1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization and unregulated development have caused severe landscape degradation across the entire territory of South Korea. Landscape deterioration has emerged as a global environmental and social issue [

1,

2,

3,

4], prompting growing interest in the application of landscape planning and modeling approaches as potential solutions [

5,

6,

7].

Landscape planning can be defined as a spatial planning concept that reflects the results of basic investigations, analyses, and evaluation maps for the various functions of landscape resources—such as conservation, recreation and nature experience, and aesthetic or visual aspects—into the actual spatial planning process, thereby guiding the national territory toward environmentally and visually harmonious development [

8]. In other words, environmental planning does not view the national space merely from an aesthetic or visual perspective, but rather seeks to establish plans from a comprehensive and integrative standpoint [

9]. To establish such comprehensive landscape planning, systematic organization and the application of planning models are essential prerequisites, since landscape planning models serve as key tools for resolving problems such as landscape degradation and habitat destruction arising from various scales of development—ranging from district-level to regional, urban, and rural areas [

10].

As interest in landscape planning has grown, both domestic and international studies have increasingly addressed this topic. These studies can be categorized into three main thematic areas, the relationship between legal frameworks and landscape planning, the connection between landscape planning and related development projects, and the applicability of landscape planning models.

Regarding the first category, several studies examined the linkage between legislation and landscape planning [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Kim et al. [

11] compared and analyzed the current legal systems and prior studies on landscape planning, proposing institutional improvements for effectively conserving natural landscape elements from development impacts. Similar findings were reported by Song et al. [

13]

The second category concerns studies on landscape-related projects [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. For instance, Lee and Cho [

18] argued for the establishment of a comprehensive landscape planning system within the Landscape Act to strengthen the independent status of rural landscape planning and sought ways to integrate planning and implementation within rural development projects.

The third category addresses the applicability of landscape planning models [

10,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Ko et al. [

22] analyzed the developmental trends and typological criteria of forest landscape models, summarized their characteristics, and proposed directions for future improvement.

Despite these ongoing efforts, several research gaps persist. First, in the context of Republic of Korea, while various levels of landscape management—including landscape planning, urban landscape planning, and forest maintenance planning—are currently being implemented, the management systems predominantly target small-scale areas. These efforts tend to focus on aesthetic and visual improvements in urban environments rather than addressing forest or rural landscapes. Furthermore, discrepancies in the perception of ‘landscape’ among local governments have led to a lack of broad-scale landscape management guidelines, such as those at the provincial (Do) level. Consequently, this hinders the generalization and popularization of landscape management in Republic of Korea.

From an academic perspective, studies examining the relationship between legal frameworks and planning often remain declarative, emphasizing the direction of institutional reform rather than proposing detailed operational frameworks. Similarly, research on landscape projects frequently addresses individual improvements without sufficiently examining the systemic interconnection between landscape planning and broader project ecosystems. Moreover, efforts toward concrete systematization and modeling remain limited. In the case of landscape planning models, practical applications to real-world scenarios are scarce; where they exist, they are often restricted to specific sites rather than encompassing urban or district-level scales. Consequently, despite continuous research efforts, comprehensive integration among legislation, landscape planning, and related implementation projects remains insufficient.

Recently, digital twin technology has emerged as a practical solution for addressing landscape degradation. A digital twin is defined as a technology that precisely represents the physical environment in a virtual space, enabling the simulation and prediction of future real-world states based on this digital representation [

25].

Relevant studies [

26,

27] have examined international cases—in locations such as Helsinki, Singapore, and New South Wales—and proposed potential applications for the Republic of Korea, including construction and redevelopment simulations, unmanned mobility safety modeling, and wildfire response via forest road twins [

28]. However, the majority of this research remains limited to a conceptual level, focusing primarily on the necessity and direction of development. Spatially, digital twin implementation has been concentrated in major metropolitan areas like Seoul and Daegu. Furthermore, its practical utility has been largely confined to general mapping or urban surveys, rather than planning-oriented applications such as landscape planning.

Therefore, this study differentiates itself from existing advanced international cases (e.g., Singapore, Helsinki), which predominantly focus on the precise reproduction of physical environments, facility maintenance, or microclimate analysis. Instead, this research integrates fragmented Korean landscape regulations and planning elements into the digital twin environment through text mining. This approach moves beyond simple ‘visualization’ to function as a ‘legal and administrative decision-support system’ that projects complex regulations onto physical space, thereby eliminating uncertainty in the planning phase. Additionally, by utilizing Blender and OpenStreetMap (OSM) instead of expensive commercial software, this study presents a universal and scalable methodology.

Ultimately, this study aims to establish an implementation-oriented ‘comprehensive framework’ by systematically restructuring the landscape planning model and to demonstrate its practical utility by integrating it with digital twin technology.

To achieve this, the research process began by laying a theoretical foundation through the reconfiguration of models from prior studies to reflect contemporary planning contexts, followed by the identification of direct linkages between existing legal systems, statutory plans, and implementation projects. In particular, an integrated ‘Landscape Planning Platform’ was constructed through the modularization of planning terms derived via text mining and the refinement of statutory guidelines. Finally, by implementing this platform within a digital twin environment to generate a ‘Digital Twin Landscape Planning Map,’ the study empirically verified the procedural visualization of the landscape planning process and its potential for practical adoption.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Concept of Landscape Planning

Landscape is a complex entity capable of multiple interpretations. Landscape ecology is the study of the spatial structure, function, and changes of landscapes, i.e., the complex interaction system among geoecological, bioecological, and humanistic elements inherent in complex landscapes. Landscape planning is a spatial planning tool, particularly for guiding national spatial planning in a natural environment and landscape-friendly manner, based on the concepts of landscape and landscape ecology. However, the concept of landscape planning, which is just as diverse as the concepts of landscape and landscape ecology, also varies across countries, regions, academic fields, and experts. Rookwood [

29], Heiland [

30], Natuhara [

31], Potschin & Haines-Young [

32], Heiland et al. [

33] and Oeckinger et al. [

34] emphasize the establishment of environmentally sustainable landscape plans based on ecological analysis data such as habitats, biodiversity, landscape mosaic transformation, and climate. In contrast, Larsen & Harlan [

35], Oku & Fukamachi [

36], Barroso et al. [

37], and Howley et al. [

38] emphasize the importance of landscape planning based on human psychological behavior, such as visitors’ landscape perception, natural recreational activities, and landscape preference analysis through questionnaires. Nevertheless, many landscape planning experts today are breaking away from the perspective of a single specialty and emphasizing the concept of a new landscape planning strategy based on a holistic approach. For example, Hersperger [

39] have emphasized the need to solve landscape problems arising on a wide scale through landscape planning based on a holistic approach that encompasses ecological and humanistic aspects. In summary, landscape planning encompasses not only ecological and landscape conservation, but also diverse aspects such as recreation, aesthetics, nature experiences, and eco-friendly development to enhance the quality of life. It can be understood as a spatial planning system applicable nationwide.

To systematically implement this, the use of a landscape planning model was deemed crucial. A landscape planning model can be defined as an objective planning system that implements landscape planning based on landscape ecological theory and principles [

10]. This study restructured the landscape planning model and established a platform for nationwide application. Establishing a landscape planning model platform is expected to increase accessibility to landscape planning, enabling planning to be implemented across a wide range of sites, from small to large.

2.2. Concept of Digital Twin

The concept of the digital twin originates from industrial engineering and refers to a digital replica of physical assets, processes, or environments that enables real-time monitoring and simulation. It allows planners to visualize the dynamic interactions between environmental, infrastructural, and social systems.

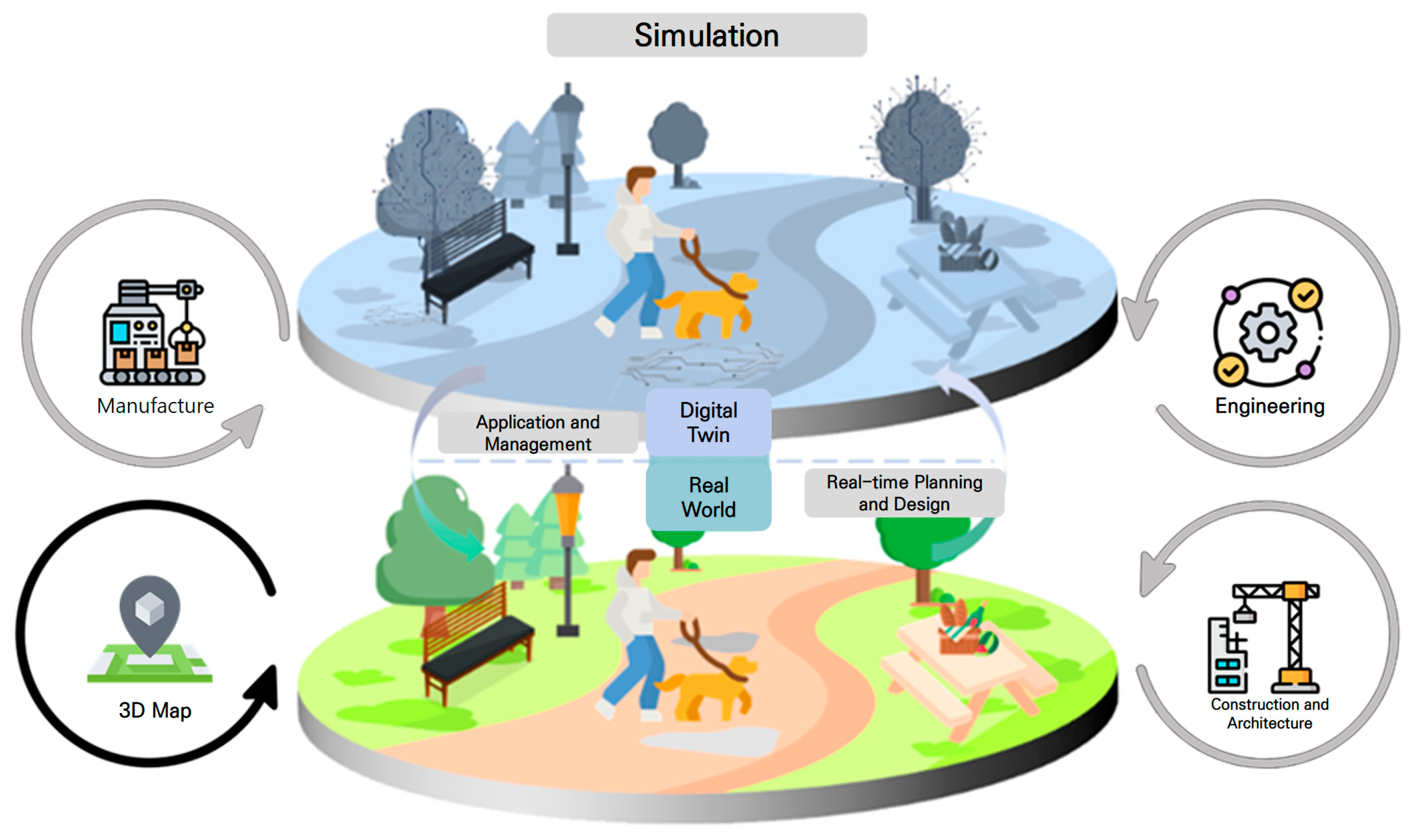

A digital twin comprises three core components: (1) a physical entity, (2) a virtual model, and (3) data connectivity between them [

28]. Through real-time feedback loops, it simulates spatial changes, predicts system behavior, and supports decision-making under various scenarios (

Figure 1).

In the field of spatial planning, the digital twin serves as a data-driven planning tool that enhances transparency and interactivity. In Republic of Korea, it has been applied in limited contexts, such as Seoul’s “S-Map,” LX’s “3D National Spatial Information Platform,” and disaster management systems. However, its application to landscape planning remains underdeveloped.

As digital twin technology matures, its role in managing ecological networks, monitoring visual corridors, and forecasting urban expansion is expected to become increasingly significant.

2.3. Integration of Landscape Planning and Digital Twin

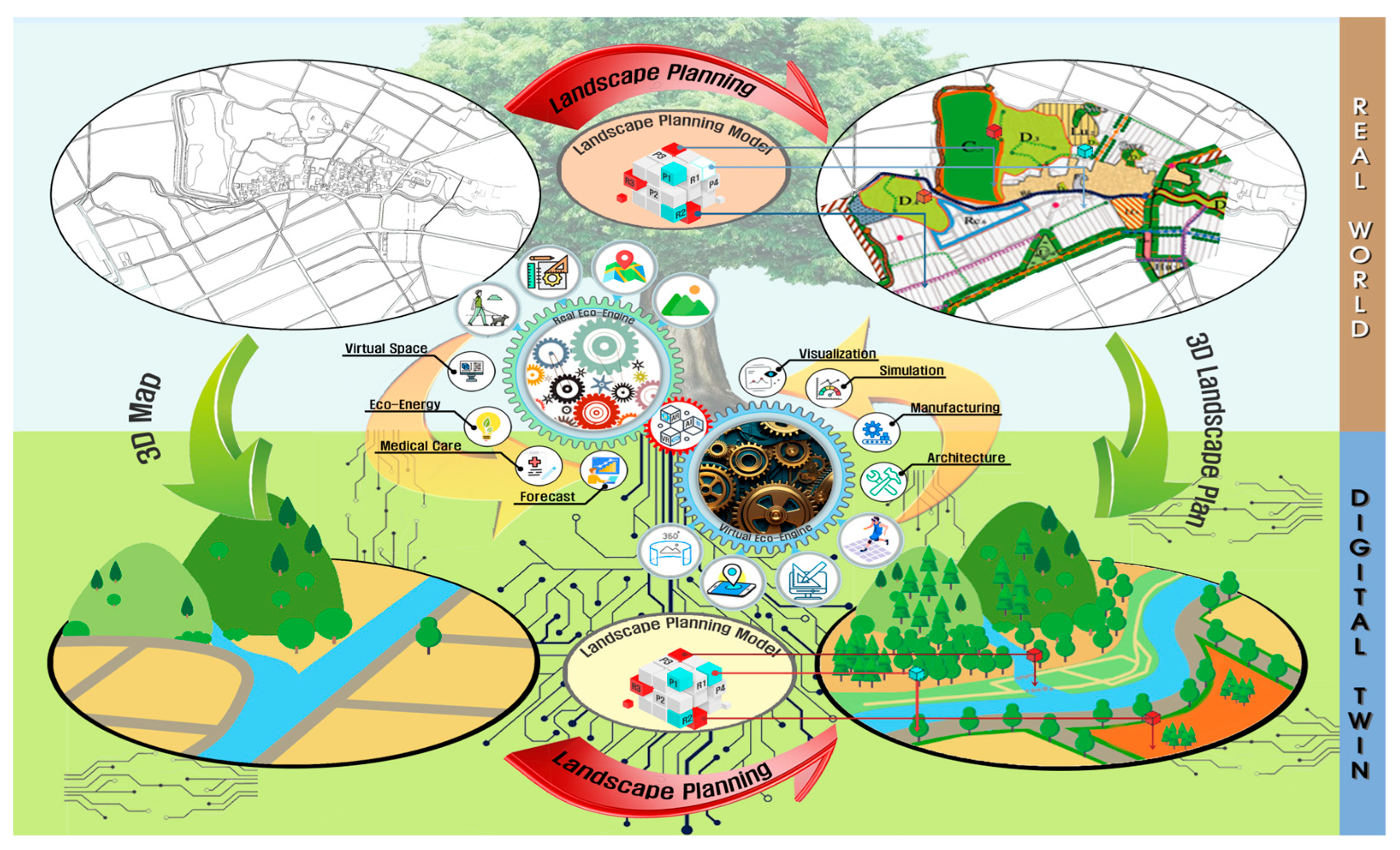

The integration of digital twin technology into landscape planning provides new possibilities for dynamic visualization, participatory design, and adaptive management. Both systems share fundamental characteristics—spatial data dependency, scenario-based simulation, and iterative planning processes.

By embedding a landscape planning model within a digital twin framework, planners can simulate land-use changes, visualize aesthetic outcomes, and evaluate the ecological impact of design alternatives. This process also facilitates communication among policymakers, experts, and local residents by providing an interactive, visually intuitive platform.

From a governance perspective, digital twins can act as bridging tools linking top-down statutory plans with bottom-up community initiatives. They allow continuous monitoring of landscape transformations and feedback-based policy adjustments, thereby creating a feedback loop between planning and implementation (

Figure 2).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Scope

The scope of this study is confined to redefining the landscape planning model and deriving relevant legal frameworks, projects, and planning components necessary for establishing a comprehensive landscape planning platform. In particular, the redefinition of the landscape planning model focuses on the ecological, nature-experience, and recreational aspects of landscape planning. This approach seeks to complement the current emphasis on aesthetic and visual dimensions that has dominated landscape planning practices in Republic of Korea. Furthermore, projects that do not produce tangible physical outcomes were excluded from the analysis, as it is difficult to establish meaningful linkages between such projects and landscape planning processes.

3.2. Research Framework

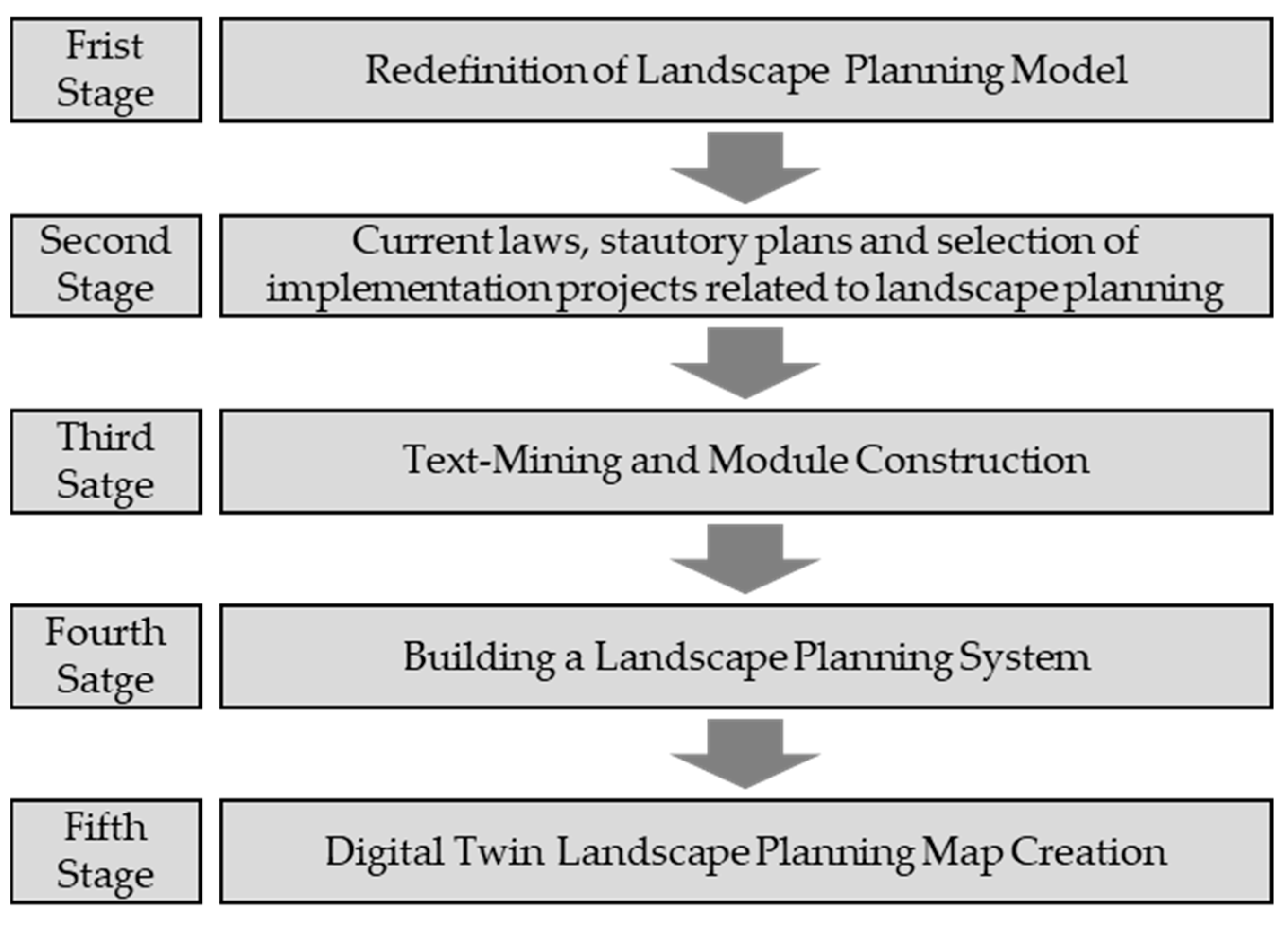

The research procedure of this study consists of five main stages. In the first stage (

Figure 3), two types of previously developed landscape planning models [

10] were reorganized and restructured to reflect current circumstances and contemporary planning contexts. In the second stage, in order to identify the direct linkages between the landscape planning model, existing legal frameworks, statutory plans, and implementation projects, laws, plans, and projects related to landscape management were systematically extracted and analyzed. This process involved visual representation through the designation of colors and patterns by government agencies, analysis of landscape change rates, and application of modular visualization techniques. In the third stage, text-mining analysis was conducted to extract frequently occurring and recurrent terms associated with landscape planning, which were subsequently modularized. In this stage, the detailed guidelines of statutory plans were compared with the proposed modules to identify areas for refinement, supplementation, and expansion. In the fourth stage, the reconstructed landscape planning model, related laws, plans, projects, and planning modules were integrated to establish a comprehensive “Landscape Planning Platform”. Finally, in the fifth stage, the developed landscape planning platform was combined with digital twin technology to produce a “Digital Twin Landscape Planning Map”, enabling the procedural visualization of the landscape planning process.

3.3. Redefinition of the Landscape Planning Model

In order to effectively link the landscape planning model with legal frameworks, planning systems, and implementation projects, it was deemed necessary to integrate the existing models into a unified framework and to redefine their detailed indicators. The conventional landscape planning models are categorized into two domains: one focusing on the conservation aspect and the other emphasizing the nature-experience and recreational aspect [

10]. In this study, both models were reconfigured and subsequently merged into a single integrated planning model. Through this process, a restructured landscape planning model was developed that harmonizes the conservation-oriented and the experiential–recreational dimensions within one cohesive planning framework.

3.4. Current Laws, Statutory Plans, and Selection of Implementation Projects Related to Landscape Planning

To explore strategies for establishing a systematic landscape planning platform, it was first necessary to analyze the current landscape planning framework in the Republic of Korea. For this purpose, existing national laws related to landscape management were examined in detail. Among these, the National Land Planning and Utilization Act was identified as a primary legal foundation, as it serves as the fundamental statute that must be consulted when planning or designing the national territory. This Act encompasses key planning instruments closely related to landscape planning, including the National Land Plan, Metropolitan Urban Plan, Urban and County Basic Plan, and District Unit Plan, thereby establishing an essential linkage with landscape policy and practice. Based on the selected legal frameworks, statutory plans were extracted primarily from those implemented under the identified laws. Furthermore, implementation projects were derived to assess the feasibility of applying the landscape planning model in practice. These projects were identified through a comprehensive review of relevant agencies, including local governments and public institutions responsible for project execution. This approach enabled the identification of actionable connections between legal systems, statutory planning processes, and practical implementation mechanisms, forming the basis for the proposed integrated landscape planning system (

Table 1).

3.5. Text-Mining and Module Construction

The text mining and module development process was conducted to clearly identify the interrelationship and applicability between the landscape planning model and related implementation projects. Text mining can be defined as a process of extracting meaningful or frequently occurring textual information from a body of text data [

6].

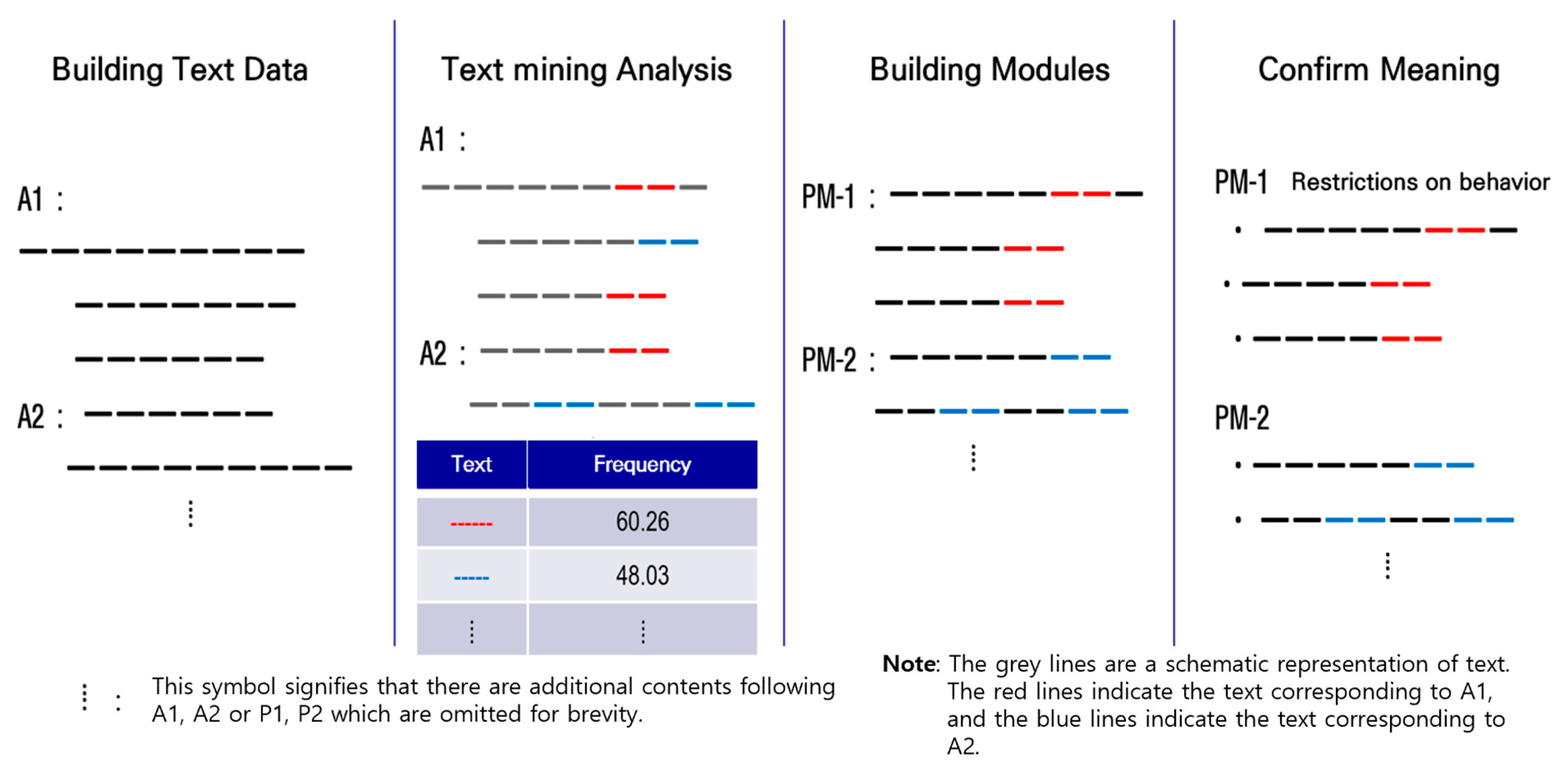

In this study, the improvement measures for detailed planning indicators derived from the reconfigured landscape planning model were first converted into text data. This text data was compiled based on prior studies addressing the indicators of landscape planning models. Through the text-mining process, significant and high-frequency words were identified and extracted. The analysis utilized the Python-based software Orange3 (version 3.35.0), specifically employing its built-in Text Mining Add-on.

For the analysis, a text corpus was constructed by extracting a total of 198 sentences related to improvement measures from prior studies on landscape planning models. To ensure objectivity in the key term selection process, words with a frequency of occurrence of 5 or more were initially extracted.

In the preprocessing stage, tokenization was applied, involving lowercase transformation, accent removal, URL removal, and parsing. In the stop-word removal process, punctuation marks (such ‘as’, ‘,’, ‘.’, ‘/’) and non-substantive words (such as ‘acts’, ‘lots’) were excluded. Subsequently, the improvement measures containing these extracted terms were grouped and organized into unified modules. Each module was assigned a representative term that encapsulates its conceptual meaning, thereby finalizing its definition and scope within the landscape planning framework (

Figure 4).

3.6. Building a Landscape Planning Model Platform

To assess the applicability and activation potential of the landscape planning model, the previously derived results were comprehensively synthesized. For establishing an integrated framework, the landscape planning model was first positioned at the core, followed sequentially by the associated laws, statutory plans, and implementation projects. Subsequently, connections were established between each law and its corresponding statutory plans, allowing the interrelations among legal instruments, plans, and planning indicators to be more clearly understood.

Improvement measures for detailed planning indicators were then visualized in the form of modules, which were linked to relevant implementation projects. This approach enabled the integrated framework to demonstrate both conceptual coherence and practical applicability.

For example, in the case of “installation, management, and planting of roadside trees in rows”, the detailed planning indicators—such as ‘Street tree planting plans’ and ‘Urban greening plans’—were associated with relevant legislation, including the ‘Act on Urban Parks’, ‘Greenbelts’, etc., the ‘Urban and Residential Environment Improvement Act’, and the ‘Act on the Creation and Management of Urban Forests’. Through this process, the model established a clear and functional linkage between planning indicators, legal foundations, and practical implementation mechanisms, thus enhancing the operational feasibility of the landscape planning model within real-world applications.

3.7. Digital Twin Landscape Planning Map Creation

To develop the Digital Twin Landscape Planning Map, it was first necessary to construct a Basic Digital Twin Map, which serves as the foundational layer of the digital twin environment. This basic map represents the primary digital form of the real-world spatial environment.

For this purpose, the software Blender 3D (version 4.0) was employed. Blender 3D was selected due to its high accessibility compared to other similar 3D modeling programs and its excellent compatibility with various applications, which enhances its utility in spatial planning visualization. Furthermore, Blender 3D provides efficient and realistic rendering capabilities, allowing for a simple yet sophisticated representation of real-world environments.

For the creation of the base terrain, data acquired using the ‘OpenStreetMap (OSM)’ Add-on within the program environment were utilized. Using the OSM Add-on, specific target areas were designated based on Google Maps, and their corresponding spatial coordinates were imported into Blender 3D to generate the digital terrain. The target site was selected based on criteria prioritizing areas with diverse landscape elements, where partial urbanization posed a high risk of landscape degradation, and which were situated adjacent to forests, reservoirs, and streams.

The ‘Digital Twin Landscape Planning Map’ was then produced by incorporating planning elements into this foundational map. Unlike conventional replication maps, the planning-oriented digital twin map in this study enables the visualization of dynamic changes within the landscape, rather than merely reproducing existing physical features. To ensure systematic development, the digital twin map was integrated with the previously established ‘Landscape Planning Platform’, and the planning indicators derived from the reconfigured landscape planning model were applied to the 3D representation of the target site.

4. Results

4.1. Reconfiguration of the Landscape Planning Model

The reconfiguration of the landscape planning model was based on a review of prior studies, adapted to reflect the current reality of Korea [

10]. Through a brainstorming process with relevant experts, the planning indicators were modified, and the content was reorganized (

Figure 5,

Table 2).

As a result of redefining the landscape planning model from a conservation-oriented perspective, the model was reorganized into four detailed implementation measures and twenty-eight specific planning indicators. During this process, planning indicators with ambiguous meanings were refined and renamed through a brainstorming process to ensure conceptual clarity. For instance, the indicator previously labeled “restriction on specific forms of land use” was deemed unclear and was revised to “restriction on complete deforestation in forest areas” to provide a more explicit and contextually accurate meaning.

From the nature-experience and recreation-oriented perspective, the model was reconfigured into two detailed implementation measures and thirteen specific planning indicators. In this process, indicators that were difficult to represent spatially or practically were excluded. For example, the indicator “improvement of development direction (development axis) for expansion and linkage measures (A9)” was removed due to the difficulty of expressing it in a spatially measurable manner. Similarly, certain indicators were renamed to better reflect the spatial and cultural realities of South Korea. For instance, “creation of grassland areas for sunbathing and recreation” was reconfigured as “creation of multipurpose lawn plazas (B7)”, reflecting the domestic landscape context and practical planning applicability.

Finally, the two reconfigured models—the conservation-oriented and the nature-experience/recreation-oriented—were integrated into a single, unified landscape planning model. As a result, the final model comprises six detailed implementation measures and forty-one specific planning indicators. A comprehensive comparison between the original and reconfigured planning indicators is presented in the

Appendix A for reference.

4.2. Current Laws, Statutory Plans, and Selection of Implementation Projects Related to Landscape Planning

The analysis of the legal frameworks, statutory plans, and implementation projects related to the establishment of a landscape planning system produced the following results.

First, an examination of the existing laws associated with landscape management revealed that a total of 36 laws are directly or indirectly related to landscape planning. Among these, the “Natural Environment Conservation Act” was identified as a key statute. This law was enacted to protect the natural environment from artificial degradation and to conserve ecosystems and natural landscapes, containing specific provisions related to nature protection and landscape preservation. Additionally, the “Act on Urban Parks, Greenbelts, etc.”, was selected as another major statute, as it regulates the establishment, management, and utilization of urban parks and green spaces—elements that represent crucial components of landscape planning, particularly in relation to urban park development plans.

Second, statutory plans were extracted primarily from those implemented under the selected legal frameworks. To enhance the structural connectivity between statutory plans and landscape planning, overlapping or thematically similar plans were integrated. For instance, the “Comprehensive National Territorial Plan”, “Super-Regional Plan”, and “City/County Comprehensive Plan”, all established under the “Framework Act on the National Territory”, were consolidated under the category of “National Territorial Planning.” Likewise, the “Establishment Policy for Forest Resources” specified in the “Framework Act on Forestry”—which includes reforestation, arboretum creation, and urban forest development reflecting regional characteristics—was incorporated into the broader “Basic Forest Plan”, the higher-level strategic plan. As a result of these integration processes, a total of 75 statutory plans were finally identified as relevant to landscape planning.

Third, through a review of responsible departments within local governments and public agencies, 70 implementation projects were extracted. For example, the “Ecosystem Services Payment Program”, administered by the Ministry of Environment, was included as a relevant project. This program establishes contracts with local residents to promote ecosystem service conservation activities—such as maintaining rice straw for wildlife feeding and habitat creation, or developing scenic forest landscapes—which contribute to the formation of aesthetically valuable landscapes. Some project categories were further consolidated; for instance, the “Cultural and Educational Street Development Project” and the “Design Street Improvement Project” were merged into the unified category of “Streetscape Improvement Projects”, encompassing all landscape projects focused on the aesthetic and functional enhancement of urban streets.

The interrelationships among the identified laws, statutory plans, and implementation projects related to landscape planning are summarized and illustrated in

Figure 6, which presents the comprehensive structural linkage established through this analysis.

4.3. Text-Mining and Module Construction

The text-mining results revealed that words such as “restriction,” “creation,” and “edge” frequently appeared across the dataset. To refine these results, a filtering process was performed to isolate words with meaningful or actionable implications for improvement measures. Common or functionally insignificant words such as “is” and “and” were excluded (

Figure 7).

Through a subsequent brainstorming process, words with similar or overlapping meanings—such as “restriction of activity” and “restriction of destructive activity”—were unified under a single representative term, “restriction of destructive activity.” This iterative refinement process resulted in the identification of nineteen representative terms including “restriction of destructive activity,” “restriction of logging,” “maintenance of soil,” “afforestation activities,” “cultivation of landscape crops,” and “creation of walking trails.”

Among these, eleven terms with ecological and preservation-oriented implications—such as “restriction of destructive activity” and “afforestation activities”—were classified as the Preservation Module (PM). The remaining eight terms, which emphasize nature-experience and recreational aspects—such as “cultivation of landscape crops” and “creation of walking trails”—were categorized as the Recreation Module (RM). And the improvement measures for generally accepted standards, areas, etc., were classified as module X.

A closer examination of the Preservation Modules (PMs) revealed that PM-1 was derived from the repeated appearance of improvement measures related to the restriction of landscape and habitat destruction activities. These items were integrated into a single module encompassing restrictions on actions that damage valuable residual landscape elements or alter the appearance of natural monuments. Accordingly, the module was named “Restriction of Destructive Activities.”

Similarly, PM-4 was established to address recurring content related to the protection and maintenance of water spaces. This module includes m easures that restrict pollution and land reclamation activities capable of altering water resources within the study area, as well as the protection and management of small-scale water bodies, surface water, and groundwater. As these measures focus on the protection and prevention of deterioration of aquatic environments, the module was named “Restriction on Alteration and Degradation of Water Spaces.”

From the Recreation Modules (RMs) perspective,

RM-1 contains measures concerning “ecological carrying capacity”, proposing guidelines such as estimating the number of visitors and determining the appropriate scale of parking facilities to minimize ecological impact. RM-2 focuses on the creation of walking trails, with improvement measures including “linkage with parking areas”, “connection to viewing spaces”, and “maximum width of 2m”. RM-3 centers on the concept of nature connectivity, which appeared repeatedly throughout the data; this module was therefore titled “Nature-Friendly Development.” A description of the entire module for conservation aspects (PM) and the module for recreation aspects (RM) are presented in

Appendix A and

Appendix B, respectively.

However, the text data used for text mining and the resulting modules were primarily limited to conservation and nature-experience/recreation aspects. To enhance the extensibility of the model in future research, it is necessary to incorporate a broader range of factors, including aesthetic/visual elements and user convenience amenities.

4.4. Building a Landscape Planning Model Platform

To establish the landscape planning platform, the legal frameworks, statutory plans, and implementation projects were systematically organized in sequential order, centered around the reconfigured landscape planning model. This hierarchical structuring process aimed to clarify the interconnections among the core planning elements (

Figure 8).

For example, in the case of “installation, management, and planting of roadside trees,” the detailed planning indicators related to roadside tree planting and management are directly linked to the “Street Tree Establishment Plan” and the “Urban Greening Plan”. The relevant legal frameworks include the “Act on Urban Parks, Greenbelts, etc.”, the “Urban and Residential Environment Improvement Act”, and the “Act on the Creation and Management of Urban Forests”. Additionally, the associated module—PM-X—addresses elements such as planting spacing and tree specifications, while the relevant implementation projects include “Street Tree Development Projects” and “Urban Landscape Improvement Projects”.

Another example is “maintenance and improvement of deteriorated buildings.” This element connects to statutory plans such as the “Basic Plan for Urban Residential Environment Improvement”, the “Comprehensive Plan for Rural Village Revitalization”, and the “Living Environment Improvement Plan”. The corresponding legal frameworks include the “Rural Development Act”, the “Urban and Residential Environment Improvement Act”, and the “Special Act on the Promotion of Quality of Life for Farmers and Fishers” and “the Development of Rural Areas”. The associated module—RM-8—addresses improvement and maintenance measures for built environments, and its related implementation projects include the “New Village Development Project”, the “Urban Landscape Project”, and the “Rural Spatial Improvement Project”.

4.5. Digital Twin Landscape Planning Map Creation

The primary objective of this study is to identify indicators, laws, plans, and projects applicable to the target site using the reconfigured landscape planning model and to propose a methodology for implementing them within a digital twin environment. The landscape planning platform, utilizing this reconfigured model, enables the selection of applicable indicators and the visualization of associated legal and planning elements. Furthermore, by projecting this visualized information onto the digital twin, the resulting physical and environmental transformations can be intuitively observed.

To construct the digital terrain for the digital twin environment, the process was initiated by selecting the target area using OpenStreetMap (OSM). A rectangular boundary was defined within the OSM interface to establish the specific spatial extent. Subsequently, the selected spatial range was imported into Blender 3D program(version 4.5,

https://www.blender.org/) to generate a single terrain layer. In the final stage, aerial imagery corresponding to the area was overlaid onto this terrain layer to complete the base terrain of the study site (

Figure 9).

However, it was confirmed that while OSM offers high-level detail for major global cities such as New York and London, it presents relative limitations when applied to the domestic context of Korea. Despite these constraints, OSM was utilized in this study as it provides accessibility to spatial information that is often difficult to obtain or share due to local data security regulations.

Nonetheless, as OSM relies on global mapping system standards, it demonstrated certain deficiencies in accurately depicting specific spatial elements—such as street trees, buildings, roads, and water bodies—within Korea. These fundamental data issues inevitably lead to uncertainty in spatial analysis and data disparity between regions. Therefore, to overcome these limitations, future research must consider supplementing OSM with national geospatial data or alternative mapping technologies to enhance the precision and applicability of the digital twin landscape modeling process.

The results of applying the conservation-oriented landscape planning model to the ‘Digital Twin Landscape Planning Map’ are as follows (

Figure 10). As a representative example, the afforestation indicator was analyzed. According to Kim [

5], afforestation is implemented when establishing new forest stands or expanding existing ones.

In this study, the afforestation indicator was prioritized for areas with existing forest patches within the target site (

Figure 5). It was also applied to locations requiring enhanced landscape diversity or changes in the land-use mosaic to improve ecological connectivity. Furthermore, afforestation planning was established along major roads where visual screening, noise reduction, and air quality improvement were necessary. Suitable sites included abandoned lands and fallow fields that aligned with the ecological and visual objectives of afforestation.

Each afforestation zone was designed with a minimum area of 0.5 hectares to ensure landscape continuity and ecological efficiency. Deciduous broad-leaved tree species suitable for local environmental conditions were selected to enhance noise absorption and air purification functions. Additionally, the results of applying various landscape planning modules are presented in

Figure 11.

Simulation results using Blender 3D indicated that the application of these planning indicators is projected to result in an approximate 10–15% increase in woodland area compared to the existing forest cover. However, for more precise quantitative comparisons, further research is deemed necessary to enhance map resolution and digital twin construction through data exchange with the National Spatial Information Open Platform (V-World). Furthermore, future studies should also address the development of an automated framework for the application of planning indicators.

In applying the recreation-oriented landscape planning model to the Digital Twin Landscape Planning Map, several key spatial indicators were implemented to visualize areas designed for nature-based recreational activities.

First, the indicator “multipurpose lawn plaza” represents a fundamental setting for outdoor recreation, accommodating activities such as sunbathing, picnicking, and light exercise. In this study, the multipurpose lawn plaza was designed in connection with a small-scale ecological park previously developed in the model, forming an enclosed space surrounded by forested areas. This spatial configuration enhances user comfort and provides a natural sense of immersion within the landscape.

Second, the indicator “small-scale waterside recreation area” utilizes flowing water systems such as rivers and streams to create spaces that promote nature experience and leisure. According to Cho [

10], these areas hold significant value for integrating ecological and recreational functions within the landscape. In the study site, small-scale waterside recreation areas were developed to supplement the existing small streams with high ecological value. Like the multipurpose lawn plaza, they were connected to the internal stream system of the ecological park and designed within the limits of the site’s ecological carrying capacity.

For the spatial composition, shallow water zones were created to encourage interactive nature experiences, such as stepping-stone crossings and wading areas, while rest facilities such as pavilions and benches were strategically placed around the site to provide comfort and enhance usability.

The results of applying various recreation models to the target site are presented in

Figure 12.

5. Discussion

The integration of landscape planning with digital twin technology presents a paradigm shift from static documentation to dynamic, data-driven spatial management. Traditional landscape plans were limited in their ability to communicate spatial vision, as they relied heavily on two-dimensional mapping and descriptive narratives. The incorporation of digital twin platforms allows for interactive visualization, temporal simulation, and participatory feedback, providing a multidimensional planning tool.

This integration facilitates the following benefits. Multi-layered 3D models improve comprehension of spatial relationships among ecological, infrastructural, and cultural components. Simulation of environmental changes under various scenarios enables more objective and adaptive policy-making. Virtual representations increase accessibility for residents, allowing participatory decision-making. Real-time visualization of departmental responsibilities improves inter-agency communication and policy coherence. Hence, the digital twin system bridges the gap between conceptual planning and implementation by transforming abstract models into tangible, experiential environments.

From an administrative perspective, this study suggests that the integration model could serve as a decision-support framework linking policy formulation, implementation, and evaluation. By visualizing interconnections among laws, plans, and projects, the system clarifies administrative responsibilities and reduces redundancy. Moreover, the model contributes to multi-level governance by providing a common platform where national, regional, and local stakeholders can interact. The digital twin can also be used for real-time landscape monitoring, assisting in the continuous assessment of ecological degradation or visual clutter. It establishes an institutional foundation for adaptive management, where planning outputs are regularly updated according to changing environmental data.

Despite its strengths, several limitations remain with regard to implementing the proposed model.

Integration between public GIS databases and digital twin platforms is constrained due to differing data formats and security policies. There is a lack of unified manuals and legal guidelines for linking planning procedures to digital twin frameworks. High computational demands and software complexity limit adoption by local governments and small municipalities. While visualization tools enhance understanding, actual participation still requires effective facilitation and governance design. To overcome these challenges, collaborative frameworks between academic institutions, government agencies, and private developers should be established to promote open-source data sharing and interoperability standards.

6. Conclusions

The comprehensive framework proposed in this study can be applied to future landscape planning procedures, providing a more systematic and procedural approach to planning and implementing projects for landscape conservation, nature experience, and recreation. In particular, the integrated system established in this study offers a foundation for enhancing the intuitiveness, accessibility, and applicability of landscape planning if further developed into a programmable platform. Such digital integration is expected to overcome the existing limitations associated with manual interpretation and fragmented planning processes.

The ‘Digital Twin 3D Landscape Planning Map’ developed in this study also presents notable advantages. By enabling the visualization of landscape changes prior to construction or project implementation, it can reduce potential economic and human resource losses caused by subjective misjudgments in conventional planning. When construction projects are executed based on 3D planning models, the realism and applicability of the outcomes are significantly improved. Moreover, through continuous data accumulation and simulation, these models enable the prevention of accidents and the forecasting of landscape transformations. Even after project completion, they facilitate the rapid identification of defects or discrepancies, thereby minimizing budgetary waste and serving as an essential tool for sustainable landscape management.

However, several challenges remain for future research. To enhance the applicability of the proposed platform, it is necessary to expand and refine the legal, planning, and project databases related to landscape management. Additionally, while the current planning model provides a generalized framework, further studies should focus on developing region-specific landscape planning models that reflect the unique spatial and ecological characteristics of each area.

Furthermore, to improve the precision of 3D maps, it is deemed necessary to secure detailed spatial and 3D data through agreements and collaboration with ‘V-World’, the National Spatial Information Platform. Finally, more detailed research is required on the methodology for generating 3D planning maps using the landscape planning platform, in order to establish a standardized and scalable approach for practical implementation.