Streetscapes and Street Livability: Advancing Sustainable and Human-Centered Urban Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1 (Comprehension): How do essential streetscape components contribute to street livability?

- RQ2 (Conceptual-Analytical): what synergies integrate advanced and innovative practices into streetscapes to enhance street livability?

- RQ3 (Intervention): Did the recent attempts and implementations show success, and how?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

- Core Concepts: derived from RQ1, focusing on conceptual foundations, utilizing search strings: (“Street livability” OR “urban livability”) AND (“human-centered design” OR “sustainable urban development”) AND “walkability”

- Streetscape Components: addressing the identified research gap related to microscale streetscapes, utilizing search string: “Street vegetation” OR “street furniture” OR “street lighting” AND (“design” OR “performance” OR “microclimate”)

- Intersections/Recurrent Themes/Innovative Practices: generated through consistent synthesis and snowballing techniques during the review process, utilizing search strings: “Smart Street” OR “biomimicry” OR “renewable energy” AND (“urban design” OR “Superblock”)

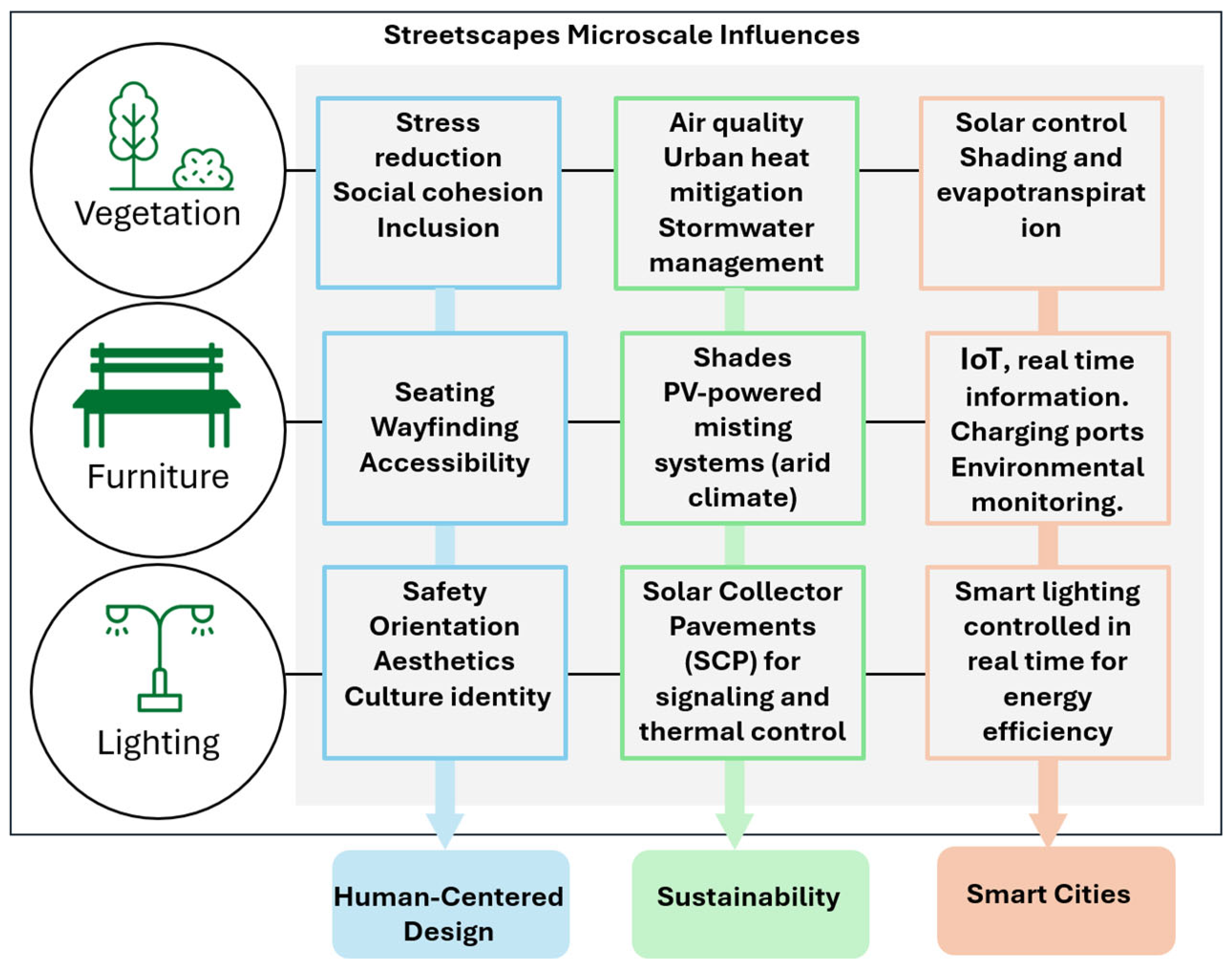

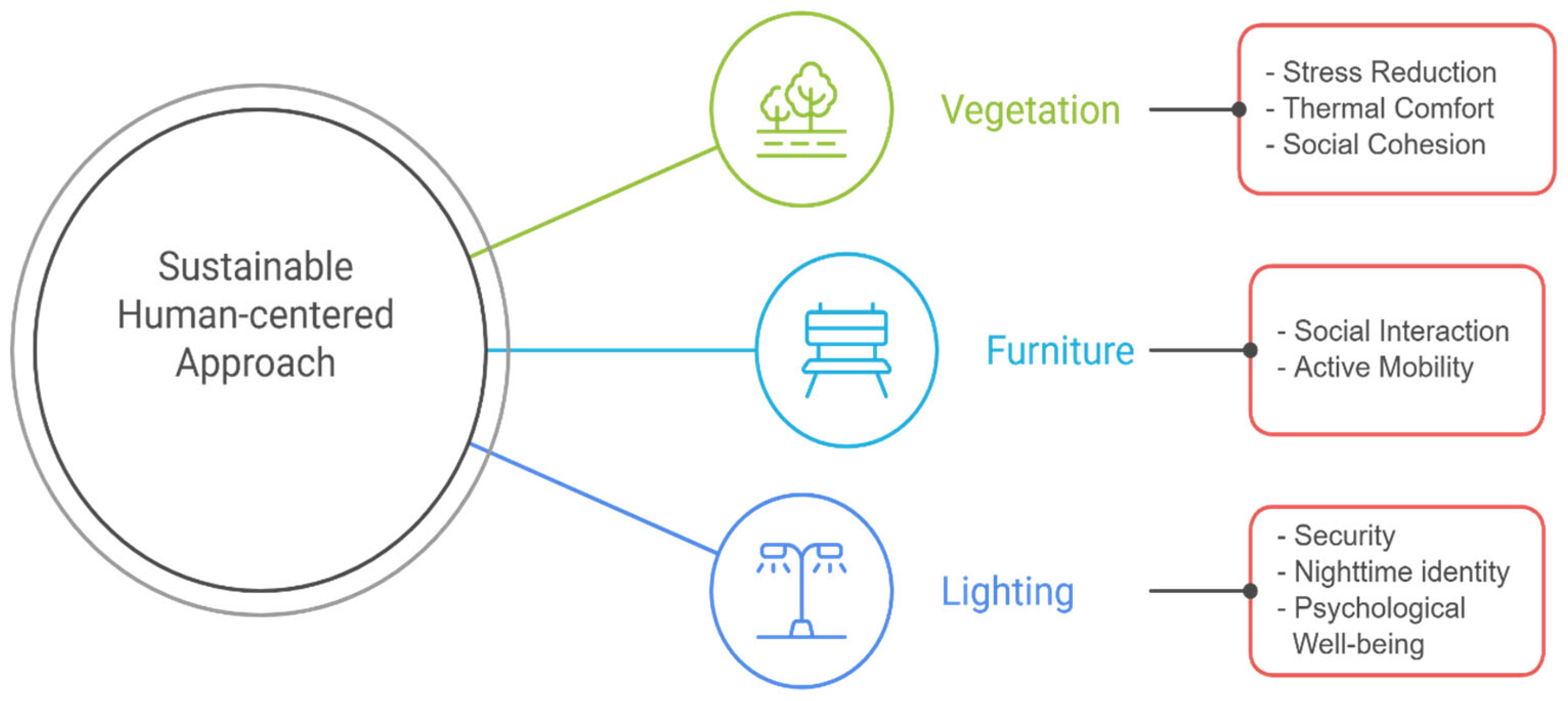

2.2. Conceptual Model

3. Literature Review

3.1. Street Livability

3.2. Streetscapes

3.3. Vegetation

3.4. Furniture

3.5. Lighting

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Istrate, A.-L.; Chen, F. Liveable streets in Shanghai: Definition, characteristics and design. Prog. Plan. 2022, 158, 100544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Baper, S.Y. Assessment of Livability in Commercial Streets via Placemaking. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, R.A. Humanization of Street Median Islands: Utilizing Pedestrian Quality Needs Indicators for Saudi Urban Transformation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, V. (Ed.) The Street: A Quintessential Social Public Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, S.A.; Azouz, N.; Hammam, R.; Hendawy, M. UX placemaking towards the inclusion of persons with disabilities in public places in Egypt’s Greater Cairo Region. Cities 2025, 161, 105886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, A.; Maghrabi, A. Role of urban greening strategies for environmental sustainability—A review and assessment in the context of Saudi Arabian megacities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. The evolution of urban mobility: The interplay of academic and policy perspectives. IATSS Res. 2014, 38, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homoud, M.; Jarrar, O.M. Walkability in Riyadh: A comprehensive assessment and implications for sustainable community—Al-Falah case study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S.; Furlan, R.; Awwaad, R. Sustainable Urban Renewal: Planning Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) in Riyadh. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, G.; Mokhtarian, P.; Dijst, M.; Böcker, L. The dynamics of urban metabolism in the face of digitalization and changing lifestyles: Understanding and influencing our cities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 132, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zghoul, S.; Al-Homoud, M. GIS-Driven Spatial Planning for Resilient Communities: Walkability, Social Cohesion, and Green Infrastructure in Peri-Urban Jordan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.; Wood, L.; Foster, S.A.; Giles-Corti, B.; Frank, L.; Learnihan, V. Sense of community and its association with the neighborhood built environment. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, A.; Carlson, N.E.; Yen, I.H.; Michael, Y.L. Neighborhood physical features and relationships with neighbors: Does positive physical environment increase neighborliness? Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgul, E.; Luo, L.; Wei, S.; Pei, C.D. Sense of place or sense of belonging? Developing guidelines for human-centered outdoor spaces in China that citizens can be proud of. Procedia Eng. 2017, 198, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatar, K.M. Rehumanize the Streets and Make Them More Smart and Livable in Arab Cities: Case Study: Tahlia Street; Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G.R.; Blackstaffe, A.; Nettel-Aguirre, A.; Csizmadi, I.; Sandalack, B.; Uribe, F.A.; Rayes, A.; Friedenreich, C.; Potestio, M.L. The independent associations between Walk Score® and neighborhood socioeconomic status, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index among urban adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E. New Urbanism and American Planning: The Conflict of Cultures; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Clemente, O. Introduction. In Measuring Urban Design: Metrics for Livable Places; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, C. Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design; Penguin: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Book, a Division of Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Matan, A. Rediscovering Urban Design Through Walkability. Ph.D. Thesis, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design; Collier Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard, B. Livable Streets 2.0, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Medina-Hernández, E.J.; Guzmán-Aguilar, D.S.; Muñiz-Olite, J.L.; Siado-Castañeda, L.R. The current status of the sustainable development goals in the world. Dev. Stud. Res. 2023, 10, 2163677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, L.E. Ideals versus realities of world poverty and human rights. Metaphilosophy 2022, 53, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Husseiny, M.; Mashaly, I.; Azouz, N.; Sakr, N.; Seddik, K.; Atallah, S. Exploring sustainable urban mobility in Africa-and-MENA universities towards intersectional future research. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 26, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Da Capo Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford University Press. Streetscape. In Oxford English Dictionary; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1933; Available online: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/streetscape_n?tl=true (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Rehan, R.M. Sustainable streetscape as an effective tool in sustainable urban design. HBRC J. 2013, 9, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association of City Transportation Officials. A variety of street users. In Global Street Design Guide; National Association of City Transportation Officials: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://globaldesigningcities.org/publication/global-street-design-guide/designing-streets-people/a-variety-of-street-users/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Zhu, H.; Nan, X.; Yang, F.; Bao, Z. Utilizing the green view index to improve the urban street greenery index system: A statistical study using road patterns and vegetation structures as entry points. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullaney, J.; Lucke, T.; Trueman, S.J. A review of benefits and challenges in growing street trees in paved urban environments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmeligy, D.; Elhassan, Z. The Bio-adaptive algae contribution for sustainable architecture. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 397, No. 1, p. 012007. [Google Scholar]

- The Algae Dome: Growing the Supercrop of the Future. Space10.com. Available online: https://space10.com/projects/the-algae-dome (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Kumar, P.; Corada, K.; Debele, S.E.; Emygdio, A.P.M.; Abhijith, K.; Hassan, H.; Broomandi, P.; Baldauf, R.; Calvillo, N.; Cao, S.-J.; et al. Air pollution abatement from Green-Blue-Grey infrastructure. Innov. Geosci. 2024, 2, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.; Mahdy, M.; Mahmoud, S.; Abdelalim, M.; Ezzeldin, S.; Attia, S. Influence of urban canopy green coverage and future climate change scenarios on energy consumption of new sub-urban residential developments using coupled simulation techniques: A case study in Alexandria, Egypt. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meili, N.; Acero, J.A.; Peleg, N.; Manoli, G.; Burlando, P.; Fatichi, S. Vegetation cover and plant-trait effects on outdoor thermal comfort in a tropical city. Build. Environ. 2021, 195, 107733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, K.; Desouza, K.C.; Fieuw, W.; Watson, R.T.; Yigitcanlar, T. Understanding policy and technology responses in mitigating urban heat islands: A literature review and directions for future research. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armson, D.; Stringer, P.; Ennos, A.R. The effect of tree shade and grass on surface and globe temperatures in an urban area. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Moser, A.; Rötzer, T.; Pauleit, S. Comparing the transpirational and shading effects of two contrasting urban tree species. Urban Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, H.A. Urban sustainability through public architecture. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores, T.R.P.; Ramos, J.S.; Delgado, M.G.; Medina, D.C.; Cerezo-Narvaéz, A.; Domínguez, S.Á. Effect of green infrastructures supported by adaptative solar shading systems on livability in open spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S.; Menteş, Y.; Jamei, E. Investigating the Effect of Blue-Green Infrastructure on Thermal Condition—Case Study: Elazığ, Turkey. Land 2025, 14, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Svenning, J.-C.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, K.; Abrams, J.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Ripple, W.J.; Yu, Z.; Teng, S.N.; Dunn, R.R.; et al. Green spaces provide substantial but unequal urban cooling globally. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, A.; Hystad, P. Evaluating street view exposure measures of visible green space for health research. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checker, M. Wiped out by the “greenwave”: Environmental gentrification and the paradoxical politics of urban sustainability. City Soc. 2011, 23, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Calthorpe, P. Urbanism in the age of climate change. In The City Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 555–568. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, J.M.; Chalfin, A.; Moritz, M.; Wade, B.; Mendlein, A.K.; Braga, A.A.; South, E. Can enhanced street lighting improve public safety at scale? Criminol. Public Policy 2025, 865–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Algarni, F.; Quasim, M.T. (Eds.) Smart Cities: A Data Analytics Perspective; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, B.C.; Farrington, D.P. Effects of improved street lighting on crime. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2008, 4, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, M.; Stevens, Q.; Rueda, S. Taking play seriously in Urban design: The evolution of Barcelona’s superblocks. Space Cult. 2024, 27, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, F. The long road from urban experimentation to the transformation of urban planning practice: The case of tactical urbanism in the city of Barcelona. J. Urban Mobil. 2025, 7, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiran, J.; Grigsby, J.; Gebhardt, V.; Kirby, N.; Leth, U.; Lorenz, F.; Müller, J. Superblocks between theory and practice: Insights from an international e-Delphi process and urban living labs in Vienna and Berlin. Urban Res. Pract. 2025, 18, 622–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Passive cooling of buildings. In Advances in Solar Energy: Volume 16; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 295–344. [Google Scholar]

- Caymaz, G.F.Y.; Kemal Kul, K. An Assessment of Smart Urban Furniture Design: Istanbul Yildiz Technical University Bus Stop Case Study. In Smart Cities: A Data Analytics Perspective; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 297–319. [Google Scholar]

- Alshammari, T.O. New strategic approaches for implementing intelligent streetscape towards livable streets in City of Riyadh. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. PEN 2023, 11, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L.; Pagliaro, M. Solar street lighting: A key technology en route to sustainability. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2017, 6, e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shershneva, E.G.; Alpatova, E.S. Current trends in design of street lights. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1079, No. 3, p. 032006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Zuo, J.; Pullen, S. Effectiveness of pavement-solar energy system–An experimental study. Appl. Energy 2015, 138, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xiao, J.; Yuan, D.; Lu, H.; Xu, S.; Huang, Y. Design and experiment of thermoelectric asphalt pavements with power-generation and temperature-reduction functions. Energy Build. 2018, 169, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Antoni, M.; Saro, O. Massive solar-thermal collectors: A critical literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3666–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyder, F.; Sudhakar, K.; Mamat, R. Solar PV tree design: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, W.; Afzal, R.; Xue, J. “Solar tree”: Exploring new form factors of organic solar cells. Renew. Energy 2014, 72, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, C.N.; Psomopoulos, C.S.; Kehagia, F. A review on the latest trend of Solar Pavements in Urban Environment. Energy Procedia 2019, 157, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.T. Urban greening for new capital cities. A meta review. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 670807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, J. Contribution of ecosystem services to air quality and climate change mitigation policies: The case of urban forests in Barcelona, Spain. In Urban Forests; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Maimaitiyiming, M.; Ghulam, A.; Tiyip, T.; Pla, F.; Latorre-Carmona, P.; Halik, Ü.; Sawut, M.; Caetano, M. Effects of green space spatial pattern on land surface temperature: Implications for sustainable urban planning and climate change adaptation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 89, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat. Urban Planning and Infrastructure in Migration Contexts: Amman Spatial Profile Jordan; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/04/220411-final_amman_profile.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Streetscape Component | Key Livability Functions | Sustainability and SDG Alignment | Innovative Tech/Case Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation | Stress reduction, thermal comfort, noise mitigation, and social cohesion. | SDG 11.7: Universal access to green public spaces. Carbon sequestration. | Algae Domes/PBRS systems; Solar-recharged algae lamps; Roadside tree shading. |

| Furniture | Encouraging “staying” activities, social interaction, and active mobility. | SDG 11.2: Accessible transport systems. Climate responsiveness in arid zones. | Superblocks (Barcelona); Smart/IoT bus stops; PV-powered misting/thermal benches. |

| Lighting | Security, wayfinding, nighttime identity, and psychological well-being. | Energy efficiency via renewables. Enhancement of safety for inclusive use. | Solar Collector Pavements (SCP); LED-integrated cycling lanes (The Netherlands); PV roadways (France). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Metwally, W.M. Streetscapes and Street Livability: Advancing Sustainable and Human-Centered Urban Environments. Sustainability 2026, 18, 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020667

Metwally WM. Streetscapes and Street Livability: Advancing Sustainable and Human-Centered Urban Environments. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020667

Chicago/Turabian StyleMetwally, Walaa Mohamed. 2026. "Streetscapes and Street Livability: Advancing Sustainable and Human-Centered Urban Environments" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020667

APA StyleMetwally, W. M. (2026). Streetscapes and Street Livability: Advancing Sustainable and Human-Centered Urban Environments. Sustainability, 18(2), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020667