China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme Improved the Land Surface Ecological Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Research Objective and Contributions

- (1)

- This study reveals that the carbon ETS had a significant impact on the land surface ecological environment. The previous literature assessing the environmental effects of the ETS has focused on the policy influences on carbon emissions and air quality but has rarely analyzed the impacts on other aspects of ecological quality. We extend the evaluation of carbon ETS from conventional outcomes to a broader ecosystem-based outcome, provide new knowledge for a comprehensive understanding of the environmental effects of the carbon ETS, and provide causal evidence on whether a market-based carbon regulation policy can generate comprehensive ecological co-benefits rather than only improving single environmental indicators. This extension matters because LSEQ integrates multiple dimensions of environmental conditions and is closely linked to long-run welfare and ecosystem resilience.

- (2)

- This study proposes that the implementation of the carbon ETS has been a key contributor to the improvement of China’s land surface ecological quality in recent years. This provides novel insights for a deeper understanding of the dynamics of land eco-environmental status in China. A large amount of the environmental science literature has previously analyzed the determinants of land surface ecological quality. While most of the studies have intensively inspected the impacts of natural factors such as geographic features and climatic conditions or macroeconomic variables such as GDP per capita and population density, fewer have specifically quantified the effect of a particular public policy. This study offers empirical evidence that well-designed public policies can generate beneficial effects.

- (3)

- Our findings provide evidence that a carbon market policy can deliver co-benefits for ecological quality, not only for emissions-related outcomes. This supports the policy rationale of using market-based instruments to advance China’s broader objectives of ecological civilization and high-quality development, and it highlights that the benefits of ETS may be underestimated if evaluation frameworks focus exclusively on emissions or conventional air pollution metrics.

- (4)

- Our analyses yield actionable insights for differentiated policy design by clarifying how the effectiveness of ETS in improving ecological quality may vary with local climatic conditions. This implies that ETS implementation can be complemented by regionally tailored supporting measures—such as ecological restoration, green infrastructure, and coordinated land use management—to maximize ecological co-benefits.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. Impact of Carbon ETS on Land Surface Ecological Quality

2.2.2. Possible Mechanisms

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Empirical Method

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Covariates

3.3. Data Sources

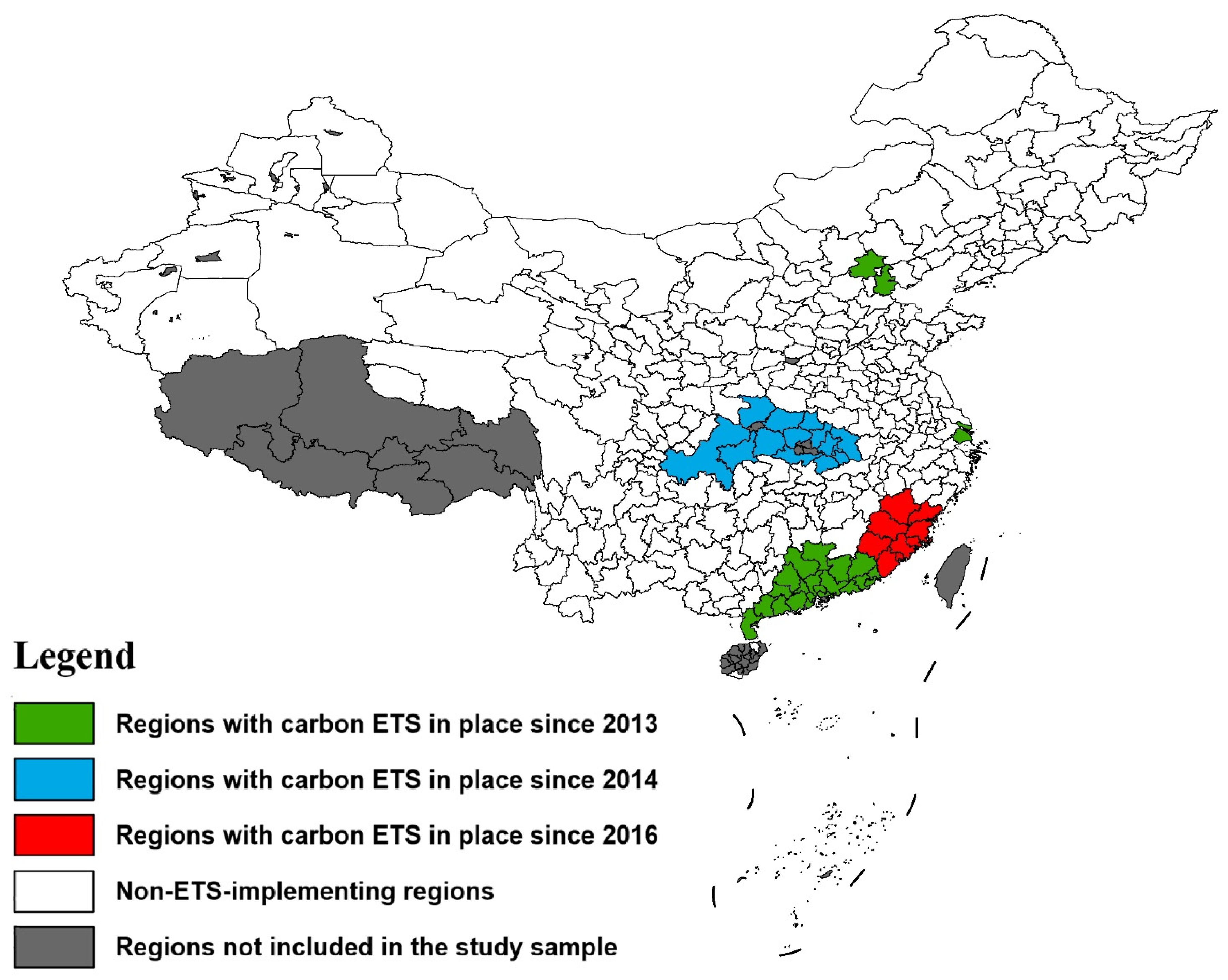

3.4. Sample

4. Main Empirical Results

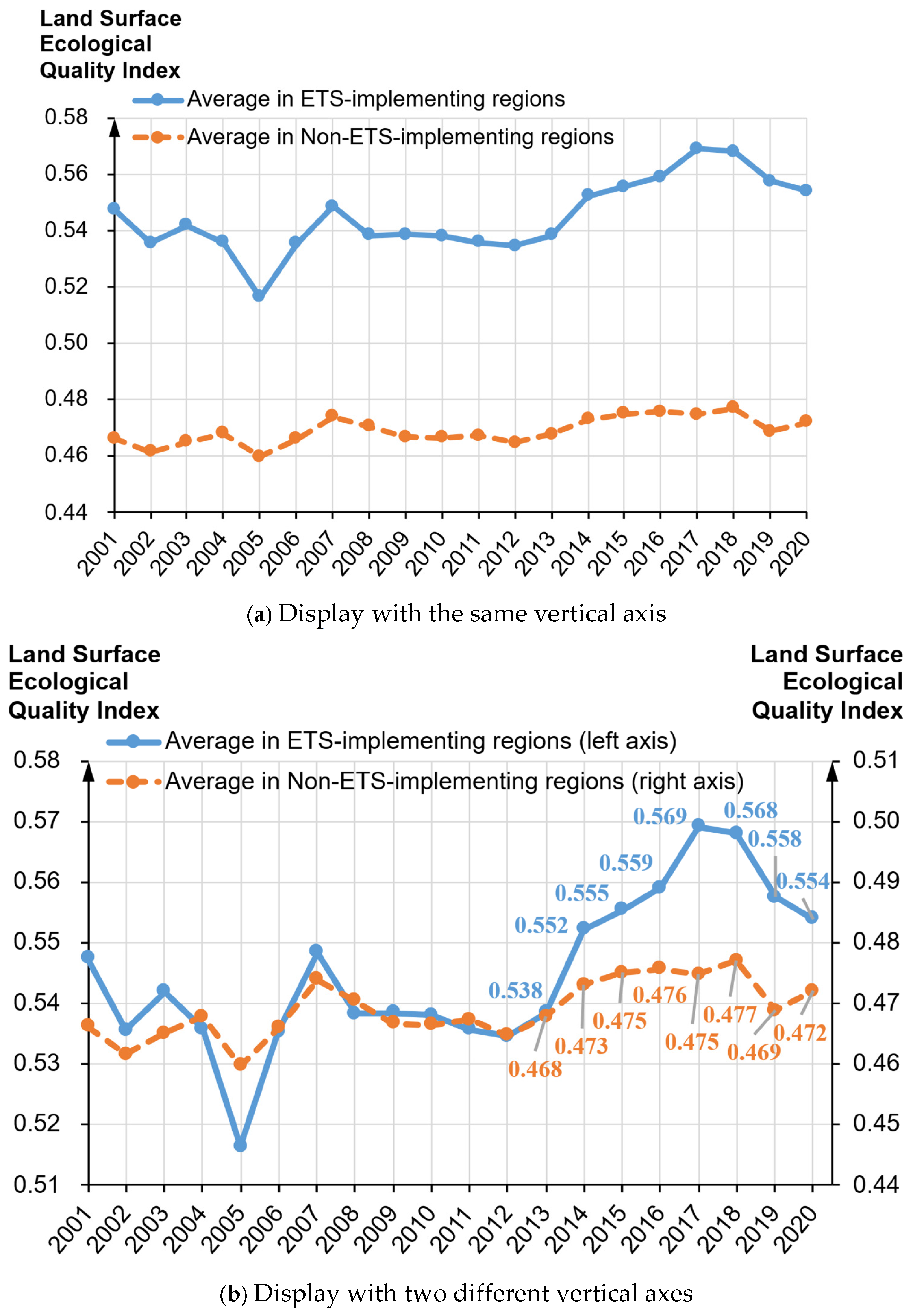

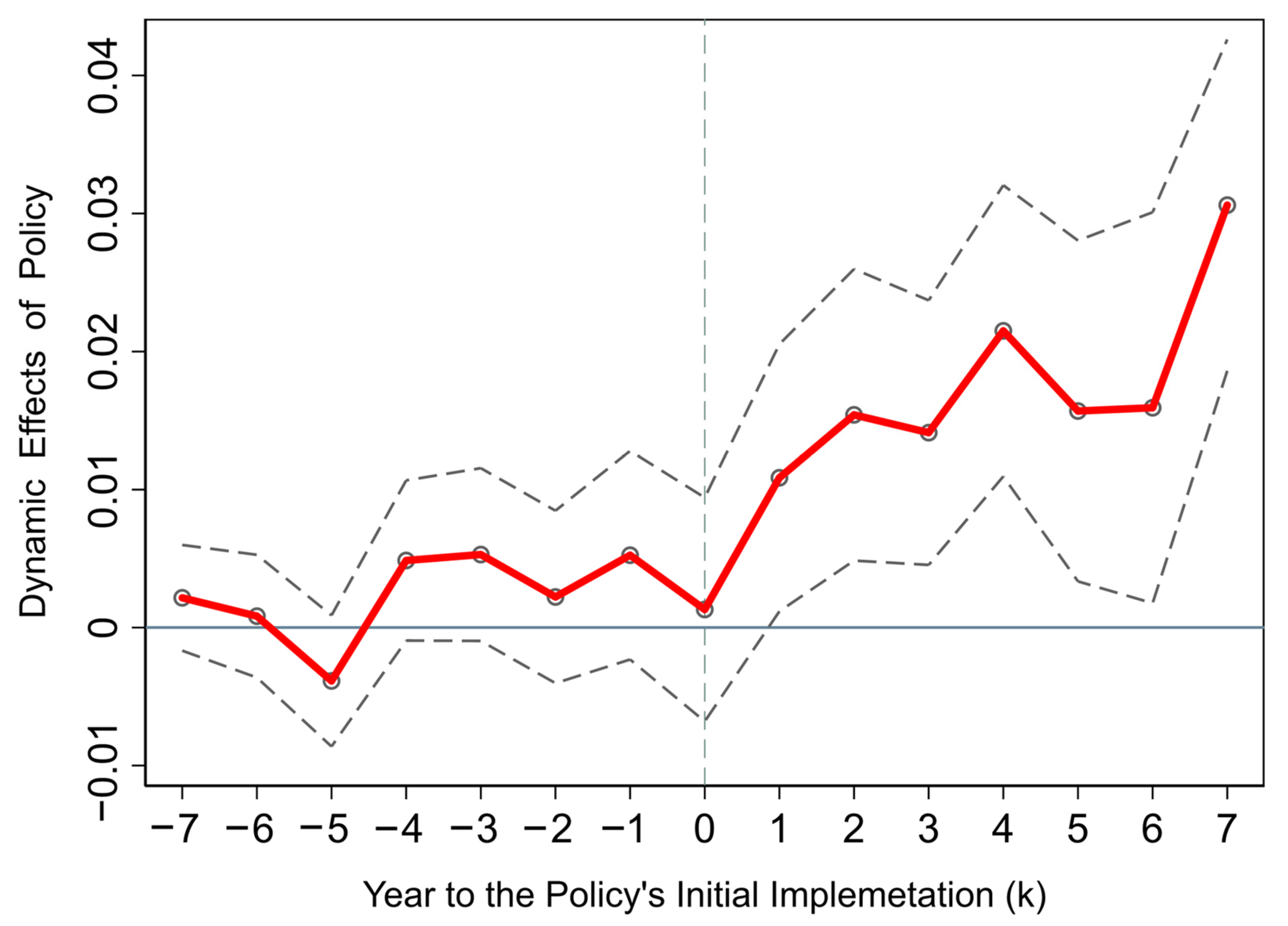

4.1. Positive Effect of the Policy

4.2. Robustness Checks

4.3. Test of the Parallel Trends Assumption

5. Extended Analyses

5.1. Analysis on Mechanisms

5.1.1. Reduction in Pollutant Emissions

5.1.2. Increase in Green Innovation

5.1.3. Change in Land Use

5.1.4. Quantify the Mediation Mechanisms

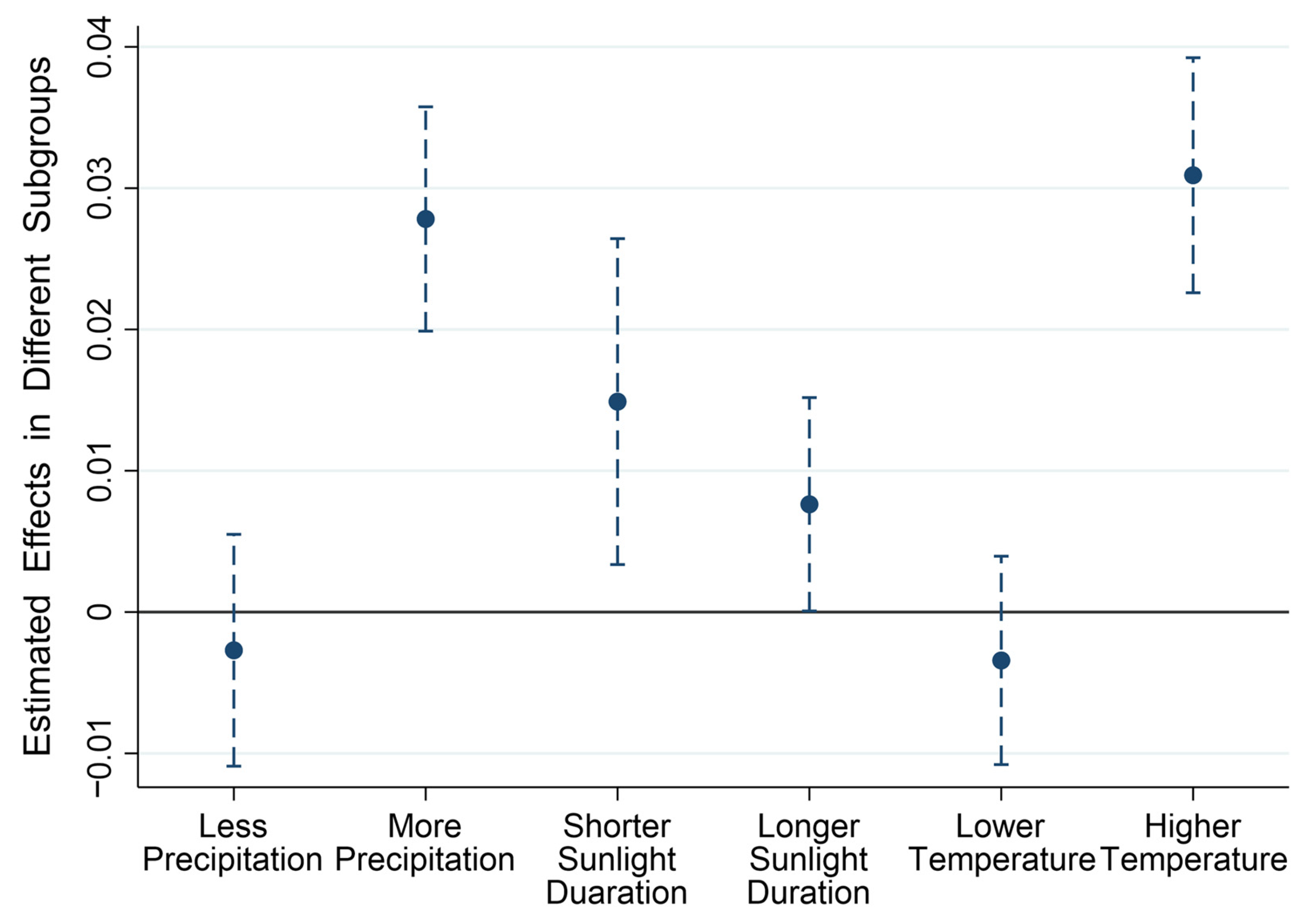

5.2. Analysis on Heterogeneities Contingent on Climatic Conditions

5.3. Analysis on the Possible Spatial Spillover Effect of Policy

6. Conclusions and Discussion

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Discussion

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, C.; Fan, Y.; Bao, C.; Li, G.; Wang, Z.; Sun, S.; Ma, H. China’s improving total environmental quality and environment-economy coordination since 2000: Progress towards sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J. Sustainable development in China: Environmental governance and climate action. China Econ. J. 2024, 17, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, D. Spatio-temporal evolution of ecological environment quality in China from a concept of strong sustainability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 28769–28787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Fathololoumi, S.; Kiavarz, M.; Biswas, A.; Homaee, M.; Alavipanah, S.K. Land Surface Ecological Status Composition Index (LSESCI): A novel remote sensing-based technique for modeling land surface ecological status. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 123, 107375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Mijani, N.; Shorabeh, S.N.; Kazemi, Y.; Ghajari, Y.E.; Arsanjani, J.J.; Kiavarz, M.; Alavipanah, S.K. Assessing the Effect of Urban Growth on Surface Ecological Status Using Multi-Temporal Satellite Imagery: A Multi-City Analysis. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N.C. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Gao, W.; Shi, T.; Liu, X.; Wu, G. Rapid urbanization and policy variation greatly drive ecological quality evolution in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area of China: A remote sensing perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yang, F.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Huang, J.; Wei, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Quantization of the coupling mechanism between eco-environmental quality and urbanization from multisource remote sensing data. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Ho, M.S.; Ma, R.; Teng, F. When carbon emission trading meets a regulated industry: Evidence from the electricity sector of China. J. Public Econ. 2021, 200, 104470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, R. Does carbon emission trading policy has emission reduction effect?—An empirical study based on quasi-natural experiment method. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Qiu, W.; Guo, S. Assessing the effectiveness of emissions trading schemes: Evidence from China. Clim. Policy 2024, 24, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, D.; Zhang, S. Carbon-Trading Pilot Programs in China and Local Air Quality. AEA Pap. Proc. 2021, 111, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jin, H.; Tan, Y. Synergistic effects of a carbon emissions trading scheme on carbon emissions and air pollution: The case of China. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024, 20, 1112–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan-Soo, J.; Li, L.; Qin, P.; Zhang, X. Do CO2 emissions trading schemes deliver co-benefits? Evidence from Shanghai. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Shi, J.; Wan, K.; Chang, T. Carbon trading market policies and corporate environmental performance in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 371, 133683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Quan, Z.; Fang, S.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Fu, Q. Spatiotemporal changes in vegetation coverage and its causes in China since the Chinese economic reform. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 1144–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, P.; Chen, N.; Xu, L.; Dao, D.M.; Dang, D. NDVI Variation and Yield Prediction in Growing Season: A Case Study with Tea in Tanuyen Vietnam. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wang, S.; Watson, A.E.; He, H.; Ye, H.; Ouyang, X.; Li, Y. Pixel-scale historical-baseline-based ecological quality: Measuring impacts from climate change and human activities from 2000 to 2018 in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 313, 114944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Xiao, L.; Guo, Q.; Liu, Y.; Mao, Q.; Kareiva, P. Evidence of causality between economic growth and vegetation dynamics and implications for sustainability policy in Chinese cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Xia, B. A significant increase in the normalized difference vegetation index during the rapid economic development in the Pearl River Delta of China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Han, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Shi, L.; Yan, J. Effects of large-scale land consolidation projects on ecological environment quality: A case study of a land creation project in Yan’an, China. Environ. Int. 2024, 183, 108392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, F.; Duan, P.; Jim, C.Y.; Chan, N.W.; Shi, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Bahtebay, J.; Ma, X. Vegetation cover changes in China induced by ecological restoration-protection projects and land-use changes from 2000 to 2020. Catena 2022, 217, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Rodríguez, L.; Hogarth, N.J.; Zhou, W.; Xie, C.; Zhang, K.; Putzel, L. China’s conversion of cropland to forest program: A systematic review of the environmental and socioeconomic effects. Environ. Evid. 2016, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Xia, F.; Chen, Q.; Huang, J.; He, Y.; Rose, N.; Rozelle, S. Grassland ecological compensation policy in China improves grassland quality and increases herders’ income. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dries, L.; Heijman, W.; Huang, J.; Zhu, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, H. The Impact of Ecological Construction Programs on Grassland Conservation in Inner Mongolia, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hou, M.; Xi, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yao, S. Co-benefits of the National Key Ecological Function Areas in China for carbon sequestration and environmental quality. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1093135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jia, Q.; Xu, X.; Yao, S.; Chen, H.; Hou, X. Contribution of ecological policies to vegetation restoration: A case study from Wuqi County in Shaanxi Province, China. Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, W.; He, J. Spatial and temporal variation of ecological quality in northeastern China and analysis of influencing factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Kasimu, A.; Ma, H.; Eziz, M. Monitoring Multi-Scale Ecological Change and Its Potential Drivers in the Economic Zone of the Tianshan Mountains’ Northern Slopes, Xinjiang, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizizi, Y.; Kasimu, A.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, B. Evaluation of ecological space and ecological quality changes in urban agglomeration on the northern slope of the Tianshan Mountains. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xiu, L.; Yao, X.; Yu, Z.; Huang, X. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors analysis of the eco-quality in the Lanxi urban agglomeration. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yi, L.; Xie, B.; Li, J.; Xiao, J.; Xie, J.; Liu, Z. Analysis of ecological quality changes and influencing factors in Xiangjiang River Basin. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway, B. Difference-in-Differences for Policy Evaluation. In Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics; Klaus, F., Ed.; Zimmermann, 1–61; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, A.P.; Abecasis, D.; Adjeroud, M.; Alonso, J.C.; Amano, T.; Anton, A.; Baldigo, B.P.; Barrientos, R.; Bicknell, J.E.; Buhl, D.A.; et al. Quantifying and addressing the prevalence and bias of study designs in the environmental and social sciences. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksson, A.; de Oliveira, G.M. Impact evaluation using Difference-in-Differences. RAUSP Manag. J. 2019, 54, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M. The Estimation of Causal Effects by Difference-in-Difference Methods. Found. Trends Econom. 2011, 4, 165–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C.; Bilinski, A.; Poe, J. What’s trending in difference-in-differences? A synthesis of the recent econometrics literature. J. Econom. 2023, 235, 2218–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, H. Assessing the impact of emissions trading scheme on low-carbon technological innovation: Evidence from China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixidó, J.; Verde, S.F.; Nicolli, F. The impact of the EU Emissions Trading System on low-carbon technological change: The empirical evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 164, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shang, Y.; Ma, X.; Xia, P.; Shahzad, U. Does Carbon Trading Lead to Green Technology Innovation: Recent Evidence from Chinese Companies in Resource-Based Industries. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 2506–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daresta, B.E.; Italiano, F.; de Gennaro, G.; Trotta, M.; Tutino, M.; Veronico, P. Atmospheric particulate matter (PM) effect on the growth of Solanum lycopersicum cv. Roma plants. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillmann, J.; Aunan, K.; Emberson, L.; Büker, P.; Van Oort, B.; O’Neill, C.; Otero, N.; Pandey, D.; Brisebois, A. Combined impacts of climate and air pollution on human health and agricultural productivity. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 093004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burges, A.; Epelde, L.; Garbisu, C. Impact of repeated single-metal and multi-metal pollution events on soil quality. Chemosphere 2015, 120, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Bing, H.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jin, L. Impacts of atmospheric particulate matter pollution on environmental biogeochemistry of trace metals in soil-plant system: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, A.K.M.; Ibelli-Bianco, C.; Anache, J.A.A.; Coutinho, J.V.; Pelinson, N.S.; Nobrega, J.; Rosalem, L.M.P.; Leite, C.M.C.; Niviadonski, L.M.; Manastella, C.; et al. Pollution threat to water and soil quality by dumpsites and non-sanitary landfills in Brazil: A review. Waste Manag. 2021, 131, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Arias, A.; Martín-Peinado, F.J.; Parviainen, A. Effect of parent material and atmospheric deposition on the potential pollution of urban soils close to mining areas. J. Geochem. Explor. 2023, 244, 107131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Woodward, R.T.; Zhang, Y. Has Carbon Emissions Trading Reduced PM2.5 in China? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 6631–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calel, R.; Dechezleprêtre, A. Environmental Policy and Directed Technological Change: Evidence from the European Carbon Market. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2016, 98, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ye, F.; Li, Y.; Chang, C. How will the Chinese Certified Emission Reduction scheme save cost for the national carbon trading system? J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 244, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lin, B. Impact of introducing Chinese certified emission reduction scheme to the carbon market: Promoting renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boori, M.S.; Choudhary, K.; Paringer, R.; Kupriyanov, A. Spatiotemporal ecological vulnerability analysis with statistical correlation based on satellite remote sensing in Samara, Russia. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, 112138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Kiavarz, M.; Homaee, M.; Arsanjani, J.J.; Alavipanah, S.K. A novel method to quantify urban surface ecological poorness zone: A case study of several European cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbalaei Saleh, S.; Amoushahi, S.; Gholipour, M. Spatiotemporal ecological quality assessment of metropolitan cities: A case study of central Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, S.; Alavipanah, S.K.; Konyushkova, M.; Mijani, N.; Fathololomi, S.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Homaee, M.; Hamzeh, S.; Kakroodi, A.A. A Remotely Sensed Assessment of Surface Ecological Change over the Gomishan Wetland, Iran. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Tang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Sheng, T.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, R.; Shifaw, E.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; et al. Study on Regional Eco-Environmental Quality Evaluation Considering Land Surface and Season Differences: A Case Study of Zhaotong City. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, C.; Liu, N.; He, X.; Ye, Q.; Deng, Y.; Zou, J. Ecological quality of a global geopark at different stages of its development: Evidence from Xiangxi UNESCO Global Geopark, China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 46, e02617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; He, T.; Zhang, M.; Wu, C. Spatiotemporal variations in the eco-health condition of China’s long-term stable cultivated land using Google Earth Engine from 2001 to 2019. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 149, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kahn, M.E.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. The consequences of spatially differentiated water pollution regulation in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 88, 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Yang, L. Haze Governance, Local Competition and Industrial Green Transformation. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 118–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, S. Financial Development, Environmental Regulations and Green Economic Transition. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 47, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fezzi, C.; Harwood, A.R.; Lovett, A.A.; Bateman, I.J. The environmental impact of climate change adaptation on land use and water quality. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Egidi, E.; Guirado, E.; Leach, J.E.; Liu, H.; Trivedi, P. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. The effectiveness of China’s regional carbon market pilots in reducing firm emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2109912118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, K. Emissions trading system (ETS) implementation and its collaborative governance effects on air pollution: The China story. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, X.; Yan, X.; Bai, T.; Xu, D. Impact of China’s Rural Land Marketization on Ecological Environment Quality Based on Remote Sensing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Peng, X.; Tang, R.; Geng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, D.; Bai, T. Spatial and Temporal Variation Characteristics of Ecological Environment Quality in China from 2002 to 2019 and Influencing Factors. Land 2024, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Yang, C. Analyzing ecological environment change and associated driving factors in China based on NDVI time series data. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Wu, C. BCI: A biophysical composition index for remote sensing of urban environments. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 127, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, W. Dynamic analysis of ecological environment combined with land cover and NDVI changes and implications for sustainable urban–rural development: The case of Mu Us Sandy Land, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Cao, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Myneni, R.B.; Piao, S. Spatiotemporally consistent global dataset of the GIMMS Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (PKU GIMMS NDVI) from 1982 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 4181–4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusyak, K.; Jaravel, X.; Spiess, J. Revisiting Event-Study Designs: Robust and Efficient Estimation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2024, 91, 3253–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhangelsky, D.; Athey, S.; Hirshberg, D.A.; Imbens, G.W.; Wager, S. Synthetic Difference-in-Differences. Am. Econ. Rev. 2021, 111, 4088–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, D.; Dube, A.; Lindner, A.; Zipperer, B. The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs. Q. J. Econ. 2019, 134, 1405–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chaisemartin, C.; D’Haultfœuille, X. Two-Way Fixed Effects Estimators with Heterogeneous Treatment Effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2964–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.K.; Kwok, S.S. The PCDID Approach: Difference-in-Differences When Trends Are Potentially Unparallel and Stochastic. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2022, 40, 1216–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, A.; Girardi, D.; Jordà, Ò.; Taylor, A.M. A local projections approach to difference-in-differences. J. Appl. Econom. 2025, 40, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J. Two-stage differences in differences. Work. Pap. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Abraham, S. Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Two-way fixed effects, the two-way mundlak regression, and difference-in-differences estimators. Empir. Econ. 2025, 69, 2545–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Number of Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EcologicalQuality | 5222 | 0.482 | 0.139 | 0.035 | 0.812 |

| CO2ETS | 5222 | 0.063 | 0.243 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Precipitation | 5222 | 6.684 | 0.710 | 3.290 | 7.923 |

| Sunlight | 5222 | 7.582 | 0.272 | 6.623 | 8.129 |

| Temperature | 5222 | 13.154 | 6.006 | −7.822 | 25.726 |

| GDPPerCapita | 5222 | 9.858 | 0.686 | 7.622 | 11.723 |

| PopulationDensity | 5222 | 5.410 | 1.344 | −0.379 | 8.275 |

| IndustrialStructure | 5222 | 0.145 | 0.093 | 0.000 | 0.670 |

| FinancialDevelopment | 5222 | 0.876 | 0.520 | 0.075 | 4.487 |

| TradeOpenness | 5222 | 0.214 | 0.583 | 0.000 | 17.176 |

| GovernmentSize | 5222 | 0.220 | 0.200 | 0.043 | 3.581 |

| HighSpeedRail | 5222 | 0.353 | 0.478 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| RoadDensity | 5222 | −0.355 | 0.857 | −5.818 | 1.650 |

| PublicHealth | 5222 | 1.385 | 0.446 | −0.088 | 2.704 |

| Afforestation | 5222 | 0.119 | 0.112 | 0.000 | 1.241 |

| Variables | Baseline Estimation Result | Robustness Checks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use Winsorized Sample | Use NDVI to Measure Ecological Quality | Use PSM-DID Estimation | Use Imputation DID Estimation | ||

| (i) | (ii) | (iii) | (iv) | (v) | |

| CO2ETS | 0.0113 ** | 0.0119 *** | 0.00449 * | 0.00854 * | 0.0177 *** |

| [0.004] | [0.004] | [0.002] | [0.004] | [0.003] | |

| Precipitation | 0.00620 ** | 0.00691 ** | 0.0166 *** | 0.00179 | 0.00933 *** |

| [0.002] | [0.002] | [0.001] | [0.002] | [0.002] | |

| Sunlight | 0.0218 *** | 0.0196 *** | −0.0217 *** | 0.0263 *** | 0.0189 *** |

| [0.005] | [0.005] | [0.003] | [0.005] | [0.005] | |

| Temperature | −0.0216 *** | −0.0212 *** | 0.00453 *** | −0.0242 *** | −0.0222 *** |

| [0.002] | [0.002] | [0.001] | [0.002] | [0.002] | |

| GDPPerCapita | 0.0115 ** | 0.00827 * | 0.00455 | 0.0108 ** | 0.0146 *** |

| [0.004] | [0.004] | [0.003] | [0.004] | [0.004] | |

| PopulationDensity | 0.00913 | 0.00604 | 0.00191 | 0.0114 * | 0.00596 |

| [0.005] | [0.004] | [0.003] | [0.006] | [0.003] | |

| IndustrialStructure | 0.0714 ** | 0.0529 * | 0.0173 | 0.0406 | 0.0688 ** |

| [0.022] | [0.022] | [0.012] | [0.026] | [0.022] | |

| FinancialDevelopment | −0.00799 *** | −0.00961 *** | −0.00024 | −0.00884 *** | −0.00831 *** |

| [0.002] | [0.002] | [0.002] | [0.002] | [0.002] | |

| TradeOpenness | 0.00409 ** | 0.0142 ** | 0.00141 ** | 0.00394 * | 0.00412 ** |

| [0.001] | [0.005] | [0.000] | [0.002] | [0.001] | |

| GovernmentSize | −0.00515 | −0.0106 | −0.000652 | 0.0114 | −0.00566 |

| [0.004] | [0.007] | [0.003] | [0.010] | [0.004] | |

| HighSpeedRail | 0.00215 | 0.00191 | 0.00165 | 0.0018 | 0.00239 |

| [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | [0.001] | |

| Road | −0.00331 | 0.000225 | −0.00189 | −0.00408 | −0.00147 |

| [0.002] | [0.003] | [0.002] | [0.002] | [0.002] | |

| PublicHealth | 0.0121 *** | 0.0110 ** | 0.0116 *** | 0.00942 * | 0.00613 |

| [0.003] | [0.003] | [0.002] | [0.004] | [0.003] | |

| Afforestation | −0.0254 | −0.0264 | 0.0252 * | −0.0440 ** | −0.0111 |

| [0.013] | [0.014] | [0.010] | [0.015] | [0.012] | |

| Control other policies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of cities | 328 | 328 | 328 | 309 | 328 |

| Number of observations | 5222 | 5222 | 5221 | 4701 | 5222 |

| Within R2 | 0.320 | 0.314 | 0.677 | 0.359 | - |

| Variables | Pollutant Emissions | Green Innovation | Proportion of Lands with Vegetation Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| (i) | (ii) | (iii) | |

| CO2ETS | −0.0746 *** | 0.218 ** | 0.00555 * |

| [0.010] | [0.079] | [0.003] | |

| Covariates | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| City-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of cities | 328 | 328 | 328 |

| Number of observations | 5222 | 5222 | 5222 |

| Within R2 | 0.799 | 0.863 | 0.137 |

| Effects | Pollutant Emissions | Green Innovation | Proportion of Lands with Vegetation Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| (i) | (ii) | (iii) | |

| Indirect effect | 0.00103 ** | 0.00018 * | 0.00073 *** |

| [0.00025] | [0.00009] | [0.00010] | |

| Direct effect | 0.01025 *** | 0.01110 *** | 0.01055 *** |

| [0.00199] | [0.00189] | [0.00185] | |

| Total effect | 0.01129 *** | 0.01129 *** | 0.01129 *** |

| [0.00194] | [0.00194] | [0.00194] |

| Variables | Policy Spillover Effect on Adjacent Cities | Policy Spillover Effect on Cities in Adjacent Provinces |

|---|---|---|

| (i) | (ii) | |

| CO2ETS | 0.0121 *** | 0.0131 *** |

| [0.004] | [0.004] | |

| AdjacentCities | 0.0043 | - |

| [0.003] | - | |

| AdjacentProvinces | - | 0.0029 |

| - | [0.002] | |

| Covariates | Yes | Yes |

| City-fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Year-fixed effects | Yes | Yes |

| Number of cities | 328 | 328 |

| Number of observations | 5222 | 5222 |

| Within R2 | 0.321 | 0.321 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, D.; Dong, D. China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme Improved the Land Surface Ecological Quality. Sustainability 2026, 18, 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020616

Zheng D, Dong D. China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme Improved the Land Surface Ecological Quality. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020616

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Diwei, and Daxin Dong. 2026. "China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme Improved the Land Surface Ecological Quality" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020616

APA StyleZheng, D., & Dong, D. (2026). China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Scheme Improved the Land Surface Ecological Quality. Sustainability, 18(2), 616. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020616