Infrastructure [

54], and Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) aim to promote the integration of resilience and sustainability criteria into planning and development [

55].

Together, these provisions outline the legal and policy trajectories for integrating climate-resilient considerations into the infrastructure sector in India. However, their effectiveness ultimately depends on the extent to which climate considerations are legally mandated, institutionally coordinated, and operationalised across sectors and levels of governance [

56].

The above conceptual and analytical framework guided the examination and evaluation of India’s legal and policy instruments and the selected infrastructure case studies, enabling a structured assessment of the extent to which climate resilience is embedded in law, policy, and practice.

4. India’s Climate Risk and Infrastructure Environment

Currently, India stands at a critical juncture between economic development and intensifying climate and disaster risks. As one of the fastest growing economies in the world [

57], India is experiencing large-scale urbanisation, infrastructure expansion, and land-use changes. Simultaneously, it ranks among the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries [

58]. Recurring extreme weather events in India have collectively caused thousands of fatalities and multi-billion-dollar economic losses annually. Infrastructural loss due to climate risk is acute, and more is anticipated in the future.

Table 1 lists the disaster-induced losses in India in recent decades.

As shown in

Table 1 [

59], climate-and weather-related disasters in India have resulted in escalating human, economic, and infrastructural losses, highlighting the increasing vulnerability of infrastructure systems to climate risks.

4.1. Intensifying Climate Hazards and Infrastructural Impact

India’s climate hazards have intensified in frequency, scale and unpredictability due to global warming and climatic shifts. For instance, urban floods along the eastern and western coasts have increased in intensity, damaging power grids, transport corridors, and coastal infrastructure. Heatwaves have become longer and deadlier, with temperatures often exceeding 48 °C, stressing transport systems, energy grids, and urban water infrastructure [

60]. Sea-level rise and coastal erosion threaten India’s coastal cities and ports, desalination plants, and coastal protection structures [

61]. Consequently, and collectively, these hazards expose the vulnerability of India’s existing infrastructure, much of which was not designed for climate-related shocks and stresses. These disruptions and damages show that infrastructure vulnerability in India is shaped not only by increasing climate change-related disasters, but also by historical design, regulatory gaps, and limited consideration of climate risk in infrastructure planning frameworks.

4.2. Infrastructure Deficits and Vulnerabilities

Infrastructure systems in India face structural and systematic challenges that amplify their climate risks. Examples of these deficits and vulnerabilities in “legacy infrastructure” [

62] include the following:

- (a)

Ageing and overburdened assets such as railways and dams whose designs did not originally factor in climate-induced extreme weather risks;

- (b)

Rapid urbanisation and loss of green cover (such as forests), which have increased the risk of climate shocks and disasters [

63];

- (c)

Location of critical infrastructure such as industrial facilities and energy installations in high-risk cyclone or seismic zones [

64];

- (d)

Fragmented institutional and regulatory capacities since infrastructure governance in India remains fragmented across central, state, and municipal authorities with overlapping mandates [

65].

Taken together, these structural deficits reveal that the climate risk to infrastructure in India is compounded by governance fragmentation and the absence of legally binding, risk-informed planning obligations across infrastructure sectors.

4.3. Widening Infrastructure Gap Under Climate Stress

India’s estimated infrastructure investment requirements are projected to exceed USD 4.5 trillion by 2040 [

66]. Climate change is expected to widen this gap by increasing repair costs, disrupting essential services, and accelerating asset depreciation [

67]. Not only will new infrastructure be needed, but even the existing infrastructure will require repair and maintenance. For example, flood-prone highways require continual reinforcement to ensure they can withstand floods.

The factors identified above and recent real-world experiences demonstrate the need for India to shift from its reactive approach to managing infrastructure losses from climate-induced disasters to an approach that focuses on proactive risk mitigation. This transition will require integrating hazard and vulnerability assessments into infrastructure approval processes, mainstreaming nature-based solutions, and adopting resilient design standards. Climate-resilient infrastructure in India no longer remains an optional development priority and needs to be treated as a legal and policy necessity—one that is closely linked to public safety, economic growth, and long-term sustainability.

These conditions underscore the need to examine whether India’s legal and policy framework effectively embeds climate risk considerations into infrastructure governance; this assessment was undertaken using the analytical benchmarks identified in

Section 3 and is detailed in the subsequent sections.

5. Climate-Resilient Infrastructure: Legal Policy Framework in India

While there is no single comprehensive instrument in India that addresses, regulates, and governs climate-resilient infrastructure, the approach to climate-resilient infrastructure has evolved over the past two decades from a reactive to a more integrated, risk-based development paradigm. As vulnerabilities remain high, India has been progressively including considerations of climate and related risks in its national policies, sectoral missions, and urban development programmes [

68]. The overarching policy direction reflects a recognition that resilient infrastructure is essential not only to safeguard lives and livelihoods but also to sustain long-term economic growth in a climate-volatile environment.

Presented below is an analysis of the key legal and policy instruments that integrate climate resilience into infrastructure planning and development in India. This section evaluates these instruments against the analytical benchmarks identified in

Section 3 regarding risk prevention, institutional coordination, integration of climate considerations, and ecosystem-based approaches in infrastructure planning.

5.1. The Disaster Management Act, 2005 (As Amended) and Guidelines

The Disaster Management Act, 2005 is India’s principal law on managing disasters. Although the law does not contain a mandate on climate-resilient infrastructure, several provisions indirectly address the climate resilience of India’s infrastructure. Section 11(3) of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 mandates that the National Plan on Disaster Management includes mitigation measures in all development plans and projects and disaster management plans at the state and district levels. Accordingly, the National Disaster Management Plan 2016 (which was updated in 2019 and 2020), specifically calls for climate risk-informed infrastructure planning, resilient construction standards, and resilient lifeline infrastructure. Although not legislated separately, these provisions flow from the powers of disaster management authorities established under the law.

Furthermore, in accordance with the Disaster Management Act 2005, there are several guidelines addressing risk and resilience in infrastructure. These include the (i) Guidelines for Urban Flood Management (2010) [

69], (ii) National Landslide Risk Management Strategy (2019) [

70], and (iii) Simplified Guidelines for Earthquake Safety of Buildings from the National Building Code of India 2016 (NBC 2016) [

71]. The Guidelines for Urban Flood Management 2010 specifically include provisions on creating durable public assets and enhancing public–private partnerships in the infrastructure sector. Special design considerations are provided for critical infrastructure such as airports and roads. The National Landslide Risk Management Strategy 2019 specifically calls for amendments of building and town planning laws to address the need to preserve ecological balance in and around hill towns in India. The primary intent of the NBC 2016 is to prevent the collapse of structures and protect human and animal lives. The Simplified Guidelines for Earthquake Safety of Buildings from NBC 2016 lays down strategies that can be used to integrate earthquake safety measures for buildings and other infrastructure. Each of the guidelines and strategies mentioned above lay down technical standards for building sustainable and resilient roads, bridges, public buildings, and coastal defences.

Despite these provisions, the contribution of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 and its guidelines for climate-resilient infrastructure remain limited. The absence of explicit infrastructure-specific statutory obligations, the over-reliance on non-binding guidelines, and the uneven implementation across Indian states hinder effective embedding of climate resilience into infrastructure governance.

5.2. NAPCC

Launched in 2008, the NAPCC established a strategic vision for climate adaptation and mitigation across national sectors in India [

72]. It incorporates climate-resilient infrastructure through its missions. These include strategies for adapting to climate risks and building resilient infrastructure in areas such as urban development and sustainable habitats. Some of its key missions and their brief features that are pertinent to climate-resilient infrastructure are presented in

Table 2 below.

Additionally, many Indian states have developed their own State Action Plans on Climate Change. These plans outline sector-specific and cross-sectoral actions that include adaptation and climate-resilient infrastructure planning based on their own unique challenges. Although the NAPCC provides important strategic direction, its mission-based and policy-oriented structure lacks binding legal force. Consequently, this results in an uneven incorporation of climate-resilient objectives across sectors and states.

5.3. Sector-Specific Infrastructure Policies Supporting Climate Resilience

Several sector-specific urban missions also incorporate climate-resilience components. For instance, AMRUT (launched in 2015) focuses on establishing infrastructure that ensures adequate sewerage networks and water supply for urban transformation by implementing urban revival projects. Its enhanced version is referred to as AMRUT 2.0 (Water Secure Cities), which was launched in 2021. Although AMRUT 2.0 does not explicitly address climate-resilient infrastructure, its focus on basic urban infrastructure indirectly benefits climate-resilient infrastructure [

55]. Further, its emphasis on stormwater drainage and flood mitigation and promoting climate sensitive urban design are essential for integrating climate resilience into infrastructure.

Additionally, to address sea level rise and coastal hazards, Integrated Coastal Zone Management was developed as a coordinating and hazard sensitive planning process [

76]. The Coastal Regulation Zone Notification 2019 restricts unsafe construction and protects ecological buffers [

77]. The National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project has established cyclone shelters, resilient roads, embankments, and early warning systems [

78]. Launched in 2019, the NIP was set up to invest USD 1.5 billion across critical sectors such as energy, transport, water, and urban development between 2020 and 2025 [

79].

Despite the progress and achievements made above, certain significant gaps remain. These include (1) fragmented governance across ministries, which impairs coordination; (2) lack of uniform enforcement; (3) insufficient local level capacity; (4) insufficient maintenance budgets; and (5) data scarcity on climate stress impacts at micro-levels. India’s overall climate-resilient infrastructure policy landscape is comprehensive but uneven in implementations. The framework combines (1) a patchwork of guidelines that are non-binding, (2) disaster risk legislation, (3) climate commitments, and (4) sectoral missions. However, for climate resilience to be fully embedded, India needs stronger enforcement mechanisms, decentralised capacities, nature-based solutions, and mandatory climate-risk assessments for all future public infrastructure projects.

Unlike jurisdictions such as Japan, where climate-resilient infrastructure is a legal requirement backed by strong institutional frameworks and ecosystem-based approaches, India’s approach remains predominantly policy driven, with limited legal enforcement and uneven implementation.

6. Case Studies: Operationalising India’s Climate-Resilient Infrastructure in Practice

To examine and evaluate how the legal and policy framework on climate-resilient infrastructure operates in the real world, two projects were selected as case studies through purposive sampling: (i) the Mumbai Coastal Road Project; and (ii) the Chandigarh–Manali Highway Project. These case studies were used to assess whether the legal and policy instruments analysed in

Section 5, particularly those related to climate risk integration, ecosystem protection, and institutional accountability, are effectively operationalised at the project level.

The Mumbai Coastal Road Project represents a large-scale urban infrastructure project situated within a high-risk, climate-vulnerable environment. Located in India’s densely populated and ecologically sensitive coastal city of Mumbai [

80], the project has been under intense judicial scrutiny and public contestation due to its claims of being climate resilient. This has consequently made the project an ideal case for evaluating the implementation of India’s legal framework.

In contrast to Mumbai’s coastal climatic risks, the Chandigarh–Manali Highway Project presents mountainous and Himalayan climate risks. Given its location in the ecologically fragile Himalayan region that has witnessed multiple natural disasters and is facing increasing climate risks [

81], the project presents a valuable case for assessing whether risk-informed planning is being implemented.

Together, these case studies serve as empirical tests for assessing the enforceability and implementation capacity of India’s climate-resilient infrastructure governance framework.

6.1. Case Study 1: The Mumbai Coastal Road Project

Once a thriving ecosystem of dense mangroves, Mumbai’s coastline has now been concreted into oblivion due to land reclamation and infrastructural development [

82]. The Mumbai Coastal Road Project, which involves the construction of a 29.2 km coastal transport corridor, is one such example of this extensive urban development. The project has been positioned as a climate resilience project by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation [

83], which is the official governmental authority responsible for the project, and is aimed at decongesting and improving mobility in Mumbai.

However, despite the claims of incorporating climate-resilient infrastructure and following ecosystem protection practices, the project has triggered criticisms over several environmental challenges, becoming a landmark case in India’s debate on climate-sensitive infrastructure [

84]. While addressing these criticisms, the Additional Municipal Commissioner of the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (the developer of the project) observed that about 13.6% of the project area had been earmarked for the construction of safety walls to protect the project against sea waves. Another measure was the translocation of two colonies of corals that were found during the construction of the project [

83].

Moreover, publicly available information shows that the project integrates other climate-resilient components in its approved design, such as sea-wall engineering designed for 100-year storm surge scenarios, rock revetments and tetrapod for coastal protection against higher energy waves, and inter-tidal protection measures and escape tunnels. However, critics and scientific studies have highlighted risks in the form of potential alteration of natural tidal flows, increased vulnerability of adjacent fishing communities, and loss of intertidal habitats [

84]. These are reportedly likely to increase flood risks within the vicinity of the coastal road.

The Mumbai Coastal Road Project underwent judicial scrutiny for adherence to coastal regulation zone standards, environment impact assessment compliance, and mangrove protection orders. However, the Supreme Court of India refused to stall its development and modified its own order and allowed the project to continue [

85]. The Court balanced infrastructure needs against environmental safeguards, directing the project to minimise reclamation, monitor the coastal ecology, continue to protect mangrove buffer zones, and ensure that project execution follows regulatory standards.

Beyond judicial scrutiny, the project was marred by seepage issues shortly after it opened to the public in 2024 and two weeks before monsoons arrived [

86]. While the authorities called the seepages “routine”, the leakages made many question the claims of its disaster-proof and climate-resilience capabilities. In fact, in 2022, the project was called “maladaptive” by the IPCC [

87] and projections indicate increased climate risks to the project and the city [

34].

Thus, the Mumbai Coastal Road Project highlights the limitations of the existing legal framework for climate-resilient infrastructure. This case illustrates how climate resilience is often treated as a project-specific technical consideration rather than as a legally enforceable governance requirement. The absence of independent audits to check the credibility of assertions made by the developers is a serious issue. This oversight shows how even the judiciary can come to different conclusions on the development vs. environment debate [

88].

6.2. Case Study 2: Chandigarh–Manali Highway

The Chandigarh–Manali Highway is one of north India’s most important transport corridors, connecting the states of Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh.

This highway traverses some of the most climate-sensitive and geologically fragile terrains, thus making it a relevant case study for analysing climate-resilient infrastructure in India. The 197 km long highway, a lifeline for the Himalayan region (extending up to Ladakh), is frequently blocked by landslides, particularly between Kullu and Mandi [

89], which results in death, damage, and transportation disruptions [

90].

In recent times, frequent closure of the highway due to landslides has been reported. This has put the spotlight on the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) for using unscientific methods for road building and turning it into a dangerous highway. Directives were subsequently issued to perform repair work on the highway, cutting off access to key areas in the ecologically fragile state. In its Sustainability Report for 2023–2024, the NHAI notes that “it is exploring ways to make highway infrastructure more climate resilient…” [

91]. These policy-level commitments have not translated into consistent on-the-ground realities, evidenced by the recurrent landslides, repeated closures, and continued infrastructure failure along the corridor.

The corridor remains vulnerable to climate change-induced natural disasters and extreme weather events. The literature has identified several factors: unsustainable construction practices, maintenance deficits, and insufficient integration of climate risk into legal and planning frameworks. In fact, the situation in the State of Himachal Pradesh has been so dire that the Supreme Court of India has called on the Government of India to take immediate measures to stop unsustainable practices, particularly developmental practices [

92].

This project is an important subject for a case study since the State of Himachal Pradesh is an inherently disaster-prone and ecologically sensitive in the country. Recurring disasters and the resulting destruction cause the loss of human lives and infrastructural damage. These case studies show that while efforts are being made, gaps remain. Chief amongst these is the absence of a binding legal institutional framework in India requiring comprehensive climate risk assessments, ecosystem sensitive-design standards, and enforceable monitoring for infrastructure projects.

These cases reveal the absence of mandatory climate risk assessments at the approval stage, weak enforcement of environmentally sensitive design standards, and fragmented institutional responsibility across transport, environment, and disaster management authorities. Presented below in

Table 3 is a summary of the case studied undertaken in the present paper.

Cumulatively, these case studies demonstrate that although climate resilience is increasingly being referenced within India’s legal and policy discussions, it remains weakly integrated within enforceable frameworks, leading to continued infrastructure vulnerability due to inconsistent implementation. At the same time, unsustainable infrastructure planning, without scientific studies and independent environmental audits, amplifies the risks of climate-related disasters.

7. Results

The present study was conducted to evaluate the Indian legal framework on climate-resilient infrastructure in an international context. The analysis of India’s climate-resilient infrastructure legal and policy framework, supported by the case studies of the Mumbai Coastal Road and Chandigarh–Manali Highway projects, reveals that India has begun to incrementally integrate climate-risk considerations into its infrastructure governance framework. When viewed through the analytical lens of disaster risk governance, including risk reduction, improving resilience, and climate adaptation in an international context, and compared with the best practices in Japan, these developments reflect a gradual shift from purely growth-oriented infrastructure planning towards a more-risk informed and resilience-oriented development paradigm.

Several key findings emerged from the study:

- (i)

Climate resilience principles are being increasingly embedded into India’s institutional frameworks through the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (as amended), the NDM Guidelines, and sector-specific climate missions. While the statute does not specifically mandate climate-resilient infrastructure, its guidelines and climate missions do contain references to it. Though non-binding, they provide important policy entry points and standards for integrating climate risk reduction into development projects.

- (ii)

The case studies showed that urban and large-scale infrastructure projects are progressively incorporating ecosystem- and nature-based approaches to meet the increasing resilience demands. Measures such as sea-wall engineering, the use of tetrapod, and slope stabilisation through vegetation demonstrate the increased integration of green infrastructure to enhance resilience. However, the adoption of such approaches remains project-specific and discretionary rather than mandatory through legal provisions.

- (iii)

The judiciary is playing an important role in ensuring ecological safeguards and climate concerns are being considered in major infrastructure projects, though in an ad hoc and project-specific manner. The judiciary presently functions as a corrective mechanism and resilience provisions have yet to be incorporated into the governance framework.

- (iv)

Central and state governments have adopted hybrid resilience strategies that combine engineering solutions and restoration of ecological buffers. However, the effectiveness of the combination of physical and green infrastructure in India is constrained. This is largely due to the lack of binding provisions and the absence of enforceable legal obligations that mandate resilience planning in the infrastructure sector.

Despite these positive trends, the study also highlights persistent challenges such as fragmented governance, a lack of binding obligations, inadequate mechanisms for systematic climate-risk screening at the project approval stage, and a lack of transparency.

8. Discussion

When evaluated against the conceptual and analytical framework used in this study, the Indian framework shows increasing alignment with the established standards. The Indian approach to climate-resilient infrastructure reflects a transition in governance where the importance of climate resilience is being increasingly recognised, but it has not yet been fully integrated into the legal and policy framework.

As one of the fastest growing economies in the world, there are many lessons that India must learn. This study’s findings on its legal and policy landscape for risk-based infrastructure development broadly align with the existing literature on disaster risk governance and climate adaptation, which has highlighted the limitations of policy-driven resilience approaches in the absence of legally binding mandates. While recognition of resilience in policy is increasing, implementation remains uneven due to institutional fragmentation and weak enforcement.

Japan’s legal framework for disaster management and climate adaptation is characterised by clear statutory mandates. Some of these include mandatory risk assessments, legally integrated land-use planning, dedicated adaptation legislation, and integrated planning mechanisms that explicitly address infrastructure resilience. These enforceable statutory provisions ensure that climate risk mitigation is not merely discretionary in nature and is systematically embedded into the country’s infrastructure planning and development process. In contrast, India’s approach remains largely policy-driven and indirect, with limited binding obligations for climate-resilient infrastructure. Adapting selected elements of Japan’s framework—particularly those on mandatory climate risk assessment—could offer viable pathways for strengthening India’s infrastructure governance through modification of existing policy instruments such as the Disaster Management Act, 2005. Specific binding legal provisions could ensure that disaster management authorities incorporate climate risk considerations into the infrastructure sector in India.

From an operational perspective, strengthening enforceability within India’s climate-resilient infrastructure framework would require incremental legal and regulatory interventions rather than a comprehensive legislative overhaul. First, binding climate and disaster risk assessment obligations could be introduced through targeted amendments to existing statutes such as the Disaster Management Act, 2005. Second, climate-risk screening requirements could be systematically integrated into environmental clearance and project approval processes, ensuring that resilience considerations are not merely left as post-climate-related-disaster obligations. Third, enforceability could be enhanced by requiring compliance with resilience standards for project approvals, funding disbursements, and monitoring mechanisms. Such measures would enable a transition from predominantly policy-driven resilience frameworks to enforceable, risk-informed infrastructure governance.

9. Conclusions

India’s climate-resilient infrastructure landscape reflects both significant progress and enduring vulnerabilities. As climate extremes intensify, manifesting as recurrent urban floods, severe cyclones, heatwaves, and coastal erosion, the need to embed resilience into every stage of infrastructure planning and development has become not only a development priority but also a legal and governance imperative. This study demonstrates that India possesses a wide-ranging policy architecture capable of supporting climate-resilient development, but the effectiveness of this system hinges on execution at the state, municipal, and project levels. These conclusions were derived from a doctrinal analysis of the Indian legal and policy framework, as well as the empirical insights drawn from the Mumbai Coastal Road Project and Chandigarh–Manali Highway Project case studies.

It is pertinent to note that while India possesses an extensive and evolving policy architecture that acknowledges the importance of climate resilience, these considerations remain largely non-binding and unevenly operationalised across infrastructure sectors and governance levels. Furthermore, climate risk integration into infrastructure planning in India is predominantly policy-driven rather than legally mandated, resulting in inconsistent application at the state, municipal, and project levels.

The case studies also illustrate the complex and often contested balance between infrastructure expansion, regulatory compliance, and environmental sustainability. Projects like the Mumbai Coastal Road and the Chandigarh–Manali Highway reveal the limitations associated with fragmented governance systems and highlight the need for stronger climate change laws that require developers and authorities to integrate resilience at all stages of the infrastructure development process. These limitations are primarily attributable to the absence of enforceable statutes mandating climate-risk integration and ecosystem-sensitive design within infrastructure planning and approval processes.

Moving forward, India’s resilience strategy must adopt a multi-dimensional and legally embedded approach. This study’s findings suggest that best practices can be drawn from the legal framework in Japan, which includes enforceable legal provisions on climate-resilient infrastructure; this is not the case in the extant framework in India. Improvements to the Indian framework should include (i) enforcement of risk-informed standards across sectors; (ii) strengthening of institutional coordination between planners, environmental authorities, and disaster management agencies; (iii) scaling up nature-based solutions alongside engineered defences; and (iv) ensuring transparent, participatory decision-making for major infrastructure projects.

Future research should examine the efficacy of emerging climate-risk screening tools, fiscal mechanisms, and monitoring frameworks at sub-national levels, and assess how legally binding resilience standards influence long-term infrastructure performance. Comparisons of jurisdictions with differing legal traditions could further identify potential pathways for translating resilience commitments into enforceable governance outcomes.

If pursued systematically, these measures could enable India to transition from reactive disaster responses to proactive, climate-proofed development pathways, allowing India to safeguard its critical infrastructure and urban systems. Implementing these measures could also provide directions for climate-resilient growth in other developing economies facing similar challenges.