Hydroponic Nature-Based Wastewater Treatment: Changes in Algal Communities and the Limitations of Laser Granulometry for Taxonomic Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

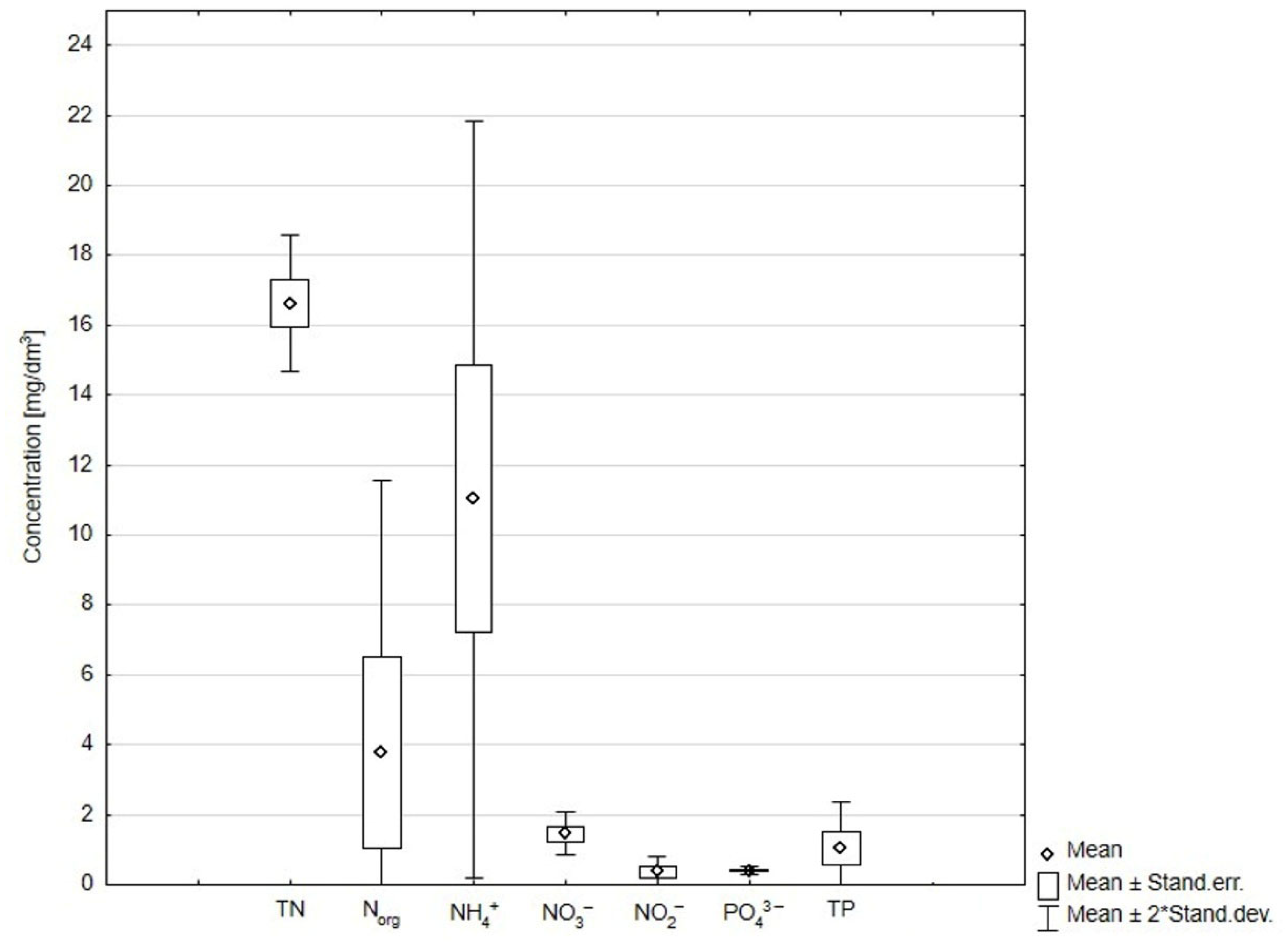

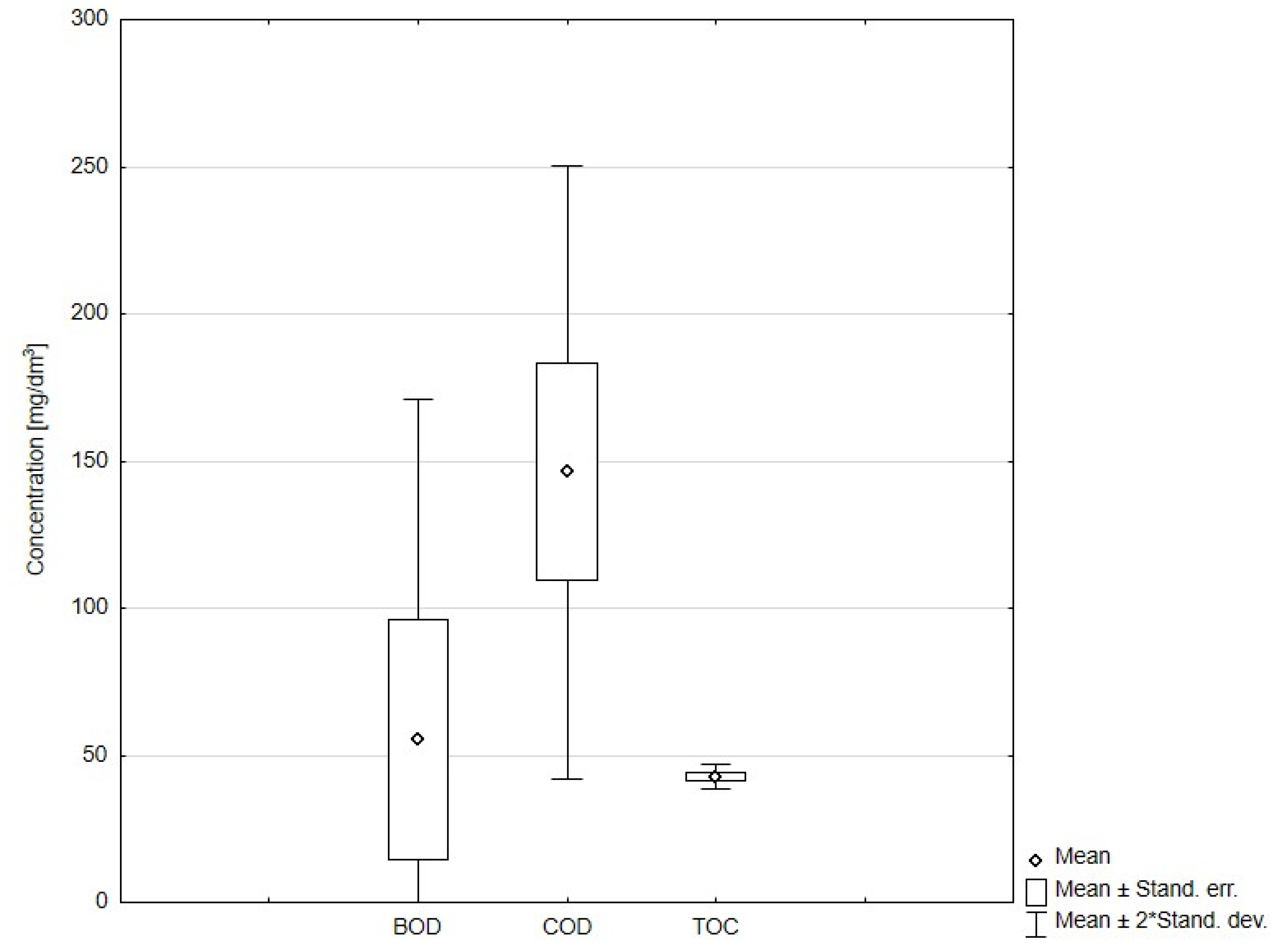

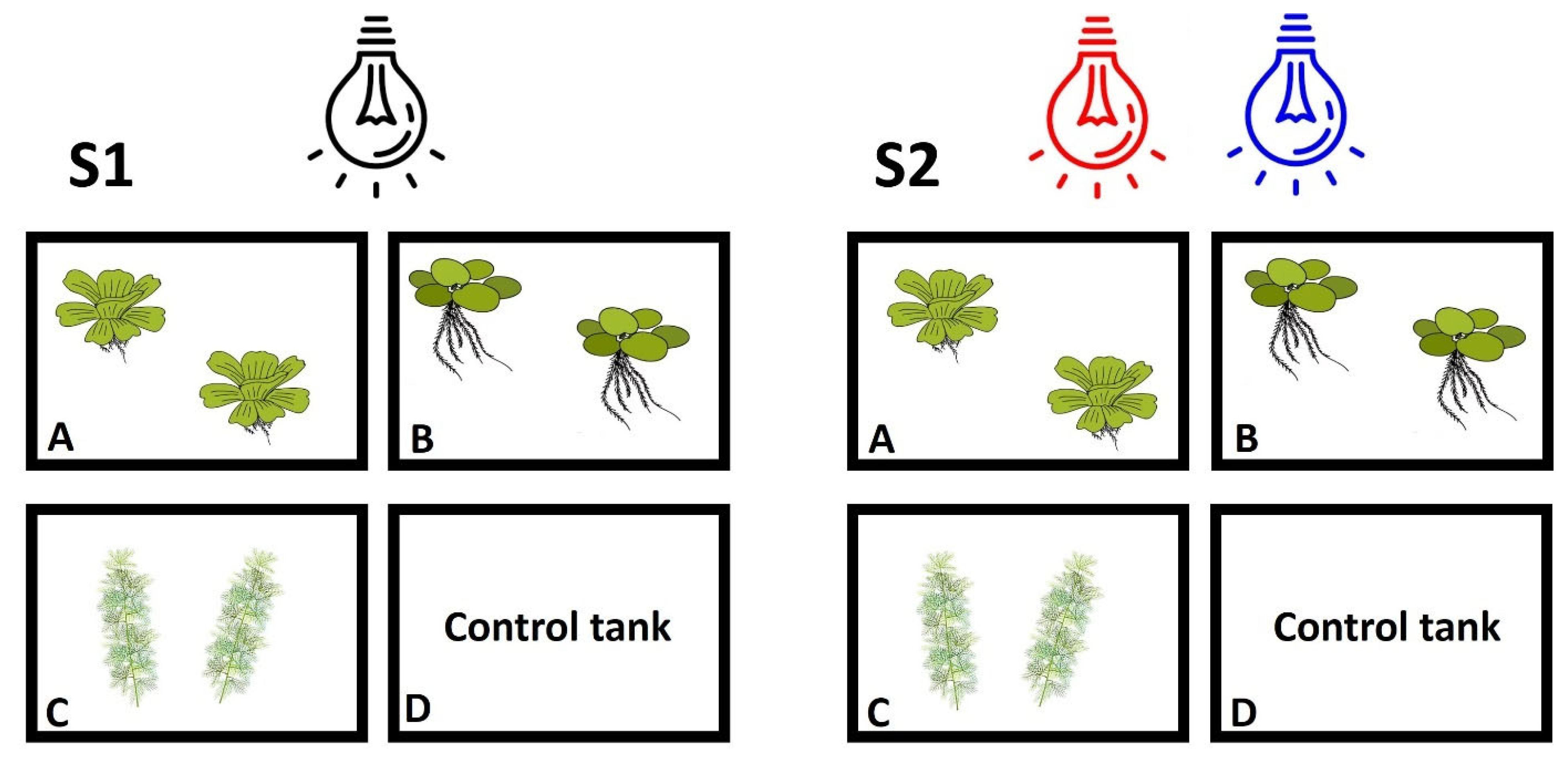

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Sampling and Analysis

- A = A665 − A750 the absorbance of the extract before acidification;

- Aa = A665 − A750 the absorbance of the extract after acidification;

- Ve the volume of the extract in milliliters;

- Vs the volume of the filtered sample in liters;

- Kc = 82 L/μg·cm the specific operational spectral absorption coefficient of chlorophyll a;

- R = 1.7 the ratio of A/Aa for a pure chlorophyll a solution that has been converted to pheophytin by acidification;

- d the optical path length of the cuvette, in centimeters;

- 103 the dimensional coefficient for adjusting Ve.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Algae Species Identification

3.2. Chlorophyll a Concentration

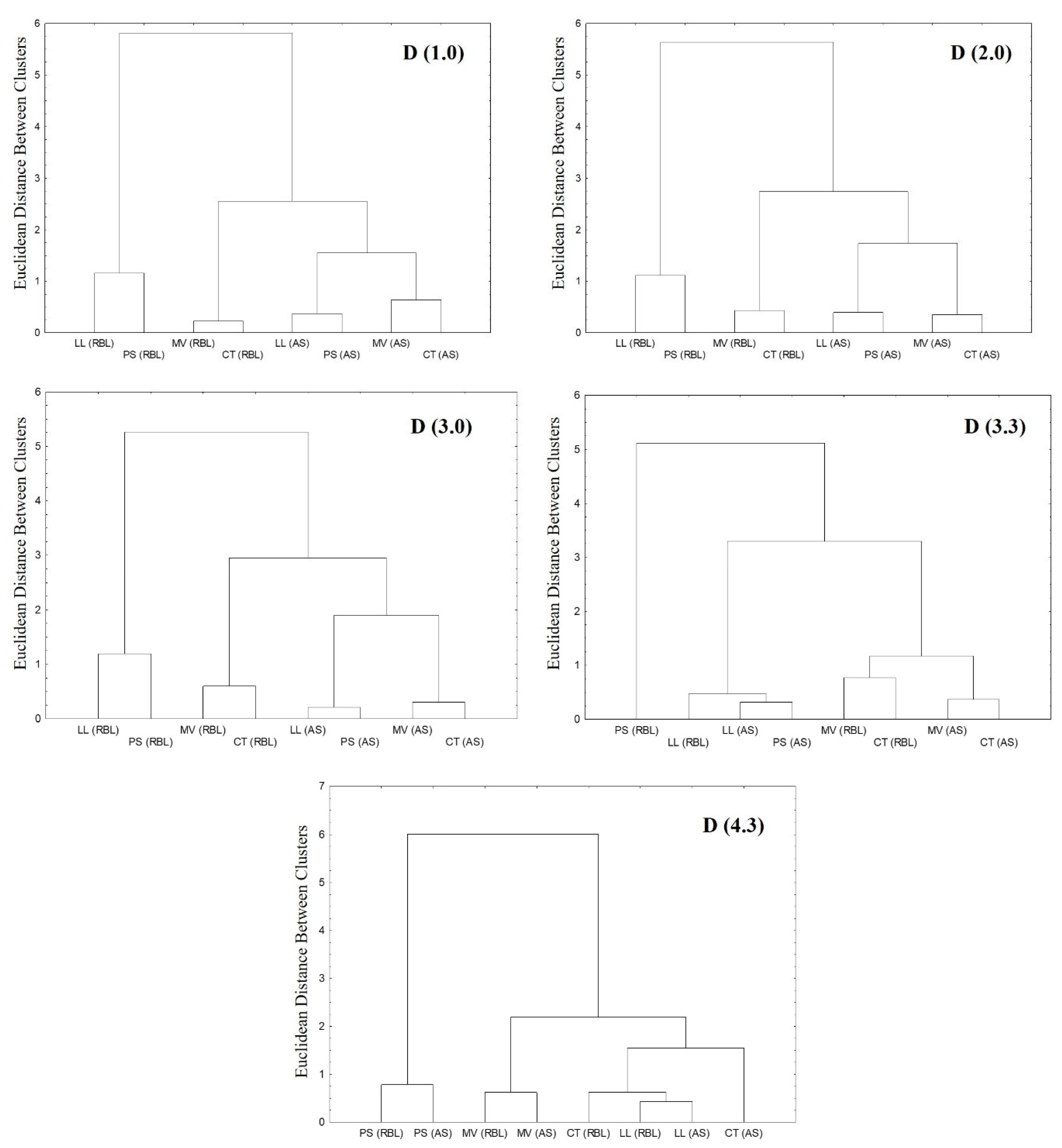

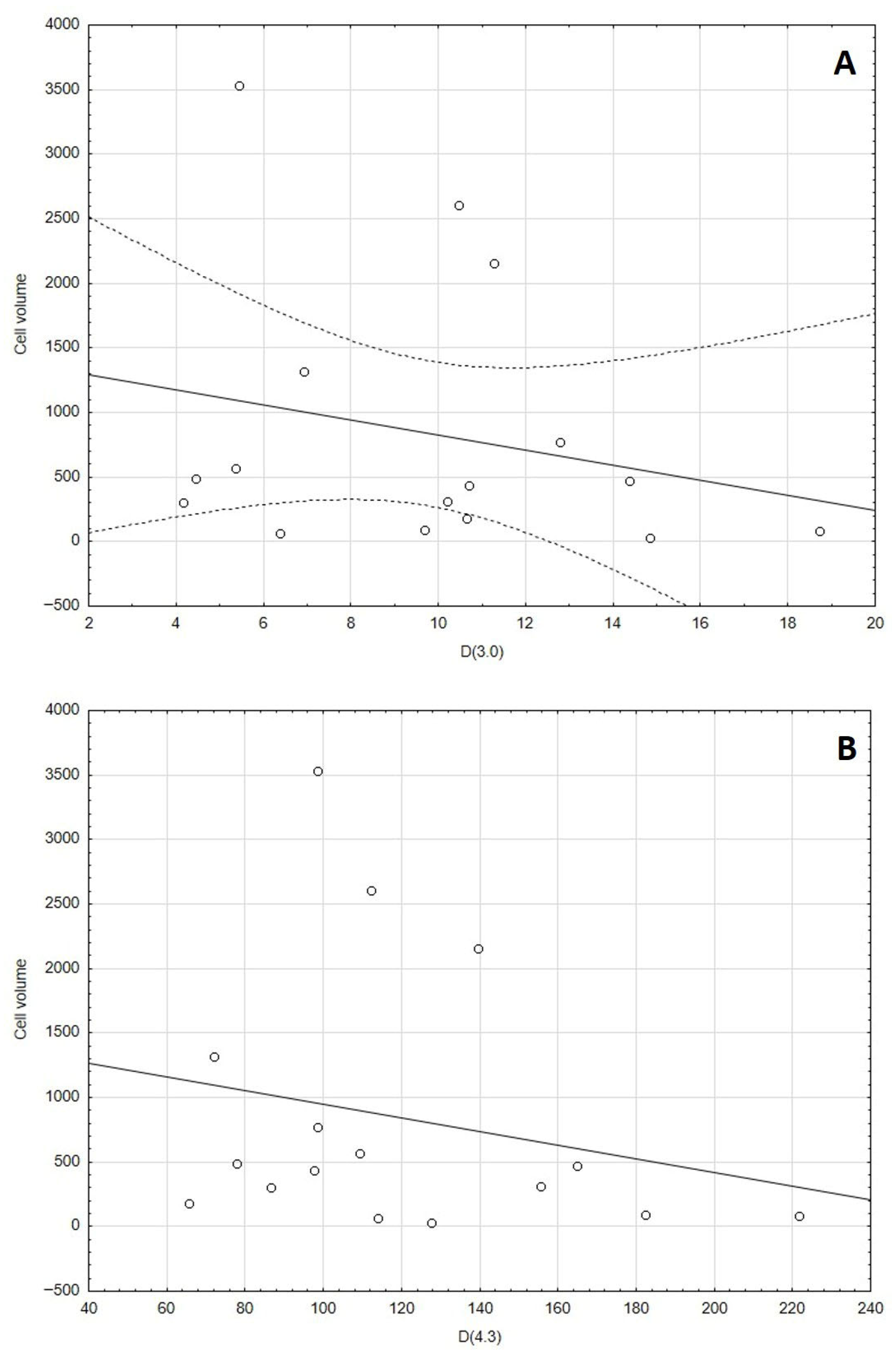

3.3. Granulometric Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boano, F.; Caruso, A.; Costamagna, E.; Ridolfi, L.; Fiore, S.; Demichelis, F.; Galvão, A.; Pisoeiro, J.; Rizzo, A.; Masi, F. A review of nature-based solutions for greywater treatment: Applications, hydraulic design, and environmental benefits. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environment Protection Authority Victoria. Code of Practice—Onsite Wastewater Management. In Guidelines for Environmental Management; Environment Protection Authority Victoria: Docklands, Australia, 2016; p. 891.4. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, S.; d’Antoni, B.M.; Bongards, M.; Chaparro, A.; Cronrath, A.; Fatone, F.; Lema, J.M.; Mauricio-Iglesias, M.; Soares, A.; Hospido, A. Monitoring and diagnosis of energy consumption in wastewater treatment plants. A state of the art and proposals for improvement. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 1251–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.L.; Valenzuela-Heredia, D.; Pedrouso, A.; Val del Río, A.; Belmonte, M.; Mosquera-Corral, A. Greenhouse gases emissions from wastewater treatment plants: Minimization, treatment, and prevention. J. Chem. 2016, 2016, 3796352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Melián, J.A. Sustainable Wastewater Treatment Systems (2018–2019). Sustainability 2020, 12, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liquetea, C.; Udias, A.; Conte, G.; Grizzetti, B.; Masi, F. Integrated valuation of a nature-based solution for water pollution control. Highlighting hidden benefits. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 22, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. (Eds.) Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H.; Platzer, C.; Winker, M.; von Muench, E. Technology Review of Constructed Wetlands; Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetlands for Greywater and Domestic Wastewater Treatment; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH: Eschborn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Worku, A.; Tefera, N.; Kloos, H.; Benor, S. Bioremediation of brewery wastewater using hydroponics planted with vetiver grass in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Avila, F.; Avil’es-Anazco, A.; Cabello-Torres, R.; Guanuchi-Quito, A.; Cadme-Galabay, A.M.; Guti’errez-Ortega, H.; Alvarez-Ochoa, R.; Zhindon-Arevalo, C. Application of ornamental plants in constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment: A scientometric analysis. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 7, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.J.; AL-surhanee, A.A.; Kouadri, F.; Ali, S.; Nawaz, N.; Afzal, M.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, B.; Soliman, M.H. Role of microorganisms in the remediation of wastewater in floating treatment wetlands: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokuolu, O.; Olokoba, S.; Aremu, S.; Olanlokun, O. Fish pond wastewater hydroponic treatment potential of Citrullus colocynthis. J. Res. For. Wildl. Environ. 2019, 11, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Tibebu, S.; Worku, A.; Angassa, K. Removal of Pathogens from Domestic Wastewater Using Small-Scale Gradual Hydroponics Planted with Duranta erecta, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 3182996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezbrytska, I.; Usenko, O.; Konovets, I.; Leontieva, T.; Abramiuk, I.; Goncharova, M.; Bilous, O. Potential Use of Aquatic Vascular Plants to Control Cyanobacterial Blooms: A Review. Water 2022, 14, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Pemberton, B.; Lewis, J.; Scales, P.J.; Martin, G.J.O. Wastewater treatment using filamentous algae—A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 298, 122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, P.; Malik, A.; Sreekrishnan, T.R.; Dalvi, V.; Gola, D. Selection of optimum combination via comprehensive comparison of multiple algal cultures for treatment of diverse wastewaters. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 18, 100758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.E.; Davis, K.; McColl, R.; Stanley, M.S.; Day, J.G.; Semião, A.J.C. Nitrogen uptake by the macro-algae Cladophora coelothrix and Cladophora parriaudii: Influence on growth, nitrogen preference and biochemical composition. Algal Res. 2018, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenpour, S.F.; Hennige, S.; Willoughby, N.; Adeloye, A.; Gutierrez, T. Integrating micro-algae into wastewater treatment: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 142168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Chen, P.; Min, M.; Zho, W.; Martinez, B.; Zhu, J.; Ruan, R. Characterization of a microalga Chlorella sp. well adapted to highly concentrated municipal wastewater for nutrient removal and biodiesel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 5138–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. Parametric Study of Brewery Wastewater Effluent Treatment Using Chlorella vulgaris Microalgae. Env. Eng. Res. 2016, 21, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, L.; Graça, S.; Sousa, C.; Ambrosano, L.; Ribeiro, B.; Botrel, E.P.; Neto, P.C.; Ferreira, A.F.; Silva, C.M. Microalgae biomass production using wastewater: Treatment and costs scale-up considerations. Algal Res. 2016, 16, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ho, S.H.; Cheng, C.L.; Guo, W.Q.; Nagarajan, D.; Ren, N.Q.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Perspectives on the feasibility of using microalgae for industrial wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 222, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbowski, T.; Bawiec, A.; Wiercik, P.; Pulikowski, K. Algae proliferation on substrates immersed in biologically treated sewage. J. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 18, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaas, H.E.; Paerl, H.W. Toxic Cyanobacteria: A Growing Threat to Water and Air Quality. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2021, 55, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Wang, P. Effects of rising atmospheric CO2 levels on physiological response of cyanobacteria and cyanobacterial bloom development: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 141889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schagerl, M.; Künzl, G. Chlorophyll a extraction from freshwater algae—A reevaluation. Biol. Bratisl. 2007, 62, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhu, R.; Zhou, Q.; Jeppsen, E.; Yang, K. Trophic status and lake depth play important roles in determining the nutrient-chlorophyll a relationship: Evidence from thousands of lakes globally. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawiec, A.; Pawęska, K.; Pulikowski, K. Analysis of granulometric composition of algal suspensions in wastewater treated with hydroponic method. Water Air Soil Poll. 2017, 228, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbowski, T.; Pulikowski, K.; Wiercik, P. Using laser granulometer to algae dynamic growth analysis in biological treated sewage. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 99, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Mirquez, L.; Lopes, F.; Taidi, B.; Pareau, D. Nitrogen and phosphate removal from wastewater with a mixed microalgae and bacteria culture. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 11, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Singh, P. Effect of temperature and light on the growth of algae species: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.F.; Salah, M.M.; Salman, J.M. Quantitative and qualitative variability of epiphytic algae on three aquatic plants in Euphrates River, Iraq. Iraq J. Aqua. 2007, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, E.I. Species composition and diversity of epiphytic microalgae on Myriophyllum spicatum in the El-Ibrahimia Canal, Egypt. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2021, 46, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starmach, K. Metody Badań Plankton; PWRiL: Warszawa, Poland, 1955; pp. 1–133. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Komàrek, J.; Fott, B. Chlorophyceae (Grünalgen). Ordnung: Chlorococcales. In Das Phytoplankton des Süβwassers. Systematik und Biologie; Huber-Pestalozzi, G., Ed.; Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung: Stuttgart, Germany, 1983; Volume 7, pp. 1–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprokaryota: Chroococcales. In Süβwasserflora von Mitteleuropa 19; Pascher, A., Ed.; Gustav Fischer Verlag: Jena, Germany; Stuttgart, Germany, 1993; pp. 1–549. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Cyanoprocaryota: Oscillatoriales II. In Süβwasserflora von Mitteleuropa 19; Büdel, A.B., Krienitz, L., Gärtner, G., Schagerl, M., Eds.; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 1–759. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, M.; Witkowski, A.; Żelazna-Wieczorek, J.; Wojtal, A.Z.; Szczeponka, E.; Szulc, K.; Szulc, B. Klucz do Oznaczania Okrzemek w Fitobentosie na Potrzeby Oceny Stanu Ekologicznego wód Powierzchniowych w Polsce; Biblioteka Monitoringu Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 2012; pp. 1–452. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škaloud, P.; Rindi, F.; Boedeker, C.; Leliaert, F. Chlorophyta: Ulvophyceae. In Süβwasserflora von Mitteleuropa Freshwater Flora of Central Europe 13; Büdel, W.B., Gärtner, G., Krienitz, L., Schagerl, M., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, C.; Mann, D.G.; Johns, H.M. Alga: An Introduction to Phycology; Great Britain at University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 1–623. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10260; Water quality—Measurement of biochemical parameters—Spectrometric determination of the chlorophyll-a concentration. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992.

- Schagerl, M.; Müller, B. Acclimation of chlorophyll a and carotenoid levels to different irradiances in four freshwater cyanobacteria. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 163, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczyńska, P.; Jemioła-Rzemińska, M.; Strzałka, K. Photosynthetic Pigments in Diatoms. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5847–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Saavedra, M.P.; Voltolina, D. Effect of photon fluence rates of white and blue-green light on growth efficiency and pigment content of three diatom species in batch cultures. Cienc. Marin. 2002, 28, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, E.S. Effect of growth factors and light quality on the growth, pigmentation and photosynthesis of two diatoms, Thalassiosira gravida and Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mar. Biol. 1985, 86, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.H.; Jakob, T.; Wilhelm, C. Balancing the energy flow from captured light to biomass under fluctuating light conditions. New Phytol. 2006, 169, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masojídek, J.; Kopecký, J.; Koblížek, M.; Torzillo, G. The Xanthophyll Cycle in Green Algae (Chlorophyta): Its Role in the Photosynthetic Apparatus. Plant Biol. 2004, 6, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenpour, S.F.; Richards, B.; Willoughby, N. Spectral conversion of light for enhanced microalgae growth rates and photosynthetic pigment production. Bioresour Technol. 2012, 125, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, B.; Pancha, I.; Desai, C.; Chokshi, K.; Paliwal, C.; Ghosh, T.; Mishra, S. Effects of different media composition, light intensity and photoperiod on morphology and physiology of freshwater microalgae Ankistrodesmus falcatus—A potential strain for biofuel production. Bioresour Technol. 2014, 171, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliński, A. Basic issues related to the measurement of size and particle size distribution. Trans. Foundry Res. Inst. 2013, 53, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kuśnierz, M.; Wiercik, P. Analysis of particle size and fractal dimensions of suspensions contained in raw sewage, treated sewage and activated sludge. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2016, 42, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, G.; Arcila, J.S.; Buitrón, G. Microalgal-bacterial aggregates: Applications and perspectives for wastewater treatment. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, A.; Bonifacio, M.; He, J. Effects of Light Quality Adjustment in Microalgal Cultivation. Processes 2025, 13, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutorowicz, A. Opracowanie Standardowych OBJĘTOŚCI Komórek do Szacowania Biomasy Wybranych Taksonów Glonów Planktonowych Wraz z Określeniem Sposobu Pomiarów i Szacowania [Development of Standard Cell Volume Estimation for Planktonic Algae biomass Determination]; GIOŚ: Olsztyn, Poland, 2006. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Matter, I.A.; Bui, V.K.H.; Jung, M.; Seo, J.Y.; Kim, Y.-E.; Lee, Y.-C.; Oh, Y.-K. Flocculation Harvesting Techniques for Microalgae: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzoejinwa, B.B.; Asoiro, F.U. Algae Harvesting. In Value-Added Products from Algae; Abomohra, A., Ende, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Artificial Light Imitating Sunlight | Red and Blue Light | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | START | CT 5W | CT 15W | P 5W | P 15W | L 5W | L 15W | M 5W | M 15W | CT 5W | CT 15W | P 5W | P 15W | L 5W | L 15W | M 5W | M 15W |

| Phylum Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) | |||||||||||||||||

| Aphanocapsa incerta (Lemm.) Cronberg et Komárek | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Aphanocapsa nubilum Komárek et Kling | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Eucapsis minor (Skuja) Elenkin | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Eucapsis sp. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Komvophoron sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Leptolyngbya sp. | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Limnothrix redekei (Van Goor) Meffert | 2 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Planctolyngbya limnetica (Lemm.) Komárkova-Legnerová et Cronberg | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Planctolyngbya sp. | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Phylum Heterokontophyta | |||||||||||||||||

| Class Bacillariophyceae (diatoms) | |||||||||||||||||

| Achnantidium sp. 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Coconeis sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| cf. Achnantidium sp. 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||

| cf. Pinnularia | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Diatoma sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Diatoma vulgaris Bory | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Eunotia bilunaris (Ehrenberg) Schaarschmidt | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Fragilaria sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Gomphonema parvulum Lange-Bertalot, Richard | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Lemnicola hungarica (Grunow) Round, Basson | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Navicula radiosa Kützing | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Navicula schmassmannii Hustedt | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Navicula sp. 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Navicula sp. 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Navicula sp. 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Nitzschia palea (Kützing) W. Smitch | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Pinnularia gibba Ehrenberg | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Stauroneisis sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Tabellaria sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Phylum Chlorophyta (green algae) | |||||||||||||||||

| Ankistrodesmus fusiformis Corda | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Characium ensiforme Hermann | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Chlamydomonas sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Chlorella sp. 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Chlorella sp. 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Dicyosphaerium pulchellum Wod | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Kirchneriella cf. rotunda (Kors) Hindak | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Monoraphidium cf. fontinale Hind. | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Monoraphidium griffithii (Berk.) Kom.-Legn. | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Monoraphidium komarkovae Nyg. | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Mougeotia sp. | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Oedogonium sp. | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Planktonema lauterbornii Schmidle | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pseudoclonium sp. | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Radiococcus sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Scenedesmus acutus Meyen | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Scenedesmus obliquus (Turpin) Kützing | 2 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| Tetracistis sp. | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ulothrix tenerrima Kützing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Ulotrix tenuissima Kützing | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| First Measurement Series | Chl a Concentration [μg/dm3] | Dominant Identified Organisms * | Chl a Concentration [μg/dm3] | Dominant Identified Organisms * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Light | Type of Plant | 5 Weeks | 15 Weeks | ||

| ARTIFICIAL LIGHT IMITATING SUNLIGHT | Control tank | 38.21 | diatoms (3) + blue-green algae (2) | 3100.28 | diatoms (2) + green algae (2) |

| Pistia stratiotes | 28.87 | diatoms (2) + blue-green algae (3) | 5.57 | diatoms (3) | |

| Limnobium laevigatum | 17.89 | diatoms (2) + blue-green algae (1) | 399.35 | Diatoms (2) + blue-green algae (1) | |

| Myriophyllum verticillatum | 47.27 | diatoms (3) + blue-green algae (2) | 714.59 | diatoms (2) | |

| RED AND BLUE LIGHT | Control tank | 2391.25 | green algae (3) + diatoms (3) | 2290.44 | green algae (3) + diatoms (2) |

| Pistia stratiotes | 73.86 | diatoms (4) | 2.13 | diatoms (4) | |

| Limnobium laevigatum | 62.25 | diatoms (4) | 319.98 | diatoms (2) | |

| Myriophyllum verticillatum | 1187.45 | green algae (4) + diatoms (4) | 4148.59 | green algae (4) + diatoms (4) | |

| Particles Diameters | D(1.0) | D(2.0) | D(3.0) | D(3.2) | D(4.3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Light | Type of Plant | 5 Weeks | 15 Weeks | 5 Weeks | 15 Weeks | 5 Weeks | 15 Weeks | 5 Weeks | 15 Weeks | 5 Weeks | 15 Weeks |

| ARTIFICIAL LIGHT IMITATING SUNLIGHT | Control tank | 3.805 | 2.305 | 6.128 | 3.030 | 10.660 | 5.350 | 32.266 | 16.683 | 65.669 | 71.907 |

| Pistia stratiotes | 3.216 | 3.425 | 5.233 | 5.214 | 10.203 | 9.684 | 38.788 | 33.408 | 155.573 | 182.494 | |

| Limnobium laevigatum | 3.698 | 3.498 | 5.978 | 5.681 | 10.692 | 10.455 | 34.200 | 35.404 | 97.672 | 112.270 | |

| Myriophyllum verticillatum | 3.926 | 1.158 | 6.165 | 1.995 | 11.285 | 4.173 | 37.821 | 18.266 | 139.565 | 86.498 | |

| RED AND BLUE LIGHT | Control tank | 2.228 | 1.609 | 2.893 | 2.441 | 5.439 | 4.455 | 19.228 | 14.836 | 98.467 | 77.958 |

| Pistia stratiotes | 5.467 | 6.649 | 8.336 | 10.598 | 14.375 | 18.718 | 72.748 | 58.386 | 164.817 | 221.624 | |

| Limnobium laevigatum | 5.670 | 4.579 | 8.865 | 7.424 | 14.854 | 12.785 | 41.707 | 37.909 | 109.382 | 98.560 | |

| Myriophyllum verticillatum | 2.169 | 2.010 | 3.557 | 3.293 | 6.935 | 6.380 | 26.356 | 23.948 | 127.755 | 113.879 | |

| Species | Cell Volume |

|---|---|

| Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) | |

| Limnothrix redekei (Van Goor) Meffert | 176.6 |

| Planctolyngbya sp. | 314.0 |

| Bacillariophyceae (diatoms) | |

| Achnantidium sp. | 435.7 |

| Diatoma anceps (Erenberg) Kirchner | 2154.8 |

| Diatoma vulgaris Bory | 3532.5 |

| Gomphonema parvulum Lange-Bertalot, Richard | 474.9 |

| Lemnicola hungarica (Grunow) Round, Basson | 565.2 |

| Navicula schmassmannii Hustedt | 29.6 |

| Navicula sp. 2 | 1316.3 |

| Nitzschia palea (Kützing) W. Smitch | 94.5 |

| Pinnularia gibba Ehrenberg | 2610.1 |

| Chlorophyta (green algae) | |

| Ankistrodesmus fusiformis Corda | 307.7 |

| Characium ensiforme Hermann | 490.9 |

| Monoraphidium cf. fontinale Hind. | 81.6 |

| Monoraphidium griffithii (Berk.) Kom.-Legn. | 771.5 |

| Monoraphidium komarkovae Nyg. | 62.0 |

| Mougeotia sp. | 49,000.0 |

| Oedogonium sp. | 2400.0 |

| Pseudoclonium sp. | 2150.0 |

| Scenedesmus acutus Meyen | 332.3 |

| Scenedesmus obliquus (Turpin) Kützing | 230.8 |

| Ulothrix tenerrima Kützing | 5700.0 |

| Ulothrix tenuissima Kützing | 10,400.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bawiec, A.; Pawęska, K.; Richter, D.; Pietryka, M. Hydroponic Nature-Based Wastewater Treatment: Changes in Algal Communities and the Limitations of Laser Granulometry for Taxonomic Identification. Sustainability 2026, 18, 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020909

Bawiec A, Pawęska K, Richter D, Pietryka M. Hydroponic Nature-Based Wastewater Treatment: Changes in Algal Communities and the Limitations of Laser Granulometry for Taxonomic Identification. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020909

Chicago/Turabian StyleBawiec, Aleksandra, Katarzyna Pawęska, Dorota Richter, and Mirosława Pietryka. 2026. "Hydroponic Nature-Based Wastewater Treatment: Changes in Algal Communities and the Limitations of Laser Granulometry for Taxonomic Identification" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020909

APA StyleBawiec, A., Pawęska, K., Richter, D., & Pietryka, M. (2026). Hydroponic Nature-Based Wastewater Treatment: Changes in Algal Communities and the Limitations of Laser Granulometry for Taxonomic Identification. Sustainability, 18(2), 909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020909