The Impact of Electric Charging Unit Conversion on the Performance of Fuel Stations Located in Urban Areas: A Sustainable Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction and Literature Review

2. Problem

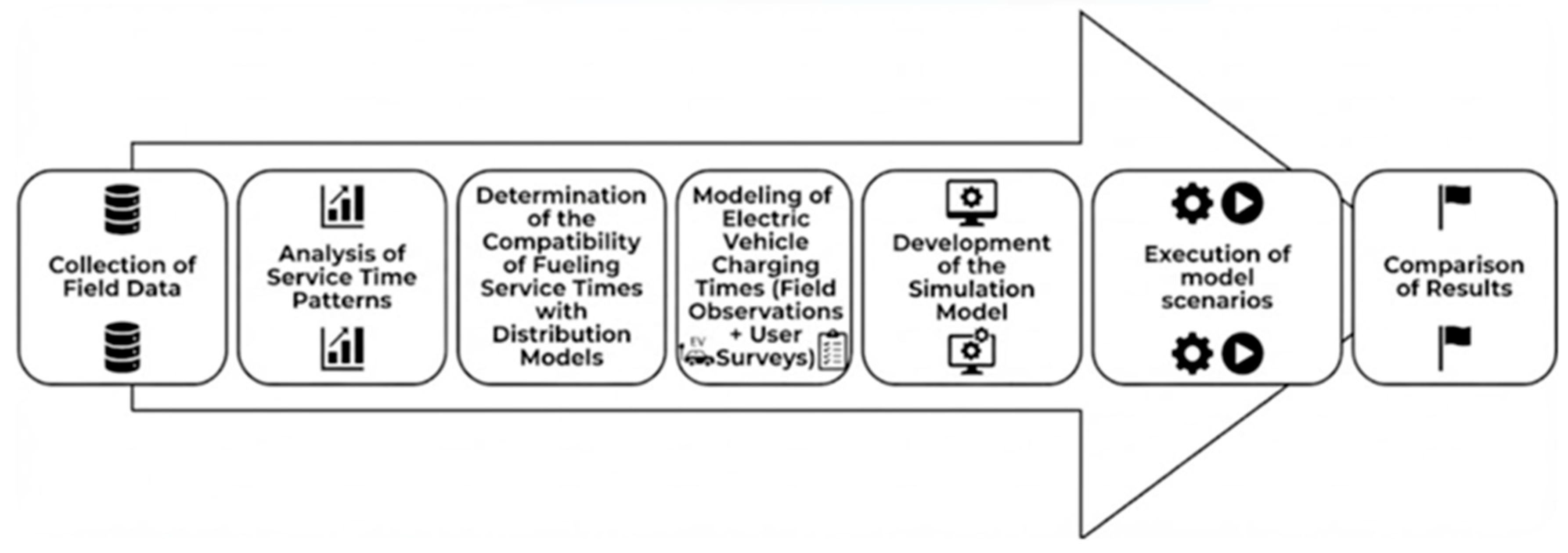

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area and Characteristics

3.2. Collection of Field and Survey Data

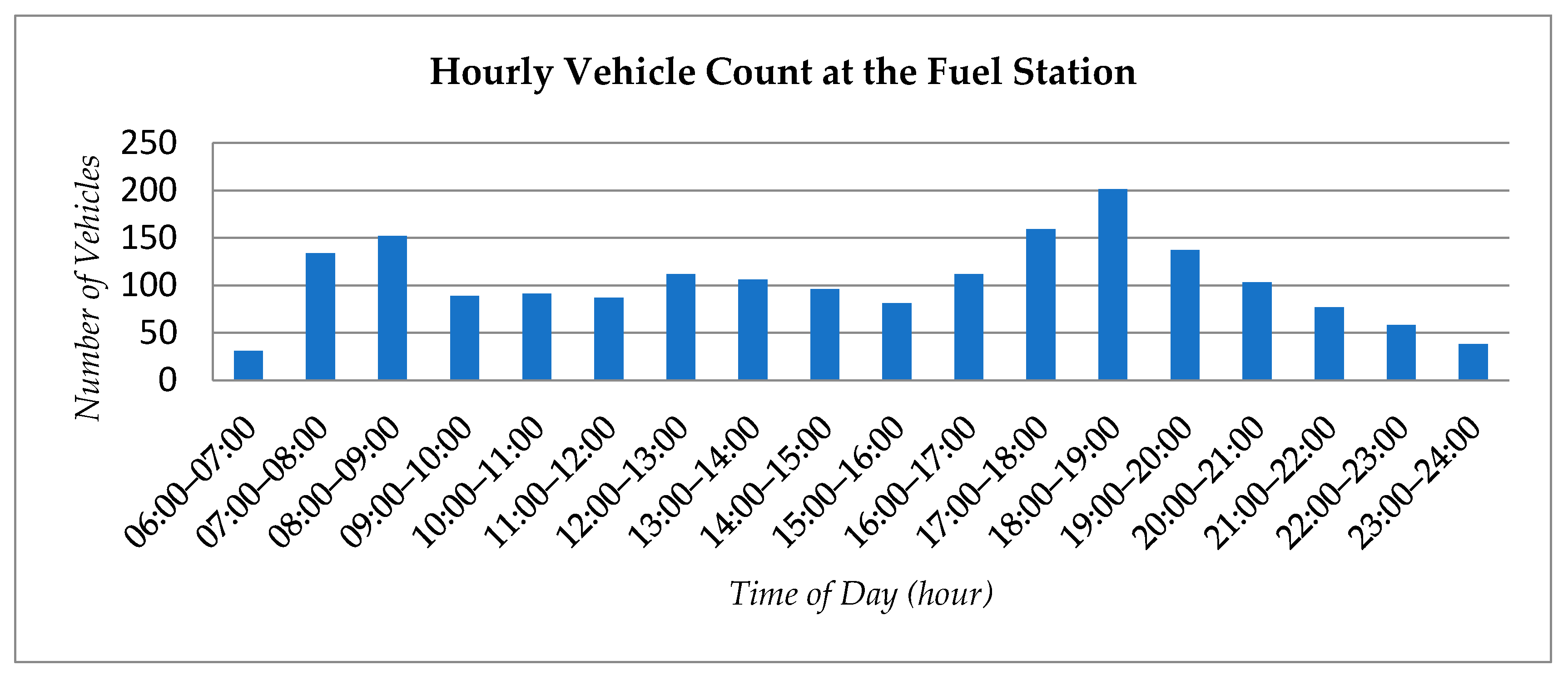

3.2.1. Fuel Station Data

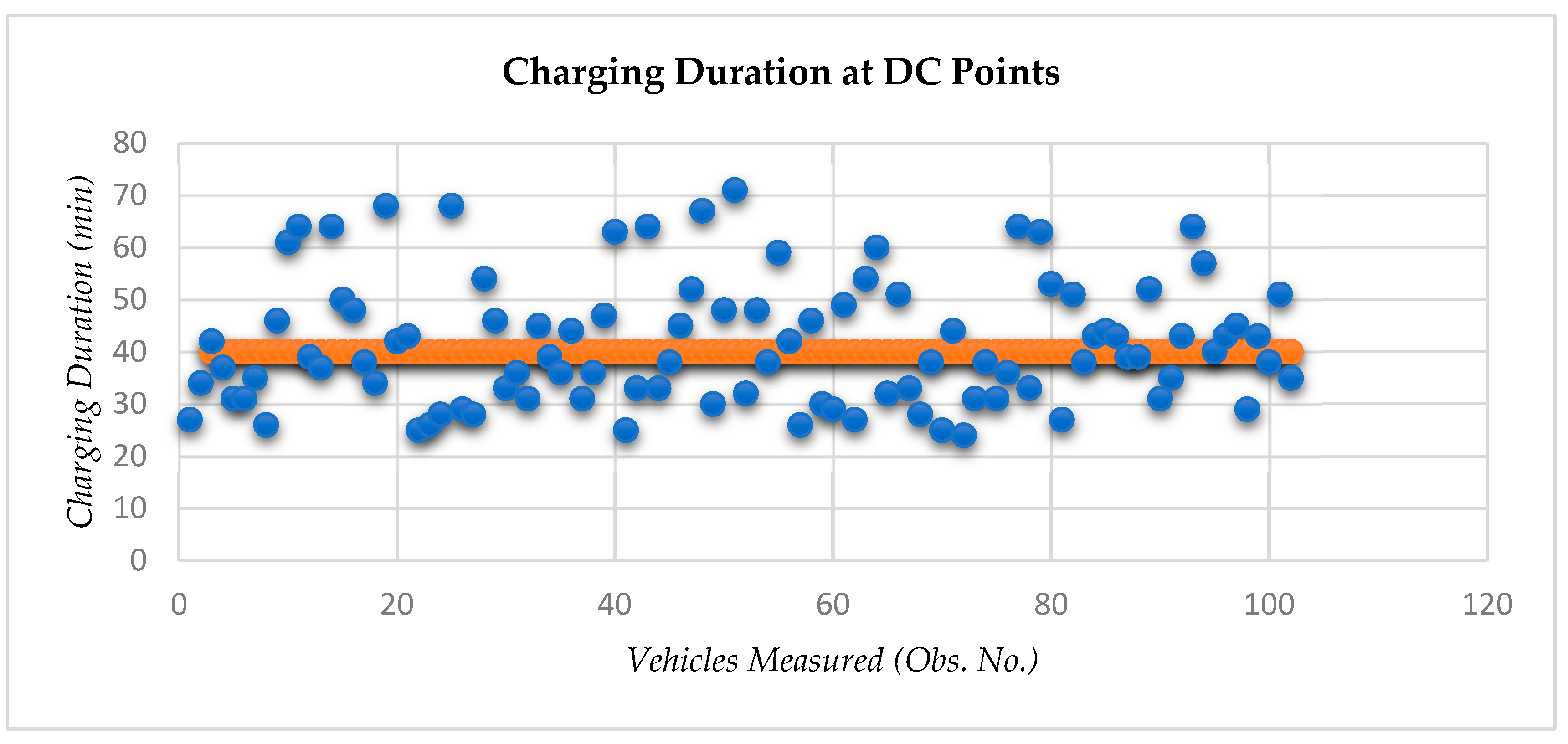

3.2.2. Total Occupancy Time at DC Fast Charging Stations: A Realistic Dataset for Modeling

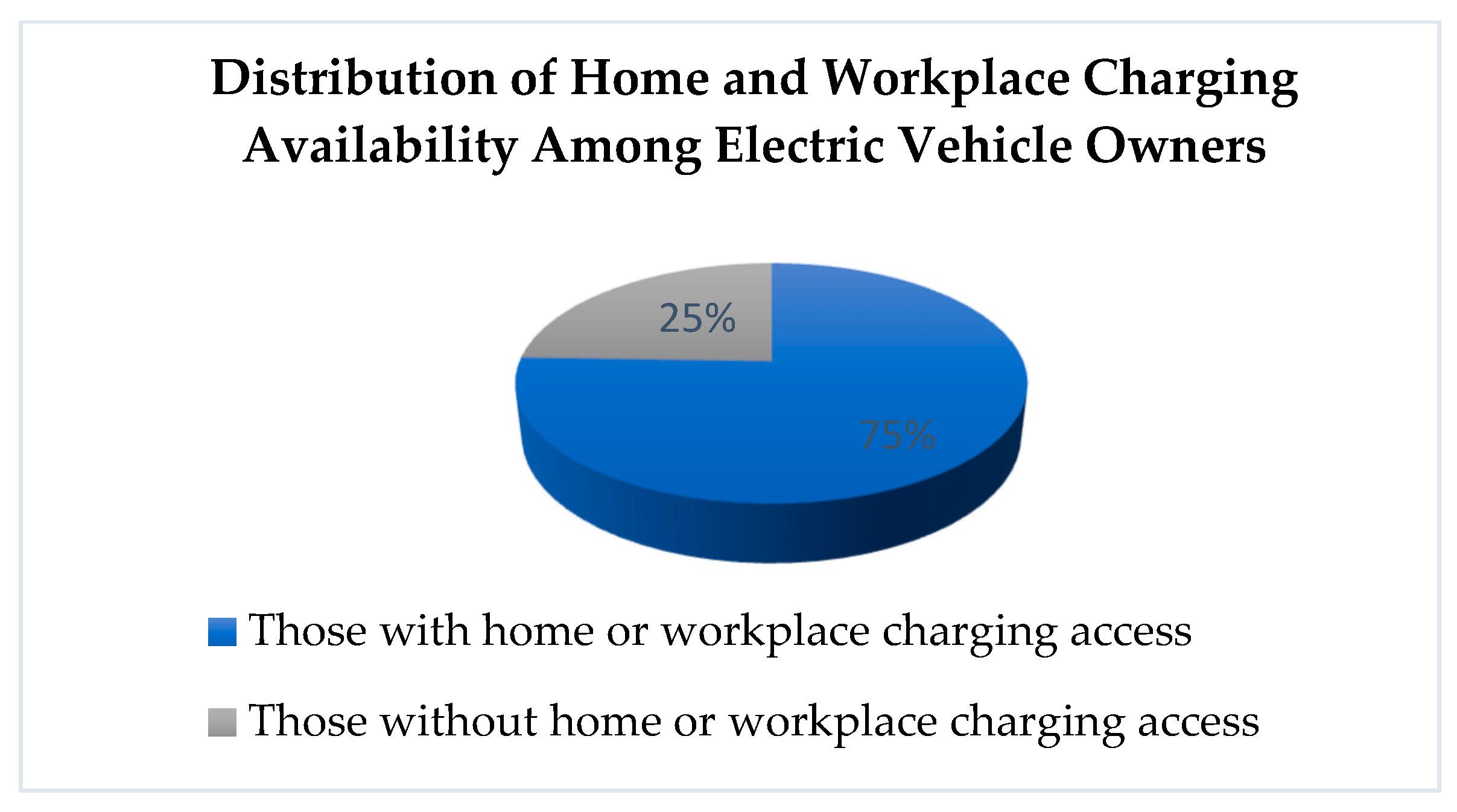

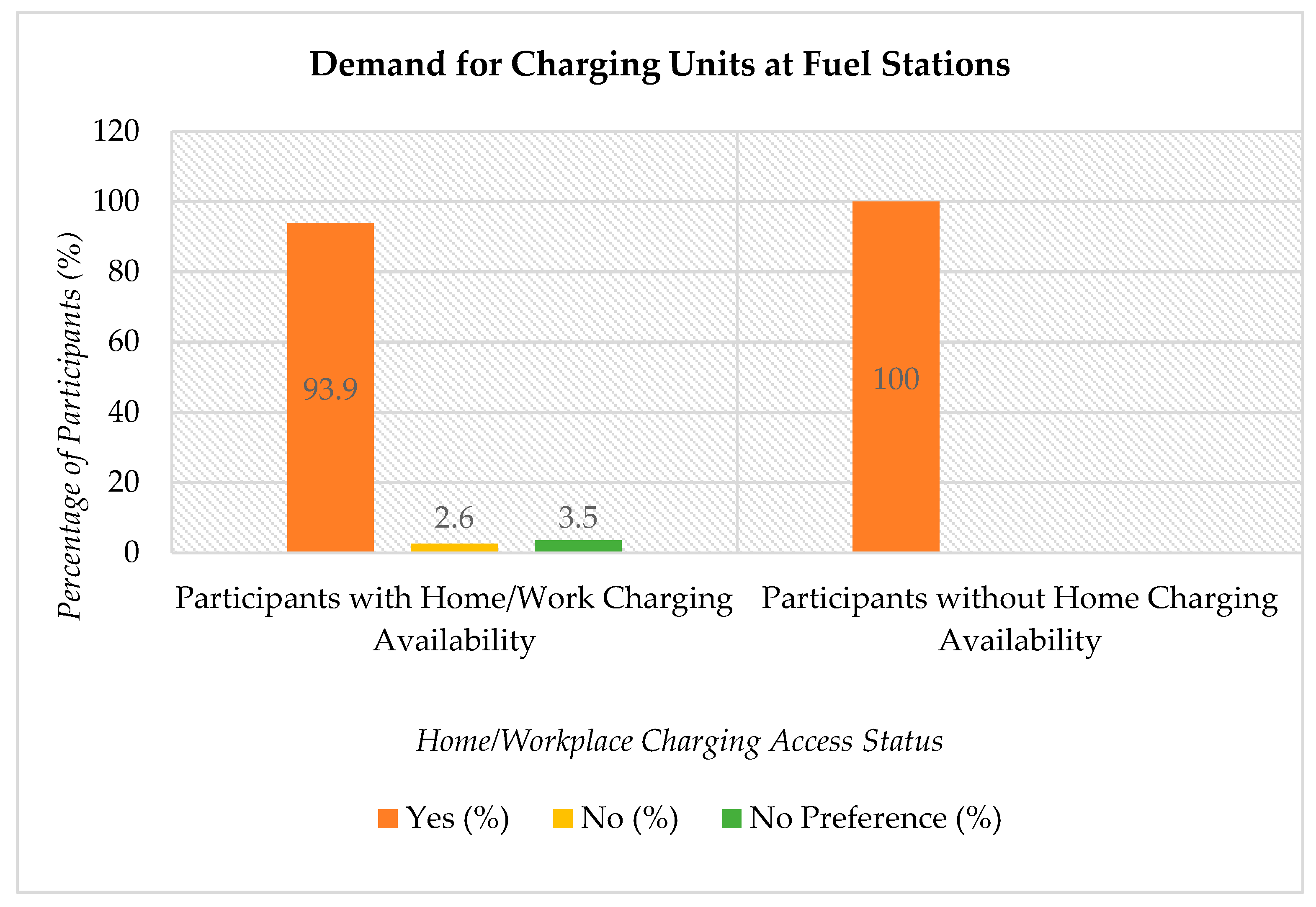

3.2.3. Survey Methodology for Examining EV User Behavior and Future Adoption Tendencies

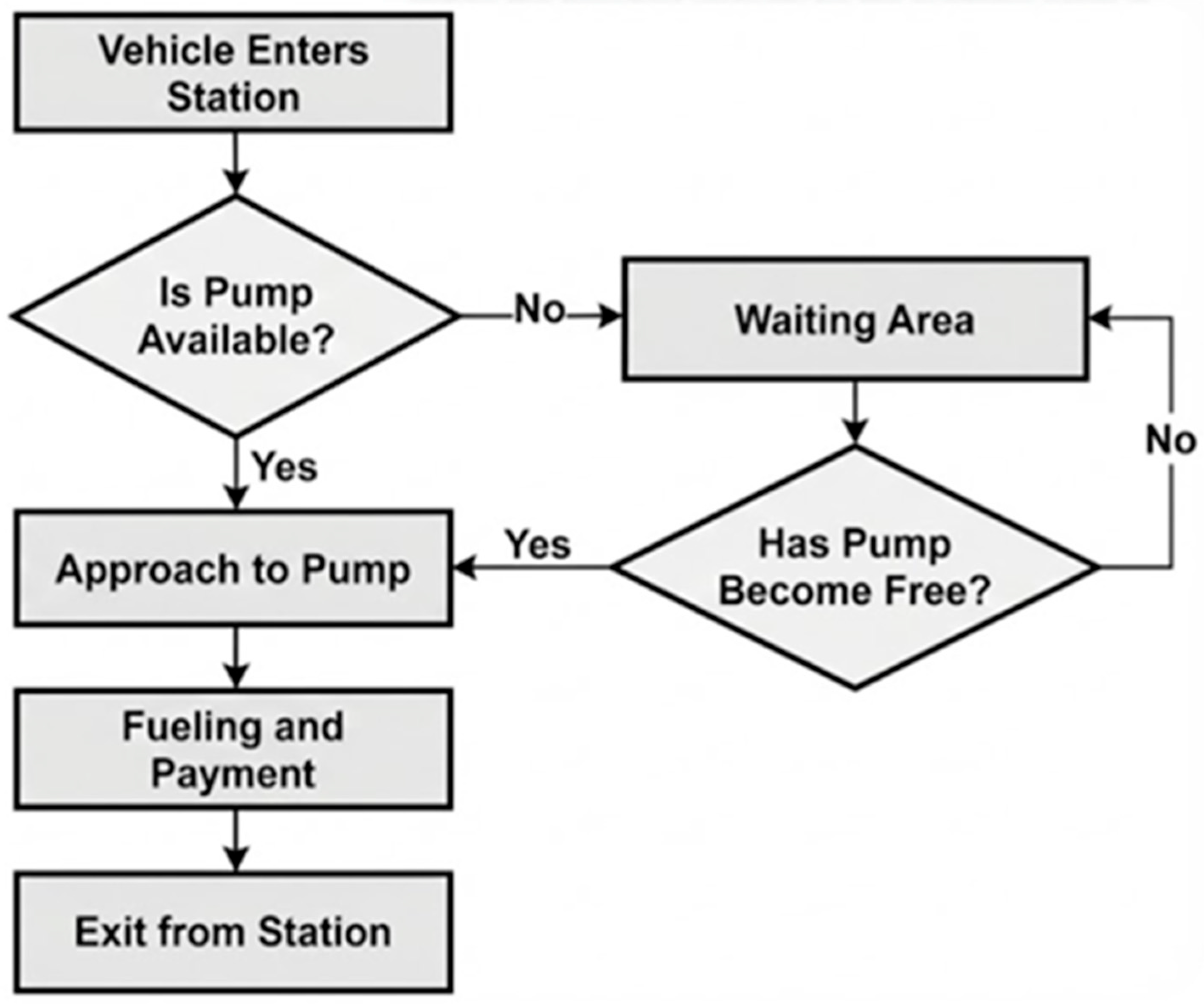

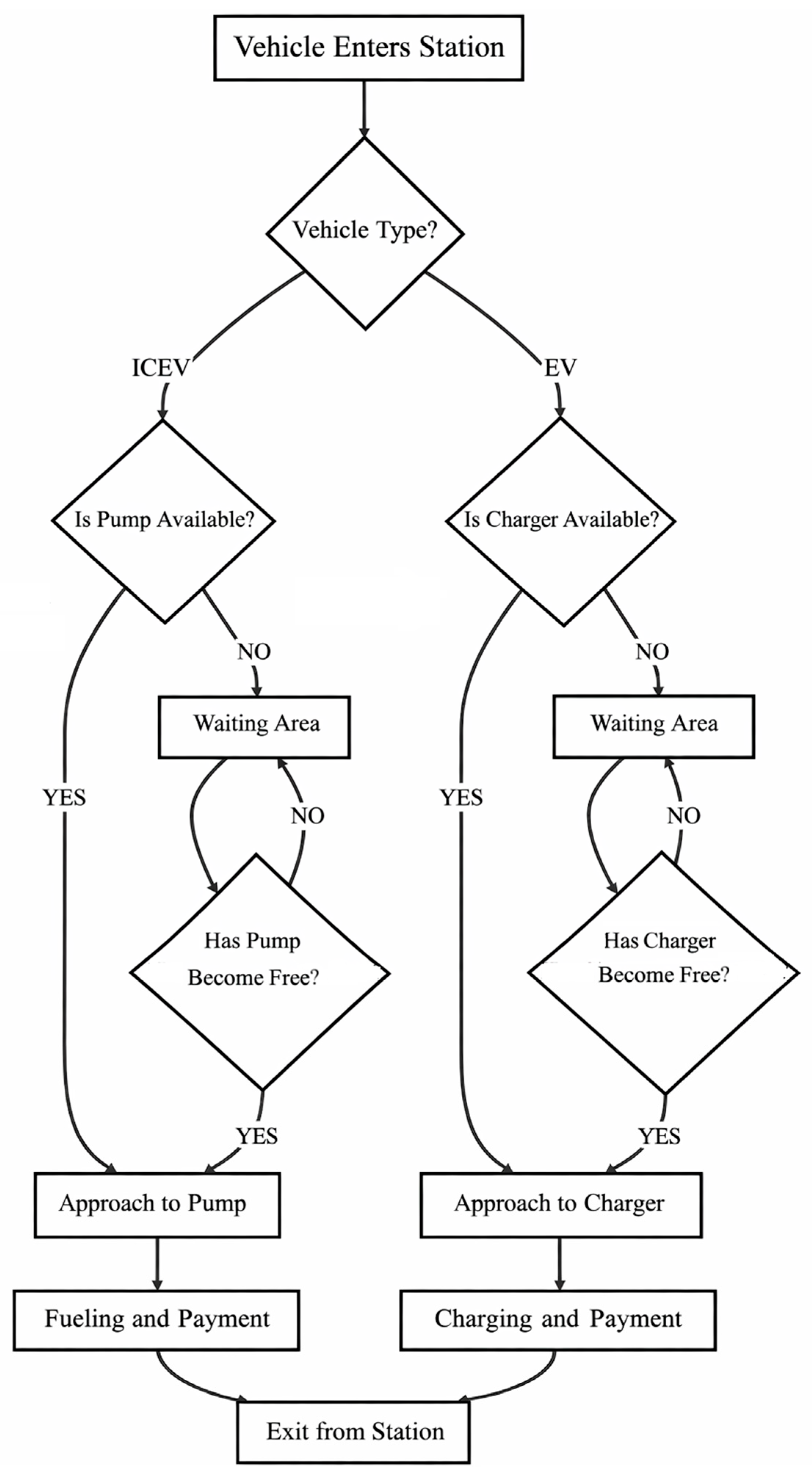

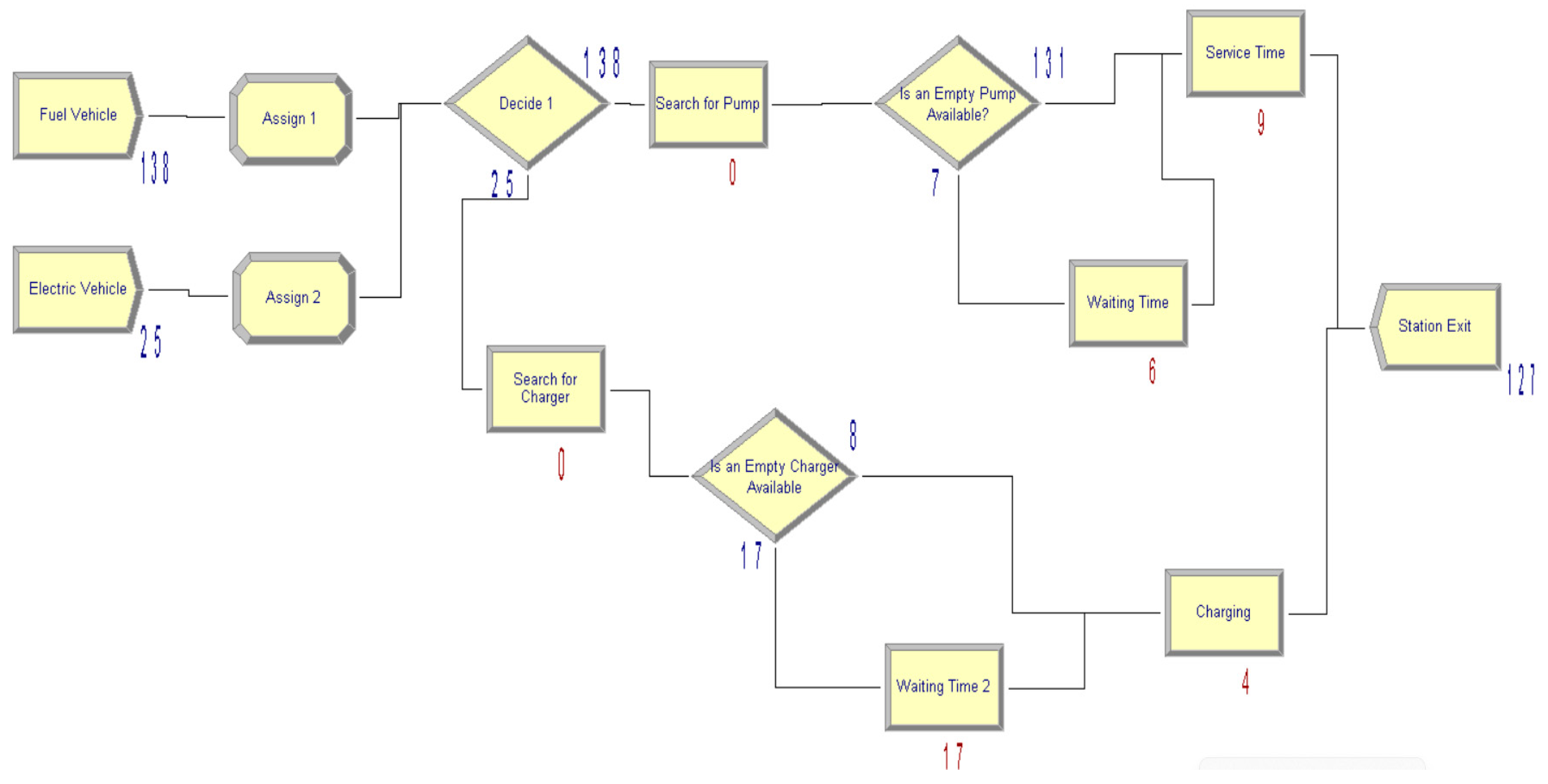

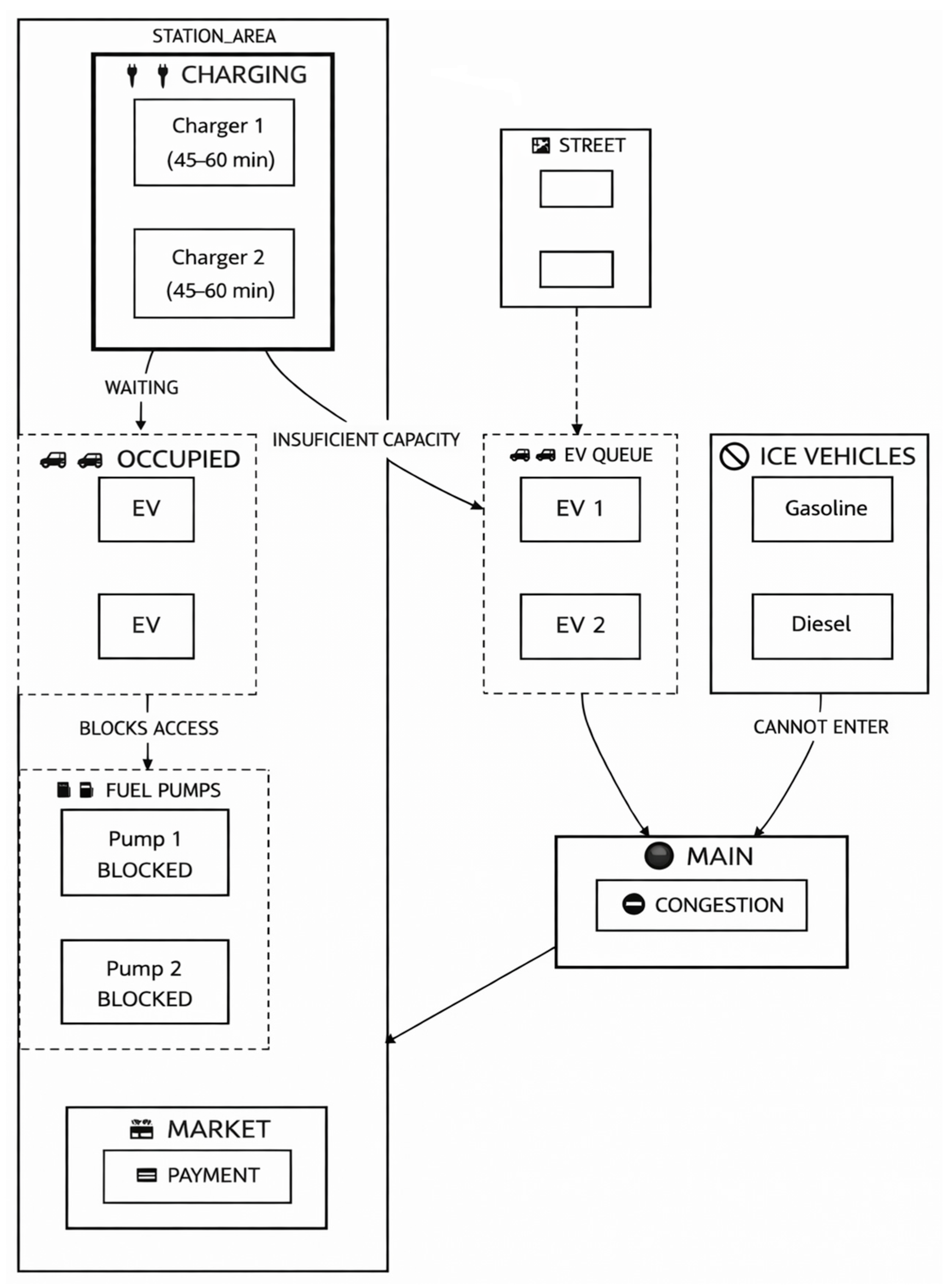

3.3. Simulation-Based Modeling of the Fuel Station

3.4. Growth Scenarios for EV Penetration in Turkey

4. Results

4.1. Fuel Stations and DC Fast-Charging Stations

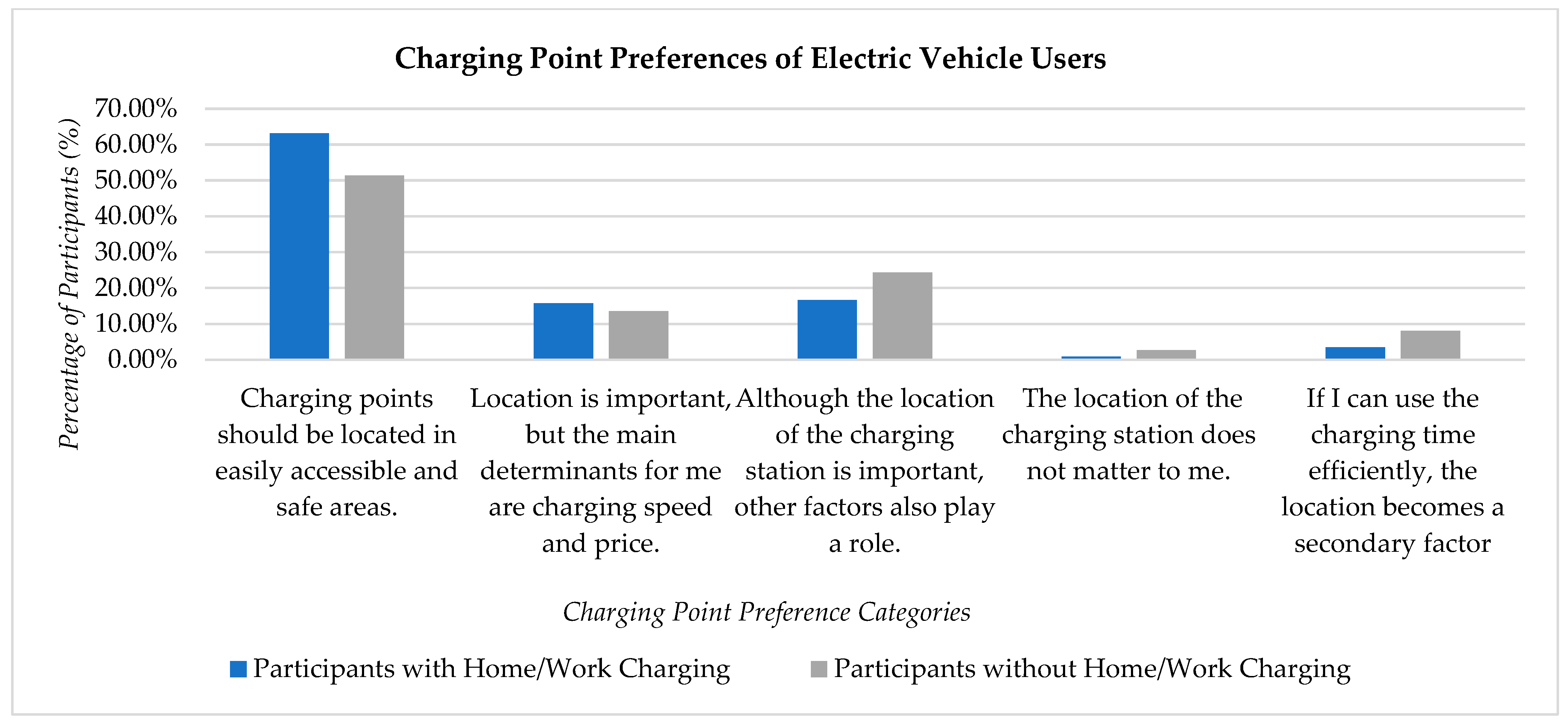

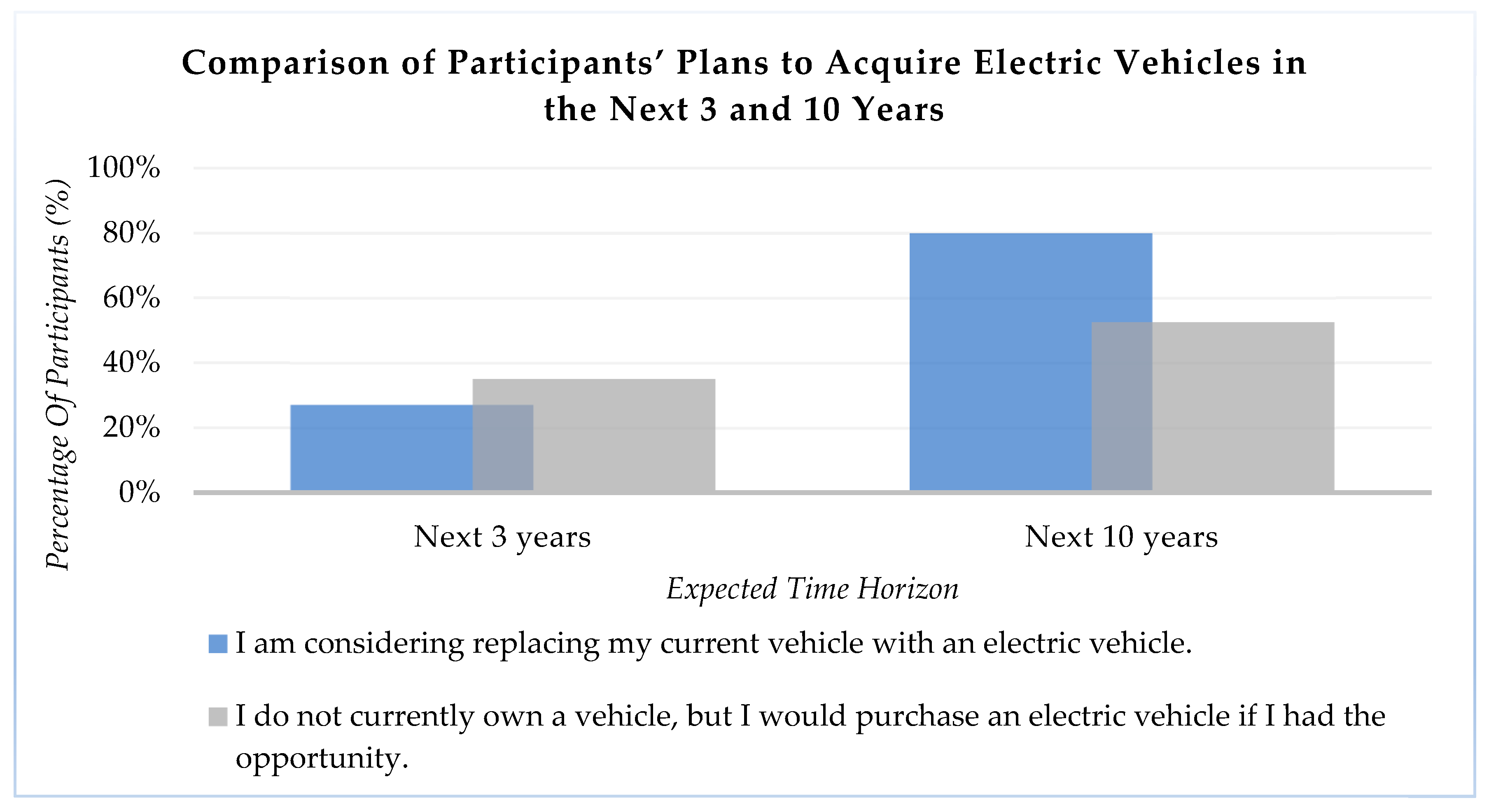

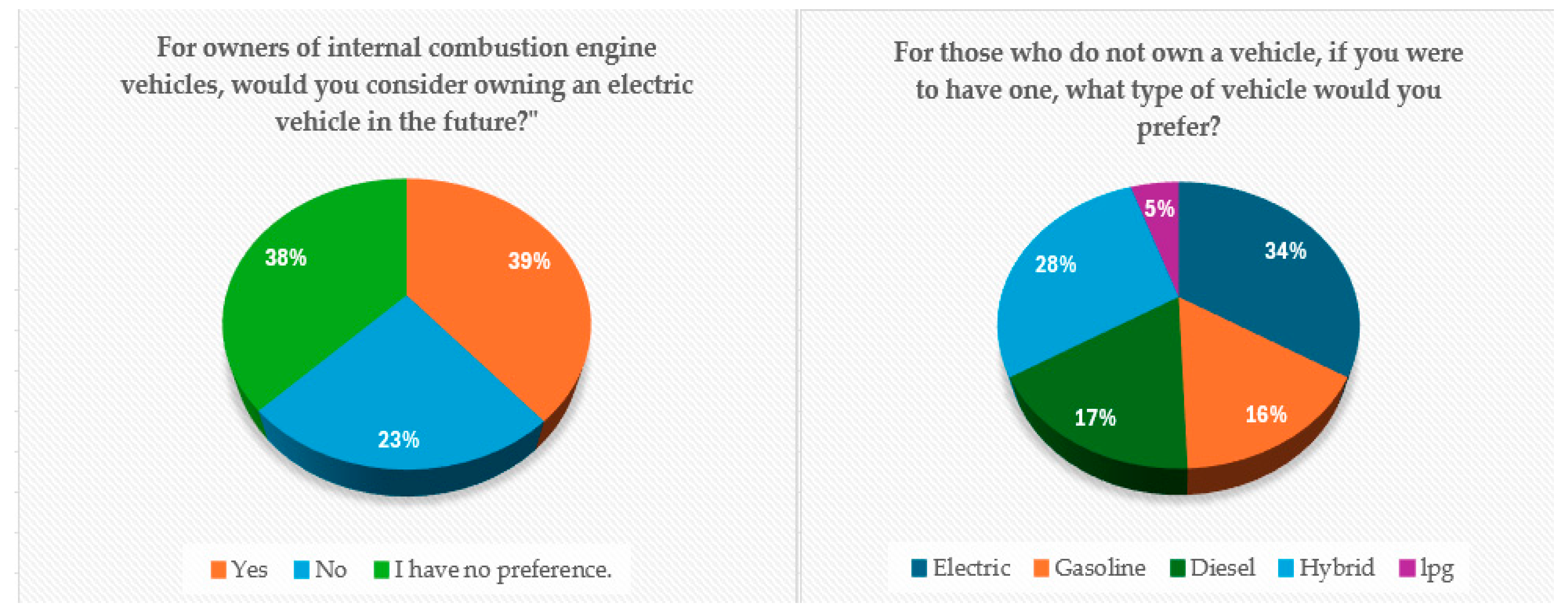

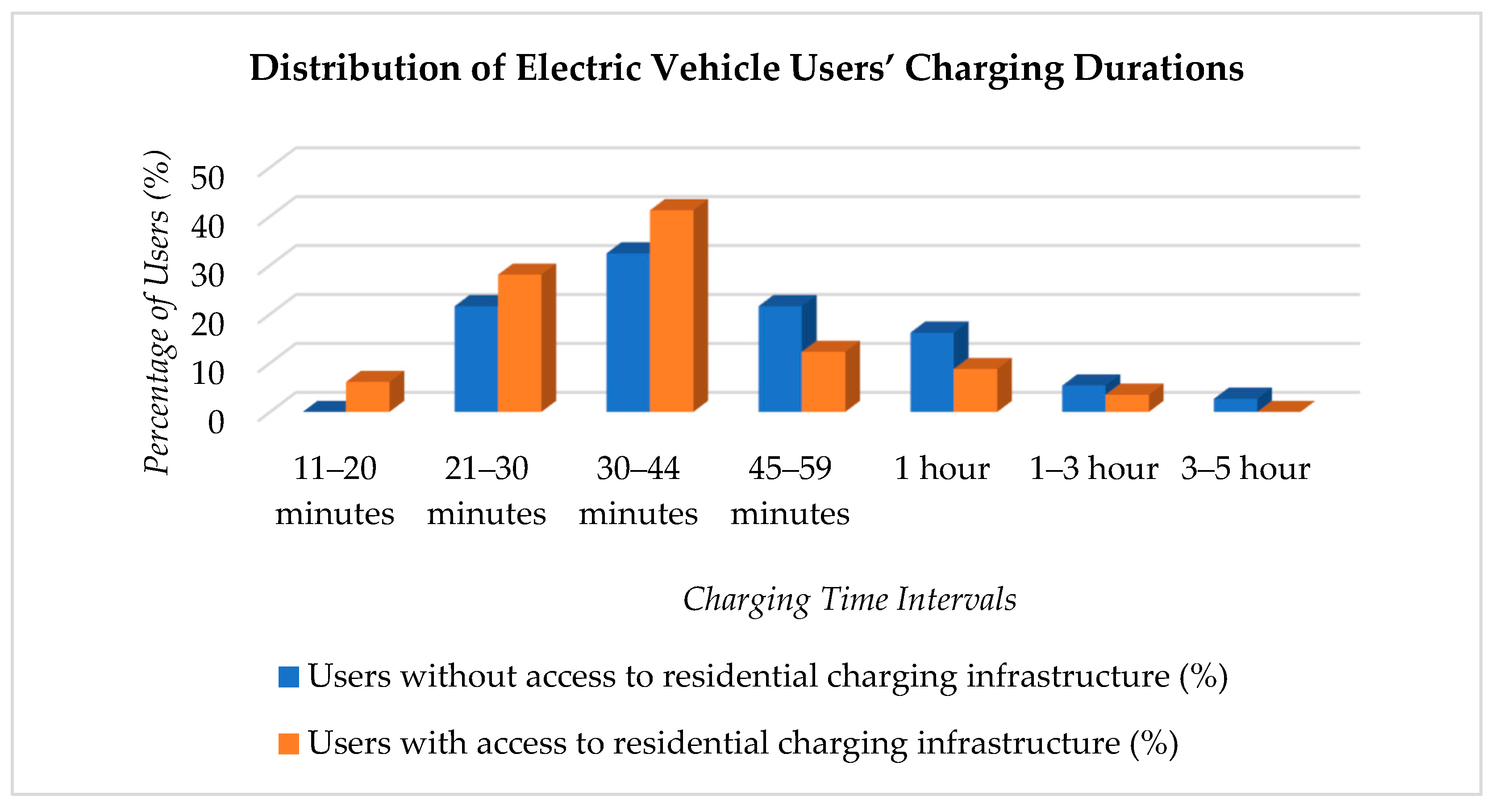

4.2. User Preferences, Charging Behaviors, and EV Adoption Tendencies

4.3. Baseline Assessment of Current Pump Utilization Profile and EV Integration

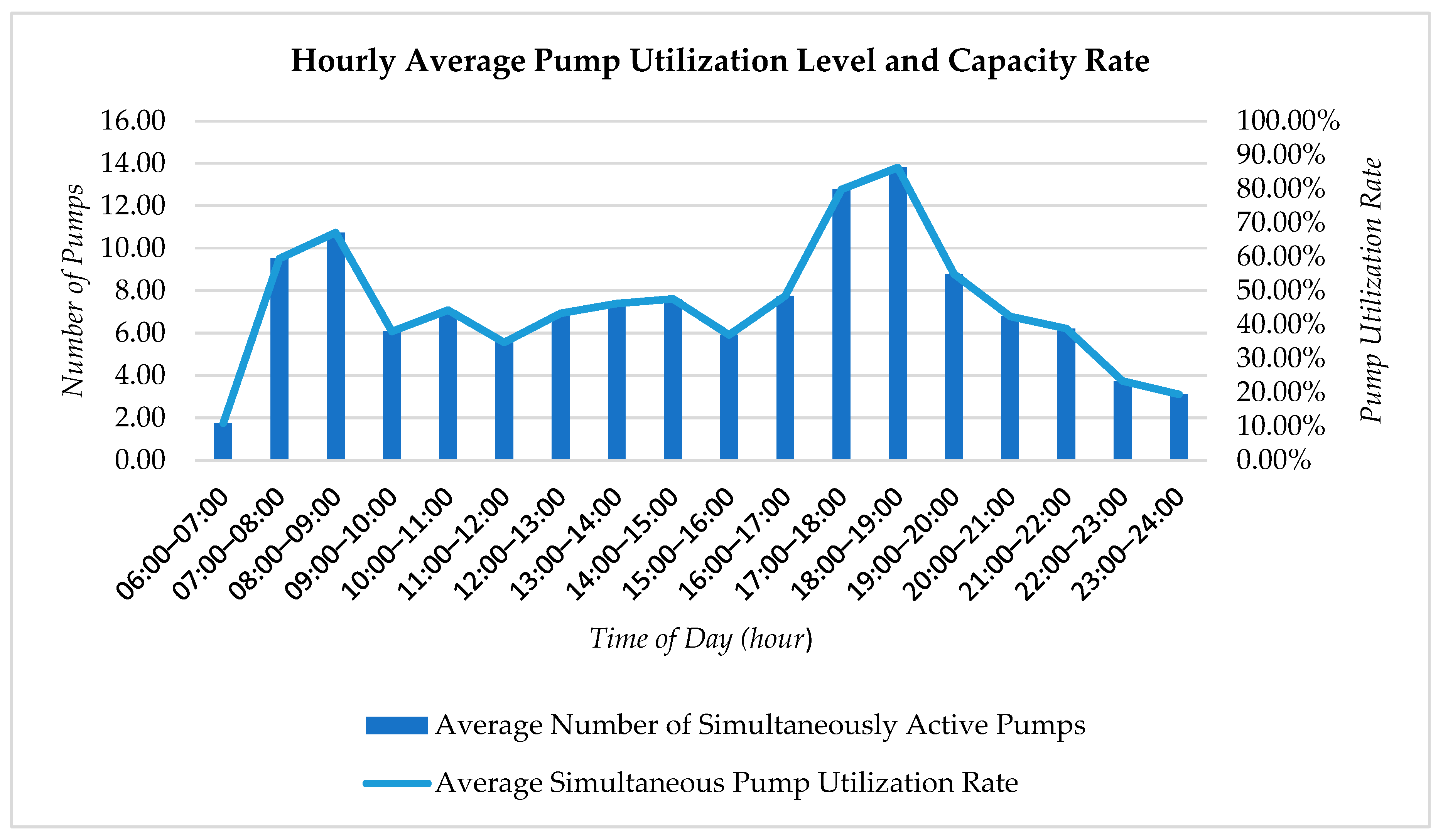

4.3.1. Current Fuel Pump Utilization Profile and Fundamental Assessment for EV Integration

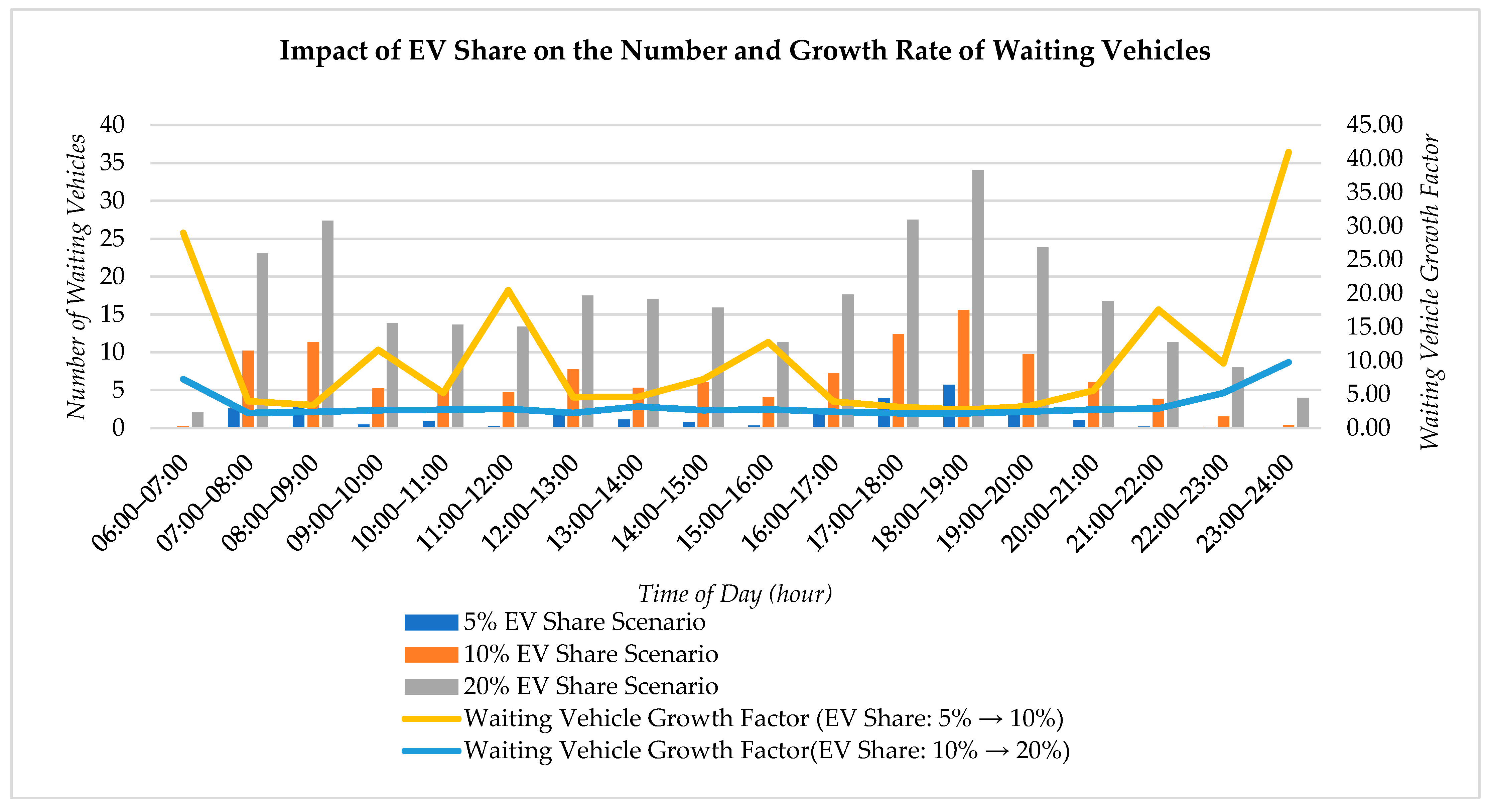

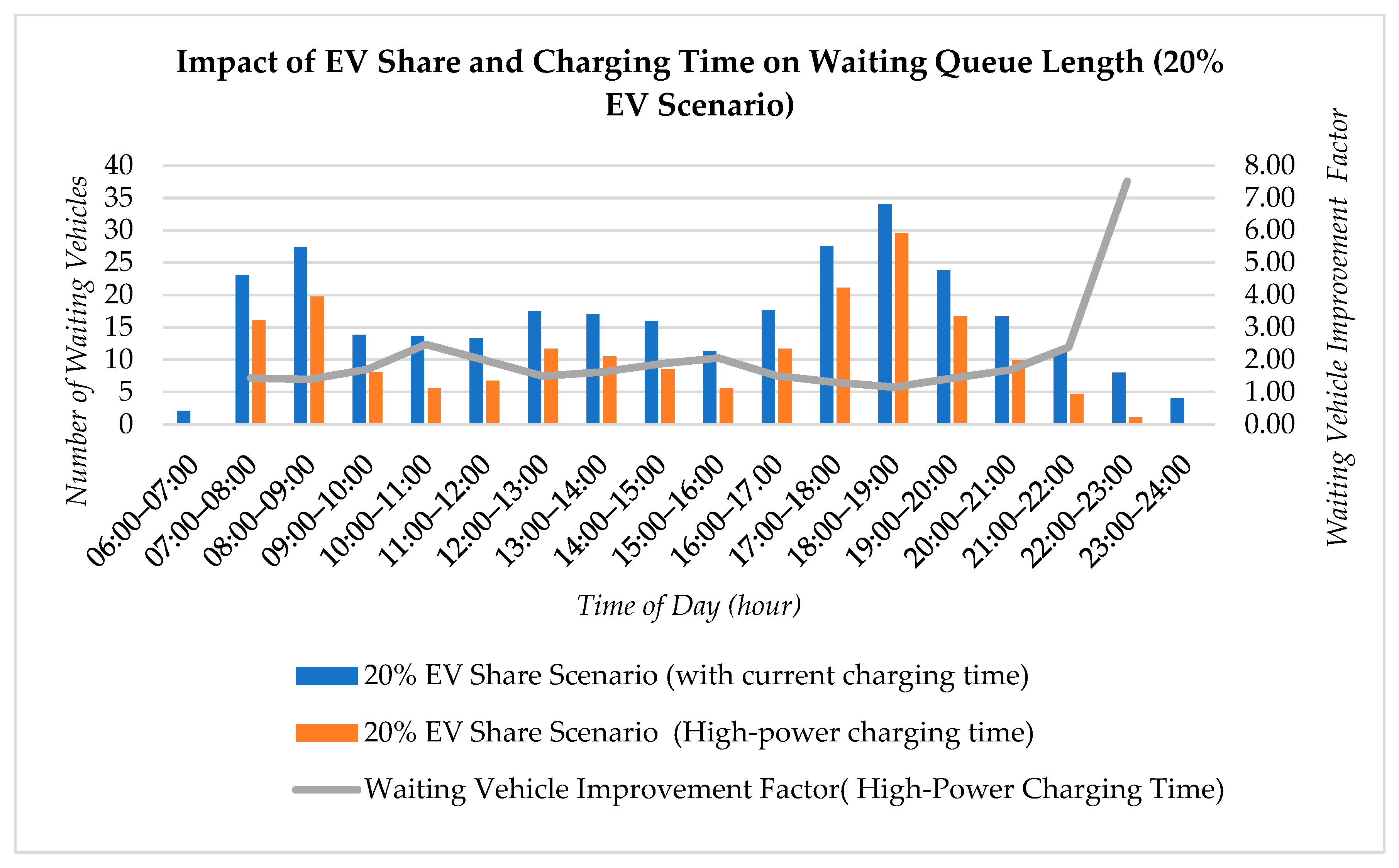

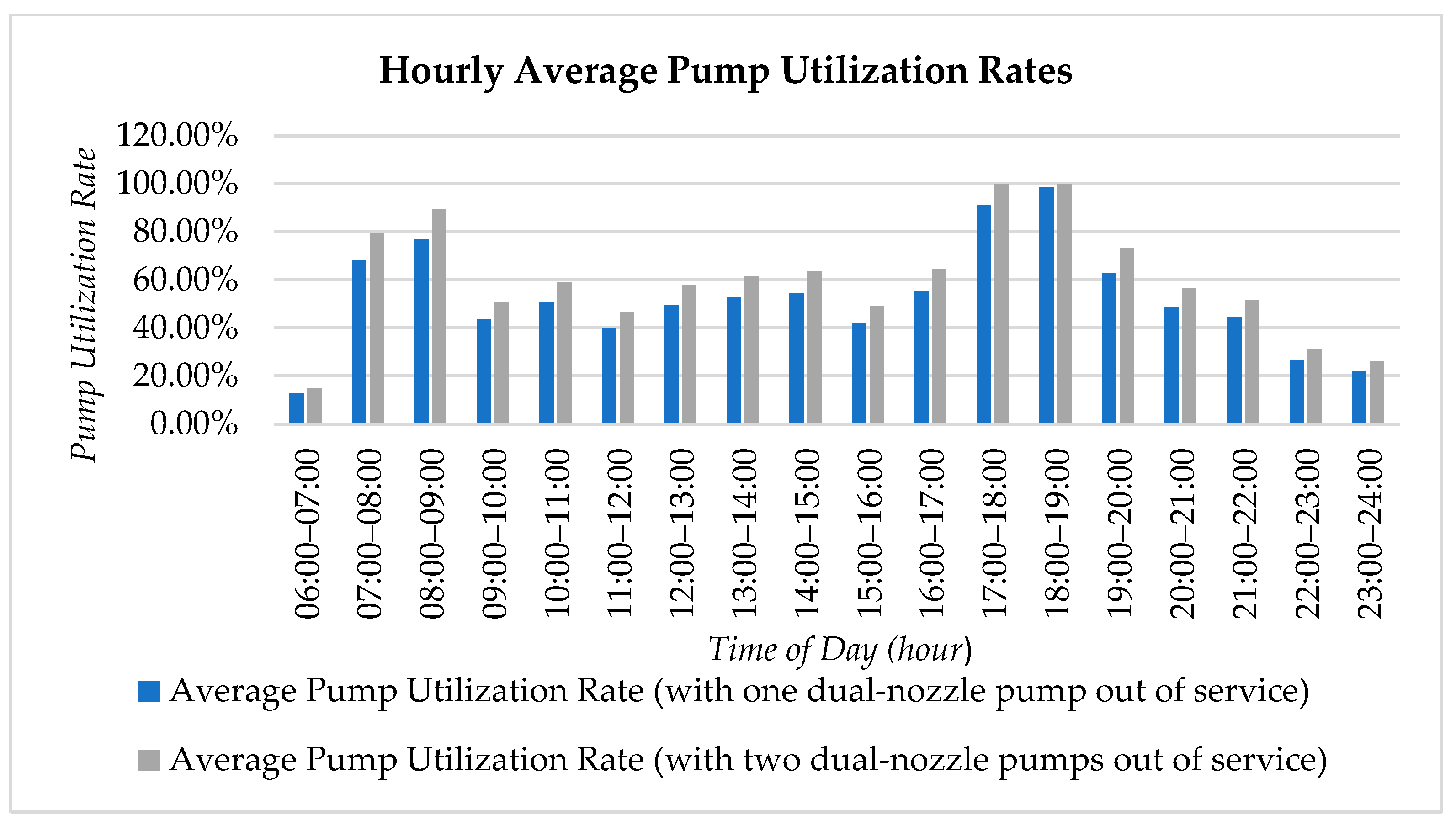

4.3.2. Analysis of EV Percentage-Change Scenarios and Vehicle Waiting Queues

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| ICEV | Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle |

| DC | Direct Current |

| EMRA | Energy Market Regulatory Authority |

| K–S Test | Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit test |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| GF | Growth Factor |

| IF | Improvement Factor |

References

- Raihan, A.; Rashid, M.; Voumik, L.C.; Akter, S.; Esquivias, M.A. The dynamic impacts of economic growth, financial globalization, fossil fuel, renewable energy, and urbanization on load capacity factor in Mexico. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.; Lau, K.; Li, Y.; Poon, C.; Wu, Y.; Chu, P.K.; Luo, Y. Commercialization of electric vehicles in Hong Kong. Energies 2022, 15, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Transport; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025; Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-transport (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- TrendForce. Global Public EV Charging Piles Growth to Slow Significantly in 2024, Led by China and South Korea, Says TrendForce. Available online: https://www.trendforce.com/presscenter/news/20241120-12370.html (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Macioszek, E. The role of incentive programs in promoting the purchase of electric cars—Review of good practices and promoting methods from the world. In Research Methods in Modern Urban Transportation Systems and Networks; Macioszek, E., Sierpiński, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, M.M.; Saleh, S.M.; Samy, M.M.; Barakat, S. Optimizing grid-tied hybrid renewable systems for EV charging in Egypt: A techno-economic analysis. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladigbolu, J.; Bakare, M.S.; Motlagh, S.G.; Mujeeb, A.; Li, L. A review on transport and power systems planning-operation integrating electric vehicles, energy storage, and other distributed energy resources. J. Energy Storage 2025, 135, 118419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, N.K.; Sabhahit, J.N.; Jadoun, V.K.; Pandey, A.K.; Rao, V.S.; Saraswat, A.A. Grid-interfaced DC microgrid-enabled charging infrastructure for empowering smart sustainable cities and its impacts on the electrical network: An inclusive review. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capar, I.; Kuby, M.; Leon, V.J.; Tsai, Y.-J. An arc cover–path-cover formulation and strategic analysis of alternative-fuel station locations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 227, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, T.; Devabalaji, R.K.; Kumar, J.A.; Thanikanti, S.B.; Nwulu, N.I. A comprehensive review and analysis of the allocation of electric vehicle charging stations in distribution networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 5404–5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daşcıoğlu, B.G.; Tuzkaya, G.; Kılıç, H.S. A model for determining the locations of electric vehicles’ charging stations in Istanbul. Pamukkale Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 25, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamova, V.; Popov, S.; Baeva, S.; Hinov, N. Design scenarios and risk-aware performance framework for modular EV fast charging stations. Energies 2025, 18, 6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangini, A.M.; Fanti, M.P.; Silvestri, B.; Ranieri, L.; Roccotelli, M. Modeling and simulation of electric vehicles charging services by a time colored Petri net framework. Energies 2025, 18, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevin, A.; Yaman, G.; Atılgan, D. Analysis of queue models in simulation applications. Sak. Univ. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2025, 8, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Bhagavathy, S.M.; Thakur, J. Accelerating electric vehicle adoption: Techno-economic assessment to modify existing fuel stations with fast charging infrastructure. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 3033–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, D.; Majhi, B.K.; Dutta, A.; Mandal, R.; Jash, T. Study on possible economic and environmental impacts of electric vehicle infrastructure in public road transport in Kolkata. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2015, 17, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, G.; Torres, J.; Cervero, D.; García, E.; Alonso, M.Á.; Almajano, J. EV charging infrastructure in a petrol station: Lessons learned. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (INDEL), Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1–3 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, I.S.; Zafar, U.; Bayhan, S. Could petrol stations play a key role in transportation electrification? A GIS-based coverage maximization of fast EV chargers in urban environment. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 18789–18802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arup; National University of Singapore (NUS). The Future of Petrol Stations in an Electric Vehicle World; Arup: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.D. The Future of Gas Stations: Converting to EV Charging Stations? Carscoops. 8 April 2023. Available online: https://www.carscoops.com/2023/04/gas-stations-to-turn-into-charge-ports-suggests-new-study (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2025: Prospecting the Transition to 2035; IEA: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Energy Market Regulatory Authority (EMRA). Turkey Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Report; Energy Market Regulatory Authority: Ankara, Turkey, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Anadolu Agency (AA). Gasoline and Diesel Car Sales Decline While Electric and Hybrid Sales Continue to Rise; Anadolu Agency (AA): Çankaya, Turkey, 2025; Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/benzinli-ve-dizel-otomobil-satislari-duserken-elektrikliyle-hibritte-yukselis-suruyor/3706357 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Mohammed, A.; Saif, O.; Abo-Adma, M.; Fahmy, A.; Elazab, R. Strategies and sustainability in fast charging station deployment for electric vehicles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, S. Integrated Planning of Residential and Commercial Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure: A Strategic Bi-Level Optimization and Queuing Framework Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Energy Market Regulatory Authority (EMRA). Petroleum Market License Statistics; Energy Market Regulatory Authority: Çankaya, Turkey, 2025. Available online: https://lisans.epdk.gov.tr/epvys-web/faces/pages/lisans/petrolIstatistik/petrolIstatistik.xhtml (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Azin, B.; Yang, X.; Marković, N.; Liu, M. Infrastructure enabled and electrified automation: Charging facility planning for cleaner smart mobility. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 101, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, U.; Kalam, A.; Shi, J. Smart control of BESS in PV integrated EV charging station for reducing transformer overloading and providing battery-to-grid service. J. Energy Storage 2020, 28, 101224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Ilka, R.; He, J.; Liao, Y.; Cramer, A.M.; Mccann, J.; Delay, S.; Coley, S.; Geraghty, M.; Dahal, S. Impact of electric vehicle charging on power distribution systems: A case study of the grid in Western Kentucky. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 49002–49023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, O.; Binding, C. Planning electric-drive vehicle charging under constrained grid conditions. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Power System Technology, Hangzhou, China, 24–28 October 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xu, Z.; Wen, F.; Wong, K.P. Traffic-constrained multiobjective planning of electric-vehicle charging stations. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2013, 28, 2363–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaimeh, M.; Salisbury, S.D.; Hill, G.A.; Blythe, P.T.; Scoffield, D.R.; Francfort, J.E. Analysing the usage and evidencing the importance of fast chargers for the adoption of battery electric vehicles. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figenbaum, E.; Kolbenstvedt, M. Learning from Norwegian Battery Electric and Plug-in Hybrid Vehicle Users—Results from a Survey of Vehicle Owners; Institute of Transport Economics Norwegian Centre for Transport Research: Oslo, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.E.; Recker, W. Strategic hydrogen refueling station locations with scheduling and routing considerations of individual vehicles. Transp. Sci. 2015, 49, 767–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayri, A.; Ma, X. Grid impacts of electric vehicle charging: A review of challenges and mitigation strategies. Energies 2025, 18, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMonaca, S.; Ryan, L. The state of play in electric vehicle charging services—A review of infrastructure provision, players, and policies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xylia, M.; Olsson, E.; Macura, B.; Nykvist, B. Estimating charging infrastructure demand for electric vehicles: A systematic review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 59, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. The Future of EV Charging Infrastructure; McKinsey: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Beefull. Will Charging My Electric Car at Home Become More Expensive? What Does EMRA’s Last Resort Supply Tariff (LRST) Regulation Bring? Available online: https://beefull.com/blog/elektrikli-aracimi-evden-sarj-etmek-artik-daha-mi-pahali-olacak-epdknin-sktt-duzenlemesi-ne-getiriyor (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Gönül, Ö.; Duman, A.C.; Güler, Ö. A comprehensive framework for electric vehicle charging station siting along highways using weighted sum method. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Industry and Technology. Mobility Vehicles and Technologies Roadmap (2022–2030); Republic of Turkey Ministry of Industry and Technology: Ankara, Turkey, 2022. Available online: https://www.sanayi.gov.tr/assets/pdf/plan-program/MobiliteAracveTeknolojileriYolHaritasi.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Smappee. AC vs. DC EV Charging: What’s the Difference and Why It Matters. Smappee. 1 December 2025. Available online: https://www.smappee.com/blog/ac-vs-dc-ev-charging/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- ChargeLab. 86% of EV Drivers can Charge at Home, But over Half Still Rely on Public Chargers, ChargeLab Survey Finds; PR Newswire: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, I.; Medha, M.B.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Global challenges of electric vehicle charging systems and its future prospects: A review. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2023, 49, 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facilities Managers Federation (TEYFED). Risks of Charging Infrastructure for Electric Vehicles; TEYFED: Tuzla, Turkey, 2024; Available online: https://teyfed.org/elektrikli-araclarda-sarj-altyapisi-riskleri/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Araujo, A.; Araujo, D.; Vasconcelos, A.; Rosas, P.; Medeiros, L.; Conceicao, J. A proposal for technical and economic sizing of energy storage system and PV for EV charger stations with reduced impacts on the distribution network. In Proceedings of the CIRED 2021 Conference, Online, 20–23 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muzir, N.A.Q.; Mojumder, M.R.H.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Selvaraj, J. Challenges of electric vehicles and their prospects in Malaysia: A comprehensive review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walford, L. EV, Battery & Charging News: Drivers Willing to Pay Extra for Fast Chargers. Auto Connected Car News (Press Coverage by Next10). 15 September 2024. Available online: https://www.next10.org/press-coverages/ev-battery-charging-news-drivers-willing-pay-extra-fast-chargers (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Hecht, C.; Figgener, J.; Sauer, D.U. Analysis of electric vehicle charging station usage and profitability in Germany based on empirical data. iScience 2022, 25, 105634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.H.; Romli, M.I.F.; Abd Rahim, R.; Aziz, M.E.A.; Abd Rahman, D.H.; Mokhtaruddin, H.H. Development of an advanced current mode charging control strategy system for electric vehicle batteries. Int. J. Power Electron. Drive Syst. (IJPEDS) 2024, 15, 2639–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erce, M.I.; Dönmez, B.B.; Sanlı, Y.B.; Güven, E.; Eren, T. Charging station location selection for electric vehicles. Bursa Uludag Univ. J. Sci. 2025, 12, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbahar, I.T.; Sutcu, M.; Almomany, A.; Ibrahim, B.S.K.K. Optimizing electric vehicle charging station location on highways: A decision model for meeting intercity travel demand. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Office of Energy and Transportation. Public EV Charging Station Site Selection Checklist. DriveElectric.gov; 2023. Available online: https://driveelectric.gov/files/ev-site-selection.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Kok, N.; Monkkonen, P.; Quigley, J.M. Land use regulations and the value of land and housing: An intra-metropolitan analysis. J. Urban Econ. 2014, 81, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsun, O.; Lanets, O.; Solodkyy, S. Impact of street parking on delays and the average speed of traffic flow. Transp. Technol. 2020, 1, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.; Kumar, A. Critical analysis of road side friction on an urban arterial road. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2023, 13, 10261–10269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrenacci, N.; Valentini, M.P. A literature review on the charging behaviour of private electric vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albatayneh, A.; Juaidi, A.; Abdallah, R.; Jeguirim, M. Preparing for the EV revolution: Petrol stations profitability in Jordan. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 79, 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time Interval | Sample Size (n) | Suitable Probability Distribution for Interarrival Times (s) | Squared Error | K–S Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 06:00–07:00 | 31 | 27 + WEIB (80.9, 1.27) | 0.0583510 | 0.131 | 0.0901 |

| 08:00–09:00 | 152 | 0.999 + WEIB (23, 1.02) | 0.0082360 | 0.101 | 0.0867 |

| 10:00–11:00 | 91 | 57 + 483 × BETA (1.6, 2.29) | 0.0046400 | 0.0503 | >0.15 |

| 11:00–12:00 | 87 | NORM (39.5, 23.7) | 0.0308540 | 0.164 | 0.0647 |

| 14:00–15:00 | 96 | NORM (246, 70.6) | 0.0408520 | 0.143 | 0.0478 |

| 17:00–18:00 | 159 | 6 + 116 × BETA (1.44, 2.66) | 0.0321930 | 0.0107 | >0.15 |

| 18:00–19:00 | 201 | −0.5 + GAMM (13.6, 1.34) | 0.0015855 | 0.104 | >0.15 |

| 19:00–20:00 | 137 | 5.5 + WEIB (21.1, 1.27) | 0.0038800 | 0.0686 | >0.15 |

| 22:00–23:00 | 58 | TRIA (4, 56.5, 109) | 0.0075770 | 0.112 | >0.15 |

| 23:00–24:00 | 38 | 43.5 + 96 × BETA (1.06, 0.807) | 0.0322550 | 0.117 | >0.15 |

| Time Interval | Sample Size (n) | Suitable Probability Distribution for Dwell Time (s) | Squared Error | K–S Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 06:00–07:00 | 31 | 129 + EXPO (75.5) | 0.0259310 | 0.134 | 0.119 |

| 08:00–09:00 | 152 | 150 + 398 × BETA (0.883, 2.48) | 0.0447860 | 0.11 | >0.15 |

| 10:00–11:00 | 91 | 91 + GAMM (139, 1.36) | 0.0093630 | 0.104 | 0.0601 |

| 11:00–12:00 | 87 | NORM (44.3, 23.8) | 0.0417880 | 0.15 | 0.0485 |

| 14:00–15:00 | 96 | 81 + WEIB (159, 1.64) | 0.0203620 | 0.115 | 0.0963 |

| 17:00–18:00 | 159 | 102 + WEIB (163, 1.77) | 0.0411910 | 0.139 | 0.082 |

| 18:00–19:00 | 201 | 102 + ERLA (48.4, 3) | 0.0155760 | 0.0752 | >0.15 |

| 19:00–20:00 | 137 | 78 + WEIB (169, 1.69) | 0.0080300 | 0.0894 | 0.149 |

| 22:00–23:00 | 58 | 86 + ERLA (73, 2) | 0.0058520 | 0.0629 | > 0.15 |

| 23:00–24:00 | 38 | TRIA (56, 361, 478) | 0.0137530 | 0.11 | 0.0472 |

| Year | Low Scenario | Medium Scenario | High Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 202,030 | 269,154 | 361,893 |

| 2030 | 776,362 | 1,321,932 | 1,679,600 |

| 2035 | 1,779,488 | 3,307,577 | 4,214,273 |

| Year | Total Vehicles (Million) | EVs (Million) | EV Share (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2030 | 41.2 | 2.7 | 6.6% |

| 2035 | 42.2 | 4.2 | 10.0% |

| 2040 | 43.2 | 7.2 | 17.0 |

| Time Interval | Field Vehicle Arrivals | 95% CI—Model Vehicle Arrivals | Field Dwell Time (s) | SD | 95% CI—Model Dwell Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 06:00–07:00 | 31 | 204.5 | 94.6 | ||

| 07:00–08:00 | 134 | 33 | 255.6 | 107.1 | 4.98 |

| 08:00–09:00 | 152 | 18 | 254.3 | 83.8 | 249.3 |

| 12:00–13:00 | 112 | 85 | 224.5 | 86.3 | |

| 13:00–14:00 | 106 | 251.1 | 90.5 | 41 | |

| 15:00–16:00 | 81 | 262.8 | 92.2 | 48 | |

| 19:00–20:00 | 137 | 230.7 | 88.6 | ||

| 20:00–21:00 | 103 | 237.3 | 92.2 | 4.33 | |

| 23:00–24:00 | 38 | 294.3 | 87.0 | 33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yetimoğlu, M.; Karaşahin, M.; Yıldırım, M.S. The Impact of Electric Charging Unit Conversion on the Performance of Fuel Stations Located in Urban Areas: A Sustainable Approach. Sustainability 2026, 18, 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020893

Yetimoğlu M, Karaşahin M, Yıldırım MS. The Impact of Electric Charging Unit Conversion on the Performance of Fuel Stations Located in Urban Areas: A Sustainable Approach. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020893

Chicago/Turabian StyleYetimoğlu, Merve, Mustafa Karaşahin, and Mehmet Sinan Yıldırım. 2026. "The Impact of Electric Charging Unit Conversion on the Performance of Fuel Stations Located in Urban Areas: A Sustainable Approach" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020893

APA StyleYetimoğlu, M., Karaşahin, M., & Yıldırım, M. S. (2026). The Impact of Electric Charging Unit Conversion on the Performance of Fuel Stations Located in Urban Areas: A Sustainable Approach. Sustainability, 18(2), 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020893