Collaborative Supervision for Sustainable Governance of the Prepared Food Industry in China: An Evolutionary Game and Markov Chain Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Development of the Prepared Food Industry: From Rapid Expansion to Sustainable Governance

2.2. Collaborative Food Safety Governance: From Government Dominance to Multi-Actor Participation

2.3. Evolutionary Games in Regulatory Studies: From Static Equilibrium to Behavioral Dynamics

2.4. Markov Chain Applications in Risk Evolution and Governance: Capturing Random Transitions and Long-Run Stability

2.5. Summary and Research Contributions

- (1)

- Governance Contribution

- (2)

- Methodological Contribution

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Justification

3.1.1. Rationale for Using an Evolutionary Game Model

3.1.2. Reasons for Not Employing System Dynamics, Dynamic System Models, or ABM

3.1.3. Necessity of Incorporating the Markov Chain Method

3.1.4. Integrated Advantages of the Methodological Framework

3.2. Definition of the Three Actors and Their Strategy Sets

3.3. Replicator Dynamic Equations and System Stability Analysis

- (1)

- Replicator Dynamic Equation for the Government

- (2)

- Replicator Dynamic Equation for Firms

- (3)

- Replicator Dynamic Equation for Consumers

3.4. Markov Chain Modeling and State Transition Dynamics

4. Dynamic Evolution Results and Policy Simulation Analysis

4.1. Markov Chain Simulation Results and State Transitions

- (1)

- Basic Principles and Equation Derivation

- (2)

- Parameter Settings and Simulation Procedure

- (3)

- Simulation Results and Interpretation of Stationarity

- (4)

- Simulation-Based Inferences and Mechanism Interpretation

- (5)

- Practical Implications

4.2. Parameter Sensitivity and Key Influencing Factors

4.2.1. Setting the Additional Cost for Corporate Integrity Management

4.2.2. Setting the Government Regulatory Cost Parameter

4.2.3. Setting of Parameter for Government Regulatory Intensity

4.2.4. Setting of Penalty Parameter

4.2.5. Setting of Consumer Compensation Parameter

4.2.6. Setting the Cost of Consumer Complaints

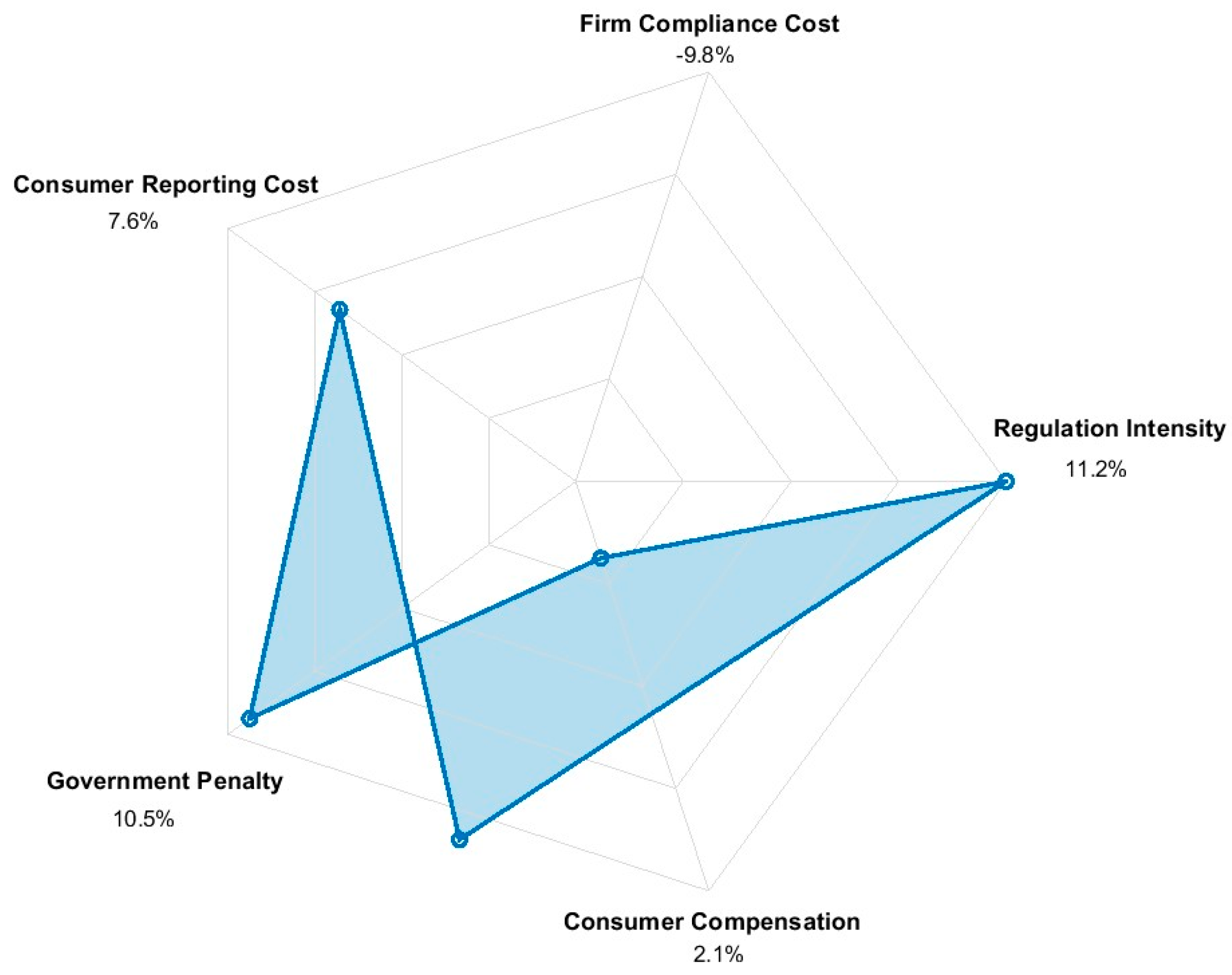

4.2.7. Integrated Sensitivity Framework

- (1)

- Variation in Regulatory Costs (Figure 7a)

- (2)

- Variation in Firms’ Compliance Costs (Figure 7b)

- (3)

- Variation in Consumers’ Reporting Costs (Figure 7c)

- (4)

- Variation in Government Regulatory Intensity (Figure 7d)

- (5)

- Variation in Penalty Levels (Figure 7e)

- (6)

- Variation in Consumer Compensation (Figure 7f)

- (7)

- Overall Conclusions and Practical Implications

- (1)

- Reducing regulatory costs for both government agencies and consumers to alleviate supervision burdens;

- (2)

- Strengthening regulatory enforcement and penalty mechanisms to establish a long-term, stable system of incentives and constraints;

- (3)

- Building a coordinated regulatory framework involving government, firms, and consumers to achieve a dynamic balance between regulatory effectiveness and sustainable industry development.

4.2.8. Cross-Parameter Interaction Analysis

4.3. Policy Scenario Simulation and Comparison of Regulatory Performance

- (1)

- Government-Only Active Regulation

- (2)

- Consumer-Only Active Reporting

- (3)

- Government–Consumer Collaborative Regulation

- (4)

- Stakeholder cost–benefit decomposition and burden-sharing under alternative scenarios

- (5)

- Robustness check with heterogeneous actor characteristics.

- (6)

- Comprehensive comparison and conclusionThe dynamic evolutionary results across the three regulatory scenarios reveal several consistent patterns and provide clear policy implications for the governance of the prepared-food supply chain.

- (1)

- Government-only regulation can strengthen oversight in the short run, but it is difficult to sustain. This regime requires substantial administrative resources and tends to suffer from delayed information feedback and persistent enforcement pressure. Over time, these structural constraints undermine long-run stability and limit the formation of a durable governance arrangement.

- (2)

- Consumer-only monitoring relies primarily on individuals’ willingness to report and their tolerance for reporting costs. Such participation is inherently fragile and subject to behavioral volatility, especially when institutional support is weak. As a result, consumer-only monitoring cannot reliably maintain quality and safety oversight in a complex, multi-stage supply chain.

- (3)

- Government–consumer co-regulation outperforms the other regimes by combining the institutional capacity of government enforcement with the distributed information advantages of consumers. This complementarity improves feedback speed and transparency, thereby accelerating convergence and strengthening long-run stability. Importantly, the added stakeholder-level analysis clarifies that collaboration does not eliminate supervision costs; rather, it redistributes the burden in a more balanced manner. As reported in Table 7 and visualized in Figure 9, the government-only regime places the overwhelming share of the explicit oversight burden on the government, whereas co-regulation shifts part of the information-acquisition effort to consumer reporting while keeping government enforcement as a credible backbone. This burden-sharing structure helps sustain deterrence and supports stable system performance.

- (4)

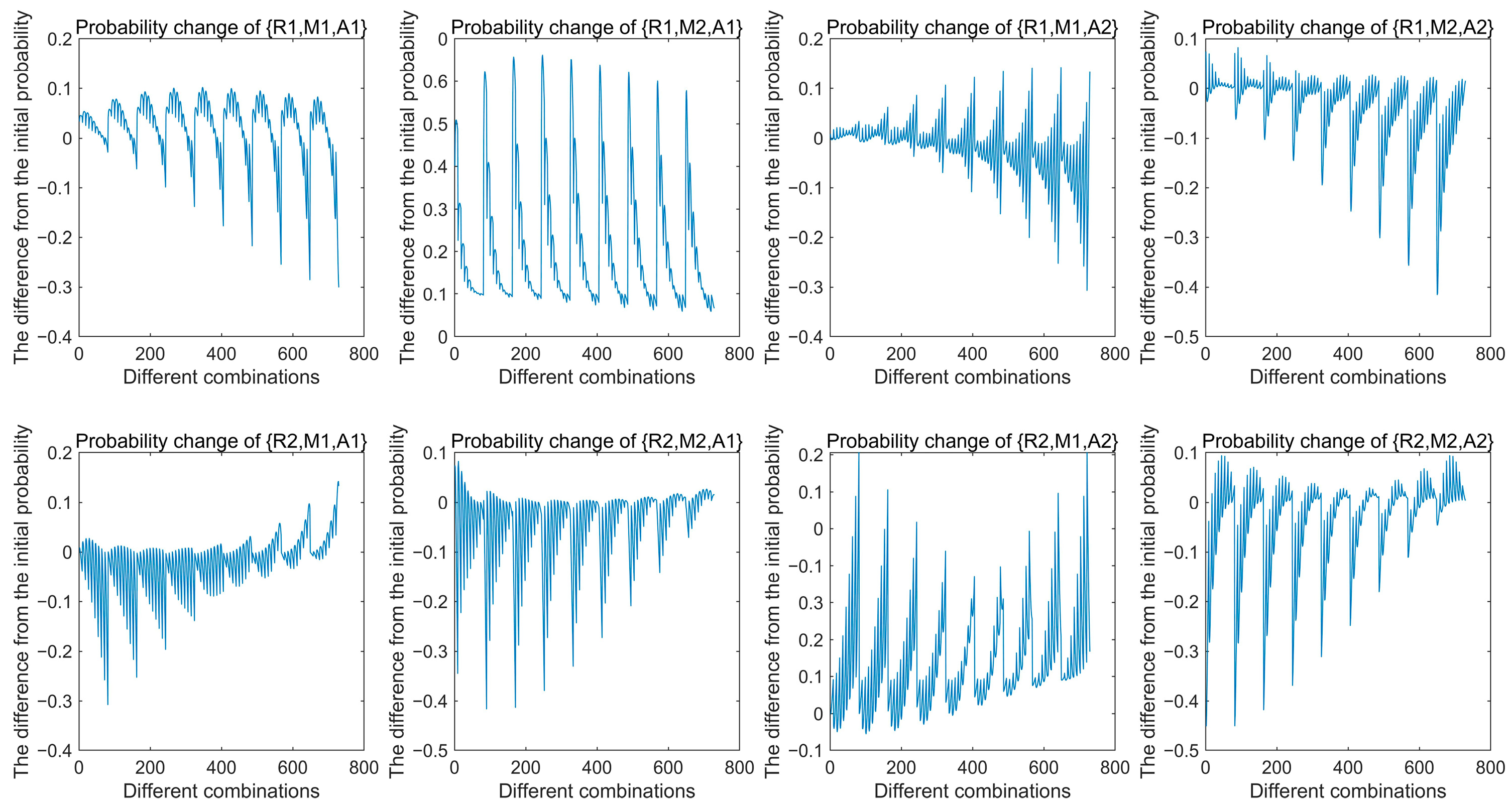

- Robustness to heterogeneous actor characteristics. The scenario-comparison conclusions are not driven by a specific homogeneous calibration. As shown in Figure 10, each trajectory corresponds to one simulation with a randomly drawn heterogeneous parameter set and a random initial state. The trajectories consistently converge toward the same attractor (near the boundary equilibrium identified in the baseline analysis), indicating that the qualitative evolutionary stability and the relative ranking of policy scenarios remain robust under heterogeneity in government enforcement intensity, firm compliance incentives, and consumer reporting preferences.

4.4. Policy Effect Elasticity Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Existing Studies

5.2. Contributions to the Regulatory System and Sustainable Governance

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

- (1)

- Simplifying assumptions and lack of heterogeneity.

- (2)

- Absence of networked interaction structures.

- (3)

- Theoretical rather than empirical calibration of transition probabilities.

- (4)

- Lack of multi-objective policy optimization.

- (5)

- Static payoff assumptions without learning, belief updating, or reputation effects

5.4. Policy Implications and Practical Recommendations

5.5. Practical Implementation and Transferability Across Regulatory Contexts

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings

- (1)

- Collaborative supervision strengthens long-run compliance. In the collaborative regulation setting, joint government enforcement and consumer reporting accelerate convergence toward a stable outcome and increase the long-run likelihood of firm compliance (exceeding 0.55 in the baseline calibration), while reducing the prevalence of opportunistic behavior.

- (2)

- Cost frictions materially shape governance stability. Higher enforcement costs, higher firm compliance costs, or higher consumer reporting costs shift actors toward less active strategies and move the system away from high-compliance stability regions, weakening the effectiveness of supervision.

- (3)

- Deterrence depends on policy coherence. Strong governance performance arises when enforcement intensity and penalty severity are jointly aligned. Adjusting either instrument in isolation produces weaker effects than coordinated policy packages that raise expected deterrence while managing supervision burdens.

- (4)

- Collaborative regulation is robust under uncertainty. The Markov-chain results indicate rapid convergence to a stationary distribution (approximately seven iterations in the baseline setting) and stable long-run behavior under stochastic disturbances, supporting the resilience of the collaborative governance mechanism.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qaim, M. Globalisation of agrifood systems and sustainable nutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. National Economy Witnessed Momentum of Recovery with Positive Developments in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202401/t20240117_1946605.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. 2023 Central No. 1 Document: Opinions on Doing a Good Job in Comprehensively Promoting Rural Revitalization in 2023 (Full Text). 2023. Available online: https://www.lswz.gov.cn/html/xinwen/2023-02/13/content_273655.shtml (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- State Administration for Market Regulation and Other Five Central Departments. Notice on Strengthening Food Safety Supervision of Prepared Dishes and Promoting High-Quality Development of the Industry. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202403/content_6940806.htm (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Ali, I.; Nagalingam, S.; Gurd, B. A resilience model for cold chain logistics of perishable products. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 922–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCTV News. CCTV “3·15” Investigation Exposed Improperly Handled “Neck Meat” Used in Meicai Kou Rou Prepared Dishes. CCTV News. 2024. Available online: https://news.cctv.com/2024/03/16/ARTImAYOzmwGkrGNlMIhPE0m240316.shtml (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR). Press Conference Transcript: “Conducting Full-Chain Sampling Inspection and Strengthening Full-Chain Supervision” (Five Typical Food Safety Cases Released). 2025. Available online: https://www.fxhz.gov.cn/content/2025/1023493.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR). Announcement on Food Safety Supervision Sampling Inspection by Market Regulation Departments in the First Quarter of 2024 (No. 16, 2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.bypc.gov.cn/zfxxgk/bmdwxzjd/bmdw/qscjdglj/fdzdgknr/ssjgk/art/2024/art_e4763cac0e9f4ef391ffd3fe697d53cb.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Dai, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Hu, W. Food safety risk behavior and social co-governance in the food supply chain. Food Control 2023, 152, 109832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/guidance-regulation-food-and-dietary-supplements/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- European Parliament and of the Council. Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 on official controls and other official activities performed to ensure the application of food and feed law, rules on animal health and welfare, plant health and plant protection products (Official Controls Regulation). Off. J. Eur. Union 2017, L 95, 1–142. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/625/oj/eng (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Strategy for Food Safety 2022–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/food-safety/who-global-strategy-food-safety-2022-2030.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Principles and Guidelines for the Assessment and Use of Voluntary Third-Party Assurance Programmes; CXG 93-2021; FAO/WHO: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/es/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXG%2B93-2021%252FCXG_093e.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Henson, S. Lessons from Private Food Safety Standards as a Governance Mechanism for Agri-Food Value Chains; Working Paper (World Development Report 2025 Background Paper); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/360e477d92038c69be582a62c16c0394-0050062025/original/Spencer-Henson-Private-food-standards.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Mutukumira, A.N.; Chen, H. Food safety governance in China: From supervision to coregulation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 4127–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y. Food safety governance in China: Change and continuity. Food Control 2019, 106, 106752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chen, T.; Pan, J. Evolutionary dynamics of health food safety regulatory information disclosure from the perspective of consumer participation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3958–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, E.; Xiang, S.; Yang, Y.; Sethi, N. A stochastic and time-delay evolutionary game of food safety regulation under central government punishment mechanism. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajihashemi, M.; Aghababaei Samani, K. Multi-strategy evolutionary games: A Markov chain approach. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fudenberg, D.; Imhof, L.A. Imitation processes with small mutations. J. Econ. Theory 2006, 131, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J. Evolutionary Game and Simulation Analysis of Food Safety Regulation under Time Delay Effect. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, J.; Dai, X.; Chen, X. Safe Food Supply Chain as Health Network: An Evolutionary Game Analysis of Behavior Strategy for Quality Investment. Inquiry 2024, 61, 00469580241244728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Xu, L.; Sun, Q.; Guo, M. Stochastic Evolutionary Game Analysis of Food Cooperation among Countries along the Belt and Road from the Perspective of Food Security. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1238080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fan, X.; Dai, M. Evolution and Comparison of Food Safety Governance in China—Based on DTM Model. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1640660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xu, Y. Evolutionary Game Analysis of the Quality of Agricultural Products in Supply Chain. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhan, K. Research on the Evolutionary Game of Quality Governance of Geographical Indication Agricultural Products in China: From the Perspective of Industry Self-Governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iiMedia Research. iiMedia Research|2022 China Pre-cooked Food Industry Development White Paper (Download Available). 2023. Available online: https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/92015.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- iiMedia Research. iiMedia Research|2023 China Pre-cooked Food Industry Development Blue Book (Download Available). 2024. Available online: https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/99463.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- iiMedia Research. iiMedia Research|2024-2025 China Pre-Cooked Food Industry Development Blue Book (Download Available). 2025. Available online: https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/106595.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Tan, Z.; Li, S.; Jiang, L.W. Application of HACCP System in Marinated Quail Egg Production. J. Food Saf. Qual. 2013, 4, 609–612. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Bi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, B. Inheritance and innovation of Chinese prepared dishes industry. J. Chin. Inst. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Sun, L.; Li, H.; Cai, Y.; Guan, R.; Tian, Q. Research Progress, Problems, and Suggestions on the Standard System of Prepared Dish in China. Storage Process 2024, 24, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G.; Posthuma, A.C.; Rossi, A. Disruptions in Global Value Chains—Continuity or Change for Labour Governance? Int. Labour Rev. 2021, 160, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; Soon, J.M. Food Safety, Food Fraud, and Food Defense: A Fast Evolving Literature. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, R823–R834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R. Food System Transformation: Urban Perspectives. Cities 2023, 134, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Sun, Y.; Du, H.; Jiang, X. Research on safety risk control of prepared foods from the perspective of supply chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, M.M.; Chang, Y.S. Traceability in a food supply chain: Safety and quality perspectives. Food Control 2014, 39, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y. Explaining Chinese consumers’ continuous consumption intention toward prepared dishes: The role of perceived risk and trust. Foods 2023, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Chen, G.; Li, F.; Miao, G.; Wu, Y. Decoding consumer-perceived risks in China’s C-end online purchasing pre-made dishes: A Quality safety risk identification model based on grounded theory. J. Food Prot. 2025, 88, 100522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z. Governance of Food Safety in China’s Pre-Made Dishes Industry: Legal Reforms, Policy Strategies, and International Perspectives. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1702278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhang, M.; Bhandari, B. Recent development in the application of alternative sterilization technologies to prepared dishes: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Ju, R.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Wang, H. Advances in Prepared Dish Processing Using Efficient Physical Fields: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 64, 4031–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, M.; Law, C.L.; Luo, Z. 3D Printing Technology for Prepared Dishes: Printing Characteristics, Applications, Challenges and Prospects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 11437–11453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.J.; Huang, Y.X. Market Order, market supervision and platform governance in the digital age. Econ. Res. J. 2021, 56, 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Yin-He, S.; Qian, Y.; Zhi-Yu, S.; Chun-Zi, W.; Zi-Yun, L. Method of reaching consensus on probability of food safety based on the integration of finite credible data on block chain. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 123764–123776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Guo, L. Research on Food Safety Supervision Dilemma and Legal Regulation of Prepared Dishes. Storage Process 2024, 24, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rouvière, E.; Royer, A. Public–Private Partnerships in Food Industries: A Road to Success? Food Policy 2017, 69, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Koos, S.; Shore, J. Co-Governing Common Goods: Interaction Patterns of Private and Public Actors. Policy Soc. 2016, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative platforms as a governance strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizerhof, C.; Bieling, C. Of innovators, enablers and change agents: Disentangling actors and their roles in agri-food transition processes. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2024, 73, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FSMA Final Rule for Preventive Controls for Human Food (Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma/fsma-final-rule-preventive-controls-human-food (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Principles and Guidelines for the Assessment and Use of Voluntary Third-Party Assurance Programmes (CXG 93-2021). FAO Knowledge Repository. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/24c0eea5-900f-41c5-be96-39b6bad9d5fc (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Grunert, K.G.; Wills, J.M. A review of European research on consumer response to nutrition information on food labels. J. Public Health 2007, 15, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G. Publication trends and green cosmetics buying behaviour: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Research on the Transformation of Chinese Government Regulation in the Digital Economy Era. Manag. World 2024, 40, 110–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, L. Game Strategies of Product Quality Collaborative Supervision Driven by Social Media. China Soft Sci. 2024, 2, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y. Serial Inventory Systems with Markov-Modulated Demand: Derivative Bounds and Insights. Oper. Res. 2017, 65, 1231–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, W.; Pang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M. Study on the evolutionary game of central government and local governments under central environmental supervision system. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Ma, J. The evolutionary mechanism of haze collaborative governance: Novel evidence from a tripartite evolutionary game model and a case study in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Chen, W.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Sun, S. Regulation Mechanism of Live-streaming E-commerce Based on Evolutionary Gametheory. J. Manag. Sci. China 2023, 26, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xing, L.; Li, W. A Risk-Averse Inventory Decision-Making Model with Quality Incompleteness. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 32, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kang, Y.; Petropoulos, F. Combining probabilistic forecasts of intermittent demand. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 315, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrdoust, F.; Noorani, I.; Kanniainen, J. Valuation of option price in commodity markets described by a Markov-switching model: A case study of WTI crude oil market. Math. Comput. Simul. 2024, 215, 228–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Wu, W.; Yan, Z.; Su, X.; Zhen, X. Disruption risk propagation in supply chain network based on Markov and epidemic model. J. Ind. Eng. 2023, 37, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Two views of supply chain resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 4031–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosov, A.; Borisov, A. Comparative Study of Markov Chain Filtering Schemas. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugden, R. The Evolutionary Turn in Game Theory. J. Econ. Methodol. 2001, 8, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, E. Evolving Game Theory. J. Econ. Surv. 1997, 11, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clempner, J.B. On Lyapunov Game Theory Equilibrium: Static and Dynamic Approaches. Int. Game Theory Rev. 2018, 20, 1750033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovay, J.; Ferrier, P.; Zhen, C. Estimated Costs for Fruit and Vegetable Producers to Comply with the Food Safety Modernization Act’s Produce Rule; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baikadamova, A.; Yevlampiyeva, Y.; Orynbekov, D.; Idyryshev, B.; Igenbayev, A.; Amirkhanov, S.; Shayakhmetova, M. The effectiveness of implementing the HACCP system to ensure the quality of food products in regions with ecological problems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1441479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, D.; Cavicchi, A.; Rocchi, B.; Stefani, G. Exploring costs and benefits of compliance with HACCP regulation in the European meat and dairy sectors. Food Econ. 2005, 2, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmke, M.D.; Bonanno, A.; Boys, K.; Smith, T.G. Food Fraud: Food fraud: Economic insights into the dark side of incentives. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2019, 63, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everstine, K. Economically Motivated Adulteration: Implications for Food Protection and Alternate Approaches to Detection. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, A.A. Phosphates for Seafood Processing. In Phosphates: Sources, Properties, and Applications; Nova Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 83–112. [Google Scholar]

- Spagnoli, P.; Defalchidu, L.; Vlerick, P.; Jacxsens, L. The relationship between food safety culture maturity and cost of quality: An empirical pilot study in the food industry. Foods 2024, 13, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhou, J.; Ye, J. Adoption of HACCP system in the Chinese food industry: A comparative analysis. Food Control 2008, 19, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J. Food Safety Monitoring and Surveillance in China: Past, Present, and Future. Food Control 2018, 90, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ma, F.; Rainey, J.J.; Liu, X.; Klena, J.; Liu, X.; Zhao, C. Capacity assessment of the health laboratory system in two resource-limited provinces in China. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai’an Municipal Bureau of Finance. 2024 Unit Budget Catalogue of Tai’an Food and Drug Inspection and Testing Research Institute (Tai’an Fiber Inspection Institute). 2024. Available online: https://czj.taian.gov.cn/module/download/downfile.jsp?classid=0&filename=13fc70c5a1384018bc3d1942992870ee.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- People’s Daily. National Market Regulation System Food Safety Sampling Non-Compliance Rate Was 2.74%. People’s Daily. 2025. Available online: https://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/pc/content/202511/26/content_30116951.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Xinhua News Agency. 2020 National Food Safety Sampling Monitoring: Overall Non-Compliance Rate 2.31. XinhuaNet. 2021. Available online: https://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2021-04/21/c_1127357953.htm (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Liu, Y.T. National Authority Released the Notice on Food Sampling Inspection in the Fourth Quarter of 2016. Health China. 2017. Available online: https://mtest.health-china.com/c/2017-02-06/646115.shtml (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Kunming Municipal People’s Procuratorate. Food Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China. 2022. Available online: https://www.kunmingjn.jcy.gov.cn/jwgk/jwzn/202203/t20220315_3581321.shtml (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Food Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China. National Laws and Regulations Database. Available online: https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail?fileId=&id=ff8081817ab22e0c017abd8d85a205f1 (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Beijing Political and Legal Affairs Network (BJ148). Bought Problematic Goods: Should the Compensation Be “Three Times” or “Ten Times”? 2021. Available online: https://www.bj148.org/fw/xzsc/wnzz/202103/t20210315_1601646.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Food Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China. National Laws and Regulations Database. 2021. Available online: https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail2.html?MmM5MDlmZGQ2NzhiZjE3OTAxNjc4YmY3NDVlMzA4ODQ%3D (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- The Beijing News. Meituan Waimai Responded to the Regulatory Interview, Saying It Will Seriously Fulfill Platform Responsibilities. 2019. Available online: https://m.bjnews.com.cn/detail/155246269214632.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Beijing Municipal Administration for Market Regulation. How to File a Consumer Complaint on the National 12315 Platform? Capital Window (Beijing Municipal Government Portal). 2025. Available online: https://www.beijing.gov.cn/fuwu/bmfw/bmdh/sh/rcxf/rcshbmjy/202504/t20250409_4060597.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Jingde County Market Supervision Administration. Interim Measures for Handling Complaints and Reports in Market Supervision Administration (Market Regulation Administration Order No. 20, 2019). Jingde County People’s Government Portal. 2024. Available online: https://www.ahjd.gov.cn/Jczwgk/show/2305595.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Chinese)

- Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, Z. Blockchain traceability adoption in agricultural supply chain coordination: An evolutionary game analysis. Agriculture 2023, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, A.M.; Shavell, S. Economic Theory of Public Enforcement of Law. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 45–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Li, T.; Liu, D.; Luo, Y. The impact of food safety regulatory information intervention on enterprises’ production violations in China: A randomized intervention experiment. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 7, 1245773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, Y. Blockchain Traceability Adoption in Low-Carbon Supply Chains: An Evolutionary Game Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.S.; Feng, Y. Consumer Risk Perception and Trusted Sources of Food Safety Information during COVID-19. Food Control 2021, 130, 108279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Describe |

|---|---|

| Number of consumer reports received by the government | |

| Transaction volume | |

| Average price consumers spend on prepared meal products | |

| When manufacturers violate regulations, consumers receive reporting rewards under the government’s active regulation | |

| The intensity of government regulation, where i = 1, 2 represent active and passive government regulation, respectively | |

| When the government is actively regulating, the fines paid by manufacturers to the government for violations | |

| When the government is actively regulating, manufacturers will provide compensation for consumers’ reports in violation of regulations | |

| The cost of government regulation. The higher the intensity of regulation, the higher the cost | |

| The extra cost of honest business operation by manufacturers | |

| Consumer reporting costs | |

| Losses suffered by consumers due to violations by manufacturers | |

| Losses suffered by manufacturers due to reduced revenue caused by consumers not reporting but not purchasing products | |

| Losses suffered by manufacturers due to false reports from consumers under passive government supervision | |

| The government provides compensation for consumers’ reports, which is proportional to the intensity of supervision | |

| Active government supervision brings increased credibility, which is proportional to the intensity of supervision | |

| The decline in total social welfare caused by manufacturers’ illegal operations | |

| The reputation of manufacturers is enhanced by their integrity operation | |

| The benefits that manufacturers’ integrity operation brings to the government |

| Consumer Reports | |||

| Government revenue | Manufacturer revenue | Consumer revenue | |

| Manufacturer integrity management | |||

| Manufacturers are operating illegally | |||

| Consumers Do Not Report | |||

| Manufacturer integrity management | |||

| Manufacturers are operating illegally | |||

| Consumer Reports | |||

| Government revenue | Manufacturer revenue | Consumer revenue | |

| Manufacturer integrity management | |||

| Manufacturers are operating illegally | |||

| Consumers Do Not Report | |||

| Manufacturer integrity management | |||

| Manufacturers are operating illegally | |||

| Equilibrium Point | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial State | Probability |

|---|---|

| Parameter | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 4 | 30 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.65 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.35 |

| Scenario | P (Active Reg.) = x | P (Report) = z | Gov Enforcement Cost | Gov Report-Reward Cost | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government-only active regulation | 0.838 | 0.250 | 0.309 | 0.015 | 0.325 | 0.038 | 0.362 | 89.6 | 10.4 |

| Consumer-only active reporting | 0.442 | 0.550 | 0.210 | 0.023 | 0.234 | 0.083 | 0.316 | 73.9 | 26.1 |

| Gov–consumer collaborative regulation | 0.650 | 0.550 | 0.262 | 0.029 | 0.291 | 0.083 | 0.374 | 77.9 | 22.1 |

| Policy Variables | Initial Value | Policy Changes (±10%) | Change in the Probability of Manufacturers Operating with Integrity Δy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government regulatory intensity | 0.7 | 0.77 | +11.2 |

| Manufacturer Integrity Cost | 0.2 | 0.22 | −9.8 |

| Consumer reporting costs | 0.15 | 0.135 | +7.6 |

| Government fines | 0.45 | 0.495 | +10.5 |

| Consumer compensation | 0.10 | 0.11 | +2.1 |

| Action | Lead Stakeholder | Operational Lever | Practical Implementation | Suggested KPI | Best-Fit Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk-based inspection targeting | Government | at lower cost | Prioritize high-risk products and repeat offenders using complaint + history + traceability signals | Non-compliance rate in targeted inspections; repeat-violation rate | All (esp. capacity-limited) |

| Calibrated penalty bundle | Government | Combine fines with credit downgrades, procurement restrictions, suspension for severe cases | Expected penalty proxy; recidivism reduction | High-capacity regulators | |

| “Complaint–verification–feedback” closed loop | Government + Platforms | Unified portal; case-status tracking; clear timelines; feedback transparency | Average handling time; valid-report ratio; satisfaction | Platform markets; capacity-limited | |

| Reporting friction reduction | Platforms + Government | Standard templates; auto-ID of merchant; evidence upload guide; one-click status query | Reporting completion rate; drop-off rate | All, especially low participation | |

| Reward alignment | Government | Moderate rewards for verified reports; avoid perverse incentives; publish rules | Verified report growth; false-report rate | Capacity-limited; early-stage rollout | |

| Traceability at CCPs | Firms + Government | (credibility), ↓ opportunism | Batch-level traceability; cold-chain temperature logs; CCP monitoring | Traceability completeness; CCP deviation rate | Cold-chain sensitive products |

| Compliance cost support for SMEs | Government + Leading firms | dispersion | Shared audits, shared labs, training, group standards, pooled traceability services | SME audit pass rate; coverage of shared services | SME-dominated regions |

| Internal incentive contracts | Firms | ↓ opportunism | Tie bonuses to quality KPIs; mandatory corrective actions | Complaint rate; corrective-action closure time | All firms |

| Data sharing and joint enforcement | Government departments | Interface inspection, health, agriculture, public security; joint task forces | Cross-dept case closure time; joint actions count | Complex jurisdictions | |

| Public transparency dashboard | Government + Platforms | ↑ trust, ↑ participation | Publish aggregated enforcement + complaint outcomes; anonymized case typologies | Trust survey proxy; participation rate | Platform markets; high public attention |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, J.; Cui, W.; Luo, L.; Xie, G. Collaborative Supervision for Sustainable Governance of the Prepared Food Industry in China: An Evolutionary Game and Markov Chain Approach. Sustainability 2026, 18, 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020615

Cao J, Cui W, Luo L, Xie G. Collaborative Supervision for Sustainable Governance of the Prepared Food Industry in China: An Evolutionary Game and Markov Chain Approach. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020615

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Jian, Wanlin Cui, Liping Luo, and Ganggang Xie. 2026. "Collaborative Supervision for Sustainable Governance of the Prepared Food Industry in China: An Evolutionary Game and Markov Chain Approach" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020615

APA StyleCao, J., Cui, W., Luo, L., & Xie, G. (2026). Collaborative Supervision for Sustainable Governance of the Prepared Food Industry in China: An Evolutionary Game and Markov Chain Approach. Sustainability, 18(2), 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020615