Life Cycle Environmental Impact Assessment of Gold Production in an Artisanal Small-Scale Mine in Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

Novel Contributions of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Brief Social and Environmental Overview of Mina Nueva Mine

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

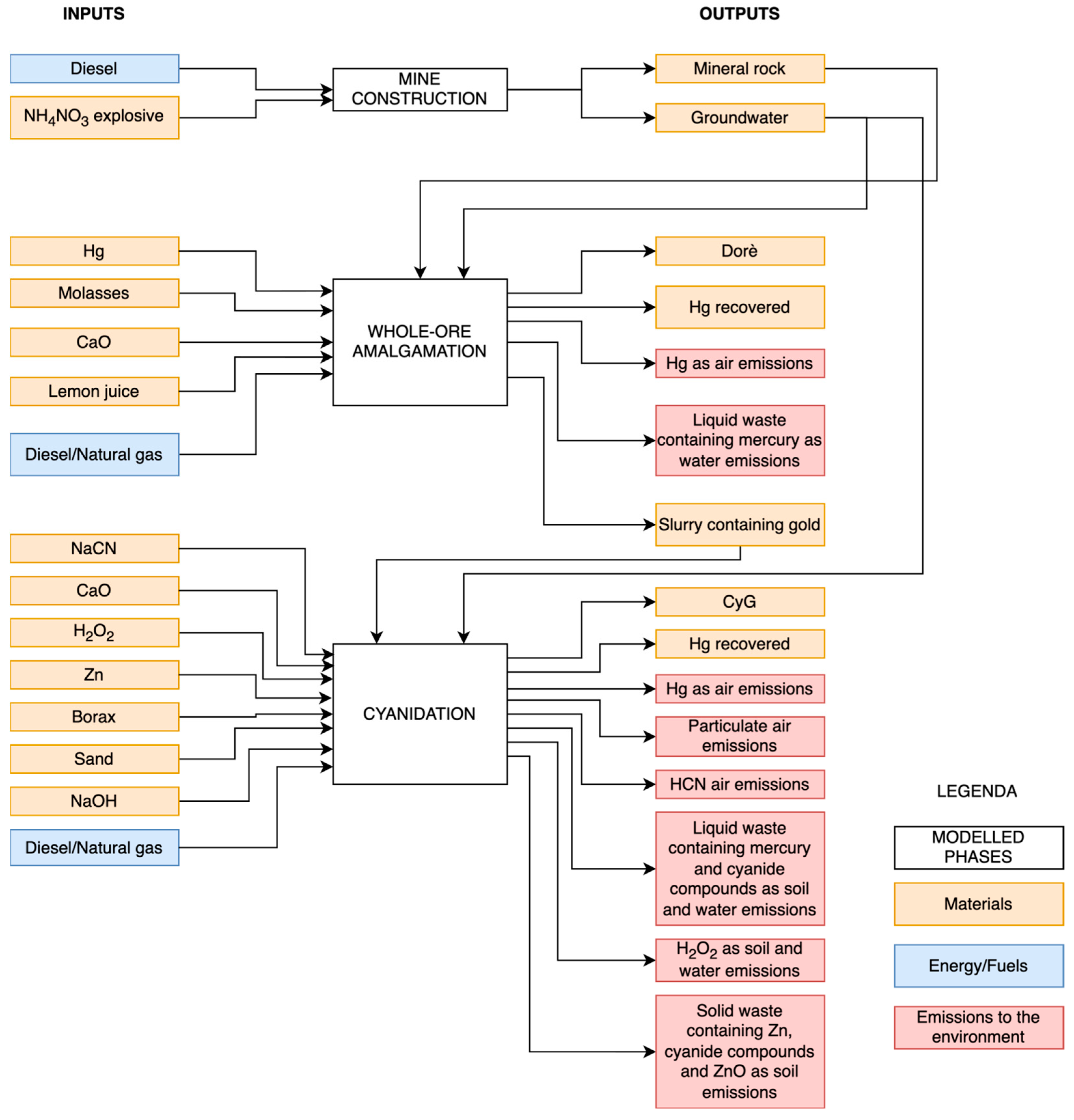

2.2.1. Goal and Scope Definition

2.2.2. The Function of the System, the System Studied, and Its Functional Unit

2.2.3. System Boundaries

2.2.4. Data Quality, Life Cycle Inventory, and Life Cycle Impact Assessment

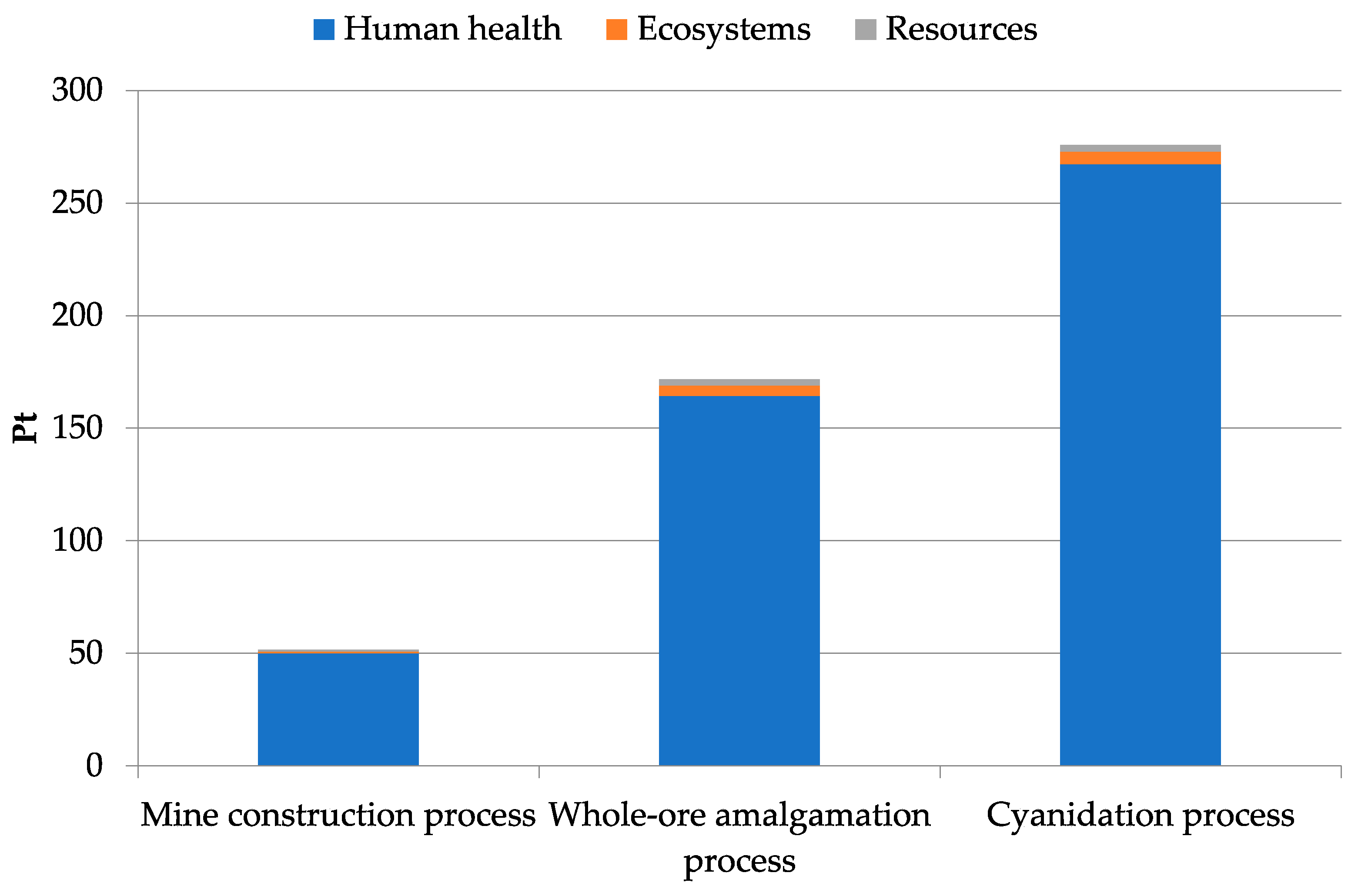

3. Results and Discussion

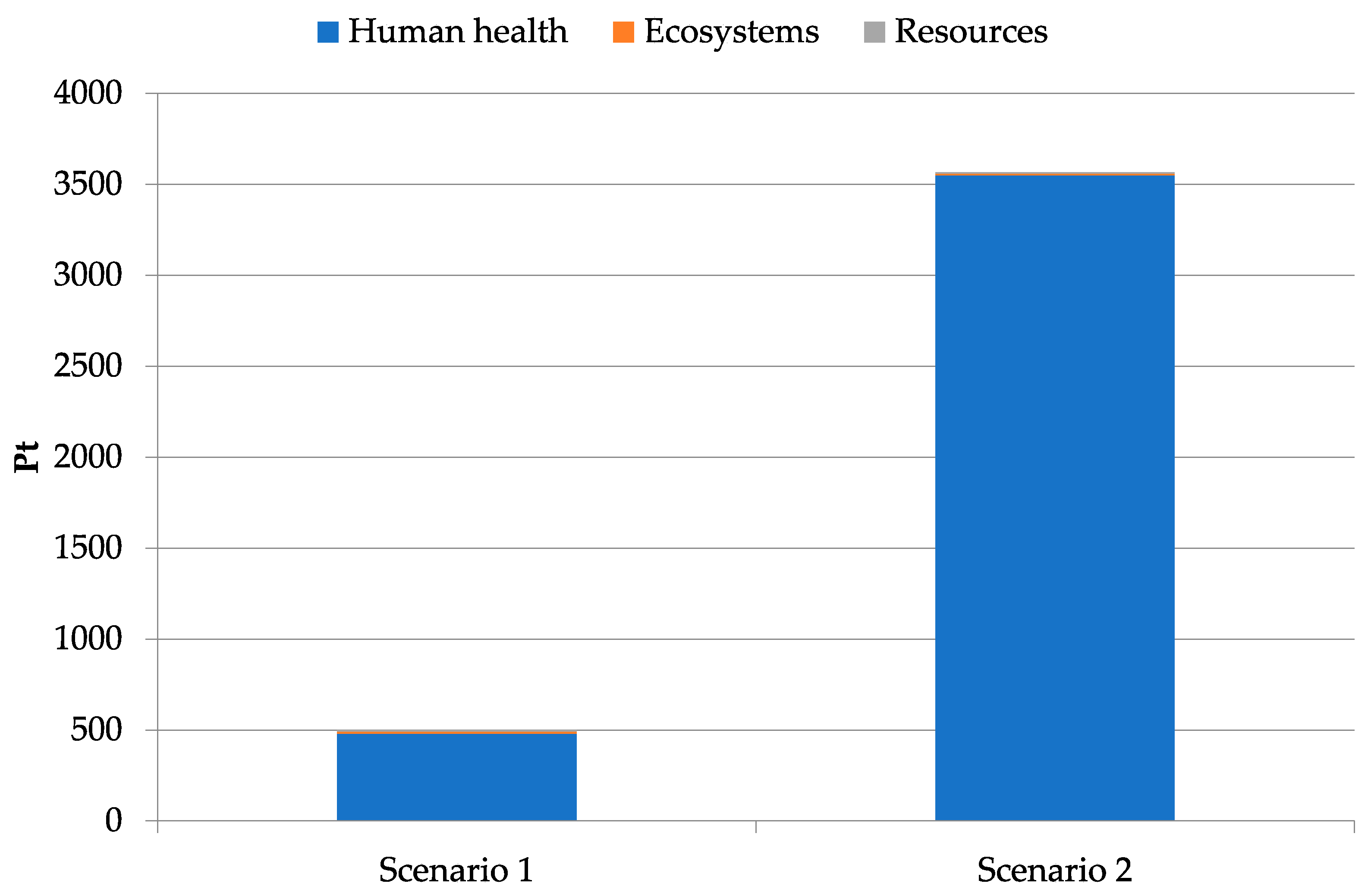

Sensitivity Analysis

4. Limitations and Potential Improvements of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Gold Council. Gold Demand Trends Full Year 2023. Supply. Available online: https://www.gold.org/goldhub/research/gold-demand-trends/gold-demand-trends-full-year-2023/supply#:~:text=Total%20gold%20supply%20in%202023,and%20recycling%20both%20posted%20growth.&text=Full%2Dyear%20recycled%20gold%20supply,record%20annual%20average%20gold%20price (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Barume, B.; Naeher, U.; Ruppen, D.; Schütte, P. Conflict minerals (3TG): Mining production, applications and recycling. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2016, 1, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerwein, T. Gold mining and development in Côte d’Ivoire: Trajectories, opportunities and oversights. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G.; Maconachie, R. Artisanal and small-scale mining and the Sustainable Development Goals: Opportunities and new directions for sub-Saharan Africa. Geoforum 2020, 111, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamundala, G. Formalization of artisanal and small-scale mining in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo: An opportunity for women in the new tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold (3TG) supply chain? Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Gold Council. Lessons Learned on Managing the Interface Between Large-Scale and Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining. Available online: https://www.swissbettergoldassociation.ch/sites/default/files/2022-04/ASGM-Report-2022-English.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- UNODC, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Methodological Proposal for the Estimation of Illicit Financial Flows Associated with Illicit Cocaine Markets and Illicit Gold Mining in Colombia. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/IFF/5_Colombia_-_IFFs_from_Cocaine_Trafficking_and_Illegal_Gold_Mining.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Seccatore, J.; Veiga, M.; Origliasso, C.; Marin, T.; De Tomi, G. An estimation of the artisanal small-scale production of gold in the world. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 496, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Watari, T.; Seccatore, J.; Nakajima, K.; Nansai, K.; Takaoka, M. A review of gold production, mercur consumption, and emission in artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM). Resour. Policy 2023, 81, 10337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Gold Council, Press Release. ASGM Report 2022 Press Release. Available online: https://www.gold.org/news-and-events/press-releases/asgm-report-2022-press-release (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- IISD. Global Trends in Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM): A Review of Key Numbers and Issues International Institute for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.iisd.org/publications/global-trends-artisanal-and-small-scale-mining-asm-review-key-numbers-and-issues (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- UNEP United Nations Environment Programme. Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining. Global Mercury Partnership. Global Mercury Partnership. Available online: https://www.unep.org/globalmercurypartnership/what-we-do/artisanal-and-small-scale-gold-mining-asgm (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- ASM Inventory. World Maps of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining. The Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining Knowledge Sharing Archive. Available online: https://artisanalmining.org/Inventory/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- World Gold Council. Gold Demand Trends Full Year 2023. Available online: https://www.gold.org/goldhub/research/gold-demand-trends/gold-demand-trends-full-year-2023 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Mason, R.; Pirrone, N. Mercury Fate and Transport in the Global Atmosphere. In Emissions, Measurements and Models, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzantini, U. L’inferno al Mercurio Delle Miniere D’oro in Indonesia: Avvelenati Terra, Acqua, e Uomini. Green Report. Available online: https://www.greenreport.it/news/green-economy/5637-linferno-al-mercurio-delle-miniere-doro-in-indonesia-avvelenati-terra-acqua-e-uomini (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Palacios, Y.; Rosa, J.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Trace elements in sediments and fish from Atrato River: An ecosystem with legal rights impacted by gold mining at the Colombian Pacific. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme. Reducing Mercury Use in Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining. A Practical Guide. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/reducing-mercury-use-artisanal-and-small-scale-gold-mining-practical-guide (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Palacios-Torres, Y.; Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Mercury pollution by gold mining in a global biodiversity hotspot, the Choco biogeographic region, Colombia. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordy, P.; Veiga, M.M.; Salih, I.; Al-Saadi, S.; Console, S.; Garcia, O.; Mesa, L.A.; Velásquez-López, P.C.; Roeser, M. Mercury contamination from artisanal gold mining in Antioquia, Colombia: The world’s highest per capita mercury pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 410–411, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, E.A.; Diaz, R.; Bogale Tadesse, B.; Browner, R. A review on current practices and emerging technologies for sustainable management, sequestration and stabilization of mercury from gold processing streams. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 249, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.M.; Angeloci-Santos, G.; Meech, J.A. Review of barriers to reduce mercury use in artisanal gold mining. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2014, 1, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordy, P.; Veiga, M.; Crawford, B.; Garcia, O.; Gonzalez, V.; Moraga, D.; Roeser, M.; Wip, D. Characterization, mapping, and mitigation of mercury vapour emissions from artisanal mining gold shops. Environ. Res. 2013, 125, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimoloye, I.; Ololade, O. Potential implications of gold-mining activities on some environmental components: A global assessment (1990 to 2018). J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 2432–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telmer, K.H.; Veiga, M.M. World emissions of mercury from artisanal and small scale gold mining. In Mercury Fate and Transport in the Global Atmosphere; Mason, R., Pirrone, N., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 131–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mantey, J.; Nyarko, K.B.; Owusu-Nimo, F.; Awua, K.A.; Bempah, C.K.; Amankwah, R.K.; Akatu, W.E.; Appiah-Effah, E. Mercury contamination of soil and water media from different illegal artisanal small-scale gold mining operations (galamsey). Heliyon 2020, 6, e04312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, M.J. Assessing releases of mercury from small-scale gold mining sites in Ghana. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2017, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.M.; Baker, R.F. Protocols for Environmental and Health Assessment of Mercury Released by Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Miners; Produced for the Global Mercury Project; GEF/UNDP/UNIDO: Vienna, Austria, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Taux, K.; Kraus, T.; Kaifie, A. Mercury exposure and its health effects in workers in the artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) Sector-A systematic review. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esdaile, L.J.; Chalker, J.M. The Mercury Problem in Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining. Chem. A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6905–6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drace, K.; Kiefer, A.M.; Veiga, M.M. Cyanidation of Mercury-Contaminated Tailings: Potential Health Effects and Environmental Justice. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2016, 3, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S.; Agrawal, S.; Mikha, D.; Vitamerry, K.; Le Billon, P.; Veiga, M.; Konolius, K.; Paul, B. Phasing Out Mercury? Ecological Economics and Indonesia’s Small-Scale Gold Mining Sector. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M. Antioquia, Colombia: The World’s Most Polluted Place by Mercury: Impressions from Two Field Trips. United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Available online: https://redjusticiaambientalcolombia.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/final_revised_feb_2010_veiga_antioquia_field_trip_report.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Kosai, S.; Nakajima, K.; Yamasue, E. Mercury mitigation and unintended consequences in artisanal and small-scale gold mining. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, M.M.; Angeloci, G.; Hitch, M.; Velasquez-Lopez, P.C. Processing centres in artisanal gold mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlin, J. Informal gold miners, security and development in Colombia: Charting the way forward. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2018, 5, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defensoría Delegada para los Derechos Colectivos y del Ambiente; Defensoría del Pueblo, Colombia. MINERÍA DE HECHO EN COLOMBIA. Available online: https://www2.congreso.gob.pe/sicr/cendocbib/con4_uibd.nsf/F11B784C597AC0F005257A310058CA31/$FILE/La-miner%C3%ADa-de-hecho-en-Colombia.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Congreso de Colombia. LEY 1658 DE 2013. Por Medio de la Cual se Establecen Disposiciones Para la Comercialización y el Uso de Mercurio en las Diferentes Actividades Industriales del país, se Fijan Requisitos e Incentivos Para su Reducción y Eliminación y se Dictan Otras Disposiciones. Available online: http://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?ruta=Leyes/1685943 (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- MADS, Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible de Colombia. RESOLUCIÓN 631 DE 2015 Diario Oficial No. 49.486 de 18 de Abril de 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.minambiente.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/resolucion-631-de-2015.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Valdivia, S.M.; Ugaya, C.M.L. Life Cycle Inventories of Gold Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining Activities in Peru. J. Ind. Ecol. 2011, 15, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbeláez, E.; Villamizar, D.; Trujillo, N. New voucher specimens and tissue samples from an avifaunal survey of the Middle Magdalena Valley of Bolívar, Colombia, bridge geographical and temporal gaps. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2021, 132, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Reyes, M. In Search of Ordenamiento Ambiental Territorial in the Peasant Reserve Zones of Colombia. Master’s Thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://surface.syr.edu/etd/292 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Betancur, M.S. MINERÍA DEL ORO, TERRITORIO Y CONFLICTO EN COLOMBIA. Retos y Recomendaciones Para la Protección de los Derechos Humanos y del Medio Ambiente. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, Oficina Bogotá—Colombia. Available online: https://co.boell.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/20190612_Mineri%CC%81a%20del%20oro%2C%20territorio%20y%20conflicto%20en%20colombia%20para%20web.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Portuguez, A.L.M. The Cimitarra River Valley Rural Reserve Zone: An Unfinished Exercise in Citizen Participation and Collective Management of Territory. Cuad. Geogr. Rev. Colomb. Geogr. 2011, 20, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- ACVC, UNDP and Soluterra. Technical Report: Estudio Participativo de Tenencia de la Tierra y el Territorio, Usos y Conflictos en la Zona de Reserva Campesina del Valle del río Cimitarra—Cartografía. 2014. Available online: https://reservacampesinariocimitarra.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Informe-final-PNUD-ACVC-20072014-4_compressed.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Vargas, P.; Sonia, C. Peasant reserve zones as a frame for the guarantee of collective rights of peasant collectivities in Colombia: The case of Cimitarra River Valley. Global Campus Europe—EMA. European Master’s Degree in Human Roghts and Democratisation. Master’s Thesis, University of Deusto, Bilbao, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, S.J. Labour challenges and mercury management at gold mills in Zimbabwe: Examining production processes and proposals for change. Nat. Resour. Forum 2009, 33, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACVC, INCODER, PDPMM. Plan de Desarrollo Sostenible de la Zona de Reserva Campesina del Valle del río Cimitarra ZRC—Asociación Campesina del Valle del río Cimitarra. 2012. Available online: https://reservacampesinariocimitarra.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/PLAN-DE-DESARROLLO-ZRC-VALLE-RIO-CIMITARRA-2_compressed.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- ISO 14040:2021; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. UNI EN ISO: Milan, Italy, 2021.

- ISO 14044:2021; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. UNI EN ISO: Milan, Italy, 2021.

- Veiga, M.M.; Maxson, P.A.; Hylander, L.D. Origin and consumption of mercury in small-scale gold mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkaman, P.; Veiga, M.M. Comparing cyanidation with amalgamation of a Colombian artisanal gold mining sample: Suggestion of a simplified zinc precipitation process. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 13, 101208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, O.J.R.; Mendoza, L.E.M. Sustainability of the artisanal and small-scale gold mining in northeast Antioquia-Colombia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecoinvent Center, Ecoinvent Database Version 3.10. Life Cycle Inventories. Available online: http://www.ecoinvent.ch (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Pré Sustainability SimaPro. Available online: https://www.pre-sustainability.com/simapro (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Wernet, G.; Bauer, C.; Steubing, B.; Reinhard, J.; Moreno-Ruiz, E.; Weidema, B. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): Overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, A.M. Significance of decision-making for LCA methodology. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2010, 20, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILCD Handbook, General Guide for Life Cycle Assessment—Detailed Guidance. Available online: https://eplca.jrc.ec.europa.eu/uploads/ILCD-Handbook-General-guide-for-LCA-DETAILED-GUIDANCE-12March2010-ISBN-fin-v1.0-EN.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.; Zijp, M.; Hollander, A.; Van Zelm, R. ReCiPe2016: A harmonized life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bare, J.C. Tool for the Reduction and Assessment of Chemical and Other Environmental Impacts (TRACI), Software Name and Version Number: TRACI Version 2.1, User’s Manual; US EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, R.K.; Bachmann, T.M.; Gold, L.S.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Jolliet, O.; Juraske, R.; Koehler, A.; Larsen, H.F.; MacLeod, M.; Margni, M.; et al. USEtox—The UNEP-SETAC toxicity model: Recommended characterisation factors for human toxicity and freshwater ecotoxicity in life cycle impact assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2008, 13, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieda, B. Application of stochastic approach based on Monte Carlo (MC) simulation for life cycle inventory (LCI) to the steel process chain: Case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 481, 49–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuda, H.; Shihang, L.; Hao, J.; Xu, Z. Study on the effect of multi-stage filtration strategy on the wet filtration dust collector performance. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. AP-42, Compilation of Air Pollutant Emission Factors, Volume I: Stationary Point and Area Sources, Appendix B.2: Generalized Particle Size Distributions, Category 3: Mechanically Generated/Aggregated, Unprocessed Ores. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-11/documents/appb-2.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ciroth, A.; Muller, S.; Weidema, B.; Lesage, P. Empirically based uncertainty factors for the pedigree matrix in Ecoinvent. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Impact Category | Unit | Total | Mine Construction Process | Whole-Ore Amalgamation Process | Cyanidation Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global warming | kg CO2 eq | 4.66 × 1003 | 1.14 × 1003 | 1.44 × 1003 | 2.08 × 1003 |

| Stratospheric ozone depletion | kg CFC11 eq | 3.56 × 10−03 | 1.10 × 10−03 | 1.06 × 10−03 | 1.40 × 10−03 |

| Ionizing radiation | kBq Co-60 eq | 6.01 × 1001 | 8.03 × 1000 | 1.80 × 1001 | 3.41 × 1001 |

| Ozone formation, Human health | kg NOx eq | 2.91 × 1001 | 1.21 × 1001 | 7.64 × 1000 | 9.40 × 1000 |

| Fine particulate matter formation | kg PM2.5 eq | 8.66 × 1000 | 3.22 × 1000 | 2.21 × 1000 | 3.23 × 1000 |

| Ozone formation, Terrestrial ecosystems | kg NOx eq | 3.00 × 1001 | 1.23 × 1001 | 7.92 × 1000 | 9.76 × 1000 |

| Terrestrial acidification | kg SO2 eq | 1.83 × 1001 | 7.06 × 1000 | 4.75 × 1000 | 6.49 × 1000 |

| Freshwater eutrophication | kg P eq | 7.37 × 10−01 | 8.18 × 10−02 | 2.33 × 10−01 | 4.23 × 10−01 |

| Marine eutrophication | kg N eq | 4.60 × 10−01 | 1.36 × 10−02 | 1.76 × 10−01 | 2.71 × 10−01 |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 1.46 × 1006 | 1.08 × 1004 | 7.66 × 1005 | 6.87 × 1005 |

| Freshwater ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 1.80 × 1003 | 1.97 × 1001 | 4.44 × 1001 | 1.73 × 1003 |

| Marine ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 7.85 × 1002 | 3.68 × 1001 | 1.95 × 1002 | 5.53 × 1002 |

| Human carcinogenic toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 2.00 × 1003 | 3.16 × 1002 | 4.85 × 1002 | 1.20 × 1003 |

| Human non-carcinogenic toxicity | kg 1,4-DCB | 5.95 × 1004 | 3.24 × 1002 | 2.40 × 1004 | 3.52 × 1004 |

| Land use | m2a crop eq | 8.26 × 1002 | 4.26 × 1002 | 1.67 × 1002 | 2.34 × 1002 |

| Mineral resource scarcity | kg Cu eq | 1.66 × 1003 | 2.67 × 1000 | 9.36 × 1002 | 7.23 × 1002 |

| Fossil resource scarcity | kg oil eq | 1.29 × 1003 | 3.16 × 1002 | 4.01 × 1002 | 5.70 × 1002 |

| Water consumption | m3 | −3.39 × 1002 | −5.48 × 1002 | 8.72 × 1001 | 1.22 × 1002 |

| Damage Category | Unit | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human health | Pt | 4.82 × 1002 | 3.55 × 1003 |

| Ecosystem | Pt | 1.09 × 1001 | 1.09 × 1001 |

| Resources | Pt | 6.44 × 1000 | 6.44 × 1000 |

| Impact Category | Unit | Mean | Median | SD | CV % | 2.5% | 97.5% | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine particulate matter formation | kg PM2.5 eq | 3.00 × 1002 | 2.72 × 1002 | 1.24 × 1002 | 4.15 × 1001 | 1.40 × 1002 | 6.39 × 1002 | 3.93 × 1000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ruffini, V.; Neri, P.; Gomez, F.H.; Rosa, R.; Mortalò, C.; Vaccari, M.; Ferrari, A.M. Life Cycle Environmental Impact Assessment of Gold Production in an Artisanal Small-Scale Mine in Colombia. Sustainability 2026, 18, 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020770

Ruffini V, Neri P, Gomez FH, Rosa R, Mortalò C, Vaccari M, Ferrari AM. Life Cycle Environmental Impact Assessment of Gold Production in an Artisanal Small-Scale Mine in Colombia. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020770

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuffini, Vanessa, Paolo Neri, Franco Hernan Gomez, Roberto Rosa, Cecilia Mortalò, Mentore Vaccari, and Anna Maria Ferrari. 2026. "Life Cycle Environmental Impact Assessment of Gold Production in an Artisanal Small-Scale Mine in Colombia" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020770

APA StyleRuffini, V., Neri, P., Gomez, F. H., Rosa, R., Mortalò, C., Vaccari, M., & Ferrari, A. M. (2026). Life Cycle Environmental Impact Assessment of Gold Production in an Artisanal Small-Scale Mine in Colombia. Sustainability, 18(2), 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020770